Linda F. Garner, PhD, RN

Karen A. Bufton, MS, RN, C

Throughout the 20th century, development of Baylor University Medical Center (BUMC) as the humanitarian hospital envisioned by Dr. George W. Truett and other Dallas-area sponsors was as dependent upon the devotion and efforts of nurses as upon the dedication and skills of physicians. Nurses have contributed to the quality of service—both general nursing care and highly specialized technology-based nursing care—that has established the standing of BUMC and other Baylor Health Care System (BHCS) institutions among the finest US health care institutions.

Individuals committed to humanitarian and professional service have built the nursing care at BUMC and BHCS and the education programs at Baylor University School of Nursing (BUSN). In 1912, Helen T. Holliday brought a team of nurses and the nursing standards of Johns Hopkins Hospital to the recently established Texas Baptist Memorial Sanitarium (TBMS), progenitor of BUMC. Since that time, over a period of nearly a century, nurses who were trained or served in BUMC hospitals have cared for patients with skill and dedication.

Among Baylor nurses, Hattie Brantley began a distinguished career at Baylor University Hospital (BUH). She was a student nurse during the now nearly forgotten years when student nurses provided most nursing service at BUH. After graduating in 1937, she continued to work at BUH until she was accepted for service in the US Army in 1939 (1). She was stationed at Fort Sam Houston before being transferred to the Philippines along with Earlyn Marie “Blackie” Black, a 1938 graduate, to become part of the first unit of US women ever sent into battle. When Manila fell, the nurses were sent to Bataan, where they helped build hospitals and care for the sick and wounded. With the fall of Bataan imminent, the nurses, including Lts. Brantley and Black, were moved to Corregidor in April 1942. Although some army and navy nurses were evacuated to Australia, most remained and continued to care for the wounded in Malinta Tunnel, where they had set up a hospital to avoid bombing. When the US forces surrendered to the Japanese, 54 nurses, including Lts. Brantley and Black, were moved to the main internment camp at Santo Tomas University (2) (Figure 1). Lt. Brantley was able to take some university courses, although she and the other nurses were kept busy caring for patients for as long as they were prisoners of war. Conditions were severe because of lack of supplies, and the nurses survived on starvation rations for several months prior to liberation. Two other Baylor nurses were among those eventually flown in to relieve the liberated nurses who were prisoners of war (3). In spite of all the hardships, Ms. Brantley continued her career as an army nurse after World War II, retiring as a lieutenant colonel.

Figure 1.

Lieutenant Hattie Brantley (left) and Lieutenant Earlyn Marie “Blackie” Black (right) with Brigadier General Hart in 1945 at a tea given in their honor by the recruitment committee of the Dallas County Chapter of the American Red Cross. Both nurses were among the prisoners freed from the Santo Tomas prison in Manila.

Baylor nurses have distinguished themselves nationally and internationally as civilian nurses as well as in military service. Margo McCaffery, a nurse who spent her student years at Baylor, graduating in 1959, has become an internationally recognized author and speaker and an authority on pain management. Barbara Montgomery Dossey, a 1965 graduate of BUSN who served for 2 years in BUMC’s cardiac intensive care unit (ICU), is now internationally recognized as a pioneer in the holistic nursing movement and as the author of a biography of Florence Nightingale. May Gloeckner Wilkinson graduated from Baylor Hospital School of Nursing in 1927, became a staff nurse, was promoted to director of nursing services on June 1, 1951, and served in that position until she became a nursing consultant in 1964, retiring in 1974.

Baylor nurses have contributed to the development and modernization of nursing internationally as well as in Dallas. William Denton, Rene Bailey, and BUSN’s Dr. Linda Garner, along with other BUMC nurses, helped rehabilitate and modernize nursing in Romania toward the end of the 20th century. Shirley Shofner provided consulting assistance for development of nursing services and administration at the American-British Cowdray (ABC) Hospital in Mexico City. Nurses from ABC and other hospitals abroad came to BUMC for short periods of time in the 1980s and 1990s to observe and learn contemporary, technology-reliant nursing methods.

Many Baylor nurses have become nursing executives and have taken on even broader responsibilities at BUMC and elsewhere in BHCS and other health care systems. The cadre of professional nurses serving as health care system executives in 2000 included JaNeene Jones, vice president of BUMC; Remy Tolentino, vice president and chief nursing officer of BUMC; Linda Plank, vice president and administrator of BUMC’s surgical service; Shirley Shofner, vice president of BHCS and executive director of the HealthTexas Provider Network; Geraldine Bruckner, president of Baylor Specialty Hospital; and others.

Nursing services and education developed within BHCS, BUMC, and BUSN by drawing on traditions and resources of nursing in the USA and internationally. In turn, during the 20th century, Baylor nurses contributed to development of the profession as well as to development of the Baylor institutions.

EARLY DEVELOPMENT OF NURSING

Nursing is an ancient but still constantly evolving profession. The profession has had to keep pace with changing needs of individuals and families, developments in medical care, social changes—including changes in the status of women in society— and economic conditions. While the profession’s roots are deep, the adaptability of nurses as professionals has sustained and progressively increased their responsibilities in health care. Today the nurse—whether a woman or a man—must be a professional and may also be a technical expert, administrator, or executive. And perhaps more importantly, the nurse of today must be able to adapt to change quickly as technology and health care evolve.

There are numerous accounts of nurses and the varied functions they performed even before the Christian era. Since the beginning of the Christian era, nursing has developed progressively but unevenly as societies and institutions have changed. Religious brothers and sisters were particularly active in providing nursing care in centuries prior to the Reformation. While nursing declined and changed adversely during the Reformation, afterwards nursing services were redeveloped out of necessity and a sense of Christian charity.

Pre-Reformation charitable institutions were sponsored by church-related “religious confraternities.” Such institutions flourished in the cities of what is now Italy: Florence, Genoa, Rome, Venice, and others. In the 1620s, a revitalized Catholic Church set about reforming charitable institutions in France. The Company of the Holy Sacrament established the first institution, the Hôpital General, in 1656, in Paris under Cardinal Mazarin. By 1700, >100 hôpitaux generaux had been built throughout France, where nurses provided care with increasing training and skill. Catholic reforms also led to the formation of nursing communities, usually of women. These included the Daughters of Charity (Filles de la Charité) founded in 1633 by Vincent de Paul and Louise de Marillac. The sisters supplied practical nursing skills and labor in foreign as well as French hospitals (4). Their skills and efforts were essential to the functioning of French hospitals and were responsible for significant improvements in the care of the sick in French colonies. The French sisters were also an important influence on Florence Nightingale and other Protestant nursing reformers (5).

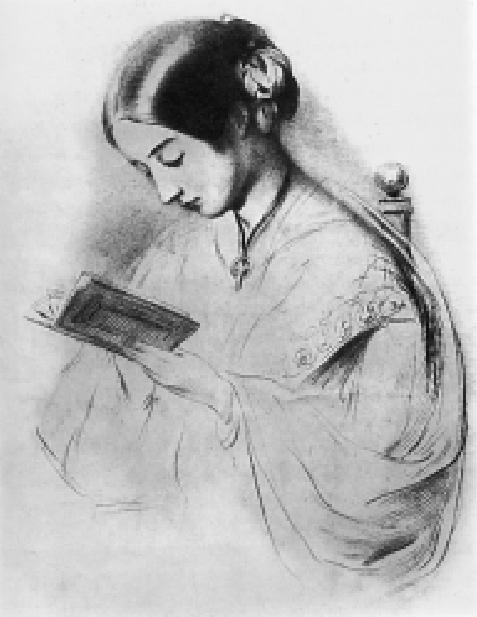

The first and quite brief formal training for nurses was offered by a Protestant pastor, Theodore Fliedner, in the 1830s at the Deaconess Institute in Kaiserswerth, Germany. This paved the way for development of modern training of nurses and modern practice of nursing. In 1853, after a few weeks’ study at the institute and a longer visit with the Daughters of Charity in Paris, Florence Nightingale (Figure 2) was appointed superintendent of London’s Establishment for Gentlewomen During Illness. She soon became superintendent of nurses at King’s College Hospital.

Figure 2.

Florence Nightingale. Photo: Corbis.

The outbreak of the Crimean War in March 1854 was Miss Nightingale’s opportunity to provide leadership and inspiration for the development of nursing as a profession comprising trained and dedicated individuals prepared to take responsibility and initiative as qualified professionals. On November 4, 1854, Miss Nightingale and a party of 38 nurses—10 Roman Catholic sisters, 8 Anglican sisters, 6 St. John’s House nurses, and 14 nurses from various hospitals—began development of professional nursing services for the British Army during the Crimean War. Within 6 months, in spite of military resistance, Miss Nightingale had transformed the hospital at Scutari, across the Bosphorus from Istanbul, reducing the death rate from >40% to 2%. On her return to Britain in August 1856, she was proclaimed a national hero. She greatly influenced the development of nursing education and practice worldwide and in the USA (6).

Florence Nightingale was a skilled organizer, and she insisted that nursing recruits receive thorough training in nursing theory and practice. Her system of training, which emphasized service, promoted nursing as an honorable profession for women. Recruits came from all social classes; the well-to-do studied for 2 years as paying students, while promising young women from humbler origins trained for 1 year. Nurses trained in the Nightingale system carried it throughout the British Empire and beyond, setting up similar training programs in British colonies and in Sweden, the USA, and Denmark in the last third of the 19th century. As an outgrowth of the Crimean War, nursing became a skilled profession embodying the esprit de corps Miss Nightingale so valued (7).

DEVELOPMENT OF NURSING IN THE USA

In colonial North America and the USA until the middle of the 19th century, health care—medical care and nursing care— was home centered. The poor and destitute were cared for in almshouses or hospitals with few characteristics of modern hospitals. Nursing care in institutions was primitive, provided by recovering or former patients and menial workers with little or no training or supervision. As more modern hospitals were developed in urban centers, often with denominational sponsorship, nursing care gradually improved; it did not become professional, however, until well into the second half of the 19th century.

Nursing care prior to the Civil War was greatly influenced by cultural attitudes and social norms that differed regionally. In the South, including Texas, during the 19th and into the early 20th century, nursing was carried out by women for members of their immediate families only. Nursing of strangers was considered a task for men, including slaves; later, disenfranchised black women also nursed strangers. During yellow fever epidemics, for example, only men were considered to have the courage and stamina for nursing, although poor whites and blacks were allowed to carry out the more routine and demeaning tasks involved in caring for sick patients. By World War I, the South had finally developed the social, economic, and political capital needed to construct hospitals. That war, in fact, marked the first time that the actual care of the sick, rather than just organizing others to do the work, became acceptable work for the elite white women of the South. They viewed nursing as their patriotic contribution to the war effort, and soon white women of other classes followed suit. These events in the South reflect the significant change that occurred in many regions as women took over the more heroic aspects of nursing from men (8).

Much as the Crimean War brought about reform and advances in nursing, the US Civil War demonstrated the importance of nursing and led to the development of professional nursing in the USA in the later decades of the 19th century. Good nursing was considered as important as good medical care in the Confederate hospitals, and the patients preferred women nurses. The military hospitals offered full-time employment for women nurses at a time when such opportunities were rare for women and carried a social stigma. These self-sacrificing lay women not only contributed to the rise of trained nursing as a profession but were good morale builders for the wounded soldiers. Their positive effects on the wounded demonstrated that the hospital staff were as rightfully concerned with the mental as with the physical well-being of their patients (9).

Confederate Army regulations required 1 nurse for every 10 patients, but nurses of any sex or race were difficult to come by. The only trained women nurses at the start of the war were Roman Catholic sisters from various orders, notably the Sisters of Charity. The Sisters of Charity were in demand as nurses, but there were <200 of them. Nurses were also recruited from the ranks of soldiers. Most had no nursing experience; some remained unskilled and were relieved from nursing duty, while others became quite skilled. Many military hospitals continued the antebellum tradition of recruiting convalescents to serve as nurses until they were ready to return to active duty (10).

In the North, many female nurses served in general hospitals or well to the rear in military actions. The number who functioned in field hospitals was never large. Some regiments were accompanied by a woman often known as a matron, who served as washerwoman and would assist in caring for the wounded, but generally the nurses in the field hospitals were men. A few women were allowed to work at specialized tasks, such as supervising the diet of the wounded, that included nursing duties. Women freelance nurses and “reliefers” worked at the front during and after major campaigns, and some of these became well known. “Mother” Bickerdyke, for example, was a competent nurse who eventually became, at General Sherman’s invitation, the only woman nurse at the military hospital at Chattanooga. After the carnage of Gettysburg, numerous northern women served in field hospitals, and even southern women were allowed to come to the site to nurse the Confederate wounded. The most famous of these volunteer women nurses was Clara Barton. These women came of their own free will, received no pay or compensation of any kind, and had no official connection with the military (11).

The contribution of women nurses to morale within hospitals was great. One medical historian commented, “Their presence in hospitals was not only one of the outstanding novelties of the war, but an event in American social history. The war opened the gates of a great profession to women at a time when their economic opportunities were scarce” (12).

The development of the modern hospital became possible as nursing was professionalized and antiseptic surgery became feasible and gained acceptance. This new interest in hygiene came not from doctors but from upper-class women. In 1872 New York, for example, the State Charities Aid Association, a women’s group, began to monitor the conduct of public hospitals. They discovered very poor conditions in some of the hospitals and pushed for the formation of nurse training schools to help improve the standard of patient care. The doctors were divided as to the wisdom of this proposal but eventually came to accept and depend on the trained nurses who came to work in the hospitals(13).

Well after the close of the Civil War, Dr. Marie Zakrzewska established the first general training school for nurses in the USA; it began at the New England Hospital for Women and Children after the hospital was completed in 1872. The course followed many of the guidelines established by Florence Nightingale but was only 1 year in length and focused primarily on clinical practice (14). The first Nightingale schools were established the following year at Bellevue Hospital in New York, Massachusetts General Hospital, and New Haven Hospital. These schools were sponsored by civic and philanthropic groups and were operated separately from the hospitals. The students were often sent out on private duty and visiting nursing assignments in addition to their hospital duties (15).

After the founding of the first Nightingale schools in 1873, other hospitals began to open their own schools. There were 15 nursing schools in the USA in 1890. By 1900, 432 schools of nursing had been established. Initially these schools were to help create a “home” atmosphere among the nurses by teaching similar habits and ideas of hospital traditions and service. Schools of nursing soon came to be considered a necessity for hospitals as the most economical means of providing care to patients. Most schools were essentially apprentice systems, with students working long hours caring for patients. Discipline was strict. Physicians taught nursing theory, and the superintendent and her assistants supervised patient care. Care consisted of providing proper nutrition and hygiene and carrying out treatments ordered by the physician (16).

After finishing their training, nurses found few paid positions in hospitals. Most became private-duty nurses, working with little or no supervision. Practical nurses who had limited training practiced along with the trained nurses (17). Although standards for nursing had not yet been established, Johns Hopkins Hospital School of Nursing, under the leadership of Isabel Hampton Robb, appointed nurses who were known for their teaching of bedside nursing to instruct the students (18).

While many have lamented the lot of nurses in the USA during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, others are now reevaluating nursing history more objectively. They believe that many women chose nursing not for the economic rewards—indeed, the compensation was poor and was delayed until the training was completed. Rather they chose nursing because the independence and leadership opportunities it offered were not surpassed or even equaled by any other work open to women. Nursing offered a skilled profession that combined meaningful work with the feminine “ideal” of service and caring, a calling that offered self-respect and self-support with social esteem. It also offered them the opportunity to pursue more traditional feminine roles of wife and mother, with the option of returning to the workforce at any time. As D’Antonio put it, “The nursing diploma meant even more: it also meant the possibility of constructing lives with meaningful, easily accomplished, and socially sanctioned connections between personal responsibilities and professional commitments, and between private interests and public concerns” (8).

In short, D’Antonio continued, nursing offered women a way to challenge the prevailing social norms about women’s roles. It also offered them a way to transform health care in the USA. These nurses wielded a great deal of power (8).

NURSING AT THE BAPTIST MEMORIAL SANITARIUM: 1903–1920

When TBMS was opened in the former Good Samaritan Hospital building in 1904, Mildred Bridges was appointed superintendent of nurses. One of her first duties was to open a training school for nurses. All students were, in keeping with the times, young ladies from “good” families. This school was closed in 1905 when the hospital itself was closed to await construction of a new building.

Miss Bridges was a graduate of the Missouri Baptist Hospital School of Nursing in St. Louis. After the closing of TBMS, she held positions in various hospitals in north central Texas. She was a leader in the profession of nursing in the state and was instrumental in the organization of the Graduate Nurses’ Association of Texas. She served on the legislative committee that drafted the first nurse practice act passed by the Texas legislature in 1909 (19).

At the time of the opening of the new TBMS in 1909, its board of trustees adopted comprehensive bylaws that defined the responsibilities of the superintendent of nurses and the principal of the training school. The bylaws provided for the following:

The oversight of the head nurses, assistant nurses, probationers, and orderlies is committed to the superintendent of nurses.

She is charged with the responsibility of the nurses’ home and the instruction of nurses in the training school and is authorized to prescribe courses of study, to select and accept probationers, to keep their accounts, and to make contracts with them for their respective terms of service. She is empowered to make, with the approval of the superintendent of the sanitarium, all necessary rules for the governance of nurses.

She shall constantly supervise all nursing work and shall observe carefully the manner in which nurses and orderlies care for the sick.

It shall be her duty to make requisition for ward supplies. She shall see that proper economy is exercised in the distribution of the food, in the use of all materials for surgical operations and dressings, and in all ward supplies and furnishings.

She shall have charge of the surgical storeroom and give due notice to the superintendent when further supplies are required.

When the new TBMS building opened on October 14, 1909, nurses were again needed to care for patients. The new superintendent of nurses, May Marr, established a training school for nurses with 9 students (Figure 3). The school opened as the Training School of the Texas Baptist Memorial Sanitarium and continued as such until 1921, when the training school was listed in the charter as one of the professional schools of Baylor University (BU) (Figure 4) (20). Seven different people, including one physician, held the position of superintendent of nurses during the first 3 years of the hospital. The superintendent of nurses and physicians at the hospital taught the nursing classes. Rules were strict; the work, menial and hard. Pupil nurses were required to scrub the walls as well as provide nursing care on 12-hour shifts (21). The first nursing graduation exercises were held at the Gaston Avenue Baptist Church with Dr. Samuel P. Brooks, president of BU, presenting the diplomas (22). Ola Chumley was the first graduate, finishing early in November 1911, as she had been in training at St. Paul Sanitarium before coming to TBMS (22). Nursing responsibilities were defined in the rules of the nurses’ training school published in 1912. The head nurse was responsible for the condition of the floor and for the work and conduct of the nurses in her charge. She was to see that patients received proper care and that nurses were relieved for sleep and recreation. Each head nurse received a half day off each week and could not be gone at the same time as another head nurse.

Figure 3.

May Marr, superintendent of nurses when the new Texas Baptist Memorial Sanitarium opened in 1909.

Figure 4.

Students admitted in 1910 to the Nursing Training School of the Texas Baptist Memorial Sanitarium. Left to right: bottom row—Mellie Mallord, Ola Hobson, May Pearl Moore; middle row—Anna Galon, Stella Leach, Belle Nichols, Eva Hembee, Esther Lynch; top row—Nathalee Phelps, Mary Watkins, Arvell Grubbs, Dessie Stanfield.

A senior student was left in charge when the head nurse was gone and could call a head nurse from another floor in case of emergency. Graduate nurses employed by the hospital were required to abide by the same rules as students. The superintendent of nurses was responsible for students and graduate nurses alike. She could dismiss any student during the probationary period without stating a reason. After the probationary period, dismissals had to be discussed with a committee of the board of directors. Hours of duty were from 7 am to 7 pm and from 7 pm to 7 am. Day nurses were expected to be in their rooms with lights out by 10 pm; night nurses had to be in their rooms from 8:30 am to 4 pm. They were also on call for emergencies at any hour, night or day. They were not allowed on duty without the full uniform and were not to leave the hospital grounds dressed in their uniforms. The hour for rising in the morning, as well as requirements for chapel attendance, social relations, and other activities, were specified by the rules (23).

These rules established by TBMS for its nursing school were quite in keeping with practices of contemporary eastern hospitals. Most maintained residences for nursing students and nurses that were located in buildings on or near the hospital campus but separate from the hospital facility itself. Hospital nurses of that era were subjected to severe discipline. Their rooms could be inspected at any time, and they were reprimanded, even expelled, for any infraction of the rules, including impertinence, carelessness, overfamiliarity with patients, or talking with a houseofficer. They were not allowed to wear jewelry or elaborate hairstyles, and the type of shoes that they might wear was dictated. At most hospitals, nurses were not allowed to leave the grounds without a pass. This control was seen as necessary for both practical and moral reasons. As Rosenberg notes, “Although some administrators questioned the hours and arduousness of nurse training, few challenged the structural subordination within which that work was performed” (24).

A practical consideration supporting the discipline imposed by TBMS and other hospitals and their schools of nursing was that the families—especially the fathers—of the women would not have allowed them to become nurses if they were not in protected environments.

Stability came to TBMS nursing in 1912 with the arrival of Helen Holliday. Miss Holliday was a graduate of Johns Hopkins University Hospital Training School and attended the Teachers College of Columbia University. She served as head nurse and supervisor at Johns Hopkins Hospital and Allegheny General Hospital before coming to TBMS (25). A few other graduates of Johns Hopkins also came to assist her (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Nurses at the Texas Baptist Memorial Sanitarium in 1916. Standing, left to right: Christine L. Smith, RN, operating room supervisor; Miss Howland, dietitian; Mr. Franklin, superintendent of TBMS; Katherine Duvall, RN. Seated, left to right: Judith Wiley, RN; Emma Wood, RN; Helen Holliday, RN.

At that time, the new Texas Board of Nurse Examiners required that all nursing schools have at least 2 paid instructors, of whom one was the superintendent of nurses. New appointments were an assistant to the superintendent of nurses, a graduate assistant to the head nurse in the operating room, and an instructor in dietetics (26). The new graduate nurses took state board examinations for the first time in 1913.

At TBMS, by 1913 the number of surgeries had increased so that one person could not supervise all of them. A diet kitchen for the preparation of special diets had been added; the children’s ward was fully equipped; and the clinic increased to serve 60 to 70 patients a day. The nursing staff consisted of 8 graduate nurses and 63 students. By 1915, the number of students had increased to 80. This enabled the hospital to provide pupil nurses for special duty. It also allowed more time for classes and gave the students more time for study and recreation. An instructor of nurses was added to devote her entire time to the theoretical work of the pupils. This gave the heads of departments more time for other duties. The number of students continued to increase.

A new nurses’ home that would accommodate 200 nurses opened in 1918 (27). The new home, like those at other hospitals across the nation, was in a building separate from the hospital.

World War I had an impact on the environment in which nursing functioned at TBMS, affecting both nursing education and nursing care. Nurses were needed by the military as well as by the growing hospital. A unit of doctors, nurses, and hospital men known as the Baylor Medical and Surgical Unit served in Europe. In response to a call to increase the number of nurses, 50 students were admitted in 1919. Over 100 of the nurses developed influenza, and as many as 60 were off duty at one time; however, those who were left on duty made no complaints. The shortage of nursing graduates available for teaching, public health, and executive positions as well as a shortage of students for patient care affected TBMS as well as the rest of the nation (28).

The following year the hospital was crowded, with an average of 225 patients. The nursing staff was composed of 12 graduates and 100 students.

Although California had passed the first 8-hour-per-day work law in 1911, expanding it to include student nurses the following year, students at TBMS still worked longer hours. A policy of 12 hours of duty instead of 24 hours for special-duty assignments was instituted (29).

NURSING AT BAYLOR HOSPITAL AND BAYLOR UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL: 1920–1950

In 1921, TBMS became Baylor Hospital (BH), and the hospital’s school of nursing became a parallel legal component of BU following consolidation of the TBMS and the scientific schools—Baylor University College of Medicine (BUCM), Baylor College of Dentistry, Baylor School of Pharmacy, and Baylor Hospital School of Nursing (BHSN)—under the president and board of trustees of BU. The name of the nursing school was changed in 1936 to Baylor University School of Nursing (BUSN).

The BH superintendent of nurses was given the title of dean of BHSN; she was the administrative head of the school and was responsible for directing the nursing service of the hospital. At the time, there were 4 faculty members in addition to Miss Holliday plus 20 head nurses and supervisors and a total of 125 students. The hospital had 250 beds with an average daily census of 226. The beds were allocated as follows: 30 to men’s medical, 30 to women’s medical, 6 to children’s medical, 60 to men’s surgical, 60 to women’s surgical, 6 to children’s surgical, and 28 to maternity patients. A total of 9077 cases (2220 medical and 6857 surgical) were treated that year (30). A new building for women and children was completed in 1922 and named the Florence Nightingale Hospital. This allowed expansion of pediatrics, obstetrics, and gynecology services. Another building provided space for clinics, lectures, laboratories, and other services (31).

The Goldmark Report, published in 1923, resulted from a study of nursing across the country and recommended educational preparation for nurses and accreditation of nursing schools. The nursing school at BH became one of two schools in the southwest to receive a class A rating by meeting all requirements of the New York Board of Nurse Examiners (32).

The new governing board of the Baylor-in-Dallas institutions, the Dallas executive committee of the BU board of trustees, continued through its house committee to oversee day-to-day operations of the hospital and the nursing school. The house committee concerned itself at various times even with the admission and actions of individual nursing students. As in prior decades, not only the professional performance but the personal activities of individual nurses, physicians, medical students, and housestaff were subject to board and administrative scrutiny and discipline. Threats of public embarrassment and even dismissal from the hospital were used to ensure compliance with the rules of behavior (33). Taking such action was quite in keeping at that time with the responsibilities of directors of a hospital and nursing school. Boards were expected to act in loco parentis to protect the interests of nursing students, nurses, patients, and the community.

Relationships between nurses and medical students were carefully monitored by the administration and house committee of the board of trustees. Even so, the prospect of meeting young doctors was one of the attractions of enrolling in nursing school for young ladies, if not their fathers. The prohibitions on married nursing students continued.

As early as the 1920s, the responsibilities of hospital nurses broadened as technology advanced. The increasingly professionalized nurse was making more decisions about patient care, documenting decisions on charts. Nurses took temperatures and began measuring blood pressure and keeping track of the fluid intake and output of patients with metabolic diseases.

During the 1920s, both BH and BHSN progressed and worked in unison under the Baylor-in-Dallas concept. Economic conditions—both national and those peculiar to the Dallas area—were alternately favorable and adverse. During the entire decade both institutions, while continuing to progress in terms of service numbers and quality, were chronically underfinanced. Both, especially the hospital, were called upon to provide financial support to BUCM, since it received no financial support from BU or the Baptist General Convention of Texas (BGCT) and on its own could not marshal the financial resources needed to maintain accreditation. In spite of their efforts to support BUCM, both the hospital and nursing school were criticized by the medical staff of the hospital, which was in large part also the faculty of the medical school.

Helen Holliday resigned her position in 1923 upon her marriage to Dr. John R. Lehmann. Lucile Burlew, a 1917 graduate of the TBMS training school for nurses, became the new superintendent of nurses. Facilities and services continued to be expanded. Nursing services and training apparently continued uneventfully. However, physician dissatisfaction and a new administrative structure to implement the Baylor-in-Dallas concept brought a change in nursing administration.

In late 1928, a committee of the medical school faculty prepared a report critical of both nursing in the hospital and the work of the nursing school. The Dallas executive committee of the BU board of trustees considered several of the complaints valid, among them the nurses’ lack of respect for the dean of the medical school, lack of proper appreciation of duties to the patient, and lack of discipline and professional dignity. The executive committee also addressed a complaint from the physicians implying that hospital nurses encouraged patients to hire private nurses and then proceeded to neglect the patient when the private nurse was in place. The faculty report stated that an average of 33 to 35 private nurses were working in the hospital at any given time (34).

The medical school faculty committee report also addressed the issue of the number of nurses being trained. The report concluded that too many trainees were being accepted and that the number should be reduced to no more than 125 total student nurses over all training levels. The faculty considered that this would be an appropriate number for the average patient census of 250 to 300 patients (34).

In 1929, the faculty members, including Dr. Edward H. Cary, dean emeritus of BUCM and chairman of the advisory board, after more detailed study, made comprehensive recommendations to the Dallas executive committee of the BU board of trustees that called for departmentalization of the medical staff of BH and the faculty of BUCM. They argued that “departmentalization as contemplated will make it possible to have fewer nurses—undergraduate, special and supervising” and that a “reduction of 25 in the enrollment of the training school would mean a savings of $30,000 or more per year. Only having the number of nurses actually needed will prevent the creation of a situation of divided responsibility, opportunity for undue idleness, waste and loss of efficiency… . The amount saved in this manner can well be usedto increase the efficiency of departments and other phases of the hospital.” Faculty members also noted that reducing the number of nurses in this manner might make it possible to increase income by renting rooms in the nurses’ home to “convalescent patients, relatives and friends of patients at a reasonable rate.”

While it is somewhat unusual for a medical staff or medical school faculty to recommend reducing nursing staff, it is possible that Dr. Cary and his colleagues foresaw the possibility of reallocating hospital income to benefit the always-underfinanced medical school.

Nationally, efforts during this era were continuing to improve nursing education and nursing service in hospitals; the approaches taken were broader than those of the BH medical staff and BUCM faculty. A Committee on Grading of Nursing Schools was established through the joint efforts of the American Medical Association and professional nursing associations. After a national survey of nursing education, the committee cited problems that included poorly prepared students; a poor educational environment in nursing schools, especially the smaller ones; reliance on apprenticeship training rather than education; inadequate financing of nurse training; and reliance on students rather than graduate nurses to provide hospital nursing services (35).

The Grading Committee urged action to improve nursing education and service. Reform, it was decided, should have the following 4 basic goals:

To reduce and improve the supply. To make a decisive and immediate reduction in the number of students … and to raise entrance requirements high enough that only properly qualified women would be admitted to the profession.

To replace students with graduates. To put the major part of hospital bedside nursing in the hands of the graduate nurses and take it out of the hands of student nurses.

To help hospitals meet costs of graduate services.

To get public support for nursing education (36).

The 1928 report of the Grading Committee played a role in some ways similar to that which Flexner’s report of 1910 played in the education of physicians.

To alleviate existing problems and to placate the medical staff and faculty, in 1929 the Dallas executive committee of the BU board of trustees asked Helen (Holliday) Lehmann to resume the position of superintendent of nurses (37) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Helen Holliday Lehmann, RN, superintendent of nurses from 1912 to 1923 and 1929 to 1943.

Lack of financial resources continued to limit the ability of BH to change the composition of the institution’s nursing staff as recommended by the Grading Committee. Registered nurses (RNs), while available in the community, could not be employed in the numbers required to meet patient care needs and physician expectations; the reliance on nursing students had to continue. At BH—as elsewhere in Texas and nationally—the Grading Committee’s proposal to replace students with graduates could not be implemented until improved means of financing health care could be developed.

BH led the nation in taking an innovative approach in 1929 when, in cooperation with the Dallas Independent School District, a teachers’ “sick benefit plan” was established. The plan was so popular and successful that it began a national movement to provide private prepaid financing for hospital care. The Baylor Plan allowed teachers (and subsequently employees of other organizations) to make modest monthly payments in exchange for care at BH for a specified number of days. The success of the plan in Dallas—benefiting both teachers and BH—led to adoption of similar plans by other hospitals in Dallas and across the nation. The national Blue Cross Plan, established under the aegis of the American Hospital Association, was a direct outgrowth of the Baylor Plan. The Blue Shield Plan was developed later under American Medical Association sponsorship for prepayment of physicians’ fees.

These plans continued to grow, and over the next several years more individuals and their dependents were covered by hospitalization insurance. This gave hospitals, including BH, increasing financial resources that allowed employment of more RNs. It wasn’t until after World War II, though, that they were able to significantly reduce reliance on the use of student nurses.

In the 1930s, the Dallas executive committee of the BU board ceased to appoint a house committee to oversee operations of the Dallas units. From that time, the hospital and nursing school relied increasingly on the hospital administrator and superintendent of nurses to oversee day-to-day activities.

The depression years were a period of hard times for nurses as well as others in the nation. The number of schools decreased because hospitals were suffering from financial constraints. Jobs for nurses dwindled since most were private-duty nurses caring for patients in their own homes. Many returned to hospitals where they had trained, offering to trade their services for room and board (38). Conditions at BH were equally difficult. No money was available to upgrade facilities or curriculum for students. Graduate nurses included only Mrs. Lehmann, 1 assistant, and 2 others; together they were responsible for teaching and nursing administration of the hospital. There was 1 graduate nurse for each floor, which consisted of several patient units composed of at least 60 patients. Contrary to standards of the time, students were assigned as head nurses (39). Compliance with the regulations of the Texas Board of Nurse Examiners, which called for 1 graduate nurse for each 25-bed unit, would have required 11 graduate nurses, 7 more than the 4 BH was financially able to provide (40). By 1934, the number of graduate nurses had increased to 30 head nurses and 20 general-duty nurses. Increasing numbers of patients were also admitted. Admitting students twice a year and improved curriculum and facilities increased both the quality and amount of care received by patients (41).

While a nursing school committee continued to oversee the school in the 1930s, it was replaced by a nursing school council in 1940 following a visit by representatives of the accrediting committee of the National League of Nursing Education. The council comprised the dean of the nursing school, dean of BUCM (until BUCM moved to Houston in 1943), administrator of BUH, chairmen of various medical school departments, a nursing school alumnae representative, and a “prominent laywoman of Dallas” as regular members. Ex officio members were the chairman of the Dallas executive committee of the board, the assistant dean of BUSN, and the educational director of the nursing school. The board delegated to the council the following responsibilities:

To study the educational, professional, and financial needs of the school.

To cooperate with the faculty in its responsibilities and to consider and pass upon recommendations made by the faculty.

To nominate to the board of trustees the administrative and faculty personnel of the school.

To assist in securing funds for the school.

To assist in interpreting the aims of the school… .

To assist in the preparation of a budget for the school.

To prepare for the board of trustees reports… .

Except for emergency and/or minor matters, the recommendations of the nursing council shall be referred to the board of trustees through the advisory council (42).

World War II again focused attention on the needs for nursing and nursing education across the country. Hospital admissions increased while, at the same time, large numbers of qualified nurses were needed in military service (43).

The Bolton Nurse Training Act of 1943 authorized the creation of the Cadet Nurse Corps (Figure 7). This program was designed to recruit more nursing students annually and to accelerate the curriculum. The newly developed Division of Nursing Education of the US Public Health Service visited the participating schools and hospitals to verify that standards were being met (44).

Figure 7.

The first group of the 1945 class to begin the senior cadet period. Left to right: Doris Helton, O. Bonnie Schroeder, Ena Kingsbury, Jane Tate, Gloria McElroy, Mary Kay Roberts, Lorena Templeton.

Enrollment of nursing students increased at BUSN. Staffing did not improve, however. As in World War I, a Baylor unit including 8 BUH nurses left for service in the army. A group of married nurses returned to active nursing at BUH to help meet the shortage. A postgraduate program was begun to enable nurses to correct deficiencies in their basic courses and to qualify for military service. Certificates were presented in general nursing and obstetrics (45).

The Baylor unit was designated the 56th Evacuation Hospital. It was activated in March 1942, trained for a year in the USA, and served in North Africa and Italy. The unit’s mission was to serve as a 750-bed tent hospital in close support of the armed forces and for evacuating patients to larger base hospitals when necessary. The unit was made up of 37 medical officers, 4 dental officers, 47 Army Nurse Corps officers, 4 administrative officers, 1 quartermaster officer, and 2 chaplains. Of the officers, 47 were women and 47 were men. Most of the medical officers were members of the BUH medical staff. Nurse officers included BUH nurses as well as nurses from elsewhere, BUH having too few RNs on its staff at that time to fill the complement.

The Baylor unit served with distinction in North Africa and Italy, as described more fully in Dr. Ben Merrick’s history (46). The most arduous period of its service was at Anzio in February1944. The 56th admitted >1100 battle casualties in the first 36 hours. On the night of February 12, members of the 56th saw the heaviest raid on Port Anzio, with several bombs landing in the unit, fatally wounding army nurse Second Lt. Ellen Ainsworth, the first person in the Baylor unit to die. A proposal to move all nurses from the beachhead was discussed but was rejected by the nurses. The operating room nurse remembers that “at one point our commanding officer got the nurses together and asked whether we wanted to be evacuated. It was pretty bad, but we decided if the infantry was going to stay, we were going to stay.”

On February 10, 1944, the battle was extremely intense. As Lt. Mary Lou Roberts supervised several operations that were under way, German shrapnel started ripping through their surgical tent. She said, “We had patients on the table and we wanted to at least get them off. I said something like, “Maybe we can keep going before this gets too bad.’ It went on for 30 minutes or so. We just kept working.” Her superiors were so impressed with her coolness and inspirational personal conduct they recommended her for the Silver Star.

On February 21, 1944, Major General John Lucas, Anzio beachhead commander, presented the Silver Star to 3 nurses, beginning with Lt. Mary Lou Roberts, the first woman so decorated in the history of the US Army. Her valor also earned her a chapter in Mr. Tom Brokaw’s book, The Greatest Generation, published 54 years later (47).

On August 4, 1945, the 56th Evacuation Hospital admitted its last patient. In 25 months on foreign soil, the hospital had admitted and cared for 73,052 patients, a record unsurpassed by any other evacuation hospital in the Mediterranean or European theaters of operation.

Mrs. Lehmann retired as superintendent of nurses in 1943. Zora McAnelly Fiedler was appointed her successor (Figure 8). Mrs. Fiedler was responsible for both the nursing service of the hospital and the education of student nurses (48). She began using the title of dean of the school of nursing, since one of her major responsibilities was the education of nurses. Mrs. Fiedler campaigned for improvement of BUSN and for development of a school of nursing that was collegiate in more than name only(49).

Figure 8.

A 1997 photo of Zora McAnelly Fiedler, superintendent of nurses 1943–1947; dean of BUSN 1943–1951.

One of Mrs. Fiedler’s first tasks was the separation of nursing service and nursing education. The responsibilities of the superintendent of nurses were revised beginning with the 1947–48 fiscal year. Mrs. Fiedler remained dean of the school of nursing, and Mildred McGonagle became director of nursing services at BUH. The hospital paid the school for services of the students; the school paid the hospital for services provided to the students. Nurses serving as faculty were responsible for teaching students and had no responsibilities to the nursing service of BUH (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Nursing instruction in the 1940s. (a) Students in a microbiology laboratory. (b) Students in an obstetric nursing class taught by Miss Margaret Nelson.

Mrs. Fiedler devoted her efforts to managing the school and developing a baccalaureate school of nursing, while Ms. McGonagle managed the provision of care to patients(50). Ross Garrett and Associates, hospital consultants, were employed to assist BUH and BUSN in developing plans for reorganization, including the reorganization of nursing services (51).

NURSING AT BAYLOR UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL AND BAYLOR UNIVERSITY MEDICAL CENTER: 1950–1980

In the 3 decades between 1950 and 1980, BUH continued to expand and broaden its diagnostic capabilities and patient care services. Under the leadership of a very able group of Dallas trustees of BU and of Boone Powell, Sr., who had become executive director of BH in 1948, the hospital grew into a major community hospital and was gradually converted into a comprehensive medical center. The institution became BUMC, a regional referral center offering care in virtually all medical and surgical specialties as well as undergraduate medical student junior year rotations; internships and residencies in the major specialties; continuing education for physicians, nurses, and technicians; and support for research of medical staff members.

Even though BUCM had been removed to Houston in 1943 and the Baylor-in-Dallas concept gradually evaporated without the presence of a medical school or BU financial support for professional activities in Dallas other than BUSN, the hospital and the nursing school continued to work closely and cooperatively, even after the office of the school’s dean was moved to Waco in1951. Each was highly dependent on the other, and each held the other in high regard. As inevitable problems arose, the nursing school and hospital faced them together.

Nursing shortages were common in Dallas and across the nation during the late 1940s and 1950s. Within BUH the shortage led to concerns on the part of the administration and dissatisfaction on the part of the medical staff and patients. While BUH and BUSN jointly strove to alleviate the nursing shortage, it seemed that they would never be able to do so to the satisfaction of physicians.

At one heated meeting of the medical staff with top administrators in attendance, a very senior physician expressed complaints about the persistent lack of “dedicated nurses.” He concluded his remarks with the rhetorical question: “Whatever happened to the dedicated nurse?” Mr. Powell’s response—perhaps apocryphal—was: “I’ll tell you what happened to the dedicated nurse! During the war the dedicated nurse and the dedicated doctor eloped. And neither has been heard from since” (52).

The nursing shortage was not alleviated by expansion of hospital and university nursing education programs. Practical nursing training increased greatly during this time to provide care for patients in hospitals as well as in home care and in long-term care institutions. Prior to this time, only 36 schools of practical nursing had existed in the USA. Between 1948 and 1954, some 260 more were established. Duties of practical nurses were expanded. By 1952, 56% of the BUH nursing staff members were practical nurses rather than registered nurses (53).

A technician nurse program was recommended and adopted in which the student would study practical nursing for 1 year followed by a 6-month internship. Initially this program was administered by BUSN, but it was soon placed under the BUH nursing administration service with Mary Watts and Louise Ramsey in charge. The primary objective of the new program was to fill the shortage of personnel in the hospital and to train nurses for home nursing, with a focus on establishing unity between professional nurses and nurses’ aides (54).

Nursing duties remained consistent, with an emphasis on care of the patient. The Nightingale Hospital unit of BUH broke all records for numbers of patients admitted. The numbers were so great that patients were placed in the halls because rooms were full (55). The Truett Hospital component of BUH, upon completion in 1950, was dedicated with a prayer that God would grant “gentleness and understanding to the nurses.” The new building provided operating room facilities complete with air conditioning as well as a larger number of private and semiprivate patient rooms (56) (Figure 10). An ice-shaving machine and oxygen carts made tasks easier for nurses (57).

Figure 10.

A nurses station in the newly opened Truett Hospital, 1950. Rooms and stations were equipped with nurse call buttons for the first time.

The 1950s brought continued progress in nursing services. Formal orientation for employees began in 1951. The first orientation consisted of lectures as well as pictures of each department and a tour of BUH and the component hospitals (58). Nursing stations replaced desks in the hallways of the Florence Nightingale Hospital the following year (59).

The postgraduate practical nursing program (actually advanced vocational training) continued to provide nurses for BUH as well as other hospitals. A refresher course for nurses returning to work after years of absence was also established (60). Institutes on nursing began with the purpose of providing continuing education for nurses. Each institute lasted 8 hours and was offered 2 times (61). Florence Nightingale Hospital was demolished in 1956, and construction began on a new women’s and children’s hospital (subsequently named Hoblitzelle Hospital) (62).

The role of nursing changed as conditions affecting the hospital and health care changed. More and more patient care was provided by practical nurses, nurses aides, and newly developed specialized health care workers such as respiratory therapists. The professional nurse was spending more time in administrative duties and supervising other personnel. As medical practice changed, so did nursing responsibilities (63). In an effort to provide better patient care and utilize available personnel skills and time most efficiently, team nursing was instituted in 1958. This approach provided the professional nurse greater opportunity to give direct care to selected patients and to make and act upon clinical decisions. Patients were assigned to staff members according to the needs of the patient and the skills of the personnel available.

At the end of the 1950s, a nursing shortage still prevailed. Mr. Powell provided a detailed report to BUH’s trustees and at the meeting on December 17, 1959, discussed a “program currently under way to attract more nurses to the hospital.” The program used the nursing institutes to highlight the advantages of nursing at Baylor and living in Dallas, with the goals of both attracting new nurses and retaining the ones who were already there (64).

In spite of a growing need for nurses, BUSN continued to struggle financially. The lack of financing was so severe that in March 1960, Dr. Abner McCall, president of BU, announced that with the approval of the Waco Board of Trustees, he was investigating closing BUSN. The Christian Education Commission of BGCT wanted to maintain the school but could not commit funds for it. The Dallas executive committee expressed commitment to keeping the school open. Sources of funding were sought, and eventually BUMC agreed to contribute $10,000 for each year that the school was able to secure $20,000 from the State Mission offering (65). Thus, BUMC support was again provided for BUSN, as it would be in later decades in recognition of the need to have well-educated nurses to serve the people of Texas, including patients of BUMC and eventually BHCS-affiliated institutions.

National concern about a physician shortage as well as a shortage of nurses grew during the 1950s and 1960s. In 1963, Congress adopted the first of a series of measures to aid and expand education in the health professions. Medical schools and nursing schools generally participated in and benefited from these programs, which developed skilled professionals to help meet the growing needs and expanding expectations of the American people. Policies of the BGCT, however, constrained their use by BUSN and BUCM (in Houston), just as they constrained acceptance by BUH of Hill-Burton funds for hospital expansion (66).

In 1962, Mr. Powell described for a subcommittee of the Dallas executive committee the shortage of nurses that existed at the medical center. He noted that the shortage had developed for several reasons, including the national shortage of nurses. The situation was particularly acute in Texas, which had only half as many nurses as the average number for the rest of the country. Moreover, BUMC lost nurses every year during the summer months but had in the past been able to make up for the loss by hiring more nurses in the fall. In fall of 1962, however, the expected increase in nurse applications did not occur, while the attrition rate continued as usual. Without the employment of new nurses, those nurses remaining on the staff were required to work much harder and longer hours. This situation had worsened since the opening of the ICU in April 1962. Many nurses became discouraged and, it was feared, would resign unless the situation was corrected.

Mr. Powell went on to show data indicating that at least 30 more RNs were needed to provide patients with the desired quality of care. He described programs used at other hospitals to retain nurses, including the use of part-time nurses who worked only 1 or 2 days per week. Mr. Powell also outlined for the committee the programs and activities available at Baylor for nurses. He felt that these programs were not equaled by any other hospital in the country. He described in some detail educational activities, professional growth opportunities, and recruitment activities. After Mr. Powell made specific recommendations to increase salary ranges, noting the necessary corollary increases in room rates, the committee approved the new salary ranges and rate increases to be effective December 1, 1962 (67).

From 1963 through 1965, Mr. Powell led a comprehensive long-range planning effort designed to transform the hospital into a comprehensive medical center. Appreciating fully the importance of nursing to the development and effectiveness of patient care at BUMC, he saw to it that nurses were well involved in the planning. The approach to planning—making use of a large number of multidisciplinary committees and task forces—called for nurses to be members of many of these groups along with physicians and administrators (68).

By the late 1960s, a unit manager system was employed to free nurses from administrative duties such as supervision of aides and ordering supplies. Most unit managers were in medical areas (69).

Advances in medical technology and medical practice made essential the development of specialty nursing. Dialysis nursing began with the acquisition of BUMC’s first dialysis unit in 1960(70). An operating room nurse internship was developed in which the nurse spent 8 months learning operating room duties. By 1969, the operating room training program at BUMC was considered one of the better ones in the country. ICUs were established to provide places for critically ill patients to receive specialized attention and constant supervision. The coronary care unit was BUMC’s first ICU. Other ICU units were opened as needed, including medical, surgical, neurological, transplant, and neonatal units. Telemetry units provided intermediate care for patients at a level of intensity between the levels of the ICUs and regular patient units. Oncology nursing was instituted in 1979; enterostomal nursing was instituted the same year, with Vera Stewart becoming the first enterostomal nurse.

David Hitt succeeded Boone Powell, Sr., as executive director of BUMC in 1975. During his tenure he supported the development of specialized nursing and the establishment of specialized nursing units within BUMC.

The development of specialized nursing paralleled the development of medical and surgical specialties at BUMC. Recognition of the medical and nursing skills needed in specialized fields contributed to regional and national recognition of BUMC and development of BUMC as a referral center.

NURSING AT BAYLOR UNIVERSITY MEDICAL CENTER: 1980–2000

Between 1980 and 2000, BUMC continued to develop as a major medical center and was the nucleus around which a diversified, comprehensive, and gradually integrated health care system was developed under the executive leadership of Boone Powell, Jr., who became president of BUMC in 1980. Nursing developed separately and differently at BUMC than at the many components added to create, expand, and diversify BHCS during the 1980s and 1990s. Toward the end of the 1990s, however, professional and administrative nursing services were increasingly integrated across the health care system.

Shortage of nurses and intensifying nursing responsibilities continued to be a concern throughout most of the second half of the 20th century, especially in the final 2 decades. Robert A. Hille, senior vice president of BUMC, testified at a hearing held by the National Commission on Nursing on March 3, 1981, about the nursing shortage, its impact in Texas, and some of the actions being taken by BUMC to alleviate the shortage. His testimony noted that nursing turnover rates were high and that nursing was losing some of its appeal as a profession, as shown in declining enrollment at nursing schools. He also cited the high number of trained nurses who were not, for various reasons, working as nurses. He noted the persistent nursing shortage at BUMC, stating that the number of RN openings averaged 120 to 140.

Mr. Hille described a survey that identified nurses’ chief concerns as staffing, scheduling, support services, benefits, and incentives. Staffing was far and away the main source of dissatisfaction among the nurses. They were overworked; their morale was suffering, and they feared they would make critical errors in administering medications or have other lapses in nursing judgment that might adversely affect patients. Nurses were also dissatisfied with the promotion system, which was tied only to supervisory responsibilities.

Mr. Hille went on to describe strategies used at BUMC to keep skilled RNs, including formation of a pool of “special-needs nurses.” Innovations in scheduling and staffing also included institution of 12-hour shifts in some divisions, adoption of modular nursing throughout BUMC, and changes in weekend staffing. A midyear pay raise was granted. He also described improvements in the orientation system for nurses recruited from the Philippines. He made clear the concerted effort that had been made by nursing leadership to respond to the concerns of nurses (71).

Two of the distinctive and highly successful efforts to alleviate the nursing shortage at BUMC described by Mr. Hille in his testimony are very important to the history of nursing at BUMC and within BHCS: the two-days alternative and recruitment of nurses from abroad, especially the highly beneficial recruitment of nurses from the Republic of the Philippines.

Two-days alternative

To help alleviate the persistent nursing shortage and decrease nursing staff dissatisfaction with schedules, BUMC began an innovative approach to weekend staffing in 1981. A two-days alternative plan was implemented, which gave nurses the choice of working two 12-hour shifts on weekends (and receiving pay for 36 hours of work or 40 hours for the night shift) or working five 8-hour days Monday through Friday.

Shirley Shofner, who began as a nursing administrator at BUMC in 1973, was in the late 1970s and early 1980s increasingly concerned about nurse recruitment and, like her colleagues, frustrated by the problems that seemed to defy a solution to the persistent nurse shortage. She recalled that, at some time in 1980, Carlos Maisa, then director of management development at BUMC, brought her a journal article describing how a rubber plant in Akron, Ohio, had solved its staffing problem. The plant created a weekend alternative under which an employee was given 32 hours’ pay for 24 hours’ work if the employee would agree to work 12-hour shifts on Saturdays and Sundays. Two weekends per year were provided as vacation time with pay. Those in the 24-hour weekend positions were treated as full-time employees and received full benefits.

Ms. Shofner and Mr. Maisa worked with the other nursing directors to calculate that the cost of implementing such an option at BUMC would add about $5 per patient day to BUMC’s operating costs. Having spent thousands of dollars in domestic and overseas recruitment of nurses, they believed that the additional direct cost would be justified if the nursing shortage problem could be solved or even alleviated.

The BHCS management council, which included the most senior BUMC and BHCS executives, agreed to try the plan, assigning Robert Hille the responsibility for detailed development and implementation.

The two-days alternative plan was advertised in the Dallas Morning News. Only a small response had been expected, but the day the advertisement appeared, the nurse recruitment office was overwhelmed with telephone calls from nurses who were interested in working under the plan. The heavy response continued for days, and by the end of a month the weekend staffing shortage no longer existed. In addition, weekday staff members no longer were required to work on weekends on a rotation basis, a freedom unheard of for hospital nursing staff members. BUMC had tapped a tremendous staffing source: students attending schools and mothers with small children. A side benefit was a group of weekend nursing staff members who were willing to work at least occasionally during the week as needed (72).

The plan did require a larger total number of nursing staff members. Prior to establishment of the plan, Baylor had a 32% per year turnover rate among nurses and an average of >120 vacant positions. Within 1 week after the plan was announced, >600 nurses inquired about working weekends. Over 200 were hired, and all weekend positions were filled (73). The Baylor Plan was soon copied by many hospitals across the nation and abroad, with newspaper and journal recognition in Canada, England, and Egypt as well as in the USA.

While the plan cost BUMC an average of $5 per patient day, it reduced job dissatisfaction and turnover among nurses. Savings in costs of recruiting and orienting new replacement employees offset the added cost of the plan (74).

Linda Henson Plank, in a 1984 article in American Journal of Nursing devoted to the two-days alternative, reported, “Although there has been no formal study of the Two-days Alternative plan’s impact on either patient care or nurses’ job satisfaction and quality of life, nursing administrators [at BUMC] believe that staff morale has improved and physicians report improved relationships with nurses.” She continued, “Now, after three full years, the plan devised to solve Baylor nurses’ two main job complaints—inadequate staffing and inconvenient scheduling—is considered a definite success” (75).

The plan has continued in use and has weathered many challenges. While other Dallas-area hospitals have had staffing shortages, BUMC and other BHCS hospitals have continued to be well staffed with RNs in most areas. Over the 20 years since the plan was implemented, a high percentage of the nurses hired in the first month of the plan have continued as weekend employees (72, 76, 77). At the close of the century in 2000, 334 fulltime equivalent (FTE) nurses were working under the two-days alternative in BUMC and other components of BHCS.

In addition to the two-days alternative, a BUMC-wide preceptor program was implemented to aid in nurse recruitment and retention. Externships were developed and offered to nursing students during the summer so they could learn more about specific areas of nursing while providing supplemental help to the staff of the specialty unit (78). A day care center was established at BUMC to make it easier for nurses and other employees to work on a full-time or part-time basis while their young children were conveniently cared for.

Recruitment of nurses from abroad

A nationwide deficiency of qualified nurses in the early 1970s prompted BUMC to recruit nurses in other countries. Robert Hille, Julia Ball, and Dr. Andrew Small III made recruiting visits to the Philippines. Phyllis Walk led a group to recruit in England, Scotland, and Ireland. Others visited Canada, Australia, and New Zealand for similar purposes. Steven Wakefield of the legal firm of Wakefield and Ryburn assisted in gaining legal clearance from the US Immigration and Naturalization Service. In addition, the governor of Texas was called upon to provide assistance in licensing nurses from foreign countries.

Nurses recruited from outside the USA were brought to BUMC with 1-year commitments. These nurses proved to be valuable additions to the nursing staff, and many of even the earliest recruits continue to serve in positions of responsibility.

Recruiting nurses from other nations has been and continues to be important to provide adequate numbers of nursing staff at BUMC and other BHCS hospitals. Foreign-trained nurses, moreover, can provide far more than needed numbers of nurses. They have been demonstrated to bring high standards of professionalism as well as alternative approaches that can be drawn upon in developing new and better services. Also, most provide cultural understanding and language skills that can be invaluable in caring for patients who come to BUMC from among Texas’ increasing foreign-born population as well as the increasing numbers of patients who come from abroad for medical care.

Recruitment of nurses from the Republic of the Philippines has over the decades been the most productive of BUMC’s various foreign nurse recruitment efforts. The companion piece to this article provides more detailed information about the personal and professional lives of Filipino nurses at BUMC and the BHCS community medical centers.

Administration of nursing services

As BUMC’s leaders sought innovative ways to cope with the perennial nursing shortage, they also sought ways to improve the administration of nursing services. This was especially important as the number of nurses employed grew, the number of nursing specialties was expanded, and the number of facilities—hospitals on BUMC’s Dallas campus—continued to increase. Julia Ball, director of nursing in the Hoblitzelle Hospital unit of BUMC from 1974 until 1985, recalls having the opportunity to implement modular nursing in Hoblitzelle Hospital, participate in planning and implementing BUMC’s two-days alternative, develop a certificate of need application for a special care nursery, design the special care nursery, and do preliminary planning for nursing units in the new Roberts Hospital (79).

The administrative structure of nursing at BUMC evolved from having a superintendent of nurses and unit supervisors in the earliest days. As new hospital buildings were added on the Dallas campus, nursing services developed on a decentralized basis. Nursing in each hospital was organized under a director of nursing who reported to a hospital administrator. The hospital administrator was generally a graduate of a master’s degree program in hospital administration (MHA or MBA). There was no senior nursing administrator responsible for nursing throughout BUMC and its component hospitals or for nursing service in the specialized hospitals that were added on to the Dallas campus adjacent to BUMC itself. And as Baylor medical centers in communities surrounding Dallas were added to BHCS, nursing services were supervised by nursing administrators responsible to the local Baylor medical center administrators.

Upon becoming president of BUMC in 1980, Boone Powell, Jr., saw the need for BUMC to have a chief nursing officer and urged changes that would move toward that goal.

In 1984, the internal administration of BUMC and its component hospitals was reorganized in a process overseen by Robert Hille. For the first time, nurses with master’s degree qualifications in nursing were appointed as the hospital administrators responsible for nursing services in Collins, Jonsson, and Hoblitzelle hospitals and the new Roberts Hospital, all components of BUMC. At the same time, Dr. Eula Das, the first doctorally prepared RN at BUMC, was appointed vice president for hospital operations encompassing nursing services throughout BUMC (80). This was a major move in the direction intended by Mr. Powell. Dr. Das did not, however, have jurisdiction over nursing services in the specialized hospitals on the Dallas campus or at community medical centers.

Traditionally, advancement for nurses meant moving up the administrative ladder. Many nurses, however, enjoy patient care and do not wish to leave the nursing floor. Dr. Das developed a career ladder to provide recognition of excellence in nursing care. Nurses were classified as clinical nurse I, clinical nurse II, or clinical nurse III according to defined criteria and achievements. Salary and other benefits were adjusted accordingly. Participation in the career ladder was voluntary. Points were awarded according to activities such as leadership, education, teaching, professional certification, research, and service activities (81).

Positions changed as the needs of patients and demands of the health care system changed. Case managers, quality care coordinators, and other specialists and supervisors were added to the list of nursing roles at Baylor. Advanced practice roles were also integrated into nursing services. The first advanced practice nurse was a nurse-midwife who was employed in the 1970s. The first clinical nurse specialist was Ann Collins-Hattery, who was added to the oncology unit staff in the 1980s. Today many clinical specialists are employed at Baylor, including master’s degree–prepared clinical specialists in cardiovascular medicine, diabetes, and other specialties. Transplant nursing debuted in 1985 and grew as the transplantation service grew in terms of types of organs transplanted at BUMC and numbers of patients served. With the advent of the Baylor Senior Health Centers in 1993, nurse practitioners (NPs) began to provide care along with physicians to senior citizens in the community (82). Today NPs with specialties ranging from neonatology to gerontology work in many areas within BUMC and other BHCS-sponsored entities.

Nursing at Baylor has long been dedicated to providing service to the public as well as caring for patients. Community outreach services include many volunteer activities by nurses, some of whom are working on career ladders.

Home health care provides an outreach to patients who could be cared for while remaining at home. Initially, both BHCS and BUMC offered home health services that employed nurses. Eventually a separate company, Baylor HomeCare, was established to provide home health services, with Shay Fields as managing director; nurses were employed in key roles, including Ruth Whitaker as director of Dallas operations, Lynn Gill as director of community office operations, Carrin Feagins as director of quality improvement, Nancy Stretch as supervisor of intravenous nursing, and Toni Allen as director of pediatric home care.

As the home health care service market in the Dallas area changed, this component of the health care industry was restructured. BUMC’s home health care company was sold in 2000 to a larger company serving a broader geographic area.

International assistance in nursing

BUMC’s nursing outreach has been extended internationally. BUMC nurses participated in an assistance project in Romania instituted in 1991. Boone Powell, Jr., and David Jones, chairman and CEO of Humana, Inc., had been asked by President GeorgeH. Bush if their institutions would aid a former communist bloc nation in increasing the quality of health care. Romania and nursing were chosen as the focus of the project (83). An initial fact-finding visit was conducted by a BUMC team that included Dr. Carolyn Banks, director of BUMC nursing research and education, and William Denton, assistant vice president of BUMC for operating room services. The purpose of this project was to provide continuing education for Romanian nurses and to help implement new health care technologies in Romania. In the first phase of the project, 8 Romanian nurses spent 7 months at BUMC focusing on 1 of 4 specialty areas: community health, nursing management, nursing education, and psychiatric/mental health nursing. Training was offered through both classroom instruction and clinical experience (84).

After the nurses returned to Romania, a team of 8 to 10 American nurses, including Margaret Cain of Humana and William Denton from BUMC, traveled to Romania to conduct continuing education classes for nurses there (Figure 11). Senior nursing staff members from BUMC who were active in developing the program included Phyllis Walk and Paula Holder. Many BUMC nurses participated in the teaching in Romania, including Rene Bailey, Rebecca Horn, John Dixon, Margaret Lathrop, Cynthia Ruddell, Sandra Martin, and Jane Whitehead, as well as Dr. Linda Garner of BUSN (85). Two team visits were made each year between 1991 and 1995. Each BUMC and BUSN nurse taught either care of the critically ill patient or infection control and communicable disease to groups of 20 to 50 nurses, and the workshops were repeated 4 times on each trip (85). Thus, >10,000 nurses in Romania received instruction through the program. After conclusion of these workshops, an institute for continuing education and a school for nurses were established in Romania by the nurses trained by BUMC and BUSN nurses.

Figure 11.

A nursing education class conducted by Baylor nurses in Romania.

The Baylor nurses found how hard it is to change long-standing practices and to induce others to change. They also learned how different it is to provide patient care with limited medical resources and with nursing staff members who are not educated and trained as they are in the USA and Western Europe. Hence, the Romanian project was a learning experience for both the US and Romanian nurses (86).