Michael Emmett (Figure 1) was born in a displaced persons camp near Linz, Austria, on October 29, 1945, and he and his family came to Philadelphia 4 years later. After attending public schools, he went to Pennsylvania State University, graduating magna cum laude in 1967, and then to Temple University School of Medicine in Philadelphia, graduating in 1971 first in his class. In medical school he received 4 major awards and was president of the local chapter of the Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Society. His internship and 2 years of medical residency were at the Yale-New Haven Medical Center in New Haven, Connecticut, and his 2-year fellowship in nephrology was at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania.

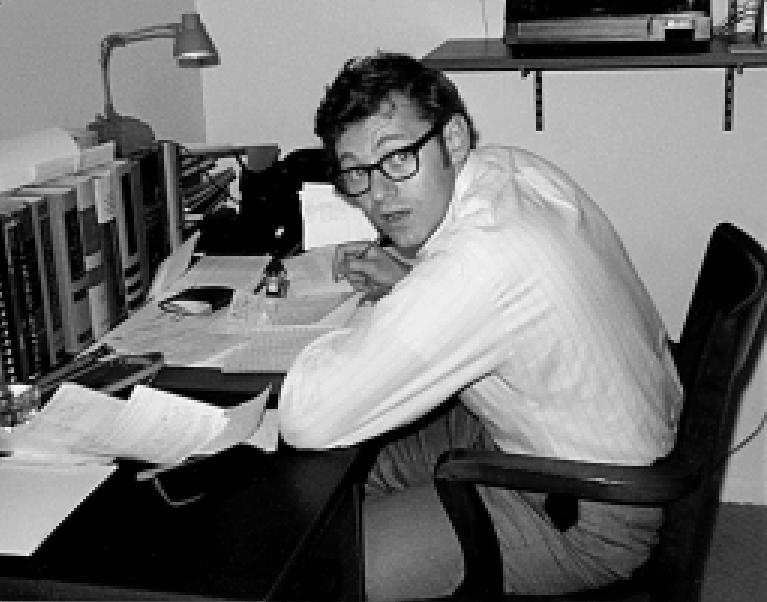

Figure 1.

Michael Emmett.

After considering a number of academic and nonacademic offers, in July 1976 Dr. Emmett joined Dallas Nephrology Associates and the staff of Baylor University Medical Center (BUMC) in Dallas. He rapidly became very involved in teaching the medical residents and nephrology fellows. Simultaneously, he attended the weekly nephrology conferences at The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and became friends with Dr. Donald Seldin, who was then chairman of medicine there. He and Dr. Seldin rather quickly started collaborating on manuscripts. In 1986, Dr. Emmett became director of the Division of Nephrology/Metabolism of the Department of Internal Medicine, the Tompsett Professor of Medicine, director of the Nephrology Laboratory, and medical director of the Ruth Collins Diabetes Center, all at BUMC. In 1988, he became clinical professor of medicine at The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. In the early 1990s, he was president of the medical staff and president of the medical board and executive committee of the medical board of BUMC. Since July 1994, he has been a member of the American Board of Internal Medicine Subspecialty Board in Nephrology. In January 1996, Dr. Emmett became chairman of the Department of Internal Medicine at BUMC and gave up most of his private practice. In March 2001, Dr. Emmett was honored by the designation of mastership in the American College of Physicians, joining a select group of 300 US physicians.

Dr. Emmett has published at least 30 articles in peer-reviewed medical journals, 11 chapters in various medical books, and 21 abstracts. His articles on the anion gap and mixed acid-base disorders, published following his nephrology fellowship, have become classics and brought him wide recognition. His studies on chronic phosphate depletion and phosphorus binders also have brought him recognition. He and his wife, Rachel, have 3 children: their daughter, Mira, is an assistant district attorney in Atlanta; Daniel is presently interning in internal medicine; and Joshua is building an Internet music company. Dr. Emmett is an outstanding chairman of medicine, a magnificent teacher, a medical scholar, and a man who cares deeply for his fellow human beings.

William Clifford Roberts, MD (hereafter, WCR): Dr. Emmett and I are in my home on March 1, 2001. He has graciously consented to talk with me and therefore to the readers of BUMC Proceedings. To begin, could you discuss your early life, your parents, and your siblings?

Michael Emmett, MD (hereafter, ME): First, Bill, thanks so much for having me over to your home. My parents were born and raised in a small rural village in Poland called Tuchin. Tiny towns such as this in Eastern Europe were called shtetls. The shtetl of Tuchin was near the Russian-Polish border and the border often moved, so the town was sometimes considered Polish and other times Russian. It is in the area of Russia now designated as the Ukraine. Because of the frequent changes in nationality, my parents were fluent in Polish and Russian. They were also fluent in Hebrew, but their native language and the language they spoke at home was Yiddish, which is a derivative of German.

I was born in the small village of Bindermichel, which is a suburb of Linz, Austria. At the time, my parents were living in a displaced persons camp. We lived there in Bindermichel for about 4 years. In 1949, my parents, my older sister, and I emigrated to the USA (Figure 2). We crossed the Atlantic on a ship called the Marine Flasher from Bremen, Germany, to Boston and arrived in January 1949. My very first memories are of the voyage on that ship. It was a stormy winter crossing of the Atlantic, and I remember staying in a bunk bed with the boat rocking all the time. When we arrived in the USA I spoke only Yiddish. My parents had virtually nothing—no money and not many clothes—and could not speak a word of English.

Figure 2.

Alien registration card allowing Michael Emmett, age 31/2, to enter the USA and become a permanent resident.

My father had a half-brother and half-sister who lived in Chester, Pennsylvania, and because they had sponsored our immigration, we went to live with his half-brother. We moved into a small basement apartment in their home. My father and his half-siblings were not close. In traditional Jewish culture, if a married woman died leaving children and she had a younger unwed sister, then that woman was obliged to marry the widower and raise the deceased sister’s children. That is what happened with my paternal grandfather. He was married to a woman who died leaving 2 children. Her unmarried younger sister was obligated to marry him and then they had 7 children together. The second woman, who was my paternal grandmother, was unhappy at having had to marry this older widower. Her older stepchildren felt that she favored her own children over them and eventually left Tuchin. In retrospect, they were quite lucky to have left Europe in the 1920s and 1930s and arrived in the USA where they were spared the horrors of World War II. These two stepsiblings were the only relatives my parents had in the USA.

WCR: Are either of your parents still living?

ME:No. My mother died in 1989 and my father in 1996.

WCR: When were your parents born?

ME:My father was born in 1900 and my mother in about 1910.

WCR: What kind of education did they have?

ME:My father was a very bright man but had very little formal education, not even the equivalent of a high school degree. Most of his education was religious education. He was fluent in Hebrew and could read and understand the Bible and various religious manuscripts in their original Hebrew and Aramaic. My father could also speak, read, and write Polish and Russian as well as, of course, Yiddish.

WCR: What about your mother’s education?

ME:She was even less formally educated than my father. In the shtetls of Poland it wasn’t considered important, or even appropriate, for women to be formally educated beyond rudimentary basics. She could read and write Yiddish and Polish but wasn’t nearly as educated in Hebrew as my father and could speak but not read or write Russian.

WCR: You say your parents were born in Poland or Russia, whatever the circumstances were at the time. How did your parents survive in the Nazi regime just before and during World War II?

ME:The Germans invaded Poland in September 1939 but did not enter the village of Tuchin until 1942. Over the next year things went from bad to worse with the Jews in Tuchin. The Germans demanded money, clothes, gold, and all jewelry. They rounded up men for forced labor. My parents and my 2 sisters were forced from their home and lived in a small room. Jews were beaten and killed regularly. Then after a year the Germans ordered all the Jews of Tuchin and the surrounding countryside to gather in a small area, which was converted into a walled ghetto. My parents were sure the plan was to eventually kill them all, and they were correct. Before the wall was sealed my parents sent my older sister Hannah to live with a childless Christian couple. The man was the principal of the school she had attended and they liked Hannah very much. She was blonde and blue-eyed, and they planned to adopt her and raise her as a Christian child.

My parents and younger sister fled to the countryside to the farm of an acquaintance. My father had been the manager of a grain mill and had befriended a Christian farmer named Pavel Gerasymchik who had brought grain to the mill (Figure 3). They were not close friends, really just business associates. Nonetheless, Pavel agreed, at great risk to himself and his family, to hide my family in a barn. They thought this would be for a few weeks or 1 to 2 months. My parents and sister were hidden for 18 months behind a hayloft. Pavel or his children would try to take them food every day. They would use a latrine late at night. Parenthetically, this farm family had a watchdog named Briscoe. Whenever strangers such as German soldiers came near the farm he would bark and thus warned my family to hide and be very quiet. We now have a chocolate lab named Briscoe, and when people wonder about the unusual name, that is its derivation.

Figure 3.

Pavel Gerasymchik, the man who hid the Emmett family during World War II.

After a few months of this hiding, the family who “adopted” my older sister became frightened that they would be accused of harboring a Jewish child. They told my sister, who was about 13 years old, that she would have to leave and seek out her parents. As she passed through the town, she was identified as a Jewish child and was shot and killed by either the Nazis or their Polish collaborators.

In late 1944 or early 1945, the Russians drove the Germans out of Tuchin. My parents and sister were temporarily elated. Then the Russians forced my father to join the Russian Red Army and sent him east into Russia. After about 4 or 5 months, he deserted and went back to Tuchin and then escaped to the west with my mother and sister. They spent several weeks in Prague. They were desperate to get into the American zone and made their way to Austria. My mother was pregnant, and I was delivered in Bindermichel, a village that had been built as housing for the families of Nazi officers. It had been converted into a displaced persons camp. I lived there from 1945 until we left in 1949.

WCR: You don’t remember anything about the camp?

ME: Not really. I do have one picture of myself and my older sister, Laura, from the camp. I am wearing lederhosen. My first memories, however, are of the Atlantic crossing in 1949. That ship was a troop carrier that had been converted into a passenger ship.

WCR: When your parents left Poland they had no money?

ME: No. What money they had had in Poland was tied up in a house. They had very little cash or jewelry, and what little they had was used to survive during World War II. My father had a gold watch and that was about it. They also had very few pictures that survived the war. My parents’ home was located in a part of Tuchin that became the Jewish ghetto, and that entire area was burned.

WCR: What about your father’s family?

ME:My father had 2 younger sisters who emigrated to Israel in the 1930s. However, his other 4 siblings, his parents, and his grandparents were all killed. All of my mother’s siblings and her parents were also killed during World War II.

WCR: How did your parents get visas to come to the USA?

ME: As I mentioned, my father’s half-brother and half-sister who resided in the USA sponsored our immigration. The decision to come to the USA was a difficult one. My father really wanted to go to Israel to be with his 2 surviving sisters. However, my mother didn’t want to go to Israel (actually it was Palestine at the time—Israel had not yet become a country) because she was sure there was going to be another war. Of course, she was right. My mother had already had her fill of war and wanted the family to emigrate to the USA, which seemed like a much safer place to live.

WCR: How did your parents get on in the USA? What was life like? What was your apartment like?

ME:During the first year or so we lived in the basement apartment in Chester. My father took a variety of odd jobs such as washing dishes and doing handy work in a restaurant. The Hebrew Immigrant Absorption Society helped my parents quite a bit. They helped my father get various jobs and gave him some financial support. At one point he actually traveled to New York City via train and buses not speaking a word of English. It was quite an adventure for him.

We then moved to an area of Philadelphia called Strawberry Mansion and lived in a third-floor apartment (Figure 4). This neighborhood had a very high concentration of Eastern European immigrants, many of whom were Jewish. Yiddish was spoken by most of these people and was often heard spoken on the streets. My father became a pushcart salesman and sold fresh fruits and vegetables door to door. He would go to the farmer’s market at 3:00 or 4:00 AM and purchase produce wholesale. He still spoke minimal English and so he would negotiate a price with hand gestures. He would then sell the fruits and vegetables that morning. Eventually he saved enough money so that he and another pushcart salesman were able to open a small corner vegetable and grocery store in the same neighborhood. Of course, we were incredibly poor, but as a child I was oblivious to all that. I didn’t have any of the usual toys but would make scooters from orange crates and rubber band guns from pieces of discarded wood. As time went by, Strawberry Mansion became an even poorer neighborhood. As soon as various families were able to move, they would leave the area, and other poor immigrants and poor blacks moved in. The neighborhood became a very dangerous place to live and, indeed, Strawberry Mansion continues to be one of the worst rundown ghetto areas of Philadelphia to this day.

Figure 4.

Michael Emmett at age 6.

WCR: Was the grammar school you went to close to your apartment? Did you enjoy school?

ME:The grammar school was within walking distance of our apartment. Initially this was an academically adequate school. However, I wasn’t a very good student. Perhaps this was in part because English was my second language and it really took me a while to catch on. My grades were very poor, with many Cs, Ds, and Fs. Teachers would often comment on my report cards that unless things changed I would never amount to much. I went to that school from kindergarten through fifth grade. As I mentioned, during those years the neighborhood deteriorated. Strawberry Mansion became a rundown, inner-city slum. The quality of the education deteriorated along with the neighborhood.

WCR: At home what language did you speak?

ME:We spoke Yiddish in the house. Although my parents were able to converse in English, it was difficult for them, and Yiddish was always the dominant language. Of course, I spoke English outside the home.

WCR: So after a while both parents became relatively fluent in English?

ME:They certainly became fluent enough to understand and read simple English sentences, but it was always difficult for them. They always maintained very heavy Eastern European accents. My parents would read Yiddish newspapers, and we never had any English papers delivered to our home.

WCR: So there was you and your sister and your mother and father? It sounds like your father was working all the time.

ME:Yes, he pretty much worked day and night 7 days a week. In Europe he had been quite religious, but when he came to this country he couldn’t afford not to work on Fridays and Saturdays. Consequently, he stopped going to synagogue. At first that was very difficult for him, but as time went by he became more used to it. Years later, as he was able to, he became quite observant and would go to synagogue 2 or 3 times each week.

WCR: What about your mother? Did she stay at home taking care of you and your sister?

ME:Yes, she took care of both of us. However, I was actually raised more by my sister than anyone else. My sister is 11 years older than I am. By the time I was 4 or 5 and she was 15 or 16, she was doing most of the things mothers usually do. Some of the rumormongers in the neighborhood wondered if I was actually her illegitimate child because she was always taking care of me.

WCR: Did your mother work in the store also? Do you remember meals at night? Was it just you and your sister?

ME:Most of the time dinner involved my mother, sister, and me. My father was often away trying to make ends meet. We would have family meals once or twice a week when my father was at home.

WCR: When did you and your parents eventually move out of Strawberry Mansion?

ME:Eventually my father made enough money to buy a larger store. Instead of selling just produce, he sold various canned goods and other groceries. He then made enough money so that he was able to purchase a larger store, which was located in Levittown, Pennsylvania. By this time my sister had married, and he opened the store in partnership with her husband. Levittown is a suburb in Bucks County, north of Philadelphia. For sixth grade I lived with my sister, who had a home in the northeast part of the city, and attended grammar school there. Then my parents bought a house in Levittown and I moved there. Our house had a lawn, and I had never really seen houses with lawns before. In innercity Philadelphia all of the homes are row houses and attached to one another. The streets are solid concrete with almost no grass. Once we moved to Levittown we had a lawn, which I was assigned to mow. I also got a dog at that time. Our lifestyle had changed dramatically. It was much more like a typical American middleclass existence. The junior high school I attended was a modern, clean building, which was also quite a change.

WCR: How did you react to the trees and grass?

ME:I loved everything about that. I soon became a Cub Scout and then a Boy Scout. I enjoyed camping and the outdoor life. However, my father was still working all the time and he was also much older than all of my friends’ dads. After my sister was married, I identified more with her and her husband than my own parents. For example, my father never took me to a baseball game or any other sporting event, or fishing or camping. I did some of those things with my brother-in-law, who was about 14 years older than I was.

WCR: Your father didn’t have time to do it himself?

ME:He didn’t have time or really the interest. He was never interested in any sporting activities, fishing, or camping. His entire life was pretty much devoted to earning a living and to religion.

WCR: Once you started school in your suburban junior high, you were about 12 years old. What do you remember about junior high school and the different atmosphere you were suddenly in? Also, how did you progress from an academic standpoint?

ME:I went from being a very poor student to an average student. I fit in okay and participated in some of the extracurricular activities in junior high school. However, I certainly didn’t stand out in any way. I enjoyed living in Levittown. It was a very nice community and I made some very good friends. We would play baseball and football games on empty sandlots on weekends. This compared with my earlier years in Strawberry Mansion, where all the games were “street games.” They included wall ball and half ball. Half ball was a game played with a sawed-off broomstick and a “pimple ball” cut in half, with rules somewhat like baseball.

WCR: You lived in Levittown 3 years?

ME: Yes, we lived there for 3 years and then my parents bought a small duplex home in the northeast suburbs of Philadelphia. My parents wanted to be closer to my sister, who still lived in that part of the city, and Levittown was a 40-minute drive. Therefore, we moved back to Philadelphia and I enrolled in Northeast High School. Once again, I was an average-to-good student but certainly not outstanding. My graduating high school class had about 750 kids. I was in the top third of the class but certainly not in the top 10% or 15%.

WCR: What did you do in high school? Did you participate in a lot of extracurricular activities? Were you an athlete?

ME:I played junior varsity football and was a linebacker. However, I wasn’t really very good. Then I fractured the ball of my left humerus, and that pretty much ended my mediocre football career. I played some sports with my friends. We had a basketball net nailed to a light pole and would play street basketball. I enjoyed bowling. From time to time my friends and I would take a camping trip or go fishing in one of the creeks around Philadelphia. I was only minimally involved in the day-to-day cultural life of my high school.

WCR: What was your house like? Were there any books around the house? Did your mother read at all?

ME:Neither of my parents read very much. My father read the newspaper and religious books. They both read Yiddish papers. The few books that were in my house were in Yiddish or Hebrew. I didn’t read in either language. Therefore, there were no books that I could pick off a shelf and read.

WCR: As you got into high school, did you have some interesting conversations around the table when your father was home from work?

ME:We’d sometimes talk about political issues, but not much else and not in great depth. Nothing very philosophical.

WCR: Who had the most influence on you, your mother or your father?

ME:Probably first was my sister and then my mother. My father had the least influence because he was around so little.

WCR: What did your sister do? She got married.

ME:She was a homemaker. She never went to college. My parents really couldn’t afford to send her to college. She married a man who later became my father’s partner in the grocery business. My sister, Laura, raised me more than anyone else.

WCR: Did she have children?

ME:Yes. She has 3 children.

WCR: They still live in Philadelphia?

ME:Yes. Two of her children are physicians—one of her daughters is a radiologist in Philadelphia and her son is a dermatologist. Her oldest child is a daughter who runs the Pharmacy Department at Pennsylvania Hospital. She recently installed a physician order entry computer in her hospital.

WCR: How did her children get interested in medicine? There are no physicians in your family anywhere?

ME:None. In part, they followed my footsteps. I certainly encouraged them to go to medical school.

WCR: Did they go to Temple?

ME:My niece went to Temple, and my nephew went to Jefferson and obtained an MD/PhD. He did his dermatology training at the Massachusetts General Hospital and then became a Mohs’ surgeon. He’s in Allentown, Pennsylvania.

WCR: What does Mohs’ surgery mean?

ME:That’s a subspecialty of dermatology dealing with the resection of skin cancers and microscopically analyzing each resected section until you have clean margins.

WCR: How was it that you went to Pennsylvania State University to college? I gather it was expected that you go to college.

ME:Yes, my parents expected me to go to college. They did not want to send my sister to college, but education of their son was important to them. I had no relatives or friends or really anyone to speak with about college. I’d been a decent high school student but certainly didn’t excel. I wasn’t offered any scholarships. I didn’t know anything about colleges or college life. The only colleges I ever even considered were the 2 state colleges in Pennsylvania—Temple and Penn State. I wanted to get away from home and get out into the countryside. That’s why I chose Penn State. However, my first year I attended the Penn State campus in Philadelphia (Ogontz campus) because my parents wanted to see how things would work out and it was much cheaper. That was a major issue.

WCR: You lived at home that first year?

ME:I lived at home and commuted to college. This was the first time I excelled academically. I’m not sure what changed from high school to college, but I really enjoyed the classes and suddenly I found my niche. I loved the sciences and mathematics in college. My chemistry teacher, Mrs. Nutting, gave me a lot of strokes. I’d get the highest grades in the class on many tests. I also did great in physics and math and just loved those courses. I excelled on the little Ogontz campus of Penn State. I was a big fish in a very small pond.

WCR: And all of a sudden you liked it.

ME:I really enjoyed it. I got great positive feedback from the teachers at college.

WCR: How far was college from home? You had to commute?

ME:It was a 35- to 40-minute drive. A group of about 5 of us lived in the same part of Philadelphia and carpooled. We commuters came to be good friends.

WCR: Did you have to work during that year, or did you have enough money to go without working?

ME:I didn’t work because tuition was about $200 a semester. The entire first year couldn’t have cost my parents more than $1000 to $1500.

WCR: This was what year?

ME:This was 1963. I remember President Kennedy’s assassination report while I was driving to the Ogontz campus.

WCR: How did you switch to the state college campus the next year?

ME:I convinced my parents to let me go to the main campus. By that time my father’s business was successful enough so that he could afford to send me to an overnight state college. Tuition was still very inexpensive. Of course, now I had to pay for room and board. I didn’t have a car. Some of my friends had wealthier families, and they had cars. I lived in the dorms my second year of college. That was a wonderful experience. I liked living at Penn State. The campus is beautiful. I continued to do very well academically but was no longer the very best in each class. I was a very good student.

WCR: Did you have to study hard or did it come easy for you?

ME:I studied hard but I enjoyed it. I especially enjoyed science and math. It wasn’t drudgery or work for me to do it.

WCR: This was your first time away from home?

ME:Yes.

WCR: Did meeting classmates who had very different backgrounds open your eyes?

ME:It did. I really had lived a very sheltered existence with a small group of friends. It was interesting to meet people from around the state. Penn State football games on Saturdays were a big deal. We’d always go to the stadium and cheer the team on. I wasn’t involved with fraternity life, which is very big at Penn State. I didn’t have any concept of what a fraternity was. By the time I had become a senior, I’d go to an occasional fraternity party because some of my friends were members. But that was my only real fraternity experience. I began to date Rachel, whom I met during my junior year of college. She’d come to Penn State occasionally for special weekends and stay with her girlfriends.

WCR: What is the age difference between you and Rachel?

ME:Four years.

WCR: How did you happen to meet?

ME:My sister introduced us. Rachel’s brother had an appendectomy and was recovering on the same floor as my brother-inlaw, who had had a gallbladder operation. My sister met Rachel and her parents, and she suggested we get together. It turned out that she lived only about 5 minutes from my house, but I had never met her until the meeting at the hospital.

WCR: Where did she go to college?

ME:She went to Temple.

WCR: What is her background like?

ME:Rachel’s parents were also Jews who survived the war in Europe. Unfortunately, they were captured and placed in concentration camps. Her father survived internment in 11 different concentration and forced labor camps. He has a blue number tattooed on his left forearm as a permanent reminder of his time in Auschwitz. He met Rachel’s mother after the war. They were determined to get to Israel, and their postwar experience was very much like the movie Exodus. They boarded an old, leaky ship that attempted to get through the British blockade of Palestine. The British stopped the boat and boarded it and then diverted it to Cypress. They lived in a tent city in Cypress, and that is where they were married. Eventually they did get into Palestine, and her father fought in Israel’s War of Independence in1948. Rachel was born in Israel. Later they emigrated to Canada and then in 1956 to the USA.

WCR: What did Rachel major in?

ME:She was a math major. After she graduated she worked as a computer scientist.

WCR: When you met Rachel, you were a junior in college and she was a senior in high school?

ME:She had just graduated from high school.

WCR: She was at Temple when you finished your last year of college?

ME:Yes. We were married in 1969 after my second year of medical school. She graduated and supported us by working for the Federal Reserve Bank as a computer systems analyst.

WCR: You mentioned a Mrs. Nutting who was a confidence builder for you in college. Did you have any other mentors in high school or college who really had an impact on you?

ME:Not really. As I said, in college I began to do quite well in some of my course work and I got positive reinforcement from various teachers, but I never really had a mentor who took any special interest in me. I never went to their houses or had any one-on-one conversations.

WCR: When did you decide you wanted to be a physician?

ME:In the Jewish tradition, the physician is a very respected and highly regarded individual. My parents wanted me to become a physician, but I wanted to be a scientist. I thought I might become a chemist or a physicist. However, by the time I was in my junior year of college I had decided to go to medical school. I’m not sure how much of that was my parents’ brainwashing and how much was because I had decided that it was what I wanted to do. I did enjoy both the biological and physical sciences.

WCR: You picked Temple. Did you apply to other medical schools?

ME:It was similar to college. I didn’t have a wide horizon. I applied only to the 5 medical schools in Philadelphia. I didn’t get into the University of Pennsylvania and I would not have been able to afford to go there without a large scholarship. I had to pick a school that either was going to give me a scholarship or was relatively cheap. Temple was a very inexpensive state medical school. I got into the other 3 schools and chose Temple. I lived at home until I was married. I moved back home from college and commuted to medical school. It was a very inexpensive proposition. Medical school cost <$1500 a year. I didn’t have a car. I’d usually take 3 buses or get a ride with friends.

WCR: You started medical school in 1967. How did medical school hit you? Did you enjoy it right from the beginning, or how did it work out?

ME:I did very well and enjoyed it (Figure 5). I always liked analytical courses much more than those requiring memorization.

Figure 5.

Michael Emmett in medical school in 1970.

Therefore, I did not like anatomy or histology too much. I did fine in those courses but I didn’t particularly like them. I loved physiology, biochemistry, and pharmacology. I enjoyed the labs in those courses. After I got onto the wards in my third and fourth years, I really enjoyed the clinical aspects of medical school.

WCR: Who had a major impact on you in medical school?

ME:Again, there wasn’t any one person. In the preclinical years I did very well, and by the end of the second year I was ranked first in my class. Although we didn’t have a formal publicized ranking system, they gave an award called the Roche Award (it is a gold watch) to the top-ranking medical student after 2 years. I was surprised when I received that award. I knew I was doing well, but I didn’t realize I was first in the class. Our medical school had about 100 students in each class, so I was able to interact more with some of my professors than in college. In the clinical years, the person who had the most impact on me was a nephrologist named Leroy Shear. He was a brilliant teacher, and all of us were so impressed with him. He would come up with the most interesting analyses and diagnoses. After spending 6 weeks with him, I decided to become a nephrologist.

WCR: Where did you and Rachel live after you got married?

ME:We lived in a small apartment. After we married, we finally got a car. Rachel would drive the car to work and I took the subway.

WCR: You got your first car after your second year in medical school?

ME:Our first car was a wedding present from my parents in1969.

WCR: Surgery just had no appeal for you?

ME:Not really.

WCR: Did you enjoy pathology?

ME:I enjoyed it but not as much as the other analytical basic sciences. Pathology had too much memorizing and identification.

WCR: It must have been a tremendous confidence builder for you to be first in your class in medical school when you really hadn’t thought that much of studies until that point.

ME:It was an amazing metamorphosis. I had never excelled to that degree at any academic level. When I received the Roche gold watch, I was really surprised. I still wear that watch. That was a huge confidence boost. I later received a number of academic awards, but that first was a heady experience for me.

WCR: How did it come about that you went to Yale for your internship?

ME:Although my horizon had expanded a little bit, I was still very much a Philadelphia boy. Rachel and I had rarely traveled far from Philadelphia. We had been to New York City a couple of times. State College was the farthest west we had ever been. I had never been to Boston. California was the other end of the world. I applied to a number of programs along the East Coast: Massachusetts General and Beth Israel in Boston, the Johns Hopkins, University of Pennsylvania, Yale, and Temple. I ranked Yale third behind the Massachusetts General Hospital and Beth Israel. I didn’t think I’d get into my first 2 choices. Even though I was first in my class, Temple was not considered an outstanding medical school, and I hadn’t done any exciting research as a medical student.

WCR: How did Yale work out?

ME:I was initially excited but later a bit disappointed. One reason I ranked Yale high was its very strong nephrology division led by Frank Epstein. Another thing I liked about Yale was the chief of medicine, Phil Bondy. He had interviewed me in his inner sanctum on a cold snowy day in New Haven. There was a big roaring fire in his office fireplace, and Dr. Bondy smoked his pipe. He told me that I was the kind of guy he needed at Yale. Nobody had told me that at Hopkins or the Massachusetts General Hospital. I really had a good feeling about Yale. The match letter came one day and the next day or so I received a letter from Dr. Bondy saying he had resigned as chief of medicine and was going to England for a 1-year sabbatical. When I arrived at Yale, Frank Epstein was still there, but he soon left to become chief at the Boston City Hospital and took a number of nephrologists with him. I was disappointed about those events, but Yale was still a wonderful experience. The faculty was still spectacular. My peer group of medicine interns were students from Harvard, Penn, Yale, Hopkins, and Dartmouth. It was wonderful putting flesh and bones on the images I had of persons from such places.

WCR: Who were the people who had a major impact on you when you were in New Haven at Yale?

ME:Jerry Klatskin had become the acting chief of medicine. To this day, he remains the best clinician I’ve ever met. He was also a great raconteur, telling great stories and jokes. After Dr. Bondy returned, he had significant influence, as did Louis Welt and John Hayslett.

WCR: You enjoyed the atmosphere, the milieu very much.

ME:Yes, but it was occasionally a little rough. Lou Welt came from Chapel Hill to be Yale’s new chief of medicine. We were very excited when we heard he was coming, but his tenure at Yale turned out to be a disappointment. He was ill and depressed when he arrived. He had personal family problems that affected his performance. I hoped his arrival would improve the nephrology division, but that didn’t happen. That’s why I decided to leave Yale to pursue renal fellowship training elsewhere.

WCR: Why did you choose the University of Pennsylvania for your fellowship?

ME:I thought it was the best nephrology program in the country at that time. I had never heard of Southwestern in Dallas. If you had mentioned the name Southwestern to me, I wouldn’t have known what state it was in. Dr. Seldin has told me that the biggest professional mistake I made was not coming to Southwestern for my renal fellowship. He said he could have made something out of me if he had gotten ahold of me in my formative years. He is probably right. Nonetheless, Penn was wonderful. Arnold Relman was the chief of medicine; Sam Thier was his number 2. Marty Goldberg was the chief of nephrology, and there were many other wonderful nephrologists at Penn.

WCR: Your fellowship was for 2 years?

ME:Yes, 1 clinical year and 1 research year.

WCR: What did you work on?

ME:My first year was all clinical, and there were 4 other first year fellows. The second year I chose to work in Relman’s laboratory. Unfortunately, Relman was gone the entire year (in England on sabbatical), so I didn’t have the opportunity to see him very much. Bob Narins ran Relman’s lab, and he was my research mentor. I was supposed to set up an isolated perfused kidney model, but that never really worked out. We did a number of in vivo acid-base experiments in rats, and I became adept at rat surgery, intubating them, putting them on ventilators, and cannulating renal arteries and veins. We then produced various acid-base abnormalities and studied the effect on renal acid excretion. That led to several publications.

The one thing that helped define my later career was an event that occurred late in my first year of fellowship at a weekly “Fluid Rounds” conference. Each Friday, wine and cheese were served and Drs. Relman, Goldberg, Narins, Thier, Donna McCurdy, Irwin Singer, Stan Goldfarb, Zalman Agus, Lee Henderson, and others discussed and argued the fine points of various interesting cases. One day I walked into this conference and a chemistry profile was on the blackboard. Ralph DeFronzo, who is now in San Antonio and was then a research fellow, walked into the room, looked at the blackboard for about a minute, and said, “Another case of multiple myeloma.” I looked at the chemistries and couldn’t begin to figure out how Ralph knew that. The patient’s calcium was about 11 mg/dL and his anion gap was –2. I was clueless about what a negative anion gap meant. Ralph explained it to me.

At the start of my research fellowship I said to Narins, “You know, Bob, I don’t think this isolated perfused kidney project is going to work out. I’ve only got 1 year to set it up, and I am not a good glass blower. I don’t want this year to be a total waste. Why don’t I also work on some clinical project so I can generate at least 1 manuscript? I don’t understand this anion gap. Let me work on that.” He agreed it was a good idea. I spent August as a camp physician in upstate Pennsylvania. I took a stack of articles with me and in my spare time read about the anion gap. I wrote a manuscript that was published in Medicine in 1976. That article and a follow-up companion piece called “Simple and mixed acid-base disorders: a practical approach” helped determine my future career. The articles became very well known among medical students, fellows, and residents. I had also published a research article in the Journal of Clinical Investigation on the acid-base effects of phosphorus depletion. Dr. Seldin had read that article and therefore knew who I was when I arrived in Dallas and started going to his conferences. Of all the people I’ve mentioned thus far, Seldin by far had more influence on my career than anyone else. He was and is just spectacular.

WCR: How did it come about that you visited Dallas?

ME:I didn’t know what kind of career I wanted to pursue. Bob Narins encountered a number of problems with his academic career during my second year of fellowship. He never got tenure at Penn despite the fact that he ran Relman’s lab. He was supposed to go to Ohio State to become chief of nephrology but that didn’t work out. He wound up not having any job for a period of time. He had sold his place in Philadelphia and didn’t have a position. Although he went to UCLA eventually, I became very disillusioned with academic medicine during that year in the lab. I considered staying in academic nephrology at Penn or Temple, or possibly Yale, but I had little guidance. I also looked at several private clinical jobs.

At the annual meeting of the American Society of Nephrology held in Washington, DC, I met a medical school classmate, John Stokes, who was a renal fellow at Southwestern. He told me about a possible job in Dallas. (John is now chief of nephrology at Iowa.) He said, “You really ought to look into a group in Dallas run by Alan Hull.” I didn’t know Alan Hull but had heard of Southwestern’s chief of nephrology, Juha Kokko, so I sent him a letter. At the time I thought Juha was Japanese and was later surprised when I met this blond, blue-eyed Finn. Juha gave my letter to Alan Hull, who called me and asked me to come down to look at a job. At that time the Dallas nephrology group was pretty desperate to hire another nephrologist because the main nephrologist at Baylor, Charlie Austin, had committed suicide in 1975. Marty White had moved to BUMC, but there was an enormous volume of work and he needed help.

When Alan first invited me to Dallas I wasn’t that serious about coming. However, BUMC was very impressive and the job was clearly the best I had seen in terms of combining some academic involvement with clinical practice. I had looked at several other jobs, and none of them was even close. Rachel said that there was no way she was moving to Dallas. She offered to give me a list of 100 cities she would rather live in than Dallas. We didn’t know anything about Texas. The only thing we knew about Dallas was that Kennedy had been shot here. Alan then asked us both to return and we were royally wined and dined. The job seemed very good, and I promised Rachel that I’d stay only for a year or two. So we came!

Soon after I arrived, I first met Dr. Seldin (Figure 6). I had sort of developed a chip on my shoulder because in Dallas’s nephrology circles everyone talked about Seldin, Seldin, Seldin. I was tired of hearing this Seldin was so great. I had trained at pretty good places and I had interacted with pretty famous nephrologists—Drs. Relman, Epstein, Welt, Goldberg, Narins, Thier, and others. I figured the nephrologists in Dallas just hadn’t met anyone else who was really good. I started going to Dr. Seldin’s research conferences every Thursday afternoon at 5:00 PM, and they were really great. There was a lot of interaction, a lot of discussion of theories and models. There were many visiting nephrologists who presented data, and then Seldin would pick the data apart. It was clear that he was really special. He seemed to be a quantum leap beyond the other nephrologists I had worked with, not just in knowledge of nephrology but in knowledge of almost everything. I quickly got caught up in his very strong gravitational field.

Figure 6.

Michael and Rachel Emmett with Dr. Donald Seldin.

He knew who I was because of the articles I had published, and we interacted at his conferences. Soon he said, “I have to give a talk in Spain on phosphorus depletion. Why don’t we write a manuscript together about acid-base effects of phosphorus depletion?” I was honored that Dr. Seldin would ask me to do this. We wrote that manuscript together and I enjoyed it. That led to collaboration on a number of papers and chapters on various aspects of acid-base physiology, diuretics, edema, and related topics. I learned more from those experiences than anything else I had done in all my previous years of training in medicine and nephrology.

I’d write a first draft of a chapter on my own and give it to Dr. Seldin. Then I’d sit with him in his office for hours and hours, literally hundreds of hours. He would take my manuscript apart, not just scientifically, but would discuss sentence structure and point out the split infinitives and dangling participles. But, of course, mostly we discussed the science. He would critique the most minute details. It was an incredible experience to interact one on one with an intellectual giant for such an enormous amount of time. Of course, it was also painful because I’d have to rewrite and rewrite and rewrite. This was before the days of word processors. My secretaries, Lee Rhea Capote and then Ann Drew, typed these manuscripts on a noncorrecting IBM Selectric, and we went through thousands of pages. However, I learned so very much about acid-base and electrolyte physiology. Dr. Seldin was clearly the most important professional influence I have had during my career.

WCR: How did you enjoy the practice?

ME:I enjoyed taking care of patients, but I liked the scientific investigative aspects the most. I loved and still love the “fascinomas.” I really get excited when something strange or unusual comes in, acid-base, electrolyte, or really anything. I love to go to the library, look things up, and try to figure out what is wrong with patients and how best to treat them. I always seem to gravitate toward the odd and unusual disorders. I also became the local expert on anion gap and acid-base disorders, and people would call me with questions about unusual anion gaps or acidbase results. I especially loved to teach the medical students and the residents.

WCR: You came to Baylor in 1976?

ME:We left Philadelphia for Dallas on July 4, 1976. We flew over Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell. A huge crowd had gathered on the mall to celebrate the bicentennial Independence Day.

WCR: What was your initial position when you came to Dallas?

ME:I joined a group of nephrologists called Dallas Nephrology Associates (DNA) and based my practice primarily at BUMC. I was the seventh member of the nephrology group. Marty White was the chief of nephrology at BUMC, and I was the second nephrologist in the division. I also had responsibilities at other hospitals and spent a fair amount of time at Medical City, Presbyterian, and Doctors Hospitals. On weekends I covered the circuit. This was my role for my first 10 years in Dallas. I also volunteered to do a lot of teaching, attending on the general medicine service, proctoring students, and teaching residents who rotated on nephrology (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Dr. William Sutker presenting the best teacher award to Dr. Emmett in 1977.

WCR: What happened next?

ME:In 1986 I became the chief of nephrology when Marty White became the president of Dallas Nephrology Associates. By then John Fordtran had replaced Ralph Tompsett as chief of medicine. After Dr. Seldin, John Fordtran is the other physician who has had the most influence on my career. When John came to BUMC he brought his gastrointestinal (GI) physiology lab and research projects with him. Although Dr. Seldin and I wrote chapters and articles together, I wasn’t looking at any original research data. John Fordtran was very interested in GI electrolyte transport. There are many parallels between the physiology of the GI tract and the kidney. John had a research conference every week, which I attended. I enjoyed helping with the analysis and interpretation of data that his lab generated. We tried to correlate what was happening in the GI tract to what was happening in the kidneys.

WCR: This was in what year?

ME:In the early 1980s John and I began to collaborate on several interesting projects.

WCR: When did you take over the medical residents’ conference?

ME:I set up a number of conferences at Baylor because I so much enjoyed teaching. One conference was morning report. When I arrived at Baylor there was no morning report. I always thought that this conference was one of the strongest of my residency. Therefore, I set up morning report on my own in about1978. For a number of years I was the only person taking morning report.

WCR: Morning report was daily?

ME:It was held 3 times a week at 7:00 AM. It was really a fun conference and very well received.

WCR: You weren’t paid anything for it?

ME:No, I just loved to do it. Later other physicians heard about morning report and asked to get involved. They took report from time to time. I was also in charge of 2 nephrology conferences each month. In the early 1980s John asked me to take responsibility for the entire noon conference schedule. As my teaching role at Baylor expanded, John talked to the administration and asked them to subsidize me for all my work with the housestaff. As the hospital began to pay me, DNA freed up time for me to spend with the housestaff. Finally this evolved to the point that I was theoretically working half-time for BUMC and half-time for DNA. DNA was supposed to protect half my time for my academic interactions with the housestaff. This was purely theoretical and never really worked very well. Whenever the clinical service got busy, which was often, my partners would say, “Emmett’s got nothing to do” and pile on some extra work. That was very difficult. Much of my academic work had to be done on free weekends and nights.

In 1996, John decided to retire as chief, I think prematurely. He had always said he planned to retire when he turned 65. He wanted me to be the next chief. We had worked so closely in many venues. However, appropriately, the administration wanted to seek the very best person for the job and initiated a national search. Some very good people wanted the job and were interviewed. I was thrilled when I was picked.

WCR: You started in January 1996. You’ve enjoyed immensely being chairman of medicine at Baylor.

ME:Yes. It’s a great job.

WCR: Why is it such a great job?

ME:Because the major job demands I have are focused on creating and maintaining an excellent training program. There are other aspects of the job, of course—discipline issues, running a smooth department, care paths, quality initiatives, recruiting division leaders, and others—but my major job is my work with the housestaff. Recruiting residents, giving and organizing conferences, attending on the wards, taking morning report—these are the things I love, and they remain the main part of the job. Unlike other full-time chairs, I don’t have to deal very much with space or salary issues. Although they are part of my job, compared with other academic chairs of medicine, they are only a minute part.

WCR: You still have a small private practice?

ME:I still work about a half-day a week in private practice. I’ve toyed with the idea of giving that up, but I enjoy evaluating and following patients. People call me from time to time to see a friend or relative or some unusual interesting case. I have followed a few patients for many years, and they ask me to continue my practice. It’s something I do because I enjoy it. My financial remuneration for this practice is quite trivial.

WCR: Are you still occasionally seeing consults in the hospital?

ME:Rarely. I may be called in on a very difficult or unusual case. I tell my private patients that if they need admission I’ll see them socially but arrange for a colleague to see them and provide their daily care.

WCR: How have you been able to recruit such good residents, year in and year out?

ME:Baylor is such a special place. It combines many of the best attributes of private and academic programs. There are few institutions where the private attending staff is so well informed and so devoted and attuned to the educational needs of the residents. Also, we have a great medical school in Dallas, and many excellent Southwestern students decide to come to Baylor instead of Parkland. Our statewide reputation is very strong, and excellent students also come from the other Texas medical schools. Many students from Louisiana and Oklahoma also rank Baylor high on their lists. An occasional excellent student comes to us from California, New York, Mississippi, and other states. The Baylor residents are a very happy group, and when they go elsewhere for fellowships or practice, they spread the word.

WCR: What are your biggest problems or challenges as chairman of the Department of Medicine now at Baylor?

ME:Unlike most of my academic colleagues, I’m not consumed with financial issues, practice plans, managed care, and other administrative activities. These incredibly important issues are dealt with by the administration; therefore, I am protected. In recent years I have needed to spend more time recruiting division chiefs. The GI division will soon need a new chief, we still don’t have a chief of cardiology, and we now need to recruit a lead transplant nephrologist and hepatologist. These are major challenges. However, my major daily challenge is keeping our housestaff training program running smoothly.

WCR: Do you think with time the administration or the foundation will provide more money for additional full-time people in your department?

ME:I hope so and think they will. Although this will change the complexion of BUMC if it happens to a major degree, the pressures of making a living have become much greater for all internists. It’s impossible for them to devote a large amount of time to teaching on a purely voluntary basis. Doctors are frustrated that they do not have time to do some of the fun things in medicine like teaching medical students and residents. We are going to have to figure out some way to subsidize physicians to do those things in the future.

WCR: Mike, could you talk a bit about your family?

ME:I was married in 1969 to Rachel. As I discussed, we come from very similar backgrounds and are very comfortable with each other, in part because of that. Our first child was a daughter named Mira. She was born in New Haven in 1972. Daniel was born in Philadelphia in 1975, and Joshua in Dallas (at Baylor) in 1978 (Figure 8). All 3 kids went to public schools and graduated from Richardson High School. All 3 then went to The University of Texas in Austin. I would have loved it if all 3 kids had gone to medical school. Actually, I used to encourage Rachel to go to medical school. Medicine is still the most incredible profession. Despite the current problems with managed care and financial cutbacks, what profession could be more rewarding? However, Mira had no interest in the sciences or math. She went to Emory Law School, met her husband there, and is now an assistant district attorney in Clayton County, Georgia. She’s pregnant, and if all goes well our first grandchild will be born in September. Our second child, Daniel, did go to medical school and graduated from The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. He starts a medicine internship at Parkland in July. Our third child, Joshua, decided to pursue a computer/business career after graduating with a management information systems major. He and some buddies recently started an Internet company focusing on the music industry. It’s not the best time to be starting an Internet business, but he’s having a lot of fun working with this. He will be married in January 2002.

Figure 8.

Left to right: Daniel Emmett, Mira Emmett Katz, Bryan Katz, Michael Emmett, Rachel Emmett, Joshua Emmett. Photo: Jule Bovis.

WCR: Tell me about Rachel.

ME:She went to Temple University and was a math major. She then worked as a systems analyst in the 1970s using IBM 360s, paper tape drives, and all that. She first worked for the Federal Reserve Bank in Philadelphia. Her salary supported us and we were comfortable. After moving to New Haven for my internship, she got a job with New England Bell. After our first child was born, Rachel quit work and then didn’t try to work again until the kids were much older. She considered resuming a computer analyst career, but during her period away computers had changed markedly. It was apparent that she would need retraining, and she decided to pursue a graduate degree in computer science. The best program available in Dallas was at The University of Texas at Dallas, and the courses were given at night. She did spectacularly and got all As. However, the children and I hated it because when she was gone at night we had to cook our own meals. Our family grumbled so much she quit after 18 credits. I think she regrets having to do that. Then she got a fulltime job as a travel agent. She became a fantastic agent and worked for a number of years and enjoyed it. However, the travel industry has become increasingly frustrating because of many reductions and cutbacks by the airline and hotel industries. Rachel stopped working at that a couple of years ago and now does some volunteer work. She does hearing tests on high-risk newborn infants at Parkland and also tutors inner-city kids.

WCR: How do you spend your time when you’re at home or when you’re not committed professionally? Do you have hobbies, or what do you like to do outside of medicine?

ME:Growing up, I had very limited experiences. Golf, tennis, and skiing were things I saw only on television. They weren’t a part of my experience. I didn’t think “normal people” like me did those kinds of things. We played street stickball, sandlot baseball, and schoolyard basketball. In medical school I first tried tennis. I still have never tried to play golf, and I skied for the first time when I was about 35 (Figure 9). I never really became very good at any of these because I started them late in life and I’m not a gifted natural athlete. I enjoy tennis but play only every other month.

Figure 9.

Michael Emmett skiing.

Rachel and I love to travel, and we do travel quite a bit. We visit my relatives in Israel from time to time. We enjoy touring Europe, especially Italy and France. We enjoy a cruise occasionally. Rachel and I also love to read, and we read a wide variety of topics. I’m a slow reader but I usually read 3 or 4 different books simultaneously. Also, my drive to work takes 30 to 45 minutes, and I often listen to books on tape during the drive. Right now I am listening to a “Great Professor Course” on Einstein’s theory of relativity. It’s about 20 to 25 hours of tapes, and I’m about three quarters through it. I enjoyed learning more about black holes, relativity theory, and Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle. I’m finishing a biography of Osler and have started one of Ben Franklin. I also enjoy spy novels, mysteries, and scientifically oriented books.

WCR: What is your day-to-day life now as chairman of medicine? What time do you get up in the morning?

ME:I have always been very much a night person. I do my best work at night, probably after 10:00 PM. Therefore, if I had my choice I would work hard between 10:00 PM and 2:00 AM and then sleep late. Ideally, I would rise at 8:30 or 9:00 AM. Unfortunately, at Baylor I have a meeting almost every day at 6:00 or 7:00 AM. Therefore, I generally get up before 6:00 to be at work by 6:30 or 6:45 AM. After my morning meetings, I go to noon conference every day. I try never to miss those conferences. I’ll see a few private patients on Monday mornings and 2 or 3 transplant patients on Thursday afternoons. I meet with residents, do some writing, and prepare manuscripts or work on conferences on most days. I also have lots and lots of meetings. I’m not sure we accomplish so much with the meetings, but we sure do meet a lot.

WCR: What time do you leave the hospital generally during the week?

ME:I usually leave after 6:30 PM. The later I leave, the better the traffic. Very rarely I can get out early.

WCR: You are putting in a 12-hour day at Baylor.

ME:Most days.

WCR: What about when you get home at night? What are your evenings like?

ME:I always turn on the television as soon as I get home. Rachel hates this. I need background noise. Whether I’m reading or writing or working on a project, I like to have that background TV noise. It doesn’t make much difference what is on, usually some sporting event. Rachel always tries to turn the TV off, and then I turn it back on. I spend most of my evenings with medically related things: reading journals, getting lectures ready, working on manuscripts. I seem always to have a paper or chapter that is 3 or 4 months late that I must work on. Rachel and I are usually in bed after the 10:00 news. I have a stack of 5 or 6 books on my nightstand, and I pick one of them and read until I get tired and fall asleep about 11:00 or 11:30 PM. I have a dog who is a great friend. I just love to walk her through the park or around the block.

WCR: What about Saturdays and Sundays?

ME:We sleep a bit later. Some Saturdays I’ll play a little tennis. We go to the theater or symphony or a movie. In the summer we sit outside and read. We enjoy having friends over and going out to eat. On Sunday mornings we read the New York Times with breakfast and challenge each other with the Times crossword puzzle.

WCR: Do you go to synagogue anymore?

ME:Rachel and I talk about going to synagogue on a regular basis, but we never seem to get into that habit. In the Jewish religion when a parent dies, you are supposed to pray at the synagogue twice a day for a year. After each of my parents died, I attended afternoon prayers 3 or 4 days each week on my way home from work and on Saturday mornings. I did this because my parents would have expected this and it was therapeutic for me. We do go to synagogue on major religious holidays and an occasional Saturday morning. We do celebrate our Jewish traditions at home. On Friday nights Rachel usually cooks a special meal. She lights Sabbath candles and recites Sabbath prayers. It’s always more special when the kids are home. About once each month we get together with 4 or 5 other couples to celebrate the Friday night meal and service.

WCR: When you get home at night do you have a glass of wine?

ME:No. Rachel and I both enjoy a glass or two of wine when we go out to a special dinner, but we rarely have wine at home unless we have guests over for some special occasion.

WCR: Has Rachel grown to like Dallas?

ME:Yes. She really has. We now have a circle of friends that she’s very fond of, and our kids have their roots here. But I think Rachel is still mad at me for moving her away from Philadelphia and her family.

WCR: Are Rachel’s parents still alive? What does your sister do?

ME:Yes, Rachel’s parents are both alive. My sister is a housewife who raised 3 children. Her husband died some years ago.

WCR: When coming to Baylor in March 1993, I started going to the medical residency conferences that you organized. I was surprised to find that you gave a large percentage of the lectures in that conference. I was enormously impressed by your teaching abilities and your wide range of knowledge, not only in nephrology but also in metabolic diseases and in other areas. Your talk on aortic dissection was splendid. Do you think that your relatively slow progress in excelling scholastically (your hitting your peak in medical school) made you a better teacher than you would have become had learning always been easy for you?

ME:I love taking things apart, understanding how they fit together and their historical origins. That was definitely an acquired love because I wasn’t deeply interested in much of anything until I got to medical school. I enjoy explaining how and why various things work. The most fun for me is to take a seemingly complex subject and explain it lucidly to a group of students or physicians. Also I try to impart the enjoyment I derive from these analyses to those I’m teaching.

WCR: I’ve always thought of nephrology as the most academic medical subspecialty and internal medicine as the most academic of the major specialties. Do you think that’s fair?

ME:I think it was true of nephrology in the 1960s and 1970s. At that point, many great analytical and thoughtful physicians chose to study nephrology. Although the physiology was very complex and challenging, once understood it was in many respects “beautiful.” However, nephrology has changed quite a bit over the past 20 years. So much of current nephrology practice is related to dialysis and renal transplantation. Simultaneously, cardiology, oncology, endocrinology, and gastroenterology have become much more molecular biology oriented. The molecular and genetic basis of medicine is blurring the differences between those various fields. Many of the brightest students are now attracted to oncology and cardiology, not nephrology. Nephrology is now primarily directed at chronic care (dialysis and transplant) and not so much at physiology and electrolyte transport as in the 1960s and 1970s. I, for one, find this makes it a less interesting specialty.

WCR: Of the things you’ve done professionally, what are you most proud of at this point?

ME:It is clearly my efforts to continue and strengthen the academic legacy that Ralph Tompsett and John Fordtran established at BUMC.

WCR: Mike, is there anything that we haven’t discussed that you would like to talk about?

ME:We have covered an awful lot of territory. I was incredibly lucky to have stumbled onto BUMC and Dallas. Coming to BUMC was the most defining professional event in my life. Things would have turned out so very differently if I hadn’t come here. I’d probably be practicing nephrology somewhere in New Jersey, and I would have had a very different career. I think I would have been a successful practicing nephrologist, but I certainly wouldn’t have the academic success or great fun I’ve had here in Dallas.

WCR: Mike, thank you for providing so much information about yourself and for being so open.

ME:Thank you, Bill.