Abstract

Synaptic competition is a basic feature of developing neural connections. To shed light on its dependence on the activity pattern of competing inputs, we investigated in vivo rat motoneuronal firing during late embryonic and early neonatal life, when synapse elimination occurs in muscle. Electromyographic recordings with floating microelectrodes from tibialis anterior and soleus muscles revealed that action potentials of motoneurons belonging to the same pool have high temporal correlation. The very tight linkage, a few tens of milliseconds, corresponds to the narrow time windows of published paradigms of activity-dependent synaptic plasticity. A striking change occurs, however, soon after birth when motoneuronal firing switches to the adult uncorrelated type. The switch precedes the onset of synapse elimination, whose time course was determined with confocal microscopy. Interestingly, the soleus muscle, whose motoneurons switch to desynchronized activity later than those of the tibialis anterior muscle, also exhibits delayed synapse elimination. Our findings support a developmental model in which synchronous activity first favors polyneuronal innervation, whereas an asynchronous one subsequently promotes synapse elimination.

Synapse elimination is a widespread developmental process consisting in the initial formation of a redundant number of inputs on target cells, followed by a competitive interaction eventually leading to their withdrawal (1–5). At the neuromuscular junction, where synapse elimination was discovered (1), the embryonic polyneuronal innervation of muscle fibers is followed by rapid loss of all but one input during the first 2 weeks of neonatal life (2). Action potential activity is known to be important for elimination of neuromuscular (6, 7) and autonomic and cortical inputs (5, 8). However, the role of activity has been recently called into question for both the neuromuscular (9) and the visual system (10).

Recently, we demonstrated that synchronous activity evoked by electrical stimulation from competing neuromuscular inputs during synapse formation profoundly inhibits the elimination process (11). This represents direct evidence that the timing of action potentials in the neural inputs converging on the same myofibers affects their lifetime. Our finding strongly suggests the operation of Hebbian mechanisms (12) during neuromuscular synapse competition (see also ref. 13), in confirmation of the role of correlated activity in the development of binocular inputs on cortical neurons (5, 14). This finding further implies that elimination at least partially depends on asynchronous activity of motoneurons. However, knowledge of motoneuronal firing around the time of birth, particularly of the relative timing of individual spikes, has been lacking. Yet, this knowledge is crucial for understanding the mechanism of activity-dependent synaptic competition. To fill this gap, we investigated whether (i) asynchronous activity in competing inputs is present early enough in development to be a candidate factor for contributing to the elimination process and (ii) synchronous activity exists at earlier developmental times, embryonic or immediately postnatal, to possibly play a favorable or permissive role on the initial transient polyneuronal innervation.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Surgery.

All procedures obeyed Italian laws for protection of the experimental animals and carried out on fetal [embryonic day (E)17–E21] and postnatal [postnatal day (P)0–P31] Wistar rats. Rats P13 and onward are labeled here as “adults” because at this age mono-neuronal innervation has essentially been reached (2). Ether anesthesia was used for all surgery. A short skin incision exposed tibialis anterior (TA) and soleus muscles. Two pins were inserted, one under the patellar and the other under the Achilles tendon. At least 1 h after recovery, electromyographic (EMG) recordings were made with animal containment obtained with tapes across the body and the 2 pins inserted in a supporting plastic board. Recordings lasted 30–60 min, and the animal was then killed with excess ether. To record from embryos at E21, the mother was anesthetized with ether, the embryos were extracted from the uterus, and the remaining procedures were performed as above. Before E21, the mother was anesthetized and spinalized at mid-thoracic level; the embryos were left connected through the umbilical chord, and ether was then discontinued. However, no useful data were obtained before E21 because of poor signal-to-noise ratio.

Electrophysiology.

For EMG recordings, floating microelectrodes or thin wires were used, depending on age. The former, used at the earliest times, consisted of the short tips of glass micropipettes broken to ≈1.5-mm length, filled with 4 M NaCl, 1–5 MΩ in resistance. For differential recording, two such tips were inserted in the muscle, close to each other to maximize rejection of EMG activity of adjacent muscles, and connected to the amplifier (CyberAmp 320, Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) by 20-μm-diameter Ag-AgCl-coated copper wires. A reference electrode contacting the leg was grounded. In adult rats, the electrodes were two 25-μm-thick Teflon-insulated platinum wires (Advent, Oxford), glued together, cut obliquely to obtain slightly separated tips, and inserted parallel to the muscle longitudinal axis. Signal detection was further improved with hum pick-up suppression (Quest Scientific, Vancouver) and 200–800 Hz band pass filtering. Amplified spikes were digitized at 50 KHz and acquired on a Pentium PC with SPIKE 2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, U.K.).

Crosscorrelation Analysis of EMG Unit Pairs.

EMG unit signals vary considerably in amplitude in newborn rats, unlike in the adult, as analyzed in Results. Recognition was based on reasonable stability of shape and amplitude: constancy of number (usually 2–3) and sequence (polarity) of phases and variation not larger than ±40% in the overall duration and amplitude of the individual phases. The largest values of this variation correspond to signals occasionally accepted when other criteria pointed to the same unit, such as regularity of firing rate. In >85% of all unit signal occurrences encoded in the present study, variation of amplitude and duration did not exceed ±20%. Encoding, much easier when only a few units were active, was first made automatically by SPIKE 2, then corrected for mistakes or omissions by visual inspection of each potential. This was required up to ≈P10, but rarely later, the main reasons being amplitude variation and baseline fluctuations remaining after filtration. In addition, the tight temporal correlation found by us in newborn rats defeated the automatic detection of the components of a unit pair when they overlapped, thus creating complex patterns. The two units were nonetheless recognized and coded manually, if a similar pattern was reproduced using a module that summates at various delays their templates, obtained by averaging their waveforms when firing in isolation (Fig. 1A). This analysis is reliable only when the two waveforms are clearly different, a prerequisite of the entire study. Fig. 1B shows another case in which two signals often fired almost simultaneously, with little change in the time separation of their onsets; in this case, it was sufficient to compare the average of a number of these superimposed waveforms with the pattern obtained by summating the templates of the individual waveforms, at just one appropriate delay. Cross correlograms between pairs of unit potentials were obtained by measuring the intervals between each occurrence of one unit taken as reference (time 0) and all occurrences of the other unit, preceding or following within a ±150-ms window, over a mean period of 2′ ± 34", n = 35. Bin width was 5 ms. A higher probability of a given interval(s) appears as a peak over the baseline, i.e., the chance level, a peak near time 0 indicating a trend toward synchrony. Presence and duration of the peak was based on the curve of cumulative sum (see ref. 15) and baseline level given by the mean number of counts outside the peak. To measure the strength of the correlation, we used the correlation index k′ (15) that is the ratio between total counts within the peak and those expected in the same period due to chance. A correlation was considered significant when peak area exceeded the underlying baseline area by more than three standard deviations.

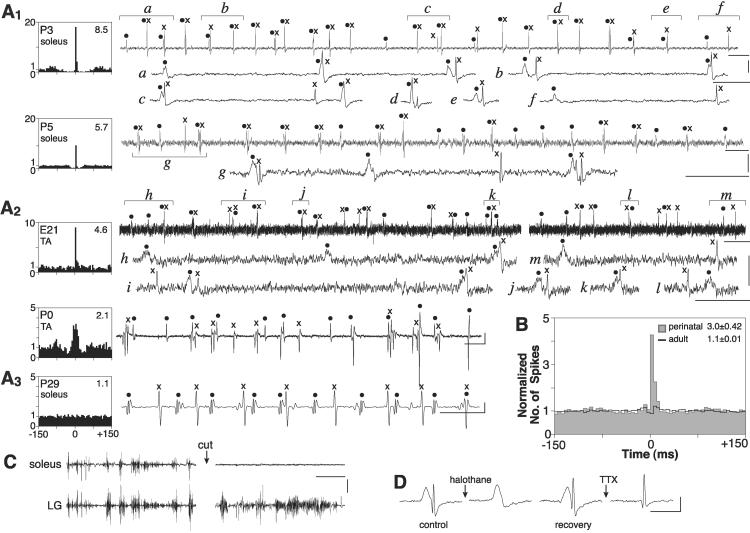

Figure 1.

Procedure for identification of EMG units, when firing simultaneously. (A1–3) Two units from a TA muscle at P0 (k′ 1.4), sometimes superimposed (examples of raw data in A3), as indicated by artificial superposition at various delays (A2) of the averaged individual waveforms (10 each) obtained when firing in isolation (A1). (B) Same approach, but at one delay only, for the 2 units shown in Fig. 2A2 (TA/E21). All waveforms are averages (14–30), a and b of the units firing in isolation, c of the raw data of superimposed waveforms, whereas d is the artificial superposition of waveforms a and b at the appropriate delay. Calibrations: time, 10 ms; voltage, 100 μV in A and 30 μV in B.

Analysis of Multiunit Recordings.

When motoneuronal activity increases, EMG records become complex and single units can no longer be resolved. To still be able to investigate the relative timing of spikes, we determined for each recorded muscle the coefficient of variation (CV) of interspike intervals, obtained by feeding its EMG data through the following custom-written modules, based on AXOGRAPH 4.6 software (Axon Instruments): highpass filtering (40 Hz); detection of spikes crossing threshold (10× the SD of noise) in the polarity exhibiting only one phase; selection of all 600-ms-long sections with sustained activity (>40–90 Hz on average, depending on age) to ensure a minimum of 3 motor units coactive; and calculation of the CV of interspike intervals for each section.

All CV values from the same muscle were plotted against the average firing frequency of their corresponding sections. Although dealing with multiunit recordings, spikes too close to each other cannot be resolved as two separate events by an automatic module, thus introducing a minimum interval between consecutive detected spikes (1/fmax) that is equivalent to the presence of a refractory period in the spike train generated by a single neuron. This introduces an artifactual linear reduction in the CV as spike frequency (f) increases, such that CV(f) = (1 − f/fmax)CV (16). At maximum theoretical frequency fmax, spike events detected by the module are spaced by identical intervals (1/fmax) and CV = 0. fmax was estimated for each recording from its power spectrum. A straight line, pivoting around the point where f = fmax and CV = 0, was fitted to the data, and its height at f = 0 was taken as representative of the theoretical CV value of the underlying spike activity.

Confocal Fluorescence Microscopy.

Muscles were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and incubated with anti-neurofilament (1:80, Sigma), anti-synaptophysin (1:100, Sigma) Abs, and rhodamine-α bungarotoxin (10 μg/ml, Molecular Probes) to stain axons and acetylcholine receptors. Primary Abs were visualized with Alexa 488-labeled secondary Abs (1:200, green, Molecular Probes). Muscles were observed in whole mount with a Zeiss laser-scanning confocal microscope.

Statistics.

Results are expressed as mean ± SE, except where otherwise indicated. Significant differences are based on Student's t test, P values <0.05 being considered significant.

Results

To assess whether activity changed from synchronous to asynchronous during neuromuscular synapse formation, we recorded motoneuronal firing at various developmental stages. To assess the temporal relationship between asynchronous activity and synapse elimination, it was necessary to start recording not later than the first few postnatal days, because elimination is virtually complete around P15 (2). To detect an earlier phase of synchronous activity, one should ideally start recording in the embryo soon after the onset of synaptogenesis. In practice this is impossible, but data obtained at perinatal times should still be highly informative.

Motoneuronal spike activity is best obtained recording the motor unit signal from muscle. The small EMG potentials of embryos and newborn rats, however, require optimal detection conditions. Electrodes with small tip diameters are necessary, but no rigid connection to a micromanipulator is permitted because some degree of movement of the limb must be allowed. In embryos and neonates, we resorted to floating microelectrodes. The muscle surface was exposed under anesthesia, whereas the insertion of the microelectrode tips was made after complete recovery. In older animals (P10–31), thin wires were inserted into the muscle during anesthesia and left in place until recording, again after the anesthesia had worn off. An important requisite is that the EMG activity is only generated by the recorded muscle. This was ensured by differential recording and ascertained by cutting the muscle nerve at the end of the experiment. Usually, this abolished all activity recorded in that muscle, whereas it did not affect that of adjacent muscles simultaneously recorded in part of the experiments (Fig. 2C). Only rarely were low amplitude signals, below threshold for spike analysis, still detectable in the denervated muscle, when studying the higher levels of activity. Further evidence for the absence of cross talk is the alternate electrical silence observed when simultaneously recording consecutive cycles of activity from the antagonist's soleus and TA (Fig. 3A).

Figure 2.

EMG recordings of unit potentials from soleus and TA muscles in newborn rats. (A1–3) Synchronous firing is present perinatally in motoneurons innervating the same muscle and switches to asynchronous in adults. (Right) Records from various muscles, each with a unit pair encoded. (Left) Corresponding cross correlograms (parameters as in B) based on all of the potentials unequivocally identifiable of a given pair. (A1) Two neonatal soleus muscles, each with a highly correlated pair of units, displayed as a continuous record as well as selected expanded parts, as indicated. (A2) Two TA muscles, one embryonic (E21) with a highly correlated pair, one neonatal (P0) with a moderately correlated one. (A3) One adult muscle. (B) Averaged correlograms based on all identifiable units at perinatal (gray area, 30 pairs, 17 muscles; soleus E21–P5, TA E21–P2) and adult age (black line, 47 pairs, 12 soleus and TA muscles, P13–30). All correlograms: bin width, 5 ms; ordinate, no. of spikes relative to baseline; correlation index k′ shown in the right upper corner. (C) Soleus nerve cut abolishes EMG activity recorded in soleus but not in lateral gastrocnemius (LG) muscle. (D) Alternative isolation of the 2 units shown in A1/P5 (see text); each waveform is the mean of 12–30 records. Calibrations: time, 25 ms, except 50 ms for upper trace in A1/P5, A2/P0, and expanded traces in A2/E21, 100 ms for upper trace in A1/P3, 200 ms for upper trace in A2/E21, 1 s for C, 10 ms for D; voltage, 100 μV, except 200 μV for A2/P0, 1 mV for C, and 50 μV for D.

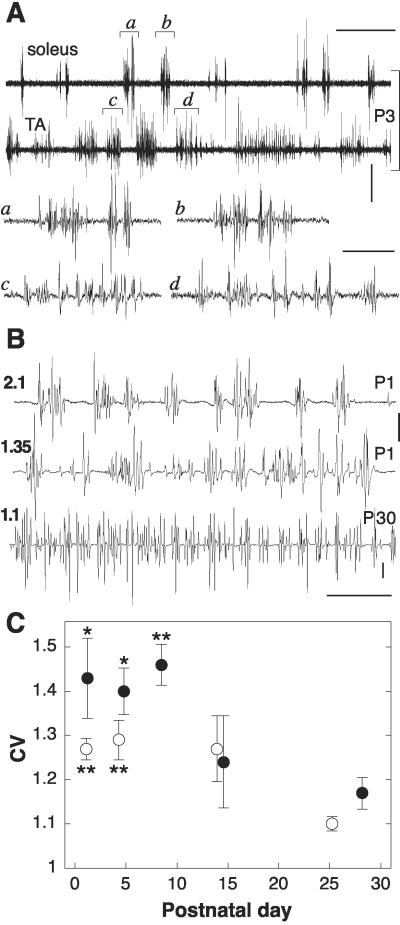

Figure 3.

In soleus muscle, firing of multiple motor units tends to occur in clusters at perinatal but not adult ages. A similar but less pronounced trend is also present in TA muscles. (A) Examples from ipsilateral TA and soleus muscles recorded simultaneously at P3. Expanded traces in a through d. (B) Examples of various degrees of grouping and corresponding CV of interspike intervals (number to the left) in soleus muscles: early developmental (P1, two examples) vs. adult condition (P30). (C) Time course of CV in soleus (●) and TA (○) muscles from P0 to P30. Each data point is the mean ± SE of several muscles, as specified below. The points for soleus and TA muscles before P10 are all significantly higher (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01) than the corresponding points at the adult age. Furthermore, the values for soleus muscles before P10 are significantly higher (P < 0.005) than those for TA muscles relative to the same time period. Postnatal day/number of muscles: soleus P0–2/10, P3–6/16, P7–10/6, P13–15/4, P18–31/5; TA P0–2/32, P3–6/24, P13–15/6, P18–31/5. Calibrations: time, 100 ms, except 1 s for upper two traces in A; voltage, 100 μV, except 500 μV for upper two traces in B.

Two levels of EMG activity were examined while the animal performed flexion and extension hind-limb movements (see example in Fig. 3A) or placement contractions, either spontaneously or more frequently after tactile stimulation of the foot: (i) an interference pattern that is a high level of activity in which many motor units are coactivated and (ii) the repetitive firing of a few motor units, so that each unit potential can be identified. Only the latter allows cross correlation studies of the timing of spikes of different units. The two types of analysis were mostly made on different phases of the same movement.

The recording quality significantly improved over the first 3–4 postnatal weeks, regarding signal-to-noise ratio and stability of shape and amplitude of unit potentials. The variability of neonatal unit potentials, already described (17, 18), has multiple causes: first, the effects of movement, which we minimized with floating electrodes; second, intermittent failure of neuromuscular transmission at terminals undergoing elimination; and third, intermittent failure of spike invasion of an axon branch (motor unit fragmentation), either due to developmental immaturity or to impending axonal withdrawal in the process of synapse elimination. Other factors depend on multiple innervation of myofibers so that when two motoneurons innervating the same fiber fire closely in time, facilitation or occlusion may occur. Finally, small unit signals may intermittently summate with those selected for encoding, contributing to their variability. These problems sometimes make the encoding of motor unit signals difficult, and some mistakes are unavoidable; nevertheless, they are more likely to deteriorate rather than improve an existing correlation.

Intermittent branch point failure would not create an interpretation problem when only one such branch existed within a motor unit because it could not mimic the case of two apparently independent motor unit signals that, at times, fire in close temporal association. This would only occur in the more complex hypothesis of at least two intermittently and independently failing branches within the same unit. The possibility of being misled by this unlikely case, as well as by other sources of error, was avoided by selecting as pairs for cross correlation analysis only signals possessing all of the following features: (i) clearly different shapes, so that they can always be recognized even when firing in synchrony; (ii) a significant number of instances in which each waveform is present in isolation; (iii) acceptance of a waveform as indicative of each of the two units only if relatively simple in shape, i.e., with a maximum of three phases; and (iv) when firing in close temporal association, a significantly variable delay time (not fixed) between the two signals. Further stringent criteria for discarding the possibility of a systematic bias of our data and their interpretation by the possibilities discussed above are represented by (i) our observation, to be described later in detail, that when many motoneurons are simultaneously active they tend to fire their spikes in synchrony forming clusters (Fig. 3), and (ii) the successful separation of two closely time-associated signals. After several attempts, we obtained clear evidence for separation, as each of the two signals could be observed in isolation, by using either the anesthetic and gap junction blocker halothane or the conduction blocker TTX (both Sigma), as shown in Fig. 2D. This unit pair is the same soleus P5 pair shown in Fig. 2A, where the frequent synchronous firing of the two waveforms is clearly apparent. The control record in Fig. 2D is an average of several such closely associated signals. A few minutes after brief inhalation of halothane, the fast signal disappears, to reappear after ≈45 min of air breathing. Application at this point of TTX in saline (6.8 μg/ml) on the sciatic nerve is first followed by disappearance of both signals, then upon washing by the reappearance of the fast signal alone.

Despite these difficulties, already at early times in development we obtained signals of sufficient quality for single unit encoding. One basic question we asked was whether a correlation exists between the time of firing of different units in the same record. In newborn rats (P0–5), as well as in the E21 embryos from which we could successfully record unit potentials, the answer was positive. This was true for both TA and soleus muscles, but it was more pronounced and lasted longer in the latter, as will be described in detail later. Thus, the cross correlogram plotted relative to each pair of units often showed a peak near time 0. On the other hand, EMG unit pairs recorded from muscles of slightly older rats (referred to as adults) essentially exhibited no correlation. Presence or absence of correlation was a stable feature of a unit pair. Various examples are shown in Fig. 2A. To obtain a quantitative assessment of this striking difference, we averaged all of the correlograms of TA and soleus muscles of perinatal rats (soleus E21–P5, TA E21–P2, 30 pairs) and compared the resulting plot with that of a similar average from adult rats (P13–30, 47 pairs). Fig. 2B shows that the peak of intervals present perinatally near time 0 is absent in the adults. The strength of the correlation in the embryos and newborn group is indicated by the correlation index k′, which had a mean value of 3.0 ± 0.42, to be contrasted with a value close to unity in the adults (1.1 ± 0.01). Fig. 2B also shows that the temporal linkage among motor units was on average rather tight, within the range of 25 ms, the most frequent interval being 5 ms.

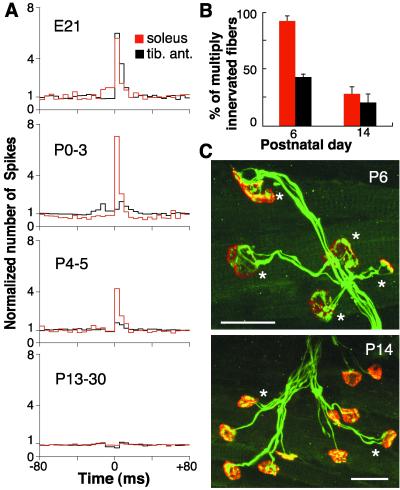

The degree of correlation already started to decline at early times. Thus, at E21, 100% of unit pairs were significantly correlated (correlated/total, 5/5); at P0–3, 71% (12/17); at P4–5, 61% (15/24); and in the adults only 11% (5/47). In this respect, TA unit pairs became uncorrelated earlier than soleus ones. The evolution over time of the correlograms of the two muscle types is shown in Fig. 4A, which indicates that a few days after birth, TA units are no longer correlated, whereas many soleus ones still are. This opened the question of whether a similar time differential existed between TA and soleus muscle in the process of synapse elimination. Measurements based on confocal fluorescence microscopy (see examples in Fig. 4C) confirmed this, as shown in Fig. 4B that summarizes the percentages of muscle fibers innervated by more than one axon in the two muscles at P6 and P14. Although at P14 they both have low percentages of polyinnervation (elimination almost complete), at P6 the soleus percentage is much higher than that of TA, indicating a delayed elimination in soleus.

Figure 4.

The postnatal loss of synchrony of motor unit firing occurs sooner in TA than in soleus muscles. A similar temporal sequence also characterizes the process of synapse elimination in the two muscles. (A) Averaged correlograms of multiple muscles as in Fig. 2B, but grouped according to type and animal age (soleus red, TA black line). No. of soleus motor units/no. of unit pairs/no. of muscles/age: 4/2/2/E21, 5/4/2/P0–3, 14/10/6/P4–5, 31/32/7/P13–30. Same for TA muscles: 6/3/3/E21, 15/13/6/P0–3, 14/14/4/P4–5, 16/15/5/P13–30. Pooling all data between P0 and P5, the correlation index k′ is significantly higher for soleus than TA unit pairs (3.7 ± 0.76 and 1.5 ± 0.14, respectively, P < 0.02). (B) Percentage of muscle fibers innervated by more than one axon at P6 and P14, in soleus and TA muscles. Counts are made at neuromuscular junctions visualized with confocal fluorescence microscopy: acetylcholine receptors with rhodamine-α bungarotoxin (red) and axons and motor terminals with anti-neurofilament and anti-synaptophysin Abs (green), respectively. No. of muscles/no. of fibers/age: soleus 3/657/P6, 4/888/P14; TA 4/801/P6, 4/717/P14. (C) Examples of confocal images of soleus neuromuscular junctions at the two different stages of maturation. *, Endplates innervated by more than one axon. Note prevalence of monoinnervated junctions at P14. Calibration: 25 μm.

Regarding the general features of EMG activity in newborn rats, spike frequency increased with age in both soleus and TA units. Soleus ranged from 13 ± 1.1 spikes s−1 (E21–P3, n = 9) to 28 ± 1.5 (P14–30, n = 29) and TA from 13 ± 0.6 (E21–P3, n = 20) to 44 ± 2.0 (P13–23, n = 16). These values correspond to the low range of activity, the data being the same as that used for the cross correlation analysis, which required the low range of spike frequency to facilitate encoding of units. Another clear-cut developmental change affected discharge mode and duration in the two muscles. After ≈P15, TA units are phasic, intermittently firing during locomotion, whereas soleus ones are, in addition, tonically active during standing, a well known pattern (18). In newborn rats, the reverse situation was true with short bursts of activity of soleus units, interposed between long-lasting discharges of TA, confirming and extending previous reports (17, 18). Thus, burst duration in soleus increased from 0.9 ± 0.11 s (P0–4) to 5.3 ± 1.25 (P14–30, P < 0.002), whereas that of TA decreased from 1.7 ± 0.13 (P0–4) to 1.1 ± 0.09 (P13–31, P < 0.01; 31–166 epochs examined; criteria: interval between bursts >200 ms; burst duration >30 ms; activity at P0–4 >10 Hz in both muscles, at P13–31 >20 Hz in soleus and >40 Hz in TA).

Thus far, we have shown that a perinatal trend toward synchrony can be detected at lower activity levels. If this holds true also when many motoneurons are recruited, one would expect the spikes to be grouped in clusters regularly spaced by pauses, corresponding to the period of single unit firing. Furthermore, no grouping should be present in the adults, in which motoneurons appear desynchronized. The validity of both predictions is already apparent by careful inspection of records (Fig. 3 A and B), as noted (18). However, to obtain an objective assessment, we developed specific software through which we fed all of the recordings to determine the CV of interspike intervals as a function of age. Whereas firing with random independent intervals (Poisson process) yields a CV value of 1, the more “bursty” the firing, the higher the CV will become with respect to unity (16). The results are shown in Fig. 3C. For soleus muscles, CV was consistently higher than 1 in neonates, whereas it decreased to a level significantly closer to 1 in the adults, indicating a transient spike grouping soon after birth. In TA muscles, the situation was similar, albeit less pronounced, because their CVs were at birth significantly lower than in soleus muscles, although significantly higher than in adult TA. The early difference between TA and soleus is in good match to the earlier desynchronization described above for the EMG unit pairs of the former muscle. The ratio of rate of spike clusters to that of spikes in single unit discharges was 1.4 ± 0.13 (nine soleus and seven TA muscles), indicating a higher frequency of the former, as would be expected, considering that clustering is observed when the level of excitation of the motoneuronal pool is higher than that required for unequivocal coding of unit potentials.

Discussion

Our main finding is that EMG single unit recordings performed in vivo at the earliest possible time during development reveal a clear trend of hindlimb motoneurons (TA and soleus) innervating the same muscle to fire together closely in time. A desynchronization process follows, starting first in TA and then in soleus units and being essentially completed by ≈P15. The analysis was made during flexion and extension movements of the foot at different levels of activity, within the same contraction, to permit both (i) cross correlation of clearly identified single units, which requires low activity levels, to unequivocally establish the existence of a time linkage and (ii) analysis of the discharge pattern of many motoneurons simultaneously, when higher levels of activity prevail. The first study detected the existence at perinatal ages of a narrow window of ≈25 ms for the firing of different units, 5 ms being the most frequent interval. The second analysis accordingly indicated that the correlated simultaneous firing of many motoneurons results in groups of spikes separated by pauses. The importance of the last finding is 2-fold: (i) it shows that the spike correlation holds true at different levels of excitation of the motoneuronal pool, and (ii) it helps eliminate, together with other stringent criteria (experiments with blocking agents, Fig. 2D), the objection that what seems like synchrony between partners of a pair is really fragmentation within the same EMG unit (see Results).

The switch from synchronous to asynchronous activity occurs during the period of synapse elimination and is largely complete when the innervation reaches the adult mononeuronal stage. These findings must be evaluated in the light of our recent demonstration that exogenously evoked synchronous activation of multiple inputs on myofibers inhibits synapse elimination, thus indicating that physiological asynchronous activity plays a principal role in this process (11). The developmental motoneuronal de-synchronization found here represents another important piece of evidence in support of this contention. Furthermore, because synapse elimination starts sooner in TA than in soleus muscles, the earlier loss of spike correlation in TA units represents additional strong support for the existence of a causal relationship between the two events. A corollary of this is that the early synchronous activity favors the establishment of multiple inputs on each target myofiber because it prevents the competitive interactions between converging inputs.

An important precedent to our findings is that gap junction-mediated electrotonic coupling is found between motoneurons in the isolated spinal cord of newborn rats (19, 20). Furthermore, a gap junction-mediated synchronization of TTX-resistant membrane potential oscillations of motoneurons has been demonstrated in the same preparation (21). Our findings would suggest that the small junctional depolarizing potentials observed in neonatal motoneurons are sufficient to induce a temporal linkage between spikes of cells of the same motor pool. Future studies will have to critically test whether gap junctions are indeed the basis of the tight motoneuronal linkage demonstrated here in the developing cord. Our preliminary tests of the effects on correlated activity of gap junction blocker halothane have been inconclusive, essentially showing a global reduction of activity through an anesthetic-like effect. Alternatively, premotoneuronal mechanisms of motoneuron synchronization should also be considered.

In a recent study on newborn mice, conclusions similar to ours have been reached based on the observation of a transient time correlation in motoneuronal firing (22). The peaks of cross correlograms, however, differ from ours in having a much broader (100 times or more) temporal base. There are two possible reasons for this difference. One would be a loose correlation between spikes in conjunction with a very low firing frequency. A difference in firing frequency of neonatal soleus motor units does exist between the two studies; theirs is in fact lower than ours, ≈0.5 and ≈10 Hz, respectively. Our values, obtained during foot extension movements, agree well with the rat literature (17, 18); furthermore, we are not aware that much smaller values are generally typical of mice. Rather, it seems likely that the low frequencies reported in the mouse study resulted from having made the EMG recordings during standing, a condition of much lower, postural activity. This in turn could make it unlikely for motoneurons to fire their spikes in tight correlation because of the low degree of excitation of their pool. The second explanation would be that in their study, a correlation existed between trains of spikes, rather than between the spikes themselves as in our study; onset, frequency modulation, and cessation of firing are correlated so that motoneurons discharge in phase. Regarding this possibility, i.e., intertrain correlation, its transient character during development would be surprising because the firing of homonymous motoneurons tends to occur simultaneously at all ages. Thus, the adult loss of this type of correlation would only be apparent, as it could not be attributed to the fact that motoneurons cease to fire in phase. It could, however, be explained if their bursts became longer than the time base of the correlation analysis. It is indeed well known that soleus motoneurons fire tonically in the adult (18, 23). Moreover, this and other rat studies (17, 18) show that at birth their firing is phasic in character and changes to the long-lasting mode only after the first few days of neonatal life. In conclusion, however, even if the transient correlation in mice were entirely because of true spike correlation, it seems unlikely that such a loose correlation (correlogram peaks in excess of 2 s on average) would have effects on synapse competition.

Short delays similar to ours characterize heterosynaptic suppression, a phenomenon observed in Xenopus cultured myofibers co-innervated by two neurons. This consists in the immediate functional suppression of the synapse made by one neuron if it is tetanized not in synchrony with the other but only after a short delay time (24). The similarity in the timing of spike correlation in our study and the time window for heterosynaptic suppression is of considerable interest, with the reservation that heterosynaptic suppression might prove to be a different phenomenon if no elimination of the functionally suppressed synapse takes place after the necessary time has elapsed. Nevertheless, similar short delay times characterize a number of different paradigms, pertaining not to development but to activity-dependent synaptic plasticity (see ref. 24 for review).

The narrow time window, within which neonatal motoneurons tend to fire their spikes, deserves a final comment. The fading character of the correlation probably prevented us from detecting the shortest value that this time can exhibit. Its assessment, however, is important to further our understanding of the mechanisms underlying synapse elimination. Although it may be difficult to record motoneuronal activity when synapses first form in embryos, asynchronous electrical stimulation of competing inputs during adult muscle reinnervation (11) should allow us to gain information on this critical time window.

Acknowledgments

The financial support of Telethon-Italy Grant 1002 is gratefully acknowledged.

Abbreviations

- CV

coefficient of variation

- EMG

electromyographic

- TA

tibialis anterior

- En

embryonic day n

- Pn

postnatal day n

References

- 1.Redfern P. J Physiol (London) 1970;209:701–709. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown M C, Jansen J K S, van Essen D C. J Physiol (London) 1976;261:387–424. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lichtman J W, Colman H. Neuron. 2000;25:269–278. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80893-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mariani J, Changeux J P. J Neurosci. 1981;1:696–702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-07-00696.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katz L C, Shatz C J. Science. 1996;274:1133–1138. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson W J, Kuffler D P, Jansen J K S. Neuroscience. 1979;4:271–281. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(79)90088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson W J. Nature (London) 1983;302:614–616. doi: 10.1038/302614a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stryker M P, Harris W. J Neurosci. 1986;6:2117–2133. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-08-02117.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costanzo E M, Barry J A, Ribchester R R. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:694–700. doi: 10.1038/76649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crowley J C, Katz L C. Science. 2000;290:1321–1324. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5495.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Busetto G, Buffelli M, Tognana E, Bellico F, Cangiano A. J Neurosci. 2000;20:685–695. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-02-00685.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hebb D. The Organization of Behavior. New York: Wiley; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balice-Gordon R J, Lichtman J W. Nature (London) 1994;372:519–524. doi: 10.1038/372519a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hubel D H, Wiesel T N. J Neurophysiol. 1965;28:1041–1059. doi: 10.1152/jn.1965.28.6.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellaway P H, Murthy K S K. Q J Exp Physiol. 1985;70:219–232. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1985.sp002905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gabbiani F, Koch C. In: Methods in Neuronal Modeling. 2nd Ed. Segev I, Koch C, editors. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1998. pp. 313–360. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Navarrete R, Vrbová G. Dev Brain Res. 1983;8:11–19. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(94)00198-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Westerga J, Gramsbergen A. Dev Brain Res. 1994;80:233–243. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(94)90108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walton K D, Navarrete R. J Physiol (London) 1991;433:283–305. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang Q, Gonzalez M, Pinter M J, Balice-Gordon R J. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10813–10828. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-24-10813.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tresch M C, Kiehn O. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:593–599. doi: 10.1038/75768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Personius K E, Balice-Gordon R J. Neuron. 2001;31:395–408. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00369-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hennig R, Lømo T. Nature (London) 1985;314:164–166. doi: 10.1038/314164a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bi G-q, Poo M-m. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:139–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]