Abstract

The enormous improvement of molecular typing techniques for epidemiological and clinical studies has not always been matched by an equivalent effort in applying optimal criteria for the analysis of both phenotypic and molecular data. In spite of the availability of a large collection of statistical and phylogenetic methods, the vast majority of commercial packages are limited by using only the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean algorithm to construct trees and by considering electrophoretic pattern only as migration distances. The latter method has serious drawbacks when different runs (separate gels) of the same molecular analysis are to be compared. This work presents a multicenter comparison of three different systems of banding pattern analysis on random amplified polymorphic DNA, (GACA)4, and contour-clamped homogeneous electric field patterns from strains of Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans isolated in different clinical and geographical situations and a standard Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain employed as an outgroup. The systems considered were evaluated for their actual ability to(i) recognize identities, (ii) define complete differences (i.e., the ability to place S. cerevisiae out of the C. neoformans cluster), and (iii) estimate the extent of similarity among different strains. The ability to cluster strains according to the patient from which they were isolated was also evaluated. The results indicate that different algorithms do indeed produce divergent trees, both in overall topology and in clustering of individual strains, thus suggesting that care must be taken by individual investigators to use the most appropriate procedure and by the scientific community in defining a consensus system.

In recent years, epidemiologists have used a number of molecular tools to characterize isolates of medically important species (2, 7, 10, 12, 13) and to find relationships between molecular markers and different clinical features. The latter field of study consists of examining several genotypical features, normally DNA banding patterns, on the assumption that organisms similar for many parameters are very likely to be similar also in infective ability. In this context, correct processing and extensive analyses of the banding patterns obtained from the electrophoresis of informative macromolecules are instrumental for an effective understanding of the actual differences among isolates. The majority of the most-popular commercial software packages, however, offers very few combinations of statistical analyses, thus precluding a critical interpretation of typing data from both a statistical and phylogenetic viewpoint.

In this work a comparison of three systems for the analysis of typing data is presented. These consist of two commercial packages, specifically designed to interpret data from electrophoretic banding patterns, and one system under development at the Industrial Yeasts Collection of the Dipartimento di Biologia Vegetale di Perugia (DBVPG). These procedures have been employed separately in a multicenter comparison carried out on the same digitalized pictures obtained with three of the most widely used molecular procedures (random amplified polymorphic DNA [RAPD] analysis, contour-clamped homogeneous electric field [CHEF] analysis, and [GACA]4 analysis) carried out on 12 strains of Cryptococcus neoformans and one reference strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The first aim of this work is to determine whether different analytical systems produce dendrograms with significantly diverse topologies. The second aim is to ascertain how these systems estimate the distances among the strains under study and whether they recognize their geographic and clinical source of isolation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and DNA extraction.

The strains employed (Table 1) were obtained from the Industrial Yeasts Collection of the DBVPG (http://www.agr.unipg.it/dbvpg/home.html). The origin of isolation of the clinical strains is reported as by the prefixes “MI” and “PG” for the strains obtained from the Dipartimento di Medicina Sperimentale e Scienze Biochimiche and from the from the Istituto di Igiene and Medicina Preventiva of the University of Milan, respectively. The five strains from Perugia, hereinafter referred to as the PG strains, include two strains (PG 1525 and PG 1526) isolated from the same patient on the same occasion from blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (1) and three unrelated strains. The six strains from Milan, hereinafter referred to as the MI strains, derive from two patients as indicated in Table 1. The four strains from patient G were chosen because they were isolated in the same period, two from blood and two from CSF, in order to include in the study two pairs of clinically related isolates.

TABLE 1.

Strains employed in this study

| Species | Straina | Serotype | Isolation notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae | DBVPG 6820 | Outgroup | |

| C. neoformans | CBS 6995 | D | Type strain |

| C. neoformans | PG 1525 | A | Patient A (blood) |

| C. neoformans | PG 1526 | D | Patient A (CSF) |

| C. neoformans | PG 1934 | D | Patient B (skin) |

| C. neoformans | PG1883 | AD | Patient C (CSF) |

| C. neoformans | PG 1988 | D | Patient D (CSF) |

| C. neoformans | MI 15 | A | Patient E |

| C. neoformans | MI 17 | D | Patient F |

| C. neoformans | MI 1956A | D | Patient G (blood) |

| C. neoformans | MI 1956F | D | Patient G (blood) |

| C. neoformans | MI 1988A | D | Patient G (CSF) |

| C. neoformans | MI 1988C | D | Patient G (CSF) |

Strains with the prefixes “PG” and “MI” are from the hospitals of Perugia and Milan, respectively. CBS 6995 is a reference strain obtained from the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, The Netherlands. S. cerevisiae DBVPG 6820 is a reference strain (YNN 295) employed in this study as a general outgroup.

Cells were grown in 500-ml bottles containing 50 ml of YEPD (1% yeast extract, 1% peptone, and 2% dextrose) at 25°C with shaking at 150 rpm for 18 h. The serotypes of C. neoformans strains were determined at the University of Milan by slide agglutination with Crypto Check (Iatron Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan).

DNA for RAPD experiments was extracted and purified according to an existing method (3); chromosomal-grade DNA was extracted according to the procedure of Cardinali et al. (5). In both methods, the only modification was to double the amount of biomass employed in order compensate for the presence of the large capsule typical of C. neoformans. Extraction of genomic DNA for (GACA)4 analysis was also performed as previously described (13).

RAPD analyses.

Primers ZP19 (AAGAGCCCGT) and ZP20 (GCGATCCCCA), currently used to type Escherichia coli (also referred to as 1247 and 1283, respectively [9, 14]), were employed in the RAPD analyses. Reactions were carried out in a 40-μl reaction volume containing 2 μl of primer (20 pMol), 4 μl of 10× buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Triton X-100 [pH 8.8]), 1.5 U of DyNAzyme II (Finnzymes), and 500 ng of DNA, with a hot-start program consisting of an initial denaturation of 2 min at 94°C, followed by 40 cycles each of 60 s at 94°C, 60 s at 36°C, and 60 s at 72°C, with a final 5-min elongation at 72°C. Amplification products were subjected to 1% agarose gel electrophoresis in 0.5× TAE (20 mM Tris-acetate, 0.5 mM EDTA) buffer. Pictures of the ethidium bromide-stained gels were captured with a black-and-white camera (Kappa GmbH) coupled with a NuVista image card, digitalized in TIFF format, and delivered to all laboratories.

(GACA)4 analyses.

Amplification reactions were performed using 100 pmol of the repetitive oligonucleotide (GACA)4 as single primer, a 100 μM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Boehringer Mannheim GmbH, Mannheim, Germany), 3 mM MgCl2 (Perkin-Elmer Italia, Monza, Italy), 10× reaction buffer (500 mM KCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3]; Perkin-Elmer), 0.5 U of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer), and 400 ng of DNA sample. PCR was performed in a GeneAmp PCR system 2400 thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer), with an initial cycle of 5 min at 94°C; 38 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 47°C, and 60 s at 72°C; and a final cycle of 5 min at 72°C. Amplification products were subjected to 1.4% agarose gel electrophoresis in 1× TBE. (0.089 M Trizma base, 0.089 M boric acid, 0.002 M EDTA [pH 8.4]; Sigma-Aldrich, Milan, Italy). Pictures of the ethidium bromide-stained gels were captured digitally in TIFF format as described above and delivered to all laboratories.

CHEF procedure.

Chromosomal DNA was subjected to pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (1% agarose gel) in 1× TAE buffer at 14°C, employing a CHEF apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories) with a multistate program consisting of a first 72-h block at 2 V/cm, with the switching time linearly ramping from 20 to 24 min, and a second 7-h block at 6 V/cm, with the switching time linearly ramping from 25 to 145 s. Pictures of the ethidium bromide-stained gels were captured with a black-and-white camera (Kappa GmbH) coupled with a NuVista image card, digitalized in TIFF format, and delivered to all laboratories.

DAS.

The analysis system under development at DBVPG (the DBVPG analysis system [DAS]) includes free domain applications available from the Internet and link applications run in Excel to ensure a multiplatform usage. The system consists of the following operations:(i) measurement of the migration distance of each band from the well; (ii) calculation of the molecular weight of each band using a regression equation obtained with the migration distance and molecular weight values of a reference pattern, always included in the gels; (iii) classification of the molecular weight data; and (iv) statistical or phylogenetic analysis.

(i) Migration distance measures

The measures of migration distance data were obtained with the freeware package NIH-Image 1.62 (available with full instructions from its own web page: [http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/index.html] in both Macintosh and PC versions) by using either the automatic reading of densitometric peaks in the gel macro, or the haircross tool. In our hands, both procedures yielded very similar data series; the second was, however, preferred because it allows detection of the bands directly on the gel.

(ii) Regression analysis

Regression analysis was carried out with the MacCurve Fit 1.5 software using a polynomial regression-fitting algorithm of third degree in order to avoid biphasic trends of the curves. The obtained equation was then used to convert the migration distance data (from NIH-Image) into the corresponding molecular weight values. Only regressions with an R value not lower than 0.99 were processed.

(iii) Classification of molecular weight data

An Excel-based macro, Classify 1.3 (freely available from the corresponding author), was used to classify the molecular weight data. The upper limit of the molecular weight classes was defined according to the following formula: max(i + 1) = maxi × (100 − CA)/CA, where max(i + 1) is the upper limit of the (i + 1)th class, maxi is the upper limit of the ith class, and CA is the class amplitude.

Lower limits were simply as follows: min(i + 1) = maxi + 1, where min(i + 1) represents the lower value of the (i + 1)th class. CA values normally range from 5 to 10.

By using this algorithm the class amplitude decreases with the decreasing of the absolute molecular weight value, obtaining narrower classes for the lighter bands and wider classes for the larger bands. This situation produces very precise assignments of the low-molecular-weight data corresponding with the best-resolved bands of the lower part of the gel.

Classified values were arranged automatically in a matrix of discrete values (1 = presence of the band in the class; 0 = absence), referred to hereafter in this work as the binary matrix, representing the output of the third step.

Binary matrices were introduced in the SPSS program (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill.) for the statistical cluster analysis, carried out according to the Ward algorithm, using Euclidean distance.

Analyses with commercial packages

Comparison of fingerprinting patterns was performed by Diversity One (DO) software V 1.3 (PDI, Huntington Station, N.Y.) and with the molecular Analyst Fingerprint (MA) software (Bio-Rad). The DO software is able to calculate the molecular weight of each band of the different fingerprints using as reference the appropriate molecular weight size standards and correcting gel distortion in order to minimize mistakes in the molecular weight calculation. According to their molecular weights, bands were then matched with 5% tolerance. The overall comparison of the different fingerprints was then performed defining a similarity matrix and applying the neighbor-joining method to construct the dendrogram.

Gel analyses by MA fingerprinting (Bio-Rad) were carried out following the automatic routine using 4% drift (tolerance) and the Dice coefficient to calculate distances among strains. Dendrograms were generated with the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean algorithm.

Organization of the multicenter comparison

RAPD, (GACA)4, and CHEF analyses were performed separately in three laboratories: DBVPG (Perugia), Dipartimento di Medicina Sperimentale e Scienze Biochimiche (Perugia Hospital), and Istituto di Igiene e Medicina Preventiva (Milan); upon digitalization, the same pictures of the four gels were distributed to the three centers for separate analysis in order to exclude experimental variability due to the molecular procedures. According to this scheme, variations in the final dendrograms should be exclusively attributed to the differences in the analytical systems. In order to allow an easy, visual comparison, all dendrograms were graphically processed at DBVPG to normalize their dimensions, leaving untouched both the shape (topology) and the proportional lengths of the branches.

It might be useful to point out here that the production of binary (1 = present; 0 = absent) matrices, reporting the data from a gel, can be accomplished with two systems, which use the migration distance or the molecular weight values to assign the bands to predefined classes. In principle, both systems should perform equally well, although some inconvenience apparently affects the application of the routine based on the migration distances (4).

The two commercial packages employed in this study classify bands according to their migration distance, while DAS uses molecular weight values.

RESULTS

RAPD dendrograms

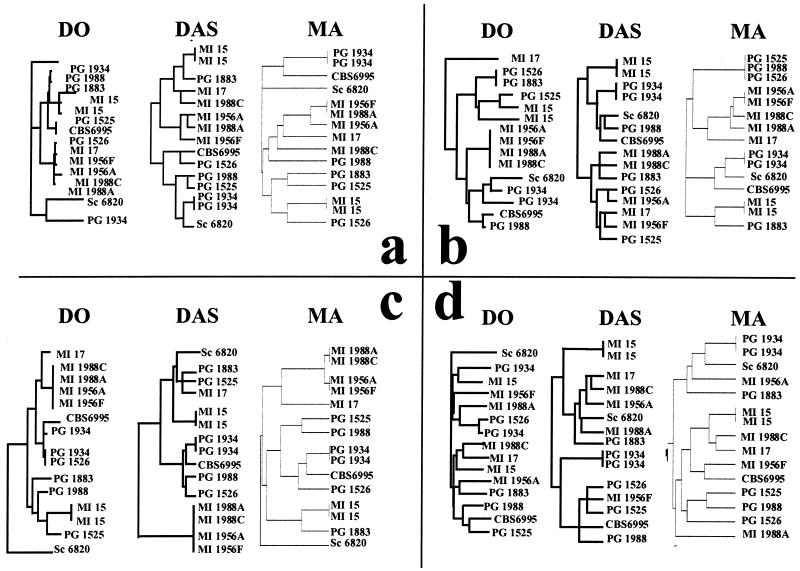

Dendrograms coming from the RAPD analysis carried out with the primer ZP19 (Fig. 1a) show that banding patterns of the same strains run into two separate lanes (MI 15 and PG 1934) are recognized as identical by both the MA system and DAS (Fig. 2a). Conversely, the DO system discriminates the two repetitions of PG 1934 and of MI 15 as divergent patterns. Both the DAS and DO systems recognize the S. cerevisiae strain DBVPG 6820 as the outgroup, whereas the MA system places it on the upper extremity of the dendrogram, relatively close to the PG 1934 duplicate strains. It should be remarked that RAPD analysis is designed to characterize strains within the species level and that it is normally not amenable to species discrimination. In the present study, a strain of another species has been included only to have a strongly divergent outgroup. Interestingly, the DAS dendrogram divides the strains into two major groups. The upper group includes all strains from Milan, with the sole exception of PG 1883, whereas the other comprises the strains from Perugia. This recognition of geographical distribution is not reproduced in either of the two commercial packages, maybe because of the different algorithms used to build up dendrograms.

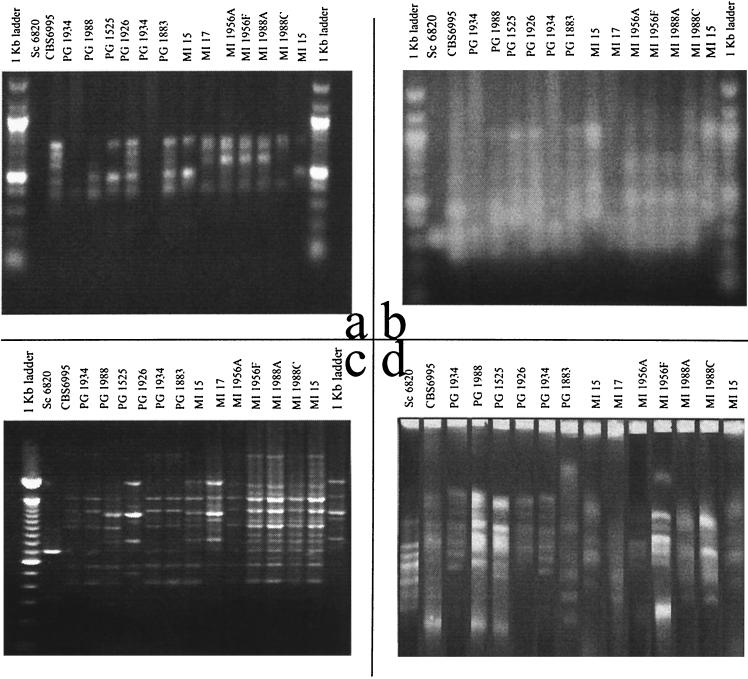

FIG. 1.

Pictures of gels analyzed to produce the dendrograms in Fig. 2. (a) RAPD obtained with the primer ZP19; (b) RAPD analysis obtained using the primer ZP20; (c) gel with (GACA)4 patterns; (d) electrokaryotypes (CHEF). Strain labels refer to Table 1.

FIG. 2.

Dendrograms obtained with each of the three analytical procedures under comparison. Dendrograms of RAPD obtained with primer ZP19 (a), RAPD obtained with primer ZP20 (b), (GACA)4 analysis (c), and CHEF banding patterns (d). Dendrogram dimensions were graphically normalized to allow an easy visual comparison of the topologies and of the relative distances among strain. See Table 1 for a list of strains used.

Dendrograms (Fig. 2b) of the RAPD reactions with ZP20 (Fig. 2b) show once again that both DAS and the MA system are able to correctly detect the strain identities (PG 1934 and MI 15), whereas the DO system defines identical samples as similar strains. The S. cerevisiae strain is not recognized as an outgroup, confirming that RAPD analysis is not always reliable at the species level. The DO system defines the strains MI 1956 A and F and MI 1988 A and C as identical, whereas the MA system defines the latter strains as similar and the former as identical. Conversely, DAS regards the two MI 1988 strains as similar and the two MI 1956 strains as different.

(GACA)4 dendrograms.

PCR analysis with (GACA)4 (GACAGACAGACAGACA) primers has been extensively used (7, 10) to differentiate among varieties and serotypes of C. neoformans because of the ability to produce patterns with several well resolved bands.

Dendrograms (Fig. 2c) obtained from the gel with the (GACA)4 products (Fig. 1c) show that again the DO system fails to detect the identity between the two PG 1934 replicates, whereas the overall similarity among the strains MI 1956 A, MI 1956 F, MI 1988A, and MI 1988C and the strict relatedness among the PG 1934 and CBS 6995 strains are recognized by all three systems.

CHEF dendrograms.

Dendrograms (Fig. 2d) from CHEF profiles (Fig. 1d) show a strict relation among the MI 17 and MI 1988C strains in all three systems. DO fails to recognize the identities of the two PG 1934 and MI 15 replicates but is the only system to recognize that indeed the S. cerevisiae strain is the outgroup.

DAS produces a dendrogram formed by two clusters of strains, of which one includes strains isolated from individuals in Milan (with the exception of PG 1883) and the other includes strains isolated from individuals in Perugia (with the exception of MI 1956F). This observation confirms the ability of DAS to discriminate the Cryptococcus strains according to their geographic origin as already noted in the case of the analysis of the patterns obtained from ZP19 products (Fig. 2a).

Merging different data sets in one matrix.

An everyday situation in molecular epidemiology is the impossibility of accommodating in a single gel all strains studied by a given technique (e.g., RAPD or CHEF analysis). This hampers the analysis of banding patterns by methods that use as input the migration distances, because it is virtually impossible for the same band to migrate exactly the same distance in different electrophoretic runs. The above problems can be solved with DAS by preparing a single matrix with all molecular weight data obtained from separate gels. Another advantage of this system is the possibility of merging in a single matrix all data sets obtained by applying different techniques (RAPD and CHEF analyses, etc.) to the same strains to obtain a single dendrogram from all available information.

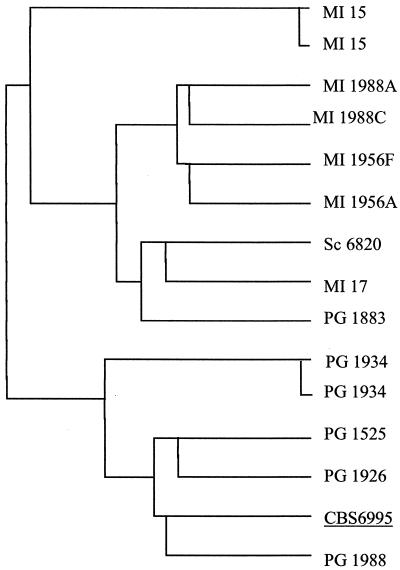

In order to test this feature of the DAS, we merged in a single matrix all data sets derived from the four molecular analyses described above, to draw a dendrogram according to Ward's algorithm calculated on the basis of the Euclidean distances. Results in Fig. 3 show that the strains considered are separated according to the geographic distribution, with only the exception of PG 1883, which falls in the cluster containing the isolates from Milan.

FIG. 3.

Comprehensive dendrogram calculated with DAS by pooling all data (RAPD with primers ZP19 and ZP20, [GACA]4, and CHEF) in a single matrix. Details of the procedure are illustrated in the text.

The consolidated dendrogram confirms the overall similarity between the type strain of C. neoformans (DBVPG 6995) and the isolates from Perugia as already observed in the separate analyses described above. The identities (PG 1934 and MI 15) are correctly detected, as well as the close relationship among the two pairs of isolates MI 1956 A and F and MI 1988 A and C, thus confirming a general trend already observed in all four separate analyses. Taken together, these observations indicate that the consolidation of data sets does not impair the correct detection of identities and similarities and makes possible the consideration of all data together, obviating the fragmentation of the raw data into a series of analyses difficult to summarize.

DISCUSSION

This study has shown that different systems can produce significantly divergent topological results, even when analyzing the same gel pictures, suggesting that care should be taken in comparing typing data from different laboratories. It is interesting that the differences among dendrograms, as shown in this study, are qualitative, i.e., relative to the topology of the trees. Quantitative variations, corresponding to branch lengths, could not be taken into consideration because of the different indices of distance used in the three analytical systems. This means that we could not show all of the differences between the three analytical systems, because only topology was effectively comparable. This situation is quite typical in the literature, when different indices of distance and different algorithms for the building of the trees are employed. A potential solution to this problem might be to separate and standardize all phases of the procedure necessary to transform a matrix into a dendrogram. The key steps of this process of standardization are the usage of molecular weight data and a correct choice of the analytical algorithms employed to calculate distances between strains and to build the tree.

The use of migration distances precludes the comparison of data coming from different laboratories, because the positions of the same bands in different gels vary even if care is taken to regulate the running conditions. Some commercial packages have tried to solve the problem by an artificial video alignment of the corresponding bands of identical molecular weight marker used in all gel runs. We have argued that this operation is legitimate only when the regression curve between migration distances and corresponding molecular weight values is linear, as in the case of many RAPD gels, but not when it has a hyperbolic shape, as in pulsed-field gel electrophoresis gels (4). These observations lead to the conclusion that the transformation of the migration distances into the corresponding molecular weights is an essential issue of the standardization process.

The choice of the algorithm to use in different cases is not always clear, although some procedures should be used prudently because they are not necessarily appropriate to the biological situation under study. The unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean, for instance, should not be used with organisms coming from environments with different (or unknown) selective pressures, because it assumes a constancy of variation rates (8). Even the algorithms to calculate statistical distances should be chosen carefully, considering that not all were designed for the purpose for which we tend to employ them. This can be the case of the Dice coefficient, introduced by Dice in 1945 for a study on species associations, which gives a weight of 2 to the double presence of bands and does not consider cases of double absence (6). It could be argued that in a RAPD profile both double presence and double absence of bands indicate similarity and that the presence of two bands of the same molecular weight is not a guarantee that indeed those two fragments of DNA represent the same DNA sequence. These few examples of criticism aim not to open a controversy but rather to stress the need for consensus analytical systems able to produce results immediately comparable by all investigators of the same scientific area and not affected by major statistical problems. Results presented in this paper suggest that all steps of each analytical routine need to be explicitly defined and standardized, according to the best performance found. In our opinion there are at least two strong requirements to achieve this goal: a wide discussion on the algorithms and an effective standardization of the software application employed.

During the review process of this article, in a paper dealing with comparisons between commercial software packages, we found that there are evident discrepancies between the three systems employed and that none provides an indisputably correct analysis (11). These findings confirm our conclusions and call for active research to solve the problem of the effective significance obtained with these systems of analysis.

Work is in progress in our laboratory to develop new procedures, aiming to give the investigator more choices of analysis to improve the overall flexibility of the system and to allow an effective comparison between different approaches. These procedures will be included in free software programs designed to interact with some of the most popular statistical or phylogenetic packages such as PHYLIP, PAUP, SPSS, ADE4, Le Progeciel.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Maria Anna Viviani and Massimo Cogliati (Laboratorio di Micologia Medica dell' Istituto di Igiene e Medicina Preventiva, Università degli Studi di Milano) for the gift of the MI isolates, for the (GACA)4 PCR fingerprinting of the strains included in the present study, and for performing the analysis with one of the commercial systems. We gratefully thank John Bennett (NIAID, NIH, Bethesda, Md.) and Helen S. Vishniac (Oklahoma State University) for their kind criticism and suggestions in reviewing the manuscript. We thank also the anonymous reviewers for their useful remarks.

This work was partially supported by grant ISS 1998-# 50A 0.01 of the Istituto Superiore di Sanità.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blasi, E., A. Brozzetti, D. Francisci, R. Neglia, G. Cardinali, F. Bistoni, V. Vidotto, and F. Baldelli. 2001. Evidence for microevolution in a clinical case of recurrent Cryptococcus neoformans meningoencephalitis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 20:535-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boekhout, T., A. van Belkum, A. C. Leenders, H. A. Verbrugh, P. Mukamurangwa, D. Swinne, and W. A. Scheffers. 1997. Molecular typing of Cryptococcus neoformans: taxonomic and epidemiological aspects. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47:432-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cardinali, G., G. Liti, and A. Martini. 2000. Non-radioactive dot-blot DNA reassociation for unequivocal yeast identification. Int. J. Syst. E vol. Microbiol. 50:931-936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cardinali, G., A. Martini, C. Tascini, and F. Bistoni. 1999. Critical observations on computerized analysis of banding patterns with commercial software packages. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:876-877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cardinali, G., L. Pellegrini, and A. Martini. 1995. Improvement of chromosomal DNA extraction from different yeast species by analysis of single preparation steps. Yeast 11:1027-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dice, L. R. 1945. Measures of the amount of ecologic association between species. Ecology 26:297-302. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia-Hermoso, D., G. Janbon, and F. Dromer. 1999. Epidemiological evidence for dormant Cryptococcus neoformans infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3204-3209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hillis, D. M., C. Moritz, and B. K. Mable. 1996. Molecular Systematics. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Mass.

- 9.Oethinger, M., S. Conrad, K. Kaifel, A. Cometta, J. Bille, G. Klotz, M. P. Glauser, R. Marre, and W. V. Kern. 1996. Molecular epidemiology of fluoroquinolone-resistant Escherichia coli bloodstream isolates from patients admitted to European cancer centers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:387-392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pernice, I., C. Lo Passo, G. Criseo, A. Pernice, and F. Todaro-Luck. 1998. Molecular subtyping of clinical and environmental strains of Cryptococcus neoformans variety neoformans serotype A isolated from southern Italy. Mycoses 41:117-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rementeria, A., L. Gallego, G. Quindos, and J. Garaizar. 2001. Comparative evaluation of three commercial software packages for analysis of DNA polymorphism patterns. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 7:331-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruma, P., S. C. Chen, T. C. Sorrell, and A. G. Brownlee. 1996. Characterization of Cryptococcus neoformans by random DNA amplification. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 23:312-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Viviani, M. A., H. Wen, A. Roverselli, R. Caldarelli-Stefano, M. Cogliati, P. Ferrante, and A. M. Tortorano. 1997. Identification by polymerase chain reaction fingerprinting of Cryptococcus neoformans serotype AD. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 35:355-360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang, G., T. S. Whittam, C. M. Berg, and D. E. Berg. 1993. RAPD (arbitrary primer) PCR is more sensitive than multilocus enzyme electrophoresis for distinguishing related bacterial strains. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:5930-5933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]