Abstract

Strains of newly emerging Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica (subspecies I) serotype 4,5,12:i:− causing food-borne infections, including a large food poisoning outbreak (n = 86) characterized by persistent diarrhea (14% bloody), abdominal pain, fever, and headache, were examined. The organisms were found in the stool samples from the patients. The biochemical profile of the organisms is consistent with that of S. enterica subsp. I serotypes, except for decreased dulcitol (13%) and increased inositol (96%) utilization. Twenty-eight percent of the strains showed resistance to streptomycin, sulfonamides, or tetracycline only; all three antimicrobial agents; or these agents either alone or in combination with ampicillin, trimethoprim, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. None of the serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains showed resistance or decreased susceptibility to chloramphenicol or ciprofloxacin. On pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), the strains showed 11 or 12 resolvable genomic fragments with 18 banding patterns and three PFGE profile (PFP) clusters (i.e., PFP/A, PFP/B, and PFP/C). Seventy-five percent of the isolates fingerprinted were closely related (zero to three band differences; similarity [Dice] coefficient, 86 to 100%); 63% of these were indistinguishable from each other (PFP/A1). PFP/A1 was common to all strains from the outbreak and 11 hospital sources. Strains from six other hospitals shared clusters PFP/B and PFP/C. PFP/C4, of the environmental isolate, was unrelated to PFP/A and PFP/B. Nine band differences (similarity coefficient, 61%) were noted between PFP/A1 and PFP/E of the multidrug-resistant S. enterica subsp. enterica serotype Typhimurium definitive type 104 strains. Whether these emerging Salmonella strains represent a monophasic, Dul− variant of serotype Typhimurium or S. enterica subsp. enterica serotype Lagos or a distinct serotype of S. enterica subsp. I is not yet known. Some of the phenotypic and genotypic properties of the serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains are described here.

The genus Salmonella currently has two species, Salmonella enterica and S. bongori. S. enterica is divided into the following subspecies: S. enterica subsp. enterica (subspecies I), S. enterica subsp. salamae (subspecies II), S. enterica subsp. arizonae (subspecies IIIa), S. enterica subsp. diarizonae (subspecies IIIb), S. enterica subsp. houtenae (subspecies IV), and S. enterica subsp. indica (subspecies VI). S. enterica subsp. I strains are usually isolated from humans and warm-blooded animals. Most of the Salmonella strains isolated in clinical laboratories belong to S. enterica subsp. I. The majority of the Salmonella serotypes belong to S. enterica subsp. I (4, 5, 12).

A serotype (as well as a serovar) is determined by the somatic (O) and flagellar (H) factor antigens present in the cell wall of Salmonella organisms (8). The total number of O or H factors present in each serotype varies from one to four different factors. The O factors determine the grouping, while the H factors completely define the serotype identity of a Salmonella strain. With several monophasic exceptions, the H antigens for each serotype are usually diphasic (e.g., S. enterica subsp. enterica [subspecies I] serotype 4,5,12:i:1,2). To date, about 2,435 different Salmonella serotypes have been identified; 59% of these account for S. enterica subsp. I (15). Any one of the above serotypes is a potential pathogen. The most commonly reported serotypes causing human infections are Enteritidis (∼38%) and Typhimurium (∼22%) (11; A. Agasan, J. Kornblum, G. Williams, L. Kornstein, R. Khakhria, W. Johnson, and A. Ramon, Abstr. 98th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. A-30, p. 43, 1998). Serotype Typhimurium carries the somatic (O 4,5,12) (also called group B) and diphasic flagellar (H i:1,2) antigens. Salmonella serotype Typhimurium is the archetype of a group B S. enterica subsp. I strain.

From January 1998 through December 2000, the Public Health Laboratories (PHL) confirmed 82 referral strains of a newly emerging serotype, 4,5,12:i:−, without the second-phase H antigen (monophasic). They were isolated from patients in 17 New York City (NYC) hospitals (HP), private laboratories (PL), and a single food poisoning outbreak (OB) involving 110 healthy adults attending a dinner reception in Queens, New York. The gastrointestinal illness (GI) manifested in this OB by 86 people was severe enough to require hospitalization of 31 of 44 persons (70%) who sought emergency consultation. Others (49%) reported receiving a prescription of antibiotics and taking time off from work or school for an average of 4 days.

Between 1994 and 1997, only seven probable serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains were identified at the PHL without notable epidemiologic associations. However, in 1998, a large increase in the number of serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains, including the OB strains (n = 47), was seen at the PHL. In addition, for the first time in 10 years, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; Atlanta, Ga.) confirmed 34 strains of serotype 4,5,12:i:− in 1998, followed by 44 in 1999 (3). At the same time, a rapid increase in the annual incidence (up to 3.7%) of serotype 4,5,12:i:− between 1993 and 1999 was reported in Spain (6). Serotype 4,5,12:i:− became the fourth and ninth most common serotype isolated from human and food sources in Spain, respectively.

The Spanish strains consistently exhibited resistance to the antimicrobial agents ampicillin, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, co-trimoxazole, and gentamicin. The strains were lysed only by Salmonella serotype Typhimurium phage 10 (phage type U302) (6).

The relative severity of the GI illness manifested by a large number of patients in the food poisoning OB, the increased number of serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains confirmed among HP in NYC, and the unique serologic and biochemical profiles of these Salmonella strains led us to examine further their phenotypic and genotypic properties.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Food poisoning OB.

Epidemiologic, environmental, and laboratory investigations of the food poisoning OB were conducted by the Bureau of Communicable Diseases (BCD), the Bureau of Environmental Investigations (BEI), and the PHL of the NYC Department of Health. Both BCD and BEI coordinated the distribution and processing of questionnaires for all persons involved in the OB. A questionnaire regarding demographics, food intake history, onset of illness, symptoms, and medical attention was administered by phone. The data obtained were then entered into the Epi-Info 6.02 program, and the food-specific attack rates were calculated. A case of illness was strictly defined as at least three episodes of diarrhea per day, abdominal pain, and fever. Stool samples from nonhospitalized ill persons and food handlers were collected and sent to the PHL for pathogen isolation and identification. Salmonella isolates obtained from HP and PL were likewise referred to the PHL for confirmatory testing and serotyping.

Sources of Salmonella cultures.

The Salmonella cultures were obtained as referrals for confirmatory testing from HP and PL located within the five boroughs of NYC and/or as isolates from stool specimens received directly at the PHL. The stool specimens were collected from OB cases, NYC child health clinics, and food handlers. From January 1998 to December 2000, the PHL confirmed a total of 5,063 Salmonella strains by serotyping; 82 (1.6%) of these were serotype 4,5,12:i:−. Of these 82 strains, 77 were received as referral cultures from HP over time and 5 were obtained as isolates from directly received stool samples. The referral cultures were obtained from 55 non-OB-related patients, 21 OB-related patients, and a sample of raw chicken meat unrelated to the OB (environmental or EN strain). The 5 isolates were obtained from four OB cases and from a paient at a child health clinic. The OB-associated strains were confirmed between July and August 1998; 22 were from guests and 3 were from food handlers who were also identified as cases in the OB. The majority of the patients involved in the OB were admitted to three NYC hospitals. Three OB cases were also identified in Connecticut. The strains were forwarded to the NYC PHL by the Connecticut Public Health Laboratories and were subsequently reconfirmed as serotype 1,4,5,12:i:−. Except for the EN strain, all serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains were isolated from stool samples from patients.

Identification of cultures.

The stool samples (n = 5) received for Salmonella culturing were processed as follows. They were grown on MacConkey (Difco, Detroit, Mich.), Hektoen (Binax/Nel, Waterville, Maine), bismuth sulfite (Difco), and salmonella-shigella agar (Difco) plate media for 18 to 24 h and in selenite (Binax/Nel) and GN (Difco) enrichment broths for 12 to 15 h at 35 to 37°C. After incubation, a loopful of growth from the enrichment broths was streaked onto the same set of plate media and incubated overnight at 35°C. Suspicious colonies from the plate media were examined; picked; inoculated into triple sugar (TS) medium (prepared in-house using Difco components), sulfide-indole motility (SIM) medium (Difco), veal infusion agar (VIA) slant (Difco), and Trypticase soy broth (TSB) (Difco); and grown overnight at 35°C. Similarly, the referral cultures (n = 77) submitted as pure Salmonella isolates from HP and PL sources were also reinoculated into TS, SIM, and VIA media and TSB. Pure growth on TS slants (alkaline slant/acid and gas in butt) was tested biochemically. Eight strains known to be serotype Typhimurium were also tested in parallel.

Biotyping.

All serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains were tested biochemically with different tests and substrates according to the tests and methods recommended by the CDC (9). The biochemical tests were designed to identify the Salmonella cultures by genus, species, and subspecies. The tests and substrates used (n = 34) were as follows: indole, methyl red, Voges-Proskauer, Simmons citrate, motility, hydrogen sulfide, urea agar, lysine decarboxylase, arginine dihydrolase, ornithine decarboxylase, phenylalanine deaminase, malonate, sodium acetate, cellobiose, glycerol, esculin, beta-galactosidase, nitrate, glucose, lactose, sucrose, mannitol, dulcitol, salicin, adonitol, inositol, sorbitol, arabinose, raffinose, rhamnose, maltose, xylose, trehalose, and melibiose. Results of tests were compared with standard results published by the Enteric Bacteriology Laboratories of the CDC (9) and then analyzed by using the CDC Matrix program, version 2-90. All cultures identified as Salmonella organisms biochemically were confirmed serologically.

Serotyping.

The Salmonella serotypes were confirmed by using the modified (7, 8, 15) slide typing scheme of Gruenewald et al. (10). To determine the somatic O serotype, polyvalent salmonella group A through G antisera (Difco), polyvalent salmonella O group A through I and Vi antisera (Difco; CDC; and SAS, San Antonio, Tex.), and single salmonella O factor 62 through 67 (except for 64) antisera (CDC and SAS) were tested against a mercuric chloride suspension of the organism. The suspension was made by transferring a swab of the bacterial growth on VIA medium into a sterile tube containing 3 ml of 0.08% mercuric chloride in 0.85% sodium chloride solution. The H (flagellar) antigens, on the other hand, were identified by using formalinized TSB growth (1:1 mixture of TSB and 0.6% formalin in normal saline solution) and H antiserum reagents prepared according to the manufacturers' instructions with sterile phosphate-buffered saline as a diluent (Difco, CDC, and SAS). The procedure for O serotyping was followed for H serotyping. For unexpressed H factor(s), phase reversal was carried out as described below.

Phase reversal typing.

The plate (8, 10, 15) and tube (12) methods were used to express the presence of the second-phase H antigen of serotype 4,5,12:i:−. A series of up to 10 repeat tests with a combination of the plate and tube methods were performed for each serotype 4,5,12:i:− culture. Weakened or complete inhibition of the H factor (H:i) and the absence of a detectable second-phase H factor (H:1,2) in serotyping were taken to represent successful phase reversal.

Antibiotic resistance testing.

Antibiotic resistance tests were performed by agar disk diffusion methods (Kirby-Bauer) according to the protocols and interpretive guidelines of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) (14). The following antibiotics (Remel Inc., Lenexa, Kans.) were tested: ampicillin, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, trimethoprim, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and ciprofloxacin. Interpretation of zone sizes was done by using Biomic software (Giles Scientific Inc., Santa Barbara, Calif.).

PFGE.

For pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), preparation of DNA embedded in agarose was carried out by standard procedures (2, 13). One-half of a plug was digested with XbaI. One-half of the digested material was loaded onto a 1% agarose gel. Electrophoresis was performed with a Bio-Rad (Hercules, Calif.) CHEF DR III apparatus. The gel was stained with ethidium bromide, destained, and digitally photographed with a Gel Doc 1000 system (Bio-Rad). Patterns were analyzed by visual comparison of the printed digital gel images. Relatedness was determined by calculating the similarity (Dice) coefficient (SD) for pairs of patterns (5) using the formula SD = 2nAB/nA + nB × 100, where nAB is the number of bands common for A (reference pattern) and B (compared pattern), nA is the total number of bands in A, and nB is the total number of bands in B. Patterns with an SD of 100% were considered indistinguishable, those with SDs of 99 to 85% were probably related, those with SDs of 84 to 75% were possibly related, and those with an SD of 74% or less were unrelated (16).

RESULTS

Symptomatology of cases in the OB.

Of the 88 (out of 110) people interviewed, 86 (98%) reported illness within 17.5 h after dinner. The symptoms included abdominal pain, diarrhea, fever, headache, nausea, and vomiting. The diarrheal episode lasted from 1 to 11 days (median, 3 days), with a median number of 10 abnormal bowel movements per day. Eleven of 82 persons (14%) with diarrhea reported bloody stools. Thirty-one of 44 persons (70%) who sought emergency consultation required hospitalization (1 to 4 days). Forty-nine percent of the respondents reported receiving a prescription for antibiotics, and 43% of them reported taking time off of work or school for an average of 4 days.

A case of illness in this OB was strictly defined as at least three episodes of diarrhea per day, abdominal pain, and fever. Forty-seven of 82 persons (55%) who experienced diarrhea met this strict case definition. Nineteen of 34 persons (56%) who submitted stool specimens tested positive for serotype 4,5,12:i:−. Table 1 summarizes the signs and symptoms experienced by persons representing positive cases in the OB. Other than the 1998 OB, however, no case history follow-up was carried out for unrelated hospital patients who were confirmed to have serotype 4,5,12:i:− infections.

TABLE 1.

Symptomatology for 19 patients involved in the food poisoning OB caused by a serotype 4,5,12:i:− strain in NYC in 1998a

| Major symptom | % of patients with major symptom | Related symptom(s) | % of patients with related symptom(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Headache | 100 | Muscle or joint pains | 89 or 79 |

| Diarrhea | 95 | Liquid or bloody stools | 95 or 21 |

| Abdominal pain | 95 | Gas or bloating | 79 or 79 |

| Nausea | 95 | Vomiting | 84 |

| Fatigue | 95 | Flu-like symptoms | 89 |

| Fever | 89 | Chills (100.4 to 105°F) | 79 |

| Loss of appetite | 84 | Weight loss (3-5 lb) | 79 |

As reported by the BCD. Illness was strictly defined as at least three episodes of diarrhea per day, abdominal pain, and fever.

Prevalent Salmonella serotypes.

Table 2 shows the 10 most common serotypes and the relative ranking of serotype 4,5,12:i:− (14th) among Salmonella serotypes confirmed at the PHL between 1996 and 2000. At least seven probable serotype 4,5,12:i:− isolates were already identified between 1994 and 1997. The peak number of isolates was seen in 1998 (n = 47), when a serotype 4,5,12:i:− strain was implicated in the Queens food poisoning OB. Other than the OB strains which were found in stool specimens from positive cases (n = 25) and the EN strain, which came from raw chicken, all other strains were obtained from unrelated hospital patients over time.

TABLE 2.

Relative ranking of serotype 4,5,12:i:− among the top 10 Salmonella serotypes from human sources in NYC from 1996 to 2000

| Rank | Serotype | No. of strains in the following yr:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | Total (%) | ||

| 1 | Enteritidis | 801 | 695 | 616 | 584 | 478 | 3,174 (35) |

| 2 | Typhimurium | 486 | 382 | 376 | 355 | 267 | 1,866 (21) |

| 3 | Heidelberg | 135 | 156 | 190 | 142 | 78 | 701 (8) |

| 4 | Typhi | 90 | 50 | 76 | 61 | 83 | 360 (4) |

| 5 | Hadar | 86 | 61 | 59 | 62 | 39 | 307 (3) |

| 6 | Agona | 22 | 51 | 41 | 38 | 16 | 168 (2) |

| 7 | Montevideo | 35 | 19 | 28 | 50 | 23 | 155 (1.7) |

| 8 | Newport | 33 | 18 | 29 | 47 | 12 | 139 (1.5) |

| 9 | Infantis | 28 | 12 | 12 | 28 | 44 | 124 (1.4) |

| 10 | Braenderup | 16 | 28 | 22 | 24 | 14 | 104 (1.2) |

| 14 | 4,5,12:i:− | 0 | 5 | 47a | 9 | 26 | 87 (1.0) |

| Other | 367 | 290 | 303 | 375 | 307 | 1,642 (18.2) | |

| Total | 2,126 | 1,806 | 1,842 | 1,808 | 1,413 | 8,995 (100) | |

Includes 25 OB strains and strain EN.

Medical interventions in the OB.

Due to the severity of the GI illness (8 to 100 diarrheal episodes/day), 17 of the 19 ill persons (89%) who submitted stool specimens sought hospital emergency consultation, while two (11%) went to consult a private physician; 13 of them (67%) required hospitalization. Time spent in the hospital lasted from 1 to 4 days. Antibiotics prescribed for 14 patients (76%) were amoxicillin, sulfamethoxazole, and levofloxacin.

Antimicrobial resistance profile of the serotype 4,5,12:i:− isolates.

Overall, 38% (26 of 68) of the serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains were susceptible to all antimicrobial agents tested; 34% (23 of 68) were less susceptible (intermediate) to either streptomycin, sulfamethoxazole, or tetracycline or a combination of the three; and 28% (19 of 68) were resistant to streptomycin, sulfamethoxazole, and tetracycline either alone or in combination with ampicillin, trimethoprim, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Table 3). Two of eight serotype Typhimurium strains tested were the definitive type 104 (DT104) strains. They were resistant to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, sulfamethoxazole, and tetracycline, and six were susceptible to all antimicrobial agents tested.

TABLE 3.

Antibiotic resistance profile of the serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains

| Profilea | No. of serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains in the following yr:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1998b | 1999 | 2000 | Total (%) | |

| Intermediate | ||||

| S | 6 (5) | 3 | 4 | 13 (19.1) |

| Su | 3 (2) | 0 | 0 | 3 (4.5) |

| T | 1 (0) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.5) |

| SSu | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 (4.5) |

| SuT | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (1.5) |

| ST | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 (2.9) |

| Subtotal | 23 (34.0) | |||

| Resistant | ||||

| S | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 (4.5) |

| Su | 1 (0) | 1 | 0 | 2 (2.9) |

| T (S) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (1.5) |

| S (T) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 (2.9) |

| Su (S) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.5) |

| SSu | 3 (0) | 0 | 0 | 3 (4.5) |

| SSuT | 1 (0) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.5) |

| ASu | 1 (0) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.5) |

| ASSu | 1 (0) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.5) |

| ASSuT | 1 (0) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.5) |

| SuTmSxT | 2 (0) | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.9) |

| SuTmSxT (S) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (1.5) |

| Subtotal | 19 (28.2) | |||

| Susceptible (all drugs) | 26 (18) | 0 | 0 | 26 (38.0) |

| Totalc | 47 (26) | 9 | 12 | 68 (100) |

S, streptomycin; Su, sulfamethoxazole; T, tetracycline; A, ampicillin; Tm, trimethoprim; SxT, Tm-Su. Drugs in parentheses indicate intermediate susceptibility. All strains tested were susceptible to both chloramphenicol and ciprofloxacin.

OB strains and EN strain.

Fourteen strains could not be tested.

Biotyping.

All serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains (n = 73) tested gave identical biochemical reactions in 29 of 34 tests and with substrates used to differentiate Salmonella species and subspecies. All serotype 4,5,12:i:−strains were identified as S. enterica subsp. I (adjusted score, 88%; CDC Matrix program, version 2-90), with incompatibilities noted in the fermentation of dulcitol (Dul) and inositol (Ino). The majority of the serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains were Dul− (87%) and Ino+ (96%). A classic S. enterica subsp. I strain is Dul+ (96%) and Ino− (35%), or biotype 1 (Dul+ Ino−). Two S. enterica subsp. I biotype variants were identified among the serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains, i.e., biotype 1A (Dul+ Ino+) and biotype 2 (Dul− Ino+). Sixty-three of 73 strains tested (87%) were biotype 2; 9 strains (12%) were biotype 1A; and only 1 serotype 4,5,12:i:− strain (1%) was biotype 1 (Table 4). All 25 OB strains were biotype 2.

TABLE 4.

Biotype variants of the serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains

| Biotypea | No. of strains in the following yr:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | Total (%) | |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| 1A | 3 | 4 | 2 | 9 (12) |

| 2 | 43 | 5 | 15 | 63 (87) |

| Total | 47 | 9 | 17 | 73 (100) |

See text for biotype definitions.

PFPs.

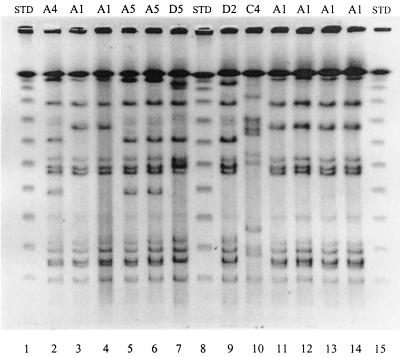

The serotype 4,5,12:i:− isolates had 18 banding patterns determined by PFGE analysis, with 11 or 12 resolvable genomic fragments per isolate. They were divided into three PFGE profile (PFP) clusters (i.e., PFP/A1 to PFP/A7, PFP/B1 to PFP/B7, and PFP/C1 to PFP/C4) (Table 5 and Fig. 1), with PFP/A1 being the predominant pattern (indistinguishable). Relative to PFP/A1, cluster A had 0 to 3 band differences (bd) and 86 to 100% relatedness (SDs), cluster B had 4 to 6 bd (SDs, 75 to 85%), and cluster C had 7 to 15 bd (SDs, 35 to 72%). All 25 OB strains, along with 25 HP strains, were grouped in cluster A, 11 HP strains were grouped in cluster B, and 5 HP strains and the EN strain were grouped in cluster C.

TABLE 5.

PFPs of serotype 4,5,12:i:− (PFP/A, PFP/B, and PFP/C) and serotype Typhimurium (PFP/D and PFP/E) strains

| PFP | bd | SD (%) | No. of strains

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OB | HP | EN | Total | |||

| A1 | 0 | 100 | 24 | 18 | 0 | 42 |

| A2 | 1 | 96 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| A3 | 2 | 91 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| A4 | 2 | 91 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| A5 | 3 | 88 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| A6 | 3 | 87 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| A7 | 3 | 86 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| B1 | 4 | 85 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| B2 | 4 | 83 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| B3 | 4 | 82 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| B4 | 4 | 82 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| B5 | 6 | 75 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| B6 | 6 | 75 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| B7 | 6 | 75 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| C1 | 7 | 72 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| C2 | 7 | 70 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| C3 | 11 | 52 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| C4 | 15 | 35 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total (serotype 4,5,12:i:−) | 25 | 41 | 1 | 67 | ||

| D1 | 5 | 76 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| D2 | 6 | 75 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| D3 | 6 | 75 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| D4 | 6 | 73 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| D5 | 6 | 70 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| E | 9 | 61 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Total (serotype Typhimurium) | 0 | 8 | 0 | 8 | ||

FIG. 1.

PFP profiles (shown above lanes) of the serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains from the OB (lanes 11 to 14), HP (lanes 2 to 6), and the EN (lane 10) and serotype Typhimurium DT104 strains (lanes 7 and 9) (NYC, 1998). STD, standard.

The predominant pattern, PFP/A1, was used as the reference pattern in the PFP analyses. All OB strains except for one showed indistinguishable patterns (i.e., PFP/A1; SD, 100%). One isolate had two bd (SD, 91%) (PFP/A3) from PFP/A1. Among 25 HP strains in cluster A, 18 had PFP/A1 and 7 had the related PFP/A2 and PFP/A4 to PFP/A7 (SDs, 86 to 96%). All 11 HP strains in cluster B had 4 to 6 bd (SDs, 75 to 85%) and all 5 HP strains in cluster C had 7 to 11 bd (SDs, 52 to 72%) from PFP/A1. The EN strain, in cluster C (PFP/C4), had 15 bd (SD, 35%) from PFP/A1.

The serotype Typhimurium strains showed six banding patterns with 11 to 13 genomic fragments per isolate (i.e., PFP/D1 to PFP/D5 and PFP/E) (Table 5 and Fig. 1). Their PFPs differed from PFP/A1 of the serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains by five to nine bands, with low similarities (SDs, 61 to 76%).

Relationship between biotypes and PFPs.

Overall, 85% (55 of 65) of the serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains tested by PFGE had S. enterica subsp. I variant biotype 2, 14% (9 of 65) had S. enterica subsp. I variant biotype 1A, and only 1% (1 of 65) had the classic S. enterica subsp. I biochemical profile. The relationship between PFP cluster and biotype is shown in Table 6.

TABLE 6.

Relationship between biotypes and PFPs of serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains

| Biotype | PFP (no. of strains) | Total no. (%) of strains |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | B3 (1) | 1 (1) |

| 1A | A1 (1), B5 (3), B7 (2), C3 (2), C4 (1) | 9 (14) |

| 2 | A1 (42), A2 (1), A3 (1), A4 (1), A5 (1), A6 (2), A7 (1), B1 (1), B2 (2), B4 (1), B6 (1), C2 (1) | 55 (85) |

| Total | 65 (100) |

Relationship between antibiogram and PFPs.

Table 7 shows that 38% (19 of 50) of PFP/A, 36% (4 of 11) of PFP/B, and 33% (2 of 6) of PFP/C strains were susceptible to the eight antimicrobial agents tested (i.e., ampicillin, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, trimethoprim, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and ciprofloxacin). A total of 32% (16 of 50) of PFP/A, 36% (4 of 11) of PFP/B, and 50% (3 of 6) of PFP/C strains showed decreased susceptibility (intermediate) to streptomycin, sulfamethoxazole, and tetracycline. Showing single or combined resistance to ampicillin, streptomycin, sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, trimethoprim, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole were 30% (15 of 50) of PFP/A, 27% (3 of 11) of PFP/B, and 17% (1 of 6) of PFP/C strains. Sixteen of the 25 PFP/A OB strains (64%) showed susceptibility to all antimicrobial agents tested, 8 strains (32%) showed intermediate susceptibility to streptomycin and sulfamethoxazole, and 1 strain (32%) showed resistance to sulfamethoxazole only. On the other hand, the two serotype Typhimurium DT104 strains (resistant to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, sulfamethoxazole, and tetracycline) (PFP/D3 and PFP/D5) showed six bd, while two susceptible strains showed the least relationship (nine bd; SD, 61%; PFP/E) with PFP/A1.

TABLE 7.

Relationship between antibiotic resistance profiles (ARP) and PFPs of serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains

| ARPa | PFP cluster (no. of strains) | Total no. (%) of strains |

|---|---|---|

| Susceptible (all drugs) | A (19), B (4), C (2) | 25 (37.3) |

| Intermediate | ||

| S | A (9), B (3), C (1) | 13 (19.4) |

| Su | A (4) | 4 (6.0) |

| SSu | A (2), C (1) | 3 (4.5) |

| ST | A (1), C (1) | 2 (3.0) |

| T | B (1) | 1 (1.5) |

| Resistant | ||

| S | A (2), B (1), C (1) | 4 (6.0) |

| SSu | A (3) | 3 (4.5) |

| Su (S) | A (2) | 2 (3.0) |

| SuTmSxT | A (1), B (1) | 2 (3.0) |

| Su | A (1) | 1 (1.5) |

| T (S) | A (1) | 1 (1.5) |

| S (T) | A (2) | 2 (3.0) |

| ASu | A (1) | 1 (1.5) |

| SSuT | B (1) | 1 (1.5) |

| ASSu | A (1) | 1 (1.5) |

| ASSuT | A (1) | 1 (1.5) |

| Total | A (50), B (11), C (6) | 67 (100.0) |

See Table 3, footnote a.

DISCUSSION

There have been reports of serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains isolated from random cultures nationally (3), but this is the first documented food poisoning OB in NYC in which a serotype 4,5,12:i:− strain was implicated as the infectious agent. From January 1998 to the present (and compounded by the food poisoning OB in July 1998), a steep increase in the number of serotype 4,5,12:i:− isolates has been seen (n = 82) (Table 2).

Serologically, serotype 4,5,12:i:− is serotype Typhimurium or serotype Lagos without the second-phase H antigen (or the 1,2 factor). Thus, it is basically a monophasic form of the above serotypes. Biochemically, however, the serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains differed slightly but consistently from serotype Typhimurium strains as well as from other S. enterica subsp. I strains. The serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains were found to be largely Dul− (87%) and Ino+ (96%), in contrast to classic S. enterica subsp. I strains, which are Dul+ (96%) and Ino− (65%). Based on these sugar reactions, two variant biotypes (i.e., 1A and 2) were seen. A high correlation (87%) was seen between serotype 4,5,12:i:− and biotype 2 (Dul− Ino+) (Table 4). Only 12% of the serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains were biotype 1A (Dul+ Ino+), and only one isolate in 1998 (1%) was biotype 1 (Dul+ Ino−). The Dul and Ino sugar reactions served as convenient markers for detecting probable serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains among group B isolates, which were monophasic at initial H antigen typing. A series of negative second-phase H antigen reversal typing results would confirm the laboratory identification of a serotype 4,5,12:i:− strain.

Based on our limited data, the SD (1) between serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains and other S. enterica subsp. I strains was about 85% (29 of 34). To be closely related, two strains should have a large number of positive test results in common (Jaccard coefficient, >95%) (1). Thus, a highly controlled biochemical test to compare serotypes is recommended.

The serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains also showed an antibiogram profile (Table 3) different from that of the NYC serotype Typhimurium strains (Agasan et al., Abstr. 98th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol.). While 72% of our serotype Typhimurium strains were resistant to at least one antimicrobial agent (65% multidrug resistant and 50% resistant to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, sulfamethoxazole, and tetracycline [mostly DT104]), only 34% of our serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains showed resistance to either streptomycin, sulfamethoxazole, or tetracycline and only 11% showed additional resistance to either ampicillin, trimethoprim, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. In addition, unlike most serotype Typhimurium strains, which showed resistance to the antibiotic chloramphenicol (∼70%), none of our serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains showed resistance to chloramphenicol. A laboratory in Spain (6), however, found frequent resistance of their serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains to the antimicrobial agents ampicillin, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, gentamicin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, a multidrug resistance pattern found mostly among serotype Typhimurium DT104 strains (with the exception of gentamicin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole).

On PFGE analysis, the serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains showed less heterogeneity (i.e., 18 PFPs and 67 strains) than the serotype Typhimurium strains (6 PFPs and 8 strains). By Dice coefficient analysis (5), two related clusters (PFP/A and PFP/B) and one unrelated cluster (PFP/C) were found among the serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains. A predominant pattern (PFP/A1) (indistinguishable) comprised 63% (42 of 67) of the serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains typed. The remaining 13% were closely related, 15% were possibly related, and 9% were unrelated to PFP/A1. The isolate from raw chicken showed the most differences (15 bd; SD, 35%) from PFP/A1. In comparison, none of the eight serotype Typhimurium strains typed was likely related to PFP/A1 of the serotype 4,5,12:I:− strains (Table 5). Two serotype Typhimurium DT104 strains (resistant to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, sulfamethoxazole, and tetracycline) and four susceptible strains showed peculiar PFPs distinct from PFP/A1 of the serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains (6 bd; SD, up to 75%). The two other susceptible serotype Typhimurium strains with an antibiogram profile similar to that of the serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains showed the most differences (9 bd; SD, 61%) from PFP/A1.

It is tempting to speculate that serotype 4,5,12:i:− is related to but distinct from serotype Typhimurium or serotype Lagos; however, the above tests are not conclusive. A large number of serotype 4,5,12:i:− strains from different localities must be compared with serotype Typhimurium or serotype Lagos strains by numerous taxonomic methods, both phenotypic and genotypic, to establish a classification under S. enterica subsp. I. 16S rRNA analyses may be ideal.

Nevertheless, the enhanced pathogenicity exhibited by the 1998 OB strains of serotype 4,5,12:i:− among otherwise healthy adults in NYC certainly represents an evolved pathogen of clinical significance. In addition to establishing its taxonomy, as perhaps a new S. enterica subsp. I serotype, an accompanying study of the pathogenicity factors acquired by the organism may also prove interesting.

Acknowledgments

We thank Frances Marie Vincent for invaluable assistance in preparing the figures; the Enteric Laboratory staff (M. Backer, W. Perry, S. Yappow, J. Douglas, M. Toscano, E. Weiss, and P. Wilder) for assistance in retrieving the isolates; Frances Brenner of the Salmonella Unit, CDC, for invaluable suggestions on nomenclature; the Connecticut Public Health Laboratories for sending us the serotype 4,5,12:i:− isolates obtained from three cases; and the staff of the Canadian National Laboratory for Enteric Pathogens for sending us a copy of their 1997 annual summary of enteric pathogens.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baron, E., S. Weissfeld, P. Fuselier, and D. Brenner. 1995. Classification and identification of bacteria, p. 249-265. In P. Murray et al. (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 6th ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 2.Birren, B., and E. Lai. 1993. Pulse-field gel electrophoresis. A practical guide. Academic Press, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2000. Salmonella surveillance: annual tabulation summary, 1999. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga.

- 4.Cuff, W., R. Khakhria, D. Woodward, R. Ahmed. C. Clark, and F. Rodgers. 2000. Enteric pathogens identified in Canada: annual summary 1997. National Laboratory for Enteric Pathogens, The Canadian Science Centre for Human and Animal Health, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada.

- 5.Dice, L. R. 1945. Measure of the amount of ecologic associations between species. Ecology 26:277-302. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Echeita, M. A., A. Aladuena, S. Cruchaga, and M. A. Usera. 1999. Emergence and spread of an atypical Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotype 4,5,12:i:− strain in Spain. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3425.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edwards, P. R., and W. H. Ewing. 1972. Production of H antisera, p. 203. In W. H. Ewing (ed.), Identification of Enterobacteriaceae. Burgess Publishing Co., Minneapolis, Minn.

- 8.Ewing, W. H. 1986. The genus Salmonella, and antigenic schema for Salmonella, p. 181-318. In P. R. Edwards and W. H. Ewing (ed.), Identification of Enterobacteriaceae. Elsevier Science Publishing Co., Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 9.Farmer, J. J., III. 1995. Enterobacteriaceae: introduction and identification, p. 438-447. In P. Murray et al. (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 6th ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 10.Gruenewald, R., D. Dixon, M. Brun, S. Yappow, R. Henderson, J. Douglas, and M. Backer. 1990. Identification of Salmonella somatic and flagellar antigens by modified serological methods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:24-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hosek, G., D. Leschinsky, S. Irons, and T. J. Safranek. 1997. Multidrug-resistant Salmonella serotype Typhimurium--United States, 1996. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 46:308-310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McWhorter-Murlin, A. C., and F. W. Hickman-Brenner. Identification and serotyping of Salmonella and an update of the Kauffmann-White scheme. Salmonella Unit, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga.

- 13.Mermel, L., S. L. Josephson, J. Dempsey, S. Parenteau, C. Perry, and N. McGill. 1997. Outbreak of Shigella sonnei in a clinical laboratory. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:3163-3165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1997. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests, 6th ed. Approved standard M2-A6. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 15.Popoff, M. Y., and L. Le Minor. 1997. Antigenic formulas of the Salmonella serovars, 7th ed. WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Salmonella, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France.

- 16.Tenover, F., R. Arbeit, R. Goering, P. Mickelsen, B. Murray, D. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]