Abstract

Rotavirus is the most-common cause of severe diarrhea in young children. Complete rotavirus characterization includes determination of the antigenic type of the two outer capsid proteins, VP7 and VP4, designated G and P types, respectively. During a nationwide rotavirus surveillance study, genotype G4 frequency increased during the second year. To evaluate further the mechanism of emergence and the relationship among G4 strains, the genetic diversity of VP7 capsid protein in these samples was studied in detail. Overall nucleotide sequence divergence ranged from less than 0.1 to 19.5%, a higher divergence than that observed for other rotavirus G types (0.1 to 9%). Sequences were classified into two major lineages (designated I and II) based on their nucleotide distances. The most heterogeneous lineage was further subdivided into four sublineages (designated Ia to Id). Most Argentine sequences were of sublineages Ib and Ic, which were confirmed to be independent sequence clusters by parsimony analysis. This study describes different lineages and sublineages within G4 strains and shows that Argentine strains are distantly related to reference strain ST3. The appearance of at least two G4 genotype (sub)lineages during 1998 demonstrates that the increased frequency of these strains was due to the synchronized emergence of different groups of strains.

Rotavirus is the most-common cause of severe diarrhea in young children worldwide (7, 18). The virus contains a genome of 11 segments of double-stranded RNA surrounded by a triple-layered protein shell, consisting of a core, an inner capsid, and an outer capsid. Rotaviruses are classified into G and P types, according to the genetic and antigenic diversity of the two outer capsid proteins, VP7 and VP4, respectively (5). VP7 is a glycoprotein with nine regions that vary across serotypes, and three of them, regions A, B, and C (amino acids [aa] 87 to 99, aa 145 to 150, and aa 211 to 223, respectively), have been shown to be antigenically important (15). At least 14 G types have been identified, with G1 to G4 being the most common. P genotypes are determined by analysis of genome segment 4, and at least 20 different P genotypes have been identified (11).

During a nationwide rotavirus surveillance study conducted in several Argentine cities from October 1996 to September 1998, genotype G4 frequency increased during the second study year, from 5.1% of strains tested during the first year to 31.3% of strains tested during the second year. During 1998, G4 was the second most prevalent genotype in Argentina and the most-prevalent type in three Argentine cities (accounting for 64.3, 77.8, and 38.6% of strains tested in Rosario, Santa Fe, and Tucumán, respectively) (1). To the authors' knowledge, these are among the highest G4 prevalences reported.

Many enteric pathogens spread through contaminated foods and water. We have been operating under the understanding that rotavirus spreads by person-to-person contact or upon fomite exposure. The ability to identify genomic lineages is a tool that permits a better understanding of pathogen spread.

For rotaviruses, G1 and G2 types have been detected more frequently and therefore have been studied more (4, 14, 16, 21). Given that G4 rotavirus strains are a common cause of diarrhea in Argentine children, a greater understanding of the molecular epidemiology of these strains is required both to provide information relevant to the development of candidate vaccines and to monitor the success of future rotavirus vaccines.

This report provides results of an extensive study of the genetic variation of VP7 protein in G4 rotaviruses. The genetic relationship of G4 rotaviruses was analyzed to determine whether the emergence of G4 strains during 1998 in six out of seven Argentine cities was due to a point source appearance of a G4 rotavirus strain or the synchronized emergence of different G4 strains. We also compared Argentine G4 strains with similar strains from different countries to determine worldwide genetic variation and to better understand the nature of the evolution of G4 rotaviruses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Surveillance system.

Surveillance began in October 1996 and continued through September 1998. Sentinel units (SUs) were placed in the following large Argentine cities: Buenos Aires, Cordoba, La Plata, Mar del Plata, Mendoza, Resistencia, Rosario, Santa Fe, and Tucumán. Six SUs participated during the first year, and seven participated during the second year. This was a laboratory network that applied a common protocol, collecting epidemiological information and stool samples. A reference laboratory at the Viral Gastroenteritis Laboratory, National Institute for Infectious Diseases provided core support, collected data from the SUs, and typed the rotavirus strains. Each SU consisted of a hospitalization site and a virology laboratory. A virologist and a pediatrician were responsible for each SU.

The study was conducted with hospitalized patients, less 3 years of age, who presented with acute diarrhea of less than 5 days' duration.

Rotavirus diagnosis.

Bulk stool specimens (at least 1 g) were received in the virology laboratory at each SU, where they were kept at 4°C and tested for rotavirus within a week of collection. Pathfinder (Kallestad, Austin, Tex.) kits were used during the first study year, and Rotazyme II (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, Ill.) kits were used during the second study year at all sites, in both instances following the manufacturers' recommendations. After rotavirus diagnosis was completed, positive samples were kept at −20°C until shipping to the reference laboratory for further strain characterization.

Characterization of rotavirus strains.

Rotavirus prototype strains Wa, DS1, ST3, K8, 69 M, Ito (kindly provided by Roger Glass, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga.), OSU (provided by Fernando Fernandez, Instituto Nacional de Tecnologia Agropecuaria, Buenos Aires, Argentina), and F45 were cultivated in MA104 cells and used as controls for typing assays. Genotyping was carried out using a nested reverse transcription (RT)-PCR method, as previously described, with some modifications (3, 8). Rotavirus RNA was extracted from 10% fecal suspensions using TRIzol (Life Technologies Inc, Frederick, Md.), following the manufacturer's recommendations. Gene 9 was amplified using a pair of generic primers (primers Beg and End), and then a pool of internal primers for G1, G2, G3, G4, G5, and G9, with a consensus primer 9C1, was used. P genotypes were determined by a similar RT-PCR strategy (6). Agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining were performed to visualize resulting bands.

Sequence analysis.

Partial gene 9 (encoding VP7) DNA sequence was obtained from amplicons generated in the first round of the G-typing RT-PCR (20). DNA was purified with a commercial kit (Wizard PCR Preps; Promega) and then sequenced in both senses (ABI PRISM Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit; Perkin-Elmer, Applied Biosystems).

Phylogenetic analysis was performed on partial VP7 sequences (nucleotides 76 to 863) and on deduced amino acid sequences from aa 10 to 273. Raw sequence data were first analyzed by the CHROMAS software (version 1.3; McCarthy 1996, Griffith University, Gold Coast Campus, Southport, Queensland, Australia), and forward and reverse sequence data of each sample were aligned using the EditSeq and MegAlign programs (DNASTAR Inc. Software, Madison, Wis.) to obtain the final sequence. Complete alignment was performed with Clustal X, and the alignment was analyzed using Kimura 2 parameters as a method of substitution and neighbor joining to reconstruct the phylogenetic tree, using the DNAdist and Neighbor-Joining programs of the PHYLIP software package. The statistical significance of phylogenies constructed was estimated by bootstrap analysis with 1,000 pseudoreplicate data sets using the SEQBOOT program. The tree was displayed with the Treeview program.

In order to determine the evolutionary relationship among Argentine sequences, a parsimony analysis was conducted using MEGA version 2.0 (Kumar et al. 2001, Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, and Arizona State University, Tempe). The method was performed using heuristic search and close-neighbor interchange with a random option and with 500 bootstrap repetitions. The results were also supported with a consistency index and a retention index of 0.72 and 0.85, respectively. These indices are used as a measure of the accuracy of the obtained topology and are inversely related to the extent of homoplasy. The parsimony analysis resulted in many trees with the same minimal length (299), but sequences were equally distributed in all of them.

Statistical methods.

95% confidence intervals were obtained using the mean and standard error values after 500 bootstrap resamplings using MEGA software. Two-by-two contingency tables were tested by Fisher's exact test. To test the significance of distances within and among groups, the Mann-Whitney nonparametric test was used.

GenBank accession numbers.

The Argentine VP7 gene sequences described in this study have been deposited in the GenBank database and given the following accession numbers: AF3738889 through AF3738918.

RESULTS

G4 prevalence.

A total of 490 rotavirus-positive samples were received for characterization from October 1996 to September 1998 at the Viral Gastroenteritis Laboratory. Twelve (5.1%) of 234 samples tested were typed as G4 during the first year of study, while 80 (31.3%) of 256 samples tested were typed as G4 during the second year of study. All G4 samples were associated with P[8].

G4 strains were found only in Cordoba, La Plata, and Tucumán at low prevalences (2.6, 2.6, and 8.7%, respectively) during the first year of study, but they were found at every SU during the second year of study. In the second year, Mendoza, Cordoba, and Buenos Aires had low G4 prevalences (9, 4, and 17%, respectively), while higher prevalences were observed in La Plata, Resistencia, Rosario, Santa Fe, and Tucumán (24, 21, 64, 78, and 39%, respectively). Thus, G4 was the most prevalent type in Rosario, Santa Fe, and Tucumán during the second year of study. More detailed information on type distribution was previously reported (1).

Phylogenetic relationships.

Partial gene 9 sequences were obtained for 28 samples from different SUs participating in the study, including two from Buenos Aires (BA 958 and BA 1239), one from Cordoba (Cor 1751), one from La Plata (LP 1546), two from Mendoza (Men 1734 and Men 1741), four from Resistencia (Res 1717, Res 1723, Res 1724, and Res 1730), six from Rosario (Ros 972, Ros 981, Ros 983, Ros 987, Ros 990, and Ros 998), three from Santa Fe (SF 925, SF 928, and SF 931), and nine from Tucumán (Tuc 737, Tuc 1594, Tuc 1606, Tuc 1620, Tuc 1625, Tuc 1631, Tuc 1636, Tuc 1650, and Tuc 1662). Sequenced strains were randomly selected from total G4 strains of this study. Another two samples (from Ushuaia, Ush 2037, and from Misiones, Mis 864), which represented cities that did not participate of this study, were also sequenced and used for comparison. The remaining studied sequences were obtained from the GenBank database.

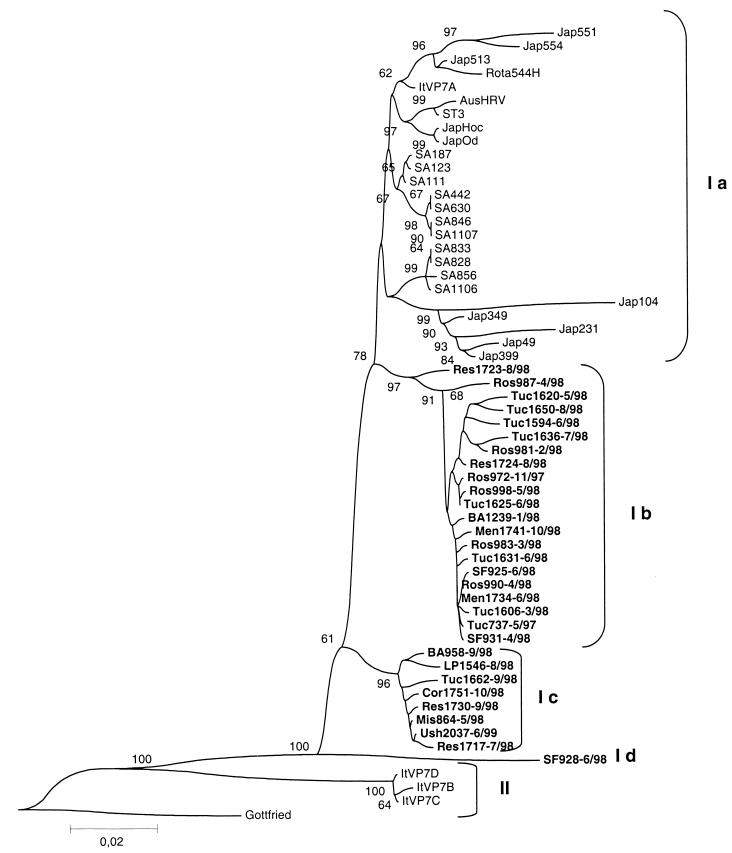

Figure 1 shows the phylogenetic tree obtained from the analysis of nucleotide sequences. Overall nucleotide divergence ranged from 0.1 to 19.5%. Analysis of the gene 9 sequence distance matrix data of these strains combined with their phylogenetic distribution demonstrated two major lineages (designated I and II). Lineage I also subdivided into four sublineages (designated Ia to Id). Although it is a one-member group, SF 928 was designated as sublineage Id based on differences with the remaining strains belonging to lineage I. Reference porcine strain Gottfried was comparably distantly related to the other strains at nucleotide level.

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of VP7 nucleotide sequences of genotype G4 strains. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Kimura and Neighbor-Joining programs of the PHYLIP package. Argentine strains and dates of collection (month/year) of the sample are in boldface type. Percentage bootstrap values above 60% are shown at the branch nodes. Abbreviations for locations: Jap, Japan; Aus, Australia; SA, South Africa; It, Italy; SF, Santa Fe; Tuc, Tucumán; Men, Mendoza; Ros, Rosario; BA, Buenos Aires; Res, Resistencia; LP, La Plata; Cor, Cordoba; Mis, Misiones; Ush, Ushuaia.

The relationship among lineages and sublineages is clearly shown in Table 1. The lineages were defined by 3.8 and 0.4% nucleotide distances, while distances between lineages were always higher than 13.9%. The nucleotide distances observed within lineage I compared with those observed within lineage II prompted us to subdivide lineage I into four sublineages at most 3.2% internal divergence. Divergence among sublineages clearly defines sublineages Ib and Ic, since distances within them are significantly lower than those compared to other groups (1.2 and 1%, respectively; P < 0.001). On the other hand, sublineage Ia is a more heterogeneous group, because divergence within it overlaps with divergence between this sublineage and sublineages Ib and Ic (confidence interval from 2.6 to 3.7 [Table 1]).

TABLE 1.

Percentages of nucleotide distances among G4 lineages and sublinages

| G4 lineage | Mean % nucleotide distance (95% confidence interval)a

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Lineage I

|

Lineage II | Gottfried | ||||

| Sublineage Ia | Sublineage Ib | Sublineage Ic | Sublineage Id | ||||

| Lineage I | 3.8 (3-4.6) | ||||||

| Sublineage Ia | 3.2 (2.6-3.7) | ||||||

| Sublineage Ib | 4.3 (3.2-5.3) | 1.2 (0.8-1.7) | |||||

| Sublineage Ic | 4.3 (3.2-5.5) | 5.1 (3.6-6.7) | 1 (0.6-1.4) | ||||

| Sublineage Id | 8.7 (6.6-10.9) | 8.6 (6.4-11.1) | 6.6 (4.4-8.8) | NAb | |||

| Lineage II | 15.3 (12.1-18.5) | 0.4 (−0.5-1.2) | |||||

| Gottfried | 15.4 (12.3-18.5) | 13.9 (7.4-20.4) | NA | ||||

Nucleotide distances within lineages or sublineages are presented in boldface type.

NA, not applicable.

Most sequences grouped within lineage I. Human reference strain ST3 grouped together with Japanese strains, South African strains, one strain from Australia, and one (ItVP7A) of the oldest strains sequenced from Italy into sublineage Ia. Italian sequences are divided in two lineages (Ia and II), correlating with a previously defined antigenic distinction as subtype A strains (ST3-like strains) and subtype B strains (10). Lineage II strains (ItVP7B, ItVP7C, and ItVP7D) grouped together with the lowest divergence within a lineage observed (0.4%). The porcine reference strain, Gottfried, was distantly related to the rest of the strains analyzed, with nucleotide divergence ranging from 14 to 19.5%.

Argentine sequences are divided among sublineages Ib, Ic, and Id, while strains from other countries constitute the rest of the clusters. To confirm the existence of different monophyletic groups of G4 Argentine strains within lineage I, a parsimony analysis was conducted. This analysis showed the clustering of all proposed sublineages into four different groups, supported by very high bootstrap values (data not shown). Argentine sequences also separated from sublineage Ia sequences, which have worldwide distribution. Again, strain SF 928 (sublineage Id) appeared distantly related to the rest of the strains analyzed.

A significant correlation was found between sublineages and date of collection, because almost every sample (89%) of sublineages Ic and Id was collected after the annual peak of rotavirus diarrhea in May 1998, while sublineage Ib samples were collected throughout the year (52 and 48% of samples before and after that date, respectively [Fisher's exact test, P = 0.005]). Although a significant correlation could not be established, it was noticeable that all sublineage Ic sequences corresponded to patients younger than 1 year of age, while sublineage Ib sequences had the same age distribution as previously reported for G4 strains (57% of children younger than 1 year of age) (1).

Finally, a preliminary analysis of partial VP4 sequences of G4 P[8] and G1 P[8] strains from this study was conducted. G4 P[8] strains clustered into one group previously established as (P[8]) lineage II, regardless of their classification into sublineages based on VP7 sequences (data not shown) (9, 12). These strains clustered into lineage II together with several G1 P[8] strains, while (P[8]) lineage I was found to contain exclusively G1 P[8] strains, as previously reported (13).

Amino acid variation among G4 strains.

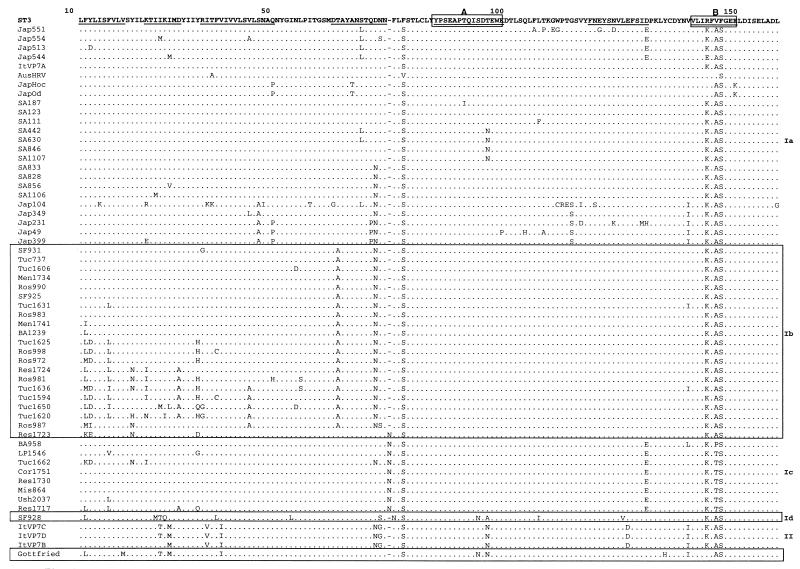

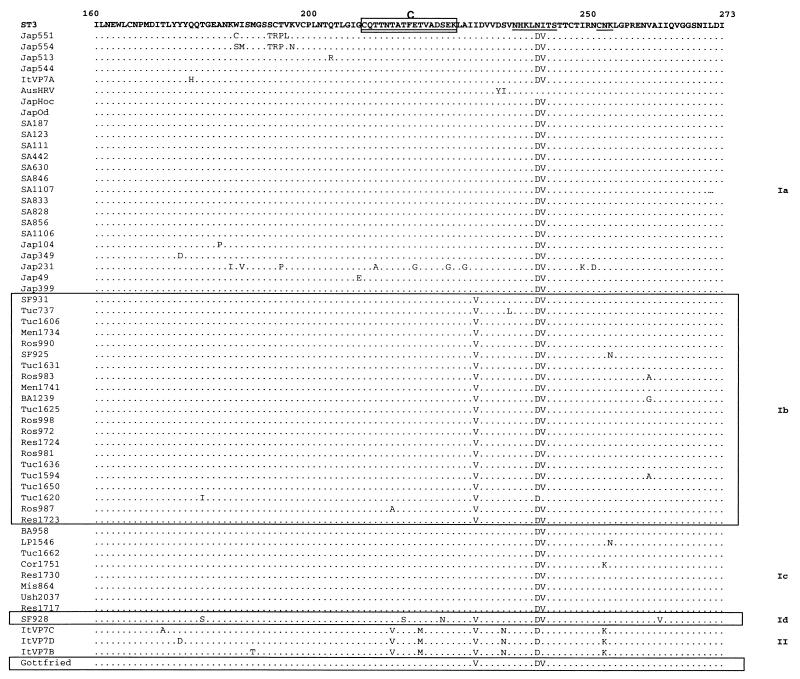

Figure 2 shows changes among deduced amino acid sequences of G4 strains compared with reference strain ST3.

FIG. 2.

Deduced amino acid sequences of G4 strains compared to sequence of reference strain ST3. Underlined amino acids indicate regions that are highly variable among G types. Antigenic regions are boxed and marked as A, B, and C, respectively.

Lineage and sublineage divisions defined by phylogenetic analysis of nucleotide sequences are also reflected in patterns of amino acid changes. In accord with their nucleotide divergence, the highest number of amino acid changes was found among lineage II strains, and most changes (15 of 20) were located in VP7 variable regions. Some of these changes were shared with reference strain Gottfried (e.g., threonine at position 28 or asparagine at position 98), which also had most changes (11 of 15) located in variable regions.

On the other hand, Argentine strains had unique amino acid substitutions that correlated with their separation into sublineages. The clearest examples are the insertion of an asparagine at position 77, glutamic acid at position 132, and proline or threonine at position 147, which are only observed in sublineage Ic sequences. The position 132 and position 147 substitutions are present in variable regions. Sublineage Ib sequences also showed defining amino acid changes, alanine at position 66, and substitution of isoleucine for valine at position 229, which was also shared with sublineage Id, lineages II, and reference strain Gottfried sequences. Again, most amino acid substitutions found in Argentine sequences were located in variable regions (12 of 13 for Tuc 1625). Despite this trend, few variable-region changes were located in the major neutralization epitopes (regions A, B, and C). In contrast, all sequences analyzed in this study were found to differ from strain ST3 within region B.

Two Argentine strains were distinct from the others. One sequence, that of Res 1723, appeared to be an intermediate between sublineages Ib and Ic. Despite clustering with a high bootstrap value with sublineage Ib, it had the asparagine insertion (aa 77) characteristic of sublineage Ic, while sharing other substitutions with sublineage Ib. The other strain, SF 928, was the only strain that did not cluster with other Argentine sequences, and it differed from them by the presence of several distinctive amino acid substitutions that were confirmed through repeated sequencing of its VP7 gene.

DISCUSSION

A nationwide rotavirus surveillance study carried out in Argentina between 1996 and 1998 allowed us to determine the prevalent genotypes (1). The prevalent rotavirus G types varied from season to season, and G4 prevailed during the second study year. Since G4 emerged as an important cause of rotavirus diarrhea in Argentina, a more-detailed study of the variability of G4 sequences was carried out.

Many studies report genetic variations among rotavirus strains of the same serotype and also describe sublineages of the same G type (4, 14, 16, 19, 21). Differing from other rotavirus G types, which seem to be more closely related, G4 strains exhibited a higher nucleotide divergence around the world. As an example, overall divergences of less than 7 and 3% were reported for G1 and G2, respectively (14, 21). Moreover, a recent study of G9 strains conducted by our laboratory reported nucleotide distances of less than 4% among G9 strains from very distant origins (2).

On the other hand, this study shows that G4 sequences presented nucleotide distance variations up to 20%. The greater differences found among G4 sequences led us to classify them into two lineages (I and II) and to classify lineage I into four sublineages, based on the divergence within it and the clustering observed in the phylogenetic tree. Two sublineages, Ib and Ic, were very homogeneous and were characterized by distinct amino acid changes. Sublineage Ia had greater divergence and had a distinct geographical distribution. This lineage could possibly be divided if more sequences were available.

VP4 analysis demonstrated that gene 4 sequences of all G4 strains were highly homologous. The clustering into sublineages did not correlate with the presence of a distinct VP4 sequence, suggesting that these G4 strains emerged after reassortment with homologous VP4 genes.

One of the main objectives of this study was to analyze the relationships among Argentine G4 sequences to determine the mechanism of emergence. The division into sublineages Ib and Ic, as two different monophyletic groups, was clearly shown in the parsimony analysis. Although the division was not associated with different sites of sample collection, this result demonstrates that rotavirus G4 infections in Argentina were caused by the emergence of at least two well-defined groups of strains. This observation allowed us to speculate that a low level of herd immunity to G4 rotavirus creates the optimal conditions in the community for the emergence of different G4 strains. In addition, a similar observation was previously reported during a study of G4 sequences in northern Italy (10). Not only were sublineages Ib and Ic differentiated by distinct amino acids, but they were also divided by a more drastic evolutionary event of codon insertion. Such events might lead to major changes in gene 9 protein properties and viral structure.

Notably, we found epidemiological differences between Argentine sublineages and dates of collection. It seems that sublineages Ic and Id emerged into the population after the annual rotavirus peak observed in May 1998, while sublineage Ib sequences were causing all G4 rotavirus infections before that time. The earliest sublineage Ic strain collected was Mis 864. This sample belongs to a group of 43 rotavirus-positive samples collected after an outbreak report during May 1998 in Misiones. Given that 60% of rotavirus-positive samples were typed as G4, one of them was selected for sequencing and was included for comparison. Our results support the idea that this outbreak might be the point source origin of the emergence of sublineage Ic.

Another two Argentine sequences had very special characteristics. Although we first hypothesized that Res 1723 could represent an intermediate sequence between sublineages Ib and Ic, parsimony analysis confirmed the association with sublineage Ib. Res 1723 could also be the prototype of a different sublineage, which could be determined if more sequences of this type were available. On the other hand, sample SF 928 had a unique sequence that differentiated it from the rest of the lineage I sequences.

The increased divergence present among G4 strains, even among strains that emerged within a single country as they did in Argentina and collected during a short period, could be explained if the strains emerged from different reservoirs (not only human). This becomes more evident when one considers the fact that the two largest groups of Argentine strains are independent from each other and not a sequential derivation from one another through evolutionary change, as might be expected. The implications of such differences in different aspects as immune response, severity of the disease, or efficacy of any available vaccine should be evaluated further (17).

This study identified lineages and sublineages within a series of G4 rotavirus isolates. Argentine strains were distantly related to reference strain ST3 and located in newly defined sublineages. The appearance of the Argentine sublineages differed by period of collection, patient age, and potential explosiveness of disease spread (in Misiones). This report demonstrates that the increased frequency of G4 rotavirus strains in 1998 was due to the synchronized emergence of different sublineages, one of which possibly originated from a point source outbreak.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bok, K., N. Castagnaro, A. Borsa, S. Nates, C. Espul, O. Fay, A. Fabri, S. Grinstein, I. Miceli, D. Matson, and J. Gomez. 2001. Surveillance for rotavirus in Argentina. J. Med. Virol. 65:190-198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bok, K., G. Palacios, K. Sirjvarger, D. O. Matson, and J. A. Gomez. 2001. Emergence of G9P[6] human rotaviruses in Argentina: phylogenetic relationships among G9 strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4020-4025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Das, B. K., J. R. Gentsch, H. G. Cicirello, P. A. Woods, A. Gupta, M. Ramachandran, R. Kumar, M. K. Bhan, and R. I. Glass. 1994. Characterization of rotavirus strains from newborns in New Delhi, India. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:1820-1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diwakarla, C. S., and E. A. Palombo. 1999. Genetic and antigenic variation of capsid protein VP7 of serotype G1 human rotavirus isolates. J. Gen. Virol. 80:341-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Estes, M. 1996. Rotaviruses and their replication, p. 1625-1655. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, R. M. Chanock, J. L. Melnick, T. P. Mouath, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Fields virology, 3rd ed., vol. 2. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia, Pa. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gentsch, J. R., R. I. Glass, P. Woods, V. Gouvea, M. Gorziglia, J. Flores, B. K. Das, and M. K. Bhan. 1992. Identification of group A rotavirus gene 4 types by polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:1365-1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glass, R. I., P. E. Kilgore, R. C. Holman, S. Jin, J. C. Smith, P. A. Woods, M. J. Clarke, M. S. Ho, and J. R. Gentsch. 1996. The epidemiology of rotavirus diarrhea in the United States: surveillance and estimates of disease burden. J. Infect. Dis. 174:S5-S11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Gouvea, V., R. I. Glass, P. Woods, K. Taniguchi, H. F. Clark, B. Forrester, and Z. Y. Fang. 1990. Polymerase chain reaction amplification and typing of rotavirus nucleic acid from stool specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:276-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gouvea, V., R. C. Lima, R. E. Linhares, H. F. Clark, C. M. Nosawa, and N. Santos. 1999. Identification of two lineages (WA-like and F45-like) within the major rotavirus genotype P[8]. Virus Res. 59:141-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green, K. Y., A. Sarasini, Y. Qian, and G. Gerna. 1992. Genetic variation in rotavirus serotype 4 subtypes. Virology 188:362-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoshino, Y., and A. Z. Kapikian. 1994. Rotavirus antigens. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 185:179-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iturriza-Gomara, M., J. Green, D. W. Brown, U. Desselberger, and J. J. Gray. 2000. Diversity within the VP4 gene of rotavirus P[8] strains: implications for reverse transcription-PCR genotyping. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:898-901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iturriza-Gomara, M., B. Isherwood, U. Desselberger, and J. Gray. 2001. Reassortment in vivo: driving force for diversity of human rotavirus strains isolated in the United Kingdom between 1995 and 1999. J. Virol. 75:3696-3705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin, Q., R. L. Ward, D. R. Knowlton, Y. B. Gabbay, A. C. Linhares, R. Rappaport, P. A. Woods, R. I. Glass, and J. R. Gentsch. 1996. Divergence of VP7 genes of G1 rotaviruses isolated from infants vaccinated with reassortant rhesus rotaviruses. Arch. Virol. 141:2057-2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kapikian, A. Z., and R. M. Chanock. 1996. Rotaviruses, p. 1657-1708. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, R. M. Chanock, J. L. Melnick, T. P. Monath, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Fields virology, 3rd ed., vol. 2. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia, Pa. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maunula, L., and C. H. von Bonsdorff. 1998. Short sequences define genetic lineages: phylogenetic analysis of group A rotaviruses based on partial sequences of genome segments 4 and 9. J. Gen. Virol. 79:321-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pager, C. T., J. J. Alexander, and A. D. Steele. 2000. South African G4P[6] asymptomatic and symptomatic neonatal rotavirus strains differ in their NSP4, VP8*, and VP7 genes. J. Med. Virol. 62:208-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parashar, U. D., J. S. Bresee, J. R. Gentsch, and R. I. Glass. 1998. Rotavirus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 4:561-570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramachandran, M., C. D. Kirkwood, L. Unicomb, N. A. Cunliffe, R. L. Ward, M. K. Bhan, H. F. Clark, R. I. Glass, and J. R. Gentsch. 2000. Molecular characterization of serotype G9 rotavirus strains from a global collection7. Virology 278:436-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanger, F., S. Nicklen, and A. Coulson. 1977. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:5463-5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zao, C. L., W. N. Yu, C. L. Kao, K. Taniguchi, C. Y. Lee, and C. N. Lee. 1999. Sequence analysis of VP1 and VP7 genes suggests occurrence of a reassortant of G2 rotavirus responsible for an epidemic of gastroenteritis. J. Gen. Virol. 80:1407-1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]