Abstract

Campylobacters are the most commonly reported cause of acute bacterial enteritis in the United Kingdom and United States, with poultry, milk, and water implicated as sources or vehicles of infection. The majority of campylobacter infections are sporadic, although outbreaks may occur, and these provide an opportunity to evaluate genotypic fingerprinting techniques. In this study, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was compared with single-enzyme-amplified fragment length polymorphism (SAFLP). The results for the three separate episodes indicated that SAFLP and PFGE both clustered the strains from the first incident as 100% homologous. The strains from the second and third incidents clustered as distinct from both the first incident and from each other. PFGE is well recognized as a discriminatory fingerprinting technique for campylobacters; however, SAFLP has proven to be equally discriminatory, but far less labor intensive and with the added advantages of less “hands-on” time and inexpensive equipment, it is an excellent alternative to PFGE for investigation of outbreaks.

In England and Wales, the incidence of campylobacter infections has risen dramatically since 1980, with 53,858 isolates reported in 2000 (www.phls.org.uk). Subtyping plays an important role in monitoring human campylobacter infections, and a wide range of genotypic methods have been used (11). While the discriminatory power of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) profiling is high for campylobacters (3, 5, 6, 9, 11), there are several disadvantages, including the low number of bands in each profile, making it less discriminatory. Single-enzyme-amplified fragment length polymorphism (SAFLP) has been described for Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi (8) and used successfully for Helicobacter pylori (4). The aim of this study was to compare the discrimination of SAFLP with PFGE for campylobacters as a possible alternative for use in investigation of outbreaks.

Strain selection.

The strains used in this study were isolated in South Wales during 1 month and referred to the Campylobacter Reference Unit (CRU) for identification and typing.

Cultures were stored on Cryobeads (Microbank; Prolab Diagnostics, Ontario, Canada) at −80°C, grown on Oxoid Colombia blood agar (Oxoid CM331; Unipath, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) containing 5% defibrinated horse blood, and incubated at 42°C for 24 h in anaerobic jars (Don Whitley Scientific, Shipley, West Yorkshire, United Kingdom) under microaerobic conditions (5% CO2, 5% O2, 3%H2, 87% N2).

Serotyping and phage typing.

Phenotypic typing was carried out as previously described by Frost et al. with the CRU protocols for serotyping and phage typing (1, 2)

PFGE.

Preparation of unsheared DNA for PFGE and digestion and electrophoresis were performed as described by Gibson et al. (3) with the restriction endonuclease SmaI (Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom). A lambda ladder (PFG marker; New England Biolabs, Hitchin, United Kingdom) was used to determine fragment sizes. Gels were stained with 1 mg of ethidium bromide ml−1 and transilluminated with UV light (UVP Dual Intensity Transluminator; Anachem, Luton, United Kingdom). Restriction fragment migration profiles were compared by using the Bionumerics program (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium).

SAFLP.

DNA was obtained from 24-h cultures grown at 42°C by the CTAB (hexadecyl trimethyl ammonium bromide) technique (12). The DNA was used directly, made up to a concentration of 0.266 μg/μl, and estimated with a Biophotometer (Eppendorf, Cambridge, United Kingdom), and the SAFLP method was carried out as described by Gibson et al. (4).

DNA was digested with the restriction endonuclease HindIII (Invitrogen) in a total volume of 20 μl containing 1 μl of 0.1 M spermidine (Sigma, Poole, United Kingdom), 2 μl of 10× buffer, and 2 μl of HindIII (Invitrogen) at 37°C overnight.

Ligation was carried out for 3 h at room temperature in a total reaction volume of 20 μl containing 5 μl of digested DNA, distilled water, 4 μl of 5× ligase buffer, 0.2 μg of Adapter H1 (5′ ACGGTATGCCACAG 3′) (MWG Biotech, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom), and 0.2 μg of Adapter H2 (5′ AGCTCTGTCGCATACCGTGAG 3′) (MWG Biotech), and 1 U of T4 DNA ligase (Invitrogen).

Digested ligated DNA was heated to 80°C for 10 min to inactivate the ligase, and subsequent PCR was carried out in an amplification mixture of 50 μl containing 200 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), 2.5 mM MgCl2 (Invitrogen), 300 ng of primer HI-C (5′ GGTATGCGACAGAGCTTX 3′) (MWG Biotech), and 1 U of Taq polymerase in 10× PCR buffer (Invitrogen) with 5 μl of digested, ligated DNA. (Note that primers with extensions of A, G, and T in position X were evaluated for discriminatory ability, with extension C producing the most fragments [data not shown].) PCR amplification was performed in a DNA Engine PTC-200 (MJ Research, Braintree, United Kingdom) and consisted of 1 cycle at 94°C for 4 min, followed by 33 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2.5 min.

PCR products were detected on a 1.5% agarose gel (Invitrogen) run alongside a 123-bp ladder (Invitrogen) at 100 V for 3 h, followed by staining in 1 mg of ethidium bromide ml−1, visualized under UV light, photographed, and analyzed both by eye and by Bionumerics.

Epidemiology.

In September 2000, a local increase in Campylobacter jejuni isolation rates occurred in South Wales, involving three cohorts of patients within a 35-mile radius. These included residents of a nursing home (isolate HS50 PT6 [incident 1]) and a housing estate (isolate HS23 PT1 [incident 2]). Incident 3 was a cot death, the isolate from which was untypeable by serotyping (HS UT) and reacted with the phages but did not conform to a designated type (PT RDNC).

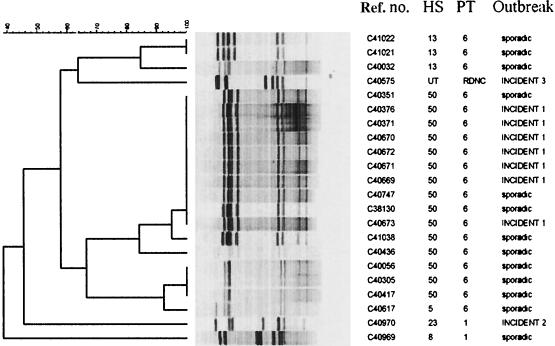

PFGE produced six to eight fragments ranging in size from 45 to 360 kb. When analyzed with Bionumerics, PFGE (Fig. 1) clustered all seven of the HS50 PT6 isolates from incident 1 as 100% homologous. Four sporadic HS50 PT6 strains also clustered with this profile. Incidents 2 and 3 both involved single isolates with unique profiles, distinct from each other and all sporadic isolates tested.

FIG. 1.

Dendrogram of PFGE patterns digested with SmaI. Cluster analysis was performed with Bionumerics (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium) by using the Dice correlation coefficient and the unweighted pair group mathematical average (UPGMA) clustering algorithm.

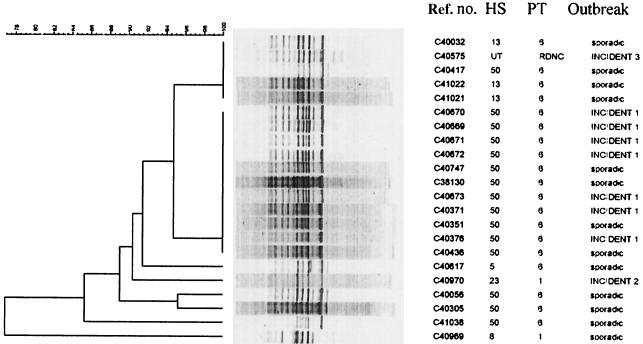

SAFLP (Fig. 2) produced 8 to 10 fragments ranging in size from 400 to 1,500 bp with primer HI-C and clustered the HS50 PT6 outbreak strains from incident 1 and four sporadic HS50 PT6 isolates as 100% homologous. Incident 2 had a unique profile. Incident 3 had a profile distinct from those of the other two incidents, but four isolates from apparently sporadic cases and with different serotypes clustered with 100% homology.

FIG. 2.

Dendrogram of SAFLP digested with HindIII. Cluster analysis was performed as for Fig. 1.

All methods used identified the nursing home outbreak agent as a single strain; however, it should be noted that both techniques grouped some of the sporadic strains with the outbreak strain. This demonstrates the importance of typing both outbreak and sporadic isolates in order to estimate the population prevalence of specific serotypes. In this study, comparisons were limited to serotypes known to be closely related to each other (2). Further work is needed to determine the relationships between PFGE and/or SAFLP profile and serotype or phage type. Since C. jejuni is not highly clonal, different typing methods may generate different clusters. However, within a single clone, all isolates should be the same with any combination of typing or fingerprinting methods.

PFGE is widely used as a molecular fingerprinting technique, and its use for campylobacters is well documented (11). Although the discriminatory power of PFGE profiling is high, preparation of the DNA-containing blocks is labor intensive, and the apparatus for electrophoresis is likely to be restricted to research and reference laboratories. The Pulsenet (10) method for PFGE gives a turnaround time equal to that of SAFLP, but the amount of hands-on operator time is far greater for PFGE. SAFLP is far less labor intensive than PFGE profiling, involves a single PCR procedure, and uses increasingly widely available technology.

For more detailed investigations, fluorescent AFLP (FAFLP) with two restriction enzymes and fluorescently labeled primers enables detection of many fragments that may be subsequently analyzed on automated DNA sequencers (7). However, in terms of availability and cost of equipment, complexity of data and subsequent ease of analysis, SAFLP is likely to prove more widely applicable.

This study was designed to evaluate both discrimination and ease of use of PFGE and SAFLP, and we conclude that these methods have approximately equal utility. However, SAFLP is less labor intensive and requires less specialized equipment. Standardized procedures for PFGE as developed for Campynet in Europe (www.svs.dk/campynet) and Pulsenet in the United States (10) will improve comparison between laboratories. Such protocols have yet to be developed for SAFLP, but the advantages in terms of turnaround, ease of use, and availability of equipment make this technique an attractive alternative to PFGE for epidemiological investigations.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the help of the staff at the Campylobacter Reference Unit, CPHL, Cardiff Public Health Laboratory, Gill Richardson of CDSC Wales, and Henry Smith for reading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Frost, J. A., J. M. Kramer, and S. A. Gillanders. 1999. Phage typing of C. jejuni and C. coli and its use as an adjunct to serotyping. Epidemiol. Infect. 123:47-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frost, J. A., A. N. Oza, R. T. Thwaites, and B. Rowe. 1998. Serotyping scheme for Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli based on direct agglutination of heat-stable antigens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:335-339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibson, J. R., C. Fitzgerald, and R. J. Owen. 1995. Comparison of PFGE, ribotyping and phage typing in epidemiological analysis of Campylobacter jejuni serotype HS2 infections. Epidemiol. Infect. 115:215-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gibson, J. R., E. Slater, J. Xerry, D. S. Tompkins, and R. J. Owen. 1998. Use of amplified-fragment length polymorphism technique to fingerprint and differentiate isolates of Helicobacter pylori. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2580-2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hänninen, M., S. Pajarre, M.-L. Klossner, and H. Rautelin. 1998. Typing of human Campylobacter jejuni isolates in Finland by pulsed field gel electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1787-1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lorenz, E., A. Lastovica, and R. J. Owen. 1998. Penner serotypes 9, 38 and 63, from human infections, animals and water by PFGE and flagellin gene analysis. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 26:179-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mortimer, P., and C. Arnold. 2001. FAFLP: last word in microbial genotyping. J. Med. Microbiol. 50:393-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nair, S., E. Schreiber, K.-L. Thong, T. Pang, and W. Altwegg. 2000. Genotypic characterisation of Salmonella typhi by amplified fragment length polymorphism fingerprinting provides increased discrimination as compared to pulsed field gel electrophoresis and ribotyping. J. Microbiol. Methods 41:43-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olsen, S. J., G. R. Hansen, L. Bartlett, C. Fitzgerald, A. Sonder, R. Manjrekar, T. Riggs, J. Kim, R. Flahart, G. Pezzino, and D. L. Swerdlow. 2001. An outbreak of Campylobacter jejuni infections associated with food handler contamination: the use of pulsed field gel electrophoresis. J. Infect. Dis. 183:164-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ribot, E. M., C. Fitzgerald, K. Kubota, B. Swaminathan, and T. J. Barrett. 2001. Rapid pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocol for subtyping of Campylobacter jejuni. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1889-1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wassenaar, T. M., and D. G. Newell. 2000. Genotyping of Campylobacter spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson, K., F. M. Ausubel, R. Brent, and R. E. Kingston. 1987. Preparation of genomic DNA from bacteria, p. 2.4.1-2.4.2. In Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley and Sons, New York, N.Y. [DOI] [PubMed]