Abstract

Therapeutic options for infections caused by gram-negative organisms expressing plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases are limited because these organisms are usually resistant to all the β-lactam antibiotics, except for cefepime, cefpirome, and the carbapenems. These organisms are a major concern in nosocomial infections and should therefore be monitored in surveillance studies. Six families of plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases have been identified, but no phenotypic test can differentiate among them, a fact which creates problems for surveillance and epidemiology studies. This report describes the development of a multiplex PCR for the purpose of identifying family-specific AmpC β-lactamase genes within gram-negative pathogens. The PCR uses six sets of ampC-specific primers resulting in amplicons that range from 190 bp to 520 bp and that are easily distinguished by gel electrophoresis. ampC multiplex PCR differentiated the six plasmid-mediated ampC-specific families in organisms such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Family-specific primers did not amplify genes from the other families of ampC genes. Furthermore, this PCR-based assay differentiated multiple genes within one reaction. In addition, WAVE technology, a high-pressure liquid chromatography-based separation system, was used as a way of decreasing analysis time and increasing the sensitivity of multiple-gene assays. In conclusion, a multiplex PCR technique was developed for identifying family-specific ampC genes responsible for AmpC β-lactamase expression in organisms with or without a chromosomal AmpC β-lactamase gene.

Organisms overexpressing AmpC β-lactamases are a major clinical concern because these organisms are usually resistant to all the β-lactam drugs, except for cefepime, cefpirome, and the carbapenems (14, 37). Constitutive overexpression of AmpC β-lactamases in gram-negative organisms occurs either by deregulation of the ampC chromosomal gene or by acquisition of a transferable ampC gene on a plasmid or other transferable element. The transferable ampC gene products are commonly called plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases (2, 6, 37). Organisms that constitutively overexpress the chromosomal genes are collectively called derepressed mutants (16).

The majority of plasmid-mediated ampC genes are found in nosocomial isolates of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae (1, 3-5, 10, 11, 15, 19, 21, 25, 27, 38). However, these enzymes have also been detected in strains of other genera of the family Enterobacteriaceae (11, 40-42). Plasmid-mediated ampC genes are derived from the chromosomal ampC genes of several members of the family Enterobacteriaceae, including Enterobacter cloacae, Citrobacter freundii, Morganella morganii, and Hafnia alvei (2). However, not all members of the family Enterobacteriaceae carry a gene for AmpC β-lactamase or are the origins of plasmid-mediated genes. For example, the chromosomal ampC genes of Enterobacter aerogenes, Serratia marcescens, indole-positive Proteus spp., and E. coli have thus far not been identified in plasmids (2). One important difference between E. coli and the other members of the family Enterobacteriaceae possessing chromosomal ampC is that the expression of ampC in E. coli is not inducible (18). Nevertheless, some E. coli strains (i.e., hyperproducers) can still constitutively overexpress ampC (8, 20, 24). In contrast, K. pneumoniae does not possess chromosomal ampC (2, 26). Therefore, detection of plasmid-mediated ampC in K. pneumoniae is straightforward. However, the distinction between a plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase and an endogenous enzyme becomes almost impossible in both hyperproducing E. coli strains and organisms with inducible chromosomal AmpC enzymes. However, this distinction is critical for surveillance, epidemiology studies, and hospital infection control because plasmid-mediated genes, whether encoding extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) or AmpC enzymes, can spread to other organisms within the hospital setting (11). In addition, multiple β-lactamases within one organism (e.g., multiple ESBLs or ESBL-AmpC combinations) can make phenotypic identification of the β-lactamases difficult (34). Unfortunately, for these reasons, plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase resistance goes undetected in most clinical laboratories (34).

Differentiation of organisms expressing ESBLs from organisms expressing plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases is necessary in order to address surveillance and epidemiology as well as hospital infection control issues associated with these resistance mechanisms. Several phenotypic tests can distinguish these two resistance mechanisms but are unable to differentiate the different types or families of plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases (35, 36). In addition, the use of automated systems, while adequate for less complicated organisms, is not adequate for the newer generation of antibiotic-resistant pathogens that express multiple resistance mechanisms and produce multiple β-lactamases (17, 31-33).

Twenty-nine different plasmid-mediated ampC genes have been identified to date and have been deposited in GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Entrez/). None of the encoded enzymes can be distinguished from another by phenotypic testing. We report here the development of a multiplex PCR for the detection of family-specific plasmid-mediated ampC β-lactamase genes. This technique is capable of identifying the family-specific ampC gene responsible for AmpC β-lactamase expression. In addition, this method can be used to detect a plasmid-mediated ampC gene in organisms expressing a chromosomal AmpC β-lactamase as long as the plasmid-mediated ampC gene is not from the same chromosomal origin. Finally, WAVE technology is introduced as a means of shortening the amount of time required for analysis and increasing the sensitivity of the assay.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The bacterial strains used as controls in this study are listed in Table 1. Strains previously characterized for the expression of specific plasmid-mediated ampC genes are listed in the plasmid group. Strains used as controls to examine the extent of cross-hybridization of specific primers with chromosomal ampC genes are listed in the chromosomal group. One exception was H. alvei strain JW3. The gene for this ampC β-lactamase is chromosomal. No strains harboring the ACC-1 gene or the chromosomal gene from H. alvei strain 1 (ACC-2 gene) were available. However, the genetic similarity between the ACC-1 gene and the chromosomal genes from H. alvei allowed the use of H. alvei JW3 in this study (12, 13). Twenty-two clinical strains belonging to members of the family Enterobacteriaceae phenotypically characterized as putative AmpC producers were evaluated by ampC multiplex PCR for the presence of plasmid-mediated ampC genes. Putative AmpC β-lactamase identifications were conducted by appropriate biochemical procedures, such as isoelectric focusing and substrate and inhibitor profiling (36). These strains were classified as unknown for AmpC type and included 12 strains of E. coli, 8 strains of K. pneumoniae, 1 strain of Proteus mirabilis, and 1 strain of E. aerogenes.

TABLE 1.

Control strains

| Group | Strain | Organism | AmpCa | Reference or sourceb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid mediated | MISC 340 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | FOX-1 | 15 |

| MISC 393 | Escherichia coli | FOX-3 | 21 | |

| MISC 416 | Escherichia coli | FOX-4 | 4 | |

| MHM 2 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | FOX-5c | 27 | |

| COUD M 621 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | FOX-5bc | GenBank accession no. AY034843 | |

| MISC 341 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | LAT-1 | 38 | |

| MISC 368 | Escherichia coli | LAT-2 | 11 | |

| KLEB 249 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | CMY-2c | 3 | |

| SAL 100 | Salmonella typhimurium | CMY-7c | GenBank accession no. AJ011291 | |

| MISC 345 | Escherichia coli | BIL-1 | 10 | |

| MISC 339 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | MOX-1 | 19 | |

| MISC 380 | Escherichia coli | DHA-1 | 1 | |

| MISC 304 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | MIR-1 | 25 | |

| KLEB 225 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | ACT-1c | 5 | |

| Chromosomal | JW3 | Hafnia alvei | WT | PC |

| ENTB 7 | Enterobacter cloacae | WT | SEQ | |

| GB 52 | Citrobacter spp. | DR | PC | |

| 21 | Citrobacter freundii | WT | SEQ | |

| 316 | Citrobacter freundii | WT | PC | |

| VA 076 | Citrobacter freundii | WT | PC | |

| CA 113 | Citrobacter freundii | WT | PC | |

| CIN 6 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | WT | SEQ | |

| SERR 1 | Serratia marcescens | WT | SEQ | |

| MORG 103 | Morganella morganii | WT | PC | |

| HB101 | Escherichia coli | WT | PC | |

| KLEB 23 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | WT | PC | |

| VITEK 109492 | Escherichia coli | HYP | PC | |

| P2 | Proteus mirabilis | WT | PC | |

| EAE | Enterobacter aerogenes | WT | PC |

WT, wild type; DR, derepressed mutant; HYP, hyperproducing mutant.

PC, phenotypically characterized in this study; SEQ, sequenced in the Hanson Laboratory.

Sequenced in the Hanson laboratory.

Preparation of template DNA.

A single colony of each organism was inoculated from a blood agar plate into 5 ml of Luria-Bertani broth (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) and incubated for 20 h at 37°C with shaking. Cells from 1.5 ml of the overnight culture were harvested by centrifugation at 17,310 × g for 5 min. After the supernatant was decanted, the pellet was resuspended in 500 μl of distilled water. The cells were lysed by heating at 95°C for 10 min, and cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 17,310 × g for 5 min. The supernatant, 2 μl (1/250 volume) of the total sample, was used as the source of template for amplification.

PCR protocol.

PCR was performed with a final volume of 50 μl in 0.5-ml thin-walled tubes. The primers used for PCR amplification are listed in Table 2. Each reaction contained 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.4); 50 mM KCl; 0.2 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate; 1.5 mM MgCl2; 0.6 μM primers MOXMF, MOXMR, CITMF, CITMR, DHAMF, and DHAMR; 0.5 μM primers ACCMF, ACCMR, EBCMF, and EBCMR; 0.4 μM primers FOXMF and FOXMR; and 1.25 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Life Technologies, Rockville, Md.). Template DNA (2 μl) was added to 48 μl of the master mixture and then overlaid with mineral oil. The PCR program consisted of an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 3 min, followed by 25 cycles of DNA denaturation at 94°C for 30s, primer annealing at 64°C for 30s, and primer extension at 72°C for 1 min. After the last cycle, a final extension step at 72°C for 7 min was added. Five-microliter aliquots of PCR product were analyzed by gel electrophoresis with 2% agarose (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). Gels were stained with ethidium bromide at 10 μg/ml and visualized by UV transillumination. A 100-bp DNA ladder from Life Technologies was used as a marker. Negative controls were PCR mixtures with the addition of water in place of template DNA. In some cases, negative controls were used prior to the addition of any other templates (tube 1) and for the carryover of a template when multiple templates were being used in one experiment (last tube).

TABLE 2.

Primers used for amplification

| Target(s) | Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3 ′, as synthesized) | Expected amplicon size (bp) | Nucleotide positions | GenBank accession no.a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOX-1, MOX-2, CMY-1, CMY-8 to CMY-11 | MOXMF | GCT GCT CAA GGA GCA CAG GAT | 520 | 358-378 | D13304 |

| MOXMR | CAC ATT GAC ATA GGT GTG GTG C | 877-856 | |||

| LAT-1 to LAT-4, CMY-2 to CMY-7, BIL-1 | CITMF | TGG CCA GAA CTG ACA GGC AAA | 462 | 478-498 | X78117 |

| CITMR | TTT CTC CTG AAC GTG GCT GGC | 939-919 | |||

| DHA-1, DHA-2 | DHAMF | AAC TTT CAC AGG TGT GCT GGG T | 405 | 1244-1265 | Y16410 |

| DHAMR | CCG TAC GCA TAC TGG CTT TGC | 1648-1628 | |||

| ACC | ACCMF | AAC AGC CTC AGC AGC CGG TTA | 346 | 861-881 | AJ133121 |

| ACCMR | TTC GCC GCA ATC ATC CCT AGC | 1206-1186 | |||

| MIR-1T ACT-1 | EBCMF | TCG GTA AAG CCG ATG TTG CGG | 302 | 1115-1135 | M37839 |

| EBCMR | CTT CCA CTG CGG CTG CCA GTT | 1416-1396 | |||

| FOX-1 to FOX-5b | FOXMF | AAC ATG GGG TAT CAG GGA GAT G | 190 | 1475-1496 | X77455 |

| FOXMR | CAA AGC GCG TAA CCG GAT TGG | 1664-1644 |

Sequence used for primer design.

Sequence analysis of a CIT-like PCR amplicon.

The full-length PCR amplicon used for sequence analysis was generated with primers designed to flank the entire gene for CMY-2 (GenBank accession number X91840), a plasmid-mediated ampC gene of C. freundii origin: forward primer, located at bp 1861 to 1881, 5′-AACACACTGATTGCGTCTGAC-3′, and reverse primer, located at bp 3086 to 3067, 5′-CTGGGCCTCATCGTCAGTTA-3′. The PCR was performed as described above, except for the use of 5 μM primers and an annealing temperature of 60°C. The 1,226-bp PCR amplicon was treated with ExoSAP-IT as directed by the manufacturer (USB Corp., Cleveland, Ohio) to remove unwanted nucleotides and was sequenced directly by automated PCR cycle sequencing with dye-terminator chemistry and a DNA Stretch sequencer from Applied Biosystems. The primers used for sequencing were the primers used to generate the amplicon and internal primers specific for the C. freundii ampC gene.

WAVE analysis of ampC multiplex PCR.

Following PCR amplification, the products were analyzed by using the WAVE DNA fragment analysis system with Wavemaker Software (Transgenomic, Inc., Omaha, Nebr.). Samples were loaded onto the autosampler, and 5 μl of each sample was injected individually onto a DNASep column (Transgenomic). The optimized gradient for the separation of PCR products is shown in Table 3. The buffers used for the gradient were as follows: A, 0.1 M triethylammonium acetate (Transgenomic); B, 0.1 M triethylammonium acetate-25% acetonitrile; and D, 75% acetonitrile. All samples were analyzed at 50°C with a 0.9-ml/min flow rate.

TABLE 3.

WAVE gradient parameters

| Stepa | Time (min)b | % Buffer

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | D | ||

| Loading | 0.0 | 51 | 49 | 0 |

| Step 1 | 0.5 | 46 | 54 | 0 |

| Step 2 | 1.0 | 42 | 58 | 0 |

| Step 3 | 1.5 | 40 | 60 | 0 |

| Step 4 | 2.5 | 38 | 62 | 0 |

| Step 5 | 3.5 | 37 | 63 | 0 |

| Step 6 | 4.5 | 37 | 63 | 0 |

| Step 7 | 5.5 | 34 | 66 | 0 |

| Step 8 | 6.5 | 32 | 68 | 0 |

| Start clean | 6.6 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Stop clean | 7.1 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Start equilibrate | 7.2 | 51 | 49 | 0 |

| Stop equilibrate | 8.1 | 51 | 49 | 0 |

Sequence of events for loading the column, gradient changes, and cleaning the column.

Time of each gradient change.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank nucleotide sequence accession numbers for the sequences studied here were as follows: CMY-2 (X91840), FOX-2 (Y10282), FOX-1 (X77455), FOX-4 (AJ277535), ACT-1 (U58495), MIR-1 (M37839), MOX-1 (D13304), DHA-1 (AJ237702), DHA-2 (AF259520), LAT-1 (X78117), CMY-1 (X92508), CMY-4 (AJ007826), BIL-1 (X74512), LAT-2 (S83226), ACC-1 (AJ270941), ACC-2 (AF180952), FOX-3 (Y11068), FOX-5 (AY007369), FOX-5b (FOX-6; see Results) (AY034848), CMY-10 (AF381618), CMY-11 (AF381626), CMY-8 (AF167990), CMY-9 (AB061794), MOX-2 (AJ276453), LAT-3 (Y15411), CMY-3 (Y16783), CMY-6 (AJ011293), CMY-7 (AJ011291), CMY-5 (Y17716), and LAT-4 (Y15412).

RESULTS

Dendrogram and primer design.

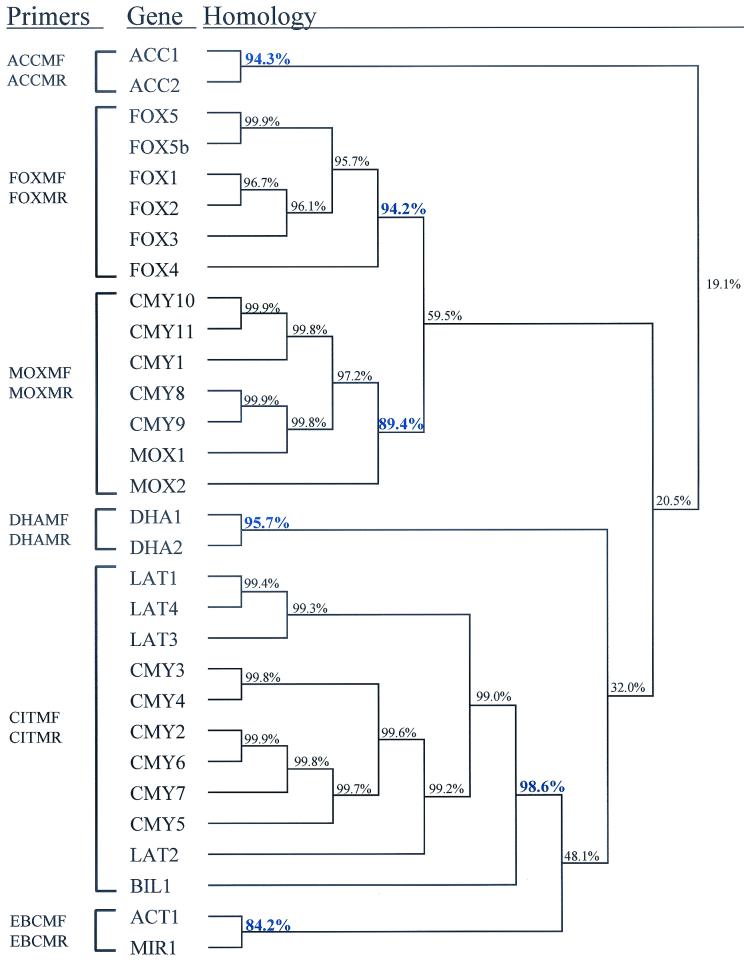

The genes encoding plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases are of chromosomal origin, derived from members of the family Enterobacteriaceae. To date, 29 different genes encoding 28 different plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases have been identified (Fig. 1). They can be grouped based on their chromosomal origins. For example, the genes encoding the AmpC β-lactamases LAT-1, CMY-2, and BIL-1 are 90.4% similar to the chromosomal ampC gene of C. freundii strain OS60. The ability to group different ampC genes allows the evaluation of similarity clusters. A high degree of similarity within these clusters can result in a primer design capable of amplifying family-specific genes. Twenty-nine plasmid-mediated gene sequences and one chromosomal gene (ACC-2) sequence were downloaded from the GenBank database, and percent similarities were analyzed by using DNAsis for Windows, version 2.6 (Hitachi Software) (Fig. 1). The accession numbers for these sequences are listed in Materials and Methods.

FIG. 1.

AmpC dendrogram. Sequences were downloaded from the GenBank database, and structural genes were compared, as described in Material and Methods, by using the DNAsis program. Values in blue correspond to the percent similarity between the most distinct member of each cluster and the other members within that cluster. Primer pairs are correlated by the family of genes that they amplify.

Six different groups were identified based on percent similarities. These groups include ACC (origin H. alvei), FOX (origin unknown), MOX (origin unknown), DHA (origin M. morganii), CIT (origin C. freundii), and EBC (origin E. cloacae). The percent similarities among the family members within these clustered groups were 94.3, 94.2, 89.4, 95.7, 98.6, and 84.2% for the ACC, FOX, MOX, DHA, CIT, and EBC groups, respectively. The blaFOX-5b gene, previously reported as blaFOX-6 (GenBank accession number AY034848), differs in only 1 nucleotide from and codes for the same enzyme as FOX-5. This gene serves as a genetic variant of the same gene in the analysis.

The sequences of each cluster were aligned with the CLUSTAL W multiple-alignment option in the MacVector, version 6.5, program (Oxford Molecular Ltd.), and the aligned sequences were used as a reference for primer design. The resulting primers were compared with all members of the different clusters in order to avoid cross-hybridization. In addition, primers were evaluated for individual melting temperatures and lengths. Variations between the individual primers allowed a change in melting temperature of 0.5°C and a difference in length of 2 nucleotides. The theoretical formation of primer dimers was also evaluated and found insignificant. The 12 primers designed for multiplex PCR are listed in Table 2 and in Fig. 1.

Initial analysis of ampC multiplex PCR.

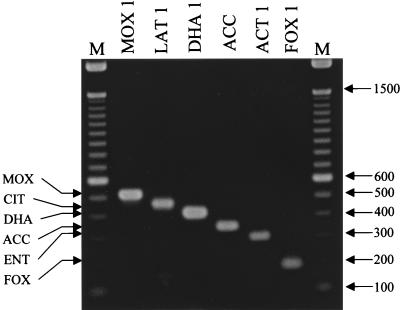

The compatibility of the six primer pairs was tested by using the conditions described in Materials and Methods. Each reaction shown in Fig. 2 contained six primer sets and template DNA from a representative member of each of the ampC groups previously described: blaMOX-1, blaLAT-1, blaDHA-1, blaACC, blaACT-1, and blaFOX-1 (1, 5, 12-15, 19, 38). The template used for ACC represents the chromosomal ampC gene from H. alvei JW3 but is not specifically ACC-2. Only one amplification product was observed for each template, and the size observed was consistent with the expected size shown in Table 2. Individual primer pairs (for example, FOXMF and FOXMR) were evaluated by using template DNA from the same representative members as those used above to ensure that one primer pair amplified only one amplicon. Amplification was observed only when each set of family-specific primers was used with template DNA from that particular ampC family. Using these parameters, only one amplicon of the predicted size was observed for each template-primer pair tested (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Initial analysis of ampC multiplex PCR. Multiplex PCR products were separated in a 2% agarose gel. Lanes are labeled with the ampC gene used as template DNA; ACC, chromosomal ampC gene from H. alvei; M, 100-bp DNA ladder. The amplified product from each PCR is indicated on the left, and the size of the marker in base pairs is shown on the right.

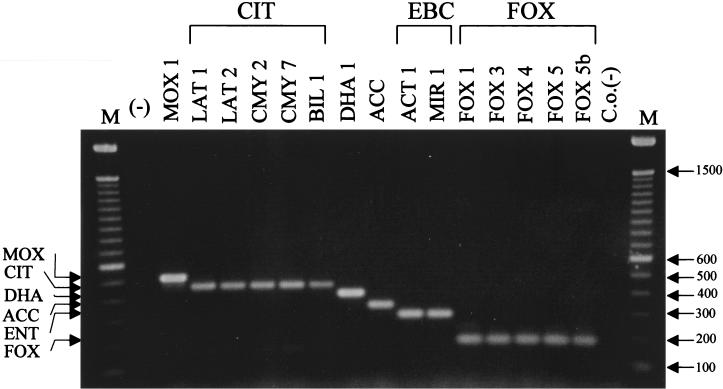

Impact of family-specific variations on multiplex amplification.

Sequences of ampC genes from the same family show slight variations (genetic changes). These variations can lead to an amino acid substitution(s) resulting in the individual family member. For example, sequences of members of the proposed Citrobacter-originating family have a group similarity of 98.6% (Fig. 1). In order to demonstrate that sequence variations of individual family members would not influence the outcome of ampC multiplex PCR, different members of representative families (Table 1) were used as templates (Fig. 3). The amplification of products for each family member of a particular set (CIT, EBC, and FOX) resulted in a single amplicon of the predicted size. For example, every template of the CIT family resulted in an amplicon of 462 bp (Fig. 3). In addition, single amplicons of 302 and 190 bp were generated for the EBC family members MIR-1 and ACT-1 and for the FOX family members FOX-1 to FOX-5b, respectively.

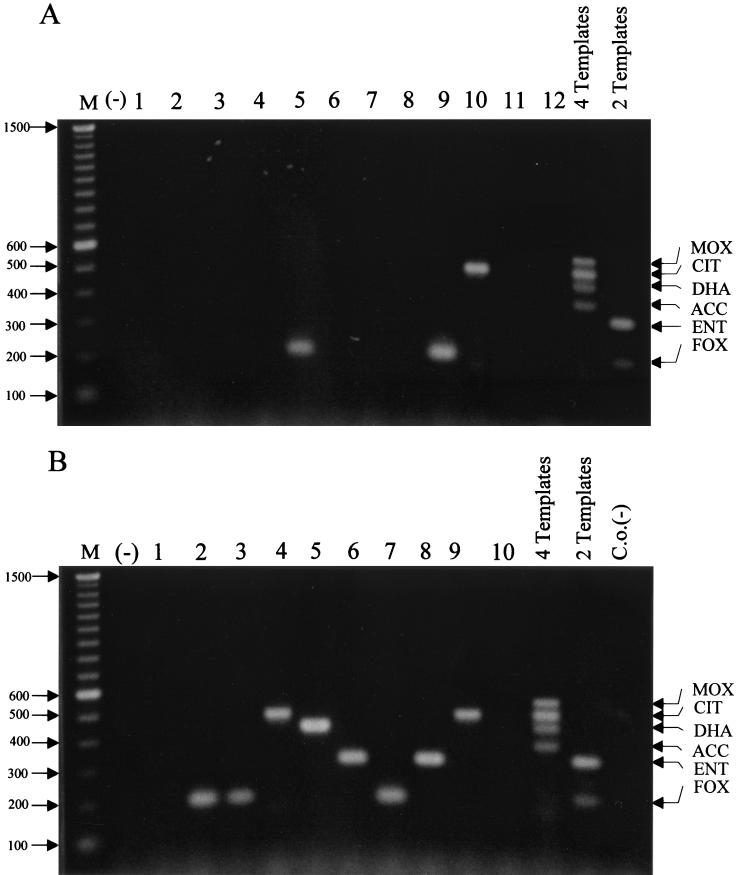

FIG. 3.

Resolution of family-specific variation. Multiplex PCR products were separated in a 2% agarose gel. Lanes are labeled with the ampC gene used as template DNA; ACC, chromosomal ampC gene from H. alvei; M, 100-bp DNA ladder; (−), negative water control; C.o.(−), carryover negative control. The amplified product from each PCR is indicated on the left, and the size of the marker in base pairs is shown on the right.

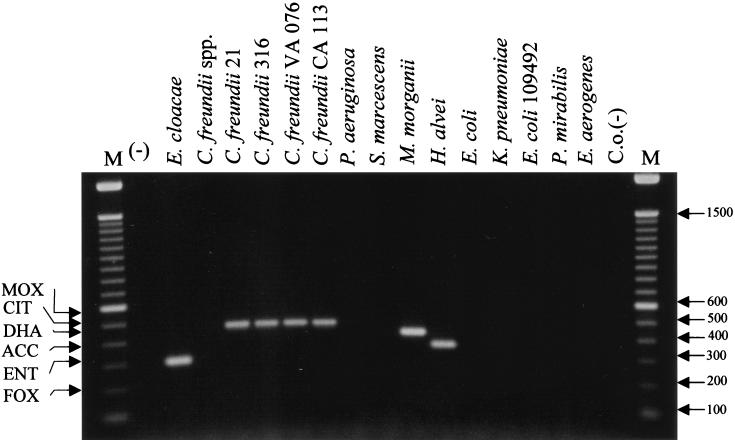

Evaluation of chromosomal cross-hybridization.

The mobility of plasmid-mediated ampC β-lactamases requires that any molecular technique used for identification of the gene be functional for different gram-negative organisms, including organisms with chromosomal ampC genes, such as E. cloacae and C. freundii (16). Because plasmid-mediated ampC genes originated from chromosomal genes, the ampC multiplex PCR was tested for the possibility of cross-hybridization with chromosomal β-lactamase genes of different origins. Multiplex PCR was conducted with the organisms listed in the chromosomal group in Table 1. No amplification was observed when a DNA template from K. pneumoniae, E. coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, S. marcescens, P. mirabilis, or E. aerogenes was used (Fig. 4). As expected, an amplification product of the Enterobacter-originating ampC gene was obtained when DNA from E. cloacae was used as a template (Fig. 4). This band represents the EBC product of 302 bp (Table 2), but no other set of ampC-specific primers cross-reacted with this chromosomal DNA. In addition, products of the expected sizes for Citrobacter-, Morganella-, and Hafnia-originating ampC genes were observed when DNAs from C. freundii, M. morganii, and H. alvei were used as templates. In addition, a DNA template prepared from a Citrobacter sp. other than C. freundii did not result in an amplified product, indicating the specificity of the primer pair.

FIG. 4.

Evaluation of chromosomal cross-hybridization. Multiplex PCR products were separated in a 2% agarose gel. Lanes are labeled with the name of the organism used as the source of template DNA (Table 1); M, 100-bp DNA ladder; (−), negative water control; C.o.(−), carryover negative control. The amplified product from each PCR is indicated on the left, and the size of the marker in base pairs is shown on the right.

Analysis of putative AmpC-producing clinical isolates.

The data presented in Fig. 2 to 4 substantiate the specificity of the ampC multiplex PCR with highly characterized strains (both phenotypically and molecularly). However, verification of the multiplex PCR-based assay requires the use of isolates not previously characterized by molecular methods. Therefore, DNAs from 22 AmpC-producing isolates, as determined by phenotypic characterization, were analyzed by ampC multiplex PCR (Fig. 5). Two multiple-template PCRs with two known control templates (ACT-1 and FOX-1) or four known control templates (MOX-1, LAT-1, DHA-1, and ACC) were performed, and the products were separated in the same gel to serve as markers for individual unknown reactions. PCR analysis indicated no amplification from DNA templates prepared from 11 isolates (Fig. 5A, lanes 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 11, and 12, and Fig. 5B, lanes 1 and 10). A single product was amplified with DNA templates prepared from the other 11 isolates. An amplification product of ca. 200 bp (FOX-like) was observed with DNA prepared from five isolates (Fig. 5A, lanes 5 and 9, and Fig. 5B, lanes 2, 3, and 7). An amplicon of ca. 300 bp (Enterobacter-like) was observed with DNA prepared from two isolates (Fig. 5B, lanes 6 and 8). An amplicon of ca. 400 bp (DHA-like) was observed from DNA prepared from one isolate (Fig. 5B, lane 5). An amplicon of ca. 460 bp (Citrobacter-like) was generated from DNA prepared from three isolates (Fig. 5A, lane 10, and Fig. 5B, lanes 4 and 9). As an example, the amplicon generated from the E. coli isolate (Fig. 5A, lane 10) was sequenced to verify that the amplicons generated from unknown isolates were as predicted. The CIT-like amplicon in the ampC multiplex PCR (Fig. 5A, lane 10) was confirmed to be blaCMY-2, a Citrobacter-originating plasmid-mediated ampC gene, by amplifying the entire structural gene and sequencing the full-length amplicon.

FIG. 5.

Analysis of clinical isolates. Multiplex PCR products were separated in a 2% agarose gel. M, 100-bp DNA ladder; (−), negative water control; 4 Templates, MOX-1, LAT-1, DHA-1, and ACC; 2 Templates, FOX-1 and ACT-1; C.o.(−), carryover negative control. (A) Lanes 1 to 4, 6 to 8, and 12, E. coli isolates; lanes 5 and 9, K. pneumoniae isolates; lane 10, P. mirabilis isolate; lane 11, E. aerogenes isolate. (B) Lanes 1, 2, 4, and 10, E. coli isolates; lanes 3 and 5 to 9, K. pneumoniae isolates. The amplified product from each PCR is indicated on the right, and the size of the marker in base pairs is shown on the left.

WAVE analysis.

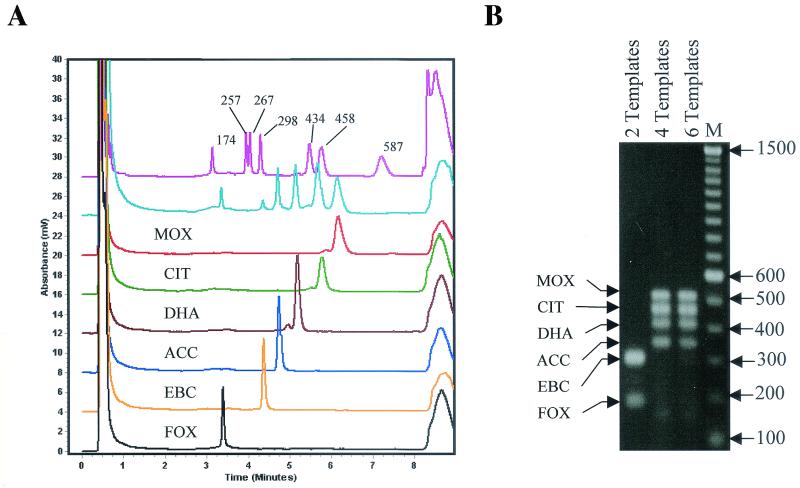

In order to reduce the total required analytical time without losing specificity or sensitivity, a high-pressure liquid chromatography-based nucleic acid analysis technology, the WAVE DNA fragment analysis system, was used. A comparison of gel electrophoresis and WAVE technology was performed by using ampC multiplex PCR products from a representative member of each gene family (Fig. 2). The amplified products visualized by gel electrophoresis in Fig. 2, MOX-1 (520 bp), LAT-1 (CIT family) (462 bp), DHA-1 (405 bp), ACC (346 bp), ACT-1 (EBC family) (302 bp), and FOX-1 (190 bp), correlate with the peaks observed in Fig. 6A, with retention times of 6.07 min (red line), 5.78 min (green line), 5.19 min (brown line), 4.76 min (blue line), 4.39 min (orange line), and 3.41 min (black line), respectively. The initial peak at 0.5 min and the final peak at 10 min in Fig. 6A correspond to injection and washoff peaks, respectively.

FIG. 6.

WAVE analysis. (A) Chromatogram obtained by using multiplex PCR products amplified from the following DNA templates (bottom to top): FOX-1, ACT-1, ACC, DHA-1, LAT-1, MOX-1, combination of the six DNA templates listed above, and DNA marker pUC18. (B) Agarose gel electrophoresis of multiplex PCR products obtained by using three different combinations of DNA templates: 2 Templates, FOX-1 and ACT-1; 4 Templates, MOX-1, LAT-1, DHA-1, and ACC; and 6 Templates, combination of the six templates listed above. M, 100-bp ladder.The amplified product from each PCR is indicated on the left, and the size of the marker in base pairs is shown on the right.

Multiple templates, i.e., two (FOX-1 and ACT-1), four (MOX-1, LAT-1, DHA-1, and ACC), or six (a combination of the two templates and the four templates just listed), were mixed and amplified by using ampC multiplex PCR. PCR amplification of two or four templates resulted in amplicons of the expected sizes that were easily visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining, as shown in Fig. 6B. However, visualization of all six amplified products in one reaction was not possible. A sample that was obtained from the same PCR which generated the six amplification products and that was analyzed by gel electrophoresis was subjected to WAVE analysis. All six products were observed as well-defined peaks (Fig. 6A, aqua line). Each peak had a retention time equivalent to the retention time observed in the single-template amplification, and each peak was consistent with the size and retention time expected relative to the pUC18 size standard (Fig. 6A, pink line) and the individual peaks described above.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of AmpC-mediated resistance in the United States and worldwide is unknown, due in part to the limited number of surveillance studies seeking clinical strains producing AmpC β-lactamases and the difficulty that laboratories have in accurately detecting this resistance mechanism (34). Reducing the spread of plasmid-mediated AmpC resistance in hospitals requires the identification of the genes involved in order to control the movement of this resistance mechanism. Clinical laboratories interested in distinguishing AmpC-mediated resistance from other β-lactamase resistance mechanisms will need to use molecular identification methods. The multiplex PCR technique described in this report will be an important tool for the detection of transferable (i.e., plasmid-mediated) ampC β-lactamase genes in gram-negative bacteria.

Conventional phenotypic methods used to detect isolates expressing AmpC β-lactamases have restricted the detection of this resistance mechanism to mainly organisms without an inducible chromosomal ampC gene, such as K. pneumoniae, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, or E. coli (1, 4, 9-11, 16, 19, 25). In K. pneumoniae and Salmonella serovar Typhimurium, no chromosomal gene is present. Therefore, no endogenous AmpC β-lactamase can interfere with either susceptibility testing or hydrolysis assays (23, 26). Since E. coli produces its chromosomal ampC gene at a low constitutive level, the endogenous enzyme has little influence on susceptibility testing or β-lactamase hydrolysis assays (30). However, molecular analysis will be required to verify the presence of transferable ampC genes in hyperproducing E. coli or gram-negative pathogens coding for inducible chromosomal AmpC β-lactamases.

This study demonstrated the use of multiplex PCR for distinguishing family-specific ampC genes in various gram-negative organisms, including K. pneumoniae, E. coli, P. mirabilis, and Salmonella serovar Typhimurium. When DNA prepared from E. coli isolates resulted in no amplified products, we concluded that these isolates were most likely hyperproducers of the chromosomal ampC gene (Fig. 5). This conclusion was based on the absence of a PCR amplicon together with susceptibility and isoelectric focusing characterizations (data not shown). In this regard, ampC multiplex PCR demonstrated further discriminatory power, distinguishing between the presence of known transferable ampC genes and suspected hyperproducing E. coli isolates. In addition, ampC multiplex PCR also discriminated between transferable ampC genes coding for inducible AmpC β-lactamases as long as they were not of the same origin (Fig. 4).

Clinical isolates expressing more than one plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase have not been reported. Two reasons could explain this observation. First, the inability to accurately detect the type of transferable AmpC β-lactamase does not allow for the differentiation of multiple AmpC enzymes. Second, it is possible that there is a limit to the amount of AmpC β-lactamase that a bacterial cell can accommodate and still be a viable pathogen (23). Thus, organisms may not be able to express two or more plasmid-mediated ampC genes. However, if multiple plasmid-mediated ampC genes can be expressed in a single organism, then the ampC multiplex PCR technique described in this report can be used to differentiate them. This application was demonstrated by the identification of two, four, or six amplicons when multiple template DNAs prepared from bacterial isolates were added to one PCR.

Specificity and sensitivity are important criteria used to evaluate diagnostic techniques. In clinical laboratories, speed is also an important parameter. The time required to prepare template DNA and perform multiplex PCR in this study was 1.5 h. However, visualization of the PCR products by gel electrophoresis required approximately 4 h for high resolution of bands in 2% agarose, staining, destaining, and interpretation of data. WAVE analysis was able to decrease the time required for results from 5.5 h to less than 2 h. In addition, WAVE analysis was able to detect six amplicons within one multiplex PCR sample, whereas electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining could only accurately detect four different genes at a time. Therefore, techniques such as WAVE analysis can be beneficial not only as time-saving devices but also by increasing the sensitivity of molecular assays.

The mechanism(s) by which pathogenic organisms become resistant to antimicrobial agents is becoming increasingly complex. A single type of test, whether based on phenotypic or molecular analysis, will not be able to accurately characterize the resistance mechanisms in these complex organisms. All laboratory tests have limitations. Although automated systems are available for susceptibility testing, the accuracy of these phenotypic tests are not adequate for organisms expressing plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases alone or in combinations with ESBLs (7, 22, 28, 29, 39). A primary limitation of automated systems is that detection is based on programmed mathematical algorithms. As the combination of resistance mechanisms found in pathogens becomes more complicated, updating these programs will become more difficult. The limitation of molecular assays is that identification is based on known genes or sequences. Therefore, given the shortcomings of both types of analyses, optimal characterization of resistance mechanisms in complex resistant pathogens will require the use of both molecular and phenotypic analyses. High-throughput systems capable of molecular analysis, such as the WAVE system, are necessary companions for automated phenotypic analysis. Together, these tools can more accurately detect the increasingly complex resistance mechanisms observed in clinical isolates. Increased accuracy in the identification of resistance mechanisms will result in improved surveillance studies, infection control, and available therapeutic options.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ellen Smith Moland and Jennifer Black for expert advice and technical support on the strains used in this study. We also thank Stacey Morrow for expert technical assistance for analyzing the PCR amplicons by WAVE technology, and we thank Transgenomic for the use of WAVE technology. We thank the Center for Research in Anti-Infectives and Biotechnology for continued support in terms of scientific discussion and preview of the manuscript. We also thank Stephen Cavalieri, Philip Lister, and Stacey Morrow for critical review of the manuscript.

We thank the Spanish Government (Ministerio de Educación, Cultura, y Deportes) for a grant supporting F. Javier Pérez-Pérez during his work in the United States at the Center for Research in Anti-Infectives and Biotechnology to complete this project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnaud, G., G. Arlet, C. Verdet, O. Gaillot, P. H. Lagrange, and A. Philippon. 1998. Salmonella enteritidis: AmpC plasmid-mediated inducible beta-lactamase (DHA-1) with an ampR gene from Morganella morganii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2352-2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauernfeind, A., Y. Chong, and K. Lee. 1998. Plasmid-encoded AmpC beta-lactamases: how far have we gone 10 years after the discovery? Yonsei Med. J. 39:520-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauernfeind, A., I. Stemplinger, R. Jungwirth, and H. Giamarellou. 1996. Characterization of the plasmidic beta-lactamase CMY-2, which is responsible for cephamycin resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:221-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bou, G., A. Oliver, M. Ojeda, C. Monzon, and J. Martinez-Beltran. 2000. Molecular characterization of FOX-4, a new AmpC-type plasmid-mediated beta-lactamase from an Escherichia coli strain isolated in Spain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2549-2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradford, P. A., C. Urban, N. Mariano, S. J. Projan, J. J. Rahal, and K. Bush. 1997. Imipenem resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae is associated with the combination of ACT-1, a plasmid-mediated AmpC beta-lactamase, and the loss of an outer membrane protein. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:563-569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bush, K. 2001. New beta-lactamases in Gram-negative bacteria: diversity and impact on the selection of antimicrobial therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32:1085-1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canton, R., M. Perez-Vazquez, A. Oliver, B. Sanchez Del Saz, M. O. Gutierrez, M. Martinez-Ferrer, and F. Baquero. 2000. Evaluation of the Wider system, a new computer-assisted image-processing device for bacterial identification and susceptibility testing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1339-1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caroff, N., E. Espaze, I. Berard, H. Richet, and A. Reynaud. 1999. Mutations in the ampC promoter of Escherichia coli isolates resistant to oxyiminocephalosporins without extended spectrum beta-lactamase production. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 173:459-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fortineau, N., L. Poirel, and P. Nordmann. 2001. Plasmid-mediated and inducible cephalosporinase DHA-2 from Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 47:207-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fosberry, A. P., D. J. Payne, E. J. Lawlor, and J. E. Hodgson. 1994. Cloning and sequence analysis of blaBIL-1, a plasmid-mediated class C beta-lactamase gene in Escherichia coli BS. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:1182-1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gazouli, M., L. S. Tzouvelekis, E. Prinarakis, V. Miriagou, and E. Tzelepi. 1996. Transferable cefoxitin resistance in enterobacteria from Greek hospitals and characterization of a plasmid-mediated group 1 beta-lactamase (LAT-2). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:1736-1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Girlich, D., A. Karim, C. Spicq, and P. Nordmann. 2000. Plasmid-mediated cephalosporinase ACC-1 in clinical isolates of Proteus mirabilis and Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 19:893-895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Girlich, D., T. Naas, S. Bellais, L. Poirel, A. Karim, and P. Nordmann. 2000. Biochemical-genetic characterization and regulation of expression of an ACC-1-like chromosome-borne cephalosporinase from Hafnia alvei. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1470-1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Girlich, D., T. Naas, S. Bellais, L. Poirel, A. Karim, and P. Nordmann. 2000. Heterogeneity of AmpC cephalosporinases of Hafnia alvei clinical isolates expressing inducible or constitutive ceftazidime resistance phenotypes Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3220-3223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez Leiza, M., J. C. Perez-Diaz, J. Ayala, J. M. Casellas, J. Martinez-Beltran, K. Bush, and F. Baquero. 1994. Gene sequence and biochemical characterization of FOX-1 from Klebsiella pneumoniae, a new AmpC-type plasmid-mediated beta-lactamase with two molecular variants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:2150-2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanson, N. D., and C. C. Sanders. 1999. Regulation of inducible AmpC beta-lactamase expression among Enterobacteriaceae. Curr. Pharm. Des. 5:881-894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanson, N. D., K. S. Thomson, E. S. Moland, C. C. Sanders, G. Berthold, and R. G. Penn. 1999. Molecular characterization of a multiply resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae encoding ESBLs and a plasmid-mediated AmpC. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 44:377-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Honore, N., M. H. Nicolas, and S. T. Cole. 1986. Inducible cephalosporinase production in clinical isolates of Enterobacter cloacae is controlled by a regulatory gene that has been deleted from Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 5:3709-3714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horii, T., Y. Arakawa, M. Ohta, T. Sugiyama, R. Wacharotayankun, H. Ito, and N. Kato. 1994. Characterization of a plasmid-borne and constitutively expressed blaMOX-1 gene encoding AmpC-type beta-lactamase. Gene 139:93-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaurin, B., T. Grundstrom, and S. Normark. 1982. Sequence elements determining ampC promoter strength in E. coli. EMBO J. 1:875-881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marchese, A., G. Arlet, G. C. Schito, P. H. Lagrange, and A. Philippon. 1998. Characterization of FOX-3, an AmpC-type plasmid-mediated beta-lactamase from an Italian isolate of Klebsiella oxytoca. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:464-467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moland, E. S., C. C. Sanders, and K. S. Thomson. 1998. Can results obtained with commercially available MicroScan microdilution panels serve as an indicator of beta-lactamase production among Escherichia coli and Klebsiella isolates with hidden resistance to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins and aztreonam? J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2575-2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morosini, M. I., J. A. Ayala, F. Baquero, J. L. Martinez, and J. Blazquez. 2000. Biological cost of AmpC production for Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3137-3143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson, E. C., and B. G. Elisha. 1999. Molecular basis of AmpC hyperproduction in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:957-959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Papanicolaou, G. A., A. A. Medeiros, and G. A. Jacoby. 1990. Novel plasmid-mediated beta-lactamase (MIR-1) conferring resistance to oxyimino- and alpha-methoxy beta-lactams in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34:2200-2209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petit, A., H. Ben-Yaghlane-Bouslama, L. Sofer, and R. Labia. 1992. Characterization of chromosomally encoded penicillinases in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 29:629-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Queenan, A. M., S. Jenkins, and K. Bush. 2001. Cloning and biochemical characterization of FOX-5, an AmpC-type plasmid-encoded beta-lactamase from a New York City Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3189-3194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanders, C. C., M. Peyret, E. S. Moland, S. J. Cavalieri, C. Shubert, K. S. Thomson, J. M. Boeufgras, and W. E. Sanders, Jr. 2001. Potential impact of the VITEK 2 system and the Advanced Expert System on the clinical laboratory of a university-based hospital. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2379-2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanders, C. C., M. Peyret, E. S. Moland, C. Shubert, K. S. Thomson, J. M. Boeufgras, and W. E. Sanders, Jr. 2000. Ability of the VITEK 2 Advanced Expert System to identify beta-lactam phenotypes in isolates of Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:570-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanders, C. C., and W. E. Sanders, Jr. 1992. Beta-lactam resistance in gram-negative bacteria: global trends and clinical impact. Clin. Infect. Dis. 15:824-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen, D., P. Winokur, and R. N. Jones. 2001. Characterization of extended spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae from Beijing, China. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 18:185-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silva, J., R. Gatica, C. Aguilar, Z. Becerra, U. Garza-Ramos, M. Velazquez, G. Miranda, B. Leanos, F. Solorzano, and G. Echaniz. 2001. Outbreak of infection with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Mexican hospital. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3193-3196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steward, C. D., J. K. Rasheed, S. K. Hubert, J. W. Biddle, P. M. Raney, G. J. Anderson, P. P. Williams, K. L. Brittain, A. Oliver, J. E. McGowan, Jr., and F. C. Tenover. 2001. Characterization of clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae from 19 laboratories using the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards extended-spectrum beta-lactamase detection. Methods J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2864-2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomson, K. S. 2001. Controversies about extended-spectrum and AmpC beta-lactamases. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:333-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomson, K. S., and C. C. Sanders. 1992. Detection of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in members of the family Enterobacteriaceae: comparison of the double-disk and three-dimensional tests. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:1877-1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomson, K. S., C. C. Sanders, and J. A. Washington II. 1991. High-level resistance to cefotaxime and ceftazidime in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from Cleveland, Ohio. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:1001-1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomson, K. S., and E. Smith Moland. 2000. Version 2000: the new beta-lactamases of Gram-negative bacteria at the dawn of the new millennium. Microbes Infect. 2:1225-1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tzouvelekis, L. S., E. Tzelepi, and A. F. Mentis. 1994. Nucleotide sequence of a plasmid-mediated cephalosporinase gene (blaLAT-1) found in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:2207-2209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tzouvelekis, L. S., A. C. Vatopoulos, G. Katsanis, and E. Tzelepi. 1999. Rare case of failure by an automated system to detect extended-spectrum beta-lactamase in a cephalosporin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2388.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verdet, C., G. Arlet, G. Barnaud, P. H. Lagrange, and A. Philippon. 2000. A novel integron in Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis, carrying the bla(DHA-1) gene and its regulator gene ampR, originated from Morganella morganii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:222-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verdet, C., G. Arlet, S. Ben Redjeb, A. Ben Hassen, P. H. Lagrange, and A. Philippon. 1998. Characterisation of CMY-4, an AmpC-type plasmid-mediated beta-lactamase in a Tunisian clinical isolate of Proteus mirabilis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 169:235-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Winokur, P. L., A. Brueggemann, D. L. DeSalvo, L. Hoffmann, M. D. Apley, E. K. Uhlenhopp, M. A. Pfaller, and G. V. Doern. 2000. Animal and human multidrug-resistant, cephalosporin-resistant Salmonella isolates expressing a plasmid-mediated CMY-2 AmpC beta-lactamase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2777-2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]