Abstract

Since 1996, the National Salmonella Reference Laboratory of Germany has received an increasing number of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B isolates. Nearly all of these belonged to the dextrorotatory tartrate-positive variant (S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+), formerly called S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Java. A total of 55 selected contemporary and older S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ isolates were analyzed by plasmid profiling, antimicrobial resistance testing, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, IS200 profiling, and PCR-based detection of integrons. The results showed a high genetic heterogeneity among 10 old strains obtained from 1960 to 1993. In the following years, however, new distinct multiresistant S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ clones emerged, and one clonal lineage successfully displaced the older ones. Since 1994, 88% of the isolates investigated were multiple drug resistant. Today, a particular clone predominates in some German poultry production lines, poultry products, and various other sources. It was also detected in contemporary isolates from two neighboring countries as well.

Zoonotic Salmonella enterica serovars are among the most important agents of food-borne infections throughout the world. Poultry, pigs, and cattle rank as the major sources of Salmonella-contaminated food products that cause human salmonellosis. Only a few Salmonella serovars predominate in an animal population or a country at a certain time. Currently there are global pandemics of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovars Enteritidis and Typhimurium DT104 (28, 39). However, from time to time less common serovars emerge and can cause outbreaks in humans or animals (1, 11, 37; World Health Organization Global Salmonella Survey list server message 2000-18, 10 May 2000).

One of the rare serovars is S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B, which can be differentiated by the use of dextrorotatory tartrate. The classical S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B is d-tartrate negative (dT−) (26) and a virulent human pathogen. The d-tartrate-positive (dT+) variant was formerly called S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Java (17). It is generally considered less virulent for humans, but some authors claim that it should not be underestimated as a possible cause of outbreaks of salmonellosis (3; World Health Organization Global Salmonella Survey list server [www.who.ch/salmsurv] message 2000-18, 10 May 2000). In recent years, the National Salmonella Reference Laboratory of Germany (NRL) has received an increasing number of S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ isolates originating from poultry and poultry products (9).

The aim of this study was to obtain information about the emergence and spread of dT+ variants of S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B isolates in Germany by determining their phenotypic and genotypic properties. A collection of contemporary and older S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ isolates of different origins and sources were characterized by several classical and DNA-based typing methods. The results of this study demonstrate the emergence of distinct S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ clones during the 1990s. One of them displaced the older clones successfully and is frequently encountered in German poultry, poultry products, and various other sources.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and selection of isolates.

The NRL receives about 5,000 Salmonella isolates annually from all Bundeslaender (federal states) of Germany for serotyping. They originate from routine surveys of different investigation centers involved in public health. In general the isolates are identified only as Salmonella and sent to the NRL for confirmation and detailed serotyping, as well as phage, resistance, and molecular typing. The NRL is quality controlled by the European Community Reference Laboratory and the World Health Organization Global Salmonella Survey program.

Detailed sources and properties of the d-tartrate-positive strains of S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B as well as the control strains used in this study are listed in Table 1 .

TABLE 1.

Sources and properties of S. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ and comparison strains

| Group and strain | Yr of isolation | Origina | Source | Antibiotic resistanceb | Integron size (bp) | Plasmid size (MDa) | PFGE profile

|

IS200 profile | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XbaI | SpeI | BlnI | |||||||||

| Group 1 | |||||||||||

| 970 | 1960 | NRL | Unknown | Sensitive | X1 | S1 | B1 | ISP1 | |||

| 1285 | 1961 | NRL | Unknown | Sensitive | X1 | S1 | B1 | ISP1 | |||

| 83 | 1984 | Unknown | Crustacean | Sensitive | X2 | S2 | B2 | ISP2 | |||

| 1061 | 1986 | Lower Saxony | Cat | Sensitive | X3 | S3 | B3 | ISP3 | |||

| 163 | 1986 | Bavaria | Bird | Sensitive | X3 | S3 | B3 | ISP3 | |||

| 1198 | 1986 | Bavaria | Environment | Sensitive | X4 | S4 | B4 | ISP4 | |||

| 1538 | 1989 | Unknown | Food, chicken | Sensitive | 3.6, 1.3 | X4 | S4 | B4 | ISP5 | ||

| 5707 | 1991 | Unknown | Unknown | Sensitive | X5 | S5 | B5 | ISP6 | |||

| 521 | 1993 | Münster | Milk product | Sensitive | X4 | S4 | B4 | ISP7 | |||

| 290 | 1993 | Remscheid | Meat, chicken | Sensitive | 3.9 | X6 | S6 | B6 | ISP8 | ||

| Group 2 | |||||||||||

| 1477 | 1994 | Bad Wildungen | Meat, chicken | TMP, STR, SUL, SXT, TET, CHL, NAL | 1,800 | 128, 3.9, 2.4 | X7 | S7 | B7 | ISP8 | |

| 350 | 1994 | Reisdorf | Meat, chicken | TMP, STR, SUL, SXT, TET, CHL | 1,800 | 128, 3.9, 2.4 | X7 | S7 | B7 | ISP8 | |

| 2504 | 1994 | Ueckermünde | Meat, chicken | TMP, STR, SUL, SXT, TET, CHL, NAL | 1,800 | 128, 3.9, 2.4 | X7 | S7 | B7 | ISP8 | |

| 2496 | 1995 | Brodersdorf | Meat, chicken | TMP, STR, SUL, SXT, TET, CHL, KAN, NEO, NAL | 1,800 | 128, 3.9, 2.4 | X7 | S7 | B7 | ISP8 | |

| 1721 | 1999 | Grub | Unknown | TMP, STR, SUL, SXT, TET, KAN, NEO, NAL | 1,800 | 128, 3.9, 2.4 | X7 | S7 | B7 | ISP8 | |

| 2696 | 1999 | Grub | Chicken | KAN, NEO, NAL | 88, 3.9, 2.4 | X7 | S7 | B7 | ISP8 | ||

| Group 3 | |||||||||||

| 232 | 1995 | Moehrendorf | Food, chicken | TMP, STR, SUL, SXT, NAL | 4.0 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 2021 | 1996 | Spessart | Meat, chicken | TMP | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | |||

| 2354 | 1996 | Forchheim | Meat, chicken | TMP, STR | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | |||

| 199 | 1997 | Berlin | Organs, chicken | TMP, STR, SUL, SXT, NAL | 62, 4.0, 2.4 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 487 | 1997 | Schwerin | Meat, chicken | TMP, STR, AMP | 62 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 558 | 1997 | Cottbus | Egg, chicken | TMP, AMP | 62 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 913 | 1997 | Stuttgart | Sewage | TMP, STR, SUL, SXT, NAL | 36, 4.0 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 1895 | 1998 | Bad Langensalza | Food | TMP, STR, SUL, SXT, NAL | 4.0, 3.6 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 1967 | 1998 | Berlin | Raw sausage | TMP, STR | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | |||

| 189 | 1998 | Chemnitz | Intestine, cattle | TMP, SUL, SXT, AMP, NAL, ENR | 62, 4.0 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 2399 | 1998 | Grub | Chicken | TMP, TET, KAN, NEO | 68, 4.0, 2.4 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 502 | 1999 | Jena | Droppings, chicken | TMP, STR, SUL, SXT, AMP, NAL | 62, 4.0 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 58 | 1999 | Jena | Droppings, chicken | TMP, AMP, NAL | 62 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 140 | 1999 | Jena | Droppings, chicken | TMP, SUL, SXT, AMP, NAL | 62, 4.0 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 135 | 1999 | Jena | Droppings, chicken | TMP, STR, SUL, SXT, AMP, NAL | 62, 4.0 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 53 | 1999 | Jena | Droppings, chicken | TMP, SUL, SXT, AMP, NAL | 62, 4.0 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 2674 | 1999 | Giessen | Organs, chicken | TMP, SUL, SXT, AMP | 68 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 2675 | 1999 | Giessen | Liver, chicken | TMP, SUL, SXT, AMP | 68, 2.4 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 2668 | 1999 | Giessen | Liver, chicken | TMP, STR, SUL, SXT, AMP | 68, 2.4 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 1965 | 1999 | Giessen | Chicken | TMP, STR | 4.2, 3.6, 2.4, 1.4 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 4312 | 1999 | Giessen | Meat, chicken | TMP | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | |||

| 2687 | 1999 | Grub | Chicken | TMP, STR, AMP | 62 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 1534 | 1999 | Berlin | Broiler | TMP, SUL, SXT, TET, KAN, NEO, NAL | 88, 4.0 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 593 | 2000 | Berlin | Scalding water | TMP | 1.4 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 612 | 2000 | Berlin | Neck skin | TMP | 1.4 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 1086 | 2000 | Giessen | Meat, chicken | TMP, STR, SUL, SXT, AMP, NAL | 62, 4.0, 2.4 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 1080 | 2000 | Giessen | Meat, chicken | TMP, STR, SUL, SXT, AMP, NAL | 62, 4.0, 2.4 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 1087 | 2000 | Giessen | Meat, chicken | TMP, STR, SUL, SXT, AMP, NAL | 62, 4.0, 2.4 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 1084 | 2000 | Giessen | Meat, chicken | TMP, SUL, SXT, AMP, NAL | 62, 4.0 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 1067 | 2000 | Giessen | Meat, chicken | TMP, NAL | 3.6 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 1156 | 2000 | Giessen | Meat, chicken | TMP, SUL, SXT | 62 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 1096 | 2000 | Giessen | Meat, chicken | TMP, SUL, SXT, AMP | 68 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 1063 | 2000 | Giessen | Meat, chicken | TMP, NAL | 3.6 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 1079 | 2000 | Giessen | Meat, chicken | TMP, STR, SUL, SXT, NAL | 4.0, 2.4 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 1768 | 2000 | Giessen | Giblets | TMP, STR, SUL, SXT | 62 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 1173 | 2000 | Giessen | Meat, chicken | TMP, NAL | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | |||

| 2933 | 2000 | Giessen | Unknown | TMP, STR, SUL, SXT, TET, AMP, NAL | 1,600 | 112, 62, 2.4 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | |

| 1386 | 2000 | Jena | Meat, chicken | TMP, SUL, SXT, AMP, NAL | 68 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| 1250 | 2000 | Sigmaringen | Salmon | TMP | 62, 3.8 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| Comparison strains

|

|||||||||||

| Brü2-1175 | 1997 | Belgium | Unknown | TMP, SUL, SXTCH, CHL | 70, 36, 4.0 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| Bi52 | 2000 | The Netherlands | Unknown | TMP, STR, SUL, SXT, TET, AMP | 1,600 | 90 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | |

| Bi3742 | 2000 | The Netherlands | Unknown | TMP, STR, AMP | 62, 4.7, 3.1 | X8 | S8 | B8 | ISP9 | ||

| W-S6497 | 1999 | England | Environment | Sensitive | X9 | S9 | B9 | ISP10 | |||

| W-S42000 | 2000 | England | Chicken | Sensitive | X9 | S9 | B9 | ISP10 | |||

| 2650 | 2000 | Berlin | Snake | Sensitive | 112, 92, 7, 5 | X10 | S10 | B10 | ISP11 | ||

| NCTC 5706c | 1937 | England | Unknown | Sensitive | X11 | S11 | B11 | ISP12 | |||

| 1328d | 2000 | Weiβentels | Unknown | AMP, CHL, STR, SUL, TET | 1,000/1,200 | 60 | X12 | S12 | B12 | ISP13 | |

All locations are in Germany unless indicated otherwise.

The antimicrobial agents used were amikacin (AMK, 30 μg), ampicillin (AMP, 10 μg), chloramphenicol (CHL, 30 μg), cefuroxime (CXM, 30 μg), colistin sulfate (COL, 10 μg), enrofloxacin (ENR, 5 μg), gentamicin (GEN, 10 μg), kanamycin (KAN, 30 μg), nalidixic acid (NAL, 30 μg), neomycin (NEO, 10 μg), polymyxin B (PB, 300 IU), streptomycin (STR, 25 μg), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT, 25 μg), sulfonamides (SUL, 300 μg), tetracycline (TET, 30 μg), and trimethoprim (TMP, 2.5 μg).

Reference strain.

Serovar Typhimurium phage type DT104.

All isolates from the years 1960 to 1995 and the comparative strains were selected on the basis of their availability. Old strains originated from stab cultures of the NRL strain collection.

Contemporary isolates were selected from routine submissions in order to represent all different resistance phenotypes, different geographic locations, and possible sources. Therefore, not only poultry but also, if available, bovine, environmental, and other sources were included.

In order to avoid the characterization of duplicates, strains from the same geographic location which were isolated at the same time by the same laboratory and which exhibited the same serovar and resistance profiles were excluded from the study.

Serotyping was performed according to the Kauffmann-White scheme, and strains were named serovar Paratyphi B when they exhibited the antigen formula 1,4,[5],12:b:1,2 (26). Identification of the strains as d-tartrate positive or negative was done as described by Dorn et al. (9).

Antimicrobial susceptibility test.

All of the serovar Paratyphi B strains were tested for their susceptibility to 16 antimicrobial agents by agar diffusion test in accordance with the guidelines of the German Institute for Standards (8) with antibiotic disks (Oxoid Ltd., London, England). The antimicrobial agents used were amikacin (30 μg), ampicillin (10 μg), chloramphenicol (30 μg), cefuroxime (30 μg), colistin sulfate (10 μg), enrofloxacin (5 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), kanamycin (30 μg), nalidixic acid (30 μg), neomycin (10 μg), polymyxin B (300 IU), streptomycin (25 μg), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (25 μg), sulfonamides (300 μg), tetracycline (30 μg), and trimethoprim (2.5 μg).

Conjugative transfer of resistance markers.

Two S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ strains each from group 2 (strains 2504 and 2496) and group 3 (1086 and 2933), harboring plasmids and revealing multiple antimicrobial resistance determinants, were selected for mating experiments. Escherichia coli strain J53, resistant to rifampin, nalidixic acid, and streptomycin, was used as the recipient strain. Liquid and solid mating experiments for suitable resistance markers (ampicillin and/or chloramphenicol, kanamycin, tetracycline, or trimethoprim) were performed at 37 and 22°C as described previously (15). Subsequently, the plasmid profiles and antibiotic resistance patterns of donor and transconjugant strains were compared.

Nucleic acid techniques. (i) Plasmid profile typing.

Plasmid DNA was extracted by the alkaline denaturation method of Kado and Liu (16) with minor modifications. Plasmids were electrophoretically separated in 0.7% horizontal agarose gels at 100 V for 3.5 h in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer. The plasmids were stained with an aqueous solution of ethidium bromide (10 μg/ml; Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) and photographed under UV illumination. The E. coli reference plasmids R27 (112 MDa), R1 (62 MDa), RP4 (36 MDa), and ColE1 (4.2 MDa) and the supercoiled DNA ladder (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Karlsruhe, Germany) served as size standards for the determination of plasmid sizes.

(ii) PCR amplification and amplicon purification.

Salmonella plasmid virulence region (spvC) tests for all serovar Paratyphi B dT+ strains were performed by PCR with the primers and cycling conditions described previously (7, 13). The assays were performed in 50-μl reaction volumes containing an amplification buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.4], 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2), 200 μM each of the four deoxynucleoside triphosphates (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), 1 μM each primer (TIB MOLBIOL, Berlin, Germany), 1 U of Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen), and 100 ng of template DNA, in a Perkin-Elmer Gene Amp system (model 2400). Amplicons were analyzed by electrophoresis on horizontal 1.5% agarose gels. A 100-bp ladder and the DNA molecular weight marker X (both from Roche Diagnostics) were used as molecular size markers. Control strains were the spvC-positive S. enterica serovars Typhimurium strain 184 and Choleraesuis strain 807 from the NRL strain collection.

Class 1 integron tests of strains and transconjugants were performed by PCR with the primers 5′CS and 3′CS (20). PCR amplification was carried out as described above with the cycling conditions cited previously (14).

For IS200 profiling, a 557-bp internal DNA probe was generated by PCR amplification as described previously (23) with the primers IS200-L2 and -R2 (5, 6). The amplification reactions were modified and contained 0.1 μM each primer (TIB MOLBIOL), 1 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml, approximately 50 ng of genomic DNA, and 2.5 U of Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen). The PCR product was purified with the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

(iii) Macrorestriction analysis.

Genomic DNA for pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) experiments was prepared in low-melting-point agarose gel plugs as previously described (23). Slices of the DNA-containing agarose plugs were incubated in a final volume of 100 μl overnight at 37°C with 10 U of XbaI, SpeI, or BlnI (all from Roche Diagnostics). The plugs were melted at 65°C, and DNA fragments were subjected to PFGE in 1% (wt/vol) agarose (Seakem GTG agarose; FMC BioProducts) in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer on a CHEF-DR III system (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany) at 10°C. Pulse times were ramped from 5 to 50 s during a 24-h run (XbaI), 4 to 40 s during a 24-h run (SpeI), or 20 to 80 s during a 25-h run (BlnI) at 6 V/cm. A lambda ladder (New England Biolabs, Frankfurt, Germany) was used as molecular size markers. DNA fragment patterns were assessed visually, and PFGE profiles were assigned according to published guidelines (34, 35). A minimum of three band differences in the electrophoretic pattern defined a distinct PFGE profile. Only fragments larger than 40 kb were evaluated.

(iv) IS200 profiling.

Genomic DNA was isolated from 1.5 ml of an overnight broth culture either by the method of Wilson (38) or with the Qiagen blood and cell culture DNA mini kit (Qiagen). DNA was digested at 37°C for 4 h with the restriction enzyme PstI (Roche Diagnostics), which lacks restriction sites within the IS200 sequence (12, 19). The resulting DNA fragments were subsequently separated by electrophoresis through 0.7% agarose gels with Tris-borate-EDTA buffer as the running buffer at 45 V for 18 h. A 1-kb ladder (Invitrogen) and the digoxigenin-labeled DNA molecular weight marker II (Roche Diagnostics) served as molecular mass markers. The gels were stained with ethidium bromide and photographed under UV illumination. The DNA fragments were transferred from agarose gels to positively charged nylon membranes (Roche Diagnostics) in 10× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) with a vacuum blotter (model 785; Bio-Rad) and fixed to the membrane by cross-linking.

Labeling of the purified 557-bp PCR-product used as the probe (described above), prehybridization, hybridization under stringent conditions, and colorimetric signal detection were carried out with the digoxigenin High Prime labeling and detection starter kit I (Roche Diagnostics) according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

RESULTS

Incidence of S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+.

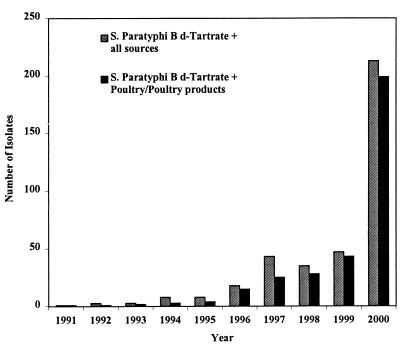

Figure 1 shows the number of S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ isolates received at the NRL each year from 1991 to 2000. In the years before 1996, this serovar was only sporadically encountered (less than 10 isolates per year). Since then, a steady increase has been observed, encompassing 213 (5.4%) of the 3,915 isolates received in 2000. Ninety-three percent of the S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ isolates originated from poultry and poultry products, and 99% were multiresistant.

FIG. 1.

Incidence of S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ strains received at the NRL from 1991 to 2000.

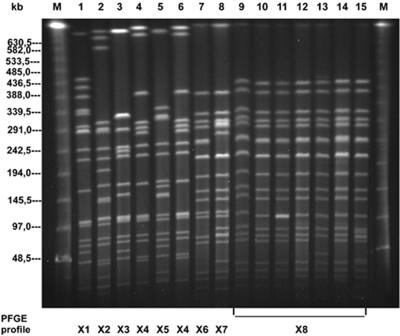

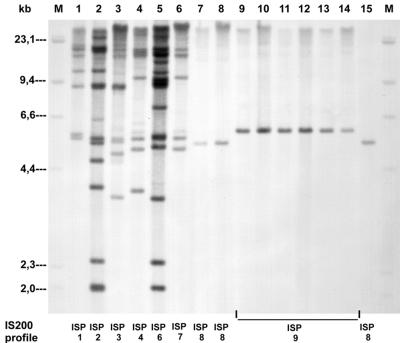

In order to investigate the clonal descent of these isolates, 55 selected German S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ strains and 8 epidemiologically unrelated comparison strains were included in this study. The contemporary strains represented all different resistance phenotypes, different geographic locations, and possible sources of the isolates received. The phenotypic properties and molecular typing results are summarized in Table 1. Representative results of the molecular typing studies are shown in Fig. 2 and 3.

FIG. 2.

PFGE profiles of representative S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ strains after digestion with XbaI. Lanes M contain molecular size markers (lambda ladder PFG marker; New England Biolabs). Lanes 1 to 15 contain DNA samples from the following strains and groups: group 1: 1, 1285; 2, 83; 3, 163; 4, 1198; 5, 5707; 6, 521; and 7, 290; group 2: 8, 2504; group 3: 9, 232; 10, 1086; 11, 2399; 12, 189; 13, 135; 14, 2675; and 15, 2933.

FIG. 3.

IS200 profiles of representative S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ strains. Lanes M contain molecular size markers (digoxigenin-labeled DNA molecular weight marker II; Roche). Lanes 1 to 15 contain DNA samples from the following strains and groups: group 1: 1, 1285; 2, 83; 3, 163; 4, 1198; 5, 5707; 6, 521; and 7, 290; group 2: 8, 2504; and 15, 2696; group 3: 9, 232; 10, 1086; 11, 2399; 12, 189; 13, 135; and 14, 2675.

Altogether, these data show that the strains could be divided into three groups differing in major phenotypic and genotypic properties.

Properties of old S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ strains (group 1).

Group 1 consisted of 10 old strains which originated mainly from sources other than poultry. All strains were sensitive to the antimicrobial agents tested. Only one strain harbored two small plasmids (3.6 and 1.3 MDa), one strain carried a 3.9-MDa plasmid, and the other strains possessed no plasmid at all.

Macrorestriction analysis (Table 1) performed with the three restriction endonucleases XbaI, SpeI, and BlnI revealed heterogeneity, with six distinct PFGE profiles (X1 to X6, S1 to S6, and B1 to B6). XbaI patterns X1 to X6 were characterized by 16 to 20 fragments ranging in size from 20 to 700 kb, SpeI patterns S1 to S6 were characterized by 16 to 21 fragments ranging in size from 20 to 485 kb, and BlnI patterns B1 to B6 were characterized by 7 to 10 fragments ranging in size from 20 to 750 kb. Figure 2 (lanes 1 to 7) shows the PFGE profiles of seven representative old S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ strains after digestion with XbaI as an example (BlnI and SpeI data not shown).

IS200 (JSP) profiles revealed 1 to 14 IS200 copies per strain, with corresponding fragment sizes of 1.9 to >21.3 kb. Eight distinct IS200 profiles, ISP1 to ISP8 (Table 1), were observed, confirming the above-mentioned diversity among these older strains. Figure 3 (lanes 1 to 7) shows the IS200 profiles of the same seven representative old S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ strains as an example.

Properties of mid-1990s S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ strains (group 2).

Group 2 was represented by four strains isolated from chicken meat in different German regions in the mid-1990s and two strains from 1999. These strains differ from the first group and represent a new clone. All these strains except 2696 exhibited a core spectrum of antibiotic resistance determinants for trimethoprim, streptomycin, sulfonamides, and tetracycline. Additional resistances to kanamycin/neomycin and nalidixic acid were found in some isolates. Plasmid profiling revealed that all of the strains except 2696 were characterized by a plasmid of 128 MDa and two plasmids of 3.9 and 2.4 MDa. Conjugation experiments showed that the resistance to chloramphenicol, tetracycline, and trimethoprim (strain 2504) and chloramphenicol, kanamycin, tetracycline, and trimethoprim (strain 2496) was transferable at 22°C in one linkage group on the 128-MDa plasmid (data not shown). Strain 2696 carried only an 88-Mda plasmid and had lost trimethoprim, streptomycin, sulfonamide, and tetracycline resistance.

The macrorestriction analysis revealed PFGE patterns differing by only one to two fragments in the high-molecular-weight range. All these strains were assigned to PFGE profile X7/S7/B7 (Table 1). Figure 2 illustrates the PFGE pattern of a representative group 2 Paratyphi B dT+ strain in lane 8.

The IS200 profiles (ISP8) of these isolates were very homogeneous as well (Table 1), showing only one IS200 band at 5.4 kb (Fig. 3, lane 8). This profile has been detected in sensitive strain 290 of group 1 from 1993 as well.

Properties of contemporary German S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ strains (group 3).

Group 3 included 39 isolates from the second half of the 1990s and from 2000. Thirty-three strains originated from poultry and poultry products (Table 1). The remaining six isolates were isolated from cattle, fish, sewage, or unknown sources. All 39 isolates were resistant to trimethoprim. Nearly 50% of the strains were resistant to four or more antimicrobial substances, with predominant resistance to sulfonamides (59%), nalidixic acid (54%), ampicillin (49%), and streptomycin (46%) in addition to trimethoprim. Ciprofloxacin resistance (MIC, 0.25 to 2 μg/ml) could be detected in 40% of the year 2000 isolates (B. Malorny, unpublished data).

Plasmid analysis revealed the presence of 16 different plasmid profiles, consisting of one to four plasmids of between 1.4 and 112 MDa, with the most common plasmids being 62, 4.0, and 2.4 MDa in size. Five isolates were plasmid-free (Table 1). None of the isolates in this study carried spvC-related sequences, as determined by PCR.

Strain 1086 and strain 2933 (Table 1) were selected as representatives of group 3 for conjugation experiments. Both strains transferred the ampicillin resistance on the 62-MDa plasmid at 37°C in liquid matings. Strain 1086 cotransferred sulfonamide resistance on the 62-MDa plasmid as well. Strain 2933 transferred resistance to sulfonamides, tetracycline, and trimethoprim in one linkage group on the 112-MDa plasmid.

In PFGE analysis, each of the restriction enzymes yielded in all cases a typical, uniform PFGE profile (X8, S8, B8) (Table 1). As an example, Fig. 2 (lanes 9 to 15) shows the macrorestriction profile X8 of seven representative contemporary S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ strains from group 3.

The clonal similarity of the group 3 strains was confirmed by the fact that all strains showed an identical IS200 profile (ISP9), with only one IS200 band of 5.8 kb (Fig. 3, lanes 9 to 14).

Properties of comparison strains.

As shown in Table 1, contemporary isolates from Belgium (Brü2-1175) and The Netherlands (Bi52 and Bi3742) showed properties similar to those of the contemporary German isolates. With the PFGE profile X8, S8, B8 and IS200 profile ISP9, these isolates could also be assigned to the third group of German strains.

Two contemporary isolates from England, W-S6497 and W-S42000, in contrast, were revealed in the macrorestriction analysis and in IS200 profiling patterns (X9, S9, B9; ISP10) to be highly different from the German ones. In addition, both isolates were sensitive to all of the antimicrobial agents tested and did not harbor any plasmids (Table 1).

Strain 2650, a strain originating from a snake, was sensitive to all of the antimicrobial agents tested but possessed four plasmids of 112, 92, 7, and 5 MDa. The patterns (X10, S10, B10; ISP11) obtained by both molecular typing methods were unique and not comparable to any of the other patterns (Table 1).

NCTC 5706, a 1937 monophasic reference strain from the National Collection of Type Cultures in London, England, was sensitive, possessed no plasmid, and showed a unique pattern (X11, S11, B11; ISP12) by PFGE and IS200 profiling as well (Table 1).

Strain 1328, a contemporary serovar Typhimurium strain of the epidemiologically important phage type DT104, was characterized by pentaresistance (ampicillin, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, sulfonamides, and tetracycline), a plasmid of 60 MDa, PFGE profile X12, and IS200 profile ISP13, both typical of serovar Typhimurium DT104 strains. Consequently, the profile of this strain differed from the profiles of the S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ strains (Table 1).

Detection of class 1 integrons.

All strains included in this study and all transconjugants were screened by PCR for the presence of class 1 integrons with specific primers targeting the conserved 5′ and 3′ segments of the integron. No integron was detectable in the old, antibiotic-sensitive strains of group 1. In contrast, in five of the six resistant strains of group 2, a class 1 integron generating a PCR product of about 1,800 bp was found. This integron resided on the 128-MDa conjugative plasmid, because all transconjugants gave rise to the same PCR amplicon as the donor. In addition, strain 2696, which lacked trimethoprim, streptomycin, sulfonamide, and tetracycline resistance, also did not carry the integron.

The majority (38 of 39) of the group 3 strains did not carry any class 1 integron. Only strain 2933 carried an integron with an amplicon of about 1,600 bp. It was located on the 112-MDa plasmid, as shown by analysis of the transconjugants.

The comparison strain Bi52 from The Netherlands also harbored an integron with an amplicon of about 1,600 bp. Its properties resembled those of the group 3 strains.

DISCUSSION

Only a few studies deal with typing of strains of serovar Paratyphi B because so far this serovar has not played a significant epidemiological role. In 1988, Barker et al. (2) studied variation in a worldwide collection of 338 isolates of S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B. They defined 13 biotypes, phage types, and ribotypes. On the basis of these properties, strains were assigned to three groups. Selander et al. (30, 31) applied multilocus enzyme electrophoresis to distinguish 14 electrophoretic types (ETs) within S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B. The authors observed considerable genotypic diversity among ETs and concluded that most dT− strains comprised a globally distributed clone, Pb1, with highly polymorphic phenotypes, whereas dT+ strains represented seven clonal lineages. Ezquerra et al. (10) in their study found 13 unique IS200 profiles among representative S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B strains and were able to distinguish distinct genotypes of S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT− and dT+. One of the S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT− profiles, Spj-IP1.0, represented a globally distributed clone. Greater diversity was detected within the IS200 profiles of S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ isolates. The authors hypothesized that since S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ has many animal and human hosts, a variety of selection pressures exist for the evolution of genetic diversity.

The increasing incidence of S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ strains in Germany and neighboring countries, especially in poultry and poultry products, indicates the growing importance of this pathogen. The study presented was initiated by the need to obtain more information about the phenotypic and molecular properties of this Salmonella serovar and the emergence and spread of clonal lines in Germany. In addition to classical typing methods, molecular typing methods such as plasmid profiling, macrorestriction analysis, IS200 profiling, and PCR detection of integrons were used. These techniques have proven to be useful procedures in subtyping other Salmonella serovars (1, 14, 18, 22-25, 32, 33, 36).

The data presented here confirmed the genetic diversity of the S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ strains described by Selander et al. (30, 31) in 1990 and by Ezquerra et al. (10) in 1993. However, genetic diversity was detected only in a group of older German S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ strains originating from the beginning of the 1960s to the beginning of the 1990s and in foreign comparison strains. These drug-sensitive and generally plasmid-free strains showed several diverse patterns by PFGE and IS200 profiling, suggesting the existence of coexisting clones. In subsequent years, the situation changed. The data presented show that in the middle of the 1990s, new clones of S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ originating from poultry and poultry products emerged in Germany and spread. They were multiresistant and could have been selected by the increasing use of antimicrobial agents in poultry production due to attempts to manage the serovar Enteritidis crisis. One clone was resistant to chloramphenicol, sulfonamide, tetracycline, and trimethoprim, and some isolates were resistant to kanamycin, neomycin, and/or nalidixic acid as well. The multiresistance was found to be located on a transferable 128-MDa plasmid and to be associated with a class 1 integron. Strains of this clone exhibited a unique PFGE profile (X7) and a unique IS200 profile (ISP8). This clone did not disappear completely, because two isolates could be detected at the end of the 1990s as well.

In 1995, a new clonal line emerged and spread successfully. Today it represents the majority of contemporary strains and has replaced almost all other clones. This clonal line is found predominantly in Germany in poultry and poultry products and has been isolated from other sources such as cattle, fish, and sewage as well. Strains of this clonal line are characterized by a variety of plasmid profiles as well as resistance patterns composed of resistance to trimethoprim alone or, in 87% of the cases, in combination with resistance to streptomycin, sulfonamides, nalidixic acid, and/or ampicillin.

On the chromosomal level, strains belonging to the dominant clonal line are highly uniform with respect to molecular typing by macrorestriction analysis (PFGE profile X8) and IS200 profiling (ISP9).

The data from the study presented demonstrate the emergence of multidrug resistance among S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ strains in Germany during the last decade. Several mechanisms involving mobile genetic elements, such as plasmids and transposons, have been shown to contribute to the spread of resistance (21). Integrons, able to incorporate antibiotic resistance gene cassettes by site-specific recombination, have been identified on these mobile elements (27). Class 1 integrons, the most prevalent integron class in gram-negative bacteria, are also widespread among many Salmonella serovars (4, 14, 29). Therefore, it was not unexpected that class 1 integrons could also be found in multiresistant S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ strains. Although the contemporary S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ clone is multiresistant, integrons are not important for this phenotype. Characterization of the major genes conferring antimicrobial resistance in all S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B dT+ strains tested is presently being carried out.

Acknowledgments

The skilled technical assistance of K. Pries, C. Bunge-Croissant, G. Berendonk, and B. Hoog is highly appreciated. We thank W. Wannett (RIVM, NL) and H. Imberechts (CODA, Belgium) for kindly providing strains Bi52, Bi3742, and Brü2-1175.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baquar, N., A. Burnens, and J. Stanley. 1994. Comparative evaluation of molecular typing of strains from a national epidemic due to Salmonella brandenburg by rRNA gene and IS200 probes and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:1876-1880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker, R. M., G. M. Kearney, P. Nicholson, A. L. Blair, R. C. Porter, and P. B. Crichton. 1988. Types of Salmonella paratyphi B and their phylogenetic significance. J. Med. Microbiol. 26:285-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breitenfeld, V., and D. Aleraj. 1967. Klinische und bakteriologische Eigenschaften der durch Salmonella java verursachten Salmonellose. Zentbl. Bakteriol. Abt. 1 204:89-99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown, A. W., S. C. Rankin, and D. J. Platt. 2000. Detection and characterisation of integrons in Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 191:145-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burnens, A. P., J. Stanley, R. Sack, P. Hunziker, I. Brodard, and J. Nicolet. 1997. The flagellin N-methylase gene fliB and an adjacent serovar-specific IS200 element in Salmonella typhimurium. Microbiology 143:1539-1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burnens, A. P., J. Stanley, I. Sechter, and J. Nicolet. 1996. Evolutionary origin of a monophasic Salmonella serovar, 9,12:l,v:_, revealed by IS200 profiles and restriction fragment polymorphisms of the fliB gene. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:1641-1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiu, C. H., and J. T. Ou. 1996. Rapid identification of Salmonella serovars in feces by specific detection of virulence genes, invA and spvC, by an enrichment broth culture-multiplex PCR combination assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:2619-2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deutsches Institut für Normung. 1989. Methods for the determination of susceptibility of pathogens (except mycobacteria) to antimicrobial agents; agar diffusion test DIN 58940, part 3. Deutsches Institut für Normung e.V., Berlin, Germany.

- 9.Dorn, C., A. Schroeter, A. Miko, and R. Helmuth. 2001. Gehäufte Einsendungen von Salmonella Paratyphi B-Isolaten aus Schlachtgeflügel an das Nationale Referenzlabor für Salmonellen. Berlin München Tierärztl. Wochenschr. 114:179-183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ezquerra, E., A. Burnens, C. Jones, and J. Stanley. 1993. Genotypic typing and phylogenetic analysis of Salmonella paratyphi B and S. java with IS200. J. Gen. Microbiol. 139:2409-2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fantasia, M., B. Paglietti, E. Filetici, M. P. Anastasio, and S. Rubino. 1997. Conventional and molecular approaches to isolates of Salmonella hadar from sporadic and epidemic cases. J. Appl. Microbiol. 82:494-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibert, I., K. Carroll, D. R. Hillyard, J. Barbé, and J. Casadesus. 1991. IS200 is not a member of the IS600 family of insertion sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guerra, B., I. Laconcha, S. M. Soto, M. A. González-Hevia, and M. C. Mendoza. 2000. Molecular characterisation of emergent multiresistant Salmonella enterica serotype [4,5,12:i:−] organisms causing human salmonellosis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 190:341-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guerra, B., S. Soto, S. Cal, and M. C. Mendoza. 2000. Antimicrobial resistance and spread of class 1 integrons among Salmonella serotypes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2166-2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helmuth, R., R. Stephan, E. Bulling, W. J. Van Leeuwen, J. D. A. Van Embden, P. A. M. Guinée, D. Portnoy, and S. Falkow. 1981. R-factor cointegrate formation in Salmonella typhimurium bacteriophage type 201 strains. J. Bacteriol. 146:444-452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kado, C. I., and S.-T. Liu. 1981. Rapid procedure for detection and isolation of large and small plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 145:1365-1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kauffmann, F. 1955. Zur Differentialdiagnose und Pathogenität von Salmonella java und Salmonella paratyphi B. Zeitschr. Hyg. 141:546-550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laconcha, I., D. L. Baggesen, A. Rementeria, and J. Garaizar. 2000. Genotypic characterisation by PFGE of Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis phage types 1, 4, 6, and 8 isolated from animal and human sources in three European countries. Vet. Microbiol. 75:155-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lam, S., and J. R. Roth. 1986. Structural and functional studies of insertion element IS200. J. Mol. Biol. 187:157-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lévesque, C., L. Piché, C. Larose, and P. H. Roy. 1995. PCR mapping of integrons reveals several novel combinations of resistance genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:185-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liebert, C. A., R. M. Hall, and A. O. Summers. 1999. Transposon Tn21, flagship of the floating genome. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63:507-522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liebisch, B., and S. Schwarz. 1996. Evaluation and comparison of molecular techniques for epidemiological typing of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Dublin. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:641-646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malorny, B., A. Schroeter, C. Bunge, B. Hoog, A. Steinbeck, and R. Helmuth. 2001. Evaluation of molecular typing methods for Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium DT104 isolated in Germany from healthy pigs. Vet. Res. 32:119-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olsen, J. E., M. N. Skov, O. Angen, E. J. Threlfall, and M. Bisgaard. 1997. Genomic relationships between selected phage types of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotype typhimurium defined by ribotyping, IS200 typing and PFGE. Microbiology 143:1471-1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olsen, J. E., M. N. Skov, E. J. Threlfall, and D. J. Brown. 1994. Clonal lines of Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis documented by IS200-, ribo-, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and RFLP typing. J. Med. Microbiol. 40:15-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Popoff, M. Y., and L. L. Minor. 1997. Antigenic formulas of the Salmonella serovars. W.H.O. Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Salmonella, Institute Pasteur, Paris, France.

- 27.Recchia, G. D., and R. M. Hall. 1995. Gene cassettes: a new class of mobile element. Microbiology. 141:3015-3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saeed, A. M., R. K. Gast, M. E. Potter, and P. G. Wall. 1999. Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis in humans and animals — epidemiology, pathogenesis, and control. Iowa State University Press, Ames, Iowa.

- 29.Sandvang, D., F. M. Aarestrup, and L. B. Jensen. 1998. Characterisation of integrons and antibiotic resistance genes in Danish multiresistant Salmonella enterica Typhimurium DT104. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 160:37-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Selander, R. K., P. Beltran, N. H. Smith, R. M. Barker, P. B. Crichton, D. C. Old, J. M. Musser, and T. S. Whittam. 1990. Genetic population structure, clonal phylogeny, and pathogenicity of Salmonella paratyphi B. Infect. Immun. 58:1891-1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Selander, R. K., P. Beltran, N. H. Smith, R. Helmuth, F. A. Rubin, D. J. Kopecko, K. Ferris, B. D. Tall, A. Cravioto, and J. M. Musser. 1990. Evolutionary genetic relationships of clones of Salmonella serovars that cause human typhoid and other enteric fevers. Infect. Immun. 58:2262-2275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stanley, J., N. Baquar, and A. Burnens. 1995. Molecular subtyping scheme for Salmonella panama. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1206-1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stanley, J., A. Burnens, N. Powell, N. Chowdry, and C. Jones. 1992. The insertion sequence IS200 fingerprints chromosomal genotypes and epidemiological relationships in Salmonella heidelberg. J. Gen. Microbiol. 138:2329-2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Struelens, M. J., A. Bauernfeind, A. Van Belkum, et al. 1996. Consensus guidelines for appropriate use and evaluation of microbial epidemiologic typing systems. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2:2-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Threlfall, E. J., M. L. Hall, L. R. Ward, and B. Rowe. 1992. Plasmid profiles demonstrate that an upsurge in Salmonella berta in humans in England and Wales is associated with imported poultry meat. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 8:27-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Threlfall, E. J., M. D. Hampton, L. R. Ward, I. R. Richardson, S. Lanser, and T. Greener. 1999. Pulsed field gel electrophoresis identifies an outbreak of Salmonella enterica serotype Montevideo infection associated with a supermarket hot food outlet. Commun. Dis. Public Health 2:207-209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilson, K. 1994. Preparation of genomic DNA from bacteria, p. 2.4.1-2.4.5. In F. M. Ausubel, R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.), Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Boston, Mass. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Wray, C., and A. Wray. 2000. Salmonella in domestic animals. CABI Publishing, Wallingford, United Kingdom.