Abstract

During 1999, we used partial 16S rRNA gene sequencing for the prospective identification of atypical nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli isolated from patients attending our cystic fibrosis center. Of 1,093 isolates of nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli recovered from 148 patients, 46 (4.2%) gave problematic results with conventional phenotypic tests. These 46 isolates were genotypically identified as Pseudomonas aeruginosa (19 isolates, 12 patients), Achromobacter xylosoxidans (10 isolates, 8 patients), Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (9 isolates, 9 patients), Burkholderia cepacia genomovar I/III (3 isolates, 3 patients), Burkholderia vietnamiensis (1 isolate), Burkholderia gladioli (1 isolate), and Ralstonia mannitolilytica (3 isolates, 2 patients), a recently recognized species.

Nonfermenting, gram-negative bacilli are the bacteria most frequently recovered from the sputum of patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) during the chronic stage (11). Most studies have shown Pseudomonas aeruginosa to be the species most frequently isolated (4, 21), followed by Burkholderia cepacia, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, and Achromobacter xylosoxidans. Other Burkholderia species such as Burkholderia gladioli are more rarely involved (5). These organisms differ in terms of pathogenic potential and transmissibility, and their identification to species level is therefore critical for the clinical management of CF patients. Conventional phenotypic methods are not suitable for CF strains, which often generate colonies of atypical appearance and lack key metabolic characteristics (9). In most cases, the antibiotic susceptibility pattern is not informative, with many of these isolates displaying multidrug resistance. Recent reports have emphasized the high frequency of misidentification problems, even in diagnostic laboratories with experience in working with organisms isolated from CF patients (3, 5, 12, 16-19).

Several genotypic methods have been developed for the identification of nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli in CF patients. Most are based on 16S rRNA gene polymorphism and involve PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis, single-strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP) analysis, or partial sequencing (1, 2, 5, 6, 10, 13, 18, 23). Other targets such as the recA gene have been proposed more recently (14, 15). Most of these genotypic methods were performed by research or reference laboratories and were based on the retrospective analysis of isolates sent by referring laboratories for problems of identification. These studies provided very little information about the prevalence of isolates unidentifiable in conventional tests at each CF center. Moreover, many of them focused on members of the genus Burkholderia, and other CF pathogens were only dealt with if misidentified as Burkholderia sp. (5, 7, 13, 14, 16, 18). The extent to which genotypic approaches have increased epidemiological knowledge concerning nonfermenting, gram-negative rods in CF centers is therefore unknown.

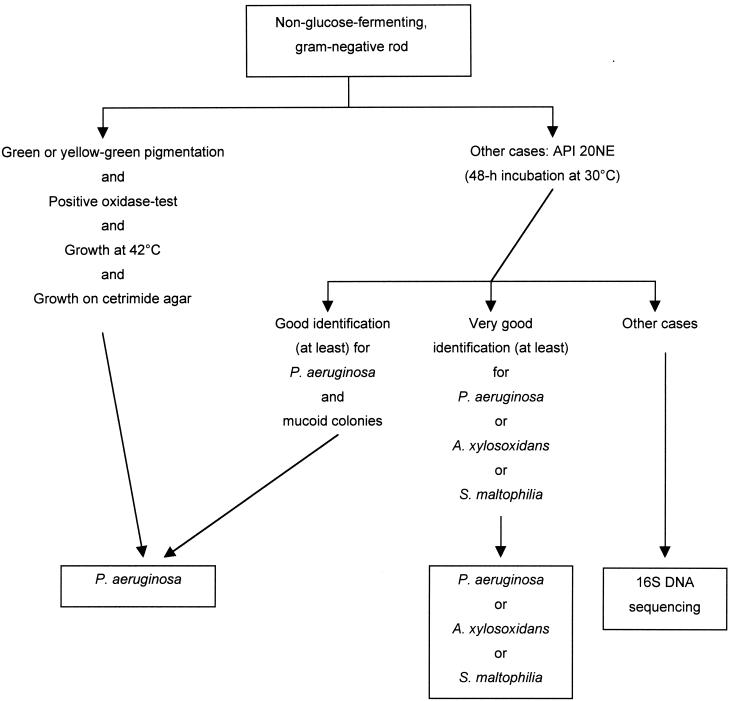

During 1999, we used partial 16S rRNA gene (16S DNA) sequencing for the prospective identification of atypical nonfermenting, gram-negative bacilli recovered from the sputum of CF patients attending the pediatric department of the Necker-Enfants Malades hospital. Sputum samples were plated on blood agar, chocolate-polyvitex agar, mannitol salt agar (BioMérieux, Marcy-l'Etoile, France), cetrimide agar, and B. cepacia-selective medium agar (AES, Combourg, France). Cultures were incubated for 48 h at 35°C and then for 6 days at 25°C. Antibiotic susceptibility was evaluated by a disk diffusion method (Bio-Rad, Marnes la Coquette, France) on Mueller-Hinton agar, supplemented with 5% horse blood as required. Nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli were identified according to a strategy (Fig. 1) based on previous results obtained at our laboratory with capillary electrophoresis-SSCP (10). Conventional tests (20) and the API 20NE system (BioMérieux) were used for phenotypic identification. The results of the API 20NE biochemical tests were read after 48 and 72 h of incubation at 30°C. Oxidase activity was checked with dimethyl-paraphenylenediamine disks (BioMérieux). The results of the API 20NE tests and of the oxidase reaction were further interpreted with the APILAB PLUS (version 3.3.3) software package.

FIG. 1.

Identification scheme used during the study.

Isolates for which identification with conventional tests was problematic (Fig. 1) were analyzed by partial 16S DNA sequencing. Bacterial strains were cultured overnight at 35°C on tryptic soy agar, and one or two colonies were suspended in 100 μl of distilled water. Bacterial cells were lysed by heating at 100°C for 10 min. The lysate was centrifuged for 2 min, and 5 μl of the supernatant was then directly used for PCR. The PCR mixture (final volume, 100 μl) contained a 0.1 μM concentration of each primer, 200 μM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Perkin Elmer, Foster City, Calif.) in 1× amplification buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2). We used the MM3 (5′-GCA GCA GTG GGG AAT TTT GG) and P13 (5′-AGG CCC GGG AAC GTA TTC AC) primers to amplify a 995-bp fragment (Escherichia coli 16S rRNA positions 371 to 1370; accession number JO695). PCR was performed in a Perkin-Elmer 9600 thermocycler (Norwalk, Conn.) with 40 cycles of 20 s at 94°C, 20 s at 55°C, 45 s at 72°C, and a final extension of 10 min at 72°C. The amplicons were then purified by filtration through a purification column (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden), and both strands were sequenced with an ABI Prism 310 sequencer (Perkin Elmer), using the BigDye Terminator cycle sequencing kit (Perkin Elmer). Sequences were edited with the Sequence Navigator program (Applied Biosystems) and aligned using ClustalW (version 1.8; Infobiogene). Sequences were first sent to the GenBank database for preliminary species or genus assignment. For further analysis, they were compared with 16S DNA sequences from appropriate reference strains, either determined in our laboratory or registered in the GenBank database (Table 1). Trees were constructed by a neighbor-joining method (neighbor program of the PHYLIP package [version 3.5c; J. Felsenstein, Department of Genetics, University of Washington, Seattle, 1993]).

TABLE 1.

Reference 16S sequences used in this study

| Species | Strain designation | Accession no. (GenBank) |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | ATCC 10145T | AF094713 |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | ATCC 13525T | AF094725 |

| Pseudomonas putida | ATCC 12633T | AF094736 |

| Pseudomonas stutzeri | ATCC 17588T | AF094748 |

| Pseudomonas alcaligenes | ATCC 14909T | AF094721 |

| Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes | LMG 1225T | Z76666 |

| Burkholderia cepacia | ATCC 25416T | AF097530 |

| Burkholderia cepacia genomovar III | LMG 12614 | AF311970 |

| Burkholderia multivorans | LMG 13010T | Y18703 |

| Burkholderia stabilis | LMG 14294T | AF148554 |

| Burkholderia vietnamiensis | TVV75T | U96928 |

| Burkholderia cocovenenans | LMG 11626T | U96934 |

| Burkholderia andropogonis | ATCC 23061 | X67037 |

| Burkholderia caryophilli | ATCC 25418 | AB021423 |

| Burkholderia gladioli | ATCC 10248T | X67038 |

| Burkholderia glumae | LMG 2196T | U96931 |

| Burkholderia plantarii | LMG 9035T | U96933 |

| Ralstonia pickettii | ATCC 27511T | AF467977 (this study) |

| Ralstonia solanacearum | ATCC 11696T | X67036 |

| Ralstonia mannitolilytica | LBV 407 | AJ270257 |

| Ralstonia mannitolilytica | LMG 6866T | AJ270258 |

| Ralstonia eutropha | JS705 | AF027407 |

| Ralstonia gilardii | LMG 5886T | AF076645 |

| Ralstonia paucula | LMG 3413 | AF085226 |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | LMG 958T | X95923 |

| Achromobacter xylosoxidans subsp denitrificans | ATCC 15173T | M22509 |

| Achromobacter xylosoxidans subsp. xylosoxidans | CIP 7132T | AF467978 (this study) |

| Alcaligenes faecalis | ATCC 8750T | M22508 |

| Alcaligenes piechaudii | ATCC 43552T | AB010841 |

During the study period, 1,257 sputum samples from 259 CF patients were subjected to cyto-bacteriological analysis. A total of 1,093 isolates of nonfermenting, gram-negative bacilli were recovered from 702 sputum samples (148 patients). Of these 1,093 isolates, 1,047 (95.8%) could be identified with conventional tests and/or the API 20NE system. They included 1,020 isolates of P. aeruginosa (140 patients), 17 isolates of A. xylosoxidans (11 patients), and 10 isolates of S. maltophilia (7 patients). The 46 remaining isolates (4.2% of isolates; 27 patients) gave problematic results in routine laboratory tests. Fifteen (33%) of these isolates were resistant to all antibiotics in routine testing, and 11 (24%) were resistant to all antibiotics except colistin.

The 46 problematic isolates in routine laboratory tests were studied by 16S DNA sequencing. Eighteen (12 patients) were identified as P. aeruginosa. The sequences obtained from these isolates were strictly identical to that of P. aeruginosa ATCC 10145T and differed from the most closely related Pseudomonas species, Pseudomonas alcaligenes and Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes, by 9 bp (ATCC 14909T) and 19 bp (LMG 1225T), respectively. The isolates were also clearly different from the members of the fluorescent pseudomonad group, Pseudomonas putida and Pseudomonas fluorescens (>35-bp difference). Ten isolates (8 patients) were identified as A. xylosoxidans subsp. xylosoxidans. The sequences obtained from these isolates were identical (3 isolates) or differed by only 1 bp (T-C 471, 7 isolates) from that of A. xylosoxidans subsp. xylosoxidans CIP 7132T. They differed by 2 to 3 bp from that of A. xylosoxidans subsp. denitrificans ATCC 15173T (T-C 471, A-G 1023, and G-C 1025, 7 isolates; A-G 1023 and G-C 1025, 3 isolates). The 16S DNA sequences of Achromobacter piechaudii (>5 bp) and Alcaligenes faecalis (>40 bp) were much less similar. Nine isolates (9 patients) were identified as S. maltophilia. Three were identical to, and six had 1 or 2 bp differences from, the S. maltophilia LMG 958T sequence (T-C 462, 2 isolates; A-G 646, 2 isolates; both substitutions, 2 isolates).

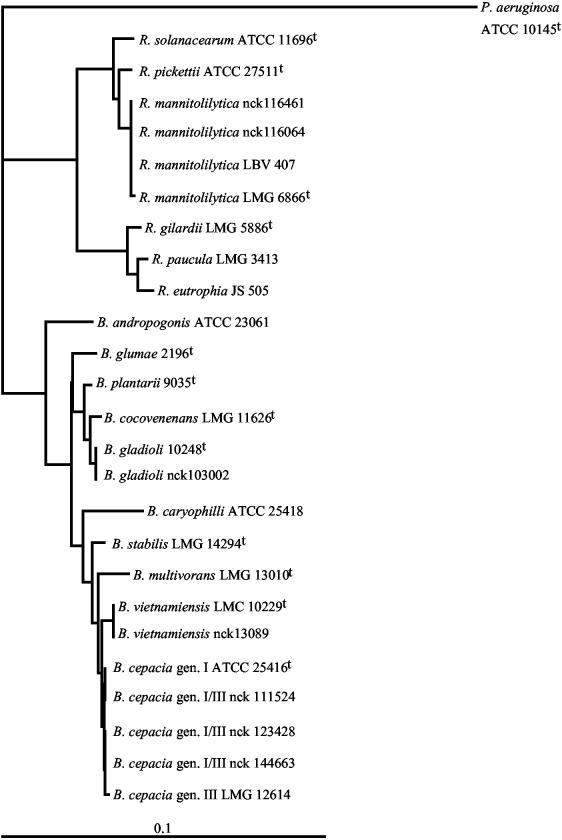

Five isolates (5 patients) belonged to the genus Burkholderia. Three isolates (3 patients) were identified as B. cepacia genomovar I/III. The sequences of these isolates differed by 1 or 2 bp from the B. cepacia ATCC 25416T sequence (A-G 927, 1 isolate; A-G 927 and C-T 1020, 2 isolates) and by 1 or 2 bp from the B. cepacia genomovar III LMG 12614 sequence (C-T 1008, 2 isolates; C-T 1008 and T-C 1020, 1 isolate). They differed by >5 bp from the sequences of the other members of the B. cepacia complex. The fourth isolate was identified as B. vietnamiensis. This isolate had a sequence identical to that of B. vietnamiensis TVV75T. Its sequence differed from those of the other members of the B. cepacia complex by 4 to >10 bp. The fifth isolate was identified as B. gladioli. This isolate had a sequence identical to that of B. gladioli ATCC 10248T, differing by 1 bp from that of B. cocovenenans LMG 11626T (G-A 1009) and by 5 bp from that of B. plantarii LMG 9035T. Its sequence differed from those of other Burkholderia species by more than 10 bp. Finally, 3 isolates (2 patients), with identical 16SRNA sequences, were identified as Ralstonia pickettii biovar 3/“thomasii,” which was recently classified as a separate species, R. mannitolilytica, originally described as R. mannitolytica (8). These isolates had a sequence identical to that of R. pickettii biovar 3/“thomasii” LBV 407 and different from that of R. pickettii biovar 3/“thomasii” LMG 6866T by 1 bp (A-G 1250). The sequences from R. solanacearum (>5-bp difference), R. pickettii (≥10-bp difference), and other Ralstonia species (>35-bp difference) were much less similar. The positions of CF Burkholderia and Ralstonia isolates are shown in an unrooted phylogenetic tree based upon partial 16S DNA sequences from reference strains (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Position of CF Burkholderia and Ralstonia isolates. The bar indicates 10% estimated sequence divergence. Clinical isolates are designated by their laboratory number.

Around 5% of the nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli isolated from the patients attending our CF center could not be identified satisfactorily in routine laboratory tests. When tested with the API 20NE system, despite the superior performance of this test with respect to the other commercial identification system (22), 75% of these isolates gave an unknown profile and 25% were misidentified. The commonest misidentifications were the identification of P. aeruginosa, S. maltophilia, and A. xylosoxidans isolates as B. cepacia. This was particularly misleading, as most of these isolates were recovered on B. cepacia-selective medium and were resistant to colistin (data not shown). Other authors have reported misidentification frequencies of 4 to 50% with CF isolates of B. cepacia (12, 16, 18), Stenotrophomonas sp. (3), and Alcaligenes sp. (17). We were able to identify most isolates to the species level by 16S DNA sequencing. However, as previously reported, the 16S rRNA gene was not variable enough to discriminate between closely related species such as B. cepacia genomovars I and III (14, 18) or to differentiate accurately between the subspecies of A. xylosoxidans.

The use of 16S DNA sequencing gave us no real new insight into the overall epidemiological pattern of CF pathogens at our center. As expected, most of the problematic isolates were P. aeruginosa, with A. xylosoxidans, S. maltophilia, and Burkholderia spp. considerably less abundant. However, one novel finding was the identification of three isolates recovered from two children as R. mannitolilytica. To our knowledge, this species has not previously been isolated from CF patients, but it may have been confused with related species such as R. pickettii. Based on the cases considered here, R. mannitolilytica does not appear to have a high potential for pathogenesis. One of our patients had a very mild CF lung disease and the other had a severe lung disease but had been colonized with P. aeruginosa for years and had received a number of intravenous treatments for this P. aeruginosa colonization. Further studies of a larger number of individuals are required to determine whether R. mannitolilytica should be considered an emerging CF pathogen.

The identification provided by 16S DNA sequencing had clear management implications in three cases. In one patient, R. mannitolilytica was previously misidentified as B. cepacia and this had led to the implementation of drastic control measures. Once the bacterium had been identified as R. mannitolilytica, these measures were restricted to the precautions taken routinely with any multiresistant organism at our center. Conversely, infection with B. cepacia genomovar I/III was previously undetected in another patient who had suffered severe unexplained pulmonary deterioration over the last few months. This patient was in the process of developing a B. cepacia syndrome, which had gone unrecognized before identification with 16S DNA sequencing. This patient died within a few months despite treatment, but the recognition of this case made it possible to take apparently efficient control measures to prevent the dissemination of the bacterium to other patients. Finally, the diagnosis of S. maltophilia colonization in a third patient made it possible to replace the classical anti-Pseudomonas treatment given to the patient by more appropriate antibiotics, including the trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole combination.

This study confirms the value of DNA-based methods for the identification of nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli recovered from CF patients, especially organisms identified as B. cepacia or related species. Our study also suggests that the use of DNA-based identification methods has a small but significant impact on the clinical management of CF patients, which should be investigated in studies in other CF centers.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christine Segonds (Hôpital Rangueil, Toulouse, France) for providing strains, Marie-Laure Chaix (Hôpital Necker-Enfants Malades, Paris, France) for help in the construction of phylogenetic trees, and Marianne Villier (Hôpital Raymond Poincaré, Garches, France) for help with the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bauernfeind, A., I. Schneider, R. Jungwirth, and C. Roller. 1998. Discrimination of Burkholderia gladioli from other Burkholderia species detectable in cystic fibrosis patients by PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2748-2751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauernfeind, A., I. Schneider, R. Jungwirth, and C. Roller. 1999. Discrimination of Burkholderia multivorans and Burkholderia vietnamiensis from Burkholderia cepacia genomovars I, III, and IV by PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1335-1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burdge, D. R., M. A. Noble, M. E. Campbell, V. L. Krell, and D. P. Speert. 1995. Xanthomonas maltophilia misidentified as Pseudomonas cepacia in cultures of sputum from patients with cystic fibrosis: a diagnostic pitfall with major clinical implications. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2:445-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burns, J. L., J. Emerson, J. R. Stapp, D. L. Yim, Y. J. Krzewinski, L. Louden, B. W. Ramsey, and C. R. Clausen. 1998. Microbiology of sputum from patients at cystic fibrosis centers in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 27:158-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clode, F. E., M. E. Kaufmann, H. Malnick, and T. L. Pitt. 1999. Evaluation of three oligonucleotide primer sets in PCR for the identification of Burkholderia cepacia and their differentiation from Burkholderia gladioli. J. Clin. Pathol. 52:173-176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coenye, T., E. Mahenthiralingam, D. Henry, J. J. Lipuma, S. Laevens, M. Gillis, D. P. Speert, and P. Vandamme. 2001. Burkholdria ambifaria sp. nov., a novel member of the Burkholderia cepacia complex including biocontrol and cystic fibrosis-related isolates. Int. J. Syst. E vol. Microbiol. 51:1481-1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coenye, T., L. M. Schouls, J. R. W. Govan, K. Kersters, and P. Vandamme. 1999. Identification of Burkholderia species and genomovars from cystic fibrosis patients by AFLP fingerprinting. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49:1657-1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Baere, T., S. Steyaert, G. Wauters, P. De Vos, J. Goris, T. Coenye, G. Suyama, G. Verschraegen, and M. Vaneechoutte. 2001. Classification of Ralstonia picketti biovar 3/“thomasii” strains (Pickett, 1994) and of new isolates related to nosocomial recurrent meningitis as Ralstonia mannitolytica sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. E vol. Microbiol. 51:547-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fegan, M., P. Francis, A. C. Hayward, G. H. Davis, and J. A. Fuerst. 1990. Phenotypic conversion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:1143-1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghozzi, R., P. Morand, A. Ferroni, J. L. Beretti, E. Bingen, C. Segonds, M. O. Husson, D. Izard, P. Berche, and J. L. Gaillard. 1999. Capillary electrophoresis-single-strand conformation polymorphism analysis for rapid identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other gram-negative nonfermenting bacilli recovered from patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3374-3379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilligan, P. H. 1991. Microbiology of airway disease in patients with cystic fibrosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 4:33-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henry, D. A., M. E. Campbell, J. J. LiPuma, and P. Speert. 1997. Identification of Burkholderia cepacia isolates from patients with cystic fibrosis and use of a simple new selective medium. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:614-619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LiPuma, J. J., B. J. Dulaney, J. D. McMennamin, P. W. Whitby, T. L. Stull, T. Coenye, and P. Vandamme. 1999. Development of rRNA-based PCR assays for identification of Burkholderia cepacia complex isolates recovered from cystic fibrosis patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3167-3170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahenthiralingam, E., J. Bischof, S. K. Byrne, C. Radomski, J. E. Davies, Y. Av-Gay, and P. Vandamme. 2000. DNA-based diagnostic approaches for identification of Burkholderia cepacia complex, Burkholderia vietnamiensis, Burkholderia multivorans, Burkholderia stabilis, and Burkholderia cepacia genomovars I and III. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3165-3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McDowell, A., E. Mahenthiralingam, J. E. Moore, K. E. A. Dunbar, A. K. Webb, M. E. Dodd, S. L. Martin, B. C. Millar, C. J. Scott, M. Crowe, and, J. S. Elborn. 2001. PCR-based detection and identification of Burkholderia cepacia complex pathogens in sputum from cystic fibrosis patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4247-4255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McMenamin, J. D., T. M. Zaccone, T. Coenye, P. Vandamme, and J. J. LiPuma. 2000. Misidentification of Burkholderia cepacia in US cystic fibrosis treatment centers. An analysis of 1,051 recent sputum isolates. Chest 117:1661-1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saiman, L., Y. Chen, S. Tabibi, P. San Gabriel, J. Zhou, Z. Liu, L. Lai, and S. Whittier. 2001. Identification and antimicrobial susceptibility of Alcaligenes xylosoxidans isolated from patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3942-3947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Segonds, C., T. Heulin, N. Marty, and G. Chabanon. 1999. Differentiation of Burkholderia species by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the 16S rRNA gene and application to cystic fibrosis isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2201-2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shelly, D. B., T. Spilker, E. J. Gracely, T. Coenye, P. Vandamme, and J. J. Lipuma. 2000. Utility of commercial systems for identification of Burkholderia cepacia complex from cystic fibrosis sputum culture. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3112-3115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shigei, J. 1992. Test methods used in the identification of commonly isolated aerobic gram-negative bacteria, p. 1-104. In H. D. Isenberg (ed.), Clinical microbiology procedures handbook, vol. 1. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 21.Shreve, M. R., S. Butler, H. J. Kaplowitz, H. R. Rabin, D. Stokes, M. Light, W. E. Regelmann, et al. 1999. Impact of microbiology practice on cumulative prevalence of respiratory tract bacteria in patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:753-757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Pelt, C., C. M. Verdun, W. H. F. Goessens, M. C. Vos, B. Tummler, C. Segonds, F. Reubsaet, H. Verbrugh, and A. Van Belkum. 1999. Identification of Burkholderia spp. in the clinical microbiology laboratory: comparison of conventional and molecular methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2158-2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whitby, P. W., L. C. Pope, K. B. Carter, J. J. LiPuma, and T. L. Stull. 2000. Species-specific PCR as a tool for the identification of Burkholderia gladioli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:282-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]