Abstract

The phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains fluctuate over time both locally and globally, and highly discriminative and precise characterization of the strains is essential. Conventional characterization of N. gonorrhoeae strains for epidemiological purposes is mostly based on phenotypic methods, which have some inherent limitations. In the present study sequence analysis of porB1b gene sequences was used for examination of the genetic relationships among N. gonorrhoeae strains. Substantial genetic heterogeneity was identified in the porB genes of serovar IB-2 isolates (8.1% of the nucleotide sites were polymorphic) and serovar IB-3 isolates (5.2% of the nucleotide sites were polymorphic) as well as between isolates of different serovars. The highest degree of diversity was identified in the gene segments encoding the surface-exposed loops of the mature PorB protein. Phylogenetic analysis of the porB1b gene sequences confirmed previous findings that have indicated the circulation of one N. gonorrhoeae strain each of serovar IB-2 and serovar IB-3 in the Swedish community. These strains caused the majority of the cases in two domestic core groups comprising homosexual men and young heterosexuals, respectively, and were also detected in other patients. The phylogenetic analyses of porB gene sequences in the present study showed congruence, but not complete identity, with previous results obtained by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of the same isolates. In conclusion, porB gene sequencing can be used as a molecular epidemiological tool for examination of genetic relationships among emerging and circulating N. gonorrhoeae strains, as well as for confirmation or discrimination of clusters of gonorrhea cases.

Neisseria gonorrhoeae is the etiological agent of gonorrhea, which remains a major sexually transmitted infection worldwide (20). In the absence of an effective vaccine for N. gonorrhoeae infections, the mainstay in the prevention of infection is based on regional, national, and international surveillance of the epidemiological characteristics as well as the antibiotic susceptibilities of the bacteria. The phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of N. gonorrhoeae strains fluctuate over time both locally and globally, and highly discriminative and precise characterization of the strains is essential. This can increase the level of knowledge about the strain populations circulating in the community, temporal and geographic changes among strains, as well as the emergence and spread of certain strains, information that is crucial for the development of improved control measures. Conventional characterization of N. gonorrhoeae strains for epidemiological and clinical purposes is mostly based on auxotyping, serovar designation, and antibiograms. However, these phenotypic systems have some inherent limitations concerning, for instance, their discriminatory abilities and reproducibilities (12, 14, 15, 18, 27). Different DNA-based methods have thus been developed (14, 19, 26, 28, 29, 30, 33).

In the present study, sequencing of the porB gene was used for molecular characterization of N. gonorrhoeae isolates. The antigenic expression of outer membrane protein PorB within a strain is stable; diversities between strains form the basis for serogroup and serovar determination with monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) (16, 24). Any individual N. gonorrhoeae strain expresses only one of two different groups of the porin proteins PorB1a and PorB1b, which show high degrees of sequence homology (6, 8, 13, 32). The proteins are encoded by the mutually exclusive alleles of the porB gene, porB1a and porB1b, respectively (8, 13).

Since 1997 the incidence of gonorrhea in Sweden has been increasing, mostly due to a significant increase in the numbers of domestic cases (1). In a 1-year prevalence study conducted during this increase, clinical and epidemiological data were prospectively obtained for all cases of gonorrhea reported in Sweden and the N. gonorrhoeae isolates were phenotypically characterized (1, 2). Two core groups with domestic cases were identified: homosexual men in whom N. gonorrhoeae serovar IB-2 was the most prevalent serological variant and young heterosexuals of both sexes in whom serovar IB-3 was the most prevalent serological variant (1). Genetic examination by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) indicated that two N. gonorrhoeae strains of the predominant serovars, serovars IB-2 and IB-3, respectively, caused the majority of the cases in the two domestic groups (30).

The aims of the present study were to investigate the genetic heterogeneity in the porB genes of N. gonorrhoeae reference strains of different serovars and to examine the genetic diversity in the porB1b genes of the predominant Swedish serovars, serovars IB-2 and IB-3, as well as to evaluate (by phylogenetic analysis) the porB1b gene sequences for examination of the genetic relationships between the strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates and culture conditions.

In the present study eight N. gonorrhoeae reference strains representing different serovars (see Fig. 1), clinical isolates of the two predominant serovars in the national study (1), serovars IB-2 (n = 40) (see Fig. 2) and IB-3 (n = 68) (see Fig. 3), as well as multiple isolates from five patients (n = 10) were examined. Consequently, a total of 126 N. gonorrhoeae isolates were analyzed.

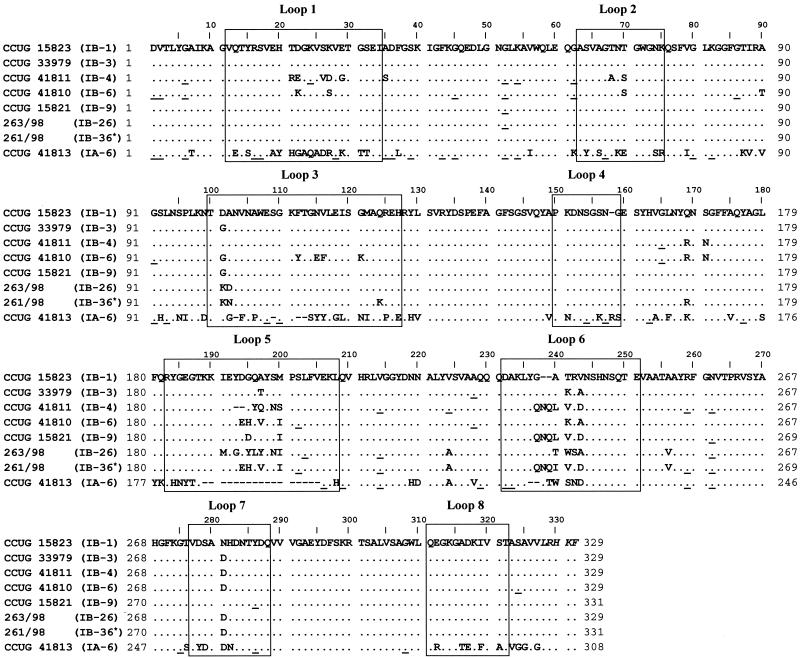

FIG. 1.

Multiple alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences of the mature PorB proteins (with the 19-amino-acid signal peptide excluded) of eight N. gonorrhoeae reference strains of different serovars. Dots denote identity with the PorB1b amino acid sequence of strain CCUG 15823, dashes represent alignment gaps, and underlining denotes synonymous substitutions. The boxes mark the sequences of the surface-exposed loops predicted according to the model of van der Ley et al. (32). Amino acids in italics at the C terminus were specified in one of the sequencing primers. ∗, the isolate was reactive with MAbs 3C8, 1F5, 2G2, 2D4, and 2H1 and was designated as being of serovar IB-36 in the present study.

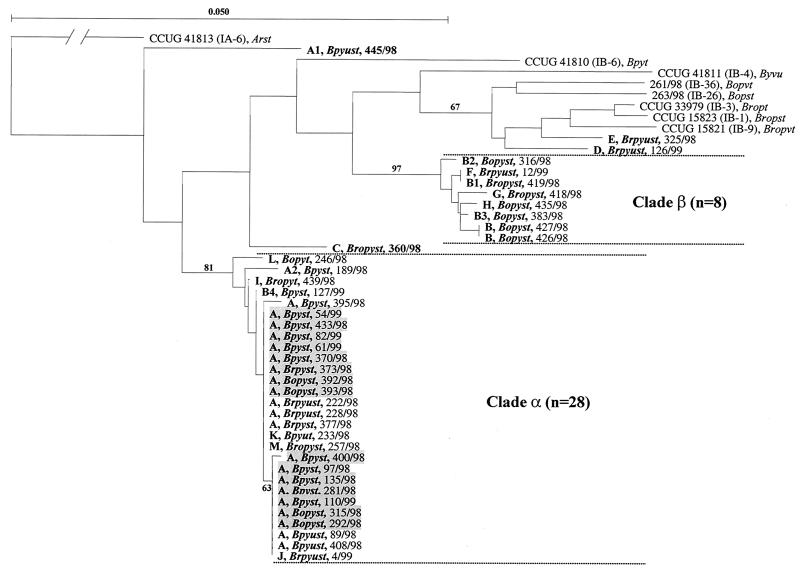

FIG. 2.

Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree describing the evolutionary relationships of porB1b gene sequences (999 unambiguously aligned nucleotides) coding for the mature porin of clinical N. gonorrhoeae serovar IB-2 isolates (n = 40). Eight reference strains were included, and the porB1a sequence of reference strain CCUG 41813 (serovar IA-6), which represents an outgroup, was used to root the tree. The length of the branch leading to the outgroup has been reduced by a factor of 10. The different PFGE types and variants (less than four band differences in both the SpeI and the BglII PFGE fingerprints [30]) of the IB-2 isolates are indicated by boldface capital letters. The serovars of the isolates obtained with Ph MAbs are indicated by boldface italics, the isolates of PFGE type A that originated in the Swedish domestic serovar IB-2 core group from homosexual men are shaded, and the strain designations are also included. Relevant bootstrap values (as a percentage of 1,000 resamplings) are also shown.

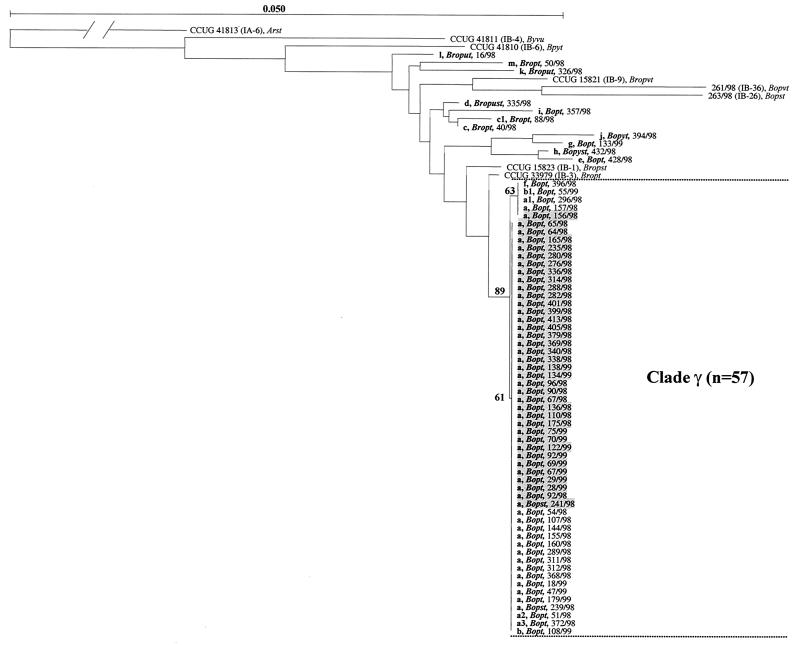

FIG. 3.

Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree describing the evolutionary relationships of porB1b gene sequences (999 unambiguously aligned nucleotides) coding for the mature porin of clinical N. gonorrhoeae serovar IB-3 isolates (n = 68). Eight reference strains were included, and the porB1a sequence of reference strain CCUG 41813 (serovar IA-6), which represents an outgroup, was used to root the tree. The length of the branch leading to the outgroup has been reduced by a factor of 10. The different PFGE types and variants (less than four band differences in both the SpeI and the BglII PFGE fingerprints [30]) of the IB-3 isolates are indicated by boldface lowercase letters. The serovars of the isolates obtained with Ph MAbs are indicated by boldface italics, the isolates with PFGE type a that originated in the Swedish domestic serovar IB-3 core group from young heterosexuals are shaded, and the strain designations are also included. Relevant bootstrap values (as a percentage of 1,000 resamplings) are also shown.

The selection of the isolates of serovars IB-2 and IB-3 and the multiple isolates was based on the results obtained in a previous study (30). All isolates of two major N. gonorrhoeae clusters comprising phenotypically and genetically indistinguishable (no band difference by PFGE) IB-2 isolates (n = 21) and IB-3 isolates (n = 51), respectively, as well as IB-2 isolates (n = 19) and IB-3 isolates (n = 17) with distinguishable PFGE fingerprints (any band difference) from the two clusters of fingerprints (30) were included in the present study. Isolates (n = 8) from four patients infected with two distinguishable strains according to previous PFGE results as well as two genetically and phenotypically identical isolates (with the exception of β-lactamase production) from one additional patient (30) were also included.

All isolates were cultured on GCSPP agar (3% GC medium base [Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.], 1% supplements [40% d-glucose, 1% l-glutamine, 0.01% cocarboxylase, 0.05% ferric nitrate], and 0.5% IsoVitaleX enrichment [BBL, Becton Dickinson and Company, Cockeysville, Md.]) at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 18 to 20 h and preserved at −70°C.

Serological characterization.

Serotyping of all isolates was performed by a coagglutination technique (24) with the Pharmacia panel (Ph) (25) as well as the Genetic Systems (GS) panel (16) of MAbs.

Isolation of genomic DNA.

Cultured bacteria were suspended in sterile 0.15 M NaCl to a concentration of approximately 3 × 108 cells/ml. A total of 500 μl from each suspension was pelleted and resuspended in 10 μl of sterile distilled water. DNA was isolated with the Dynabeads DNA DIRECT Universal kit (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) according to the instructions of the manufacturer with the following optimizations: the samples were incubated at 65°C for 15 min with Dynabeads to improve lysis of the bacteria, and the DNA was eluted from the beads during incubation at 65°C for 5 min. The DNA preparations were stored at 4°C prior to PCR.

forB PCR.

Primers PorBU and PorBL (Table 1) were used for amplification of the entire porB gene. The PCR mixture (50 μl) contained 1.0 U of AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.), 1× PCR Gold buffer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.), 2.5 mM MgCl2 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.), 0.1 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.), and 0.5 μM concentrations of each primer. The mixture was overlaid with 50 μl of mineral oil, 1 μl of the genomic DNA template was added, and the PCR was run in a PTC-100 instrument (MJ Research, Watertown, Mass.). The amplification was performed by using the following cycling parameters: an enzyme activation step at 94°C for 10 min, followed by 30 sequential cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 90 s. At the end of the final cycle, an extension phase at 72°C for 4 min was included before storage at 4°C. A positive control (DNA of an N. gonorrhoeae reference strain, CCUG 15821) and a negative control (distilled water) were included in each PCR run. The products were analyzed by electrophoresis through a 2% agarose gel and ethidium bromide staining. DNA Molecular Weight Marker VI (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) was included on each gel for determination of the sizes of the amplicons.

TABLE 1.

Primers used in the PCR and sequencing of porB gene

| Primera | Sequence (5′ → 3′) | Use | Nucleotide location | Source (reference) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PorBU | CCGGCCTGCTTAAATTTCTTA | PCR and sequencing | 30-50b,c | Shortened PorI (14) |

| PorBL | ATTAGAATTTGTGGCGCAG | PCR and sequencing | 1118-1100b,d | Shortened PorII (14) |

| PorB1bU | CCGCTACCTGTCCGTACGC | Sequencing | 508-526b | Shortened porseq1 (14) |

| PorB1bL | GAACAAGCCGGCGTATTGTG | Sequencing | 667-648b | Shortened porseq2 (14) |

| PorB1aU | CGTACGCTACGATTCTCCCG | Sequencing | 521-540e | Shortened porseq3 (14) |

| PorB1aL | CATATTGCACGAAGAAGCCGC | Sequencing | 657-637e | Shortened porseq4 (14) |

DNA sequencing.

The primers used for sequencing of the amplified porB gene are shown in Table 1. The PCR products were purified with the High Pure PCR product purification kit (Roche Diagnostics) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Each cycle sequencing mixture (5 μl) contained 2 μl of the reagents supplied with the ABI BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom), one of the primers at a concentration of 0.32 μM, and 1 μl of the purified PCR product. The sequence extension products were purified by using the DyeEx Spin kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the instructions of the manufacturer, and the nucleotide sequences were determined by using an ABI PRISM 310 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). The sequence of each strand of each compiled sequence was determined at least once.

Phylogenetic inference.

Multiple-sequence alignments of the gene segments encoding the mature PorB proteins were performed with BioEdit (version 5.0.9) software and by manual adjustment. Phylogenetic trees were constructed with a parallel version of DNAml (maximum-likelihood method) (5) in the PHYLIP (version 3.52c) package with the F84 substitution model, empirical nucleotide frequencies, a transition/transversion ratio of 2.0 (F84), and the global rearrangements option on (10). The DNAml analysis was performed under Linux on a custom-built Beowulf cluster, consisting of one master and four slaves. Trees were also constructed by using TREECON (version 1.3b) software by using the Jin and Nei substitution model, the Kimura evolutionary model, an α value of 0.5 (31), and the neighbor-joining method. Bootstrap analysis (9) with 1,000 resamplings was performed by using TREECON software with the same settings described above. The porB1a sequence of reference strain CCUG 41813 (serovar IA-6) was used as an outgroup to root the tree. The alignment was not stripped of gaps before phylogenetic analysis because most indels were unique to the outgroup sequence and occurred in the variable loops. Thus, important phylogeny would have been lost if gap-stripping had been done.

RESULTS

Sequencing of porB genes from reference strains (n = 8).

Ninety-one percent of the nucleotides in the segments of the porB gene encoding the mature protein were conserved in the porB1b reference strains (n = 7), and the sequence encoding the mature protein in the porB1a strain (CCUG 41813 [serovar IA-6]) had 72% homology with the consensus sequence of the porB1b strains. The porB1a gene (924 nucleotides) was 63 to 69 nucleotides smaller than the porB1b gene (987 to 993 nucleotides), mostly due to the shorter gene segment encoding the predicted surface-exposed amino acid loop 5 in the mature protein, according to the model of van der Ley et al. (32) (Fig. 1).

The heterogeneity in the porB1b genes was most pronounced in the segments encoding the loops of the porin, which exhibited 65 polymorphic nucleotide sites (15.1 per 100 sites), whereas the regions encoding sequences between the surface-exposed loops exhibited 23 polymorphic nucleotide sites (4.1 per 100 sites). Nonsynonymous substitutions (mutations that resulted in amino acid replacements) were more prevalent in the segments encoding the loops (n = 61 sites; 14.2 per 100 sites) than in the sequences not encoding the loops (n = 7 sites; 1.2 per 100 sites). Synonymous (silent) substitutions were in preponderance in the segments encoding sequences between the loops (n = 16 sites; 2.8 per 100 sites) in comparison to their prevalence in segments within the loops (n = 4 sites; 0.9 per 100 sites). Gene segments encoding loops 1 (17% of the nucleotide sites were polymorphic), 3 (16%), 5 (27%), and 6 (25%) of the proteins were the most heterogeneous ones, whereas regions encoding loops 2 (5% of the nucleotide sites were polymorphic), 4 (0%), 7 (6%), and 8 (0%) were more conserved (Fig. 1).

Sequencing of porB1b genes from IB-2 isolates (n = 40).

In the alignment of the serovar IB-2 porB1b sequences, a total of 80 (8.1%) polymorphic sites were identified. Gene segments encoding the loops exhibited 58 polymorphic sites (13.6 per 100 sites), and regions encoding the sequences between the loops exhibited 22 polymorphic sites (3.9 per 100 sites). Nonsynonymous substitutions were more prevalent in the segments encoding the loops (n = 54 sites; 12.7 per 100 sites) than in the sequences not encoding the loops (n = 10 sites; 1.8 per 100 sites). The deduced amino acid sequences contained 33 (23.2%) heterogeneous sites in the predicted loops and 9 (4.8%) heterogeneous sites between the loops. The frequency of synonymous substitutions was low and similar in the segments encoding sequences between the loops (n = 12 sites; 2.1 per 100 sites) and within the loops (n = 4 sites; 0.9 per 100 sites). The regions of the porB1b gene encoding loops 1 (17% of the nucleotide sites were polymorphic), 3 (17%), 5 (15%), 6 (13%), 7 (17%), and 8 (15%) of the proteins exhibited the most heterogeneity, whereas regions encoding loops 2 (0% of the nucleotide sites were polymorphic) and 4 (4%) were more conserved.

The 40 IB-2 isolates comprised 13 different PFGE types (variants included; 19 distinguishable fingerprints) and 18 unique porB1b gene sequences (Fig. 2). The phylogenetic tree analysis revealed that 36 of the porB1b gene sequences from these 40 isolates fell into two major sequence clades (clades α and β), whereas four sequences were quite distantly related to each other as well as to the sequences in clades α and β (isolates 445/98, 360/98, 126/99, and 325/98) (Fig. 2).

Overall, the results of PFGE and porB1b sequencing showed congruence but not complete identity. Thus, clade α included all isolates of PFGE type A or variants of type A except isolate 445/98. However, clade α also comprised a single isolate each of PFGE types B4, I, J, K, L, and M. Similarly, clade β included all isolates of PFGE type B or variants of type B except isolate 127/99. Clade β also comprised isolates of PFGE types F, G, and H (Fig. 2).

Twenty-one isolates had indistinguishable PFGE fingerprints (type A) but displayed four slightly different porB1b sequences (Fig. 2). The phylogenetic analysis suggested that this represented the ongoing evolution of the porB1b genes of these isolates. Thus, compared to 11 identical porB1b “core” sequences in isolates of PFGE type A (Fig. 2), nine isolates had acquired a single G→A nucleotide substitution at site 577, which caused a D→N amino acid replacement in loop 5. One of these nine isolates (isolate 400/98) had acquired an additional substitution (T817→A). Finally, one isolate (isolate 395/98) had two nucleotide transitions (A62→G and G595→A) in comparison with the 11 core sequences that resulted in a Q→R replacement in loop 1 and a V→I replacement in loop 5, respectively (Fig. 2).

Serovar determination with the Ph MAbs identified five different serovars among the IB-2 isolates of PFGE type A (n = 21) and two additional different serovars among the isolates of PFGE types K and M. Consequently, six different serovars could be identified by use of Ph MAbs (Ph serovars) among only 13 isolates belonging to clade α and displaying identical porB1b sequences (Fig. 2). Notably, four of the five isolates of PFGE type B or variants of type B in clade β belonged to the same Ph serovar (Bopyst), and the four isolates that were distantly related to the ones in clades α and β (isolates 445/98, 360/98, 126/99, and 325/98) were of Ph serovars identical to those of several of the isolates within the clades (Fig. 2).

One presumed cluster (n = 4) comprising isolates of serovar IB-2 derived from the domestic cluster of homosexual men with known epidemiological connections was included among the IB-2 isolates. All four isolates (isolates 426/98, 427/98, 392/98, and 393/98) reacted as the same Ph serovar (serovar Bopyst) (Fig. 2). The sequencing of the porB1b genes of these isolates, however, discriminated the isolates into two pairs of identical isolates belonging to clade α and clade β, respectively, which exhibited 38 nucleotide differences in the porB1b genes (Fig. 2).

Sequencing of porB1b genes from IB-3 isolates (n = 68).

A total of 51 (5.2%) polymorphic sites existed in the alignment of the serovar IB-3 porB1b sequences. Segments of the gene encoding the loops exhibited 34 polymorphic sites (8.0 per 100 sites), and regions encoding sequences between the loops exhibited 17 polymorphic sites (3.0 per 100 sites). Nonsynonymous substitutions were more prevalent in the segments encoding the loops (n = 33 sites; 7.7 per 100 sites) than in the sequences not encoding the loops (n = 5 sites; 0.9 per 100 sites). The deduced amino acid sequences contained 21 (14.8%) heterogeneous sites in the predicted loops and 5 (2.7%) heterogeneous sites between the loops. The prevalence of synonymous substitutions was low, with such substitutions predominating in the segments encoding the sequences between the loops (n = 12 sites; 2.1 per 100 sites) in comparison to the prevalence in the segments within the loops (n = 1 site; 0.2 per 100 sites). The segments of the porB1b gene encoding loops 3 (8.3% of the nucleotide sites were polymorphic), 5 (19.8%), 6 (7.4%), and 7 (8.3%) of the proteins exhibited the most heterogeneity, whereas regions encoding loops 1 (4.3% of the nucleotide sites were polymorphic), 2 (0%), 4 (0%), and 8 (2.8%) were more homologous.

The 68 serovar IB-3 isolates comprised 13 different PFGE types (variants included; 18 distinguishable fingerprints) and 13 unique porB1b gene sequences (Fig. 3 ). The phylogenetic analysis showed that 57 of the porB1b sequences from these 68 isolates belonged to one major sequence clade (clade γ), whereas 11 sequences were quite distantly related to the sequences in clade γ (Fig. 3). Most of the distantly related sequences (64%) were those of isolates from heterosexuals exposed abroad.

Overall, the results of PFGE and porB1b sequencing showed congruence; however, some exceptions existed. Thus, clade γ included all isolates of PFGE type a or variants of type a. Clade γ, however, also comprised a single isolate each of PFGE types b, b1, and f (Fig. 3).

Fifty-one isolates displayed indistinguishable PFGE fingerprints (type a) but had two unique porB1b sequences. However, compared to the 49 core sequences, the porB1b sequences of two epidemiologically linked isolates (isolates 156/98 and 157/98) had acquired a single nucleotide transition (G584→A) coding for a G→D amino acid replacement in loop 5 (Fig. 3).

The serological characterization with Ph MAbs designated 49 of the isolates of PFGE type a as serovar Bopt; however, two isolates were distinguished as serovar Bopst. Notably, three of the isolates that were distantly related to the ones in clade γ also belonged to serovar Bopt (Fig. 3).

Among the serovar IB-3 isolates, strains from four suspected clusters (n = 2, n = 2, n = 3, and n = 6, respectively) of gonorrhea cases among young heterosexuals were included. All the patients were exposed in the same small town in Sweden, and the individuals in the respective clusters exhibited evident epidemiological connections. Sequencing of the porB1b gene revealed that all isolates (n = 13) from the four suspected clusters had identical DNA sequences. All the isolates belonged to clade γ and showed identical reactivities with the Ph MAbs (serovar Bopt).

Sequencing of porB genes from multiple isolates from the same patient (n = 5).

For three of the patients whose isolates were distinguishable by PFGE (30), both isolates from each patient exhibited identical porB gene sequences as well as belonged to the same serovars according to their reactivities with the GS and Ph MAbs. porB sequencing, however, confirmed that the fourth patient was infected with two different strains (exhibiting 44 nucleotide differences in the porB1b gene sequences). Serovar determination also distinguished the two isolates as the Ph serovars Brpyut and Brpyust and GS serovars IB-6 and IB-33, respectively. In the case of a patient carrying two isolates that differed only by β-lactamase production, the porB1b gene sequences of the isolates as well as their GS and Ph serovars were identical.

DISCUSSION

Sequencing of the porB gene confirmed previous findings that have indicated the emergence and circulation of one N. gonorrhoeae strain each of serovar IB-2 and serovar IB-3 in the Swedish community. The spread of the strains caused the majority of the cases in two epidemiologically identified domestic core groups: homosexual men and young heterosexuals, respectively (30). The strains were also detected in other patients. Detailed sequence analysis, however, identified some limited variations in the porB1b genes of isolates of the strains. Despite this heterogeneity (one to four nucleotide substitutions), the isolates were considered to belong to the same strain on the basis of porB gene sequencing together with background knowledge of their indistinguishable PFGE fingerprints (30) and identical reactivities with the GS MAbs by serotyping. PorB is considered antigenically stable during the course of infection in smaller groups of sexual contacts (35). However, the protein has shown antigenic variation over time, as revealed by the diversity of serovars (21) and porB genes (11) identified in the N. gonorrhoeae isolates derived from patients in sexual networks. Sequence analysis of porB genes has previously indicated the presence of horizontal genetic exchange, including the exchange of the entire gene or segments of the gene, as well as point mutations in the evolution of the porin during circulation within the community (3, 11, 14, 23). However, more knowledge concerning the mechanisms and time scale by which changes in the porB genes occur is required. In isolates derived from patients of a core group, in which the immune response may continuously select new antigenic variants of PorB, the evolution of the porB gene seems to be influenced by a mosaicism among porB gene sequences that is more prevalent than that in isolates from other patients (11). However, point mutations in the gene may not be more prevalent (11). In these core groups, diversification of the gene may be necessary for the survival and ecological success of N. gonorrhoeae in the host (11). Accordingly, the minor genetic changes in the porB1b gene in isolates of the strains probably reflect the ongoing evolution of the gene, as the phylogenetic analysis suggested. Serovar determination with Ph MAbs, however, identified five different serovars among the isolates of the serovar IB-2 strain and two different serovars among the isolates of the serovar IB-3 strain. Furthermore, six different Ph serovars were identified among only 13 serovar IB-2 isolates, all of which exhibited identical porB1b sequences. Thus, serovar determination with Ph MAbs discriminated isolates designated as the same serovar with GS MAbs, as described previously (18, 25). However, isolates exhibiting identical porB1b sequences were assigned to different serovars with Ph MAbs, differing from one another in their reactivities with one to two MAbs. These discrepancies may reflect reproducibility problems due to a suboptimal quality or interbatch variations in the MAb reagents used, a subjective interpretation of the coagglutination reaction, other methodological problems, or perhaps accessibility problems for some antigenic epitopes due to the conformational effects of native PorB (7, 12, 15, 17, 22).

By sequencing the porB gene of N. gonorrhoeae isolates, it is possible to characterize suspected clusters of gonorrhea cases or confirm presumed epidemiological connections of patients (7, 34). In the present study, porB sequencing as well as serological characterization with Ph MAbs discriminated one suspected serovar IB-2 cluster as well as confirmed the existence of three serovar IB-3 clusters, findings in concordance with previous PFGE results (30). Neither porB sequencing nor serological characterization with Ph MAbs, however, was able to discriminate the isolates of the fourth presumed serovar IB-3 cluster (n = 2). These isolates were previously distinguished by use of their PFGE fingerprints, which differed by five bands (30). Consequently, 12 of the isolates from the four suspected serovar IB-3 clusters (n = 13) exhibited identical porB1b sequences, indistinguishable PFGE fingerprints, as well as identical phenotypes. This, together with exposure of the patients in the same geographic district, might indicate the existence of one larger cluster of gonorrhea cases among young heterosexuals in the small Swedish town.

For three of the patients infected with multiple distinguishable strains according to PFGE analysis (30), the results could not be confirmed by porB gene sequencing or serovar determination with Ph MAbs. The strains were, however, considered closely related by PFGE (30). One possibility is that these are the same strains but only one genetic event, i.e., a point mutation or recombination, has occurred within the bacterial genome of one of the isolates. porB gene sequencing as well as serovar determination with Ph MAbs, however, confirmed previous results (30) that a fourth patient was infected with two different strains that were isolated on the same occasion. For the one patient infected with multiple isolates, the theory that the patient was infected with multiple isolates of a strain in which one isolate had lost the β-lactamase plasmid was also strengthened by the identical porB gene sequences as well as the identical Ph serovars.

Overall, the results of phylogenetic analysis of the porB gene sequences in the present study showed congruence, but not complete identity, with previous results obtained by PFGE of the same isolates (30). This lack of complete congruence between the methods is in full agreement with the results of other studies (7, 22, 34). Phylogenetic analysis suggested that some discrepant isolates in clades α, β, and γ might be more closely related than the level of relatedness revealed by PFGE. Alternatively, the divergent PFGE fingerprints in the isolates may reflect the occurrence of point mutations or recombination that caused a distinct evolutionary history in the porB1b gene in comparison to other parts of the genome. The results of PFGE and phylogenetic analysis for two IB-2 isolates (isolates 445/98 and 127/99) showed more dramatic disagreement and may indicate that the isolates are recombinants or may even reflect misclassification by one of the methods. No restriction sites for the enzymes SpeI and BglII, used for PFGE (30), existed in the porB1b genes of the isolates examined. By sequencing a single important genetic locus, the porB gene, the molecular characterization of the isolates was refined in the present study, and this analysis forms a useful complement to PFGE, which potentially indexes the entire genome. porB gene sequencing exhibited a high discriminatory ability and a high degree of typeability (all 126 isolates were typeable). In addition, the method gave more reliable information than serological characterization and did not require MAbs that may have limited availability. Sequence data are also objective and portable for comparison between laboratories. However, no information concerning the exposure of immunologically important epitopes was obtained. This fact, as well as the time-consuming nature of the procedure and the need for sophisticated and expensive equipment, is, at least for the present, a limitation of sequencing.

In conclusion, porB gene sequencing can be used as a molecular epidemiological tool for examination of genetic relationships among emerging and circulating N. gonorrhoeae strains, for confirmation or discrimination of clusters of gonorrhea cases, and perhaps also for monitoring of the evolution of the porB gene over time during passage within the community. In the future, the method may be improved by the sequencing of only shorter segments of the gene, i.e., the most variable regions, to achieve sufficient discrimination of isolates. In Sweden, a country with a low prevalence of gonorrhea, this faster porB-based sequencing could be the method of choice for the precise and effective characterization of N. gonorrhoeae isolates.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the technical assistance of Angela Steen, Margareta Jurstrand, Annika Hellberg, and Kirsti Jalakas Pörnull in the serological characterization.

The present study was performed in the National Reference Laboratory for Pathogenic Neisseria, Department of Clinical Microbiology, Örebro University Hospital, Örebro, Sweden.

The present study was supported by grants from the Research Committee of Örebro County, the Örebro University Hospital Research Foundation, and the National Institute for Public Health of Sweden.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berglund, T., H. Fredlund, and J. Giesecke. 2001. Epidemiology of the reemergence of gonorrhea in Sweden. Sex. Transm. Dis. 28:111-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berglund, T., M. Unemo, P. Olcén, J. Giesecke, and H. Fredlund. 2002. One year of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates in Sweden: the prevalence study of antibiotic susceptibility shows relation to the geographic area of exposure. Int. J. STD AIDS 13:109-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunham, R. C., F. A. Plummer, and R. S. Stephens. 1993. Bacterial antigenic variation, host immune response, and pathogen-host coevolution. Infect. Immun. 61:2273-2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carbonetti, N. H., and P. F. Sparling. 1987. Molecular cloning and characterization of the structural gene for protein I, the major outer membrane protein of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:9084-9088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ceron, C., J. Dopazo, E. L. Zapata, J. M. Carazo, and O. Trelles. 1998. Parallel implementation of DNAml program on message-passing architectures. Parallel Comput. 24:701-716. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooke, S. J., K. Jolley, C. A. Ison, H. Young, and J. E. Heckels. 1998. Naturally occurring isolates of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, which display anomalous serovar properties, express PIA/PIB hybrid porins, deletions in PIB or novel PIA molecules. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 162:75-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooke, S. J., H. de la Paz, C. L. Poh, C. A. Ison, and J. E. Heckels. 1997. Variation within serovars of Neisseria gonorrhoeae detected by structural analysis of outer-membrane protein PIB and by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Microbiology 143:1415-1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Derrick, J. P., R. Urwin, J. Suker, I. M. Feavers, and M. C. J. Maiden. 1999. Structural and evolutionary inference from molecular variation in Neisseria porins. Infect. Immun. 67:2406-2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Felsenstein, J. 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39:783-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felsenstein, J. 1993. PHYLIP: phylogenetic inference package, version 3.52.c. University of Washington, Seattle.

- 11.Fudyk, T. C., I. W. Maclean, N. J. Simonsen, E. N. Njagi, J. Kimani, R. C. Brunham, and F. A. Plummer. 1999. Genetic diversity and mosaicism at the por locus of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Bacteriol. 181:5591-5599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gill, M. J. 1991. Serotyping Neisseria gonorrhoeae: a report of the Fourth International Workshop. Genitourin. Med. 67:53-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gotschlich, E. C., M. E. Seiff, M. S. Blake, and M. Koomey. 1987. Porin protein of Neisseria gonorrhoeae: cloning and gene structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:8135-8139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hobbs, M. M., T. M. Alcorn, R. H. Davis, W. Fischer, J. C. Thomas, I. Martin, C. Ison, P. F. Sparling, and M. S. Cohen. 1999. Molecular typing of Neisseria gonorrhoeae causing repeated infections: evolution of porin during passage within a community. J. Infect. Dis. 179:371-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ison, C. A., L. Whitaker, and A. Renton. 1992. Concordance of auxotype/serovar classes of Neisseria gonorrhoeae between sexual contacts. Epidemiol. Infect. 109:265-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knapp, J. S., M. R. Tam, R. C. Nowinski, K. K. Holmes, and E. G. Sandström. 1984. Serological classification of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with use of monoclonal antibodies to gonococcal outer membrane protein I. J. Infect. Dis. 150:44-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mee, B. J., H. Thomas, S. J. Cooke, P. R. Lambden, and J. E. Heckels. 1993. Structural comparison and epitope analysis of outer-membrane protein PIA from strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with differing serovar specificities. J. Gen. Microbiol. 139:2613-2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ng, L.-K., M. Carballo, and J.-A. R. Dillon. 1995. Differentiation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates requiring proline, citrulline, and uracil by plasmid content, serotyping, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1039-1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Rourke, M., C. A. Ison, A. M. Renton, and B. G. Spratt. 1995. Opa-typing: a high resolution tool for studying the epidemiology of gonorrhoea. Mol. Microbiol. 17:865-875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piot, P., and M. Q. Islam. 1994. Sexually transmitted diseases in the 1990s. Global epidemiology and challenges for control. Sex. Transm. Dis. 21(Suppl. 2):S7-S13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plummer, F. A., J. N. Simonsen, H. Chubb, L. Slaney, J. Kimata, M. Bosire, J. O. Ndinya-Achola, and E. N. Ngugi. 1989. Epidemiologic evidence for the development of serovar-specific immunity after gonococcal infection. J. Clin. Investig. 83:1472-1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poh, C. L., Q. C. Lau, and V. T. K. Chow. 1995. Differentiation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae IB-3 and IB-7 serovars by direct sequencing of protein IB gene and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Med. Microbiol. 43:201-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Posada, D., K. A. Crandall, M. Nguyen, J. C. Demma, and R. P. Viscidi. 2000. Population genetics of the porB gene of Neisseria gonorrhoeae: different dynamics in different homology groups. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17:423-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sandström, E., and D. Danielsson. 1980. Serology of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Classification by co-agglutination. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. Sect. B 88:27-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sandström, E., P. Lindell, B. Härfast, F. Blomberg, A.-C. Ryden, and S. Bygdeman. 1985. Evaluation of a new set of Neisseria gonorrhoeae serogroup W-specific monoclonal antibodies for serovar determination, p. 26-30. In G. K. Schoolnik (ed.), The pathogenic neisseriae. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 26.Spaargaren, J., J. Stoof, H. Fennema, R. Coutinho, and P. Savelkoul. 2001. Amplified fragment length polymorphism fingerprinting for identification of a core group of Neisseria gonorrhoeae transmitters in the population attending a clinic for treatment of sexually transmitted diseases in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2335-2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tam, M. R., T. M. Buchanan, E. G. Sandström, K. K. Holmes, J. S. Knapp, A. W. Siadak, and R. C. Nowinski. 1982. Serological classification of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with monoclonal antibodies. Infect. Immun. 36:1042-1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thompson, D. K., C. D. Deal, C. A. Ison, J. M. Zenilman, and M. C. Bash. 2000. A typing system for Neisseria gonorrhoeae based on biotinylated oligonucleotide probes to PIB gene variable regions. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1652-1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trees, D. L., A. J. Schultz, and J. S. Knapp. 2000. Use of the neisserial lipoprotein (Lip) for subtyping Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2914-2916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Unemo, M., T. Berglund, P. Olcén, and H. Fredlund. 2002. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis as an epidemiologic tool for Neisseria gonorrhoeae; identification of clusters within serovars. Sex. Transm. Dis. 29:25-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van de Peer, Y., and R. De Wachter. 1994. TREECON for Windows: a software package for the construction and drawing of evolutionary trees for the Microsoft Windows environment. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 10:569-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Ley, P., J. E. Heckels, M. Virji, P. Hoogerhout, and J. T. Poolman. 1991. Topology of outer membrane porins in pathogenic Neisseria spp. Infect. Immun. 59:2963-2971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Looveren, M., C. A. Ison, M. Ieven, P. Vandamme, I. M. Martin, K. Vermeulen, A. Renton, and H. Goossens. 1999. Evaluation of the discriminatory power of typing methods for Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2183-2188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Viscidi, R. P., J. C. Demma, J. Gu, and J. Zenilman. 2000. Comparison of sequencing of the por gene and typing of the opa gene for discrimination of Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains from sexual contacts. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:4430-4438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zak, K., J.-L. Diaz, D. Jackson, and J. E. Heckels. 1984. Antigenic variation during infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae: detection of antibodies to surface proteins in sera of patients with gonorrhea. J. Infect. Dis. 149:166-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]