Abstract

We describe a multiplex allele-specific (MAS)-PCR assay to detect simultaneously mutations in the first and third bases of the embB gene codon 306ATG. These mutations are known to confer ethambutol (EMB) resistance in the majority of clinical Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates worldwide. The mutated bases are revealed depending on the presence or absence of the respective indicative fragments amplified from the embB306 wild-type allele. Initially optimized on purified DNA samples, the assay was tested on crude cell lysates and auramine-stained sputum slide DNA preparations with the same reproducibility and interpretability of the generated profiles in agarose gel electrophoresis. Since EMB resistance is generally linked to multiple-drug resistance (MDR), the MAS-PCR assay for EMB resistance detection can be used in clinical laboratory practice in areas with a high prevalence and a high transmission rate of MDR-EMB-resistant tuberculosis.

Ethambutol (EMB) [dextro-2,2′-(ethylenediimino)di-1-butanol] is a first-line drug used for antitubercular therapy in combination with other drugs as recommended by the World Health Organization DOTS/DOTS-Plus regimens, as well as by the standard treatment protocol officially adopted by the Russian Ministry of Health. The EMB action on tubercle bacilli is bactericidal and is due to its interactions as an arabinose analogue with the target arabinosyl transferase (1, 9). As a result, the synthesis of sugars (arabinan and, consequently, arabinogalactan and lipoarabinomannan), necessary for cell wall construction, is prevented. Finally, the accumulation of mycolic acids results in cell death. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis emb operon encoding different arabinosyl transferases includes three contiguous genes, namely, embC, embA, and embB that exhibit 65% similarity to each other (9). Analysis of EMBr clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis identified several mutations in these genes conferring EMB resistance, mostly in embB, and up to 90% of them were found in codon 306ATG-Met (5, 8). Five different mutations were uncovered in this codon (ATG → GTG/CTG/ATA, ATC, and ATT), resulting in three different amino acid shifts (Met → Val, Leu, or Ile) (8). EmbB Met306 is located in a cytoplasmatic loop that forms an EMB resistance-determining region (9), and embB mutations undoubtedly mediate EMB resistance rather than act simply as surrogate markers of resistance (5). About 30% of EMBr strains had no embB mutations (5), and a recently undertaken extensive study suggested more genes are involved in EMB resistance in some strains (4). However, about one-fourth of EMBr strains still lacked any known mutation inferred to participate in EMB resistance, implying multiple molecular pathways to the EMB resistance phenotype, and some of them remain to be discovered.

The prevalence of resistance to EMB, initial and acquired, is not generally high and varies in different countries from 1.3% in Canada (6) to 23.3% in Pakistan (3), with an overall average of 4 to 9% (for more information about initial resistance, see references 2, 5, 14, and 15), and is predominant among patients with multidrug-resistant (MDR) tuberculosis (TB). On the other hand, EMB monoresistance is extremely rare (9). Since EMB resistance does not occur frequently, EMB is a valuable drug for antitubercular therapy. However, the possibility of EMB resistance development, even if generally not very high, necessitates its rapid detection, which may be achieved by using molecular techniques. So far, elaborate and expensive methods such as sequencing (2, 8) have mostly been used in embB mutational studies. Other authors have suggested PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) (7) and dot blot hybridization (11) assays based on PCR, followed by either restriction endonuclease analysis or DNA hybridization, respectively.

Given this situation, we sought to develop a simple and rapid assay based exclusively on embB306 PCR for the detection of EMB resistance in M. tuberculosis clinical isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and susceptibility testing.

Thirty-four M. tuberculosis isolates were recovered from 34 unrelated adult patients (15 to 63 years old) with newly diagnosed or recurrent pulmonary TB. These patients were from St. Petersburg and neighboring provinces of northwestern Russia and were admitted to the hospital of St. Petersburg Institute of Phthisiopulmonology between 1999 and 2001. Löwenstein-Jensen medium was used for the M. tuberculosis culture. Susceptibility testing to rifampin (RIF), isoniazid (INH), pyrazinamide, streptomycin (STR), and EMB was done by the method of absolute concentration as recommended by the Russian Ministry of Health (order no. 558 of 28 June 1978) and described in detail previously (12).

DNA preparation.

DNA used for the PCR analysis was either extracted from cultured cells and purified as described earlier (10) or obtained by resuspending a mycobacterial colony in 200 μl of 1× TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl-1 mM EDTA [pH 7.4] with or without Chelex 100 [Sigma] at 5% [wt/vol]), followed by boiling for 30 min. After centrifugation, the DNA containing supernatant (cell lysate) was harvested and stored at 4°C until used.

The DNA samples from the auramine-stained sputum smears (1+, 2+, or 3+ cell count [13]) were obtained by scraping the material from the glass slide into a sterile Eppendorf tube and then resuspending it in a total volume of 75 μl of extraction buffer (15% Chelex 100 [Sigma], 0.5% Nonidet P-40 [Sigma], 0.5% Tween 20), followed by incubation for 20 min in a boiling water bath. After centrifugation, the removed supernatant was used for PCR.

PCR.

A multiplex allele-specific (MAS)-PCR assay was designed to detect simultaneously mutations in the embB306 first and third bases, which are known to confer EMB resistance (8). The inner primers were selected to stop at the first and third bases of the codon 306 wild-type allele ATG (Fig. 1). Any mismatch at the 3′ end of the inner primer would result, under appropriate stringent PCR conditions, in the absence of a respective amplified product. Thus, a strain with the embB306 wild-type allele would produce two allele-specific bands of 160 and 210 bp (Fig. 2, lanes 1 and 5), a strain with embB306 mutated in the first base would produce a 210-bp fragment only (Fig. 2, lanes 3, 4, and 6), and a strain with embB306 mutated in the third base would produce only a 160-bp fragment (Fig. 2, lanes 2 and 7). In addition, a 324-bp fragment is invariably amplified by the outer primers Emb1F and Emb2R (Fig. 2). The following primers were used for a single-tube PCR targeting a portion of the embB gene (embB positions 730 to 1053 in strain H37Rv; accession number Z80343, positions 33265 to 33588): two outer primers (forward Emb1F [5′-GGGCGGGGCTCAATTGCC] and reverse Emb2R [5′-GCGCATCCACAGACTGGCGTC]) and two inner primers (forward Emb306A [5′-GACGACGGCTACATCCTGGGCA] and reverse Emb306B [5′-GGTCGGCGACTCGGGCC]). Purified DNA sample (0.1 μl) or 10 μl of a lysate or sputum slide preparation was added to the PCR mixture (final volume, 30 μl) that contained 5 pmol of the Emb2R and Emb306A primers, 50 pmol of the Emb1F and Emb306B primers, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 U of recombinant Taq DNA polymerase (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), and 200 μM concentrations of each of the deoxynucleoside triphosphates. The reaction was performed in a PTC-100 thermal controller (MJ Research, Inc.) as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 4 min; followed by 6 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 75°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 20 s; followed by 6 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 74°C for 40 s, and 72°C for 20 s; followed by 20 cycles (or 25 cycles for sputum slides or lysate probes) of 94°C for 1 min, 73°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 20 s; with a final elongation at 72°C for 2 min. The amplified fragments were electrophoresed in 1.5% standard agarose (Quantum Bioprobe) gels and visualized under UV light.

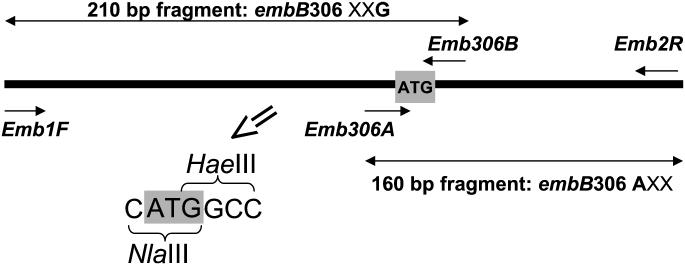

FIG. 1.

Schematic view of the embB gene fragment targeted by the MAS-PCR assay. Short arrows indicate the primers, long double-sided arrows indicate the allele-specific PCR fragments amplified in the absence of respective mutation. An X represents any base (A, T, C, or G). The embB codon 306 ATG is in boldface and in a shaded box. NlaIII and HaeIII restriction enzymes' sites related to embB306 ATG are shown in the enlarged image.

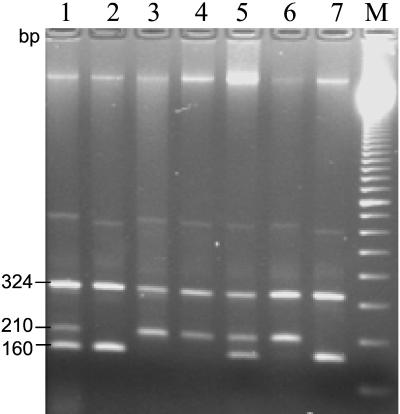

FIG. 2.

MAS-PCR profiles of EMBr M. tuberculosis clinical strains. Lanes: 1 and 5, strains with embB306 wild-type allele; 2 and 7, strains with the embB306 ATG→ATH mutation; 3, 4, and 6, strains with embB306 ATG→BTG mutation (“B” represents G, C, or T; “H” represents A, C, or T). Lane M, 100-bp DNA ladder (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

PCR-RFLP analysis.

A primer pair EmbF (5′-ATTCGGCTTCCTGCTCTGG) and EmbR (5′-GAACCAGCGGAAATAGTTGG) was used to amplify a shorter embB fragment-spanning codon 306 (embB positions 852 to 969 in strain H37Rv [accession number Z80343, positions 33387 to 33504]) under the following PCR conditions: initial denaturation at 95°C for 4 min; followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 60°C for 40 s, and 72°C for 20 s; with a final elongation step at 72°C for 2 min. The amplified 118-bp fragment was subjected to cleavage by NlaIII (New England Biolabs) and HaeIII (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) restriction endonucleases, and the digests obtained were separated in 3% MetaPhor agarose gels (FMC BioProducts).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The 34 M. tuberculosis strains studied included 10 EMBs strains and all available EMBr strains (i.e., 24 strains) isolated in the St. Petersburg area of the Russian Federation from 1999 to 2001. The EMBs strains were pansusceptible, and the EMBr strains were MDR. All 24 MDR strains were EMBr; 22 of these strains were also resistant to STR, RIF, and INH, 1 strain was resistant to STR and INH, and 1 strain was resistant to STR and RIF.

The MAS-PCR assay was used to detect mutations in the embB codon 306 (Fig. 1 and 2). All 10 EMBs strains showed a three-band profile, as expected, implying no mutation in embB306 (e.g., see Fig. 2, lanes 1 and 5). For all 24 EMBr strains, the following distribution of wild-type and mutated alleles was observed: ATG (wild type) 11 strains; BTG, 9 strains; and ATH, 4 strains (according to the degenerated base code, “B” represents G, C, or T and “H” represents A, C, or T). Based on the reported distribution of embB306 mutations (4, 5, 11), we consider ATH most likely to be the ATA allele (Ile) and BTG to be the GTG (Val) or CTG (Leu) allele. Of note, the assay design provides double PCR quality confirmation so as to rule out false-negative results due to a lack of amplification. The amplifiability of the entire target gene fragment is proven, first, by obligatory amplification of at least one of two allele-specific fragments (160 or 210 bp) and, second, by generation of the invariant 324-bp PCR product spanning the entire embB306 region under study (Fig. 2).

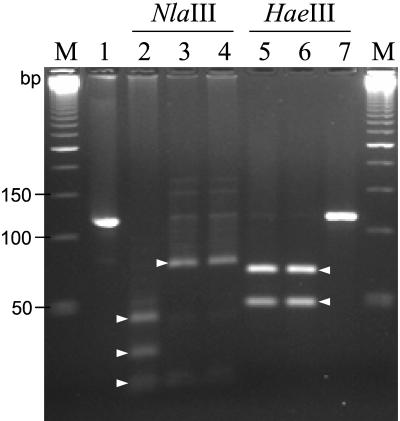

In order to verify the results generated by the MAS-PCR assay, a shorter portion (118 bp) of the embB gene was amplified and cleaved with the NlaIII and HaeIII restriction endonucleases. The short embB306 sequence under study and the recognition sites of the enzymes are shown in Fig. 1. The NlaIII recognition sequence (CATG↑) occurs in three places in the 118-bp PCR fragment of a wild-type strain; this cleavage results in four digests of 21, 23, 30, and 44 bp (Fig. 3, lane 2). Any mutation in embB306 changes one NlaIII site and results in three digests of 21, 23, and 74 bp (Fig. 3, lanes 3 and 4). A single recognition site of HaeIII (GG↑CC) in the embB fragment under study is associated with codon 306ATG (Fig. 1). This HaeIII site can be altered only if a mutation occurs in the embB306 third base (G). In such a mutant allele (ATG 224 ATH) the PCR fragment will remain uncut by HaeIII (118 bp; Fig. 3, lane 7), whereas a two-band profile (50 and 68 bp) will be observed in embB306 wild-type or differently mutated strains (Fig. 3, lanes 5 and 6). To summarize, NlaIII distinguishes between the wild type and any mutant allele (Fig. 3, lane 2 versus lanes 3 and 4), whereas HaeIII permits further discrimination of the mutants depending on the base mutated (first/A or third/G; Fig. 3, lane 6 versus lane 7). Thus, for all of the strains studied, the resulting PCR-RFLP data corroborated those generated by the MAS-PCR assay.

FIG. 3.

PCR-RFLP analysis of the amplified 118-bp embB306 fragment of M. tuberculosis strains with NlaIII and HaeIII. Lanes: 2 to 4, NlaIII-RFLP profiles; 5 to 7, HaeIII-RFLP profiles; 1, undigested PCR product (118 bp), 2 and 5, strains with embB306 wild-type allele (ATG); 3 and 6, strains with embB codon 306 mutated in the first base (ATG→BTG); 4 and 7, strains with embB codon 306 mutated in the third base (ATG→ATH). Lane M, 50-bp DNA ladder (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Short triangular arrows indicate specific digests produced by NlaIII (21/23, 30, and 44 bp in lane 2; 21/23 and 74 bp in lanes 3 and 4) and HaeIII (50 and 68 bp in lanes 5 and 6). The 21- and 23-bp fragments present one weak band.

The assay was originally performed on purified DNA samples with which the PCR conditions and concentrations were optimized. It was then tested on cell lysates and sputum slide preparations, all from the same patients. The MAS-PCR profiles obtained were found to be as reproducible and interpretable for both cell lysates and slide DNA preparations as for purified DNA samples.

To conclude, although the described assay does not identify the particular shifts in embB codon 306, it does disclose the presence of any of the five described embB306 mutations. Generally, notwithstanding a multiplicity of molecular mechanisms, EMB resistance results from embB306 alterations in up to 60% of M. tuberculosis clinical strains worldwide (5). For this reason, the MAS-PCR assay can be suggested as a simple and rapid tool for detecting EMB resistance mediated by embB306 mutations in clinical M. tuberculosis strains with reasonably high probability. It is applicable also for direct detection from stained sputum slide DNA preparations. The assay is easy to perform since it is based on a single-tube PCR-minigel electrophoresis without any further extension and can be implemented in a clinical laboratory setting in countries with a high prevalence and a high transmission rate of MDR TB.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lidia Steklova for providing us with some of the clinical isolates. We also thank Marie-Françoise Saron and Alessandra Riva for critical reading of the manuscript and for English language corrections.

This study was partly supported by the Réseau International des Instituts Pasteur et Instituts Associés, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alcaide, F., G. E. Pfyffer, and A. Telenti. 1997. Role of embB in natural and acquired resistance to ethambutol in mycobacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2270-2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Escalante, P., S. Ramaswamy, H. Sanabria, H. Soini, X. Pan, O. Valiente-Castillo, and J. M. Musser. 1998. Genotypic characterization of drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Peru. Tuber. Lung Dis. 79:111-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karamat, K. A., S. Rafi, and S. A. Abbasi. 1999. Drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a four-year experience. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 49:262-265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramaswamy, S. V., A. G. Amin, S. Goksel, C. E. Stager, S.-J. Dou, H. El Sahli, S. L. Moghazeh, B. N. Kreiswirth, and J. M. Musser. 2000. Molecular genetic analysis of nucleotide polymorphisms associated with ethambutol resistance in human isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:326-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramaswami, S. V., and J. M. Musser. 1998. Molecular genetic basis of antimicrobial agent resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: 1998 update. Tuber. Lung Dis. 79:3-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Remis, R. S., F. Jamieson, P. Chedore, A. Haddad, and L. Vernich. 2000. Increasing drug resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in Ontario, Canada, 1987-1998. Clin. Infect. Dis. 31:427-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rinder, H., K. T. Mieskes, and T. Loscher. 2001. Heteroresistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung. Dis. 5:339-345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sreevatsan, S., K. E. Stockbauer, X. Pan, B. N. Kreiswirth, S. L. Moghazeh, W. R. Jacobs, Jr., A. Telenti, and J. M. Musser. 1997. Ethambutol resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: critical role of embB mutations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1677-1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Telenti, A., W. J. Philipp, S. Sreevatsan, C. Bernasconi, K. E. Stockbauer, B. Wieles, J. M. Musser, and W. R. Jacobs, Jr. 1997. The emb operon, a gene cluster of Mycobacterium tuberculosis involved in resistance to ethambutol. Nat. Med. 3:567-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Embden, J. D. A., M. D. Cave, J. T. Crawford, J. W. Dale, K. D. Eisenach, B. Gicquel, P. Hermans, C. Martin, R. McAdam, T. M. Shinnik, et al. 1993. Strain identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by DNA fingerprinting: recommendations for a standardized methodology. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:406-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Victor, T. C., A. M. Jordaan, A. van Rie, G. D. van der Spuy, M. Richardson, P. D. van Helden, and R. Warren. 1999. Detection of mutations in drug resistance genes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by a dot blot hybridization strategy. Tuber. Lung Dis. 79:343-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Viljanen, M. K., B. I. Vyshnevskiy, T. F. Otten, E. Vyshnevskaya, M. Marijamaki, H. Soini, P. J. Laippala, and A. V. Vasilyef. 1998. Survey of drug-resistant tuberculosis in northwestern Russia from 1984 through 1994. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 17:177-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. 1998. Laboratory services in tuberculosis control. Part II. Microscopy, p. 43. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 14.Yang, Z. H., A. Rendon, A. Flores, R. Medina, K. Ijaz, J. Llaka, K. D. Eisenach, J. H. Bates, A. Villarreal, and M. D. Cave. 2001. A clinic-based molecular epidemiologic study of tuberculosis in Monterrey, Mexico. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 5:313-320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshiyama, T., S. Supawitkul, N. Kunyanone, D. Riengthong, H. Yanai, C. Abe, N. Ishikawa, P. Akarasewi, V. Payanandana, and T. Mori. 2001. Prevalence of drug-resistant tuberculosis in an HIV endemic area in northern Thailand. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 5:32-39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]