Abstract

Supplemental assays, such as recombinant immunoblot assays (RIBA), are used to confirm detection of antibodies to hepatitis C virus (HCV). However, due to their expense, they are not widely used in developing countries. The purpose of our study was to compare the results of second- and third-generation (G2 and G3, respectively) enzyme immunoassays (EIAs) and to resolve discordant results by using a supplemental assay to assess the reliability of G2 and G3 EIAs to confirm anti-HCV antibody-positive results. We performed both G2 and G3 EIAs for anti-HCV antibodies on 1,134 serum samples collected during the 2nd year of a longitudinal community-based study in Egypt; 35 samples with discordant results were tested by Abbott Laboratories Micro-Particle Immunoassay (M-EIA) and RIBA. Viremia was determined with an in-house nested reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) to detect HCV RNA. Concordance between the two assays (G2/G3) was 96.9%; 87 (7.7%) samples were positive and 1,012 (89.2%) were negative by both assays. For 17 samples, the discordant results were G2 assay negative and G3 assay positive, and for 18 samples, the discordant results were G2 assay positive and G3 assay negative. Among the 17 G2 assay-negative and G3 assay-positive samples, 15 were M-EIA positive and 7 were PCR positive. Among the 18 G2 assay-positive and G3 assay-negative samples, 2 were M-EIA positive and none were PCR positive. RIBA results from 24 discordant samples showed 87.5% agreement with the G3 EIA, 12.5% agreement with the G2 EIA, and 95.8% agreement with M-EIA. Eleven samples were indeterminate by RIBA and excluded from this analysis. Based on RIBA results, the sensitivity of the G3 EIA was 99%, compared to 89.8% for the G2 EIA, while the specificity of the G3 EIA was 99.8%, compared to 98.9% for the G2 EIA. These results show that the reliability of the G3 EIA in screening these sera is excellent, and the G3 assay can be used in the absence of supplemental tests where resources are limited. RIBA appears not to have advantages over the less expensive M-EIA screening assay. The main disadvantage of RIBA is the occurrence of indeterminate results, especially among problematic samples. Samples giving discordant results in multiple assays are often indeterminate with the RIBA.

Exposure to hepatitis C virus (HCV) is determined by testing for anti-HCV antibodies, while active infection is marked by the presence of HCV RNA by using reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR). The first enzyme immunoassay (EIA) for the detection of anti-HCV antibodies, developed 12 years ago by using a recombinant HCV C100-3 peptide (9), had relatively poor specificity and sensitivity (2, 4). Seroconversion in patients with acute HCV infection is often not detected until 3 months or longer after infection (16). The second-generation (G2) assay, introduced in 1991, incorporated recombinant antigens from nonstructural regions (NS3 and NS4) together with an antigen from the core region of HCV (2, 12). The G2 EIA was superior to the G1 EIA in both sensitivity and specificity, and its use in blood banks has dramatically reduced the incidence of posttransfusion hepatitis (8). The G3 EIA, which added an NS5 epitope, should increase the reliability of the test and increase detection of anti-HCV earlier in the course of infection (5, 6).

Supplemental tests, based on either neutralization or recombinant immunoblot assays (RIBA), possess high specificity and are useful in identifying false-positive test results (15), but are expensive. Because of their relatively low sensitivity, they are not recommended for screening for anti-HCV antibodies (7). In developing countries, supplemental tests are often omitted because of their expense, and the reliability of the anti-HCV EIAs without supplemental tests becomes very important (13). The objective of this study was to compare the sensitivity and specificity of G2 and G3 EIAs for detection of anti-HCV antibodies by using sera from Egyptian subjects, in whom genotype 4 accounts for 90% of infection (14). In addition, the advantages of using RIBA as a supplemental test were assessed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

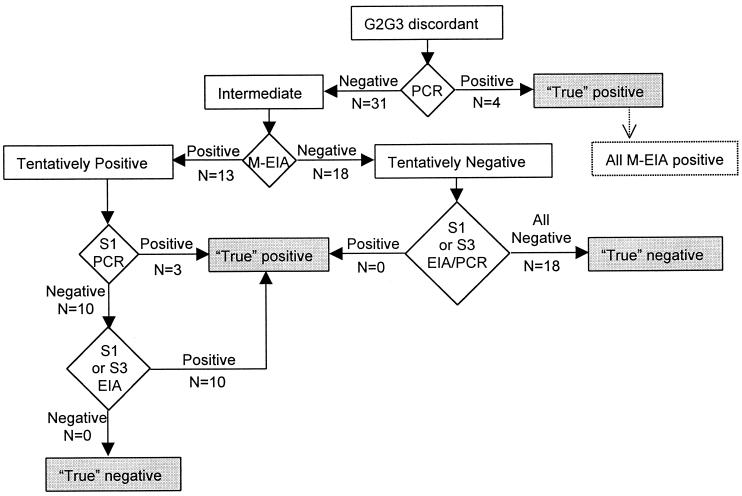

We tested 1,134 serum samples collected during the 2nd year of a longitudinal community-based study in Assiut Governorate, Egypt (11), with both G2 and G3 EIAs from Abbott Laboratories (Wiesbaden, Delknheim, Germany) following the manufacturer's instructions and compared the tests' results. To further evaluate discordant G2/G3 assay results, we defined samples as truly positive or negative based on an algorithm representing the following elements (Fig. 1): (i) an in-house RT-PCR generated from the 5′-untranslated region of the HCV genome (1) performed with the same sample and additional samples from the same individual in the prior or subsequent years, (ii) G3 results from prior or subsequent years, and (iii) Micro-Particle Immunoassay (M-EIA; Abbott Laboratories) results for the discordant samples. The sensitivity and specificity of the G2 and G3 assays were initially calculated by assuming true serostatus according to the algorithm. To further support the assessment of sensitivity and specificity of the G2 and G3 assays, discordant samples were subsequently tested with the G3 RIBA (Chiron, Emeryville, Calif.). The sensitivity and specificity of the G2 and G3 assays were once again calculated on the basis of the RIBA, and the two methods of assessing sensitivity and specificity were compared. For all calculations of sensitivity and specificity, the samples with concordant G2/G3 assay results were included with the assumption that those results represented true positives and true negatives.

FIG. 1.

Algorithm to assign serostatus (shaded boxes) of discordant samples on the basis of PCR, M-EIA, and testing of additional samples from the same individuals. S1, serum sample from the year before discordant samples; S3, serum sample from the year following discordant samples.

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Maryland and the Egyptian Ministry of Health and Population.

RESULTS

Eighty-seven (7.7%) of the serum samples were positive by both the G2 and G3 EIAs, while 1,012 (89.2%) were negative by both tests, with a resultant concordance of 96.9% (Table 1). Among the 35 discordant G2/G3 EIA results, there were 17 specimens G2 assay negative and G3 assay positive, while 18 specimens were G2 assay positive and G3 assay negative. Results of M-EIA testing of the 35 discordant samples were more frequently in agreement with the G3 EIA result (concordance of 88.6% [31 of 35]) than with the G2 EIA result (11.4% [4 of 35]). Among the 18 samples with G2 assay-positive and G3 assay-negative results, 2 were M-EIA positive, while 15 of the 17 sera that were G3 assay positive and G2 assay negative were M-EIA positive (Table 2). The results of HCV RNA testing of the discordant samples also showed better agreement with the G3 EIA results. All 18 samples that tested positive by the G2 EIA, but negative by the G3 EIA, were negative by RT-PCR. However, 7 (41.2%) of the 17 individuals with G3 assay-positive and G2 assay-negative results had detectable HCV RNA in the same sample or in a sample from the same individual taken a year earlier.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of G2 and G3 EIA results for anti-HCV antibodies

| G2 EIA result | No. (%) with G3 EIA result

|

Total no. of samples | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | ||

| Negative | 1,012 (89.2) | 17 (1.5) | 1,030 |

| Positive | 18 (1.6) | 87 (7.7) | 104 |

| Total | 1,029 | 105 | 1,134 |

TABLE 2.

Comparison of G2/G3 discordant pairs and M-EIA results

| EIA result | No. (%) with M-EIA result

|

Total no. of samples | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G2 | G3 | Negative | Positive | |

| Positive | Negative | 16 (88.9) | 2 (11.1) | 18 |

| Negative | Positive | 2 (11.8) | 15 (88.2) | 17 |

| Total | 18 | 17 | 35 | |

Among the 35 discordant samples, RIBA was positive in 11 samples, negative in 13, and indeterminate in 11 (Table 3). G3 EIA results agreed with 87.5% (21 of 24) of interpretable RIBA results. Ten samples were positive by both RIBA and G3 EIA, and 11 were negative by both. Two samples were negative by RIBA, but positive by G3 EIA, while one sample was positive by RIBA and negative by G3 EIA. However, G2 EIA and RIBA results were concordant in only 3 of 24 (12.5%) samples. Excluding the 11 samples with indeterminate RIBA results, there was only one discordant result between RIBA and M-EIA (Table 4). This sample was positive by M-EIA and G3 EIA, but negative by RIBA. All samples with indeterminate RIBA results were PCR negative.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of G2/G3 discordant pairs and RIBA results

| EIA result | No. with RIBA result

|

Total no. of samples | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G2 | G3 | Negative | Intermediate | Positive | |

| Positive | Negative | 11 | 6 | 1 | 18 |

| Negative | Positive | 2 | 5 | 10 | 17 |

| Total | 13 | 11 | 11 | 35 | |

TABLE 4.

Comparison of RIBA and M-EIA results

| M-EIA result | No. with RIBA resulta

|

Total no. of samples | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Intermediate | Positive | ||

| Negative | 12 | 6 | 0 | 18 |

| Positive | 1 | 5 | 11 | 17 |

| Total | 13 | 11 | 11 | 35 |

Concordance = 96% (excluding those intermediate by RIBA).

Based on the algorithm (Fig. 1) used to define “true” positive and negative serostatus, the sensitivity of the G3 EIA was 98.1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 92.6 to 99.7), compared to 85.6% (95% CI, 77.0 to 91.5) for the G2 EIA, while the specificity of the G3 EIA was 99.8% (95% CI, 99.2 to 99.9), compared to 98.4% (95% CI, 97.4 to 99.0) for the G2 EIA. The assessment on the basis of the RIBA, excluding samples with indeterminate RIBA results, was similar: the sensitivity of the G3 EIA was 99.0% (95% CI, 93.7 to 99.9), compared to 89.8% (95% CI, 81.6 to 94.7) for the G2 EIA, while the specificity of the G3 EIA was 99.8% (95% CI, 99.2 to 99.9), compared to 98.9% (95% CI, 98.0 to 99.4) for the G2 EIA.

DISCUSSION

This investigation with sera from over 1,100 subjects collected during a cross-sectional serosurvey in Egypt shows that the sensitivity and specificity of the G3 EIA are outstanding, a finding consistent with a recent review of predominantly small studies (6).

The G3 EIA clearly demonstrated sensitivity and specificity superior to those of the G2 EIA. For the subset of problematic, discordant samples, the M-EIA agreed with the G3 assay eight times as frequently as it did with the G2 assay.

The excellent agreement between the results of the G3 EIA and M-EIA is not surprising, since both include the NS5 epitope, which is not included in the G2 assay. Because of its lower sensitivity, surveillance data based on G2 EIA testing may result in a spuriously low prevalence of anti-HCV antibodies, especially in populations with relatively high prevalence of infection, in which false-positives are less of a concern.

The concordance between RIBA and M-EIA was almost complete for the samples with definitive RIBA results. RIBA results did not prove more helpful than M-EIA, because the calculations of G2 and G3 EIA reliability were not substantially changed when comparisons were made with RIBA results. Furthermore, one-third of the RIBA tests had indeterminate results, greatly limiting its usefulness for confirmation of EIA results, consistent with previous assessments (13).

In developing countries, where resources are scarce, use of supplemental tests (e.g., RIBA) is generally not fiscally possible. In this context, G3 EIA results appear sufficiently reliable for detecting exposure to HCV without supplemental assays. The decision to use these supplemental tests for clinical situations in developed countries, where resources are more readily available, must be based on the individual situation. It has been suggested that supplemental tests be used only in populations with expected low prevalence, such as blood banks (3, 10). RIBA appears to have no advantage over the less expensive M-EIA in supporting positive screening test results, and the crucial clinical information needed to determine who has chronic infection is provided by RT-PCR.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ismail Sallam, as well as Wagida Anwar, Magda Rakha, Said Ohn, and other members of the Egyptian Ministry of Health and Population for their support and encouragement of this research. We also thank Robert Purcell of the National Institutes of Health for advice and Mohamed Nafeh and Ahmed Medhat and the field team from the Department of Tropical Medicine at Assiut University, who collected blood samples used in this study. This investigation could not have been performed without the careful project management in Egypt of Mar-Jan Ostrowski.

This study was supported by USAID grant no. 263-G-00-96-00043-00 and Wellcome Trust grant no. 059113/Z/99/Z.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdel-Hamid, M., D. C. Edelman, W. E. Highsmith, and N. T. Constantine. 1997. Optimization, assessment, and proposed use of a direct nested reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction protocol for the detection of hepatitis C virus. J. Hum. Virol. 1:58-65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alter, H. J. 1992. New kit on the block: evaluation of second-generation assays for detection of antibody to the hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 15:350-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anonymous. 1999. EASL International Consensus. Conference on Hepatitis C. Paris, 26-27 February 1999. Consensus statement. J. Hepatol. 31(Suppl. 1):3-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baath, L., A. Widell, and E. Nordenfelt. 1992. A comparison between one first generation and three second generation anti-HCV ELISAs: an investigation in high- and low-risk subjects in correlation with recombinant immunoblot assay and polymerase chain reaction. J. Virol. Methods 40:287-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bansal, J., N. T. Constantine, X. Zhang, J. D. Callahan, V. C. Marsiglia, and K. C. Hyams. 1993. Evaluation of five hepatitis C virus screening tests and two supplemental assays: performance when testing sera from sexually transmitted diseases clinic attendees in the USA. Clin. Diagn. Virol. 1:113-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colin, C., D. Lanoir, S. Touzet, L. Meyaud-Kraemer, F. Bailly, and C. Trepo. 2001. Sensitivity and specificity of third-generation hepatitis C virus antibody detection assays: an analysis of the literature. J. Viral Hepat. 8:87-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Constantine, N. T., J. D. Callahan, J. Bansal, X. Zhang, and K. C. Hymas. 1992. Concordance of tests to detect antibodies to hepatitis C virus. Lab. Med. 23:807-810. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dow, B. C., E. A. Follett, T. Jordan, F. McOmish, J. Davidson, J. Gillon, P. L. Yap, and P. Simmonds. 1994. Testing of blood donations for hepatitis C virus. Lancet 343:477-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuo, G., Q. L. Choo, H. J. Alter, G. L. Gitnick, A. G. Redeker, R. H. Purcell, T. Miyamura, J. L. Dienstag, M. J. Alter, C. E. Stevens, et al. 1989. An assay for circulating antibodies to a major etiologic virus of human non-A, non-B hepatitis. Science 244:362-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lauer, G. M., and B. D. Walker. 2001. Hepatitis C virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 345:41-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nafeh, M. A., A. Medhat, M. Shehata, N. N. Mikhail, Y. Swifee, M. Abdel-Hamid, S. Watts, A. D. Fix, G. T. Strickland, W. Anwar, and I. Sallam. 2000. Hepatitis C in a community in Upper Egypt. 1. Cross-sectional survey. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 63:236-241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakagiri, I., K. Ichihara, K. Ohmoto, M. Hirokawa, and N. Matsuda. 1993. Analysis of discordant test results among five second-generation assays for anti-hepatitis C virus antibodies also tested by polymerase chain reaction-RNA assay and other laboratory and clinical tests for hepatitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:2974-2980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pawlotsky, J. M., I. Lonjon, C. Hezode, B. Raynard, F. Darthuy, J. Remire, C. J. Soussy, and D. Dhumeaux. 1998. What strategy should be used for diagnosis of hepatitis C virus infection in clinical laboratories? Hepatology 27:1700-1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ray, S. C., R. R. Arthur, A. Carella, J. Bukh, and D. L. Thomas. 2000. Genetic epidemiology of hepatitis C virus throughout Egypt. J. Infect. Dis 182:698-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schroter, M., P. Schafer, B. Zollner, S. Polywka, R. Laufs, and H. H. Feucht. 2001. Strategies for reliable diagnosis of hepatitis C infection: the need for a serological confirmatory assay. J. Med. Virol. 64:320-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Poel, C. L., H. T. Cuypers, and H. W. Reesink. 1994. Hepatitis C virus six years on. Lancet 344:1475-1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]