Abstract

Embryonic stem (ES) cell technology allows modification of the mouse germline from large deletions and insertions to single nucleotide substitutions by homologous recombination. Identification of these rare events demands an accurate and fast detection method. Current methods for detection rely on Southern blotting and/or conventional PCR. Both the techniques have major drawbacks, Southern blotting is time-consuming and PCR can generate false positives. As an alternative, we here demonstrate a novel approach of Multiplex Ligation-dependent Probe Amplification (MLPA) as a quick, quantitative and reliable method for the detection of homologous, non-homologous and incomplete recombination events in ES cell clones. We have adapted MLPA to detect homologous recombinants in ES cell clones targeted with two different constructs: one introduces a single nucleotide change in the PCNA gene and the other allows for a conditional inactivation of the wild-type PCNA allele. By using MLPA probes consisting of three oligonucleotides we were able to simultaneously detect and quantify both wild-type and mutant alleles.

INTRODUCTION

Over the last two decades the use of mice to model human disease and discover gene function has greatly increased. This increase coincided with the ability to modify the mouse genome, from large deletions and insertions to subtle changes, such as single nucleotide exchanges. One of the most widely used methods to modify the mouse genome is gene targeting in embryonic stem (ES) cells. This method makes use of a targeting construct, containing the mutation, a selectable marker gene and large regions that are homologous to the gene to be modified (1). In general the construct is delivered to the ES cells by electroporation and eventually integrates in the genome through homologous recombination, although non-homologous integration is observed more frequently. Recently, oligonucleotide targeting has been described as an alternative to conventional gene targeting (2).

Homologous recombination events can be detected by methods such as Southern blotting and PCR. However, these methods have several drawbacks. Southern blot analysis is time-consuming, and unique external probes can be difficult to make (e.g. repetitive DNA sequences). PCR based methods are much faster. However, with the use of conventional targeting constructs, the homology arm may be too long to be amplified by PCR. In addition, PCR may generate false positives when introducing single nucleotide exchanges by oligonucleotide targeting. To overcome all these drawbacks, an alternative method that is sensitive, robust, quantitative and high throughput is desired.

The Multiplex Ligation-dependent Probe Amplification (MLPA) (3) is a new and fast method designed for simultaneous quantification of copy numbers of several dozens of specific genomic sequences. MLPA is easy to perform, requires only 20 ng of sample DNA and can discriminate sequences that differ in only a single nucleotide. It can also be used for relative quantification of mRNAs (4) and to determine the methylation status of CpG islands surrounding promoter regions (5). MLPA has a very interesting potential for basic, translational and clinical research. So far MLPA is mainly used for diagnostical purposes, such as detecting copy number changes of human genomic DNA sequences using DNA samples derived from blood (6), amniotic fluid (7) or tumors (8).

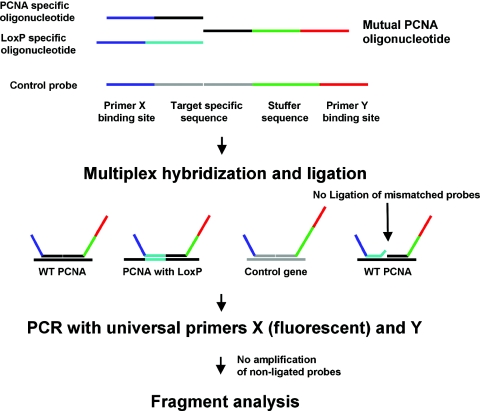

In MLPA, up to 45 probes, each consisting of two oligonucleotides that hybridize immediately adjacent to each other on the target DNA are added in one reaction (Figure 1). Besides a target-specific sequence, each of these two oligonucleotides contains one of the two sequences recognized by a universal PCR primer pair. After denaturing the sample DNA, the MLPA probes are added and allowed to hybridize overnight. The two parts of each MLPA probe are then ligated to each other by a specific ligase enzyme, on condition that both perfectly hybridize to their specific target sequence. Ligated probes are exponentially PCR amplified using a universal primer pair. Non-hybridized probes are not removed enabling a high throughput ‘one-tube’ method. MLPA probes are designed such that each amplification product is identified by size and after separation by capillary electrophoresis can be quantified. Changes in relative probe signals between samples reflect changes in copy number of the probe target sequences.

Figure 1.

Principle of adapted MLPA. For the targeted PCNA gene, two MLPA probes specific for either the 5′ or 3′ LoxP sequence were designed, each consisting of three oligonucleotides: one synthetic mutual PCNA specific 5′ phosphorylated oligonucleotide, one synthetic PCNA specific and one synthetic LoxP specific oligonucleotide. The short synthetic oligonucleotides consist of a 5′ universal primer sequence X, a short stuffer sequence and a target-specific 3′ sequence. The mutual PCNA specific oligonucleotide consists of a 5′ target-specific sequence designed to hybridize in juxtaposition to the synthetic oligonucleotides and a 3′ universal primer sequence Y. In addition, for copy number quantification 12 ordinary MLPA probes consisting of two oligonucleotides, one short synthetic and one longer phage M13 derived (with different stuffer lengths), each specific for different genes in the mouse genome. After denaturing the sample DNA the probe oligonucleotides are hybridized overnight to their respective targets. Only perfectly matched probes are ligated by the thermostable Ligase-65 and only ligated probes are exponentially amplified by the universal primer pair X and Y in the subsequent PCR. Finally, the amplified fragments are separated and analysed by capillary electrophoresis.

In this study we have adapted the MLPA technology by introducing three oligonucleotide MLPA probes making it possible to distinguish between homologous, non-homologous and incomplete recombination in mouse ES cell clones, targeted with two different constructs. The first construct introduces a single nucleotide exchange in the PCNA gene, while the second construct results in a conditional knockout for PCNA by using the Cre-LoxP system. A total of 400 ES cell clones were simultaneously analysed for homologous and non-homologous integration events and our modified MLPA assay proved to be an efficient, highly reliable and a quantitative alternative for current methods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Targeting constructs

Two different targeting constructs were developed using pFlexible, containing the positive/negative selectable marker puroΔtk and LoxP and FRT recombination sites (9,10). Construct pPCNAflox contains exons two, three and four of the mouse PCNA gene inserted between the LoxP recombination sites of pFlexible, allowing conditional inactivation of the gene. pPCNAflox containing the conditional PCNA gene was modified such as to derive the K164R knockin targeting construct pPCNAK164R, in which one LoxP recombination site was removed, leaving the arms of homology intact.

Targeting of ES cells

NotI-linearized targeting construct (75 µg) was electroporated (3 µF, 0.8 kV) into 4 × 107 E14 129/Ola ES cells and were grown under 1.8 µg/mL puromycin selection on lethally irradiated primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). ES cell clones were picked into 96-well plates after 11 days of drug selection, expanded and used for genomic DNA isolation. PCNA targeted ES cell clones were identified with MLPA probes specific for either the LoxP sites or the single nucleotide exchange. All 400 ES cell clones were further verified with Southern blot analysis using a 3′ external probe on BamHI digested genomic DNA.

Probe preparation

The design of the MLPA probes was performed as described by Schouten et al., 2002 (3). For this study, three completely synthetic MLPA probes (11) specific for the 5′ and 3′ LoxP recombination sequences and one specific for the K164R mismatch were designed. In contrast to ordinary MLPA probes these probes consist of three oligonucleotides, one wild-type specific 5′ phosphorylated oligonucleotide and two (one wild-type specific and one mutant specific) 3′ donating oligonucleotides. As the two oligonucleotide probe combinations result in amplification products of different lengths, this enables simultaneous detection of both wild-type and mutant sequences (Figure 1). All synthetic probes were designed to have lengths of amplification products in the range of 106 to 134 bp, an annealing temperature >65°C according to the RAW program (www.mlpa.com/Protocols.htm) and no secondary structures according to the mFOLD server (www.bioinfo.rpi.edu/applications/mfold). For probe sequences and lengths see Supplementary Table S1. In addition, 12 ordinary phage M13 derived MLPA control probes specific to different genes in the mouse genome (SALSA PM200 probemix; MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) were included serving as control probes for a proper copy number quantification. Information about the gene names, recognition sequences and ligation sites of these control probes can be obtained at www.mlpa.com.

MLPA analysis

MLPA reagents were obtained from MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands (EK1 kit) and the reactions were performed according to the manufacturers instructions. Genomic DNA (5 µl) in TE-Buffer [10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.5), 1 mM EDTA] was denatured for 5 min at 98°C. SALSA MLPA buffer (1.5 µl) and 1 fmol of each MLPA probe were added and after a brief incubation for 1 min at 95°C allowed to hybridize to their respective targets for ∼16 h at 60°C in a total volume of 8 µl. Ligation of the hybridized probes was performed for 15 min by reducing the temperature to 54°C and adding 32 µl Ligase-65 mix (3 µl Ligase buffers A, 3 µl Ligase Buffer B, 1 µl Ligase-65 and 25 µl Water). After inactivating the enzyme for 5 min at 98°C, 10 µl of the ligase mix was diluted with 30 µl 1× PCR Buffer (50 mM KCl, 20 mM Tris–HCl, 1.6 mM MgCl2 and 0.01% non-ionic detergents). While at 60°C, 10 µl of a mixture consisting of dNTPs, universal PCR primers (one D4 labeled and one unlabelled) and 2.5 U of SALSA Polymerase were added. PCR amplification of the ligated MLPA probes was performed for 33 cycles (30 s 95°C, 30 s 60°C and 1 min 72°C). Finally the PCR products were analysed on a Beckman CEQ 2000 capillary electrophoresis apparatus.

Preamplification of K164R targeted DNA

The mouse genome harbors at least two PCNA pseudogenes, making identification of homologous recombination events of the K164R mutant PCNA in the PCNA gene difficult. Therefore the genomic DNA was first amplified using PCR primers specific for intronic sequences surrounding exon four of PCNA but absent in the pseudogenes. In addition, three other primer pairs surrounding the recognition sequences of three of the control probes were included for copy number quantification. A list of the primers used can be found in Supplementary Table S2. In brief, 1 µl of genomic DNA was diluted with TE-Buffer [10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.5), 1 mM EDTA] to a total volume of 5 µl and incubated for 5 min at 98°C. While at 60°C 20 µl of a mix containing dNTPs, PCR buffer, 1 U SALSA polymerase (MRC-Holland bv, Amsterdam, NL) and 1 pmol of each primer was added. The PCR was performed for 10 cycles: 30 s at 95°C, 1.5 min at 57°C and 1 min at 72°C. Finally 0.5 µl of the PCR products was used for MLPA.

Fragment and data analysis

For copy number quantification the peak areas were exported to an Excel file. The peak area of the PCNA specific MLPA probes was normalized by dividing it by the combined areas of the control probes. Finally, this ratio was compared with the similar ratio obtained from an untargeted sample. Homologous integrations were scored when the wild-type signal is reduced by 35–60% and compensated by the appearance of the mutant signal. Samples showing >60% higher mutant specific signal as compared with the average positive clone were regarded as having multiple integrations.

Southern blotting

Genomic DNA was isolated and digested with BamHI overnight. Samples were run on a 0.6% agarose gel and blotted on Hybond-N+ (Amersham Pharmacia). The blots were prehybridized for 4 h and hybridized overnight in a buffer containing 50% formamid, 5× SSC, 5× Denhardt, 0.05 M phosphate, 5 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS and 250 µg/ml fish sperm. An external 800 bp probe located 3′ of the PCNA gene was radioactively labeled using the Prime-It® II Random Primer Labeling Kit (Stratagene). The blot was exposed on a KODAK XAR film.

RESULTS

Conventional MLPA probes recognize either wild-type or mutant alleles and consist of two specific oligonucleotides. This allows the detection of gene amplification or deletions, as well as the occurrence of mutant alleles. Normally, the appearance of a mutant allele naturally coincides with the disappearance of a wild-type allele. This does not hold true for gene targeting of ES cells, owing to non-homologous integration. To distinguish non-homologous from homologous integration a third oligonucleotide is added to form the MLPA probe. In this way both wild-type and mutant signals can be detected and quantified most accurately (Figure 1).

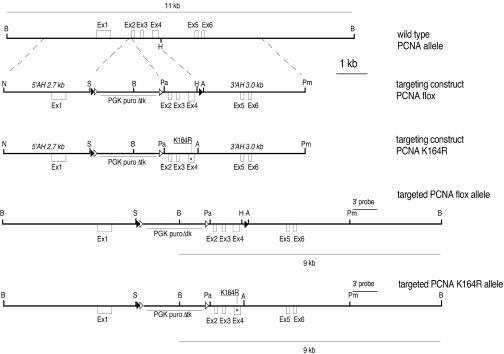

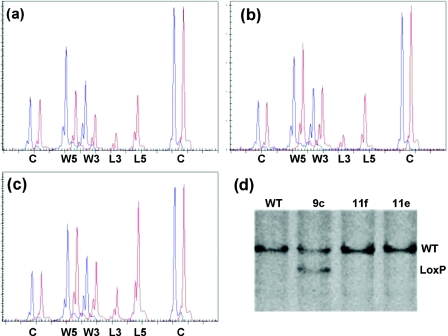

To validate MLPA as a tool to identify homologous recombination events in gene targeting, ES cells were transfected with two different targeting constructs (Figure 2). The conditional PCNA targeting construct used in this study contains a positive/negative selectable marker puroΔtk flanked by Frt recombination sites and exons two, three and four of the PCNA gene flanked by LoxP recombination sites. While Frt sites allow deletion of the selection cassette by Flp recombinase, LoxP sites allow conditional inactivation of the PCNA gene by Cre recombinase. To distinguish between homologous and non-homologous recombination events we used two PCNA WT/LoxP specific probes, recognizing the 5′ and 3′ LoxP sites, to analyse DNA samples derived from targeted and untargeted ES cell clones. Homologous integration is characterized by a reduction of 50% of the PCNA wild-type signal areas compared with the untargeted control sample, combined with the appearance of the LoxP specific signals (Figure 3a).

Figure 2.

Targeting PCNA alleles: Conditional inactivation and knockin of a K164R mutation. To inactivate wild-type PCNA conditionally, exons 2–4 (Ex2–4) were subcloned into the PacI (Pa) and HindIII (H) sites of the targeting vector pFlexible. To introduce the K164R mutation, exons 2–4 (Ex2–4) were subcloned into the PacI and AscI (A) sites of the targeting vector pFlexible. The asterisk indicates the location of the K164R mutation. A 2.7 kb fragment upstream of Ex2 was flanked by NotI (N) and SbfI (S) restriction sites and used as a 5′ arm of homology (5′AH). A 3.0 kb fragment downstream of Ex4, flanked by AscI and PmeI (Pm) sites was used as a 3′ arm of homology (3′AH). Open and closed triangles indicate Frt and LoxP recombination sites, respectively. While Frt sites allow deletion of the selection cassette, LoxP sites allow conditional inactivation of the PCNA gene. The transcriptional orientation of the PGK puroΔtk selection cassette is indicated by an arrow. An external 3′ probe (0.8 kb) was used for Southern blot analysis. A 11 kb and a 9 kb BamHI (B) fragment are indicative of the wild-type and the targeted allele(s), respectively.

Figure 3.

Identification of homologous and non-homologous recombination for the conditional inactivation of PCNA with MLPA. DNA extracted from targeted and untargeted ES cell clones was analysed by MLPA using a probe mix containing 12 copy number control probes (C) and two MLPA probes specific for both the 5′ and 3′ wild-type (W5 and W3) and LoxP recombination sites (L5 and L3). Only part of the capillary electrophoresis (CE) pattern is shown. (a) CE pattern obtained from untargeted ES cell DNA (blue, WT) and DNA from a homologous recombined ES cell clone (red, 9c). A 50% reduction in both the 5′ (114 bp) and the 3′ (120 bp) wild-type specific signals and the appearance of both 3′ (127 bp) LoxP and the 5′ (134 bp) LoxP specific signals can be seen. (b) CE pattern obtained from a non-homologous recombination. No change is observed in the wild-type specific signals but mutant specific signals appear in the targeted ES cell clone (red, 11f) compared with the control DNA. (c) Two non-homologous integrations can be identified by the 100% increase in the mutant signals compared with the average single integration (red, 11e). (d) Verification of the MLPA results with Southern blot analysis on BamHI digested genomic DNA using an external 3′ probe. Wild-type allele: 11 kb, Conditional allele: 9 kb. (WT) Untargeted ES cells. (9c) Homologous integration. (11e+f) Non-homologous integrations.

Non-homologous integration on the other hand, generated 5′ and 3′ LoxP specific signal areas, with no change in wild-type signal area (Figure 3b). Double integrations were also detected, as seen in Figure 3c. In the latter case the construct has integrated twice, both in non-homologous manner, since the wild-type signal areas still correspond to two alleles (100%), together with LoxP specific signal areas also corresponding to two alleles. A quantitative analysis of these MLPA results is shown in Supplementary Figure S1.

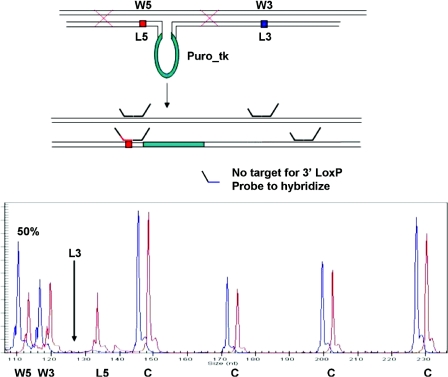

Incomplete integration of the targeting construct

The existence of non-homologous regions such as a selection cassette within the targeting construct can result in incomplete recombination. The region of non-homology within our targeting construct is rather large in comparison with the arms of homology: 2.4 kb for the selection marker in comparison with 2.7 and 3.0 kb of the 5′ and 3′ arms of homology. In line with these considerations incomplete integrations have been identified, based on the loss of a second LoxP recombination site (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Example of an incomplete homologous recombination event detected by MLPA. Representation of an incomplete homologous recombination event observed for the conditional inactivation of the PCNA gene. In green: the puroΔtk selection marker. Incomplete recombination is revealed by the absence of one of the two LoxP recombination sites (L3). The MLPA probe mix contained 12 control probes (C) and two probes specific for the 5′ and 3′ wild-type and LoxP recombination sites. Only part of the CE pattern is shown. In blue the CE pattern of untargeted ES cell clone, in red the CE pattern of an ES cell clone with an incomplete integration.

Validation by Southern blot analysis

Homologous integration of all ES cell clones as identified by the MLPA assay, was verified by Southern blotting using a 800 bp 3′ external probe (Figure 3d). Homologous integration of the targeting construct will result in the wild-type 11 kb band, with the additional appearance of a 9 kb band, owing to the introduction of a BamHI restriction site present in the puroΔtk region of the targeting construct. Southern blot analysis of all 400 ES cell clones tested, revealed no false positive or false negative results for any of the probes used in the MLPA analysis (data not shown). In total, four positive clones were detected by MLPA and confirmed by Southern blot analysis.

Preamplification of K164R targeted DNA

The mouse genome harbors at least two PCNA pseudogenes, hampering identification of homologous recombination events of the K164R mutant PCNA in the PCNA gene. Before MLPA analysis, the PCNA exon four genomic DNA was amplified using PCR primers specific for intronic sequences surrounding exon four of PCNA. As these sequences are absent in the pseudogenes, only the wild-type PCNA sequence will be amplified. In the same PCR the sequences detected by three of the control probes were also amplified. As shown in Figure 5 homologous integration could easily be identified by MLPA using the preamplified DNA as target for the MLPA probes, by the 50% reduction in the wild-type specific signal and the appearance of the mutant specific signal in the targeted ES clone as compared with untargeted. In addition, the disappearance of the non-amplified control probes indicates that only the amplified sequences are detected.

Figure 5.

Identification of homologous recombination of PCNAK164R targeted ES cells using preamplification MLPA. Schematic overview of the PCR strategy for the out-competition of intronless PCNA pseudogenes by using intron specific primers. In addition, three primer pairs were added for the amplification of the DNA regions recognized by the control probes C4–C6. Capillary electrophoresis pattern obtained from untargeted ES cell DNA (blue) and DNA from a homologous recombined K164R ES cell clone (red). A 50% reduction in the 116 bp wild-type specific signal and appearance of the 106 bp mutant specific signal in the targeted ES cell clone is observed when compared with untargeted ES cell DNA.

DISCUSSION

Mouse models can be generated using different methods, conventionally by gene targeting or by oligonucleotide targeting of ES cells. Both of these methods rely on the homologous integration of a stretch of foreign DNA (construct or oligonucleotide) to modify the genome. Use of the MLPA technique for the identification of homologous integration is a promising alternative for the commonly used Southern blotting and PCR methods. In this study we validate this method by analysing single clones from mouse ES cells targeted with two different constructs. The first construct results in a conditional knockout for PCNA by use of the Cre-LoxP system, and the second construct introduces a single nucleotide exchange in the PCNA gene.

We have adapted MLPA such that we can distinguish between homologous and non-homologous recombination. This is achieved by using a three oligonucleotide probe, rather than a two oligonucleotide probe: one mutual phosphorylated probe and two probes recognizing either wild-type or mutant sequence. While the wild-type and mutant specific oligonucleotide probes for the detection of the integration of the conditional knockout construct anneal to completely different sequences, the recognition sequences for the wild-type and mutant specific K164R differ only in a single nucleotide in their target sequence. The specific sensitivity of the Ligase-65 prevents ligation of mismatched oligonucleotides, making this small distinction possible (12). In this study we show that several hundred ES cell clones can easily, rapidly and quantitatively be analysed by MLPA for both homologous and non-homologous integration of the targeting construct. Not only could we detect the ES cell clones with the homologous integration, but also clones with incomplete and multiple integrations were easily identified. In addition, no false positive or false negative results were obtained in the MLPA assay.

Major advantages of MLPA over Southern blotting and PCR for the screening of targeted ES cells are (i) changes as small as single nucleotide exchanges can be studied using a minimum of 20 ng sample DNA, (ii) owing to its simple procedure, large numbers of samples can be analysed simultaneously with a minimum of hands on work and (iii) MLPA is quantitative and can discriminate between homologous, non-homologous and incomplete recombination events. Multiple integrations can be identified as well. Owing to its simplicity, the MLPA method described here can be handled in a 96-well format and may therefore serve as a powerful high throughput tool. Even though some time is required for probe design as with Southern blotting, and extra costs for synthesis of phosphorylated oligonucleotides, the time earned (incomplete digestion, too low DNA concentrations, Southern blotting, false positives, etc.) clearly outweighs the negative aspects. In addition, by using MLPA preceded with preamplification of the target DNA, ES cells with homologous integration in a large population of non-integrated cells can be identified, which should facilitate high throughput screening of ES cells targeted with single nucleotide exchanges using the oligonucleotide targeting method as mentioned previously.

MLPA can be used not only for the detection of homologous integration events in conventionally targeted ES cell clones, but also provides a powerful tool in bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) recombineering, transgenesis and targeting. In BAC recombineering phage-based homologous recombination systems are used to create targeting vectors without the use of conventional restriction enzymes or DNA ligases (reviewed by 13). To verify that the modifications are present in the newly derived targeting vector, a combination of Southern blot analysis as well as PCR strategies are required. MLPA can serve as a suitable alternative of these methods, especially when creating large numbers of new targeting vectors, such as suggested for the mouse knockout project (14).

Several groups have used BACs to develop transgenic mice and look for gene-dosage effects of certain genes (15–17). Antoch et al. generated transgenic mice by pronuclear injection of different BACs containing the same gene. To identify transgenic mice they use PCR of the BAC vector-insert junctions and Southern blot analysis using probes specific for either the BAC vector or for genomic sequences within the clone. Young and Seed on the other hand used a combination of PCR and FISH to identify site-specific gene targeting in ES cells with intact BACs (18). Since MLPA detects copy number of specific sequences, BAC transgenic mice can easily be identified in one simple reaction.

In conclusion, MLPA is a fast, simple, reliable and quantitative alternative for the characterization of clones obtained by recombineering. Homologous and non-homologous recombination events can easily be detected regardless of the size of the targeting construct (conventional, oligonucleotide or BAC).

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Sylvia Lens for expert technical assistance, and Abdellatif Errami and Mark Entius for reviewing the manuscript. Financial support was obtained from The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (VIDI program 917.56.328 to H.J.). P.L. is supported by a startup grant from the Netherlands Cancer Institute (2.129 SFN to H.J.). Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (Prg. Number 917.56.328).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Thomas K.R., Capecchi M.R. Site-directed mutagenesis by gene targeting in mouse embryo-derived stem cells. Cell. 1987;51:503–512. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90646-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dekker M., Brouwers C., te Riele H. Targeted gene modification in mismatch-repair-deficient embryonic stem cells by single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:e27. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schouten J.P., McElgunn C.J., Waaijer R., Zwijnenburg D., Diepvens F., Pals G. Relative quantification of 40 nucleic acid sequences by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e57. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnf056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eldering E., Spek C.A., Aberson H.L., Grummels A., Derks I.A., de Vos A.F., McElgunn C.J., Schouten J.P. Expression profiling via novel multiplex assay allows rapid assessment of gene regulation in defined signalling pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:e153. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nygren A.O., Ameziane N., Duarte H.M., Vijzelaar R.N., Waisfisz Q., Hess C.J., Schouten J.P., Errami A. Methylation-specific MLPA (MS-MLPA): simultaneous detection of CpG methylation and copy number changes of up to 40 sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e128. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kluwe L., Nygren A.O., Errami A., Heinrich B., Matthies C., Tatagiba M., Mautner V. Screening for large mutations of the NF2 gene. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2005;42:384–391. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slater H.R., Bruno D.L., Ren H., Pertile M., Schouten J.P., Choo K.H. Rapid, high throughput prenatal detection of aneuploidy using a novel quantitative method (MLPA) J. Med. Genet. 2003;40:907–912. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.12.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Worsham M.J., Pals G., Schouten J.P., Van Spaendonk R.M., Concus A., Carey T.E., Benninger M.S. Delineating genetic pathways of disease progression in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:702–708. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.7.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Weyden L., Adams D.J., Harris L.W., Tannahill D., Arends M.J., Bradley A. Null and conditional semaphorin 3B alleles using a flexible puroDeltatk loxP/FRT vector. Genesis. 2005;41:171–178. doi: 10.1002/gene.20111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Y.T., Bradley A. A new positive/negative selectable marker, puDeltatk, for use in embryonic stem cells. Genesis. 2000;28:31–35. doi: 10.1002/1526-968x(200009)28:1<31::aid-gene40>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White S.J., Vink G.R., Kriek M., Wuyts W., Schouten J., Bakker B., Breuning M.H., den Dunnen J.T. Two-color multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification:detecting genomic rearrangements in hereditary multiple exostoses. Hum. Mutat. 2004;24:86–92. doi: 10.1002/humu.20054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tong J., Cao W., Barany F. Biochemical properties of a high fidelity DNA ligase from Thermus species AK 16D. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:788–794. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.3.788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Copeland N.G., Jenkins N.A., Court D.L. Recombineering: a powerful new tool for mouse functional genomics. Nature Rev. Genet. 2001;2:769–779. doi: 10.1038/35093556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Austin C.P., Battey J.F., Bradley A., Bucan M., Capecchi M., Collins F.S., Dove W.F., Duyk G., Dymecki S., Eppig J.T., et al. The knockout mouse project. Nature Genet. 2004;36:921–924. doi: 10.1038/ng0904-921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antoch M.P., Song E.J., Chang A.M., Vitaterna M.H., Zhao Y., Wilsbacher L.D., Sangoram A.M., King D.P., Pinto L.H., Takahashi J.S. Functional identification of the mouse circadian Clock gene by transgenic BAC rescue. Cell. 1997;89:655–667. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80246-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang X.W., Wynder C., Doughty M.L., Heintz N. BAC-mediated gene-dosage analysis reveals a role for Zipro 1 (Ru49/Zfp38) in progenitor cell proliferation in cerebellum and skin. Nature Genet. 1999;22:327–335. doi: 10.1038/11896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu W., Misulovin Z., Suh H., Hardy R.R., Jankovic M., Yannoutsos N., Nussenzweig M.C. Coordinate regulation of RAG1 and RAG2 by cell type-specific DNA elements 5′ of RAG2. Science. 1999;285:1080–1084. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5430.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang Y., Seed B. Site-specific gene targeting in mouse embryonic stem cells with intact bacterial artificial chromosomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:447–451. doi: 10.1038/nbt803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.