Abstract

Objective

To summarise the evidence on the effect of psychological coping styles (including fighting spirit, helplessness/hopelessness, denial, and avoidance) on survival and recurrence in patients with cancer.

Design

Systematic review of published and unpublished prospective observational studies.

Main outcome measures

Survival from or recurrence of cancer.

Results

26 studies investigated the association between psychological coping styles and survival from cancer, and 11 studies investigated recurrence. Most of the studies that investigated fighting spirit (10 studies) or helplessness/hopelessness (12 studies) found no significant associations with survival or recurrence. The evidence that other coping styles play an important part was also weak. Positive findings tended to be confined to small or methodologically flawed studies; lack of adjustment for potential confounding variables was common. Positive conclusions seemed to be more commonly reported by smaller studies, indicating potential publication bias.

Conclusion

There is little consistent evidence that psychological coping styles play an important part in survival from or recurrence of cancer. People with cancer should not feel pressured into adopting particular coping styles to improve survival or reduce the risk of recurrence.

What is already known on this topic

Survival from cancer is commonly thought to be influenced by a person's psychological coping style

Some studies have shown that a coping style involving fighting spirit rather than helplessness/hopelessness is associated with survival and recurrence, though the evidence is inconsistent

What this study adds

This systematic review suggests that there is no consistent association between psychological coping and outcome of cancer

Publication bias and methodological flaws in some of the primary studies may explain some of the previous positive findings

There is no good evidence to support the development of psychological interventions to promote particular types of coping in an attempt to prolong survival

Introduction

It is a popular belief that psychological factors can influence survival from cancer, particularly breast cancer.1 Current research interest in this subject stems from 1979 when a small UK study found that a psychological coping style characterised by a “fighting spirit” was associated with longer survival from breast cancer. A more negative style of coping characterised as “helplessness/hopelessness” has also been reported to predict a poorer outcome, though not all studies have found such an association.2–6 It is important to know whether these psychological factors do have an influence on survival because psychological interventions have been developed to enhance the use of certain coping styles to prolong survival, and there is strong lay and professional support for such therapies.7

Such as association is biologically plausible, and several possible mechanisms have been proposed—for example, through immunological and neuroendocrine mechanisms.2,8 However there are conflicting views regarding the importance of coping styles in the progression of cancer, ranging from the view that they have an important influence to the view that the theory is characterised by myth and anecdote.9,10

We carried out a comprehensive systematic review to assess the strength of the evidence for an association between psychological coping and cancer outcome.

Methods

Search strategy—Following systematic review guidelines11,12 we searched several databases for published and unpublished studies (in any language) on the association between progression of cancer, recurrence or survival, and psychological coping: Medline 1966-June 2002, PsycINFO 1887-June 2002, ASSIA 1987-June 2002, Embase 1980-June 2002, Cancerlit 1966–June 2002, Dissertation Abstracts 1975-June 2002, the NLM gateway (accessed 21 June 2002), and CINAHL 1982-June 2002. We searched bibliographies and reviews and contacted key individuals and authors for additional unpublished information when necessary.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria—We included prospective cohort studies that included mortality, survival, or recurrence as outcomes. We excluded studies of the association between coping and immune responses or other biochemical markers, if this was the only outcome reported, and studies of personality types (for example, “type C” personality).

Data extraction and validity assessment—When the results of both multivariate analyses and univariate analyses were presented we extracted data from the multivariate analysis and noted the variables used in the adjustment (table 1 and 2). When necessary we contacted authors for unpublished data; one author supplied the requested information. Data were extracted by one reviewer and checked by a second. The studies were assessed independently by two reviewers against three methodological criteria: whether the sample represented an inception cohort, the degree of adjustment for potential confounders, and whether the assessment of coping was carried out early in the disease process. The results were summarised narratively.

Table 1.

Prospective studies of survival from cancer and coping style* (posted as supplied by authors)

| Sample size (% women); mean age at entry (years) | Coping style(s) (scale used) | Site of cancer | Length of follow up (No of deaths) | Adjustment for confounders/ examination of baseline variables† | Results | Summary of results‡ | Summary of key methodological aspects of study§ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achté (1979)30 Finland | 126 (sex, age not stated) | Denial, repression | Not stated. Malignancies of digestive system or urinary tract excluded | Up to 3 years (35) | None | Poorer survival associated with denial and isolation, regression and aggression; no data presented | + | 1, 3 |

| Andrykowski (1994)13 USA |

42 (38%); 34 years | Fighting spirit, hopelessness/ helplessness, anxious preoccupation, fatalism and avoidance (MAC48) | Chronic or acute leukaemia, patients undergoing bone marrow transplant | Median survival 2.2 months (27) | Quality of graft match, diagnosis, age, time from diagnosis to transplant, stage, sex, education | MAC anxious preoccupation score associated with poorer survival (adjusted Cox RR=1.2, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.3). Univariate HR for other MAC scores: fighting spirit 1.01 (0.95 to 1.1); helplessness/ hopelessness 0.92 (0.8 to 1.1); fatalism 0.99 (0.9 to 1.1) | − | 1,2,3 |

| Brown (2000)8 Australia |

426 (39%); 53 years | Active, distractive, and avoidant coping; adjustment to cancer | Early stage melanoma | 2 years (60) | Clinical, demographic, and psychological factors | Higher avoidant coping scores did not independently predict survival: HR=1.02 (1.00 to 1.05, P=0.08). Other coping styles: not stated | − | 1,2,3 |

| Buddeberg (1990, 1991, 1996, 1997)34-37 Switzerland /Germany |

107 (100%); 53 years | Depressive coping, distrust and pessimism, “regressive tendency”, self encouragement, distraction, self revalorisation, control of feelings and withdrawal, problem solving (Zurich coping questionnaire56 57) | Patients with breast cancer without metastases who had undergone surgery 6 months earlier | 3 years; 5-6 years; and 10 years (31) | 3 years: none 5-6 and 10 years: tumour size, node status, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, age |

3 years: correlations between coping and death or metastases, self rated coping (r=−0.04, NS); depressive coping (r=−0.01, NS); self encouragement/distraction (r=−0.05, NS); problem tackling (r=−0.11, NS) 5-6 and 10 years: coping styles not related to outcome |

− | 1, 3 (at 3 years) 1,2,3 (at 5-6, 10 years) |

| Butow (1999)27 Australia |

125 (38%); 55 years | Active, distractive, and avoidant coping | Metastatic melanoma | 2 years (deaths not stated) | Range of demographic, treatment, and clinical variables considered for inclusion in MVA | Coping scores did not independently predict survival. Univariate HR: active coping 0.99 (0.96 to 1.03); distractive coping 1.01 (1.03 to 1.2); avoidant coping 0.98 (0.9 to 1.1); minimisation predicted survival 0.93 (0.87 to 0.99) | − | 1,2,3 |

| Butow (2000)28 Australia |

99 (100%); 57 years | Active, distractive and avoidant coping; adjustment to cancer (stigma/isolation, minimisation, anger) | Metastatic breast cancer | 2 years (62) | Age, sex, marital status, time since diagnosis, tumour site and thickness, ulceration, mitoses, treatment, tumour site | Patients who minimised impact of cancer on social, work, and family lives survived longer (HR 0.93 (0.88 to 0.98); coping factors not significant | − | 1,2,3 |

| Cassileth et al. (1985, 1988) 22 USA |

Group I: unresectable cancers; n=204 (37%); 60 years Group II: n=155 (80%); 52 years |

Hopelessness/ helplessness, amount of adjustment required to cope |

Group I: pancreatic, gastric, lung, colorectal cancer, or glioma Group II: melanoma or breast cancer |

1985: group I median survival 7 months; group II median 12 months to recurrence 1988: follow up at 3-8 years (191 deaths) |

1985: no adjustment; no baseline clinical differences 1988: diagnosis, disease extent, performance status, marital status, age group |

1985: no association of coping scores with survival time (Mantel Cox=1.3, P>010) Hopelessness/helplessness: 4.2 (group 1), 3.9 (group II) 1988: (group I—high adjustment associated with risk of death: RR=1.6 (1.1 to 2.3). Hopelessness not significant; no data |

− | 1,3 (1985) 1,2,3 (1988) |

| Cody (1994)14 UK |

209 (29%); 64 years (median) | Fighting spirit , helplessness, anxiety, fatalism, avoidance48 | Patients with new diagnosis of inoperable lung cancer | 8 weeks (deaths not stated) | Multivariate analysis carried out; variables not stated | No adjusted association between denial, stoic acceptance, helplessness, hopelessness, fighting spirit scores, and survival. No other data | − | 1,2 |

| Dean and Surtees (1989)15 UK | 125 (100%); 49 years | Stoic acceptance, fighting spirit, denial, hopelessness/ helplessness, anxious/ depressed51 | Primary breast cancer | 6-8 years (22) | Age, social class, marital status, menopausal status, employment, tumour size, node status | Patients employing denial survived longer; P<0.1; no other data | − | 1,2,3 |

| De Boer (1998)49 Netherlands |

133 (16%); 63 years (median) | Uncertainty regarding how to cope with illness or emotions50 | Head, neck Stage I: 48% Stage II: 13% Stage III: 23% Stage IV: 21% |

6 years (57) | Prior radiotherapy, T and N classification, age, education, marital status, smoking, drinking | High uncertainty scores predicted shorter survival. Uncertainty regarding coping with practical aspects of illness (adjusted RR=1.11, 1.04 to 1.2); uncertainty regarding coping with emotions (0.93, 0.85 to 1.01) | + | 2,3 |

| Derogatis (1979)38 USA |

35 (100%); 55 years | Anxiety, depression, hostility, guilt, psychoticism, psychological symptom severity (defined by authors as coping styles) | Metastatic breast cancer | Long term survivors (mean=23 months) v short term survivors (mean=9 months) (13) | None. No baseline differences in age, disease-free interval, % premenopausal, metastases, Karnofsky score, response to therapy | Survivors v non-survivors: hostility (t=2.4, P<0.01), psychoticism (t=2.7, P<0.01), depression (t=2.3, P<0.05), guilt (t=2.6, P<0.05), negative affect (t=2.7, P<0.01), affect balance (t=2.1, P<0.05) | + | 3 |

| Faller (1997; 1999; and unpublished data)39 40 Germany |

103 (17%); 59 years | Depressive coping, active coping, hope35 57 | Lung cancer Stage 1: 2%, Stage II: 7% Stage IIIa/IIIb: 49% Stage IV: 42% |

(i) 3-5 years (ii) 5-7 years (92) |

(i) Karnofsky status, treatment, stage (ii) Histology, stage, Karnofsky status, treatment |

Use of active coping predicted longer survival (3-5 years RR=1.91, 1.17 to 3.12; also 5-7 years RR=0.68, 0.50 to 0.94). Use of depressive coping predicted shorter survival (RR=1.88, 1.29 to 2.73) | + | 1,2,3 |

| Giraldi (1997)16 Italy |

95 (100%); 51 years | Fighting spirit, hopelessness, anxious preoccupation, fatalism48 | Breast cancer T1: 36% T2: 41% |

6 years (15) |

Nodal status, histology, tumour stage, oestrogen receptor status | High v low fighting spirit score: RR=1.08, 0.94 to 1.23 High v low hopelessness score: unadjusted RR=0.9, 0.72 to 1.12; no other data |

− | 1,2,3 |

| Greer (1979),2 Pettingale (1984),3 Pettingale (1985),4 Greer (1990)5 UK |

69 (100%); aged <70 years | Denial, fighting spirit, stoic acceptance, helplessness/ hopelessness | Breast cancer with no metastases | 5, 10, 15 years (34, 36, 47) |

5 years: none 10 years: age, menopausal status, stage, operation, radiotherapy, histology 15 years: age, menopausal status, stage, operation, radiotherapy, histology |

5 years: use of stoic acceptance or helplessness/ hopelessness and risk of death RR=4.4, 1.1 to 17.0) 10 years: use of denial or fighting spirit predicted death, and death from breast cancer (P=0.003) 15 years: denial, fighting spirit predicted death (z=2.83, P=0.006), death from cancer (z=3.6, P<0.001) |

+ + + |

1,3 (at 5 years) 1,2,3 (at 10 years) 1,2,3 (at 10 years) |

| Hislop (1987)41 Canada |

133 (100%); <55 years at diagnosis | Coping by change, by control, by stress | Primary ductal breast cancer | 4 years (26) |

Age, stage, pathological nodal status, histological grade, ER status | Coping by change (more v less often): Cox adjusted RR=0.59, no CI, P=0.3 Coping by control: RR=0.59 Coping by stress: RR=1.4, P=0.6 | − | 1,2,3 |

| Molassiotis (1997)23 UK | 31 (29%); 34 years | Emotion focused coping, humour, withdrawal, acceptance, hopefulness (Jalowiec coping scale52) | Patients with bone marrow transplant: haematological malignancies | 1-2 years (20) | Age, sex, marital status, ethnicity, diagnosis, quality of raft match, stage, previous treatment | Frequent use of hope (Cox adjusted RR=0.11, 0.02 to 0.52) and less frequent use of acceptance (1.4, 1.3 to 13.4) predicted long term survival | + | 1,2,3 |

| Morris (1992)6 UK | 107 (100%) 61 (26%) |

Denial, fighting spirit, anxious preoccupation, stoic acceptance, helpless/hopelessness | Breast cancer (n=107) Lymphoma (n=61) |

Up to 5 years (20) | Age, sex, stage, tumour grade, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, type of operation, tumour size, positive nodal status | Breast cancer: no coping style predicted survival Lymphoma: anxious preoccupation/stoicism/ helplessness-hopelessness associated with survival. All cases: association found between “prognostic index” and primary coping style (χ2 for survival 5.49, P=0.02) |

− (breast cancer) + (lymphoma) + (all cases) |

1,2 |

| Murphy (1996)17 UK | 56 (48%); 35 years | Fighting spirit , helplessness, anxiety, fatalism, avoidance48 | Patients with bone marrow transplant: leukaemia: 68% lymphoma: 25% aplastic anaemia: 8% |

Mean follow up: 82 months (18) | Unadjusted | No difference in mean survival time between patients with fighting spirit as predominant coping style and others (P=0.79; no other data). | − | 1,3 |

| Nordin and Glimelius (1997, 1998)18 19 Sweden | 139 (51%); 67 years | Fighting spirit, helplessness, anxious preoccupation, anxiety, fatalism, avoidance48 | Gastrointestinal cancers (colon: 27%, rectum: 23%, gastric: 24%, pancreatic: 16%, biliary: 12%) | ⩽ 12 months (56) | No adjustment; cured and non-cured patients did not differ in age, time since diagnosis, or sex | At 6 months: fighting spirit as predominant style RR=0.86, 0.61 to 1.19); helplessness/ hopelessness 1.19, 0.84 to 1.69); anxious preoccupation 1.03 (0.7 to 1.5); fatalism 0.88, 0.56 to 1.39) | − | 1,3 |

| Reynolds (2000)1 USA | 847 (100%) | Expressing/suppressing emotions, wishful thinking, problem solving, positive reappraisal, avoidance, escapism, size of “coping repertoire” | Breast cancer | Up to 9 years after diagnosis (218) | Age, study location, race, stage, comorbidity, weight, progesterone and oestrogen receptor status | Expressing emotions increased survival (HR=0.6, 0.4 to 0.9); suppression reduced survival (1.4, 1.1 to 1.9); wishful thinking 0.9, 0.7 to 1.3); problem solving 0.8, 0.6 to 1.2); positive reappraisal 1.1, 0.7 to 1.6); avoidance 0.8, 0.6 to 1.1); escapism 1.1, 0.7 to 1.5). HRs refer to high v low use of coping style | +/− | 1,2,3 |

| Richardson (1990)29 USA | 139 (35%); from <20 to ⩾80 years | Behavioural and cognitive coping, including avoidance, information seeking, problem solving, affective regulation53 | Haematological malignancies (n=92) Rectal cancer (n=47) |

4 years 10 months (rectal cancer); ⩽5 years (haematological cancers) (64) | Unadjusted | No significant association with outcome in either group. RR for high v low avoidance: (i) 1.08, 0.32 to 2.44; (ii) 0.71, 0.32 to 1.62) | − | 1,3 |

| Ringdal (1995),25 (1996)24 USA | 253 (45%); 57 years | Hopelessness (Beck hopelessness scale54) | Breast: (25%) Gastrointestinal: (11%) Prostate: 12% Lung: 11%) Lymphomas: 13% |

Mean survival time 7 months (131) | Age, sex, treatment intention, physical functioning, cancer type, treatment modality, relapse | Cox unadjusted RR for hopelessness 1.11, 1.06 to 1.17). Association disappeared in multivariate analysis | − | 2,3 |

| Schulz (1996)55 USA |

268 (51%); >30 years | Pessimism, optimism | Recurrent/ metastasised breast: 23% Lung: 20% Head/neck: 13% Gynaecological: 9% Other cancers |

8 months (70) | Type of cancer, symptoms at baseline | No direct or indirect effects of optimism score on mortality. Pessimism score did not independently predict mortality (adjusted RR=1.1, 0.97 to 1.2) | − | 2,3 |

| Silberfarb (1991)31 USA | 290 (46%); 13% <49 years 27% <59 years 33% <69 years |

Denial of illness | Previously untreated patients with multiple myeloma | 2 years (deaths not stated) | Age, tumour cell load, creatinine, “usual prognostic factors” | No association of denial with survival; no other data | − | 1,3 |

| Tschuschke (2001)20 Germany | 52 (31%); 36 years | Passive reception/resignation, distraction, cognitive structuring, social contact, compliance, fighting spirit | Patients with acute (n=33) and chronic (n=19) myeloid leukaemia undergoing bone marrow transplantation | Mean survival time 2.6 years (21) | Stage, leukaemia type, age, sex. Distraction, fighting spirit subgroups similar in education, marital status, social support, GvHD prophylaxis | Distraction (Wald=7.27, P=0.007), fighting spirit (6.31, P<0.012) associated with survival. RRs estimated from survival curve: high v low distraction 0.61; high v low fighting spirit 0.65 | + | 2,3 |

| Watson (1999)7 UK |

578 (100%); 55 years | Fighting spirit, helplessness/hopelessness, anxious preoccupation, fatalism, avoidance (MAC scale48), emotional suppression | Stage I and II breast cancer | 5 years (133) | Histopathological grade, number of +ve lymph nodes, tumour size, type of operation, chemotherapy v endocrine therapy, oestrogen receptor status | No effect of predominant coping style, or emotional suppression. Fighting spirit HR=0.86, 0.42 to 1.76; H/H 0.95, 0.46 to 1.98; anxiety preoccupation 1.04, 0.5 to 2.2; fatalism 1.02, 0.49 to 2.15; avoidance 1.53, 0.72 to 3.28) | Mainly negative | 1,2,3 |

RR=relative risk; HR=hazard ratio; NS=non-significant.

Some studies investigated both survival and recurrence and therefore appear in table 2 also.

In addition to psychosocial variables.

+=mainly significant associations found; 0=no significant associations; +/−=mixed positive and negative findings.

1=patients recruited near to diagnosis; 2=adjustment for at least one confounder; 3=early assessment of coping style.

Table 2.

Prospective studies of recurrence of cancer and coping style* (posted as supplied by authors)

| Sample size (% women); mean age at entry (years) | Coping style(s) (scale used) | Site of cancer and stage | Length of follow up | Adjustment for confounders/ examination of baseline variables† | Results | Summary of results‡ | Summary of key methodological aspects of study§ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown (2000)8 Australia |

426 (39%); 53 years | Active, distractive and avoidant coping; adjustment to cancer (stigma/isolation, minimisation, anger) | Early stage melanoma | 2 years | Clinical, demographic, and psychological factors | Avoidant coping scores and recurrence: HR=1.02, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.04, P=0.03. Other coping styles not stated | + | 1,2,3 |

| Cassileth (1985, 1988)21 22 USA |

Group I: unresectable cancers; n=204 (37%); 60 years Group II: stage I/II melanoma, stage II breast cancer; n=155 (80%); 52 years | Hopelessness/ helplessness,38 amount of adjustment required to cope with diagnosis | Group I: unresectable pancreatic, gastric, non-small cell lung cancer, colorectal cancer, or grade 3 or 4 glioma Group II: melanoma or breast cancer |

1985: group I: median survival 7 months); group II: time to recurrence 12 months. 1988: 3-8 years | 1985: unadjusted. 1988: diagnosis, disease extent, performance status, marital status, age group | 1985: recurrence, no unadjusted association of psychosocial categories with recurrence (Mantel Cox statistic=4.4, P>0.10). 1988: time to recurrence (group II): “intermediate” level of hopelessness: Cox RR=0.52, 0.28 to 0.96, P=0.03 (adjusted for psychosocial variables only) | − + |

1,3 (1985) 1,2,3 (1988) |

| Dean and Surtees (1989)15 UK |

125 (100%); 49 years | Stoic acceptance, fighting spirit, denial, hopelessness/ helplessness, anxious/depressed51 | Primary breast cancer | 6-8 years | Age, social class, marital status, menopausal status, employment, tumour size, node status | Patients who employed hopelessness/helplessness and stoic acceptance were more likely to be recurrence-free at follow up; use of denial at 3 months associated with being recurrence free; no other data. | + | 1,2,3 |

| De Boer (1998)49 Netherlands |

133 (16%); 63 years (median) | Uncertainty regarding how to cope with illness, or emotions50 | Head, neck cancer. Patients received radiotherapy, laryngectomy, or other surgery. Stage I: 48%, II: 13%, III: 23%, IV: 21% | 6 years | Previous radiotherapy, T and N classification, age, education, marital status, smoking, drinking | Higher uncertainty regarding coping with practical aspects of illness (adjusted RR for uncertainty score=1.03, 0.96 to 1.11); uncertainty regarding coping with emotions (0.98, 0.90 to 1.07) | + | 2,3 |

| Epping-Jordan (1994)32 USA |

66 (72%); 41 years | Avoidance (impact of events scale)58 | Breast (38%), gynaecological (19%), haematological (14%), brain (9%), malignant melanoma (5%) | 1 year | Age, severity, physician's prognosis, number of treatments, distress | High avoidance score predicted poorer disease status (composite variable including recurrence) at 1 year (adjusted OR=0.81, P=0.19) | + | 1,2,3 |

| Greer (1979)2 Pettingale (1984),3 Pettingale (1985),4 Greer (1990)5 UK |

69 (100%); <70 years | Denial, fighting spirit, stoic acceptance, helplessness/ hopelessness | Breast cancer with no metastases, treated by mastectomy; 25 also received radiotherapy | 5, 10, and 15 years | 5 years: none. 10 years: age, menopausal status, stage, operation, radiotherapy, histology. 15 years: age, menopausal status, stage, operation, radiotherapy, histology | 5 years: recurrence or death. Use of denial RR=1.57, 0.94 to 2.62, fighting spirit 1.88, 1.19 to 2.96, and either coping strategy v acceptance or helplessness/hopelessness 3.1, 1.3 to 7.4. 10, 15 years: use of denial or fighting spirit predicted recurrence | + | 1,3 (at 5 years) 1,2,3 (at 10 years) 1,2,3 (at 10 years) |

| Hislop (1987)41 Canada |

133 (100%); <55 years at diagnosis | Coping by change, by control, by stress | Primary ductal breast cancer | 4 years | Age, stage, pathological nodal status, histological grade, ER status | No effect of coping variables (high v low use of coping style) on recurrence. Coping by change Cox adjusted RR=0.6, no CI, P=0.12; coping by control 0.95, P=0.9; coping by stress 1.1, P=0.8 | − | 1,2,3 |

| Jensen (1987)26 USA |

Group I: women with recurrence or metastasis (n=27; 50 years); group II: women with minimum 2 years in remission (n=25; 49 years); group III: non-cancer controls (n=34, age not given) | Defensiveness, helplessness/ hopelessness, negative affect, chronic stress, and daydreaming (Millon behavioural health inventory, MBHI26) |

Breast cancer | Average follow up 624 days | Groups similar in stage, age, weight, age at menarche, and first pregnancy, parity, SES, family history, disease course, positive nodes. Adjusted for age, stage, cancer duration, packed cell volume, alkaline phosphatase | Defensiveness (presence v absence) F=4.4, P=0.04; helplessness/hopelessness score F=9.6, P=0.0006; negative affect score F=2.2, P=0.004; chronic stress F=5.7, P=0.02; and daydreaming score F=10.4, P=0.003, were independently associated with clinical and vital status (composite variable based on final disease status) | + | 1,2 |

| Morris (1992)6 UK |

107 (100%) 61 (26%) | Denial, fighting spirit, anxious preoccupation, stoic acceptance, helpless/hopelessness | Breast cancer (n=107); lymphoma (n=61) | Up to 5 years | Age, sex, stage, tumour grade, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, type of operation, tumour size, nodal status | Breast cancer, lymphoma: no coping style predicted recurrence. All: association between prognostic index and style of coping (χ2 for recurrence=6.1, P=0.02) | − | 1,2 |

| Rogentine (1979)33 USA |

Study 1: 67 (25%); 16-67 years | Adjustment needed to cope with cancer (“denial”)59 | Malignant melanoma. All patients disease free at point of testing | Recurrence at 1 year | Stage, positive/ enlarged nodes, histology, Clark level, location of primary, age, sex, time from symptoms to diagnosis | Amount of adjustment required lower in patients with relapse (mean score=53 v 80, P<0.001). Adjustment score did not correlate with number of positive nodes | + | 2,3 |

| Watson (1999)7 UK |

578 (100%); 55 years | Fighting spirit, helplessness/ hopelessness, anxious preoccupation, fatalism, avoidance,48 emotional suppression | Stage I and II breast cancer | 5 years | Histopathological grade, positive lymph nodes, tumour size, operation, chemotherapy v endocrine therapy, ER status | No effect of predominant coping style or emotional suppression on event-free survival. Only helplessness/ hopelessness significant (high v low scorers) (RR=1.55, 1.07 to 2.25) but not when it was predominant coping response (1.15, 0.60 to 2.22) | +/− | 1,2,3 |

RR=relative risk; HR=hazard ratio; OR=odds ratio.

Some studies investigated both recurrence and survival and therefore appear in table 1 also.

In addition to psychosocial variables.

+=mainly significant associations found; 0=no significant associations; +/−=mixed positive and negative findings.

1=clearly defined group of patients recruited near to diagnosis, 2=adjustment for at least one confounder, 3=early assessment of coping style

Results

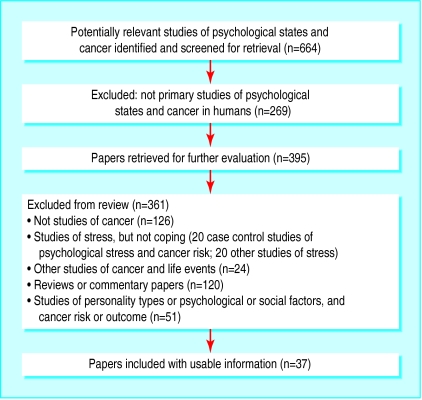

We found 26 studies that investigated the association between psychological coping and survival and 11 studies that investigated recurrence (figure). Some studies were reported in more than one paper—for example, results pertaining to different follow up periods. The most common diagnosis of patients in these studies was breast cancer, though we also found studies that investigated leukaemia, melanoma, and lung and gastrointestinal cancers, with follow up periods ranging from several months to 15 years (tables 1, 2, and 3).

Table 3.

Details of studies of survival and recurrence

| Sample size | Coping style(s) (scale used) | Site of cancer | Outcomes included in study, length of follow up (No of deaths) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reynolds1 | 847 | Expressing/suppressing emotions, wishful thinking, problem solving, positive reappraisal, avoidance, escapism, “coping repertoire” | Breast | Survival: up to 9 years (218 deaths) |

| Greer,2 5 Pettingdale,3 4 | 69 | Denial, fighting spirit, stoic acceptance, helplessness/hopelessness | Breast | Survival: 5, 10, and 15 years (34, 36, 47 deaths respectively); recurrence |

| Morris6 | 168 | Denial, fighting spirit, anxious preoccupation, stoic acceptance, helplessness/hopelessness | Breast, lymphoma | Survival: up to 5 years (20 deaths); recurrence |

| Watson7 | 578 | Fighting spirit, helplessness/hopelessness, anxious preoccupation, fatalism, avoidance,48 emotional suppression | Breast | Survival: 5 years (133 deaths); recurrence |

| Brown8 | 426 | Active, distractive, and avoidant coping; adjustment to cancer | Early stage melanoma | Survival: 2 years (60 deaths); recurrence |

| Andrykowski13 | 42 | Fighting spirit, hopelessness/helplessness, anxious preoccupation, fatalism, avoidance48 | Leukaemia | Survival: median=2.2 months (27 deaths) |

| Cody14 | 209 | Fighting spirit, helplessness, anxiety, fatalism, avoidance48 | Lung | Survival: 8 weeks (deaths not stated) |

| Dean15 | 125 | Stoic acceptance, fighting spirit, denial, hopelessness/helplessness, anxious/ depressed51 | Breast | Survival: 6-8 years (22 deaths); recurrence |

| Giraldi16 | 95 | Fighting spirit, hopelessness, anxious preoccupation, fatalism48 | Breast | Survival: 6 years (15 deaths) |

| Murphy17 | 56 | Fighting spirit, helplessness, anxiety, fatalism, avoidance48 | Leukaemia, lymphoma, aplastic anaemia | Survival: mean=82 months (18 deaths) |

| Nordin18 19 | 139 | Fighting spirit, helplessness, anxious preoccupation, anxiety, fatalism, avoidance (MAC scale)48 | Colorectal, gastric, pancreatic, and biliary cancers | Survival: ⩽12 months (56 deaths) |

| Tschuschke20 | 52 | Passive reception/resignation, distraction, cognitive structuring, social contact, compliance, fighting spirit | Leukaemia | Survival: mean survival time=2.6 years (21 deaths) |

| Cassileth21 22 | 204 +155 | Hopelessness/helplessness, amount of adjustment required to cope with diagnosis | Pancreatic, gastric, lung, colorectal cancer, glioma, melanoma, or breast | Survival:1985—group I median survival 7 months; group II median 12 months to recurrence 1988—follow up at 3-8 years; recurrence |

| Molassiotis23 | 31 | Emotion focused coping, humour, withdrawal, acceptance, hopefulness52 | Haematological malignancies | Survival: 1-2 years (20 deaths) |

| Ringdal24 25 | 253 | Hopelessness54 | Breast, gastrointestinal, prostate, lung; lymphoma | Survival: mean survival time=17 months |

| Jensen26 | 86 | Defensiveness, helplessness/hopelessness, negative affect, chronic stress, and daydreaming | Breast | Recurrence: average follow up=624 days (11 deaths) |

| Butow27 | 125 | Active, distractive, avoidant coping | Metastatic melanoma | Survival: 2 years (deaths not stated) |

| Butow28 | 99 | Active, distractive and avoidant coping; adjustment to cancer (stigma/isolation, minimisation, anger) | Metastatic breast | Survival: 2 years (62 deaths) |

| Richardson29 | 139 | Behavioural and cognitive coping, including avoidance, information seeking, problem solving, affective regulation53 | Haematological malignancies, rectal | Survival: ⩽5 years (64 deaths) |

| Achté30 | 126 | Denial, repression | Not stated | Survival: up to 3 years (35 deaths) |

| Silberfarb31 | 290 | Denial of illness | Multiple myeloma | Survival: 2 years (deaths not stated) |

| Buddeberg34 35 36 37 | 107 | Depressive coping, distrust and pessimism, “regressive tendency,” self encouragement, distraction, self revalorisation, control of feelings and withdrawal, problem solving)56 57 | Breast | Survival: 3 years; 5-6 years; 10 years |

| Derogatis38 | 35 | Anxiety, depression, hostility, guilt, psychoticism, general psychological symptom severity index (defined by author as study of coping) | Breast | Survival: long term survivors (mean=23 months) v short term survivors (mean=9 months) (13 deaths) |

| Faller39 40 | 103 | Depressive coping, active coping, hope | Lung | Survival: up to 7 years |

| Hislop41 | 133 | Coping by change, by control, by stress | Breast | Survival: 4 years (26 deaths); recurrence |

| De Boer49 | 133 | Uncertainty regarding how to cope with illness, or emotions50 | Head, neck | Survival: 6 years (57deaths); recurrence |

| Schulz55 | 268 | Pessimism, optimism | Breast, lung, head, neck, gynaecological, other | Survival: 8 months |

Assessment of validity

Thirteen studies met all three methodological criteria. Table 3 shows methodological details of each study. Table 1 shows studies of survival, and table 2 shows studies of recurrence. About a third of all studies did not adjust for potential confounding variables. Most of the studies were small; the overall median sample size was 125, and only four studies recruited more than 200 patients. There was no association between study quality (scored 1 to 3, see tables 1 and 2) and study outcome (presence versus absence of significant findings; χ2 test for trend; P=0.5). Where studies are referred to as “small” this is defined as “smaller than the median study size.”

Findings

Fighting spirit—Ten studies investigated the impact of “fighting spirit” on survival.2,3,5–7,13–20 Positive findings that linked use of this coping style to longer survival were confined to two small studies (table 1).2–5,20 Four small studies examined the association with recurrence of cancer. Three studies reported that fighting spirit was associated with a reduced risk.2–4,6,15 This finding was not confirmed by the fourth, larger study (n=578).7

Helplessness/hopelessness—Twelve studies examined hopelessness/helplessness as a predictor of reduced survival in cancer patients.2–4,6,7,13–19,21–25 Only two small studies reported that more frequent such feelings adversely affected survival.2,23 Five studies presented data on recurrence of cancer, but the findings were inconsistent.6,7,15,21,22,26 In one study, few data were presented15 and in another the outcome variable was a composite variable based on a 13 point indicator of clinical status.26 The two other studies that reported associations with recurrence were small or limited by methodological problems, or both. In particular, there was limited control of confounding.2,21,22 The recent large UK study (n=578), while of higher quality, reported mixed findings: helplessness/hopelessness predicted recurrence when those with high and low scores were compared but not when it was the predominant coping style.7

Denial or avoidance—Denial or avoidance were assessed in 15 studies of survival; 10 of these investigated avoidance1,7,8,13,14,17–19,27–29 and five investigated denial.2–4,6,15,30,31 These studies did not report any significant independent associations between the use of an avoidant style of coping and survival. There was also little evidence to suggest that denial was an important predictor of survival1,7,13,27,28: two studies reported an association between denial and survival but one presented no supporting data.30 The other small study found that the use of denial predicted death from breast cancer at 10 and 15 years.2–4 Eight studies explored the effects of denial or avoidance on recurrence of cancer.2–4,6–8,15,20,32,33 Only one of these studies (a small study carried out in patients with breast cancer) reported that denial predicted recurrence.2–4 This association was not reported in other larger studies.7,8

Stoic acceptance and fatalism—Nine studies explored the impact of acceptance and fatalism,2,6,7,13–19 and none of the four higher quality studies found that they predicted survival.7,13,15,16 The evidence regarding recurrence of cancer was similarly weak.2,6,7,15 The only study that reported a significant association presented no supporting data.15

Anxious coping/anxious preoccupation, depressive coping—Ten studies investigated the impact of an anxious or depressive coping style on survival.6,7,14–19,34–40 One small study reported that higher anxious preoccupation scores predicted shorter survival,13 and a study of 103 patients found that the use of depressive coping predicted shorter survival.39,40 Three studies presented relative risks associated with anxious preoccupation, all of which were close to 1.0.7,13,18,19 One small study (n=35) reported an association between depression and survival, though this study had methodological drawbacks with respect to patient recruitment and confounding.38 None of these psychological factors was reported to be significantly associated with recurrence of cancer.

Active or problem focused coping—Eight studies explored the effects of active or problem focused coping on survival,1,8,27–29,34–37,39–41 one of which (n=103) reported that the use of active coping was a predictor of longer survival up to seven years.39,40 The largest study (n=847) compared high, medium, and low users of this coping style and found no association with survival after they controlled for clinical and sociodemographic factors.1 Another study (n=133), which investigated a coping style labelled “coping by control,” reported no significant findings.41 Active or problem focused coping was not associated with recurrence.

Emotional factors (including suppression of emotions and emotion focused coping)—We identified six studies on survival.1,7,23,29,30,34–37 One study (n=847) met the three quality criteria and reported a positive association between expressing emotions (categorised as high, medium, or low) and longer survival (hazard ratio 0.6, 95% confidence interval 0.4 to 0.9).1 Another large good quality study examined the impact of emotional suppression on outcome but found no significant associations with either overall or event-free survival.7

Publication bias

We could not carry out standard methods of assessing publication bias such as funnel plots because there was great heterogeneity among the studies and there were only a small number of studies in each category of coping style. Studies that reported “positive” findings were smaller than those that reported non-significant findings (mean sample size 89 v 198, P=0.02, two tailed), which is indicative of publication bias.

Discussion

It is commonly believed that a person's mental attitude in response to a diagnosis of cancer affects his or her chances of survival, and the psychological coping factors that are most well known in this respect are fighting spirit and helplessness/hopelessness.42 We found little convincing evidence that either of these factors play a clinically important part in survival from or recurrence of cancer; the significant findings that do exist are confined to a few small studies. Good evidence is also lacking to support the view that “acceptance,” “fatalism,” or “denial” have an important influence on outcome.

Our review has several possible limitations. Firstly, the validity assessment focused on only three methodological criteria and other criteria are known to be important, such as the adequacy of baseline information.43 However, when we piloted the validity assessment checklist these criteria did not seem to differentiate adequately between the studies. We could have adopted a more stringent set of criteria, but this would be unlikely to alter the (already negative) conclusions of the review.

The review may also be subject to publication bias because the studies reporting “positive” findings tended to be smaller. We tried to identify unpublished studies, including theses and conference papers, but small studies with negative findings are less likely to be published in any form and thus may be more difficult to locate.44 Among the studies that we did identify, relatively few had adequately adjusted for important predictors of disease-free and overall survival, such as age and histological grade,45 and this is a possible explanation for some of the positive findings.

Overall we found little evidence that coping styles play an important part in survival from cancer. This is an important finding because there is often pressure on patients with cancer to engage in “positive thinking,” and this may add to their psychological burden.46,47 It has been suggested that clinicians need to detect coping styles such as helplessness or hopelessness and treat them vigorously.7 Our findings show that such interventions may be inappropriate, at least when they are used with the aim of increasing survival or reducing the risk of recurrence.

Conclusion

Good evidence in this subject is still scarce as there have been few large methodologically sound studies. Although the relation is biologically plausible, there is at present little scientific basis for the popular lay and clinical belief that psychological coping styles have an important influence on overall or event-free survival in patients with cancer.

Figure.

Flowchart for main search. Search terms included: (cancer$ or neoplasm$), expanded in Medline and other databases where possible and denial or coping or attitude or fighting spirit or avoidance or hope$ and (prognos$ or relapse or recurrence or survival or progression)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to those who supplied additional data, Herman Faller, Allan House, and Sue Lockwood who commented on earlier versions of the paper, and Susan Kennedy for help with redrafting.

We carried out a supplementary search in June 2002 to update the review while it was undergoing peer review: Medline 117 additional hits; PsycLit 88 additional hits; Assia 23 additional hits; Embase 113 additional hits; Cancerlit 115 additional hits; Dissertation Abstracts 88 additional hits; Healthstar no longer existed but is now part of NLM gateway and this was searched instead, 220 additional hits from Oct 2001-June 2002; CINAHL 60 additional hits from Aug 2001 to June 2002. None of these abstracts was relevant to the review and none met the inclusion criteria.

Footnotes

Funding: MP is funded by the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Executive Department of Health and is a member of the ESRC-funded Evidence Network.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Reynolds P, Hurley S, Torres M, Jackson J, Boyd P, Chen V. Use of coping strategies and breast cancer survival: results from the Black/White cancer survival study. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:940–949. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.10.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greer S, Morris T, Pettingale K. Psychological response to breast cancer: effect on outcome. Lancet. 1979;ii:785–787. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)92127-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pettingale K. Coping and cancer prognosis. J Psychosom Res. 1984;28:363–364. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(84)90066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pettingale K, Morris T, Greer S, Haybittle J. Mental attitudes to cancer: an additional prognostic factor. Lancet. 1985;i:750. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)91283-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greer S, Morris T, Pettingale K, Haybittle J. Psychological response to breast cancer and 15-year outcome. Lancet. 1990;335:49–50. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris T, Pettingale K, Haybittle J. Psychological response to cancer diagnosis and disease outcome in patients with breast cancer and lymphoma. Psychooncology. 1992;1:105–114. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watson M, Haviland J, Greer S, Davidson J, Bliss J. Influence of psychological response on survival in breast cancer: a population-based cohort study. Lancet. 1999;354:1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)11392-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown J, Butow P, Culjak G, Dunn S. Psychosocial predictors of outcome: time to relapse and survival in patients with early stage melanoma. Br J Cancer. 2000;83:1448–1453. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerits P. Life events, coping and breast cancer: state of the art. Biomed Pharmacother. 2000;54:229–233. doi: 10.1016/S0753-3322(00)80064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Angell M. Disease as a reflection of the psyche. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:1570–1572. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198506133122411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stroup D, Berlin J, Morton S, Olkin I, Williamson G, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Undertaking systematic reviews of research on effectiveness: CRD guidelines for those carrying out or commissioning reviews. York: University of York; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andrykowski M, Brady M, Henslee-Downee P. Psychosocial factors predictive of survival after allogenic bone marrow transplantation for leukemia. Psychosom Med. 1994;56:432–439. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199409000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cody M, Nichols S, Brennan C, Armes J, Wilson P, Slevin M. Psychosocial factors and lung cancer prognosis. Psychooncology. 1994;3:141. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dean C, Surtees P. Do psychological factors predict survival in breast cancer? J Psychosom Res. 1989;33:561–569. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(89)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giraldi T, Rodani M, Cartei G, Grassi L. Psychosocial factors and breast cancer: a 6-year Italian follow-up study. Psychother Psychosom. 1997;66:229–236. doi: 10.1159/000289140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphy K, Jenkins P, Whittaker J. Psychosocial morbidity and survival in adult bone marrow transplant recipients—a follow-up study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1996;18:199–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nordin K, Glimelius B. Psychological reactions in newly diagnosed gastrointestinal cancer patients. Acta Oncol. 1997;36:803–810. doi: 10.3109/02841869709001361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nordin K, Glimelius B. Reactions to gastrointestinal cancer—variation in mental adjustment and emotional well-being over time in patients with different prognoses. Psychooncology. 1998;7:413–423. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(1998090)7:5<413::AID-PON318>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tschuschke V, Hertenstein B, Arnold R, Bunjes D, Denzinger R, Kaechele H. Associations between coping and survival time of adult leukemia patients receiving allogenic bone marrow transplantation. Results of a prospective study. J Psychosom Res. 2001;50:277–285. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00202-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cassileth B, Walsh W, Lusk E. Psychosocial correlates of cancer survival: a subsequent report 3 to 8 years after cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 1988;6:1753–1759. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1988.6.11.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cassileth B, Lusk E, Miller D, Brown L, Miller C. Psychosocial correlates of survival in advanced malignant disease? N Engl J Med. 1985;312:1551–1555. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198506133122406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Molassiotis A, Van Den Akker O, Milligan D, Goldman J. Symptom distress, coping style and biological variables as predictors of survival after bone marrow transplantation. J Psychosom Res. 1997;42:275–285. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(96)00298-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ringdal G, Gotestam K, Kaasa S, Kvinnsland S, Ringdal K. Prognostic factors and survival in a heterogeneous sample of cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 1996;73:1594–1599. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ringdal G. Correlates of hopelessness in cancer patients. J Psychosoc Oncol. 1995;13:47–66. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jensen M. Psychobiological factors predicting the course of breast cancer. J Pers. 1987;55:317–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1987.tb00439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butow P, Coates A, Dunn S. Psychosocial predictors of survival in metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2256–2263. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.7.2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Butow P, Coates A, Dunn S. Psychosocial predictors of survival: metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2000;11:469–474. doi: 10.1023/a:1008396330433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richardson J, Zarnegar Z, Bisno B, Levine A. Psychosocial status at initiation of cancer treatment and survival. J Psychosom Res. 1990;34:189–201. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(90)90053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Achté K, Vuhkonen ML, Achté A. Psychological factors and prognosis in cancer. Psych Fenn 1979:19-24.

- 31.Silberfarb P, Anderson K, Rundle A, Holland J, Cooper M, McIntyre O. Mood and clinical status in patients with multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:2219–2224. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.12.2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Epping-Jordan J, Compas B, Howell D. Predictors of cancer progression in young adult men and women: avoidance, intrusive thoughts, and psychological symptoms. Health Psychol. 1994;13:539–547. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.6.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rogentine G, van Kammen D, Fox B, Docherty J, Rosenblatt J, Boyd S, et al. Psychological factors in the prognosis of malignant melanoma: a prospective study. Psychosom Med. 1979;41:647–655. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197912000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buddeberg C, Riehl Emde A, Landont R, Steiner R, Sieber M, Richter D. The significance of psychosocial factors for the course of breast cancer—results of a prospective follow-up study. Schweiz Arch Neurol Psychiatr. 1990;141:429–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buddeberg C, Wolf C, Sieber M, Riehl Emde A, Bergant A, Steiner R, et al. Coping strategies and course of disease of breast cancer patients. Results of a 3-year longitudinal study. Psychother Psychosom. 1991;55:151–157. doi: 10.1159/000288423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buddeberg C, Sieber M, Wolf C, Landolt-Ritter C, Richter D, Steiner R. Are coping strategies related to disease outcome in early breast cancer? J Psychosom Res. 1996;40:255–264. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(95)00518-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buddeberg C, Buddeberg-Fischer B, Schnyder U. Coping strategies and 10-year outcome in early breast cancer. J Psychosom Res. 1997;43:625–626. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(97)00189-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Derogatis L, Abeloff M, Melisaratos N. Psychological coping mechanisms and survival time in metastatic breast cancer. JAMA. 1979;242:1504–1508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Faller H, Bulzebruck H, Drings P, Lang H. Coping, distress, and survival among patients with lung cancer. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:756–762. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.8.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Faller H, Bulzebruck H, Schilling S, Drings P, Lang H. Beeinflussen psychologische Faktoren die Uberlebenszeit bei Krebskranken? II: Ergebnisse einer empirischen Untersuchung mit Bronchialkarzinomkranken. [Do psychological factors modify survival of cancer patients? II: Results of an empirical study with bronchial carcinoma patients] Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 1997;47:206–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hislop T, Waxler N, Coldman A, Elwood J, Khan L. The prognostic significance of psychosocial factors in women with breast cancer. J Chron Dis. 1987;40:729–735. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90110-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Edelman S, Craig A, Kidman A. Can psychotherapy increase the survival time of cancer patients? J Psychosom Res. 2000;49:149–156. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00153-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kahn H, Sempos C. Statistical methods in epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gilbody S, Song F. Publication bias and the integrity of psychiatry research. Psychol Med. 2000;30:253–258. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700001732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sainsbury JRC, Anderson TJ, Morgan DAL. Breast cancer. BMJ. 2000;321:745–750. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7263.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilkinson S, Kitzinger C. Thinking differently about thinking positive: a discursive approach to cancer patients' talk. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:797–811. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00337-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De Raeve L. Positive thinking and moral oppression in cancer care. Eur J Cancer Care. 1997;6:249–256. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.1997.00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Watson M, Greer S, Young J, Inayat Q, Burgess C, Robertson B. Development of a questionnaire measure of adjustment to cancer: the MAC scale. Psychol Med. 1988;18:203–209. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700002026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.De Boer M, Van den Borne B, Pruyn J, Ryckman R, Volovics L, Knegt P, et al. Psychosocial and physical correlates of survival and recurrence in patients with head and neck carcinoma: results of a 6-year longitudinal study. Cancer. 1998;83:2567–2579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.De Boer M, Pruyn J, van den Borne B, Knegt P, Ryckman R, Verwoerd C. Rehabilitation outcomes of long-term survivors treated for head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 1995;17:503–515. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880170608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morris T, Greer H, White P. Psychological and social adjustment to mastectomy. Cancer. 1977;40:2381–2387. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197711)40:5<2381::aid-cncr2820400555>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jalowiec A, Murphy S, Powers M. Psychometric assessment of the Jalowiec coping scale. Nurs Res. 1984;33:157–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moos R, Cronkite P, Billings A, Finney J. Health and daily living form manual. Palo Alto, CA: Social Ecology Laboratory, Stanford University Medical Center; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beck A, Weissman A, Lester D, Trexler L. The measurement of pessimism: the hopelessness scale. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1974;42:861–865. doi: 10.1037/h0037562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schulz R, Bookwala J, Knapp J, Scheier M, Williamson G. Pessimism, age, and cancer mortality. Psychol Aging. 1996;11:304–309. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.11.2.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sieber M, Buddeberg C, Wolf C. Reliabilitat und Validitat des Zurcher Fragebogens zur Krankheitsverarbeitung (ZKV-R) [Reliability and validity of the Zurich questionnaire of coping with illness] Schweiz Archiv Neurol Psychiatr. 1991;142:553–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Muthny F. Freiburger Fragebogen zur Krankheitsverarbeitung. Weinheim, Germany: Beltz; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of event scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. 1979;41:209–218. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rahe R. The pathway between subjects' recent life changes and their near-future illness reports: representative results and methodological issues. In: Dohrenwend B, B. Dohrenwend B, editors. Stressful life events: their nature and effects. New York: John Wiley; 1974. [Google Scholar]