Abstract

Objective

To examine the rates of cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia in patients with treated schizophrenia and in non-schizophrenic controls.

Design

Cohort study of outpatients using administrative data.

Setting

3 US Medicaid programmes.

Participants

Patients with schizophrenia treated with clozapine, haloperidol, risperidone, or thioridazine; a control group of patients with glaucoma; and a control group of patients with psoriasis.

Main outcome measure

Diagnosis of cardiac arrest or ventricular arrhythmia.

Results

Patients with treated schizophrenia had higher rates of cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia than controls, with rate ratios ranging from 1.7 to 3.2. Overall, thioridazine was not associated with an increased risk compared with haloperidol (rate ratio 0.9, 95% confidence interval 0.7 to 1.2). However, thioridazine showed an increased risk of events at doses ⩾600 mg (2.6, 1.0 to 6.6; P=0.049) and a linear dose-response relation (P=0.038).

Conclusions

The increased risk of cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia in patients with treated schizophrenia could be due to the disease or its treatment. Overall, the risk with thioridazine was no worse than that with haloperidol. Thioridazine may, however, have a higher risk at high doses, although this finding could be due to chance. To reduce cardiac risk, thioridazine should be prescribed at the lowest dose needed to obtain an optimal therapeutic effect.

What is already known on this topic

Thioridazine seems to prolong the electrocardiographic QT interval more than haloperidol

Although QT prolongation is used as a marker of arrhythmogenicity, it is unknown whether thioridazine is any worse than haloperidol with regard to cardiac safety

What this study adds

Patients taking antipsychotic drugs had higher risks of cardiac events than control patients with glaucoma or psoriasis

Overall, the risk of cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia was not higher with thioridazine than haloperidol

Thioridazine may carry a greater risk than haloperidol at high doses

Patients should be treated with the lowest dose of thioridazine needed to treat their symptoms

Introduction

Many antipsychotic drugs can prolong the QT interval, and many have been linked to cases of torsade de pointes.1 Although QT prolongation is commonly used to predict a drug's potential for arrhythmogenicity,2 several factors about this marker require clarification, including the best way to measure QT effects and the degree of prolongation that is important.3–5

Haloperidol and thioridazine are the most widely used typical antipsychotic drugs in the United States.6 Cross sectional data suggest that thioridazine may prolong the QT interval more than haloperidol,7 although only one experimental study has compared the QT effects of these drugs in humans.8 In that study, haloperidol 15 mg/day prolonged the Bazett-corrected interval (QTcB) an average of 4.7 ms (95% confidence interval −2.0 to 11.3) whereas thioridazine 300 mg/day prolonged the QTcB by 35.6 ms (30.5 to 40.7). The importance of this degree of prolongation is not known.

We compared the frequency of cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia associated with different antipsychotic drugs, in particular comparing thioridazine to haloperidol. Because cases of ventricular arrhythmia and cardiac arrest may go undiagnosed, we also examined deaths from all causes.

Participants and methods

Overview and study population

We conducted a cohort study of outpatients by using 1993 to 1996 data from three US Medicaid programmes. These data were used in an earlier study.9 We identified individuals with more than one prescription for oral thioridazine, haloperidol, risperidone, or clozapine plus at least two instances of a schizophrenia diagnosis.

We assumed that thioridazine, haloperidol, and risperidone prescriptions lasted 30 days and that clozapine prescriptions lasted seven days. For each prescription, patients were followed until the end of the prescription duration, appearance of an intervening prescription for the same or a different study drug, or occurrence of the study outcome, whichever came first. Prescriptions for multiple study drugs dispensed on the same day were excluded.

We identified two control groups based on a diagnosis of open angle glaucoma or psoriasis. These conditions were selected because they require periodic prescriptions and are not thought to be associated with cardiovascular outcomes.10,11 Controls were excluded if they had schizophrenia or a prescription for any study drug. We followed controls from the first diagnosis of the reference condition until the occurrence of the study outcome or the last claim, whichever came first.

Study outcomes

The primary outcome was one of the following diagnoses, as coded by the international classification of diseases, ninth revision (ICD-9): sudden death, cause unknown (798); instantaneous death (798.1); death occurring in less than 24 hours from onset of symptoms, not otherwise explained (798.2); unattended death (798.9); paroxysmal ventricular tachycardia (427.1); ventricular fibrillation and flutter (427.4); ventricular fibrillation (427.41); ventricular flutter (427.42); or cardiac arrest (427.5). This outcome measure was found in a previous Medicaid study to have a positive predictive value of 73% compared with medical records.12 Because of privacy concerns, medical records were not available in the current study.

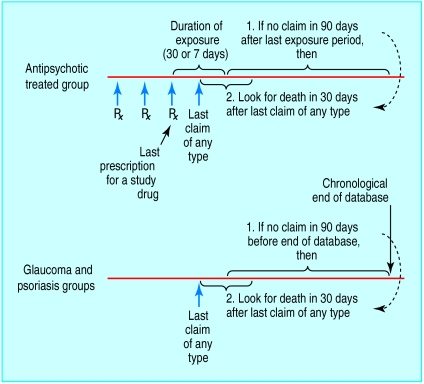

In studying all cause death, we first identified “potential deaths” among patients taking antipsychotic drugs as instances in which there were no claims after the end of the last prescription (figure). For the control groups, potential deaths were instances in which claims stopped 90 days or more before the end of the data availability period. For each potential death, we looked for a match in the 30 days after the last claim, using the social security administration death master file (SSA-DMF).13 Using this strategy, we identified 647 deaths, 623 (96%) of which were of people with a last recorded residence in the same state as the subject's Medicaid enrolment. This concordance suggested a high degree of specificity in the matching process.

Analysis

We calculated rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals using proportional hazards regression. For each outcome (cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia as a composite endpoint and death), we constructed three sets of models. The first set included patients taking antipsychotic drugs plus glaucoma patients, using glaucoma as the reference. The second set included patients taking antipsychotic drugs plus psoriasis patients, using psoriasis as the reference. The third set included only patients taking antipsychotic drugs and used haloperidol as the reference. We first adjusted for state, sex, and age (categorised as ⩽34, 35-44, 45-54, 55-64, 65-74, or ⩾75 years). We then individually examined year, drug exposures, and diagnoses as potential confounders. The candidate drugs and diagnoses are listed in the box. If adding a factor changed the rate ratio for any study drug by 10% or more, we considered that factor to be a confounder.14

Drug and disease variables examined as potential confounders

Disease variables coded as ever in past (yes/no)

Senile dementia

Heart failure

Ischaemic heart disease

Conduction disorders

Other heart disease

Cancer

HIV infection

Asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Liver disease

Obesity

Alcohol misuse

Drug variables coded as ever in past (yes/no)

Lipid lowering drugs

Systemic corticosteroids

Inhaled anti-inflammatories

Adrenergic bronchodilators

Xanthines

Nicotine replacement

Antiarrhythmic drugs

Antiretrovirals

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors

Centrally acting antihypertensive drugs

Antianginal agents

Systemic β blockers

Calcium channel blockers

Thiazide diuretics

Inotropic agents

Vasodilators

Antihypertensive combinations

Antidiabetic agents

Coagulation modifiers

Drug variables coded as current use (yes/no)

Loop diuretics

Potassium sparing diuretics

Terfenadine/astemizole

Cisapride

Antiarrhythmics

Antidepressants

Gatifloxacin/sparfloxacin

Erythromycin

Felbamate

Sumatripan

Probucol

Sotolol

Pindolol

We conducted an analysis of high risk patients, defined as those with diagnosed heart disease or a current prescription for an antiarrhythmic drug, loop diuretic, cisapride, terfenadine, amitriptyline, or pindolol. We also separately examined patients aged 65 and older and women.15

We calculated the average daily dose for each patient, for each drug, by dividing the total quantity of drug dispensed by the duration of observation. We examined the effect of dose on the primary outcome in two ways. Firstly, we performed subanalyses of those receiving <100 mg, 100-299.9 mg, 300-599.9 mg, and ⩾600 mg/day in thioridazine equivalents. We considered 2.5 mg haloperidol, 50 mg clozapine, and 0.75 mg risperidone equivalent to 100 mg thioridazine.16 Secondly, we did a subanalysis for each drug separately, looking at the rate ratio for each quarter versus the lowest quarter and calculating a P value for a linear trend using the median in each quarter as the exposure level.17 We examined confounders in the same way described above.

This study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania's committee on studies involving human beings.

Results

Table 1 presents the age and sex distributions of the study groups, as well as the number of person years, number of events, and rates of each outcome. The antipsychotic and psoriasis groups had similar ages, but the glaucoma group was older.

Table 1.

Age, sex, and crude and standardised rates of cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia and all cause mortality according to drug taken

| Clozapine (n=8330)

|

Haloperidol (n=41 295)

|

Risperidone (n=22 057)

|

Thioridazine (n=23 950)

|

Psoriasis drug (n=7541)

|

Glaucoma drug (n=21 545)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (%) of women: | 3370 (40) | 20 913 (51) | 10 621 (48) | 12 916 (54) | 4 460 (59) | 15 609 (72) |

| No (%) aged (years): | ||||||

| ⩽34 | 3131 (38) | 12 422 (30) | 7 243 (33) | 6 890 (29) | 2 806 (37) | 773 (4) |

| 35-44 | 2878 (35) | 10 338 (25) | 6 673 (30) | 5 659 (24) | 1 328 (18) | 856 (4) |

| 45-54 | 1304 (16) | 6 471 (16) | 3 827 (17) | 4 185 (17) | 1 051 (14) | 1 876 (9) |

| 55-64 | 631 (8) | 4 984 (12) | 2 171 (10) | 3 260 (14) | 1 075 (14) | 3 962 (18) |

| 65-74 | 306 (4) | 3 786 (9) | 1 412 (6) | 2 361 (10) | 705 (9) | 6 344 (29) |

| ⩾75 | 80 (1) | 3 294 (8) | 731 (3) | 1 595 (7) | 576 (8) | 7 734 (36) |

| Cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia: | ||||||

| Person years of observation | 8821 | 31 911 | 10 181 | 22 378 | 11 015 | 35 062 |

| No of cases | 19 | 135 | 51 | 86 | 20 | 119 |

| Rate per 1000 person years (95% CI) | 2.2 (1.3 to 3.4) | 4.2 (3.5 to 5.0) | 5.0 (3.7 to 6.6) | 3.8 (3.0 to 4.7) | 1.8 (1.1 to 2.8) | 3.4 (2.8 to 4.1) |

| All cause mortality: | ||||||

| Person years of observation | 8829 | 32 088 | 10 250 | 22 455 | 11 045 | 35 144 |

| No of cases | 24 | 235 | 74 | 146 | 30 | 138 |

| Rate per 1000 person years (95% CI) | 2.7 (1.7 to 4.0) | 7.3 (6.4 to 8.3) | 7.2 (5.7 to 9.1) | 6.5 (5.5 to 7.6) | 2.7 (1.8 to 3.9) | 3.9 (3.3 to 4.6) |

Table 2 gives adjusted rate ratios for each outcome. Potential confounders did not affect the rate ratios of interest in analyses restricted to patients taking antipsychotic drugs but did confound the comparisons with non-schizophrenic patients (table 2). Compared with the glaucoma and psoriasis control groups, patients taking antipsychotic drugs had rate ratios for cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia ranging from 1.7 to 3.2, and those for death ranged from 2.6 to 5.8 (table 2).

Table 2.

Adjusted rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals for cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia and all cause mortality in patients taking antipsychotic drugs with glaucoma patients, psoriasis patients, or patients taking haloperidol as the reference category

| Drug

|

Cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia

|

Death

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glaucoma*

|

Psoriasis†

|

Haloperidol‡

|

Glaucoma§

|

Psoriasis¶

|

Haloperidol‡

|

||

| Clozapine | 1.7 (1.0 to 2.9) | 1.9 (1.0 to 3.7) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.2) | 3.4 (2.1 to 5.5) | 2.6 (1.5 to 4.5) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.2) | |

| Haloperidol | 2.2 (1.7 to 3.0) | 2.4 (1.5 to 3.9) | 1.0 (reference) | 4.5 (3.6 to 5.7) | 3.2 (2.2 to 4.8) | 1.0 (reference) | |

| Risperidone | 3.1 (2.2 to 4.5) | 3.2 (1.9 to 5.4) | 1.5 (1.1 to 2.1) | 5.8 (4.3 to 8.0) | 4.1 (2.7 to 6.4) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.9) | |

| Thioridazine | 2.2 (1.6 to 3.0) | 2.4 (1.4 to 3.9) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.2) | 4.0 (3.1 to 5.2) | 2.9 (2.0 to 4.4) | 0.8 (0.7 to 1.0) | |

Adjusted for age, sex, state, heart failure, ischaemic heart disease, conduction disorder, other heart disease, ever use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, ever use of antianginal drug, ever use of calcium channel blocker, ever use of antidiabetic drug, and ever use of coagulation modifier.

Adjusted for age, sex, state, heart failure, other heart disease, cancer, ever use of adrenergic bronchodilators, ever use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, ever use of antianginal drug, ever use of calcium channel blocker, ever use of coagulation modifier, and current use of any one of the following drugs: loop diuretics, potassium sparing diuretics, terfenadine, astemizole, cisapride, antiarrhythmic drugs, antidepressants, gatifloxacin, sparfloxacin, erythromycin, felbamate, sumatriptan, probucol, sotolol, pherphenazine, or pindolol.

Adjusted for age, sex, and state. No factor affected the rate ratio by ⩾10%.

Adjusted for age, sex, state, heart failure, other heart disease, ever use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, ever use of antianginal drug, ever use of calcium channel blocker, and ever use of coagulation modifier.

Adjusted for age, sex, state, heart failure, cancer, ever use of inhaled corticosteroid, ever use of systemic corticosteroid, ever use of adrenergic bronchodilators, ever use of antiretroviral drug, ever use of calcium channel blocker, and current use of any one of the following drugs: loop diuretics, potassium sparing diuretics, terfenadine, astemizole, cisapride, antiarrhythmic drugs, antidepressants, gatifloxacin, sparfloxacin, erythromycin, felbamate, sumatriptan, probucol, sotolol, pherphenazine, or pindolol.

Risperidone was the only drug that had higher rates than haloperidol for cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia (rate ratio 1.5, 95% confidence interval 1.1 to 2.1) and for death (1.4, 1.1 to 1.9). Overall, thioridazine was not associated with an increased rate of cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia (0.9, 0.7 to 1.2) or death (0.8, 0.7 to 1.0) compared with haloperidol (table 2). Thioridazine was also not associated with a higher rate of cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia than haloperidol in the high risk population (1.1, 0.8 to 1.7), among those aged ⩾65 years (0.9, 0.6 to 1.4), or in women (1.1, 0.7 to 1.6). The dose specific rate ratio for cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia for thioridazine versus haloperidol was 0.6 (0.3 to 1.0) for <100 mg/day in thioridazine equivalents; 1.2 (0.8 to 1.9) for 100-299.9 mg/day; 1.1 (0.6 to 2.0) for 300-599.9 mg per day; and 2.6 (1.0 to 6.6; P=0.049) for ⩾600 mg/day.

Table 3 presents the dose-response analyses for cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia. Compared with thioridazine, haloperidol was used at roughly three times the equivalent dose. A dose-response relation was apparent for thioridazine (P=0.038), with patients in the highest quarter having a rate ratio of 2.5 (1.1 to 5.4) relative to those in the lowest quarter. For risperidone, the highest risk occurred with the lowest dose.

Table 3.

Rate ratios for cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia according to dose quarters of study drugs

| Quarter

|

Clozapine

|

Haloperidol

|

Risperidone

|

Thioridazine

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average daily dose (mg)*

|

Rate ratio (95% CI)†

|

Average daily dose (mg)*

|

Rate ratio (95% CI)‡

|

Average daily dose (mg)*

|

Rate ratio (95% CI)†

|

Average daily dose (mg)*

|

Rate ratio (95% CI)†§

|

||||

| 1 | <243 (<486) | 1.0 (reference) | <3.5 (<140) | 1.0 (reference) | <2.8 (<420) | 1.0 (reference) | <51 mg (<51) | 1.0 (reference) | |||

| 2 | 243-385 (486-770) | 3.4 (0.8 to 14.6) | 3.5-7.5 (140-300) | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.0) | 2.8-5.0 (420-750) | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.3) | 51-102 (51-102) | 1.6 (0.7 to 3.6) | |||

| 3 | 386-543 (772-1086) | 1.3 (0.2 to 7.1) | 7.6-15.0 (304-600) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.5) | 5.1-6.5 (765-975) | 0.4 (0.2 to 1.0) | 103-204 (103-204) | 2.2 (1.0 to 4.8) | |||

| 4 | >543 (>1086) | 0.6 (0.1 to 4.6) | >15.0 (>600) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.7) | >6.5 (>975) | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.4) | >204 (>204) | 2.5 (1.1 to 5.4) | |||

Approximate equivalent dose of thioridazine given in parentheses.

Adjusted for age, sex, state, and current use of an inotropic drug.

Adjusted for age, sex, and state.

P=0.038 for linear dose-response relation.

Discussion

We found that patients with treated schizophrenia had higher rates of cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia and of death than control patients. However, we cannot determine whether the finding is due to schizophrenia or its treatment. Our findings are consistent with those of Ray et al, who found that patients taking antipsychotic drugs had a higher rate of fatal sudden cardiac death.15

Differential effects of antipsychotic drugs

The rate ratio for cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia for risperidone compared with haloperidol was 1.5 (1.1 to 2.1). In a study comparing QT effects of different antipsychotics, risperidone 16 mg/day had an average QT effect similar to that shown by haloperidol 15 mg/day.8 We therefore did not expect that risperidone would have a greater effect than haloperidol. The fact that the highest rate was seen with the lowest risperidone dose also argues against a causal interpretation. One potential explanation is that risperidone was used preferentially, and at low dose, in the frailest patients,18 who were at highest risk. Therefore, we report this result as an incidental finding to be examined in future research.

We found that, overall, thioridazine had no higher risk of cardiac events than haloperidol. This was also true in high risk patients, in women, and in those ⩾65 years. However, our data suggest that at high doses thioridazine may have a higher risk than haloperidol and that there may be a dose-response relation for thioridazine. These findings had marginal P values and arose from multiple comparisons. However, they support the recent finding that at >100 mg/day, the rate ratio for thioridazine versus haloperidol was 1.7,15 and the finding that arrhythmia was more common in patients with thioridazine than haloperidol overdoses.19 Taken together, these findings suggest that, at high dose, thioridazine may be worse than haloperidol. Thus, to minimise the risk of arrhythmia it seems prudent to prescribe the lowest dose of thioridazine possible.

Validity of measuring QT interval

If these findings are confirmed, they would support the use of QT prolongation as a marker for a drug's arrhythmia risk. Because of the rarity of cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia, future studies of these clinical endpoints would need to include tens of thousands of subjects, as did our study. Studies of drug induced QT prolongation have traditionally been designed to examine average effects. However, an exaggerated QT response in even a few subjects may be more important than the average effect in the population. Therefore, it may be wise to design (and power) future studies to identify subsets with extreme QT responses. Further research is needed to identify high risk patients (for example, because of comorbidities, concomitant medications, or genotype) and clarify the proper role of therapeutic QT monitoring in individual patients.1

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Although privacy concerns prevented review of medical records, we used a previously validated outcome.12 We could not specifically study torsade de pointes, the arrhythmia of greatest interest, although we did study the clinically important consequences of torsade. We attempted to limit confounding by indication by excluding non-schizophrenic patients from the exposed groups and by examining a large number of clinical variables as potential confounding factors. However, confounding by indication may still have occurred, and we believe it may account for the risperidone results. Finally, because we studied patients taking oral drugs, the results may not be generalisable to patients receiving parenteral therapy.

In conclusion, our findings indicate that use of antipsychotic drugs among patients with schizophrenia is associated with increased rates of cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia and of death. Patients taking high doses of thioridazine may be at higher risk than those taking equivalent doses of haloperidol, although the P value for this finding was 0.049. To reduce the risk of arrhythmia, patients requiring thioridazine should be given the lowest dose needed to obtain an optimal therapeutic effect.

Figure.

Algorithm for identifying potential death

Footnotes

Funding: The study was funded by a research contract between the University of Pennsylvania and Pfizer (the manufacturer of ziprasidone). SH is also supported by a career development award from the US National Institute on Aging (1K23AG000987).

Competing interests: SH, WBB, JSK, and DJM have received research funding from Pfizer and Novartis. RFR and DBG are employed by Pfizer, and MFM is employed by Merck. BLS has received research funding or consulted for Pfizer, Novartis, McNeil, and Janssen. SEK has received research funding from Pfizer, Novartis, and McNeil.

References

- 1.Zarate CA, Jr, Patel J. Sudden cardiac death and antipsychotic drugs: do we know enough? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:1168–1171. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.12.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products of the European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products. Points to consider: the assessment of the potential for QT interval prolongation by non-cardiovascular medicinal products. 12-17-1997. London: Committee for Propriety Medicinal Products of EAEMP; 1997. www.emea.eu.int/pdfs/human/swp/098696en.pdf (accessed 16 October 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cavero I, Mestre M, Guillon JM, Crumb W. Drugs that prolong QT interval as an unwanted effect: assessing their likelihood of inducing hazardous cardiac dysrhythmias. Exp Opin Pharmacother. 2000;1:947–973. doi: 10.1517/14656566.1.5.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Ponti F, Poluzzi E, Montanaro N. QT-interval prolongation by non-cardiac drugs: lessons to be learned from recent experience. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;56:1–18. doi: 10.1007/s002280050714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Ponti F, Poluzzi E, Montanaro N. Organising evidence on QT prolongation and occurrence of torsades de pointes with non-antiarrhythmic drugs: a call for consensus. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;57:185–209. doi: 10.1007/s002280100290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Center for Health Statistics. Ambulatory care drug database system. www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/ahcd/ambulatory.htm (accessed 7 November 2001).

- 7.Reilly JG, Ayis SA, Ferrier IN, Jones SJ, Thomas SH. QTc-interval abnormalities and psychotropic drug therapy in psychiatric patients. Lancet. 2000;355:1048–1052. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Federal Drugs Administration Psychopharmacological Drugs Advisory Committee. Briefing document for Zeldox capsules, July 2000. www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/00/backgrd/3619b1a.pdf (accessed 7 November 2001).

- 9.Margolis D, Bilker W, Hennessy S, Vittorio C, Santanna J, Strom BL. The risk of malignancy associated with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:778–783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demailly P, Cambien F, Plouin PF, Baron P, Chevallier B. Do patients with low tension glaucoma have particular cardiovascular characteristics? Ophthalmologica. 1984;188:65–75. doi: 10.1159/000309344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stern RS, Lange R. Cardiovascular disease, cancer, and cause of death in patients with psoriasis: 10 years prospective experience in a cohort of 1,380 patients. J Invest Dermatol. 1988;91:197–201. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12464847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Staffa JA, Jones JK, Gable CB, Verspeelt JP, Amery WK. Risk of selected serious cardiac events among new users of antihistamines. Clin Ther. 1995;17:1062–1077. doi: 10.1016/0149-2918(95)80085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sesso HD, Paffenbarger RS, Lee IM. Comparison of national death index and world wide web death searches. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:107–111. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maldonado G, Greenland S. Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138:923–936. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ray WA, Meredith S, Thapa PB, Meador KG, Hall K, Murray KT. Antipsychotics and the risk of sudden cardiac death. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:1161–1167. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.12.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.British Medical Association; Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. British national formulary. London: BMA, RPS; 2001. p. 172. . (No 39). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leuraud K, Benichou J. A comparison of several methods to test for the existence of a monotonic dose-response relationship in clinical and epidemiological studies. Stat Med. 2001;20:3335–3351. doi: 10.1002/sim.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhana N, Spencer CM. Risperidone: a review of its use in the management of the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Drugs Aging. 2000;16:451–471. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200016060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buckley NA, Whyte IM, Dawson AH. Cardiotoxicity more common in thioridazine overdose than with other neuroleptics. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1995;33:199–204. doi: 10.3109/15563659509017984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]