Abstract

Objectives

To determine the strength of evidence for the effectiveness of mental health interventions for patients with three common somatic conditions (chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic back pain). To assess whether results obtained in secondary care can be extrapolated to primary care and suggest how future trials should be designed to provide more rigorous evidence.

Design

Systematic review.

Data sources

Five electronic databases, key texts, references in the articles identified, and citations from expert clinicians.

Study selection

Randomised controlled trials including participants with one of the three conditions for which no physical cause could be found. Two reviewers screened sources and independently extracted data and assessed quality.

Results

Sixty one studies were identified; 20 were classified as primary care and 41 as secondary care. For some interventions, such as brief psychodynamic interpersonal therapy, little research was identified. However, results of meta-analyses and of randomised controlled trials suggest that cognitive behaviour therapy and behaviour therapy are effective for chronic back pain and chronic fatigue syndrome and that antidepressants are effective for irritable bowel syndrome. Cognitive behaviour therapy and behaviour therapy were effective in both primary and secondary care in patients with back pain, although the evidence is more consistent and the effect size larger for secondary care. Antidepressants seem effective in irritable bowel syndrome in both settings but ineffective in chronic fatigue syndrome.

Conclusions

Treatment seems to be more effective in patients in secondary care than in primary care. This may be because secondary care patients have more severe disease, they receive a different treatment regimen, or the intervention is more closely supervised. However, conclusions of effectiveness should be considered in the light of the methodological weaknesses of the studies. Large pragmatic trials are needed of interventions delivered in primary care by appropriately trained primary care staff.

What is already known on this topic

Patients with functional somatic symptoms are common in primary care and may not receive effective mental health interventions

What this study adds

Research in secondary and primary care shows that cognitive behaviour therapy and behaviour therapy help patients with back pain and that antidepressants benefit patients with irritable bowel syndrome

Effect sizes are larger in secondary care than in primary care

Patients in secondary care with chronic fatigue syndrome may benefit from cognitive behaviour therapy

Future research should focus on large pragmatic trials with longer term follow up and economic evaluation

Introduction

As many as one in five new consultations in primary care are for somatic symptoms for which no specific cause can be found.1 Patients with such symptoms often become frequent attenders, and their management poses considerable challenges for both general practitioners and specialists.2 Although systematic reviews have shown that certain mental health interventions are effective in these patients, the treatments are not always provided.3–6 This may be partly because general practitioners question the quality of the evidence and its relevance for their patients or because the evidence of effectiveness is not widely known.7–9 Much of the research has been carried out in specialist settings, as is often the case when management is shared between primary and secondary care, and findings from specialist settings may not be applicable to primary care.

We did this study to investigate whether there is good evidence that mental health interventions are effective for patients with common somatic symptoms and whether the results of trials in secondary care can be extrapolated to primary care. We selected three common somatic conditions for which general practitioners had indicated they would welcome guidance: chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic back pain.10 In assessing the quality of published research, we also sought to identify how future trials should be designed to provide more rigorous evidence.

Method

We undertook a systematic review of randomised controlled trials, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses of mental health interventions for chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic back pain.

Search strategy

We searched PubMed, the Cochrane Library, PsycLIT, and Embase for English language papers published between 1966 and September 2001. We looked at the references cited in the identified meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and individual studies to find further studies and also searched key texts.9,11 Six liaison psychiatrists, who were known to have an interest in functional somatic complaints, were asked to cite relevant literature. Box B1 gives the full search strategy

Box 1.

Literature search strategy

- Somati* (and) treatment (or) therapy (or) rehabilitation (or) drug* (or) management (or) intervention

- Somatoform (and) treatment (or) therapy (or) rehabilitation (or) drug* (or) management (or) intervention

- Abnormal illness behaviour (and) treatment (or) therapy

- Medically (near) unexplained symptom* (and) treatment (or) therapy

- Psychophysiologic (and) treatment

- Psychogenic (and) treatment

- (Functional (near) symptom* (or) illness) and (treatment (or) therapy)

- Unaccounted medical symptoms (and) treatment (or) therapy

- Pain syndromes (and) treatment

- Chronic fatigue (or) irritable bowel (or) chronic back pain

- Treatment (or) therapy (or) rehabilitation (or) drug* (or) management (or) intervention

- Randomised controlled (or) RCTKL selected the trials to be included using the broad selection criteria (outlined above) and RR then selected relevant articles using the following criteria:

- Randomised controlled studies on chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, or chronic back pain

- Mental health interventions

- Adult study populations (>18 years)

- Studies reported in English language

- Patients with symptoms attributable to physical disease were excluded from study

Inclusion criteria

We identified published studies of cognitive behaviour, cognitive, behaviour, brief interpersonal psychodynamic, and antidepressant therapy. For analysis of the randomised controlled trials, we pooled cognitive behaviour and cognitive therapy because there is no practical distinction between them and the studies gave insufficient details about the interventions to validate any distinction. Studies that included subjects whose symptoms were attributable to physical disease were excluded.

Data extraction and assessment of study quality

One of us (RR) extracted data from the identified papers and a second reviewer checked them (KL). Discrepancies were resolved by referring to the original studies. We extracted data on the source of the patient sample; patient characteristics; the intervention and comparison treatment and who carried them out; outcomes; and study dropouts and reasons for withdrawal. Studies were defined as primary care studies if they included patients who were recruited from the community or through their primary care physician. Ten studies included a mixture of primary and secondary care patients, and these were classified as primary care studies.12–21

Both reviewers independently noted methodological details using a checklist including randomisation, blinding of those assessing outcomes, and handling of attrition in the analysis. The methodological quality of much of this literature has been previously systematically assessed using quality scales.3–5 However, the scales vary in the dimensions covered and their complexity. We therefore assessed the relevant methodological aspects individually rather than use a composite score.22

Outcome measures and analysis

For all studies, we compared the findings of research from each setting by tabulating the reported health status and functional outcomes (tables 1–3). We compared initial disease severity of patients and treatment effect sizes between settings when studies used similar interventions and the same health status measures. In the limited number of cases in which we could compare primary and secondary care patients using the same outcome measure, the severity in each study was calculated by combining patients from all treatment arms. We calculated treatment effect sizes with 95% confidence intervals from the difference in mean health status after treatment and standardised them using Cohen's d.23 We combined treatment effects using fixed effects meta-analysis when two or more studies from the same setting used the same health status measure. A random effects meta-analysis was used if there was significant heterogeneity (P<0.05) of study effect sizes.

Table 1.

Literature review of mental health interventions for chronic fatigue syndrome

| Study

|

No of participants

|

Intervention group

|

Control or comparison group

|

Outcomes*

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short term (0-6 months)

|

Medium term (>6 months)

|

||||

| Cognitive behaviour therapy† | |||||

| Patients from primary care or community: | |||||

| Ridsdale (2001)60 |

160 | Cognitive behaviour therapy | Non-directive counselling | No significant difference in fatigue, anxiety, depression, social adjustment, use of antidepressants, or consultations. No significant difference in cost effectiveness | |

| Patients from secondary care: | |||||

| Prins (2001)56 |

278 | Cognitive behaviour therapy | Support, no intervention | 14 month follow up: decrease in fatigue severity and increase in functional support | |

| Deale (1997)57 (2001)79 |

60 | Cognitive behaviour therapy | Relaxation | Increase in functional status and social adjustments, decrease in fatigue, no significant difference in depression and general health | 5 year follow up: increase in those reporting “(very) much better,” complete recovery, no relapses, and symptom improvement. No significant difference in fatigue or mental health. Only 26% patients judged completely recovered |

| Sharpe (1996)58 |

60 | Cognitive behaviour therapy | Medical care | 12 month follow up: improved functional status and coping, decrease in illness cognitions, depression improved non-significantly | |

| Lloyd (1993)59 |

90 | Cognitive behaviour therapy (with spouse) with or without immunological therapy | Placebo with or without attending clinic | No significant difference in physical capacity, functional status, or psychological morbidity | |

| Behaviour therapy | |||||

| Patients from secondary care: | |||||

| Powell (2001)67 |

148 | Behaviour therapy (graded exercise) | Medical care | 12 month follow up: increase in physical functioning, decrease in fatigue, and increased belief that chronic fatigue syndrome is related to physical deconditioning | |

| Wearden (1998)45 |

132 | Behaviour therapy (graded exercise) + selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | Exercise + placebo or review appointment + SSRI or review appointment + placebo | Exercise increased functional work capacity but no improvement in depression | |

| Fulcher (1997)66 |

66 | Behaviour therapy (graded exercise) | Relaxation and stretching | Decrease in fatigue, increase in functional capacity and general health | |

| Antidepressants‡ | |||||

| Patients from primary care or community: | |||||

| Vercoulen (1996)12 |

96 | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (therapeutic dose) | Placebo | No significant difference in depression, wellbeing, fatigue, functional status, sleep disturbances, neuropsychological functioning, social interactions, or cognition | |

| Patients from secondary care: | |||||

| Hickie (2000)44 |

90 | Monoamine oxidase inhibitors | Placebo | Increase in vigour, no significant difference in disability, fatigue, and depression | |

| Wearden (1998)45 |

132 | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors + behaviour therapy (graded exercise) | Exercise + placebo or review appointment + selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or review appointment + placebo | Serotonin reuptake inhibitors: improve depression but no improvement in fatigue or functional work capacity | |

| Natelson (1996)46 |

18 | Monoamine oxidase inhibitors | Placebo | Improvements on composite measure of symptoms, illness severity, mood, functional status no improvements in above individual measures | |

Reported changes in outcome are significant (P<0.05) unless stated otherwise.

Studies reporting the use of cognitive therapy are reported under cognitive behaviour therapy because behaviour techniques were also used in the intervention.

All antidepressants were administered at established therapeutic levels (British National Formulary, 2001) unless otherwise stated.

Table 3.

Literature review of mental health interventions for chronic back pain

| Study

|

No of participants

|

Intervention group

|

Control or comparison group

|

Outcomes*

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short term (0-6 month)

|

Medium term (>6 month)

|

||||

| Cognitive behaviour therapy/cognitive therapy | |||||

| Patients from primary care or the community: | |||||

| Moore (2000)25 |

226 | Group cognitive behaviour therapy | Usual medical care & information | Decrease in pain & disability, interference in activities, worries, and fear avoidance beliefs | 1 year follow up: decrease in worries & fear avoidance beliefs maintained |

| Linton (2000)81 |

243 | Group cognitive behaviour therapy | Pamphlet of advice or information package |

1 year follow up: no significant difference in pain, decreased healthcare use & sick leave | |

| Rose (1997)18 |

84 | 15 hours' individual therapy |

Group therapy, 30 or 60 hours | No significant difference in improvements in pain, disability, depression, control, somatic awareness/distress, & self efficacy for both duration & group/individual | |

| Newton-John (1995)17 |

44 | Group cognitive behaviour therapy | Group behaviour therapy or waiting list control | Decrease in pain intensity & depression. Increase in adaptive cognitions | |

| Bru (1994)39 |

111 | Group cognitive behaviour therapy | Behaviour therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, or waiting list control | Decrease in pain intensity in neck and low back. Improvements in low back pain show relapse at 4 month follow up | |

| Turner (1993)19 |

102 | Group cognitive behaviour therapy | Group behaviour therapy or waiting list control |

1 year follow up: decreased pain intensity, depression, & disability | |

| Turner (1988)20 |

81 | Group cognitive behaviour therapy | Group behaviour therapy or waiting list control |

Decrease in pain behaviour + physical & psychosocial dysfunction | 1 year follow up: sickness impact & pain behaviour continue to improve |

| Patients from secondary care: | |||||

| Kole-Snijders (1999)26 & Goossens (1998)27 |

148 | Group cognitive behaviour therapy | Individual behaviour therapy (with spouse), individual behaviour therapy (without spouse), or waiting list control |

Decrease in negative affect and increase in coping & overall health measure. 6 month follow up: further improvement in motor behaviour |

1 year follow up: no significant difference in negative affect, motor behaviour, coping, or costs & overall health between intervention groups |

| Strong (1998)24 |

30 | Individual cognitive behaviour therapy + usual treatment (pain control, psychiatry, occupational therapy & physiotherapy) | Usual treatment (pain control, psychiatry, occupational therapy & physiotherapy) | Increased control over pain, use of coping. Decreased helplessness, depression, disability, pain intensity (not sustained at 3 months) | |

| Bendix (1997,98, 98)32-35 |

123 | Cognitive behaviour therapy (group multidisciplinary) | Cognitive behaviour therapy (coping & behaviour therapy) or cognitive behaviour therapy (physical training + back school) |

1 year follow up: multidisciplinary group showed decrease in healthcare use, back pain, disability, and analgesia use. Increase in work-ready rate. No difference between other two groups. 5 year follow up: multidisciplinary group showed improvements in working and daily activities. |

|

| Basler (1997)36 |

94 | Cognitive behaviour therapy + standard medical treatment | Standard medical treatment | Decrease in pain, avoidance behaviour, & catastrophising. Increase in pleasurable activities + feelings, control over pain, social disability, mental performance, functional capacity. |

|

| Vlaeyen (1995)28 |

71 | Cognitive behaviour therapy (part group, part individual) | Behaviour therapy (part group, part individual) or waiting list control |

Decrease in pain behaviours, mood, cognitions (catastrophising). Improved functional status. No significant difference in depression & pain intensity | |

| Altmaier (1992)31 |

45 | Cognitive behaviour therapy + education, support, exercise (part group, part individual) | Education, support + exercise (part group, part individual) | No effect on disability, pain intensity, levels of interference of pain (including mood) & return to work | |

| Nicholas (1992)30 |

20 | Group cognitive behaviour therapy + physiotherapy | Group physiotherapy + discussion | Increase in coping & functioning, decrease in sickness impact & medication use |

|

| Nicholas (1991)29 |

58 | Group cognitive behaviour therapy +/− relaxation | Group behaviour therapy +/− relaxation or physiotherapy + discussion or physiotherapy only |

1 year follow up: no significant difference in pain intensity, functional status, cognitions, use of active coping. | |

| Turner (1982)43 |

36 | Group cognitive behaviour therapy | Group behaviour therapy or waiting list control |

Fall in pain, disability, depression | 2 year follow up: decrease in healthcare use, increase in time spent working |

| Behaviour therapy | |||||

| Patients from primary care or the community: | |||||

| Newton-John (1995)17 |

44 | Group behaviour therapy | Group cognitive behaviour therapy or waiting list control |

Fall in pain intensity & depression, increase in adaptive cognitions | |

| Bru (1994)39 |

111 | Group behaviour therapy | Group cognitive behaviour therapy or waiting list control |

Fall in pain intensity in low back pain | |

| Donaldson (1994)38 |

36 | Behaviour therapy (biofeedback) 36 participants |

Relaxation or education |

Decreased pain in behaviour therapy (biofeedback) only | |

| Turner (1993)19 |

102 | Group behaviour therapy | Group cognitive behaviour therapy or waiting list control |

1 year follow up: decrease in pain intensity, depression, disability. No difference between intervention groups | |

| Lindstrom (1992)40 |

103 | Behaviour therapy | Analgesics, some “preset” physiotherapy, rest | Return to work earlier | 1 year follow up: less time off work, fewer symptoms |

| Turner (1990)37 |

96 | Group behaviour therapy (with spouse) + group exercise | Group exercise or group behaviour therapy (with spouse), or waiting list control |

Decrease in pain behaviour and physical and psychosocial disability | 1 year follow up: no difference in improvement between intervention groups |

| Linton (1989)41 |

66 women only | Group behaviour therapy | Waiting list control | Decrease in pain, fatigue, anxiety, negative mood. Increase in sleep and activity level | |

| Turner (1988)20 |

81 | Group behaviour therapy | Group cognitive behaviour therapy | Decreased pain behaviour + physical & psychosocial dysfunction but no significant difference in pain severity | 1 year follow up: improvements in sickness impact & pain behaviour level off |

| Nouwen (1983)77 |

20 | Behaviour therapy (biofeedback) | Waiting list control | No significant effect on pain | |

| Patients from secondary care: | |||||

| Kole-Snijders (1999) & Goossens (1998)2627 |

148 | Individual behaviour therapy (with spouse) | Group cognitive behaviour therapy, individual behaviour therapy (without spouse), or waiting list control |

Compared with behaviour therapy (with or without spouse): decreased negative affect and increase in coping & overall health measure | 1 year follow up: no significant difference in negative affect, motor behaviour, or coping between intervention groups |

| Vlaeyen (1995)28 |

71 | Behaviour therapy (part group, part individual) | Cognitive behaviour therapy (part group, part individual) or waiting list control |

Decrease in pain behaviours, negative mood, and cognitions (catastrophising). Increase in functional status, no significant difference in depression & pain intensity | |

| Altmaier (1992)31 |

45 | Education, support + exercise (considered here to be behaviour therapy) (part group, part individual) | Cognitive behaviour therapy + education, support, exercise (part group, part individual) | No significant difference in improvements in disability, pain intensity, levels of interference of pain (including mood) & return to work | |

| Nicholas (1991)29 |

58 | Group behaviour therapy +/− relaxation | Group cognitive behaviour therapy +/− relaxation or physiotherapy + discussion or physiotherapy only |

Improvement in functional status, pain beliefs, and coping | 1 year follow up: no significant difference in functional status, pain beliefs, & intensity and coping |

| Philips (1987)42 |

40 | Behaviour therapy (pain management) | Waiting list control | 1 year follow up: decrease in pain avoidance behaviours, affective reaction to pain & depression. Increased control over pain. | |

| Turner (1982)43 |

36 | Group behaviour therapy | Group cognitive behaviour therapy or waiting list control |

Decrease in pain, disability, and depression. | 2 year follow up: decreased healthcare use, increase in time spent working |

| Antidepressants | |||||

| Patients from secondary care: | |||||

| Loldrup (1989)75 |

15 | Tricyclic antidepressants | Mianserin or placebo | Decrease in pain compared with placebo only (only 10 patients) | |

| Pheasant (1983)76 |

16 | Tricyclic antidepressants | Placebo | Decreased use of analgesia, no significant difference in activity level | |

All changes are significant (P<0.05) unless stated otherwise.

Results

We identified 61 randomised controlled studies12–21,24–81 and two meta-analyses: one on the effectiveness of behaviour therapy for chronic back pain, and one on the effectiveness of antidepressants for irritable bowel syndrome.3,4 One third (20) of the randomised controlled studies were defined as primary care studies (table 4). This included eight studies of patients who had been recruited solely through their primary care physician.13,17,18,21,25,40,60,68 A further eight studies included patients who were recruited in two ways within the same trial: either by their primary care physician or self referred after media publicity.12,14–16,19,20,37,41 The authors did not distinguish the source of referral when presenting their results. A further four studies recruited volunteers, but the inclusion criteria of two of these studies specified that participants must have had sick leave for their somatic symptom, and in the third study, the general practitioner was contacted to exclude organic disease.39,41,77 The conclusions are summarised in box B2.

Table 4.

Number of comparisons conducted in each treatment setting

| Studies from primary care or the community

|

Studies from secondary care

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Chronic fatigue syndrome: | ||

| Cognitive behaviour therapy*† | 1 | 4 |

| Behaviour therapy† | 0 | 3 |

| Brief dynamic psychotherapy | 0 | 0 |

| Antidepressants | 1 | 3 |

| Irritable bowel syndrome: | ||

| Cognitive behaviour therapy*† | 3 | 5 |

| Behaviour therapy† | 2 | 2 |

| Brief dynamic psychotherapy | 0 | 2 |

| Antidepressants | 1 | 11 |

| Chronic back pain | ||

| Cognitive behaviour therapy*† | 7 | 9 |

| Behaviour therapy*† | 9 | 6 |

| Brief dynamic psychotherapy | 0 | 0 |

| Antidepressants | 0 | 2 |

Cognitive therapy is included in the category cognitive behaviour therapy as we were unable to distinguish the two in the published studies.

Some studies compared cognitive behaviour therapy with behaviour therapy as well as cognitive behaviour therapy with a control and behaviour therapy with a control intervention. These studies have been included more than once.

Box 2.

Summary of research findings for effectiveness of mental health interventions for patients with somatic symptoms in primary and secondary care

Treatments evaluated in primary and secondary care

Back pain

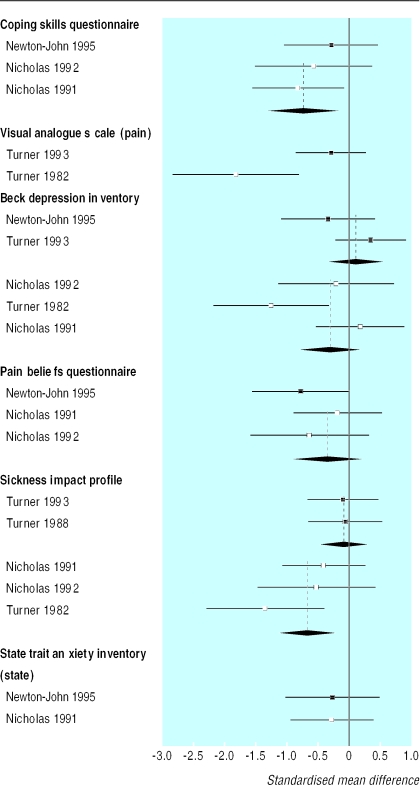

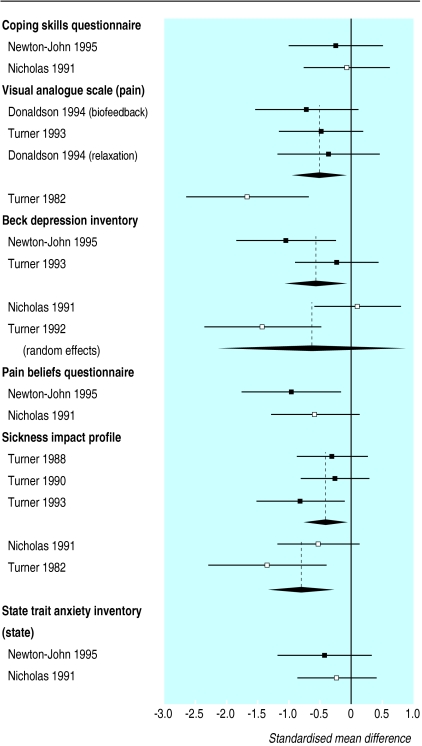

The effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy and behaviour therapy has been measured in both primary and secondary care patients. Of 16 studies of cognitive behaviour therapy for patients with back pain, seven were in primary care (891 patients) and nine in secondary care (625 patients). Patients from both settings reported sustained improvements in pain, disability, and depression.17,19,20,24–36 A meta analysis of the effectiveness of behaviour therapy found a moderate positive effect on intensity of pain and a small positive effect on behavioural outcomes in patients, regardless of setting.3 Behaviour therapy also seems to be effective in both primary and secondary care. Eight out of nine primary care studies on 659 patients and five out of six secondary care studies with a total of 398 patients reported improvements in symptoms.17,19,20,26,28,29,37–43 There was some evidence from both settings that these improvements were sustained at one year follow up.18,39,41 The initial health status of secondary care patients was poorer than that of patients in primary care (table 5) but they reported greater improvements (figs 1 and 2, table 6).

Table 5.

Health state before treatment in patients in primary care and secondary care studies (higher scores indicate greater severity for all measures except coping skills questionnaire)

| Health status measure

|

Primary care

|

Secondary care

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study

|

Mean score (95% CI)

|

Study

|

Mean score (95% CI)

|

||

| Back pain: | |||||

| Coping skills questionnaire | Newton-John17 | 50.0 (42.9 to 57.2) | Nicholas30 | 36.0 (18.5 to 53.5) | |

| Nicholas29 | 35.4 (28.3 to 42.5) | ||||

| Visual analogue scale (pain) | Donaldson38 | 27.4 (20.0 to 34.8) | Turner43 | 56.0 (47.6 to 64.3) | |

| Linton41 | 37.5* | Vlaeyen28 | 67.4 (63.5 to 71.4) | ||

| Turner19 | 54.5 (50.4 to 58.6) | ||||

| Beck depression inventory | Linton41 | 8.6* | Vlaeyen28 | 13.3* | |

| Turner19 | 10.7 (9.4 to 12.0) | Turner43 | 14.6 (12.4 to 16.9) | ||

| Newton-John17 | 12.3 (10.1 to 14.5) | Nicholas30 | 18.9 (14.7 to 23.1) | ||

| Nicholas29 | 20.2 (18.2 to 22.3) | ||||

| Pain beliefs† | Newton-John17 | 41.5 (36.5 to 46.4) | Nicholas30 | 53.6 (43.4 to 63.9) | |

| Nicholas29 | 66.2 (61.8 to 70.7) | ||||

| Sickness impact profile | Turner20 | 8.5 (6.8 to 10.2) | Turner43 | 17.4 (14.5 to 20.3) | |

| Turner19 | 12.2 (10.5 to 13.9) | Nicholas29 | 30.3 (27.9 to 32.7) | ||

| Turner 37 | 17.2 (14.4 to 19.9) | Nicholas30 | 31.5 (25.6 to 37.4) | ||

| State trait anxiety inventory (state) | Newton-John17 | 39.5 (36.2 to 42.8) | Nicholas29 | 50.8 (47.6 to 54.0) | |

| Chronic fatigue syndrome: | |||||

| Hospital anxiety and depression (anxiety) | Ridsdale61 | 9.7 (9.0 to 10.4) | Sharpe59 | 7.4 (6.3 to 8.4) | |

| Hospital anxiety and depression (depression) | Ridsdale61 | 7.6 (7.0 to 8.1) | Sharpe59 | 6.8 (5.8 to 7.7) | |

| Irritable bowel syndrome: | |||||

| Beck depression inventory | Blanchard 15‡ | 10.9 (9.3 to 12.5) | Lynch69 | 10.3* | |

| Greene14 | 11.2 (8.5 to 13.9) | ||||

| Payne13 | 12.5 (10.5 to 14.6) | ||||

| Blanchard16§ | 13.7 (10.9 to 16.6) | ||||

| State trait anxiety inventory (trait) | Blanchard ‡ | 46.9 (44.8 to 49.1) | Lynch69 | 46.2* | |

| Greene14 | 47.0 (42.7 to 51.3) | ||||

| Payne13 | 48.5 (46.3 to 50.6) | ||||

| Blanchard16§ | 48.2 (45.7 to 50.8) | ||||

| Visual analogue scale (pain) | Myren 21 | 45.2* | Tanum52 | 49.8 (44.8 to 54.8) | |

Confidence interval not available.

High score indicates stronger adherence to maladaptive beliefs.

Large study.

Small study.

Figure 1.

Standardised treatment effects and 95% confidence intervals for cognitive behaviour therapy versus control interventions in patients with back pain (negative effect sizes indicate a benefit for cognitive behaviour therapy)

Figure 2.

Standardised treatment effects and 95% confidence intervals for behaviour therapy versus control interventions in patients with back pain (negative effect sizes indicate a benefit for behaviour therapy)

Table 6.

Standardised treatment effect sizes immediately after treatment for studies comparing intervention against control for back pain. Negative effect sizes indicate a benefit of treatment over control. Effect sizes with two or more references (shown in superscript) are aggregated

| Health measure

|

Effect size (95% CI)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive behaviour therapy

|

Behaviour therapy

|

|

| Coping skills questionnaire: | ||

| Primary care | −0.29 (−1.04 to 0.47)17 | −0.26 (−1.01 to 0.49)17 |

| Secondary care | −0.73 (−1.31 to −0.15)29 30 | −0.08 (−0.76 to 0.60)29 30 |

| Pain (visual analogue scale): | ||

| Primary care | −0.29 (−0.86 to 0.28)19 | −0.52 (−0.96 to −0.09)19 38 |

| Secondary care | −1.82 (−2.84 to −0.80)43 | −1.67 (−2.65 to −0.69)43 |

| Beck depression inventory: | ||

| Primary care | 0.11 (−0.35 to 0.56)17 19 | −0.56 (−1.08 to −0.05)17 19 |

| Secondary care | −0.30 (−0.78 to 0.18)29 30 43 | −0.64 (−2.14 to 0.85)29 43 |

| Pain beliefs: | ||

| Primary care | −0.78 (−1.56 to 0.00)17 | −0.96 (−1.76 to −0.17)17 |

| Secondary care | −0.34 (−0.91 to 0.22)29 30 | −0.60 (−1.30 to 0.10)30 |

| Sickness impact profile: | ||

| Primary care | −0.08 (−0.49 to 0.33)19 20 | −0.42 (−0.76 to −0.08)19 20 37 |

| Secondary care | −0.67 (−1.14 to −0.19)19 20 43 | −0.80 (−1.33 to −0.27)29 43 |

| State trait anxiety scale: | ||

| Primary care | −0.26 (−1.01 to 0.50)17 | −0.43 (−1.19 to 0.33)17 |

| Secondary care | −0.27 (−0.93 to 0.40)29 | −0.23 (−0.87 to 0.41)29 |

Effect sizes are estimated as the difference in scores after treatment.

Chronic fatigue syndrome

Antidepressants in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome produced no sustained improvement.12,44–46

Irritable bowel syndrome

A meta-analysis of the effect of antidepressants, regardless of setting, reported a moderate improvement in symptoms.4 Antidepressants seem to be effective in both primary and secondary care: improvements in physical symptoms and depression were reported in the study that included primary care patients and 10 out of 11 studies of 444 secondary care patients.21–55 We could compare treatment effect sizes in two of these studies, and these suggest that improvement in pain relief was far greater among secondary than primary care patients (table 7).21,51 The two studies in which we could directly compare initial pain severity suggested that secondary care patients reported only slightly more severe pain than their counterparts in primary care, and patients in all these studies were similar in terms of symptom chronicity and age (table 5).21,51

Table 7.

Treatment effect sizes for chronic fatigue syndrome and irritable bowel syndrome in studies comparing intervention against control immediately after treatment and follow up. Positive effect sizes indicate a benefit of treatment over control

| Health status measure

|

Effect size (95% CI)

|

Length of follow up (months)

|

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome | ||

| Hospital anxiety and depression (anxiety): | ||

| Primary care | 0.95 (−0.5 to 2.4)60 | 6 |

| Secondary care | 0.6 (−1.1 to 2.2)58* | 5 |

| Hospital anxiety and depression (depression): | ||

| Primary care | −0.13 (−1.6 to 1.4)60 | 6 |

| Secondary care | 1.7 (−0.1 to 3.6)58* | 5 |

| Cognitive behaviour therapy for irritable bowel syndrome | ||

| Beck depression inventory: | ||

| Primary care | 3.6 (−1.0 to 8.2)13 | 3 |

| Secondary care | −3.0†63 | 3-4 |

| State trait anxiety inventory (trait): | ||

| Primary care | 3.5 (−1.6 to 8.6)13 | 3 |

| Secondary care | −7.6†63 | 3-4 |

| Antidepressants for irritable bowel syndrome | ||

| Visual analogue score (pain): | ||

| Primary care | 5.121† | After treatment |

| Secondary care | 25.9 (13.0 to 38.8)51 | After treatment |

Difference in change score (before treatment to follow up).

Confidence intervals could not be calculated because no measures of variation were reported.

Treatments with uncertain effectiveness in primary care patients

The effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome and irritable bowel syndrome has been measured in patients in both primary and secondary care but differences in treatment regimens limit the conclusions that can be drawn. Cognitive behaviour therapy has been effective in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome in secondary care, although brief cognitive behaviour therapy was ineffective.56–59 In primary care patients, there was no difference in effectiveness between brief therapy and counselling (table 7).60

Three studies of 169 primary care or community patients and five studies of 171 secondary care patients examined the effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy for irritable bowel syndrome.13,14,16,61–65 All the secondary care studies reported significant improvements with cognitive behaviour therapy in symptoms and in coping.61–65 The two smaller primary care studies reported greater symptomatic improvement with cognitive behaviour therapy than in controls, but in the largest study cognitive behaviour therapy was no better than placebo. There were insufficient data to draw conclusions about treatment effectiveness in primary care for behaviour therapy in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome (promising results were reported in secondary care) and for behaviour therapy and brief psychodynamic therapy in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. 15,45,66–74

Discussion

We found little or no research on the effectiveness of some interventions, such as brief psychodynamic interpersonal therapy. However, meta-analyses suggest that behaviour therapy is effective for chronic back pain and that antidepressants are effective for irritable bowel syndrome. Analysis of individual studies indicates that cognitive behaviour therapy and behaviour therapy for patients with back pain is more effective in patients in secondary care than those in primary care; antidepressant treatment for irritable bowel syndrome may also be more effective in secondary care. It should not, therefore, be assumed that interventions which are effective in secondary care will produce the same magnitude of effect in primary care. Instead, these findings need to be replicated independently in primary care patients.

Limitations of the evidence

For most treatments, we could draw only qualified conclusions because of methodological weaknesses in the research conducted. A major limitation of all the studies is that they evaluated the effect of interventions delivered by specialist therapists rather than primary care staff (box B3). Yet the main burden of disease occurs in primary care, and patients are unlikely to be referred to specialists because many would find it unacceptable and there is often a shortage of specialist resources.

Box 3.

Randomised trials of mental health interventions for somatic conditions: methodological shortcomings and how they should be overcome.

There was sometimes insufficient detail for us to be sure how the intervention was implemented and whether it was provided in a standardised way. Only eight studies stated that a treatment manual was used, and only two studies (by the same author) monitored adherence to the protocol.16,17,20,25,26,36,37,42 Quality checks were hardly ever mentioned; at best there was rating by an independent assessor to check that the intervention and control condition were distinct and intervention credibility checks.13,56,60,63,68 There was also a lack of data on characteristics of the patients. Age and symptom duration were usually the only data provided. Dropout rates and their causes were rarely given. 12,16,19,28,29,44,46,48,52–54,56,67,71,75

There were few studies of long term outcome. Most studies (79%) measured only immediate outcome. Longer term outcome studies would provide evidence of sustained effectiveness and reduce the possibility of non-specific effects such as those due to therapist attention or patient expectations.82 Cost effectiveness is likely to be an important motivator for changing practice, but only one study examined this.83

Patients with the conditions we studied characteristically have symptoms for many years, and such patients are likely to be frequent attenders in primary care. If, as shown for patients with other conditions, the effect of cognitive behaviour therapy continues to improve with time, it could be a highly cost effective intervention.84

Another methodological shortcoming was that studies were commonly not powerful enough to detect clinically important differences. Sample sizes were often less than 20 patients.14,30,46,50,64,68,75,76,77,80 In addition, many different outcome measures were used, which limited the number of comparisons that could be made between settings. Finally, the studies commonly had problems of internal validity—for example, the absence of strict randomisation and of blind assessment of observer rated outcomes.18,28–35,39,40,43,50,52,53,55,59,61–63,70,71,75,73,74,78

Explanations for findings

We identified four factors that may contribute to the greater improvements seen in secondary care than primary care. The first factor relates to differences between patients in the two settings. Patients in secondary care were more severely ill than their primary care counterparts (for cognitive behaviour therapy and behaviour therapy in back pain). Other unaccounted patient differences may explain the greater improvement in secondary care than primary care for patients with irritable bowel syndrome taking antidepressants. The second factor concerns differences in the treatment regimen. In the two studies of antidepressants in irritable bowel syndrome for which we could compare treatment effect sizes, the minimum therapeutic dose was used in the primary care study, whereas a dose exceeding the recommended maximum dose was used in the secondary care study.46,50 Similarly, primary care patients with chronic fatigue syndrome received just four hours of cognitive behaviour therapy whereas secondary care patients received 16 hours of treatment.58,60 The third factor concerns differences in treatment provision: for cognitive behaviour therapy in irritable bowel syndrome, studies that reported an improvement used fewer therapists, most of whom were supervised by doctors, than studies that found no effect. The final factor is concerned with differences in study design. In the studies of behaviour therapy for back pain, the control group in the secondary care setting was assigned to the waiting list, whereas in the primary care study they were provided with an educational package that could be regarded as an active treatment.38,43

Implications

Pragmatic studies of the effectiveness of psychological interventions in primary care and on unselected patients are needed to provide a basis for decisions about healthcare provision.85 Studies should identify which elements of an intervention require specialist training and which require specialist intervention. They should also measure the effectiveness of interventions carried out by primary care staff after a realistic amount of training and with the aid of standard manuals for patients and practitioners.86

The standards of reporting of trials need to be improved and harmonised to ensure that sufficient information is provided. The revised CONSORT criteria provide general guidance on trial reporting but more detailed directions are required when describing complex mental health interventions (box B4).87 As well as precise details of the intervention, baseline clinical data and data about participants deemed ineligible should be provided to inform decisions about the extrapolation of the findings to other people with the condition.

Box 4.

Checklist of items to include when reporting randomised trials of mental health interventions for somatic conditions

- How, when, and by whom they are administered (including the nature and level of training of therapist, and details of the terms used to describe the intervention to the patient)

- Provision of treatment manual (including frequency, timing, content of interventions)

- Description of quality checks (such as adherence to protocol, independent assessors of quality of intervention)

- Additional resources required (including equipment, space, support staff)

- Also give clear information on

- Characteristics of eligible v ineligible patients, recruited v not recruited patients, and those who completed study v dropouts

- Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics (including age, sex, comorbidity, baseline severity, duration, illness attributions by patient (these may be difficult to specify but are useful, particularly in developing the intervention)

- Reasons for dropout

Trials of mental health interventions should measure cost effectiveness and long term outcomes. Although outcomes and illness presentations are multifaceted and often difficult to encapsulate in one or two rating scales, this does not negate the need to rationalise the use of outcome instruments. Where possible, well tested instruments should be used and a primary outcome measure salient to both patients and clinicians should be selected. The use of both generic instruments, such as the SF-36, and of disease and symptom specific instruments should be considered.88 Trials of effectiveness should be accompanied by qualitative research on the health beliefs and attitudes of participants and non-participants. This will enable interventions to be tailored to improve recruitment and dropout rates.

Study designs should include an appropriate randomisation method, blind assessment of outcomes, and consistent handling of dropouts from each group. Whenever possible, the only difference in care between study groups should be the intervention being studied.

Conclusion

Research from both primary and secondary care suggests that that cognitive behaviour therapy and behaviour therapy may help patients with back pain and that patients with irritable bowel syndrome may improve with antidepressants but effect sizes tend to be larger in secondary care. Thus, it cannot be assumed that results from secondary care can be extrapolated to primary care. The quality and amount of evidence on mental health interventions for back pain, chronic fatigue syndrome, and irritable bowel syndrome is sometimes poor.

Table 2.

Literature review of mental health interventions for irritable bowel syndrome

| Study

|

No of participants

|

Intervention group

|

Control or comparison group

|

Outcomes*

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short term (0-6 months)

|

Medium term (>6months)

|

||||

| Cognitive behaviour therapy/cognitive therapy | |||||

| Patients from primary care or the community: | |||||

| Payne (1995)13 |

34 | Cognitive behaviour therapy | Self help, symptom monitoring | Decrease in pain, tenderness, & diarrhoea. Delayed decrease in depression & anxiety at 3 months | |

| Greene (1994)14 |

20 | Cognitive behaviour therapy | Symptom monitoring | Improvement in composite score | |

| Blanchard (1992)16 |

115 | Cognitive behaviour therapy | Attention placebo, symptom monitoring | Attention placebo: No significant difference in composite symptom score, trait anxiety, & depression Symptom monitoring: no improvement |

|

| Patients from secondary care: | |||||

| Van Dulmen (1996)61 |

47 | Cognitive behaviour therapy | Waiting list control group | Fall in duration & severity of pain, avoidance behaviours, increase in coping, no significant difference in psychological well being | 2 year follow up: Decrease in duration of pain & severity and avoidance behaviours |

| Rumsey (1991)62 |

45 | Cognitive behaviour therapy | Standard medical treatment | Decreased anxiety & depression | |

| Lynch (1989)63 |

27 | Cognitive behaviour therapy | Waiting list control group | Decrease in composite symptom score & depression, decrease in individual symptom: discomfort & constipation | |

| Neff (1987)64 |

19 | Cognitive behaviour therapy | Symptom monitoring | Fall in composite symptom score and in flatulence | |

| Bennett (1985)65 |

33 | Cognitive behaviour therapy | Tricyclic antidepressants, antianxiety drugs, laxative | Decrease in anxiety, pain, discomfort, motions, & abnormal motions | |

| Behaviour therapy | |||||

| Patients from primary care or the community: | |||||

| Keefer (2001)68 |

16 | Behaviour therapy | Symptom monitoring | Decrease in composite symptom score | |

| Blanchard (1993)15 |

23 | Behaviour therapy | Symptom monitoring | Decrease in composite symptom score and abdominal pain | |

| Patients from secondary care: | |||||

| Shaw (1991)69 |

35 | Behaviour therapy | Antispasmodic drugs | Decrease in frequency & severity of pain | |

| Corney (1990)70 |

42 | Behaviour therapy | Standard medical treatment | No significant difference in gastrointestinal symptoms & psychological outcomes | |

| Antidepressants | |||||

| Patients from primary care or the community: | |||||

| Myren (1984)47 |

428 | Tricyclic antidepressants | Placebo | Decrease in abdominal pain, acid, nausea & depression | |

| Patients from secondary care: | |||||

| Rajagopalan (1998)49 |

40 | Tricyclic antidepressants | Placebo | Decrease in pain, increase in global well- being and satisfaction with bowel movements | |

| Mertz (1998)50 |

7 | Tricyclic antidepressants (subtherapeutic dose) | Placebo | Decrease in severe gastrointestinal symptoms, no improvements to sensory feelings of fullness, discomfort or pain (under laboratory conditions) | |

| Tanum (1996)51 |

49 | Mianserin | Placebo | Decrease in pain, abdominal distress, & functional disability | |

| Vij (1991)48 | 50 | Tricyclic antidepressants |

Placebo | Decrease in pain, constipation, incomplete bowel evacuation, & diarrhoea | |

| Alevizos (1989)52 |

40 | Tricyclic antidepressants |

Placebo | Non-significant improvements in mood, retardation, & cognitive function | |

| Greenbaum (1987)53 |

41 | Tricyclic antidepressants | Placebo or atropine | Decrease in stool frequency, diarrhoea, pain, slow rectal contractions, & depression in diarrhoea-prone patients | |

| Tripathi (1983)55 |

50 | Tricyclic antidepressants (subtherapeutic dose) | Placebo | Increase in gastrointestinal improvement | |

| Myren (1982)47 |

61 | Tricyclic antidepressants | Placebo | Decrease in vomiting, sleeplessness, mucus in stools, & depression. No improvement for tiredness, anxiety, nausea, belching, headache, & composite improvement measure | |

| Lancaster-Smith (1982)78 |

48 | Combined anxiolytic/tricyclic antidepressants + bran | Placebo + bran | Decrease in abdominal pain & diarrhoea. No improvement: constipation or sensation of distension | |

| Steinhart (1981)80 |

14 | Tricyclic antidepressants (subtherapeutic dose) | Placebo | No difference in composite symptom score | |

| Heffner (1978)54 |

44 | Tricyclic antidepressants | Placebo | Decrease in bowel movement irregularities & interference with daily life. No significant difference in depression, pain/discomfort | |

| Brief psychodynamic interpersonal therapy | |||||

| Patients from secondary care: | |||||

| Guthrie (1993) & (1991)7172 |

102 | Brief psychodynamic interpersonal therapy | Supportive listening + laxative + antispasmodic drug | Decrease in abdominal pain & diarrhoea | 1 year follow up: Decrease in depression, psychiatric status & symptoms in women only (non-significant falls for men) |

| Svedlund (1985) & (1983)7374 |

101 | Brief psychodynamic interpersonal therapy + antispasmodics | Antispasmodic drug | 1 year follow up: Decrease in pain and dysfunction 15 month follow up: Decrease in gastrointestinal symptoms composite score |

|

All changes are significant (P<0.05) unless stated otherwise.

Acknowledgments

This study is part of a research programme examining the methods of group decision making for developing clinical guidelines. This research programme is overseen by a steering committee comprising three of the authors (A Haines, NB, and TS) and T Marteau and S Carter.

Footnotes

Funding: RR and KEL are funded by the Medical Research Council.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Bridges KW, Goldberg DP. Somatic presentation of DSM-III psychiatric disorders in primary care. J Psychosom Res. 1985;29:563–569. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jyvasjarvi S, Joukamaa M, Vaisanen E, Larivaara P, Kivela S, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi S. Somatising frequent attenders in primary health care. Psychosom Res. 2001;50(4):185–192. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Van Tulder M, Ostelo R, Vlaeyen J, Linton S, Morley S, Assendelf W. Behavioural treatment for chronic low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2):CD002014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Jackson J, O'Malley P, Tomkins G, Lalden E, Santoro J, Kroenke K. Treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders with antidepressants: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2000;108:65–72. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00299-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whiting P, Bagnall A-M, Sowden A, Cornell J, Mulrow C, Ramirez G. Interventions for the treatment and management of chronic fatigue syndrome. JAMA. 2001;286:1360–1368. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.11.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raine R, Lewis L, Sensky T, Hutchings A, Hirsch S, Black N. Patient determinants of mental health interventions in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50:620–625. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haines A, Jones R. Implementing the findings of research. BMJ. 1994;308:1488–1492. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6942.1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitford DL, Jelley D, Gandy S, Southern A, van Zwanenberg T. Making research relevant to the primary health care team. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50:573. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Black N. Evidence based policy: proceed with care. BMJ. 2001;323:275–279. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7307.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Health. Treatment choice in psychological therapies and counselling: evidence based clinical practice guideline. London: Department of Health; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayou R, Bass C, Sharpe M. Treatment of somatic symptoms. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vercoulen J, Swanink C, Zitman F, Vreden S, Hoofs M, Fennis J, et al. Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of fluoxetine in chronic fatigue syndrome. Lancet. 1996;347:858–861. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91345-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Payne A, Blanchard E. A controlled comparison of cognitive therapy and self-help support groups in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:779–786. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.5.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greene B, Blanchard E. Cognitive therapy for irritable bowel syndrome. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:576–582. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.3.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blanchard E, Green B, Scharff L, Schwartz-McMorris S. Relaxation training as a treatment for irritable bowel syndrome. Biofeedback Self Regul. 1993;18(3):125–132. doi: 10.1007/BF00999789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blanchard E, Schwarz, Suls J, Gerardi M, Scharff L, Greene B, et al. Two controlled evaluations of multi-component psychological treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Behav Res Ther. 1992;30:175–189. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(92)90141-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newton-John T, Spence S, Schotte D. Cognitive-behavioural therapy versus EMG biofeedback in the treatment of chronic low back pain. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33(6):691–697. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00008-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rose M, Reilly J, Pennie B, Bowen-Jones K, Stanley I, Slade P. Chronic low back pain rehabilitation programs. Spine. 1997;22:2246–2253. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199710010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turner J, Jensen M. Efficacy of cognitive therapy for chronic low back pain. Pain. 1993;52:169–177. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90128-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turner J, Clancy S. Comparison of operant behavioral and cognitive-behavioral group treatment for chronic low back pain. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:261–266. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myren J, Lovland B, Larssen S-E, Larsen S. A double-blind study of the effect of trimipramine in patients with the irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1984;19:835–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Juni P, Altman DG, Egger M. Assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ. 2001;323:42–46. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7303.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deeks J, Altman D, Bradburn M. Statistical methods for examining heterogeneity and combining results from several studies in meta-analysis. In: Egger M, Smith GD, Altman DG, editors. Systematic reviews in health care: meta-analysis in context. 2nd ed. London: BMJ Books; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strong J. Incorporating cognitive-behavioral therapy with occupational therapy: A comparative study with patients with low back pain. J Occup Rehabil. 1998;8:61–71. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore J, Von Korff M, Cherkin D, Saunders K, Lorig K. A randomized trial of a cognitive-behavioral program for enhancing back pain self care in a primary care setting. Pain. 2000;88:145–153. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00314-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kole-Snijders A, Vlaeyen J, Goossens M, Rutten-van Molken M, Heuts P, Breukelen G. Chronic low-back pain: what does cognitive coping skills training add to operant behavioral treatment? Results of a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:931–944. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goossens M, Rutten-van Molken M, Kole-Snijiders A, Vlaeyen J, Breukelen G, Leidl R. Health economic assessment of behavioural rehabilitation in chronic low back pain: a randomised clinical trial. Health Econ. 1998;7:39–51. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1050(199802)7:1<39::aid-hec323>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vlaeyen J, Haazen I, Schuerman J, Kole-Snijders A, van Eek H. Behavioural rehabilitation of chronic low back pain: comparison of an operant treatment, an operant-cognitive treatment and an operant-respondent treatment. Br J Clin Psychol. 1995;34:95–118. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1995.tb01443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicholas M, Wilson P, Goyen J. Operant-behavioural and cognitive-behavioural treatment for chronic low back pain. Behav Res Theapy. 1991;29:225–238. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(91)90112-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nicholas M, Wilson P, Goyen J. Comparison of cognitive-behavioral group treatment and an alternative non-psychological treatment for chronic low back pain. Pain. 1992;48:339–347. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90082-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Altmaier E, Lehmann T, Russell D, Weinstein J, Kao C. The effectiveness of psychological interventions for the rehabilitation of low back pain: a randomised controlled trial evaluation. Pain. 1992;49:329–335. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90240-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bendix A, Bendix T, Vægter, Lund C, Frolund L, Holm L. Multidisciplinary intensive treatment for chronic low back pain: a randomized prospective study. Cleve Clin J Med. 1996;63:62. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.63.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bendix A, Bendix T, Lund C, Kirbak S, Ostenfeld S. Comparison of three intensive programs for chronic back pain patients: a prospective, randomized, observer-blinded study with one-year follow-up. Scand J Rehab Med. 1997;29:81–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bendix A, Bendix T, Hæstrup C, Busch E. A prospective, randomized 5-year follow-up study of functional restoration in chronic low back pain patients. Eur Spine J. 1998;7:111–119. doi: 10.1007/s005860050040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bendix A, Bendix T, Labriola M, Boekgaard P. Functional restoration for chronic low back pain. Spine. 1998;23:717–725. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199803150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Basler H-D, Jakle C, Kroner-Herwig B. Incorporation of cognitive-behavioural treatment into the medical care of chronic low back patients: a controlled randomized study in German pain treatment centres. Patient Educ Counselling. 1997;31:113–124. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(97)00996-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turner J, Clancy S, McQuade J, Cardenas D. Effectiveness of behavioral therapy for chronic low back pain: A component analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1990;58:573–579. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.5.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Donaldson S, Romney D, Donaldson M, Skubick D. Randomized study of the application of single motor unit biofeedback training to chronic low back pain. J Occup Rehab. 1994;4:23–27. doi: 10.1007/BF02109994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bru E, Mykletun R, Berge W, Svebak S. Effects of different psychological interventions on neck, shoulder and low back pain in female hospital staff. Psychology and Health. 1994;9:371–382. doi: 10.1080/08870449408407495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lindstrom I, Ohlund C, Eek C, Wallin L, Peterson L-E, Fordyce W, et al. The effect of graded activity on patients with subacute low back pain: a randomised prospective clinical study with an operant-conditioning behavioral approach. Physical Therapy. 1992;72:279–290. doi: 10.1093/ptj/72.4.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Linton S, Bradley L, Jenson I, Spangfort E, Sundell L. The secondary prevention of low back pain: a controlled study with follow-up. Pain. 1989;36:197–207. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Philips H. The effects of behavioural treatment on chronic pain. Behav Res Ther. 1987;25:365–377. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(87)90014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Turner J. Comparison of group progressive-relaxation training and cognitive-behavioral group therapy for chronic low back pain. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1982;50:757–765. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.5.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hickie I, Wilson A, Wright M, Bennett B, Wakefield D, Lloyd A. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of moclobemide in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:643–648. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v61n0909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wearden A, Morriss R, Mullis P, Strickland D, Pearson D, Appleby L, et al. Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled treatment trial of fluoxtine and graded exercise for chronic fatigue syndrome. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:485–490. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.6.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Natelson BCJ, Pareja J, Policastro T, Findley T. Randomized, double blind, controlled placebo-phase trial of low dose phenelzine in the chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychopharmacology. 1996;124:226–230. doi: 10.1007/BF02246661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Myren J, Groth H, Larssen S-E, Larsen S. The effect of trimipramine in patients with the irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1982;17:871–875. doi: 10.3109/00365528209181108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vji J, Jiloha R, Kumar N, Madhu S, Malika V, Anand B. Effect of antidepressant drug (Doxepin) on irritable bowel syndrome patients. Indian J Psychiatry. 1991;33:243–246. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rajagopalan M, Kurian G, John J. Symptom relief with amitriptyline in the irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:738–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1998.tb00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mertz H, Fass R, Kodner A, Yan-Go F, Fullerton S, Mayer E. Effect of amitryptiline on symptoms, sleep and visceral perception in patients with functional dyspepsia, Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:160–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tanum L, Malt U. A new pharmacologic treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorder: a double blind placebo controlled study with mianserin. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:318–325. doi: 10.3109/00365529609006404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alevizos B, Christodoulou C, Ioannidis A, Voulgari A, Mantidis A, Spiliadis C. The efficacy of amineptine in the treatment of depressive patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1989;12:S66–S76. doi: 10.1097/00002826-198912002-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Greenbaum D, Mayle J, Vanegeren L, Jerome J, Mayor J, Greenbaum R, et al. Effects of desipramine on irritable bowel syndrome compared with atropine and placebo. Digest Dis Sci. 1987;32:257–266. doi: 10.1007/BF01297051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heffner J, Wilder R, Wilson D. Irritable colon and depression. Psychosomatics. 1978;19:540–547. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(78)70930-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tripathi B, Misra N, Gupta A. Evaluation of tricyclic compound (trimipramine) vis-a-vis placebo in irritable bowel syndrome (double blind randomised study) J Assoc Physicians India. 1983;31:201–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Prins J, Bleijenberg G, Bazelmans E, Elving L, de Boo T, Severns J, et al. Cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome: a multi-centre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;357:841–847. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04198-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Deale A, Chalder T, Marks I, Wessely S. Cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:408–414. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sharpe M, Hawton K, Simkin S, Surawy C, Hackmann A, Klimes I, et al. Cognitive behaviour therapy for the chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1996;312:22–26. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7022.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lloyd A, Hickie I, Brockman A, Hickie C, Wilson A, Dwyer J, et al. Immunologic and psychologic therapy for patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: a double blind, placebo controlled trial. Am J Med. 1993;94:197–203. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90183-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ridsdale L, Godfrey E, Chalder T, Seed P, King M, Wallace T, et al. Chronic fatigue in general practice: is counselling as good as cognitive behaviour therapy? A UK randomised trial. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51:19–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Van Dulmen A, Fennis J, Blenijenberg G. Cognitive-behavioural group therapy for irritable bowel syndrome: effects and long term follow up. Psychosom Med. 1996;58:508–514. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199609000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rumsey N. Group stress management programmes v pharmacological treatment in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. In: Heaton K, Goeting N, editors. Towards confident management of irritable bowel syndrome: current approaches. London: Duphar Medical Relations; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lynch P, Zamble E. A controlled behavioral treatment study of irritable bowel syndrome. Behav Ther. 1989;20:509–523. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Neff D, Blanchard E. A multi-component treatment for irritable bowel syndrome. Behav Ther. 1987;18:70–83. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bennett P, Wilkinson S. A comparison of psychological and medical treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Br J Clin Psychol. 1985;24:215–216. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1985.tb01340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fulcher K, White P. Randomised controlled trial of graded exercise in patients with the chronic fatigue syndrome. BMJ. 1997;314:1647–1652. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7095.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Powell PBR, Nye F, Edwards R. Randomised controlled trial of patient education to encourage graded exercise in chronic fatigue syndrome. BMJ. 2001;322:387–390. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7283.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Keefer L, Blanchard E. The effects of relaxation response meditation on the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome: results of a controlled treatment study. Behav Res Ther. 2001;39:801–811. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00078-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shaw G, Srivastava E, Saldier M, Swann P, James J, Rhodes J. Stress management for irritable bowel syndrome: a controlled trial. Digestion. 1991;50:36–42. doi: 10.1159/000200738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Corney R, Stanton R, Newell R, Clare A, Fairclough P. Behavioural psychotherapy in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 1990;35:461–469. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(91)90041-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Guthrie E, Creed F, Dawson D, Tomenson B. A randomised controlled trial of psychotherapy in patients with refractory irritable bowel syndrome. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;163:315–321. doi: 10.1192/bjp.163.3.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guthrie E, Creed F, Dawson D, Tomenson B. A controlled trial of psychological treatment for the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:450–457. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90215-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Svedlund J, Sjodin I, Ottosson J-O, Dotevall G. Controlled study of psychotherapy in irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet. 1983;ii:589–592. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)90678-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Svedlund J, Sjodin I. A psychosomatic approach to treatment in the irritable bowel syndrome and peptic ulcer disease with aspects of the design of clinical trials. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1985;20 (suppl 109):147–151. doi: 10.3109/00365528509103950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Loldrup D, Langemark M, Hansen H, Olesen J, Bech P. Clomipramine and mianserin in chronic idiopathic pain syndrome: a placebo controlled study. Psychopharmacology. 1989;99:1–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00634443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pheasant H, Bursk A, Goldfarb J, Azen S, Weiss J, Borelli L. Amitriptyline and chronic low-back pain: a randomized double-blind crossover study. Spine. 1983;8:552–557. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198307000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nouwen A. EMG biofeedback used to reduce standing levels of paraspinal muscle tension in chronic low back pain. Pain. 1983;17:353–360. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lancaster-Smith M, Pinto P, Anderson J, Schiff A. Influence of drug treatment on the irritable bowel syndrome and its interaction with psychoneurotic morbidity. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1982;66:33–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1982.tb00912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Deale A, Husain K, Chalder T, Wessely S. Long term outcome of cognitive behavior therapy versus relaxation therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome: a five year follow up study. Am J Psych. 2001;158:2038–2042. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Steinhart M, Wong P, Zarr M. Therapeutic usefulness of amitriptyline in spastic colon syndrome. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1981;11:45–57. doi: 10.2190/wfhg-gr7t-79d6-uqvd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Linton S, Andersson T. Can chronic disability be prevented? A randomized trial of a cognitive-behaviour intervention and two forms of information for patients with spinal pain. Spine. 2000;25:2825–2831. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200011010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chilvers C, Dewey M, Fielding K, Gretton V, Miller P, Palmer B, et al. Antidepressant drugs and generic counselling for treatment of major depression in primary care: randomised trial with patient preference arms. BMJ. 2001;322:772–775. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7289.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chisholm D, Godfrey E, Ridsdale L, Chalder T, King M, Seed P, et al. Chronic fatigue in general practice: economic evaluation of counselling versus cognitive behaviour therapy. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51:15–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.De Rubeis R, Crits-Christoph P. Empirically supported individual and group psychological treatments for adult mental disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:37–52. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shwartz D, Lellouch J. Explanatory and pragmatic attitudes in therapeutic trials. J Chron Dis. 1976;20:637–648. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(67)90041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Evans K, Tryer P, Catalan J, Schmidt U, Davidson K, Dent J, et al. Manual-assisted cognitive-behaviour therapy (MACT): a randomised controlled trial of a brief intervention with bibliotherapy in the treatment of recurrent deliberate self-harm. Psychol Med. 1999;29:19–25. doi: 10.1017/s003329179800765x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG.for the CONSORT group. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of parallel-group randomised trials Lancet 20013571191–1194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ware J, Sherbourne C. The MOS 36-item short form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]