The most recent reports of the Joint National Committee (JNC VI) and the World Health Organization recommend beta-blockers and diuretics as first-line therapy for uncomplicated essential hypertension (1, 2). Similar recommendations have been issued over the past few years by many authoritative sources and influential journals. These recommendations were supposedly based on multiple prospective randomized trials attesting that only beta-blockers and diuretics, both in monotherapy and in combination, reduced morbidity and mortality in hypertension.

Ever since the Veterans Administration study in the 1970s (3), multiple and prospective randomized trials have documented that diuretic-based therapy reduces the risk of stroke and, to a lesser extent, of heart attacks and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. However, the data are much less convincing for beta-blockers (4). In fact, no trial has shown that lowering blood pressure with a beta-blocker reduces the risk of a heart attack or cardiovascular event in patients with essential hypertension compared with placebo. In contrast, several prospective studies are now available showing that blood pressure reduction with calcium antagonists diminishes cardiovascular morbidity and mortality and, at least in meta-analysis, all-cause mortality. Moreover, recent data showing that the long-term use of diuretics increases the risk of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) threw a shadow on the bright picture of diuretics as reducers of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in hypertension (5).

Clearly, not all patients with essential hypertension are ideal candidates for long-term exposure to diuretic therapy. In the following, I present some caveats for the sweeping recommendations to use beta-blockers and diuretics as “preferred” antihypertensive therapy in the majority of patients.

BETA-BLOCKERS

Morbidity and mortality studies

It is somewhat ironic that after 3 decades of using betablockers for hypertension, no study has shown that their monotherapeutic use has reduced morbidity or mortality in elderly hypertensive patients compared with placebo.

In the British Medical Research Council (MRC) study in the elderly, beta-blocker monotherapy was not only ineffective but, interestingly enough, whenever a beta-blocker was added to diuretics, the benefits of the antihypertensive therapy distinctly diminished (6, 7). Thus, patients who received the combination of beta-blockers and diuretics fared consistently worse than those on diuretics alone, but they did somewhat better than those on beta-blockers alone (7).

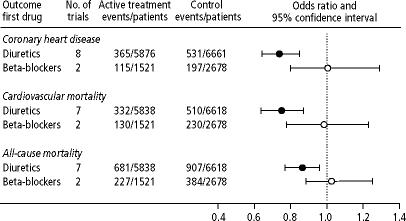

In a recent meta-analysis, we documented that although blood pressure was lowered significantly by beta-blockers, these drugs were ineffective in preventing coronary heart disease and cardiovascular and all-cause mortality (odds ratio, 1.01, 0.98, and 1.05, respectively) (Figure 1) (4). Our study showed that diuretic therapy was superior to beta-blockers with regard to all endpoints (heart attacks, fatal and nonfatal strokes, cardiovascular events, and cardiovascular and all-cause mortality) (4). We defined elderly as patients >60 years, and the analysis was based on all randomized studies that lasted ≥1 year; used a diuretic, a beta-blocker, or both as first-line therapy; and reported morbidity and mortality. Ten trials involving a total of 16,164 elderly patients fit these criteria. There was a distinct difference in the antihypertensive efficacy between the 2 therapeutic strategies: whereas hypertension was controlled in 66% of patients assigned to diuretics monotherapy, it was controlled in less than one third of patients on beta-blocker monotherapy. Despite this meager blood pressure control with beta-blocker monotherapy, the dropout rate was twice as high in the beta-blocker group compared with the diuretic group (6).

Figure 1.

Meta-analysis of prospective clinical trials in elderly patients with hypertension according to first-line treatment strategy. Modified with permission from Messerli FH, Grossman E, Goldbourt U. Are beta-blockers efficacious as first-line therapy for hypertension in the elderly? A systematic review. JAMA 1998;279:1903–1907.

Dissociation of surrogate from real endpoint

Beta-blockers are a prime example of a dissociation of the surrogate endpoint from the real endpoint: despite having a “beneficial” effect on blood pressure (surrogate endpoint), they fail to affect the real endpoints, i.e., heart attack, stroke, and cardiovascular and all-cause morbidity and mortality. This indicates that, at present, millions of elderly hypertensive patients are needlessly exposed to the cost, inconvenience, and adverse effects of betablockers even though they will never harvest any benefits.

Even investigators who, time and again, have recommended beta-blockers as first-line therapy in hypertension have admitted that these agents are inefficient at preventing heart attacks in hypertensive patients (regardless of their age). Thus, Psaty et al state: “Perhaps the most interesting finding from the betablocker component of the meta-analysis is the fact that … betablockers do not appear to prevent coronary events in the primary prevention trials in patients with high blood pressure” (8). It is ironic that studies that clearly documented the inefficacy of the beta-blockers in preventing cardiovascular events provided the fundament upon which the recommendations of the JNC VI were built. Perhaps of even more concern in the MRC study in the elderly is that beta-blockers were associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular events compared with diuretics, even after the difference was adjusted for the decrease in arterial blood pressure (6). Thus, for any given fall in arterial pressure, patients on diuretics fared better than those on beta-blockers (7). Obviously, this indicates either that lowering blood pressure by betablockade confers an ill effect on the cardiovascular system that overrides the beneficial effects of the decrease in pressure or that lowering blood pressure with a diuretic confers a specific benefit irrespective of the decrease in blood pressure.

“Gin-and-tonic” studies

In all prospective studies in which beta-blockers were implied to reduce morbidity and mortality, they were used in combination with a diuretic in the majority of patients. In the Swedish Trial in Old Patients (STOP), more than two thirds of the patients received combination therapy, and no information was provided regarding the effects of beta-blockers or diuretics in monotherapy (9). In the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP), only 21% of patients received atenolol, all in combination with a diuretic (10). In the study of Coope and Warrender, which demonstrated a significant reduction in the rate of strokes, 70% of patients in the treatment group received atenolol and 60% received bendrofluazide, although all of them were initially started on atenolol (11). Coope and Warrender clearly state: “Since patients were not randomized to treatment groups, it is impossible to compare response to the beta-blockers and the diuretics” (11).

It is hard to believe that these studies were considered to be ironclad scientific information documenting that beta-blockers reduce morbidity and mortality in hypertension. One could as well conclude that tonic water causes cirrhosis of the liver from a study in which the majority of patients in the active treatment arm were on gin and tonic, some on gin alone and some on tonic water alone, and no attempt was made to separately assess the effect of the individual ingredients. The studies of Coope and Warrender (11), SHEP (10), and STOP (9) do not allow us to conclude that either beta-blockers alone or the addition of betablockers to the diuretic regimen did, indeed, significantly impact morbidity and mortality. To the contrary, the MRC study in the elderly allows us to conclude that beta-blocker–based therapy is distinctly inferior to diuretic-based therapy and is not different from placebo (6). Given this and the not-so-benign side-effect profile of beta-blockers, can we really blame practicing physicians for not following guidelines?

DIURETICS

In contrast to beta-blocker–based therapy, numerous prospective randomized trials have documented that diuretic-based therapy is effective in reducing morbidity and mortality in hypertensive patients (4). If anything, the benefits of diuretic therapy have been shown to be more marked in the elderly than in younger patients. The effect of diuretics is particularly pronounced with regard to reduction of the risk of stroke and somewhat less impressive with regard to the reduction of the risk of coronary heart disease. However, of particular concern for many years, and even decades, is the possibility that this pharmacological intervention could adversely affect the risk for extracardiovascular diseases. Indeed, the very recent meta-analysis suggesting that long-term diuretic therapy could increase the risk for RCC is of distinct concern (5).

Case-control and cohort studies

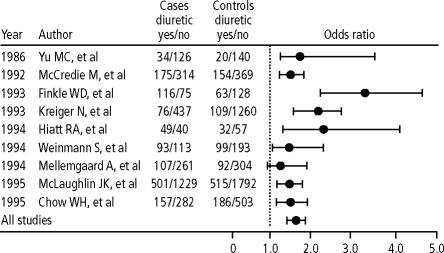

In 9 case studies done in the past decade, an association between RCC and diuretic therapy was documented (odds ratio, 1.55; confidence interval, 1.42 to 1.71; P < 0.00001) (Figure 2) (5). Equally, in 3 cohort studies, in a total study population in excess of 1 million, patients who were taking diuretics had about a 2-fold higher risk of RCC than patients who were not on diuretic therapy (5). In most studies, women were found to have a higher risk of diuretic-associated RCC than men (odds ratio, 2.01 vs 1.69). In 3 studies in which this was examined, the risk of RCC increased with duration of diuretic therapy (cumulative dose). The association between diuretic use and RCC was also found in normotensive subjects who took diuretics for other reasons, and it persisted even when corrected for the presence of hypertension in the majority of the studies.

Figure 2.

Case-control studies assessing the relationship between renal cell carcinoma and diuretic use. Reprinted from American Journal of Cardiology, volume 83, Grossman E, Messerli FH, Goldbourt U, Does diurectic therapy increase the risk of renal cell carcinoma?, 1090–1093, copyright 1999, with permission from Excerpta Medica Inc.

It is unlikely that hypertension itself was the common denominator accounting for the association between RCC and diuretic therapy. Indeed, it seems more likely that hypertension is merely an innocent bystander. There are no plausible clinical, biochemical, or pathophysiological reasons why hypertension, per se, should be a risk for RCC. However, the long-standing presence of hypertension in any patient is intrinsically linked to diuretic use. Most patients will not remember taking a diuretic because numerous fixed combinations containing diuretics are on the market. As most clinicians will easily concede, it is next to impossible to perform a “correction” for the presence of hypertension (that is, to retrospectively separate hypertensive patients who used diuretics during the past 20 to 30 years from those who did not) as has been attempted in many studies. It seems more likely that the common denominator linking hypertension to RCC is, indeed, diuretic use. Regardless of these deliberations, in 5 of the 9 case-control studies, the risk of RCC with diuretic use persisted and remained significant even after adjustment for potentially confounding cofactors.

Hypothetical carcinogenic mechanism

Perhaps one of the most convincing arguments for the connection between RCC and diuretic use is that RCC arises from the renal tubular cell, the main target of the diuretic's pharmacologic effect. Conceivably, the chronic chemical bombardment of this cell over years or decades may have a low-grade carcinogenic effect.

Hydrochlorothiazide is a cyclic imide and can be converted in the stomach to a mutagenic nitroso derivative that is excreted in the kidneys (12, 13). Diuretics have been associated with both nephropathy and renal cell tumors in animals (14, 15). The thiazide diuretics cause massive degenerative changes and cell death in the distal tubule in rats (16). After thiazide exposure, these cells looked like tumor cells and exhibited markers of tumor cells (16).

Gender difference

RCC is a relatively rare malignancy that occurs 2 to 3 times more often in men than in women. The fact that most studies in our meta-analysis document women to be at a higher risk than men with regard to diuretic-induced RCC suggests the presence of a hormonal mechanism. Indeed, estrogens have been shown to enhance the thiazide effect in the distal tubule of ovariectomized rats (17). This effect could possibly account for the inverse gender predominance with regard to diuretic-associated RCC. In addition, although the use of diuretics has declined over the past decade, women still use 2 to 3 times more diuretic therapy than men do, possibly because women have a greater tendency for edema than men (18).

Lack of RCC evidence in prospective randomized trials

Carcinogenicity of diuretic therapy is low and certainly less than that of smoking for lung cancer. If one had to design a prospective randomized trial proving that smoking caused lung cancer, a study duration of at least 1 decade, but preferably 2 decades, would be required. Given the comparatively weak carcinogenicity of diuretic therapy, it probably would take longer to document a difference with regard to RCC. Therefore, it is hardly surprising that in none of the prospective randomized trials, duration of which is usually <5 years, was an excess of RCC found.

Diuretics were introduced into medicine in 1958. Since it probably takes more than 20 years of diuretic exposure to significantly increase the risk of RCC, we are only now seeing this association. Of note, the incidence of RCC has increased by 43% over the past 15 years (19).

True risk-to-benefit ratio

Several epidemiologic studies, such as SHEP and MRC, allow us to estimate the true risk-to-benefit ratio of diuretic therapy in hypertension. It can be estimated that diuretic therapy leading to 1 case of RCC will prevent 20 to 40 strokes, 3 to 28 heart attacks, and 4 to 18 deaths in the general population (20). In the elderly, for whom diuretics are particularly efficacious, the risk-to-benefit ratio may look even better. However, in middle-aged women, only 6 strokes, 2 heart attacks, and no deaths are prevented for 1 case of RCC (20). The actual risk-to-benefit ratio would clearly argue against the use of diuretics in this age and gender group.

We believe that younger and middle-aged women, therefore, probably should no longer be treated with diuretics for hypertension because they potentially will be exposed to these drugs for several decades, they have a well-known tendency to overuse diuretics, they are less protected by diuretics against cardiovascular morbidity and mortality than men, and their risk of diuretic-associated RCC is higher than that in men. In contrast, in patients with congestive heart failure and other forms of edema, the low-grade carcinogenicity of diuretic therapy can possibly be disregarded because their life expectancy is relatively short, and they are unlikely to live long enough for the cumulative diuretic dose to reach the threshold of carcinogenicity.

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Both diuretics and beta-blockers have been used to treat essential hypertension for more than 3 decades. Both of these drug classes have impressive safety records that are unparalleled by other drugs. Despite this, no prospective randomized study has shown that beta-blockers, either in monotherapy or when added to diuretic therapy, diminish cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Quite to the contrary, our recent meta-analysis in the elderly reported little if any benefits of beta-blocker therapy when compared with placebo or other therapy, although blood pressure was lowered by the beta-blockers.

The inefficacy of beta-blockers may come from their unfavorable effects on systemic hemodynamics and on other pathophysiologic findings in the hypertensive patient, such as arterial stiffness, hypertensive heart disease, kidney disease, and cerebrovascular disease. In addition, comorbid conditions often present in the elderly, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes mellitus, depression, and erectile dysfunction, are relative contraindications to the use of beta-blockers. It is ironic that the same studies that demonstrate the inefficacy of beta-blockers in the elderly were used as an argument to promote them to a preferred status.

Recent data showing low-grade carcinogenicity for RCC with diuretic therapy must be seen in proper context. In the elderly, the cardiovascular benefits of diuretics clearly outweigh the low-grade risk of RCC. However, in younger patients, particularly in women, diuretics probably should no longer be used as initial antihypertensive therapy. In view of the unparalleled safety and efficiency of diuretics, no conclusions should be drawn with regard to safety and efficacy of other antihypertensive drugs.

In conclusion, sweeping recommendations for the use of beta-blockers and diuretics as “preferred” therapeutic strategies are inappropriate. In hypertension, as is usually the case in medicine, a more sophisticated approach is needed.

References

- 1.The sixth report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:2413–2446. doi: 10.1001/archinte.157.21.2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.1999 World Health Organization–International Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension. Guidelines Subcommittee J Hypertens. 1999;17:151–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veterans Administration Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension. II. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressure averaging 90 through 114 mm Hg. JAMA. 1970;213:1143–1152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Messerli FH, Grossman E, Goldbourt U. Are beta-blockers efficacious as first-line therapy for hypertension in the elderly? A systematic review. JAMA. 1998;279:1903–1907. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.23.1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grossman E, Messerli FH, Goldbourt U. Does diuretic therapy increase the risk of renal cell carcinoma? Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:1090–1093. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medical Research Council trial of treatment of hypertension in older adults: principal results. MRC Working Party BMJ. 1992;304:405–412. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6824.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lever AF, Brennan PJ. MRC trial of treatment in elderly hypertensives. High Blood Press. 1992;1:132–137. doi: 10.3109/10641969309037083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Psaty BM, Smith NL, Koepsell TD, Furberg CD. In reply [letter] JAMA. 1997;277:1759–1760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dahlöf B, Lindholm LH, Hansson L, Scherstén B, Ekbom T, Wester PO. Morbidity and mortality in the Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension (STOP-Hypertension) Lancet. 1991;338:1281–1285. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92589-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). SHEP Cooperative Research Group. JAMA. 1991;265:3255–3264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coope J, Warrender TS. Randomised trial of treatment of hypertension in elderly patients in primary care. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;293:1145–1151. doi: 10.1136/bmj.293.6555.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gold B, Mirvish SS. N-Nitroso derivatives of hydrochlorothiazide, niridazole, and tolbutamide. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1977;40:131–136. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(77)90124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lijinsky W, Epstein SS. Nitrosamines as environmental carcinogens. Nature. 1970;225:21–23. doi: 10.1038/225021a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lijinsky W, Reuber MD. Pathologic effects of chronic administration of hydrochlorothiazide, with and without sodium nitrite, to F344 rats. Toxicol Ind Health. 1987;3:413–422. doi: 10.1177/074823378700300313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bucher JR. Toxicology and carcinogenesis studies of furosemide (CAS No. 54-31-9) in F344/N rats and B6C3F1 mice (feed studies). Technical Report Series, No. 356. NIH Publication #89, 2811. Bethesda, Md: National Institutes of Health, 1989:190. [PubMed]

- 16.Loffing J, Loffing-Cueni D, Hegyi I, Kaplan MR, Hebert SC, Le Hir M, Kaissling B. Thiazide treatment of rats provokes apoptosis in distal tubule cells. Kidney Int. 1996;50:1180–1190. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verlander JW, Tran TM, Zhang L, Kaplan MR, Hebert SC. Estradiol enhances thiazide-sensitive NaCl cotransporter density in the apical plasma membrane of the distal convoluted tubule in ovariectomized rats. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1661–1669. doi: 10.1172/JCI601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klungel OH, de Boer A, Paes AH, Seidell JC, Bakker A. Sex differences in antihypertensive drug use: determinants of the choice of medication for hypertension. J Hypertens. 1998;16:1545–1553. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199816100-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vogelzang NJ, Stadler WM. Kidney cancer. Lancet. 1998;352:1691–1696. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)01041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Messerli FH, Grossman E, Goldbourt U. Diuretic therapy and renal cell carcinoma—what is the true risk/benefit ratio? [abstract] Am J Hypertens. 1999;12:137a. [Google Scholar]