Abstract

Basophils and mast cells, which are selectively endowed with the high-affinity IgE receptor and mediate a range of adaptive and innate immune responses, have an unknown developmental relationship. Here, by evaluating the expression of the β7 integrin, a molecule that is required for selective homing of mast cell progenitors (MCPs) to the periphery, we identified bipotent progenitors that are capable of differentiating into either cell type in the mouse spleen. These basophil/mast cell progenitors (BMCPs) gave rise to basophils and mast cells at the single-cell level and reconstituted both mucosal and connective tissue mast cells. We also identified the basophil progenitor (BaP) and the MCP in the bone marrow and the gastrointestinal mucosa, respectively. We further show that the granulocyte-related transcription factor CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein α (C/EBPα) plays a primary role in the fate decision of BMCPs, being expressed in BaPs but not in MCPs. Thus, circulating basophils and tissue mast cells share a common developmental stage at which their fate decision might be controlled principally by C/EBPα.

Keywords: integrin, progenitor, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein

Basophils and mast cells exhibit distinct differentiation patterns despite their multiple shared phenotypic characteristics. Both cell types express the αβγ2 form of the high-affinity receptor for IgE (FcεRI). Crosslinking of the high-affinity receptor for IgE (FcεRI) on tissue mast cells triggers immediate hypersensitivity with local symptoms, and sequential recruitment of basophils to these tissue sites expands the spectrum of this inflammatory process (1). By secreting diverse inflammatory protein mediators, they provide innate defense against parasitic or bacterial infections (2-4) and also play a critical role in the development of a variety of autoimmune disorders (5). A marked increase in activated intraepithelial and bronchial smooth muscle mast cells characterizes bronchial asthma, and a prominent basophil infiltration is noted with fatal diseases. In cutaneous allergic diseases, mast cell activation is the basis of itching hives, whereas basophils are abundant in contact hypersensitivity eruptions (6). However, basophils exist as mature cells in the circulation, whereas mast cells circulate as progenitors and complete their maturation after migration into peripheral tissues such as the skin, heart, lung, and the gastrointestinal mucosa. Their origin and developmental relationships remain as one of the major issues in the biology of hematopoiesis (7) and in the pathobiology of allergic diseases.

In adult mice, the intestine is the main peripheral tissue harboring mast cell colony-forming activity (8). We have shown that the β7-integrin (β7) is an essential molecule for tissue-specific homing of putative precursors for intestinal mast cells (8) and that mast cell potential resides mostly in the c-Kit+ fraction, at least in the murine bone marrow (9). To identify a candidate population that seeds putative intestinal progenitors for mast cells, we evaluated the expression level of β7 in hematopoietic progenitor populations in the bone marrow, the spleen, and the intestine. This approach enabled us to isolate a set of progenitor populations that have committed to the basophil and/or mast cell lineages. Our data show that basophils and mast cells share the common progenitor stage, where CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein α (C/EBPα), the transcription factor essential for granulocyte development (10), plays a critical role in their fate decision.

Materials and Methods

Mice. C57BL/6J, B6.SJL-Ptprca Pep3b/BoyJ, and WBB6F1/J-KitW/KitW-v mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. C/EBPαF/F mice were developed as described in ref. 11. They were bred and maintained in the Research Animal Facility at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Antibodies, Cell Staining, and Sorting. Myeloid and lymphoid progenitors were purified as described in refs. 12 and 13. For the staining of lineage antigens, phycoerythrin (PE)-Cy5-conjugated rat antibodies specific for CD3 (CT-CD3), CD4 (RM4-5), CD8 (5H10), B220 (6B2), Gr-1 (8C5), and CD19 (6D5) (Caltag, Burlingame, CA) were used. For basophil/mast cell progenitor (BMCP) sorting, spleen cells were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-T1/ST2, PE-conjugated anti-β7 integrin, allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti-c-Kit (2B8), and biotinylated anti-FcγRII/III (2.4G2) (BD Pharmingen), followed by avidin-APC/Cy7 (Caltag). For basophil progenitor (BaP) or mast cell progenitor (MCP) sorting, bone marrow or intestinal cells were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD34 (RAM34) (BD Pharmingen), PE-conjugated anti-FcεRIα (MAR-1), APC-conjugated anti-c-Kit (2B8), and/or APC/Cy7-conjugated anti-CD45.2 (104). Cells were double-sorted by using a highly modified double-laser (488-nm/350-nm Enterprise II and 647-nm Spectrum) FACS (Moflo-MLS, Cytomation, Fort Collins, CO). Cells were doubly sorted and were deposited into 60-well Terasaki plates by using an automatic cell deposition unit system (14).

Infection with Trichinella spiralis and Ovalbumin (OVA) Sensitization. The method for T. spiralis infection has been reported previously (14). For the OVA sensitization, mice were immunized i.p. twice with OVA (10 μg, Sigma-Aldrich) adsorbed to 1 mg of alum (Pierce) 7 days apart. Ten days after the second immunization, the mice were exposed to an aerosol of 1% OVA in PBS for 30 min by using a PARI nebulizer (PARI Respiratory Equipment, Midlothian, VA). Mice were analyzed 1 day after the fifth daily exposure.

Cell Cultures. Cells were cultured in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium supplemented with 20% FCS. Cultures were performed in the presence of cytokine cocktails containing murine stem cell factor (20 ng/ml), IL-3 (20 ng/ml), IL-5 (50 ng/ml), IL-6 (20 ng/ml), IL-7 (20 ng/ml), IL-9 (50 ng/ml), IL-11 (10 ng/ml), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (10 ng/ml), erythropoietin (2 units/ml), and thrombopoietin (10 ng/ml) (R & D Systems). Cells were cultured at 37°C in a humidified chamber under 5% CO2.

In Vivo Reconstitution Assay. Four hundred splenic BMCPs or intestinal MCPs were purified from C57BL/6 (Ly5.1) mice and injected i.p. into nonirradiated W/Wv mice. Eight weeks after the injection, peritoneal lavage cells were analyzed. Three thousand purified BMCPs (Ly5.1) were also injected intravenously into W/Wv mice after 2.5-Gy irradiation. Mice were analyzed 12 weeks after transplantation.

Retroviral Transduction. A Cre and a mouse C/EBPα cDNA were subcloned into the EcoRI site of MSCV-ires-EGFP (MIG) vector. The virus supernatant was obtained from the cultures of 293T cells cotransfected with the target retrovirus vector, gagpol-, and VSV-G-expression plasmids by using a standard CaPO4 coprecipitation method. BMCPs and BaPs were purified from C/EBPαF/F mice and infected with MIG-Cre retroviruses, as reported in ref. 11.

Results

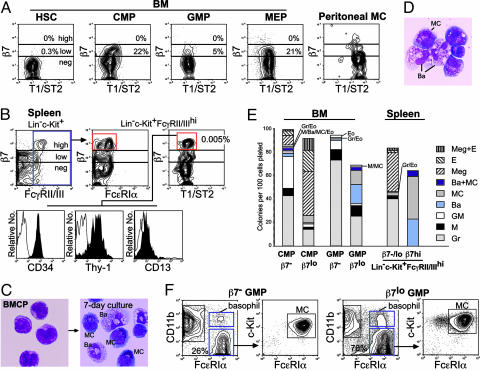

A Population Expressing a High Level of β7 Resides in the Spleen but Not in the Bone Marrow. We evaluated the expression of β7 within stem/progenitor populations that did not express a panel of lineage antigens (Lin) but expressed c-Kit. In the bone marrow, Lin-Sca-1+c-Kit+ hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) did not express β7, but a low level of β7 expression was found in a fraction of progenitor populations, such as common myeloid progenitors (CMPs), megakaryocyte/erythrocyte progenitors (MEPs), and granulocyte/monocyte progenitors (GMPs) (13) (Fig. 1A). In contrast, cells expressing β7 at high levels were found in the Lin-c-Kit+ fraction of the spleen. These β7hi cells existed only in a fraction expressing FcγRII/III (Fig. 1B), at a level comparable to that in GMPs (13), neutrophils, and monocytes (not shown). β7hi spleen cells expressed CD34, a marker for hematopoietic progenitors that can generate mast cells and basophils (15) and for mature mast cells (16). They also expressed Thy-1, which is expressed also at a low level in HSCs (17) and fetal blood mast cell precursors (18), and were positive for CD13, a marker for myelomonocytic cells at a low level (Fig. 1B). T1/ST2, which is highly expressed in mature mast cells (19), was expressed at a low level in β7hi spleen cells, as also occurs in other myeloerythroid progenitors (Fig. 1 A and B). The majority of Lin-c-Kit+FcγRII/IIIhiβ7hi spleen cells did not react significantly with an anti-FcεRIα monoclonal antibody (Mar-1) (Fig. 1B), whereas FcεRIα mRNA was detectable by RT-PCR analysis (not shown). They bore a blastic morphology and had scattered very fine metachromatic granules (Fig. 1C Left).

Fig. 1.

Identification of BMCPs in C57BL/6 murine hematopoiesis. (A) The expression of β7 and T1/ST2 in the bone marrow myeloerythroid progenitors and peritoneal mast cells (MC). A fraction of myeloerythroid progenitors expressed a low level of β7. (B) The surface phenotype of β7hi BMCPs in the spleen. (C)(Left) Morphology of purified Lin-c-Kit+FcγRII/IIIhiβ7hi BMCPs. These cells gave rise exclusively to mast cells and basophils (Right) in the presence of a panel of myeloerythroid cytokines (see Materials and Methods). May-Giemsa staining was used. (Magnification: ×1,000.) (D) A basophil/mast cell colony developed from a single BMCP in vitro. May-Giemsa staining was used. (Magnification: ×1,000.) (E) Clonogenic analysis of β7lo bone marrow myeloerythroid progenitors and β7hi BMCP. Note that a fraction of the spleen BMCP and the bone marrow β7lo GMP gave rise to both basophils and mast cells at the single-cell level. (F) FACS analysis of day-7 progeny of the bone marrow β7- and β7lo GMP. Both populations gave rise to FcεRIα+CD11c+ basophils and FcεRIα+CD11c- mast cells expressing c-Kit.

Spleen β7hi Cells Exclusively Gave Rise to Basophils and Mast Cells at the Single-Cell Level. We cultured Lin-c-Kit+FcγRII/IIIhiβ7hi cells in the presence of a panel of myeloerythroid cytokines. After 7 days, these cells exclusively differentiated into mast cells and basophils (Fig. 1C Right). Cells of other myeloerythroid lineages were never detected in these cultures. Furthermore, single Lin-c-Kit+FcγRII/IIIhiβ7hi cells formed colonies containing both basophils and mast cells (Fig. 1D), as well as ones containing either type (Fig. 1E Right), indicating that at least a fraction of Lin-c-Kit+FcγRII/IIIhiβ7hi spleen cells was bipotent for the basophil and mast cell lineages. We thus named these spleen β7hi cells as BMCPs. In contrast, spleen β7-/lo cells formed a variety of myeloerythroid colonies (Fig. 1E Right), suggesting that the expression of a high level of β7 marks exclusively the mast/basophil potential. Interestingly, in the bone marrow, a fraction of MEPs was β7lo, and cells with megakaryocyte/erythroid (MegE) potential were more concentrated in the β7lo fraction of CMPs compared with the β7- ones, suggesting that a low level of β7 up-regulation could also occur in association with the MegE lineage commitment (Fig. 1E Left). Colonies related to the basophil/mast cell lineage were formed in a fraction (<5%) of both β7- and β7lo CMPs.

In liquid cultures of 100 cells, both β7- and β7lo GMPs generated FcεRIhiCD11b-c-Kit+ mast cells and FcεRIhiCD11b+c-Kit- basophils in addition to FcεRI-CD11b+ neutrophils/monocytes (Fig. 1F). In GMPs, however, the basophil/mast cell potential was enriched in the β7lo fraction because ≈40% of single β7lo GMPs formed basophil/mast cell-related colonies, including ones containing both types of cells (Fig. 1E Right). These data suggest that within the GMP population, β7 is gradually up-regulated in association with the activation of the mast cell/basophil developmental program.

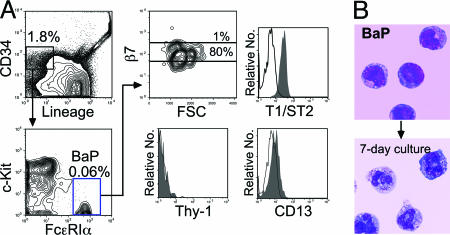

Identification of BaPs in the Bone Marrow. To separate monopotent progenitors for either the basophil or the mast cell lineage that may exist downstream of BMCPs, we used CD34 as a positive marker. The Lin-CD34+ bone marrow, but not spleen cells, contained a FcεRIαhic-Kit- population, which differentiated exclusively into mature basophils (Fig. 2). Almost 40% of single cells gave rise to small clusters containing 10-40 basophils. The Lin-CD34+FcεRIαhic-Kit- bone marrow population was thus named as the BaP. BaPs expressed only a low level of β7 (Fig. 2 A), which was shut down in mature basophils (not shown). They did not express Thy-1 but expressed CD13 and T1/ST2 at low levels that were comparable to those in BMCPs (Fig. 2 A).

Fig. 2.

Identification of BaPs in the bone marrow. (A) FACS analysis of Lin-CD34+FcεRIαhic-Kit- BaPs in the bone marrow for β7, T1/ST2, CD13, and Thy-1. (B) The BaPs possessed a blastic morphology and differentiated only into basophils. May-Giemsa staining was used. (Magnification: ×1,000.)

Identification of Mast Cell Lineage-Committed Progenitors in the Intestine. We then searched for basophil/mast cell-related progenitors within the intestine, where mast cell potential is highly enriched. Lin- intestinal mononuclear cells expressing CD45, a marker for hematopoietic cells (20), gave rise only to mast cell colonies. As expected, a fraction of CD45+Lin-CD34+ intestinal cells contained β7hi cells that expressed a low level of FcεRIα (Fig. 3A Top). Purified intestinal CD45+Lin-CD34+β7hiFcεRIαlo cells were blastic, possessing a few scattered metachromatic granules, and gave rise exclusively to pure mast cell colonies (Fig. 3B) at a 30-40% plating efficiency. We thus named this population as intestinal MCPs. Intestinal MCPs were FcγRII/III+, c-Kitlo, and Thy-1- (Fig. 3C) but differentiated only into FcεRIαhic-Kithiβ7- mature mast cells (not shown). W/Wv mice did not possess intestinal MCPs (Fig. 3A Middle), in agreement with our previous study (8).

Fig. 3.

Identification of MCPs in the intestine. (A) FACS analysis of intestinal MCPs in normal (Top), W/Wv (Middle), and OVA-sensitized (Bottom) mice. (B) (Left) Morphology of purified intestinal MCPs. Intestinal MCPs formed colonies, which contained only mast cells (Right). May-Giemsa staining was used. (Magnification: ×1,000.) (C) Expression of mast cell-related antigens in purified intestinal MCPs. (D) Changes in the absolute numbers of BMCPs and BaPs in mice infected with T. spiralis and in uninfected mast cell-deficient W/Wv mice. The error bars represent the standard deviation.

BMCP, BaP, and MCP Populations Expand in Vivo by Helminth Infection or Allergy Induction. To test the physiological significance of the isolated progenitor populations, we infected mice with T. spiralis, because helminth infection increases the number of intestinal mast cells (21). Infected mice displayed ≈2- and ≈3-fold increases in the number of spleen BMCPs and bone marrow BaPs, respectively (Fig. 3D). In contrast, W/Wv mice, which lack mast cells (22) because of an impairment of c-Kit signaling, did not possess spleen BMCPs and had one-third the number of BaPs (Fig. 3D). Because we were unable to recover sufficient numbers of mononuclear cells from the highly inflamed intestine of helminth-infected mice, we sensitized mice by OVA and analyzed these mice after five aerosolized OVA challenges. This treatment induced significant expansion of intestinal MCPs (4-fold) (Fig. 3A Bottom). These data strongly suggest that previously unidentified BMCPs, BaPs, and intestinal MCPs are involved in the physiological in vivo production of basophils and mast cells.

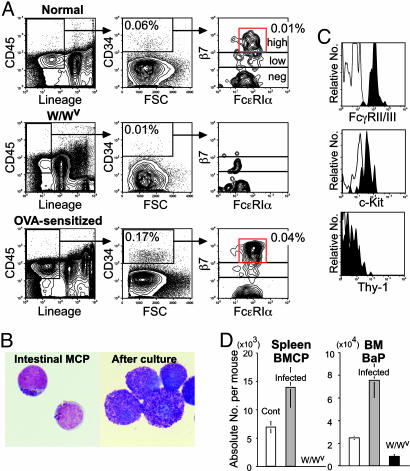

Lineal Relationships of BMCPs, BaPs, and MCPs. In liquid cultures, mast cells and basophils developed from bone marrow CMPs and GMPs but not from MEPs (13) or lymphoid progenitors, including common lymphoid progenitors (12) and proB and proT cells (not shown). Eight of 1,358 single GMP cultures showed clonal development of mast cells, basophils, and neutrophils (Fig. 4A). Thus, the fate decision into the basophil and mast cell lineages appears to occur along the myelomonocytic pathway. This finding is compatible with the previous report that human CD13+CD34+c-Kit+ cells in the blood mainly differentiated into monocytes and mast cells (23).

Fig. 4.

Lineal relationship of BMCPs, BaPs, and MCPs. (A) A single GMP-derived colony contained neutrophils, basophils, and mast cells. May-Giemsa staining was used. (Magnification: ×600.) (B) FACS analysis of the day-3 progeny of GMPs cultured in the presence of stem cell factor (SCF), IL-3, IL-5, IL-6, and IL-9. In addition to Lin-CD34+IL-5Rα+c-Kitlo EoPs (14), BMCPs, BaPs, and MCPs were isolatable within the GMP progeny. (C) FACS analysis of day-2 progeny of spleen BMCPs. BMCPs exclusively developed BaPs and MCPs. Morphology of BMCP-derived BaP and MCP populations and of their progeny after 7-day cultures are also shown. May-Giemsa staining was used. (Magnification: ×1,000.) (D) Proliferation curve of single BMCPs, BaPs, and MCPs in the presence of SCF, IL-3, and IL-6. (E) FACS analysis of the reconstitution of peritoneal mast cells 8 weeks after i.p. transplantation of 400 BMCPs or 400 intestinal MCPs purified from C57BL/6 (Ly5.1) mice into W/Wv mice (Ly5.2). (F) Successful reconstitution of mast cells in the spleen and the gastrointestinal submucosa of W/Wv mice 12 weeks after i.v. injection of 3,000 BMCPs.

In cultures of 100 GMPs, the day-3 progeny contained the Lin-CD34+IL-5Rα+c-Kitlo eosinophil lineage-committed progenitor (EoP) population, as we reported previously (14), whereas the Lin-CD34+IL-5Rα- fraction contained FcεRIα-/loc-Kithi BMCPs and FcεRIαhic-Kit- BaPs (Fig. 4B). GMPs also produced the FcεRIαhic-Kithi cells that gave rise only to mast cells in vitro (Fig. 4B; GMP-derived MCPs). In 2-day cultures of purified spleen BMCPs, they quickly up-regulated FcεRIα, giving rise to Lin-FcεRIαhic-Kit+ and Lin-FcεRIαhic-Kit- blastic cell populations (Fig. 4C). Both populations expressed CD34 (not shown), and by an additional 7-day culture, they differentiated exclusively into mast cells and basophils, respectively (Fig. 4C). These results strongly suggest that GMPs can generate EoPs and BMCPs and, further, that BMCPs can produce BaPs and MCPs.

Mast Cell Reconstitution Activity of BMCPs and Intestinal MCPs. Single BMCPs continued to proliferate in the presence of IL-3 and stem cell factor at least for 3 weeks and generated >106 to 107 mast cells in vitro, whereas intestinal MCPs ceased cell division by 2 weeks, resulting in generation of 103 to 105 mature mast cells (Fig. 4D). These results support the concept that intestinal MCPs are downstream of spleen BMCPs and possess a limited half-life (24). BaPs also exhibited limited expansion capacity. We then tested their in vivo reconstitution potential: 400 BMCPs could restore peritoneal mast cells in W/Wv mice up to a normal level 8 weeks after an i.p. injection, but the same number of intestinal MCPs restored only 10% of normal levels (compare gated cells in Fig. 4E Left). We also intravenously injected 3,000 BMCPs into W/Wv mice. As shown in Fig. 4F, BMCPs successfully differentiated into mature mast cells possessing chloroacetate esterase activity in the spleen and stomach, indicating that BMCPs can provide both connective tissue and mucosal mast cells.

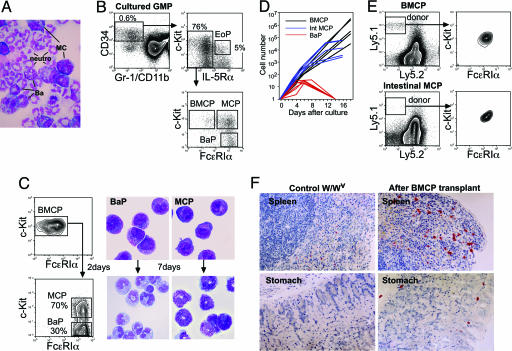

C/EBPα Plays a Pivotal Role in Basophil vs. Mast Cell Lineage Fate Decision. Each purified population was subjected to RT-PCR analyses to test the expression profiles of lineage-related genes (Fig. 5A). Major basic protein was expressed in BMCPs and BaPs but not in MCPs, whereas murine mast cell protease (mMCP) 1 and mMCP-5 were expressed in BMCPs and MCPs but not BaPs. GATA-1 is expressed in mature eosinophils, basophils, and mast cells (25) as well as MEPs (13) and was expressed in all populations tested, except for GMPs. PU.1 is essential for GM, B, and mast cell development (26), and its expression was observed in all populations tested. The mi transcription factor, which is essential for mast cell development (27), was highly expressed in BMCPs, MCPs, and mature mast cells but was shut down in BaPs. Interestingly, C/EBPα was expressed in BMCPs at a low level and, by a real-time PCR analysis, was up-regulated 6-fold in BaPs. In contrast, C/EBPα was down-regulated in MCPs up to ≈10 and 2% relative to the levels in BMCPs and BaPs, respectively (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

C/EBPα plays a key role in the bifurcation of mast cell vs. basophil lineage fates. (A) RT-PCR analyses of lineage-related gene expression in purified progenitor populations. GMPs and BaPs were purified from the bone marrow, and BMCPs were from the spleen of C57BL/6 mice. MCP, GMP-derived MCPs after in vitro culture (see text and Fig. 3B); Int MCP, intestinal MCPs; PMC, peritoneal mast cells. (B) A quantitative real-time PCR assay for C/EBPα mRNA in purified populations. (C) FACS analyses of progeny of spleen BMCPs with or without C/EBPα. BMCPs isolated from the spleen of C/EBPαF/F mice were infected with retroviruses carrying control GFP (Left), Cre recombinase (Center), or C/EBPα (Right). GFP+ cells were phenotyped after 7 days in culture. (D) FACS analyses of progeny of bone marrow BaPs disrupted with C/EBPα. BaPs differentiated only into c-Kit-CD11b+ basophils in vitro, irrespective of C/EBPα disruption. (E) Analysis of intestinal MCPs transduced with C/EBPα. MCPs infected with control retroviruses differentiated exclusively into CD11b-c-Kit+ mature mast cells, whereas those transduced with C/EBPα converted into CD11b+c-Kit- basophils. The morphology of progeny of GMP-derived MCPs transduced with control retroviruses (Lower Left) and with C/EBPα (Lower Right) is also shown. May-Giemsa staining was used. (Magnification: ×1,000.) (F) RT-PCR analyses of basophil-related genes in progeny of MCPs with or without ectopic expression of C/EBPα. P, positive control.

Because the expression of C/EBPα was dramatically increased in BaPs but was diminished in MCPs, we hypothesized that it plays a key role in the basophil vs. mast cell lineage commitment at the BMCP stage. To test this hypothesis, we disrupted C/EBPα at the BMCP stage by using the conditional C/EBPα knockout system (11). BMCPs and BaPs were purified from the spleen and bone marrow of C/EBPαF/F mice, respectively, and were infected with GFP-tagged retrovirus carrying a Cre recombinase (MIG-Cre) to excise C/EBPα loci (11). BMCPs transduced with empty retroviruses (C/EBPαF/F BMCP) differentiated into both FcεRIαhic-Kit+CD11b- mast cells and FcεRIαhic-Kit-CD11b+ basophils (Fig. 5C Left), whereas BMCPs transduced with MIG-Cre retroviruses (C/EBPαΔ/Δ BMCP) were differentiated exclusively into mast cells (Fig. 4C Center). Further, BMCPs overexpressing C/EBPα by a retroviral transduction differentiated mainly into FcεRIαhic-Kit-CD11b+ basophils (Fig. 5C Right). In contrast, when C/EBPαF/F bone marrow BaPs were transduced with MIG-Cre retroviruses, the C/EBPαΔ/Δ BaPs differentiated normally into mature basophils, suggesting that C/EBPα is not required for late basophil maturation after the BaP stage (Fig. 5D). We then transduced C/EBPα into intestinal or GMP-derived MCPs. Surprisingly, these MCPs with ectopic C/EBPα displayed the lineage conversion into c-Kit-CD11b+ basophils (Fig. 5E). These basophils converted from MCPs had a high level of FcεRIα and major basic protein that is expressed also in normal EoPs (14). However, they did not express EoP-specific IL-5Rα (Fig. 5F) or eosinophil peroxidase (not shown). Thus, reprogramming into the basophil lineage can be induced even after the completion of mast cell lineage commitment simply by the ectopic expression of C/EBPα, confirming the instructive role of C/EBPα in the basophil lineage commitment at the BMCP stage.

Discussion

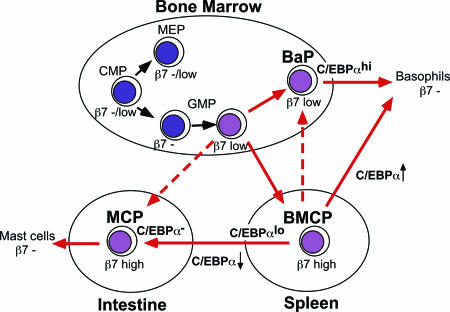

The possibility of a common origin of basophils and mast cells had been raised previously (28) based on their phenotypic similarities, including the selective expression of the ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 3 (CD203c) in human basophils and mast cells (29) and the existence of basophils with phenotypic features characteristic of mast cells in patients with asthma, allergy, or allergic drug reactions (30). By purifying the BMCP population, we directly prove that basophils and mast cells are siblings that share a common progenitor stage in normal murine hematopoiesis. The proposed scheme of mast cell/basophil development is shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

The proposed developmental scheme of basophil and mast cell development.

Our data show that the expression of a high level of β7 is a specific marker for BMCPs. The fact that MCPs but not BaPs or BMCPs could be isolated from the intestine suggests that BMCPs have completed their commitment into the mast cell lineage before or shortly after their immigration into this peripheral tissue. Consistent with this migration, BMCPs and the intestinal MCPs expressed high levels of β7, which is required for their selective homing to the intestine (8). Thus, the spleen β7hi BMCP might be a precursor for β7hi intestinal MCPs in steadystate hematopoiesis. In contrast, the bone marrow had only β7lo cells, and the majority of β7lo cells were committed to the megakaryocyte/erythroid lineage, indicating that β7 expression at a low level does not mark the basophil/mast cell lineage commitment. Interestingly, however, β7lo GMPs were enriched for basophil/mast cell potential, and a fraction of them displayed bipotency for basophils and mast cells (Fig. 1E). In contrast to a recent report showing that β7+ but not β7- CMPs/GMPs gave rise to mast cells (31), in our hands, β7- GMPs/CMPs still possessed potent mast cell/basophil potential (Fig. 1 E and F). Although we do not know the reason for this discrepancy, our data suggest that commitment into the basophil/mast cell lineage does not occur abruptly at the BMCP stage, but gradually initiates within the β7lo fraction of GMPs in the bone marrow. Thus, our data collectively suggest that the bone marrow β7lo GMPs immigrate into the spleen to form β7hi BMCPs (Fig. 6).

The spleen environment, however, is not absolutely required for generation of BaPs and MCPs, because we could find significant numbers of BaPs and intestinal MCPs in splenectomized mice (unpublished data). Therefore, β7lo GMPs might be able to directly provide either bone marrow BaPs or intestinal MCPs, particularly when the spleen is absent (Fig. 6). β7lo BaPs may also develop directly from β7lo GMPs within the bone marrow in normal hematopoiesis. It is, however, also possible that the spleen BMCP migrates into the bone marrow to distribute BaPs and some MCPs (Fig. 4B). Previous reports showed that MCPs existed within the AA4-BGD6+CD34+ BALB/c (32) or the β7+T1/ST2+ C57BL/6 bone marrow populations (31). We could not separate mast cell potential within the β7lo bone marrow fraction by positive expression of T1/ST2 cells, because BaPs and myeloerythroid progenitors such as CMPs, GMPs, and MEPs in the bone marrow expressed equivalent levels of T1/ST2 (Figs. 1 A and 2 A). Because we observed that a fraction of β7lo GMPs have both mast cell and basophil potential (Fig. 1 E and F), it is of interest to know whether bone marrow MCPs reported in these papers (31, 32) can give rise to basophils.

A previous paper reported that Lin-Thy1loc-Kit+ cells in the fetal blood gave rise exclusively to mast cells (18). Interestingly, this phenotype is shared by hematopoietic stem cells in the fetal liver (33). Neither we nor Rodewald et al. (18), however, could detect cells of this phenotype in the adult blood (<0.001% of total cells; data not shown). These data suggest that the detectable levels of circulating MCPs appear transiently in the developing fetus to seed mast cells into the peripheral tissues. That the physiologic or pathobiologic level of blood MCP providing the intestinal reservoir (34) is below or transiently at the level of detection may be explained by a rapid β7-dependent clearance into that tissue.

Importantly, the basophil lineage vs. the mast cell lineage at the BMCPs could be controlled simply by C/EBPα, as in the case of the monocyte lineage vs. the neutrophil lineage at the GMP stage (35). Commitment of BMCPs into the basophil lineage depended on C/EBPα, whereas the mast cell differentiation could occur only in the absence of C/EBPα. Furthermore, even intestinal MCPs still possessed plasticity for activating the basophil development program by ectopic C/EBPα expression. C/EBPα is required for the basophil lineage commitment but not for their maturation, which is similar to its role in neutrophil development (35). Thus, C/EBPα might control the mast cell vs. granulocytic basophil fate decision at the BMCP stage, which in turn suggests the physiological importance of the BMCP stage for basophil/mast cell development.

Thus, we have identified β7hi BMCPs in the adult mouse spleen that can give rise exclusively to basophils and mast cells. The spleen BMCP may originate from the β7lo GMP in the bone marrow. Differentiation of spleen BMCPs into monopotent progeny may lead to their selective migration (BaPs to the bone marrow or MCPs to peripheral tissues), and this fate decision is controlled at least in part by C/EBPα. This progenitor allocation may in turn relate to their distinct lineage functions, which are dependent on recruitment of mature mobile basophils from blood and development of mature mucosal and connective tissue mast cells directly from constitutive or augmented tissue-localized progenitors. The previously unidentified BMCPs as well as MCPs and BaPs should be useful in investigating the mechanism of commitment, differentiation, and homing involved in the development of these lineages. These progenitor populations could also be therapeutic targets of a variety of basophil/mast cell-related disorders, including allergic and autoimmune diseases (5).

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the K.A. laboratory for helpful discussions. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants DK061320 and AI063284 (to K.A.), AI031599 and HL036110 (to K.F.A.), AI031599 (to M.F.G.), and HL56745 (to D.G.T.).

Author contributions: K.F.A. and K.A. designed research; Y.A., H.I., M.F.G., S.M., and H.S. performed research; and H.O. and D.G.T. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; and K.A. and Y.A. wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

Abbreviations: MCP, mast cell progenitor; BMCP, basophil/mast cell progenitor; BaP, basophil progenitor; C/EBPα, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein α; OVA, ovalbumin; CMP, common myeloid progenitor; MEP, megakaryocyte/erythrocyte progenitor; GMP, granulocyte/monocyte progenitor; EoP, eosinophil lineage-committed progenitor.

References

- 1.Bochner, B. S. & Schleimer, R. P. (2001) Immunol. Rev. 179, 5-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wedemeyer, J., Tsai, M. & Galli, S. J. (2000) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 12, 624-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Echtenacher, B., Mannel, D. N. & Hultner, L. (1996) Nature 381, 75-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gurish, M. F. & Austen, K. F. (2001) J. Exp. Med. 194, F1-F5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benoist, C. & Mathis, D. (2002) Nature 420, 875-878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sloane, D. E., Tedla, N., Awoniyi, M., Macglashan, D. W., Jr., Borges, L., Austen, K. F. & Arm, J. P. (2004) Blood 104, 2832-2839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galli, S. J. (2000) Curr. Opin. Hematol. 7, 32-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gurish, M. F., Tao, H., Abonia, J. P., Arya, A., Friend, D. S., Parker, C. M. & Austen, K. F. (2001) J. Exp. Med. 194, 1243-1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan, Q., Gurish, M. F., Friend, D. S., Austen, K. F. & Boyce, J. A. (1998) J. Immunol. 161, 5143-5146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang, D. E., Zhang, P., Wang, N. D., Hetherington, C. J., Darlington, G. J. & Tenen, D. G. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 569-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang, P., Iwasaki-Arai, J., Iwasaki, H., Fenyus, M. L., Dayaram, T., Owens, B. M., Shigematsu, H., Levantini, E., Huettner, C. S., Lekstrom-Himes, J. A., et al. (2004) Immunity 21, 853-863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kondo, M., Weissman, I. L. & Akashi, K. (1997) Cell 91, 661-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akashi, K., Traver, D., Miyamoto, T. & Weissman, I. L. (2000) Nature 404, 193-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iwasaki, H., Mizuno, S. I., Mayfield, R., Shigematsu, H., Arinobu, Y., Seed, B., Gurish, M. F., Takatsu, K. & Akashi, K. (2005) J. Exp. Med. 201, 1891-1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirshenbaum, A. S., Goff, J. P., Kessler, S. W., Mican, J. M., Zsebo, K. M. & Metcalfe, D. D. (1992) J. Immunol. 148, 772-777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drew, E., Merkens, H., Chelliah, S., Doyonnas, R. & McNagny, K. M. (2002) Exp. Hematol. 30, 1211-1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spangrude, G. J., Heimfeld, S. & Weissman, I. L. (1988) Science 241, 58-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodewald, H. R., Dessing, M., Dvorak, A. M. & Galli, S. J. (1996) Science 271, 818-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moritz, D. R., Rodewald, H. R., Gheyselinck, J. & Klemenz, R. (1998) J. Immunol. 161, 4866-4874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saga, Y., Tung, J. S., Shen, F. W. & Boyse, E. A. (1986) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83, 6940-6944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruitenberg, E. J. & Elgersma, A. (1976) Nature 264, 258-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kitamura, Y., Go, S. & Hatanaka, K. (1978) Blood 52, 447-452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirshenbaum, A. S., Goff, J. P., Semere, T., Foster, B., Scott, L. M. & Metcalfe, D. D. (1999) Blood 94, 2333-2342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abonia, J. P., Austen, K. F., Rollins, B. J., Joshi, S. K., Flavell, R. A., Kuziel, W. A., Koni, P. A. & Gurish, M. F. (2005) Blood 105, 4308-4313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zon, L. I., Yamaguchi, Y., Yee, K., Albee, E. A., Kimura, A., Bennett, J. C., Orkin, S. H. & Ackerman, S. J. (1993) Blood 81, 3234-3241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walsh, J. C., DeKoter, R. P., Lee, H. J., Smith, E. D., Lancki, D. W., Gurish, M. F., Friend, D. S., Stevens, R. L., Anastasi, J. & Singh, H. (2002) Immunity 17, 665-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stechschulte, D. J., Sharma, R., Dileepan, K. N., Simpson, K. M., Aggarwal, N., Clancy, J., Jr., & Jilka, R. L. (1987) J. Cell. Physiol. 132, 565-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Falcone, F. H., Haas, H. & Gibbs, B. F. (2000) Blood 96, 4028-4038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buhring, H. J., Simmons, P. J., Pudney, M., Muller, R., Jarrossay, D., van Agthoven, A., Willheim, M., Brugger, W., Valent, P. & Kanz, L. (1999) Blood 94, 2343-2356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li, L., Li, Y., Reddel, S. W., Cherrian, M., Friend, D. S., Stevens, R. L. & Krilis, S. A. (1998) J. Immunol. 161, 5079-5086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen, C. C., Grimbaldeston, M. A., Tsai, M., Weissman, I. L. & Galli, S. J. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 11408-11413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jamur, M. C., Grodzki, A. C., Berenstein, E. H., Hamawy, M. M., Siraganian, R. P. & Oliver, C. (2005) Blood 105, 4282-4289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morrison, S. J., Hemmati, H. D., Wandycz, A. M. & Weissman, I. L. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 10302-10306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pennock, J. L. & Grencis, R. K. (2004) Blood 103, 2655-2660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dahl, R., Walsh, J. C., Lancki, D., Laslo, P., Iyer, S. R., Singh, H. & Simon, M. C. (2003) Nat. Immunol. 4, 1029-1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]