Abstract

Human cytomegalovirus replicates in many different cell types, including epithelial cells, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts. However, laboratory strains of the virus, many of which were developed as attenuated vaccine candidates by serial passage in fibroblasts, have lost the ability to infect epithelial and endothelial cells. Their growth is restricted primarily to fibroblasts, due to mutations in the UL131-UL128 locus. We now demonstrate that two products of this locus, pUL130 and pUL128, form a complex with gH and gL, but not gO. The AD169 laboratory strain, which lacks a functional UL131 protein, produces virions containing only the gH-gL-gO complex. An epithelial and endothelial cell tropic AD169 variant in which the UL131 ORF has been repaired, termed BADrUL131, produces virions that carry both gH-gL-gO and gH-gL-pUL128-pUL130 complexes. Antibodies against pUL130 and pUL128 block infection of epithelial and endothelial cells by BADrUL131 and the fusion-inducing factor X clinical human cytomegalovirus isolate but do not affect the efficiency with which fibroblasts are infected.

Keywords: glycoprotein complex, host range

In immunocompromised individuals, human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) infects multiple organ systems, replicating in all major cell types (1). Although clinical isolates replicate in a variety of cell types, laboratory strains, such as AD169 (2) and Towne (3), replicate almost exclusively in fibroblasts (4-10). The restriction in tropism, which results from serial passage of the virus in fibroblasts, is a marker of attenuation (11). Mutations causing the loss of epithelial cell, endothelial cell, polymorphonuclear leukocyte, and dendritic cell tropism in HCMV laboratory strains have been mapped to three ORFs: UL128, UL130, and UL131 (5, 10, 12). Mutation of any one of these ORFs in the FIX clinical isolate of HCMV blocked endothelial cell tropism (5), and repair of a single-nucleotide insertion in the UL131 ORF restored the ability of AD169 to infect endothelial and epithelial cells (10).

Three lines of evidence suggest that the UL131-UL128 proteins are involved in membrane fusion. First, the UL131-UL128 locus mediates the transmission of virus from endothelial cells to leukocytes (5), and the transfer is carried out by transient fusion of plasma membrane patches (13). Second, repair of the defective UL131 ORF in AD169 not only restored its ability to infect endothelial and epithelial cells but also enabled the virus to induce syncyntia (10). Third, pUL130 was recently reported to be in virions (14).

Because the UL131-UL128 locus is not sufficient to induce membrane fusion (our unpublished data), we hypothesized that its products might function in cooperation with one or more virus-coded fusogenic glycoproteins. HCMV particles contain three major glycoprotein complexes (15), all of which are required for HCMV infectivity (16-18). The gCI complex includes two molecules of the UL55-coded gB (15, 19, 20). Each 160-kDa monomer is cleaved (21, 22) to generate a 116-kDa surface unit linked by disulfide bonds to a 55-kDa transmembrane component. Some antibodies to gB inhibit the attachment of virions to cells, whereas others block the fusion of infected cells (19, 23-26), suggesting that the protein might execute multiple functions at the start of infection. Several cellular membrane proteins interact with gB (27-29), and these interactions likely facilitate entry and activate cellular signaling pathways. The gCII complex contains the UL100-coded gM and UL73-coded gN (30, 31), and it is the most abundant of the glycoprotein complexes (32). The complex binds to heparan sulfate proteoglycans, suggesting it might contribute to the initial interaction of the virion with the cell surface (33). It also could perform a structural role during virion assembly/envelopment, similar to the gM-gN complex found in some α-herpesviruses (34). The gCIII complex is comprised of UL75-coded gH, UL115-coded gL, and UL74-coded gO (15, 35-38). All known herpesviruses encode gH-gL heterodimers (39), which mediate fusion of the virion envelope with the cell membrane. Antibodies to HCMV gH do not affect virus attachment but block penetration and cell-to-cell spread (40, 41). Expression of gH-gL in the absence of infection was sufficient to induce syncytia, and inclusion of gO in the assay did not enhance or block the fusion (42). A gO-deficient mutant of AD169 shows a significant growth defect (18). Recently, it was reported that gH binds to integrin αvβ3 (43).

We report here that pUL128 and pUL130 form a complex with gH/gL that is incorporated into virions. Clinical HCMV isolates produce virions containing two gH-gL complexes; one includes gO, and the other includes pUL128-pUL130. The gH-gL-pUL128-pUL130 complex is required to infect endothelial and epithelial cells but not fibroblasts.

Materials and Methods

Biological Materials. Human MRC-5 embryonic lung fibroblasts and ARPE-19 retinal pigmented epithelial cells (American Type Culture Collection) were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS or DMEM/Ham's F-12 medium (1:1) with 10% FBS, respectively, and both cell types were used at passage 24-30. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were obtained by collagenase digestion of umbilical veins grown on gelatin-coated plates in RPMI medium 1640 with 10% FBS, endothelial cell growth supplements (50 μg/ml, Biomedical Technologies, Stroughton, MA) and heparin (75 μg/ml) and used at passage 3-6. HUVECs were maintained without endothelial growth supplements or heparin during virus adsorption and after infection. Human foreskin fibroblasts at passage 10-15 were grown in DMEM with 10% newborn calf serum.

The AD169 strain of HCMV (2) contains a frame-shift mutation in UL131 (44, 45). BADwt (10, 46) is produced from a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clone of AD169. BADrUL131 (10) is a derivative of BADwt in which the UL131 mutation has been repaired so that the ORF is identical to that in the TR HCMV clinical isolate (47). BADdlUL131-128 is a derivative of BADwt that was constructed by replacing the UL131-UL128 locus, base pairs 174865-176806 (44), with a marker cassette containing kanamycin resistance and LacZ genes by using linear recombination (48, 49). The BAC-cloned derivative of the VR1814 clinical isolate of HCMV (50) is termed FIX (51), and we term virus reconstituted from that clone BFXwt. Virus was prepared by electroporation of BAC DNAs into fibroblasts, and the first passage of the virus was used in this study. Virions were partially purified by centrifugation through a sorbitol cushion for use as virus stocks.

Anti-gB 7-17 (52), anti-gM IMP91-3/1 (30), and anti-gH 14-4b (53) and AP86 (54) monoclonal antibodies were gifts from W. Britt (University of Alabama, Birmingham), and rabbit polyclonal anti-gO antibody (35) was a gift from T. Compton (University of Wisconsin, Madison). Murine monoclonal antibodies specific for pUL130 (3E3 and 3C5) and pUL128 (4B10), as well as rabbit anti-pUL128 polyclonal antibody (R551A), were generated by using GST fusion proteins as immunogens.

Protein Analysis. For pulse-chase analysis, MRC-5 cells were held for 1 h in medium lacking methionine and cysteine at 72 h after infection at a multiplicity of three plaque-forming units per cell; 200 μCi/ml (1 Ci = 37 GBq) of 35S Express Protein Labeling Mix (PerkinElmer) was added for 1 h, and then the radioactivity was removed and cells were maintained for 20 or 120 min in medium with excess unlabeled methionine and cysteine plus 10% FBS. Cells were harvested and lysed in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4/150 mM NaCl/1 mM EDTA/1% Nonidet P-40/0.1% SDS/0.5% deoxycholate) containing protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis).

Before immunoprecipitation, lysates were incubated with preimmune mouse or rabbit serum overnight at 4°C and then precleared with protein A Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia Biosciences) or protein G-agarose (Roche Applied Science) to remove proteins that interact nonspecifically with the beads. Antibodies were added to the precleared lysates, incubated overnight at 4°C, and then protein A Sepharose or protein G-agarose was added for 4 h at 4°C. Immune complexes were collected by centrifugation, washed with RIPA buffer, suspended in reducing sample buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 6.8/10% glycerol/2% SDS/1% 2-mercaptoethanol), boiled for 5 min, and proteins were separated by electrophoresis in SDS-containing polyacrylamide gels. The gM-gN complex was assayed by electrophoresis in urea-containing polyacrylamide gels (30). Sequential immunoprecipitations were conducted as described (55).

For analysis of virion proteins, virions were separated from noninfectious particles by centrifugation through glycerol-tartrate gradients (56-58). The purified virions were boiled in reducing or nonreducing sample buffer, and proteins were analyzed by Western blot assay.

Neutralization Assay. Anti-pUL130 monoclonal antibodies were purified by affinity chromatography on protein G-agarose. To purify rabbit anti-pUL128 polyclonal antibody, antiserum was first passed through GST-conjugated Sepharose to deplete anti-GST antibodies that resulted from the use of a pUL128-GST fusion protein as immunogen, followed by affinity purification on protein A Sepharose. Neutralization of BADrUL131 was quantified by plaque-reduction assay. Purified antibodies were diluted in DMEM with 5% complement-inactivated FBS and mixed with an equal volume of virus; after 1 h at room temperature 300-μl aliquots (100 plaque-forming units) were used to infect cell monolayers; after adsorption, the inoculum was removed, and cells were overlaid with medium containing 1% agarose; foci of GFP-expressing cells were counted 2-3 weeks later. Neutralization of FIX virus was quantified by using a microneutralization assay (59).

Results

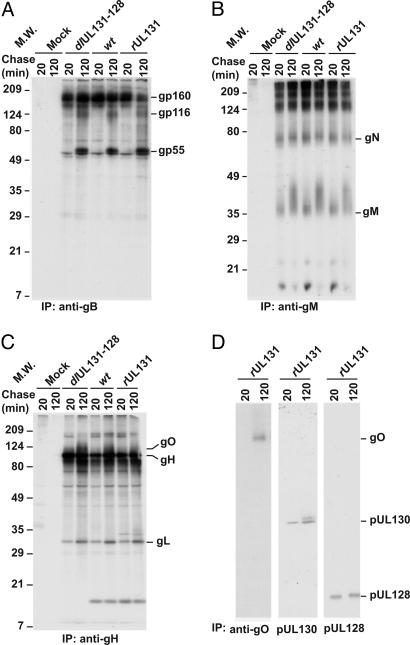

pUL128 and pUL130 Are Present in a Complex with gH. Products of the UL131-128 locus are required for HCMV replication in endothelial and epithelial cells (5, 10). To test the idea that proteins encoded by this locus might function in cooperation with one or more virus-coded fusogenic glycoproteins, we searched for UL131-UL128-coded proteins in virion glycoprotein complexes. Fibroblasts were infected with three viruses: BADwt, an isolate of the AD169 strain of HCMV with a nonfunctional UL131 ORF; BADdlUL131-128, a derivative of BADwt that lacks the UL131-UL128 locus; and BADrUL131, a derivative of BADwt with a repaired UL131 ORF (10). At 72 h postinfection, cells were treated for 1 h with 35S-labeled methionine and cysteine, the label was chased for 20 or 120 min, and then viral glycoprotein complexes were examined by immunoprecipitation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

pUL128 and pUL130 form a complex with gH. MRC-5 cells were infected with BADdlUL131-128, BADwt, or BADrUL131. Seventy-two hours later, cells were radioactively labeled for 1 h and chased for 20 or 120 min. Proteins were immunoprecipitated (IP) from cell lysates and analyzed by electrophoresis in an SDS-containing 12% polyacrylamide gel followed by autoradiography. Immunoprecipitations used anti-gB 7-17 (A), anti-gM IMP91-3/1 (B), anti-gH 14-4b (C), or anti-gH 14-4b, followed by anti-gO, anti-pUL130 3C5, or anti-pUL128 R551A (D). The positions at which marker proteins migrated are identified by their molecular weights (MW).

Consistent with previous reports (20, 22, 53), gB was synthesized and glycosylated to produce a 160-kDa protein at 20 min postlabeling, and it was partially cleaved by 120 min to generate the mature gp55-gp116 gB complex (Fig. 1 A). The gM molecule was synthesized as a protein with an apparent molecular weight of 38 kDa, and it was modified by 120 min after its synthesis to migrate as a diffuse 38- to 46-kDa band (30) (Fig. 1B). The ≈60-kDa protein that coprecipitated with gM was previously identified as gN (30). No differences in gB or gM-gN were observed among the AD169 variants.

In contrast, gH immunoprecipitates revealed distinct complexes after infection with the different viruses (Fig. 1C). As described (36, 55), gL and gO coprecipitated with gH from fibroblasts infected with all three viruses. In addition, a 16-kDa protein was coprecipitated from extracts of BADwt- and BADrUL131-infected cells but not from cells infected with BADdlUL131-128. Also, a 33-kDa protein (20 min) and a 33-plus 35-kDa doublet (120 min) were detected in the BADrUL131 gH coprecipitate. Based on their apparent sizes, we suspected that the 16- and 33- to 35-kDa proteins were pUL128 and pUL130. We therefore performed sequential immunoprecipitation assays in which the gH coprecipitating proteins from BADrUL131-infected lysates were reprecipitated with anti-pUL130 or -pUL128 antibodies (Fig. 1D Center and Right). The 33- to 35- and 16-kDa proteins were specifically precipitated with these antibodies, confirming their identities as pUL130 and pUL128. Antibody to gH also coprecipitated gO from the BADrUL131 lysates (Fig. 1D Left).

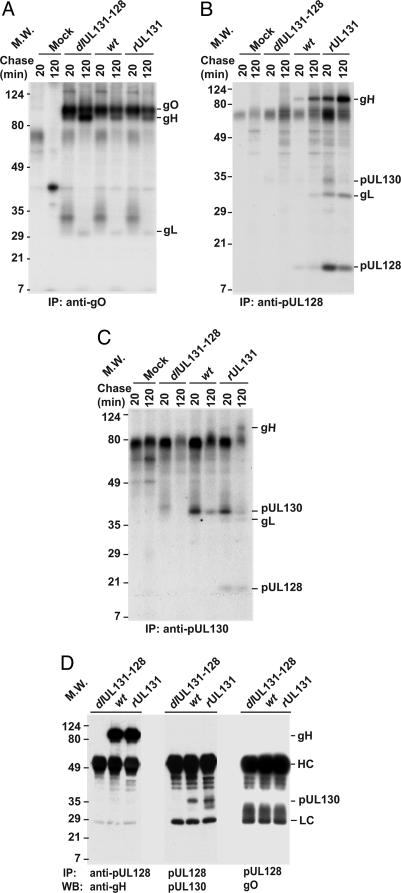

pUL128-pUL130 and gO Form Separate Complexes with gH. To further verify the gH interactions, we performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments using a gO-specific antibody (Fig. 2A). This antibody, like the gH antibody, captures the gH-gL-gO complex (55), and the three components were evident in the immunoprecipitates. Neither pUL128 nor pUL130 was coprecipitated at a detectable level with the gO antibody, suggesting that gO and pUL128-pUL130 form separate complexes with gH. Consistent with this interpretation, the pUL128-specific antibody precipitated gH, gL, and pUL130 from BADrUL131 lysates, but gO was not detected (Fig. 2B). In addition, anti-pUL130 antibody precipitated gH, gL, and pUL128 from BADrUL131-infected cell lysates, but not gO (Fig. 2C). The identities of gH and pUL130 in the anti-pUL128 immunoprecipitate were confirmed by performing Western blot assays, and once again we did not detect gO (Fig. 2D). Our data argue that pUL128-pUL130 and gO form separate complexes with gH.

Fig. 2.

pUL128-pUL130 and gO form separate complexes with gH. MRC-5 cells were infected with BADdlUL131-128, BADwt, or BADrUL131. (A-C) Cells were radioactively labeled for 1 h and chased for 20 or 120 min beginning at 72 h postinfection. Proteins were immunoprecipitated (IP) from cell lysates and analyzed by electrophoresis in an SDS-containing 12% polyacrylamide gel followed by autoradiography. Immunoprecipitations used anti-gO (A), anti-pUL128 4B10 (B), or anti-pUL130 3E3 (C). (D) Displays combined immunoprecipitation and Western blot (WB) assays of pUL128-interacting proteins. Cells were lysed at 72 h postinfection, and extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-pUL128 R551A antibody. The precipitated proteins were separated by electrophoresis in SDS-containing 12% polyacrylamide gels and analyzed by Western blot assay with anti-gH AP86, anti-pUL130 3C3, or anti-gO antibody. The positions at which marker proteins migrated are identified by their molecular weights (MW); antibody heavy (HC) and light chains (LC) are designated.

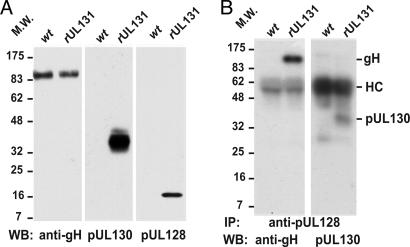

pUL128 and pUL130 Are Present in Virions. Because pUL128 and pUL130 are associated with gH in infected cells, the complex might be incorporated into virions. To test this possibility, purified BADwt and BADrUL131 virions were assayed by Western blot for gH, pUL128, and pUL130 (Fig. 3A). As expected, gH was present in both virion preparations. BADrUL131 but not BADwt virions contained pUL130, consistent with the failure of pUL130 to interact with gH in a BADwt-infected cell lysate (Fig. 1C). Surprisingly, pUL128 also was present only in BADrUL131 virions, even though it interacted with gH independently of pUL130 and pUL131 within extracts of BADwt-infected cells (Fig. 1C). We interpret this to indicate that only a complete gH-gL-pUL130-pUL128 complex is incorporated into virions.

Fig. 3.

pUL128 and pUL130 are in virions. (A) BADwt and BADrUL131 virion proteins were analyzed by Western blot (WB) by using anti-gH AP86, anti-pUL130 3C5, or anti-pUL128 4B10 antibody. (B) Virion proteins were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-pUL128 R551A and analyzed by Western blot by using anti-gH AP86 or anti-pUL130 3C5 antibody. The positions at which marker proteins migrated are identified by their molecular weights (MW); antibody heavy chains (HC) are designated.

To ascertain that pUL128 associates with gH in virions, BADrUL131 virion proteins were immunoprecipitated with pUL128-specific antibody and analyzed by Western blot with anti-gH or -pUL130 antibody (Fig. 3B). Both gH and pUL130 proteins were captured with anti-pUL128 antibody, confirming that the three proteins are complexed in virions as in cell extracts.

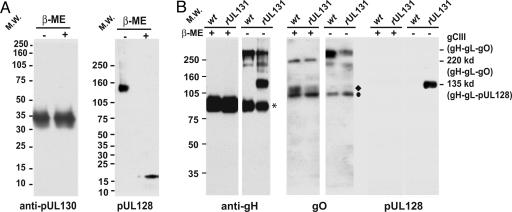

Characterization of gH Complexes. Disulfide bonds link gH to gO and gL (15, 35, 55, 60). We tested the possibility that gH interacts with pUL128 and pUL130 in the same manner. BADrUL131 virion proteins were resolved by electrophoresis in reducing or nonreducing gels, transferred to membranes, and probed with anti-pUL130 or -pUL128 antibodies. As shown in Fig. 4A Left, the reducing agent did not change the mobility of pUL130, suggesting that it is not linked to other proteins through disulfide bonds. In contrast, in the absence of 2-mercaptoethanol treatment, the anti-pUL128 antibody recognized a 135-kDa protein, and treatment with the reducing agent released monomeric pUL128 (Fig. 4A Right). The complex presumably includes gH and gL in addition to pUL128, because both gH and gL were precipitated from extracts of infected cells with pUL128-specific antibody (Fig. 2B). Its 135-kDa size is consistent with the interpretation that it contains one molecule each of gH (86 kDa), gL (31 kDa), and pUL128 (16 kDa).

Fig. 4.

Characterization of gH-gL complexes. (A) Disulfide linkage of pUL128 with gH-gL. Purified BADrUL131 proteins in buffer with or without 2-mercaptoethanol (β-ME) were subjected to electrophoresis in an SDS-containing 12% (Left) or 4-20% (Right) polyacrylamide gel and analyzed by Western blot (WB) by using anti-pUL130 3C5 (Left) or anti-pUL128 4B10 (Right) antibody. (B) Comparison of complexes in BADwt and BADrUL131 virions. Virion proteins were separated by electrophoresis in SDS-containing, reducing or nonreducing, 8% polyacrylamide gels and analyzed by Western blot (WB) assay by using anti-gO (Left), anti-gH AP86 (Center), or anti-pUL128 4B10 (Right) antibody. *, monomeric gH; ♦ and • identify monomeric forms of gO. The positions at which marker proteins migrated are identified by their molecular weights (MW).

Because pUL128 and gO form separate disulfide-bonded complexes with gH, we next compared the gH-gL-gO and gH-gL-pUL128 complexes present in BADwt versus BADrUL131 virions. Under reducing conditions (Fig. 4B Left, +2-mercaptoethanol), only monomeric, 86-kDa gH was observed. However, in the absence of reducing agent, more slowly migrating bands were evident (Fig. 4B Left, -2 -mercaptoethanol), which presumably represented disulfide-bonded complexes. In BADwt, major gH-containing complexes migrated at 300 and 220 kDa. The 220-kDa moiety was previously shown to be a partially modified gH-gL-gO complex (55), and the 300-kDa moiety corresponds to the mature gH-gL-gO (gCIII) complex (35, 55, 60). An additional gH-containing complex was present in BADrUL131 but not BADwt virions. It migrated with an apparent molecular weight of 135 kDa, the same mobility as the complex recognized by antibody to pUL128 (Fig. 4A), suggesting that it might be a gH-gL-pUL128 complex. Consistent with earlier reports (36), monomeric gH was observed in the absence of reducing agent in virions, indicating that a portion of it is not covalently bonded to other glycoproteins.

We performed additional Western blot assays on the same set of virion samples. As anticipated, gO-specific antibody recognized the 300- and 220-kDa complexes but not the 135-kDa complex (Fig. 4B Center). In contrast, the anti-pUL128 antibody reacted with the 135-kDa moiety but not the larger complexes (Fig. 4B Right). We conclude that two gH complexes are in BADrUL131 virions: gH-gL-pUL128-pUL130 and gH-gL-gO. BADwt virions contain only one gH complex, gH-gL-gO.

pUL128 and pUL130 Antibodies Block Infection of Epithelial and Endothelial Cells. BADrUL131 virions, which contain the gH-gL-pUL128-pUL130 complex, can efficiently infect endothelial cells, epithelial cells, and fibroblasts (10). BADwt, which lacks the complex, is restricted to fibroblasts. Accordingly, we performed neutralization assays to test the idea that this complex is required to infect epithelial or endothelial cells. Affinity-purified antibodies were used, and no complement was added to the assays. As shown in Fig. 5A, pUL130-specific 3E3 monoclonal antibody inhibited BADrUL131 infection of ARPE-19 or HUVEC cells but not MRC-5 cells. Fifty percent neutralization was achieved at ≈20 μg/ml antibody. The 3C5 antibody, which recognizes a different pUL130 epitope (data not shown), did not block infection. Rabbit polyclonal antibody to pUL128 also neutralized the ability of BADrUL131 to infect ARPE-19 and HUVEC cells but not MRC-5 cells. The patterns of inhibition were the same for endothelial and epithelial cells, suggesting that BADrUL131 utilizes the same mechanism to infect the two cell types. The antibody to pUL128 also blocked infection of ARPE-19 and HUVEC cells by the BFXwt clinical strain of HCMV and again did not notably inhibit infection of MRC-5 cells (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Neutralization of HCMV infectivity ARPE-19 epithelial cells, HUVEC endothelial cells, and MRC-5 fibroblasts. BADrUL131 (A)orBFXwt (B) were incubated with various concentrations of anti-pUL130 3C5 or 3E3 or anti-pUL128 R551A antibody, and residual infectivity was determined on different cell types.

Discussion

Earlier work demonstrated that the UL131-UL128 locus is a primary determinant of HCMV cell host range (5, 10). Now we have determined that pUL128 and pUL130 are present in a complex with gH and gL (Fig. 1, 2, 3, 4). Glycoprotein H is a component of the viral membrane fusion machinery that facilitates viral entry (41, 61, 62), and gL may function as a chaperone-like protein, targeting gH to the cell surface (63). By complexing with gH-gL, pUL128 and pUL130 likely participate in the entry of HCMV into epithelial and endothelial cells. Consistent with this interpretation, antibodies to either protein neutralized the ability of HCMV to infect endothelial or epithelial cells, but not fibroblasts (Fig. 5).

The function of pUL131 is not clear. We anticipated that all three proteins encoded by the UL130-UL128 locus would form a complex, because mutations in any of the three ORFs can abolish epithelial and endothelial cell tropism (5, 10). However, we did not observe a band potentially corresponding to pUL131 after immunoprecipitation with antibodies to gH (Fig. 1) or pUL128 (Fig. 2). It is conceivable that pUL131 is part of the complex, but its association is not stable to the sample preparation conditions that we used. Alternatively, pUL131 might not be a component of the complex but might serve to stabilize pUL130 or deliver pUL130 to the gH-gL-pUL128 complex, because pUL130 was not detectably incorporated into the complex in pUL131-deficient BADwt-infected fibroblasts (Fig. 1C). It also could play a role in the incorporation of the complex into virions, because the gH-gL-pUL128 complex accumulates in BADwt-infected cells (Fig. 1C) but is not incorporated into virions (Fig. 3).

Two distinct gH complexes were found in BADrUL131 virions: gH-gL-pUL128-pUL130 and gH-gL-gO (Figs. 3 and 4B). In contrast, BADwt virions contain only the gH-gL-gO complex. The different complexes likely form the basis for the host range differences between the two viruses. We propose that, whereas the gH-gL-gO complex is sufficient to mediate infection of fibroblasts, the gH-gL-pUL128-pUL130 complex is required to infect epithelial and endothelial cells.

The HCMV gH complexes resemble the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and human herpesvirus 6A (HHV-6A) gH complexes. Like HCMV, EBV virions contain two gH complexes: gH-gL and gH-gL-gp42 (64, 65). EBV uses different gH and gL complexes to infect B and epithelial cells (66). Fusion with B cells is mediated by the gH-gL-gp42 complex, which binds to cell surface HLA class II (67-69). In contrast, entry into an epithelial cell does not require gp42 but does require interaction of the gH-gL complex with an unknown receptor (64, 66, 70). HHV-6A also produces two gH complexes: gH-gL-gO (71) and gH-gL-gQ1-gQ2 (72). The HHV-6A gH-gL-gQ1-gQ2 complex serves as a viral ligand for the entry receptor, CD46 (73-75). HHV-6A, but not HHV-6B, mediates fusion in a variety of cells expressing CD46 (73). The presence of gH-gL-gQ1-gQ2 on the virion envelope or sequence divergence of its constituents might be responsible for differences in host cell tropism between HHV-6A and -6B (76).

Acknowledgments

We thank W. Britt (University of Alabama, Birmingham) and T. Compton (University of Wisconsin, Madison) for generous gifts of antibodies. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants CA85786, CA82396, AI54430, and GM71508.

Author contributions: D.W. and T.S. designed research; D.W. performed research; D.W. and T.S. analyzed data; and D.W. and T.S. wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

Abbreviations: HCMV, human cytomegalovirus; HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; HHV-6A, human herpesvirus 6A.

References

- 1.Plachter, B., Sinzger, C. & Jahn, G. (1996) Adv. Virus Res. 46, 195-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elek, S. D. & Stern, H. (1974) Lancet 1, 1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plotkin, S. A., Furukawa, T., Zygraich, N. & Huygelen, C. (1975) Infect. Immun. 12, 521-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman, H. M., Macarak, E. J., MacGregor, R. R., Wolfe, J. & Kefalides, N. A. (1981) J. Infect. Dis. 143, 266-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hahn, G., Revello, M. G., Patrone, M., Percivalle, E., Campanini, G., Sarasini, A., Wagner, M., Gallina, A., Milanesi, G., Koszinowski, U., et al. (2004) J. Virol. 78, 10023-10033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho, D. D., Rota, T. R., Andrews, C. A. & Hirsch, M. S. (1984) J. Infect. Dis. 150, 956-957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacCormac, L. P. & Grundy, J. E. (1999) J. Med. Virol. 57, 298-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinzger, C., Schmidt, K., Knapp, J., Kahl, M., Beck, R., Waldman, J., Hebart, H., Einsele, H. & Jahn, G. (1999) J. Gen. Virol. 80, 2867-2877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vonka, V., Anisimova, E. & Macek, M. (1976) Arch. Virol. 52, 283-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang, D. & Shenk, T. (2005) J. Virol. 79, 10330-10338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerna, G., Percivalle, E., Baldanti, F. & Revello, M. G. (2002) J. Med. Virol. 66, 335-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerna, G., Percivalle, E., Lilleri, D., Lozza, L., Fornara, C., Hahn, G., Baldanti, F. & Revello, M. G. (2005) J. Gen. Virol. 86, 275-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerna, G., Percivalle, E., Baldanti, F., Sozzani, S., Lanzarini, P., Genini, E., Lilleri, D. & Revello, M. G. (2000) J. Virol. 74, 5629-5638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patrone, M., Secchi, M., Fiorina, L., Ierardi, M., Milanesi, G. & Gallina, A. (2005) J. Virol. 79, 8361-8373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gretch, D. R., Kari, B., Rasmussen, L., Gehrz, R. C. & Stinski, M. F. (1988) J. Virol. 62, 875-881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunn, W., Chou, C., Li, H., Hai, R., Patterson, D., Stolc, V., Zhu, H. & Liu, F. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 14223-14228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu, D., Silva, M. C. & Shenk, T. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 12396-12401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hobom, U., Brune, W., Messerle, M., Hahn, G. & Koszinowski, U. H. (2000) J. Virol. 74, 7720-7729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cranage, M. P., Kouzarides, T., Bankier, A. T., Satchwell, S., Weston, K., Tomlinson, P., Barrell, B., Hart, H., Bell, S. E., Minson, A. C., et al. (1986) EMBO J. 5, 3057-3063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gretch, D. R., Gehrz, R. C. & Stinski, M. F. (1988) J. Gen. Virol. 69, 1205-1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spaete, R. R., Thayer, R. M., Probert, W. S., Masiarz, F. R., Chamberlain, S. H., Rasmussen, L., Merigan, T. C. & Pachl, C. (1988) Virology 167, 207-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Britt, W. J. & Vugler, L. G. (1989) J. Virol. 63, 403-410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Navarro, D., Paz, P., Tugizov, S., Topp, K., La Vail, J. & Pereira, L. (1993) Virology 197, 143-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohizumi, Y., Suzuki, H., Matsumoto, Y., Masuho, Y. & Numazaki, Y. (1992) J. Gen. Virol. 73, 2705-2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gicklhorn, D., Eickmann, M., Meyer, G., Ohlin, M. & Radsak, K. (2003) J. Gen. Virol. 84, 1859-1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Britt, W. J., Vugler, L. & Stephens, E. B. (1988) J. Virol. 62, 3309-3318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang, X., Huong, S. M., Chiu, M. L., Raab-Traub, N. & Huang, E. S. (2003) Nature 424, 456-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Compton, T., Kurt-Jones, E. A., Boehme, K. W., Belko, J., Latz, E., Golenbock, D. T. & Finberg, R. W. (2003) J. Virol. 77, 4588-4596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feire, A. L., Koss, H. & Compton, T. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 15470-15475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mach, M., Kropff, B., Dal Monte, P. & Britt, W. (2000) J. Virol. 74, 11881-11892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kari, B., Li, W., Cooper, J., Goertz, R. & Radeke, B. (1994) J. Gen. Virol. 75, 3081-3086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Varnum, S. M., Streblow, D. N., Monroe, M. E., Smith, P., Auberry, K. J., Pasa-Tolic, L., Wang, D., Camp, D. G., 2nd, Rodland, K., Wiley, S., et al. (2004) J. Virol. 78, 10960-10966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kari, B. & Gehrz, R. (1992) J. Virol. 66, 1761-1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brack, A. R., Dijkstra, J. M., Granzow, H., Klupp, B. G. & Mettenleiter, T. C. (1999) J. Virol. 73, 5364-5372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huber, M. T. & Compton, T. (1998) J. Virol. 72, 8191-8197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li, L., Nelson, J. A. & Britt, W. J. (1997) J. Virol. 71, 3090-3097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cranage, M. P., Smith, G. L., Bell, S. E., Hart, H., Brown, C., Bankier, A. T., Tomlinson, P., Barrell, B. G. & Minson, T. C. (1988) J. Virol. 62, 1416-1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaye, J. F., Gompels, U. A. & Minson, A. C. (1992) J. Gen. Virol. 73, 2693-2698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spear, P. G. & Longnecker, R. (2003) J. Virol. 77, 10179-10185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rasmussen, L. E., Nelson, R. M., Kelsall, D. C. & Merigan, T. C. (1984) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81, 876-880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keay, S. & Baldwin, B. (1991) J. Virol. 65, 5124-5128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kinzler, E. R. & Compton, T. (2005) J. Virol. 79, 7827-7837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang, X., Huang, D. Y., Huong, S. M. & Huang, E. S. (2005) Nat. Med. 11, 515-521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chee, M. S., Bankier, A. T., Beck, S., Bohni, R., Brown, C. M., Cerny, R., Horsnell, T., Hutchison, C. A., 3rd, Kouzarides, T., Martignetti, J. A., et al. (1990) Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 154, 125-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Akter, P., Cunningham, C., McSharry, B. P., Dolan, A., Addison, C., Dargan, D. J., Hassan-Walker, A. F., Emery, V. C., Griffiths, P. D., Wilkinson, G. W., et al. (2003) J. Gen. Virol. 84, 1117-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu, D., Smith, G. A., Enquist, L. W. & Shenk, T. (2002) J. Virol. 76, 2316-2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murphy, E., Yu, D., Grimwood, J., Schmutz, J., Dickson, M., Jarvis, M. A., Hahn, G., Nelson, J. A., Myers, R. M. & Shenk, T. E. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 14976-14981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu, D., Ellis, H. M., Lee, E. C., Jenkins, N. A., Copeland, N. G. & Court, D. L. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 5978-5983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang, D., Bresnahan, W. & Shenk, T. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 16642-16647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grazia Revello, M., Baldanti, F., Percivalle, E., Sarasini, A., De-Giuli, L., Genini, E., Lilleri, D., Labo, N. & Gerna, G. (2001) J. Gen. Virol. 82, 1429-1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hahn, G., Khan, H., Baldanti, F., Koszinowski, U. H., Revello, M. G. & Gerna, G. (2002) J. Virol. 76, 9551-9555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Britt, W. J. (1984) Virology 135, 369-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Britt, W. J., Vugler, L., Butfiloski, E. J. & Stephens, E. B. (1990) J. Virol. 64, 1079-1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Urban, M., Britt, W. & Mach, M. (1992) J. Virol. 66, 1303-1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huber, M. T. & Compton, T. (1999) J. Virol. 73, 3886-3892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baldick, C. J., Jr., & Shenk, T. (1996) J. Virol. 70, 6097-6105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Irmiere, A. & Gibson, W. (1985) J. Virol. 56, 277-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Talbot, P. & Almeida, J. D. (1977) J. Gen. Virol. 36, 345-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Andreoni, M., Faircloth, M., Vugler, L. & Britt, W. J. (1989) J. Virol. Methods 23, 157-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huber, M. T. & Compton, T. (1997) J. Virol. 71, 5391-5398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Milne, R. S., Paterson, D. A. & Booth, J. C. (1998) J. Gen. Virol. 79, 855-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Keay, S. & Baldwin, B. R. (1996) J. Gen. Virol. 77, 2597-2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Spaete, R. R., Perot, K., Scott, P. I., Nelson, J. A., Stinski, M. F. & Pachl, C. (1993) Virology 193, 853-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li, Q., Turk, S. M. & Hutt-Fletcher, L. M. (1995) J. Virol. 69, 3987-3994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hutt-Fletcher, L. M. & Lake, C. M. (2001) Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 258, 51-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang, X., Kenyon, W. J., Li, Q., Mullberg, J. & Hutt-Fletcher, L. M. (1998) J. Virol. 72, 5552-5558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Haan, K. M., Kwok, W. W., Longnecker, R. & Speck, P. (2000) J. Virol. 74, 2451-2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haan, K. M. & Longnecker, R. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 9252-9257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li, Q., Spriggs, M. K., Kovats, S., Turk, S. M., Comeau, M. R., Nepom, B. & Hutt-Fletcher, L. M. (1997) J. Virol. 71, 4657-4662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang, X. & Hutt-Fletcher, L. M. (1998) J. Virol. 72, 158-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mori, Y., Akkapaiboon, P., Yonemoto, S., Koike, M., Takemoto, M., Sadaoka, T., Sasamoto, Y., Konishi, S., Uchiyama, Y. & Yamanishi, K. (2004) J. Virol. 78, 4609-4616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Akkapaiboon, P., Mori, Y., Sadaoka, T., Yonemoto, S. & Yamanishi, K. (2004) J. Virol. 78, 7969-7983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mori, Y., Seya, T., Huang, H. L., Akkapaiboon, P., Dhepakson, P. & Yamanishi, K. (2002) J. Virol. 76, 6750-6761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mori, Y., Yang, X., Akkapaiboon, P., Okuno, T. & Yamanishi, K. (2003) J. Virol. 77, 4992-4999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Santoro, F., Kennedy, P. E., Locatelli, G., Malnati, M. S., Berger, E. A. & Lusso, P. (1999) Cell 99, 817-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ablashi, D. V., Balachandran, N., Josephs, S. F., Hung, C. L., Krueger, G. R., Kramarsky, B., Salahuddin, S. Z. & Gallo, R. C. (1991) Virology 184, 545-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]