Abstract

The pathways responsible for the rapid and sustained increases in [Ca2+]i following activation of angiotensin II (ANG II) receptors (AT1) in renal vascular smooth muscle cells (RVSMC) were evaluated using fluorescence microscopy. Resting intracellular calcium concentration [Ca2+]i averaged 75 ± 9nM. The response to ANG II (100nM) was characterized by a rapid initial increase of [Ca2+]i by 74 ± 6 nM (n=35) followed by a decrease to a sustained level of 12 ± 2 nM above baseline. The average time from peak to 50% reduction from the peak value (50% time point) was 32 ± 4 seconds. AT1 receptor blockade with 1μM candesartan (n=5) prevented the responses to ANG II. In nominally calcium-free conditions (n=8) the peak increase in [Ca2+]i averaged 42 ± 7 nM but the sustained phase was absent and the 50% time point was reduced to 11 ± 4 seconds. L-type calcium channel blockade with diltiazem reduced the peak [Ca2+]i to 24 ± 8 nM and the sustained level to 4 ± 2 nM (n=10). In cells preincubated in low Cl− (3.0 mM), the peak response to ANG II was suppressed as was the sustained response. Blockade of chloride channels with DIDS eliminated both the peak and sustained responses (n=11); chloride channel blockade with DPC (n=17), suppressed the peak increase in [Ca2+]i to 18 ± 5 and also prevented the sustained response. IP3 receptor blockade by 10μM TMB-8 (n=6) reduced the peak to 22 + 8 and prevented the sustained response. Exposure to 10μTMB-8 in the presence of Ca2+-free medium prevented the ANG II response (n=9). In the presence of 100μM DPC and 10μM TMB-8 (n=7) the ANG II response was also prevented. Thus, the rapid initial increase in [Ca2+]i is due not only to release from intracellular stores, but also to Ca2+ influx from the extracellular fluid. While Ca2+ entry via L-type calcium channels is responsible for the major portion of the sustained response, other entry pathways participate. The finding that chloride channel blockers markedly attenuate both rapid and sustained responses indicates that chloride channel activation contributes to, rather than being the consequence, of the initial rapid response.

Keywords: Preglomerular Smooth Muscle Cell, Calcium Influx, Calcium Mobilization, Fluorescence Cell Microscopy, L-Type Ca2+ Channels, AT1 Receptor Blockers, Diltiazem; DIDS, DPC, Candesartan

Introduction

Angiotensin II (ANG II) is an important regulator of the renal microcirculation, and exerts major actions on afferent and efferent arterioles (1; 5; 16; 23; 24; 26). While it has been clearly demonstrated that ANG II increases intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) in vascular smooth muscle cells (RVSMC), the sequence of events following activation of ANG II type 1 receptors (AT1) remains unclear (6; 13; 29; 32). Typically, the calcium response is characterized by a sharp transient rise in [Ca2+]i. followed by a fall toward a sustained plateau above baseline (13). While the sustained increases in [Ca2+]i are thought to be mediated through Ca2+ influx, the early peak response is generally considered to be due to mobilization of intracellular stores (15–17; 23; 32). AT1 receptor-coupled G-proteins activate PLC, which, in turn, activates IP3 and DAG, leading to release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (26; 32). It has been suggested that the increased [Ca2+]i activates chloride channels (ClCa) causing an efflux of chloride and subsequent depolarization of the cell membrane leading to opening of voltage-gated calcium channels (3; 19; 22; 27; 33; 34). However, the role of chloride channels in afferent arteriolar vasoconstriction remains somewhat controversial. Some reports indicate that chloride channel activation is an important step in mediating the afferent arteriolar constrictor response to ANG II, whereas other reports fail to support such a role (3; 18; 19; 30; 31; 33–35). Salomonsson et al.2004 (32) outlined the conflicting reports concerning calcium-activated chloride channels and emphasized that the chain of events leading to depolarization and opening of L-type Ca2+ channels is not fully elucidated.

Previous studies evaluating afferent arteriolar diameters and intracellular calcium concentrations, have demonstrated that L-type calcium channels are critical to the sustained response of preglomerular RVSMC to ANG II (17; 23; 25; 35). L-type calcium channel blockers prevent constriction of afferent arterioles as well as reduce sustained [Ca2+]i increases (5; 26; 29; 35). In addition, removal of extracellular calcium reduces the sustained increase in [Ca2+]i after exposure to ANG II, suggesting the importance of calcium entry in maintaining the elevated intracellular calcium levels (6; 17; 23). Store operated calcium channels potentially play a role in the increase in [Ca2+]i as well, but the temporal relationships related to activation of voltage dependant and store operated channels has not been established (32). Additionally, the cascade of events that determine the magnitude of the peak response as well as the sustained increases in [Ca2+]i have remained controversial and the quantitative contributions of the various processes remain unclear. Accordingly, studies were performed on isolated RVSMC to delineate the contribution of Ca2+ influx, intracellular calcium mobilization and chloride channel activation to the initial peak and the sustained increases in [Ca2+]i that occur following exposure to ANG II.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Preparation and Renal Microvascular Smooth Muscle Cell Isolation

Studies were performed in accordance with the Tulane University Advisory Committee for Animal Resources guidelines. Male Sprague-Dawley CD-VAF rats (200–400g; Charles Rivers Laboratories; Wilmington, MA) were injected IP with the ACE inhibitor enalaprilat (10mg/kg) one hour prior to being anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (40mg/kg). Following anesthesia, the abdominal cavity was exposed via a midline incision and the abdominal aorta was cannulated with ligatures placed above and below the renal arteries. The kidneys were perfused with an ice-cold physiological salt solution (PSS) composed of 0.1mM CaCl2, 125.0mM NaCl, 5.0mM KCl, 1.0mM MgCl2, 10.0mM Glucose, 20.0mM HEPES (100μM Ca2+ PSS) and 6% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and RVSMC were obtained as previously reported (12). After the kidneys were cleared of blood, the solution was switched to a 100μM Ca2+ PSS with 6% BSA and 1% Evan’s Blue. The kidneys were resected, decapsulated, and the renal medullary tissue was removed; the remaining cortical tissue was then pressed through a 180μm mesh sieve. The retained renal tissue was washed with 100μM Ca2+ PSS, and placed into a 15mL Erlenmeyer flask containing 10mL 100μM Ca2+ PSS, 17.5mg of collagenase D (Boehinger Manheim Corp, Indianapolis, IN), 1.3 mM dithiothreitol (Sigma Chemical Co, St. Louis, MO), 15μM BSA, and 10μM soybean trypsin inhibitor (type I-S, Sigma). The flask was placed in a shaking water bath at 37 °C, and digested for 30 minutes while being bubbled with 95% Oxygen/5% Carbon dioxide gas. Vessels were transferred to a 70μm nylon mesh and washed with ice-cold 100μM Ca2+ PSS. Afferent arterioles were identified under the stereoscope: Vascular elements can be clearly discerned both by size and by the number of branches from the parent arteries. Arcuate arteries branch from the major arterial elements and are excluded from the sample. Interlobular arteries can be seen branching from the arcuate arteries and usually give rise to several afferent arterioles, which can also be clearly identified. These interlobular arteries and afferent arterioles are separated from the vascular tree. Afferent arteriolar segments are individually selected for subsequent study. Vessels were placed into a flask containing 15μM BSA in 100μM Ca2+ PSS for ten minutes. Vessels were then transferred to a final digestion solution containing 10μM soybean trypsin inhibitor and 20mg collegenase D and shaken at 37°C for 15 minutes. Vessels were centrifuged at 500g for 5 minutes and resuspended in 1ml DMEM (Sigma) with 20% FCS (Whittaker Bioproducts, Walkerville, MD) containing 10μM FURA-2(AM) (Texas Fluorescence Labs, Austin, TX) and incubated in the dark at room temperature for one hour (13; 14). Solutions were tested for sodium and potassium concentrations by flame spectrophotometry (Instrumentation Laboratory), osmolality (Wescor Co.) and pH and calcium concentrations (Bayer Diagnostics pH/Calcium analyzer).

While we realize that the enzymatic digestion could have undesirable effects, we have optimized the concentrations used in order to yield the preparation required for the studies. Microscopic examination of the cells and their cell membranes revealed clear smooth surfaces and baseline fura 2 fluorescence levels are consistent with those of smooth muscle cells in culture and reported by other groups that use freshly isolated smooth muscle cells. This observation suggests that the membranes are in good condition in our experimental setting because these are studied in a free flowing perfusion chamber. Leaking cell membranes are clearly visible as steadily declining baseline fluorescence during the control period. In addition, the baseline fluorescence consistently yields ratio values less than 1.0 indicating that intracellular calcium levels are low with respect to the extracellular fluid. We retain consistent calcium responses to ATP, AVP, norepinephrine, endothelin, serotonin and 20-HETE.

Calcium Measurements

Aliquots of the suspended cell mixture were mounted in 200μl perfusion chambers (Warner Instruments, Eugene OR) and examined using a Nikon Diaphot inverted microscope with an attached Photon Technology International (PTI) deltascan fluorescence based spectrophotometry system with excitation wavelengths set at 340 and 380 nm and emission collected at 510 nm (13; 14). Cells were continually superfused with a PSS containing 1.8 mM CaCl2 at 35°C. Vessels were isolated in the optical field, and 5 calcium measurements per second were taken with appropriate background elimination. Fluorescence experiments werecalibrated in vitro using the methods described by Grynkiewicz et al. (9).

Experimental Approach

Series 1

Experiments were conducted to evaluate the effects of ANG II in freshly isolated VSMC. In control experiments, calcium fluorescence was measured in vessel fragments exposed to 1.8 mM Ca2+ PSS for 0–100 seconds, followed by 100nM ANG II in 1.8 mM Ca2+ PSS (100–300 seconds) before being returned to the 1.8 mM Ca2+ PSS for a final period (300–500seconds). This concentration of ANG II was selected on the basis of a series of preliminary experiments using concentrations varying from 1 to 500 nM. With 1 and 10 nM ANG II, the responses were less consistent and less reproducible. 500 nM ANG II produced more prolonged responses but not of higher magnitude than with 100 nM ANG II; additionally the highest concentration often caused sufficient cellular contraction to disrupt the attachment of the cells to the slide, which precluded further measurements. Peak change in [Ca2+]i in response to ANG II was determined as the highest [Ca2+]i during ANG II exposure with the baseline average of [Ca2+]i measured during the 5 second period prior to introduction of ANG II subtracted from the maximal response. The time required for the response to reach its maximum, as well as the time interval from the peak response to a 50% reduction in the initial peak values (50% time point) were recorded for all experimental series to determine if the various manipulations altered these temporal patterns. The average of the Ca2+ fluorescence during the last 5 seconds of exposure to ANG II was also used to represent the sustained Ca2+ response to ANG II.

Series 2

Experiments evaluating the effects of the AT1 receptor blocker, candesartan (1μM), were performed to determine the contribution of the AT1 receptors to the response. Cells were exposed to candesartan for 0–100 seconds followed by treatment with 100nM ANG II in the continued presence of candesartan (100–300 seconds). Following exposure to ANG II, the candesartan was continued for an additional 100 seconds before returning to the 1.8 mM Ca2+ PSS (400–500 seconds).

Series 3

Experiments evaluating the effects of the removal of extracellular Ca2+ were performed to determine the magnitude of Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. Cells were exposed to a nominally calcium free PSS for 0–100 seconds followed by treatment with 100nM ANG II in the continued absence of extracellular Ca2+ (100–300 seconds). Following exposure to ANG II, the cells were washed for an additional 100 seconds in the calcium free solution alone (300–400), before being returned to the 1.8 mM Ca2+ PSS solution (400–500 seconds).

To test the possibility that residual Ca2+ in the calcium free solution was responsible for the increase in [Ca2+]i, RVSMC were depolarized with an isotonic solution containing a high concentration of potassium (90mM KCl) in the presence of the nominally calcium free solution (4; 13). Cells were exposed to 1.8mM Ca2+ PSS for 0–100 seconds followed by the introduction of the high KCl solution (100–300 seconds). After confirming that depolarization by the high KCl solution caused an increase in [Ca2+]i, the cells were washed with the calcium free solution (300–500 seconds) and then exposed to the high KCl solution in the absence of extracellular Ca2+. Cells were returned to the calcium containing solution (500–600 seconds) before being challenged a third time with the high KCl in the presence of 1.8 mM Ca2+ (600–800 seconds). This test was performed to determine if the Ca2+ in the nominally calcium free solution was sufficient to account for the increases in [Ca2+]i occurring in response to ANG II during exposure to the calcium free solution. Additionally, residual Ca2+ in the nominally Ca2+-free media was measured using Fura2 K+ salt. 10μM Fura2 K+ salt was added to a sample of the Ca2+-free media and fluorescence measurements were taken and compared to the fluorescence levels of the Rmin and Rmax solutions. 3 separate lots of Ca2+-free media were tested and the average calcium concentration was 38nM.

Series 4

Experiments evaluating the effects of blocking L-type Ca2+ channels with diltiazem (10μM) were performed to determine the contribution of influx of Ca2+ through L-type calcium channels in response to ANG II. Cells were exposed to a PSS containing 10μM diltiazem in the presence of 1.8 mM Ca2+ for 0–100 seconds followed by treatment with 100nM ANG II in the continued presence of diltiazem (100–300 seconds). Following exposure to ANG II, the cells were washed for an additional 100 seconds in the solution containing diltiazem and 1.8 mM Ca2+ PSS (300–400 seconds), before being returned to the 1.8 mM Ca2+ PSS (400–500 seconds). Baseline, peak and sustained changes were calculated as described previously.

Series 5

Experiments evaluating the effect of Cl− channel blockers were performed to determine the contribution of Cl− channel activation in the ANG II responses (19; 22). Cells were exposed to a solution containing 100μM 4,4’-diisothioyanostilbene-2,2’ disulfonic acid (DIDS) in the presence of 1.8 mM Ca2+ PSS for 0–100 seconds, followed by treatment with 100nM ANG II in the continued presence of DIDS (100–300 seconds). Following exposure to ANG II, the cells were washed for an additional 100 seconds in the solution containing DIDS and 1.8 mM Ca2+ PSS (400–500 seconds). A chemically distinct chloride channel blockers, diphenylamine-2-carboxylic acid (DPC) was also used to evaluate the effect of a different chloride channel blocker on the ANG II mediated responses at 100μM and 500μM dosages.

Series 6

Cells were incubated in a 3mM chloride solution in order to deplete intracellular Cl− and study the effects of reduced chloride channel activity without the presence of chemical blockers. Isotonic solutions were prepared using equal concentrations of Na isethionic acid instead of NaCl and K gluconate instead of KCl. Cells were then extracted using the previously described procedure and incubated in the 3mM Cl− solution for one hour while they were being loaded with Fura 2. The cells were then exposed to 100nM ANG II dissolved in the PSS solution containing 140mM Cl− described previously. With this procedure, it would be expected that the electrochemical gradient for chloride efflux would be reduced effectively inhibiting the chloride channels.

Series 7

Experiments evaluating the effect of IP3 receptor blockade were performed to determine the contribution of intracellular mobilization in the ANG II responses. Cells were exposed to a solution containing 8-(diethylamino)-octyl-3,4,5-trimethoxybenzoate (TMB-8) in the presence of 1.8 mM Ca2+ PSS for 50–100 seconds, followed by treatment with 100nM ANG II in the continued presence of TMB-8 (100–300 seconds). Following exposure to ANG II, the cells were washed for an additional 100 seconds in the solution containing TMB-8 and 1.8 mM Ca2+ PSS (300–400 seconds). Experiments evaluating the effect of IP3 receptor blockade in the presence of Ca2+-free media were performed. Cells were exposed to a solution containing TMB-8 in the presence of Ca2+-free PSS for 50–100 seconds, followed by treatment with 100nM ANG II in the continued presence of TMB-8 and Ca2+-free PSS(100–300 seconds). Following exposure to ANG II, the cells were washed for an additional 100 seconds in the solution containing TMB-8 and Ca2+-free PSS (300–400 seconds). Additionally, experiments evaluating the effect of IP3 receptor blockade in the presence of chloride channel blockade were performed. Cells were exposed to a solution containing TMB-8 in the presence of 100μM DPC for 50 seconds, followed by treatment with 100nM ANG II in the continued presence of TMB-8 and DPC(100–300 seconds). Following exposure to ANG II, the cells were washed for an additional 100 seconds in the solution containing TMB-8 and DPC (300–400 seconds).

Data Analysis

Fluorescence intensity measurements were converted to nanomolar calcium concentrations based on calibration procedures previously described (13). Baseline [Ca2+]i was calculated by taking the average value of the five-second period before addition of ANG II to the chamber. Peak response was the maximum value of [Ca2+]i reached upon addition of ANG II minus the baseline, while sustained [Ca2+]i levels were calculated as the average of the last five seconds value during ANG II exposure. We also calculated the time at the initial peak and from the peak value to a 50% reduction in [Ca2+]i (50% time point) following the peak response in order to better characterize the shape of the post-peak response. Mean values ± SEM are presented for the peak, sustained and 50% time point values, and all statistical comparisons were performed using one-way analysis of variance. A p value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

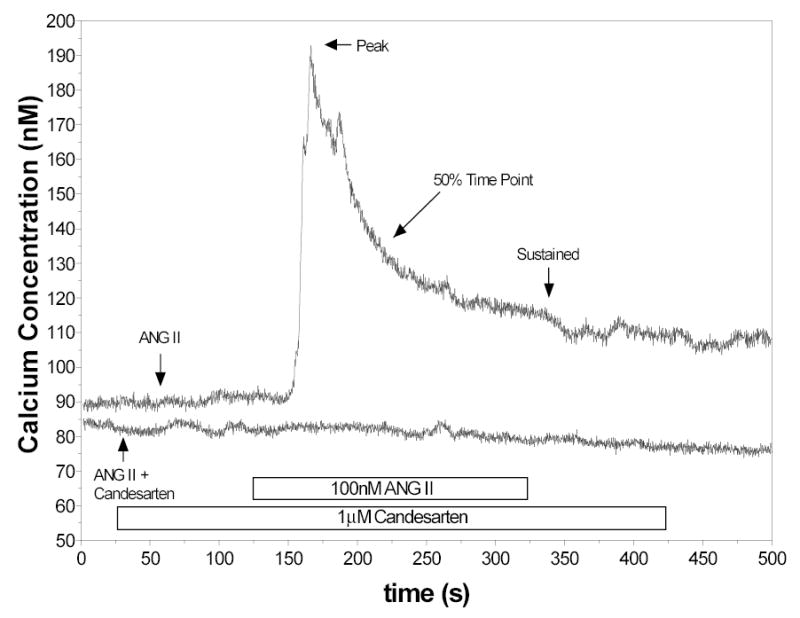

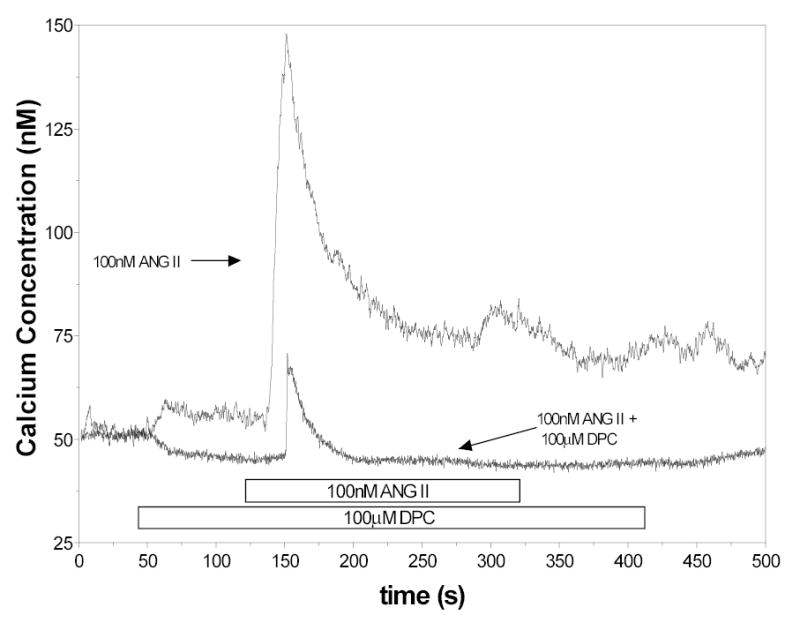

Figure 1 depicts a typical control response to 100nM ANG II in RVSMC. As previously reported (13), the response is characterized by a rapid increase in [Ca2+]i followed by a reduction to a plateau phase. For the population of cells we examined during all control conditions (n=35), mean resting [Ca2+]i was 75 ± 9 nM, the mean peak response was 74 ± 6 nM Ca2+ above baseline and the plateau, or sustained phase, was 12 ± 2 nM Ca2+ above baseline. For the population of control responses exposed only to ANG II, the 50% time point was 32 ± 4 seconds. For each series of experiments, the experimental responses were compared to their respective control responses. The mean time of the peak response was determined to be 33 ± 2 seconds after exposure to ANG II including the delay time of the system.

Figure 1.

Representative control response to 100nM ANG II showing immediate increase in [Ca2+]i followed by a gradual return to a sustained phase. Also shown is a representative tracing obtained in the presence of candesartan (1 μm).

None of the cells pretreated with candesartan (n=5) responded to ANG II (Figure 1). In the presence of candesartan, neither the peak response nor the sustained response could be determined.

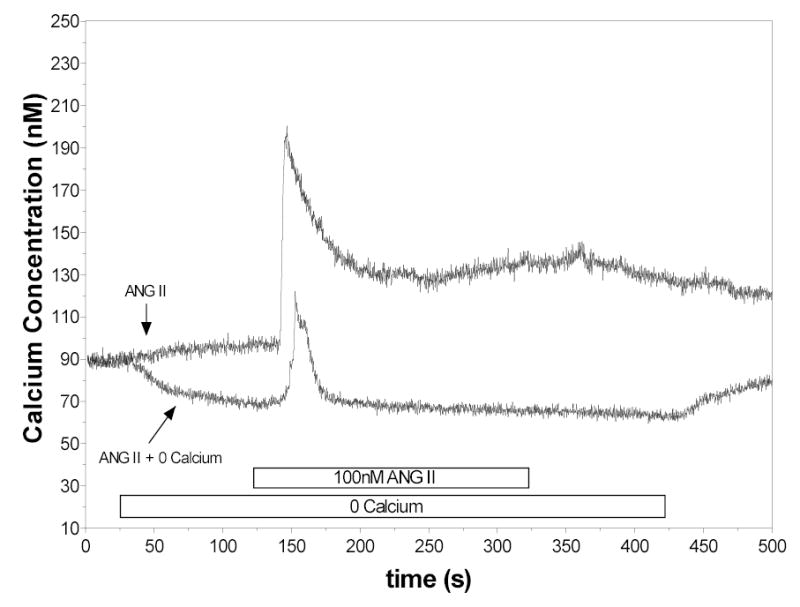

As shown in Figure 2, responses in a nominally Ca2+-free PSS (n=8) were markedly diminished. In reduced extracellular Ca2+, the mean peak response to ANG II was 42 ± 7 nM Ca2+, compared to 83 ± 13 nM Ca2+ for the peak response; however, the average sustained value was below baseline (–9.6 ± 2.5 nM Ca2+). In addition, the increase in [Ca2+]i was very short lived when extracellular Ca2+ was absent. The 50% time point occurred 11 ± 1 seconds after the peak, compared to 32 ± 7 seconds for corresponding control cells (p< 0.05 versus control). The time of the peak response (31 ± 3) was not different than that measured for control.

Figure 2.

Responses of RVSMC to ANG II in presence of Ca2+ containing solutions and in Ca2+ free solutions. In these series, the peak response was attenuated and the sustained response was not present.

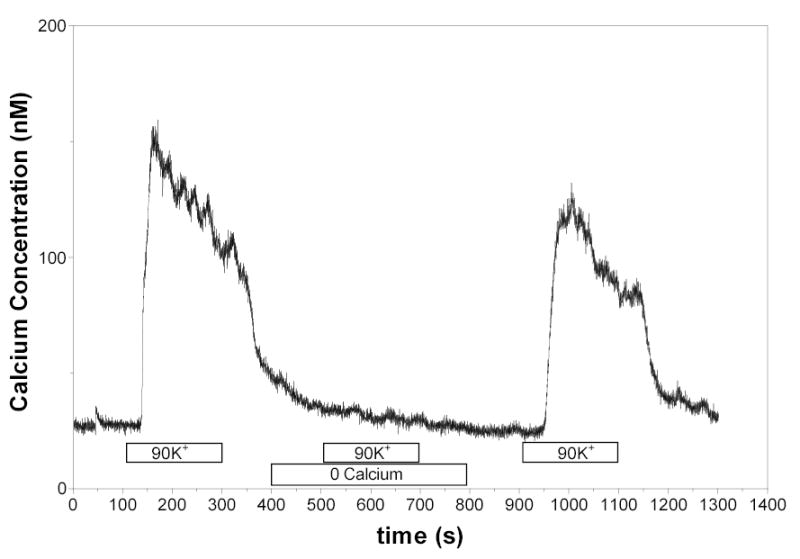

The Ca2+ responses to high KCl were used to evaluate the possibility that the ANG II mediated increases in [Ca2+]i in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ were due to influx from residual Ca2+ in the media. As shown in Figure 3, the responses to a depolarizing concentration of KCl included a strong peak response and a sustained plateau. However, [Ca2+]i failed to increase when the KCl solution was added to cells bathed in a Ca2+ free solution. As previously reported (13), 90 mM potassium failed to initiate either peak or sustained responses in RVSMC bathed in a nominally calcium free medium. When extracellular Ca2+ was restored to 1.8mM, the same RVSMC responded to KCl in a similar manner to the initial response. These data indicate that membrane depolarization and subsequent influx of Ca2+ from extracellular sources are not responsible for the increases in [Ca2+]i in response to ANG II observed in the presence of a nominally Ca2+ free solution.

Figure 3.

[Ca2+]i responses in cells exposed to 90 mM potassium in 1.8 mM Ca2+ solution and in a nominally calcium free solution. In the absence of extracellular Ca2+, the high KCl solution did not elicit any increases in [Ca2+]i .

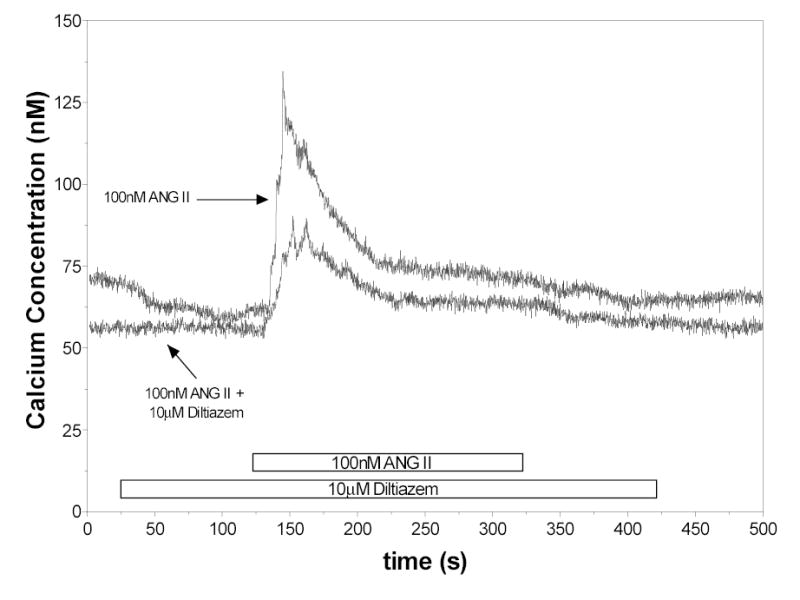

A representative experiment evaluating responses to ANG II in the presence of diltiazem (n=10) is shown in Figure 4. Blockade of L-type calcium channels produced a reduction in both the peak as well as the sustained responses. The mean peak response to ANG II in the presence of 10μM diltiazem was 24 ± 8 nM Ca2+ compared to the control value of 54 ± 3 nM Ca2+ in this series. However, the sustained [Ca2+]i in the presence of diltiazem was 4.2 ± 2.1 nM Ca2+ compared to 11 ± 2 nM Ca2+ for the control. The 50% time point was not statistically different for the two groups at 27 ± 2 seconds in the presence of diltiazem, compared to 21 ± 5 seconds in the control.

Figure 4.

Effects of 10μM diltiazem on the [Ca2+]i responses to ANG II.

The responses of RVSMC to ANG II in the presence of the chloride channel blocker, DIDS (n=11), were essentially abolished. The average peak and sustained responses were not different from zero (3.6 ± nM and 4.0 ± 1 nM respectively).

Because of the effects observed with DIDS, further studies were done evaluating the responses to ANG II in the presence of other chloride channel blockers. The responses to ANG II in the presence of 100μM DPC are shown in Figure 5. With 100μM DPC (n=17), the peak response was markedly reduced and the sustained response was abolished. The mean peak value for [Ca2+]i was 18 ± 5 nM while mean sustained [Ca2+i] was 0.08 ± 1 nM. The 50% time point in [Ca2+] was 15 ± 2 seconds. In the presence of 500μM DPC the peak response to ANG II was reduced even further (n=7). The mean peak value for [Ca2+]i was 7 ± 2 nM while mean sustained [Ca2+i] was −0.3 ± 1 nM, compared with 71 ± 6 nM and 5 ± 3 nM for the corresponding control.

Figure 5.

[Ca2+]i responses to ANG II in control cells and cells treated with 100μM DPC

The possible contribution of chloride channels was assessed further in cells in which intracellular Cl− was depleted by incubation in an isotonic solution containing only 3 mM Cl−. The cells were then exposed to ANG II in the presence of normal chloride concentrations (140 mM). Mean initial peak values were 38 ± 4 nM compared to 71 ± 5 nM for the corresponding control and mean sustained phase values were 3 ± 1 nM. The 50% time point Ca2+ was not different from that observed under control conditions.

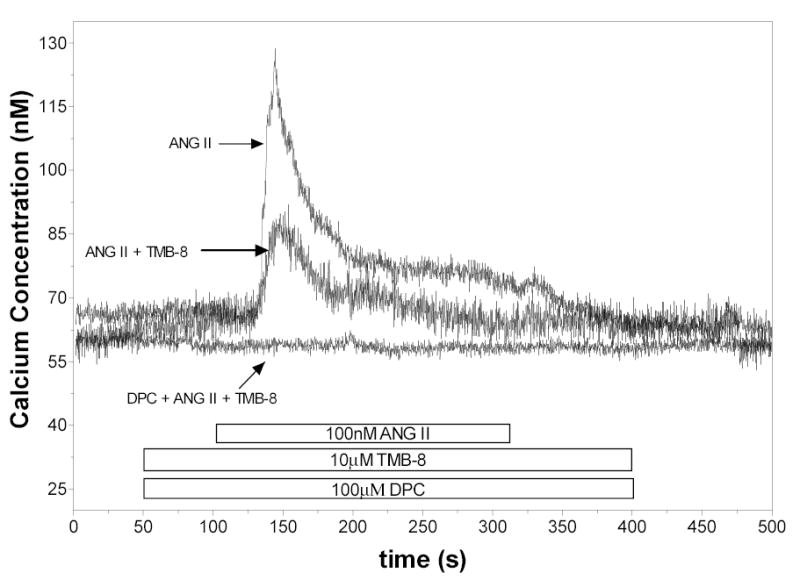

In the presence of IP3 receptor blockade with 10μM TMB-8 (n=6), the peak was reduced to 22 + 8 nM compared to 94 ± 6 nM for the control. The 50% time point was not different from that observed under control conditions. Exposure to 10μTMB-8 in the presence of Ca2+-free medium (n=9) abolished the ANG II response (Recorded peak and sustained values were 4 ± 1 nM and −21 ± 6 nM respectively). When exposed to 100μM DPC and 10μM TMB-8 (n=7), the ANG II response was also prevented (Recorded peak and sustained values were 5 ± 1 nM and −2 ± 2 nM respectively). These data are shown in figure 6.

Figure 6.

[Ca2+]i responses to ANG II in control cells, cells treated with 10μM TMB-8 and cells treated with 100μM DPC + 10μM TMB-8.

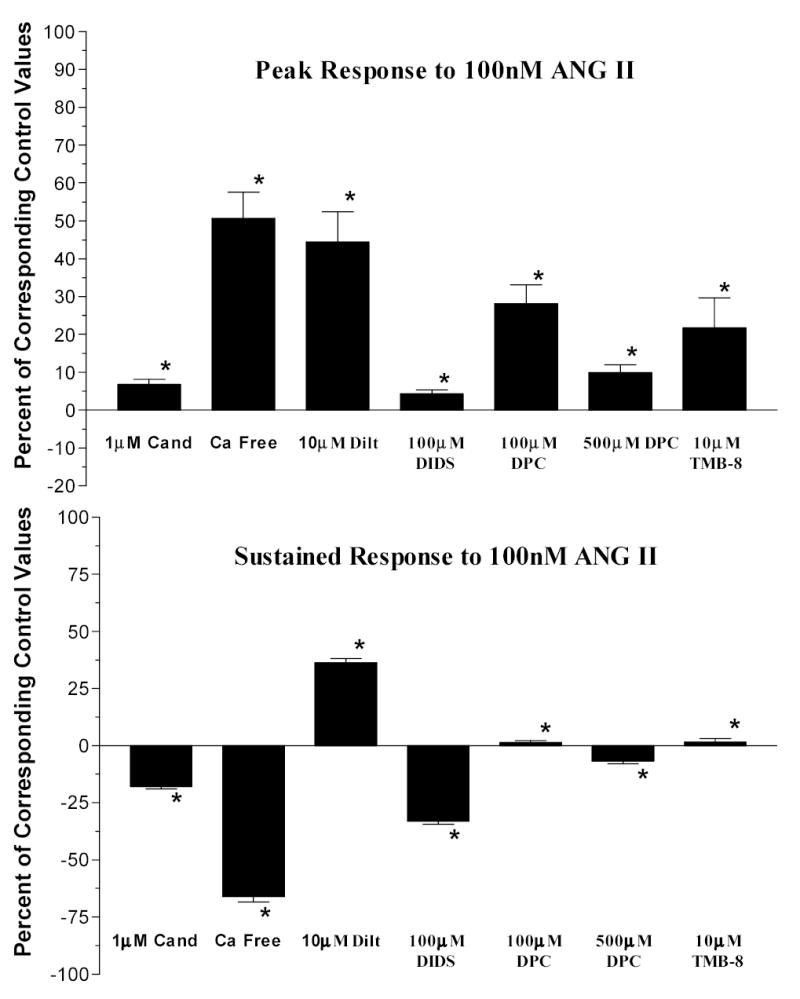

Figure 7 compares the corresponding peak and sustained responses of each of the groups compared to their individual controls expressed as a percentage of control peak responses to ANG II. As shown, peak responses were absent in the cells exposed to candesartan and DIDS. Removal of extracellular Ca2+ and exposure to diltiazem, DPC, and TMB-8 reduced but did not abolish the peak response. Sustained responses were not observed in cells incubated in calcium free solution or treated with chloride channel blockers. L-type calcium channel blockade yielded a reduction in the magnitude of the sustained response but it was not completely abolished (p<0.05 versus control).

Figure 7.

Mean peak responses and sustained responses to 100nM ANG II expressed as percentage of the mean peak of the corresponding control responses. (*=p<0.05)

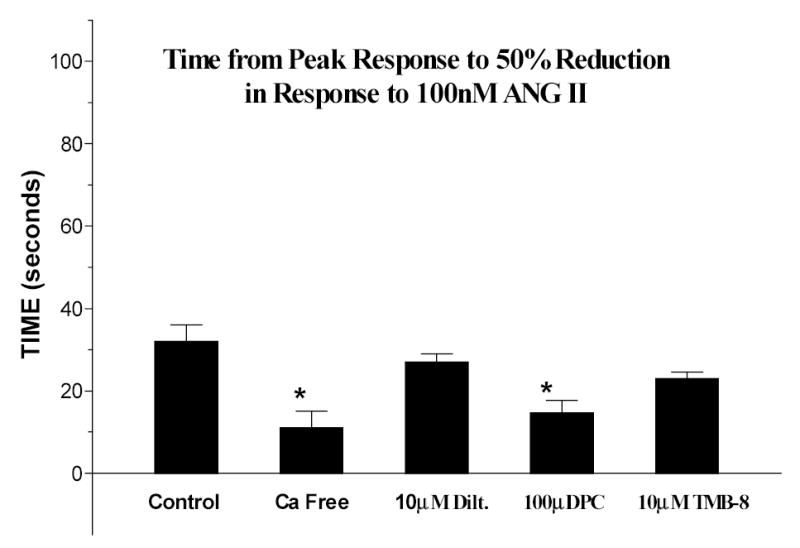

Figure 8 summarizes the 50% time points. Control values represent the mean of all control cells for all series of experiments. Cells exposed to ANG II in the presence of the calcium free medium and DPC incubation showed a significantly reduced time for a 50% return to baseline (p<0.05 versus control). Additionally, blockade of mobilization alone did not reduce the 50% time point indicating continued influx from extracellular sources. In contrast, prevention of extracellular entry did reduce the 50% time point.

Figure 8.

Mean time between the peak response and a 50% reduction in [Ca2+]i. (*=p<0.05)

Discussion

Although much is known about ANG II mediated signaling processes in vascular smooth muscle cells, the temporal cascade leading to activation of calcium entry pathways remains uncertain(32). The present results provide information regarding the sequence of events responsible for ANG II mediated increases in [Ca2+]i in RVSMC. While the role of extracellular calcium is crucial in the response of RVSMC, the mechanisms contributing to the initial increases in intracellular calcium are still not clear. The majority of in vitro and in vivo data support a role for both influx and mobilization in the afferent arteriolar Ca2+ response or the renal microvascular constrictor response to ANG II. These studies include direct assessments of afferent arteriolar calcium responses (4; 6) and of cultured preglomerular smooth muscle cells, (28) which established that ANG II-mediated elevations in calcium involve influx and mobilization mechanisms. Functional evidence for a role of calcium influx comes from numerous studies employing calcium channel blockade to inhibit ANG II mediated vasoconstriction of afferent arterioles. Functional evidence in support of a role for calcium mobilization in the afferent arteriolar response to ANG II comes from the work of Imig et al, (11) where calcium store depletion attenuated ANG II-mediated vasoconstriction. Whole animal in vivo evidence is provided by the work of Ruan and Arendshorst (29) where TMB-8 was shown to attenuate ANG II mediated renal vasoconstriction. Thus consistent with the current report, there is substantial evidence supporting the contribution of both mobilization and influx mechanisms in ANG II mediated vasoconstriction of afferent arterioles.

It has generally been considered that the rapid increase in [Ca2+]i is due primarily to mobilization of calcium from intracellular stores; however, our results indicate that the magnitude of even this early response is highly dependant on calcium entry from the extracellular environment. Another finding was that the chloride channel blockers either prevented or markedly attenuated the early peak response as well as the sustained response, indicating that chloride channel activation is of critical importance and may also be an early event.

A previous study using equimolar concentrations of ANG II and candesartan showed an 88% inhibition of intracellular calcium increase in response to ANG II (17). We showed in our population of cells, that the AT1 receptor blocker, candesartan, completely prevents any change in [Ca2+]i in response to ANG II. In the review of ANG II receptor antagonists by Hernández et al (10), candesartan was shown to have a high affinity for the AT1 receptor subtype without exerting agonistic effects. At very high doses they have been shown to also bind AT2 receptors. The 1μM dosage used is low enough to conclude that AT1 receptors are being selectively antagonized. A possible explanation of the difference in our findings was the use of a higher concentration of candesartan (10−6 M) and the pretreatment of cells with the blocker. Our findings indicate that AT1 receptors are completely responsible for the calcium response to ANG II.

When RVSMC were tested in a calcium-free medium, there was clearly a peak response to ANG II but it was substantially reduced compared to the control peak response. Previous studies have suggested that the calcium response may be abolished by the removal of calcium from the media (3; 16; 17; 23). Our data demonstrate that in the absence of extracellular calcium, there continues to be an increase in intracellular calcium albeit smaller in magnitude. Thus, there is an evident peak response, (50% of the control value) that is likely the result of mobilization of calcium from intracellular stores. In experiments testing the response to potassium induced depolarization, (90mM) the results indicate that in the presence of the calcium-free medium, influx of residual calcium was insufficient to cause a detectable increase in [Ca2+]i in response to KCl induced depolarization and thus was not responsible for the increased [Ca2+]i response to ANG II observed in the normally Ca2+ free medium. Nevertheless, the markedly smaller response observed in the calcium free media support an important role for Ca2+ influx even in the early transient response. Our results also support the conclusion that calcium influx contributes to the sustained increases in [Ca2+]i in that no sustained phase was observed in the presence of calcium-free medium (1; 23; 26; 32). In addition the 50% time point in the presence of calcium-free medium was also markedly reduced, further emphasizing that calcium entry from the extracellular compartment is an integral part of the initial peak response as well as the major source of the sustained response.

Experiments utilizing diltiazem demonstrated that blockade of L-type calcium channels in rat RVSMC reduces the peak response to ANG II as well as the sustained response. Diltiazem is a calcium channel blocker specific for voltage-gated L-type calcium channels (7). Diltiazem and other drugs like it have been shown to have nonspecific effects on other parts of the action potential (21) but we saw no evidence of such at the dosage we used in our preparation. The peak response was suppressed similarly in calcium free conditions and in the presence of diltiazem. This suggests that the influx component associated with the peak response occurs largely through activation of L-type calcium channels. In contrast, blockade by diltiazem only reduced the sustained response whereas removal of extracellular calcium abolished the sustained response completely. These data indicate that calcium influx during the sustained phase still occurs even in the presence of L-type calcium channel blockers. While this may be due to partial blockade of the calcium channels; it seems more likely that the remaining calcium influx is due to continued activity of other calcium entry pathways, such as T-type Ca2+ channels or store operated Ca2+ channels (8; 32; 35).

The experiments in which RVSMC were exposed to DIDS and DPC indicate that blockade of the chloride channels leads to prevention or marked attenuation of the initial peak as well as the sustained response. Because blockade by DIDS and DPC reduced the peak response to ANG II to a greater extent than removal of extracellular calcium, the data suggest that the triggering of calcium release from the intracellular calcium stores as well as the initial Ca2+ entry from extracellular sources are also blocked or, at least, attenuated. DIDS is a non-selective chloride channel blocker while DPC is a more specific chloride channel blocker (20). At the 100μM dosage we used, DPC is more selective for calcium activated chloride channels than for other chloride channels (2). While specific chloride channel blockers have not yet been developed, the sum of the findings with DIDS and DPC increase our confidence that chloride channels are being blocked. Additionally, we have run a series of experiments using potassium-induced depolarization in the presence of DPC to investigate possible nonspecific actions it may have on voltage-gated calcium channels. We found no evidence of calcium channel blockade by DPC. Thus, the results suggest that activation of chloride channels occurs at a much earlier time than would be expected if it were the consequence of Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. Activation of chloride channels may be an early event and could possibly be directly linked to the AT1 receptor; accordingly, chloride channel activation may contribute to the early peak response rather than being a consequence. Thus, mobilization of intracellular stores and the depolarization induced increases in Ca2+ entry from the extracellular environment are not necessarily sequential but rather are coincident events with both contributing to the peak response. If this is the case, however, the question regarding the mechanism responsible for the depolarization induced activation of L-type Ca2+ channels becomes apparent. One explanation to reconcile these data is to consider that AT1 receptor activation somehow directly triggers the activation of the chloride channel rather than being the result of increases in cytosolic Ca2+ due to release from intracellular stores.

Analyzing the chain of events temporally, we see that both reducing the extracellular calcium concentration and blocking the chloride channels with DPC leads to similar decreases in the 50% time point. This indicates that, in addition to modification of the peak and sustained value, removing calcium and blocking chloride channels changes the physical characteristics of the ANG II response pattern. When RVSMC were incubated in a 3mM chloride solution and exposed to ANG II along with a higher concentration of chloride the response was similar to that observed in cells exposed to lower levels of extracellular calcium, additionally the 50% time point was similar to that seen in calcium free media. These data strongly suggest a temporal link between [Ca2+]i mobilization and chloride channels, specifically that both need to be functional in order to produce the robust peak and sustained responses observed under control conditions.

TMB-8 is a putative IP3 receptor blocker and has been used often (28). It has been shown to selectively block IP3 mediated calcium release from intracellular stores. TMB-8 reduced the peak and abolished the sustained response. In the presence of Ca2+ free media and TMB-8 the response was abolished, indicating a complete blockade of IP3. This indicates that the response observed under TMB-8 treatment and normal Ca2+ is due to entry from extracellular sources; moreover it suggests that extracellular entry is occurring independently of intracellular mobilization. Furthermore, this independent extracellular entry appears to be mediated by chloride channels, because no response was observed when DPC was combined with TMB-8.

In summary, our study confirms the important role of AT1 receptors in response to ANG II and the subsequent increase in intracellular calcium that occurs. We have demonstrated that in addition to mobilization of calcium from internal stores, calcium influx through voltage gated calcium channels contributes to the early elevation of intracellular calcium in preglomerular RVSMC. The study suggests that subsequent influx of calcium is responsible for maintaining the elevated [Ca2+]i; this influx is at least partially dependant on the functioning of chloride channels as well as L-type calcium channels. Chloride channel blockers attenuate both the early peak, as well as the sustained responses, suggesting that chloride channel activation contributes to the initial rapid response. Additionally, intracellular Cl− depletion attenuates the peak and sustained responses as well, lending further credence to the hypothesis that chloride channels contribute to the initial peak response concurrently with the mobilization of intracellular calcium stores. Finally the results indicated that when [Ca2+]i store mobilization is blocked by TMB-8 a response is still observed and when chloride channels are blocked that response is prevented, suggesting that ANG II responses in RVSMC occur as a result of concurrent extracellular Ca2+ entry and intracellular Ca2+ mobilization.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from NHLBI (HL 18426), from NIDDK (DK44628), by the Health Excellence Fund from the Louisiana Board of Regents and by NIH grant P20RR017659 from the Institutional Developmental Award (IdeA) program of NCRR. We acknowledge Debbie Olavarrieta for assistance in preparation of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Arendshorst WJ, Brannstrom K, Ruan X. Actions of angiotensin II on the renal microvasculature. [Review] [100 refs] J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10 (Suppl 11):S149–S161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baron A, Pacaud P, Loirand G, Mironneau C, Mironneau J. Pharmacological block of Ca(2+)-activated Cl- current in rat vascular smooth muscle cells in short-term primary culture. Pflugers Arch. 1991;419:553–558. doi: 10.1007/BF00370294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carmines PK. Segment-specific effect of chloride channel blockade on rat renal arteriolar contractile responses to angiotensin II. Am J Hypertens. 1995;8:90–94. doi: 10.1016/0895-7061(94)00170-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carmines PK, Fowler BC, Bell PD. Segmentally distinct effects of depolarization on intracellular [Ca2+] in renal arterioles. Am J Physiol-Renal Physiol. 1993;265:F677–F685. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.265.5.F677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carmines PK, Navar LG. Disparate effects of Ca channel blockade on afferent and efferent arteriolar responses to ANG II. Am J Physiol-Renal Physiol. 1989;256:F1015–F1020. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.256.6.F1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conger JD, Falk SA, Robinette JB. Angiotensin II-induced changes in smooth muscle calcium in rat renal arterioles. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1993;3:1792–1803. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V3111792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feng MG, Li M, Navar LG. T-type calcium channels in the regulation of afferent and efferent arterioles in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286:F331–F337. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00251.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng MG, Navar LG. Angiotensin II-mediated constriction of afferent and efferent arterioles involves T-type Ca2+ channel activation. Am J Nephrol. 2004;24:641–648. doi: 10.1159/000082946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernandez-Hernandez R, Sosa-Canache B, Velasco M, Armas-Hernandez MJ, Armas-Padilla MC, Cammarata R. Angiotensin II receptor antagonists role in arterial hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2002;16 (Suppl 1):S93–S99. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imig JD, Cook AK, Inscho EW. Postglomerular vasoconstriction to angiotensin II and norepinephrine depends on intracellular calcium release. Gen Pharmac. 2000;34:409–415. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(01)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inscho EW, LeBlanc EA, Pham BT, White SM, Imig JD. Purinoceptor-mediated calcium signaling in preglomerular smooth muscle cells. Hypertension. 1999;33(part II):195–200. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.1.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inscho EW, Mason MJ, Schroeder AC, Deichmann PC, Stiegler ID, Imig JD. Agonist-induced calcium regulation in freshly isolated renal microvascular smooth muscle cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:569–579. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V84569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inscho EW, Schroeder AC, Deichmann PC, Imig JD. ATP-mediated Ca2+ signaling in preglomerular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:F450–F456. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.276.3.F450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iversen BM, Arendshorst WJ. ANG II and vasopressin stimulate calcium entry in dispersed smooth muscle cells of preglomerular arteiroles. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:F498–F508. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.274.3.F498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iversen BM, Arendshorst WJ. ANG II and vasopressin stimulate calcium entry in dispersed smooth muscle cells of preglomerular arterioles. Am J Physiol-Renal Physiol. 1998;274:F498–F508. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.274.3.F498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iversen BM, Arendshorst WJ. AT1 calcium signaling in renal vascular smooth muscle cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:S84–S89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen BL, Ellekvist P, Skott O. Chloride is essential for contraction of afferent arterioles after agonists and potassium. Am J Physiol-Renal Physiol. 1997;272:F389–F396. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.272.3.F389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen BL, Skott O. Blockade of chloride channels by DIDS stimulates renin release and inhibits contraction of afferent arterioles. Am J Physiol-Renal Physiol. 1996;270:F718–F727. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.270.5.F718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jentsch TJ, Stein V, Weinreich F, Zdebik AA. Molecular structure and physiological function of chloride channels. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:503–568. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karlsberg RP, Aronow WS. Calcium channel blockers: indications and limitations 1. Clinical pharmacology and use as antiarrhythmic agents. Postgrad Med. 1982;72:97–4. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1982.11716250. 107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Large WA, Wang Q. Characteristics and physiological role of the Ca(2+)-activated Cl- conductance in smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:C435–C454. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.2.C435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loutzenhiser K, Loutzenhiser R. Angiotensin II-induced Ca(2+) influx in renal afferent and efferent arterioles: differing roles of voltage-gated and store-operated Ca(2+) entry. Circ Res. 2000;87:551–557. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.7.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Navar LG. Integrating multiple paracrine regulators of renal microvascular dynamics. Am J Physiol-Renal Physiol. 1998;274:F433–F444. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.274.3.F433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Navar LG, Inscho EW, Imig JD, Mitchell KD. Heterogeneous activation mechanisms in the renal microvasculature. [Review] [30 refs] Kidney International -Supplement. 1998;67:S17–S21. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.06704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Navar LG, Inscho EW, Majid SA, Imig JD, Harrison-Bernard LM, Mitchell KD. Paracrine regulation of the renal microcirculation. [Review] [1214 refs] Physiol Rev. 1996;76:425–536. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.2.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Purdy KE, Arendshorst WJ. Prostaglandins buffer ANG II-mediated increases in cytosolic calcium in preglomerular VSMC. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:F850–F858. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.277.6.F850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Purdy KE, Arendshorst WJ. Iloprost inhibits inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate-mediated calcium mobilization stimulated by angiotensin II in cultured preglomerular vascular smooth muscle cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:19–28. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V12119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruan X, Arendshorst WJ. Calcium entry and mobilization signaling pathways in ANG II-induced vasoconstriction in vivo. Am J Physiol-Renal Physiol. 1996;270:F398–F405. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.270.3.F398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salomonsson M, Arendshorst WJ. Calcium recruitment in renal vasculature: NE effects on blood flow and cytosolic calcium concentration. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:F700–F710. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.276.5.F700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salomonsson M, Arendshorst WJ. Norepinephrine-induced calcium signaling pathways in afferent arterioles of genetically hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;281:F264–F272. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.281.2.F264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salomonsson M, Sorensen CM, Arendshorst WJ, Steendahl J, Holstein-Rathlou NH. Calcium handling in afferent arterioles. Acta Physiol Scand. 2004;181:421–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201X.2004.01314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steendahl J, Holstein-Rathlou NH, Sorensen CM, Salomonsson M. Effects of chloride channel blockers on rat renal vascular responses to angiotensin II and norepinephrine. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286:F323–F330. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00017.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takenaka T, Kanno Y, Kitamura Y, Hayashi K, Suzuki H, Saruta T. Role of chloride channels in afferent arteriolar constriction. Kidney Int. 1996;50:864–872. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takenaka T, Suzuki H, Okada H, Inoue T, Kanno Y, Ozawa Y, Hayashi K, Saruta T. Transient receptor potential channels in rat renal microcirculation: Actions of angiotensin II. Kidney Int. 2002;62:558–565. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]