Abstract

Interleukin (IL)-1β induces the expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) implicated in cartilage resorption and joint degradation in osteoarthritis (OA). Pomegranate fruit extract (PFE) was recently shown to exert anti-inflammatory effects in different disease models. However, no studies have been undertaken to investigate whether PFE constituents protect articular cartilage. In the present studies, OA chondrocytes or cartilage explants were pretreated with PFE and then stimulated with IL-1β at different time points in vitro. The amounts of proteoglycan released were measured by a colorimetric assay. The expression of MMPs, phosphorylation of the inhibitor of κBα (IκBα) and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) was determined by Western immunoblotting. Expression of mRNA was quantified by real-time PCR. MAPK enzyme activity was assayed by in vitro kinase assay. Activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) was determined by electrophoretic mobility shift assay. PFE inhibited the IL-1β–induced proteoglycan breakdown in cartilage explants in vitro. At the cellular level, PFE (6.25–25 mg/L) inhibited the IL-1β–induced expression of MMP-1, -3, and -13 protein in the medium (P < 0.05) and this correlated with the inhibition of mRNA expression. IL-1β–induced phosphorylation of p38-MAPK, but not that of c-Jun-N-terminal kinase or extracellular regulated kinase, was most susceptible to inhibition by low doses of PFE, and the addition of PFE blocked the activity of p38-MAPK in a kinase activity assay. PFE also inhibited the IL-1β–induced phosphorylation of IκBα and the DNA binding activity of the transcription factor NF-κB in OA chondrocytes. Taken together, these novel results indicate that PFE or compounds derived from it may inhibit cartilage degradation in OA and may also be a useful nutritive supplement for maintaining joint integrity and function.

Keywords: osteoarthritis, pomegranate, signal transduction, cartilage

Osteoarthritis (OA)3 is the most common form of joint disorder associated with aging in which subchondral bone changes and progressive erosion of articular cartilage results in the loss of joint function (1,2). At the molecular level, OA is characterized by an imbalance between anabolic and catabolic pathways in which articular cartilage is the principal site of the tissue injury response. High prevalence, associated pain, disability, and a large socioeconomic burden for the long-term treatment and care of patients make OA an important health and economic challenge (3). Although the etiology of OA is not completely understood, it is believed that sustained production of the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL)-1β in the affected joints may play a pivotal role in OA pathogenesis. IL-1β–induced upregulation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), especially MMP-1 and -13, is a key event in the irreversible breakdown of cartilage matrix via digestion of type-II collagen and the consequent release of matrix proteoglycan (glycosaminoglycan; GAG) from the cartilage (4,5). The recognition that inflammatory and destructive components of OA are distinct disease processes and that cartilage degradation may continue even when inflammation is suppressed (6) points to the limited effectiveness of current treatment regimens that are also hampered by poor tolerability and inability to slow joint destruction and disease progression. This has generated considerable interest in the identification and development of new approaches and reagents to treat and inhibit, if not abolish the progress of the disease (7). Plant-derived flavonoids, present in fruits, leaves, and vegetables have attracted much attention recently due to their beneficial health effects in several disease models (8–10). Thus, the present study was undertaken to test the efficacy of a flavonoid-rich extract of pomegranate fruit (PFE) against IL-1β–induced release of GAG by human cartilage explants, the production of MMP-1, -3, and -13 by human chondrocytes, and IL-1β–induced mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activation using a well-defined in vitro system.

Pomegranate (Punica granatum L, Punicaceae) is an edible fruit native to Persia that is grown and consumed around the world, including the United States; it has been revered through the ages for its medicinal properties (11). The edible part of pomegranate is rich in anthocyanins, a group of polyphenolic compounds that possess antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities (12,13). Studies in animal models of cancer suggest that PFE consumption may be anticarcinogenic (14–16), whereas studies in mice and humans indicate that it may also have a potential therapeutic and chemopreventive adjuvant effect in cardiovascular disorders (17). Anthocyanins were shown to be effective inhibitors of lipid peroxidation, the production of nitric oxide (NO) and inducible nitric oxide synthase activity in different model systems (17,18). In a comparative analysis, anthocyanins from pomegranate fruit were shown to possess higher antioxidant activity than vitamin E (α-tocopherol), ascorbic acid, and β-carotene (19). After consumption, anthocyanins are efficiently absorbed as glycosides from the stomach and rapidly excreted into bile as intact and metabolized forms (20). Antioxidant activities of the 3 major anthocyanidins present in pomegranate (delphinidin, cyanidin, and pelargonidin) were also evaluated and shown to be potent antioxidants (21). In related studies, prodelphinidins inhibited cyclooxygenase-2 and lipoxygenase activity and production of prostaglandins E2; they activated the synthesis of type-II collagen in human chondrocytes (22,23). Afaq et al. (15) recently analyzed the constituents of PFE and showed that it is a rich source of anthocyanins such as delphinidin. Their results also showed that pretreatment of mouse skin with PFE modulated the activation of MAPKs and NF-κB in the 12-o-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate (TPA)-induced or UVB-induced skin carcinogenesis model (15). Other studies showed that the antiproliferative effect of delphinidin is triggered by extracellular regulated kinase (ERK)-1/2 activation, independent of the nitric oxide pathway and correlates with the suppression of cell progression by blocking the cell cycle in G(0)/G(1) phase (24). In the TPA-induced cell transformation model, delphinidin, but not peonidin, blocked the phosphorylation of protein kinases in the ERK pathway at early times and the c-Jun-N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling pathway at later times, whereas p38-MAPK was not inhibited by delphinidin (25). These and other results suggest that the effects of anthocyanins may be cell and tissue-type specific but little information is available on the effects of PFE on cartilage integrity and joint function. Using a well-characterized in vitro model we demonstrated that PFE constituents inhibit human cartilage matrix breakdown. These and other novel findings reported here extend the previous findings substantially and suggest that consumption of PFE may be beneficial in maintaining cartilage integrity, potentially helping patients with degenerative joint diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Tissue culture medium and related reagents were purchased from either Mediatech or InVitrogen. Recombinant human IL-1β was purchased from R & D Systems. 1,9-Dimethylmethylene blue (DMMB) and other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Polyclonal goat anti-human MMP-1, MMP-3, and MMP-13 antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated state-specific antibodies for p-38 MAPK, JNK p54/p46, and ERK p44/p42, recombinant activated transcription factor-2 (ATF-2), and c-Jun proteins were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology and Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Pierce Biotechnology.

Preparation of anthocyanin-rich pomegranate fruit extract.

Powdered pomegranate fruit was purchased in bulk from a commercial vendor (FutureCeuticals) and the anthocyanin-rich fraction was isolated as previously described (26). The methanol-soluble fraction (PFE) was freeze-dried (Labconco), divided into aliquots, and stored at −20°C. Fresh PFE solution was prepared by dissolving the required concentration in sterile PBS, filter sterilizing, and adding it to the culture medium.

Human chondrocyte culture.

Human OA cartilage samples were procured through the Cooperative Human Tissue Network and the Tissue Procurement Facility of the University Hospitals of Cleveland and Case Western Reserve University. The protocol to use discarded human tissue was approved by the Institutional Review Board of University Hospitals of Cleveland. Chondrocytes were prepared by the enzymatic digestion of femoral head cartilage as previously described (27). Chondrocytes were incubated in serum-free medium overnight and then treated with IL-1β (5 μg/L) and IL-1β + PFE (6.25–50 mg/L) for time periods indicated under each figure. Chondrocytes cultured without IL-1β or PFE served as controls.

Cell viability assay.

The effect of PFE on the viability of chondrocytes was studied using the MTT (3-[4,5-dimethyl thiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide)-based Cell Proliferation and Viability Assay system according to the instructions of the manufacturer (R&D Systems), as previously described (28). The percentage of viable cells/well was calculated by the formula: [(Absorbance of untreated/Absorbance of treated) × 100]. The results were expressed as “Viable cells (%)” assuming that 100% of cells were viable at the time of plating.

Quantitation of GAG.

Full-thickness cartilage slices (40–50 mg) were dissected and washed with sterile PBS. Two cartilage pieces (approximately equal in size and weight) were transferred to each well of a 24-well, flat-bottomed plate (NUNC A/S) containing DMEM supplemented with antibiotics and 10% fetal calf serum and cultured for 24 h; they were cultured without serum overnight and then treated for 72 h in fresh medium without serum as follows: IL-1β (10 μg/L), IL-1β + PFE (25 mg/L), IL-1β + PFE (50 mg/L), and PFE alone at 25 and 50 mg/L. Explants cultured in the absence of IL-1β and PFE were used as controls. At the end of incubation culture, the medium was collected from each group and a 50-μL aliquot was used to estimate the total GAG released into the medium by a colorimetric method employing DMMB (29). Values were calculated from a standard curve and expressed as μg GAG released/mg cartilage and compared with the levels detected in controls. The percentage of inhibition/induction was calculated relative to controls with the control values taken as 100%.

Western immunoblotting and analysis.

Chondrocyte cultures (80% confluent) were washed with HBSS, cultured without serum overnight, and then treated either with IL-1β alone or with different concentrations of PFE (6.25–50 mg/L) + IL-1β in serum-free medium for 24 h. Culture medium was collected and a 500-μL aliquot was concentrated using Microcon concentrators (Millipore) for 30 min at 25°C. Protein concentration was estimated using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay, and samples were resolved by SDS/PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad); the blot was probed with polyclonal goat anti-human MMP-1, -3, and -13 antibodies. To ensure equal loading of the proteins, we stained a similarly prepared Tris-Glycine gel with Coomassie blue stain (Gel-Code Blue, Pierce). To study the effect of PFE on IL-β–induced activation of MAPK, serum-starved chondrocytes were pretreated with PFE (6.25–50 mg/L) for 2 h followed by stimulation with IL-1β for 30 min. The Western blots were probed using rabbit polyclonal antibodies specific for phosphorylated and total human p38-MAPK, ERK p44/p42, JNK p54/p46, ATF-2 and c-Jun proteins and immunoreactive proteins were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence. Images were captured using the autoexposure feature of the AlphaInnotech Imaging System, and the data were analyzed statistically (see below).

In vitro kinase activity assay.

Activated JNK and p38-MAPK were immunoprecipitated from the lysates using antibodies specific for the phosphorylated forms of the kinases, and the kinase activity was determined in the presence and absence of PFE (25 mg/L) using glutathione S-transferase-c-Jun and ATF-2 fusion protein as substrates, respectively, essentially as described earlier (30).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

Human OA chondrocytes were stimulated with IL-1β or IL-1β + PFE (25 mg/L), and the nuclear proteins were prepared as previously described (5). Nuclear protein (2.5 μg) from each sample was used to detect the DNA binding activity of NF-κB using a commercially available EMSA kit with a biotin-labeled NF-κB consensus probe essentially according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Panomics).

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR.

Total cytoplasmic RNA was prepared from human chondrocytes using a commercially available kit according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Quiagen). Real-time quantitative RT-PCR with internal fluorescent hybridization probes was performed essentially as previously described (5). MMP-specific primer sets and their fluorescent probes used were described earlier (5,30). Fourfold serial dilutions of sample cDNA were used to generate curves of log input vs. threshold cycle. Expression of MMP-1, -3, and -13 mRNA was normalized to the levels of β-actin mRNA expression, and the results were expressed as fold induction relative to control.

Statistical analysis.

Each experiment was repeated to ensure reproducibility of the data using cartilage samples from sex-matched donors (mean age 62 ± 3 y, Caucasian women). Data obtained were analyzed using SAS/STAT Version 8.2 software package (SAS Institute). Statistical analyses included 1-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test. The ANOVA was performed using the General Linear Model using PROC GLM in SAS. Values presented are means ± SD. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

PFE blocked the effect of IL-1β on the viability of OA chondrocytes in vitro.

Treatment with IL-1β reduced the OA chondrocyte viability [see also (27)]. The addition of PFE to the culture medium did not negatively affect the viability of OA chondrocytes. Importantly, pretreatment of OA chondrocytes with PFE blocked the IL-1β–induced cytotoxic effects in vitro (results not shown).

PFE inhibited IL-1β–induced OA cartilage degradation in vitro.

Stimulation of OA cartilage explants with IL-1β (10 μg/L) resulted in the release of matrix proteoglycans into the culture medium in quantities greater than those in control cultures (P < 0.001, r = 0.973, Table 1). However, release of proteoglycans from the cartilage matrix into samples pretreated with PFE was inhibited compared with the samples treated with IL-1β alone (P < 0.001). Matrix proteoglycan release from samples pretreated with PFE was not greater than basal levels (Table-1). This suggests that the basal levels of proteoglycans released into the control samples could be due to the origin of the samples (surgery, disease) and/or cutting and shaving of cartilage pieces in the laboratory and hence was not amenable to inhibition.

TABLE 1.

Inhibition of IL-1β-induced proteoglycan release from OA cartilage explants by PFE in vitro

| GAG Released | % of Control | |

|---|---|---|

| μg/mg cartilage | ||

| Group | ||

| Control | 9.1 ± 1.15bc | 100 |

| IL-1β | 28.08 ± 2.51a | 308 |

| IL-1β + P25 | 12.13 ± 1.27b | 133 |

| IL-1β + P50 | 6.76 ± 0.40c | −26 |

| P25 | 7.13 ± 1.62c | −22 |

| P50 | 6.33 ± 0.57c | −31 |

Values are means ± SD, n = •••. Means in a column without a common letter differ, P < 0.001.

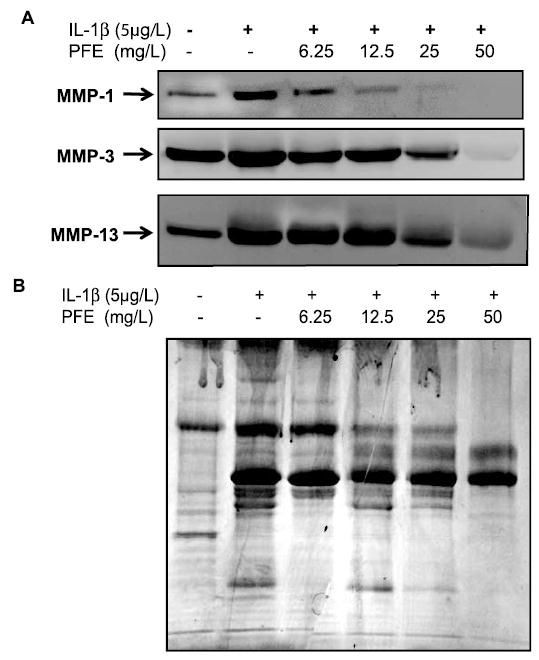

PFE inhibited the IL-1β-induced production of MMPs in OA chondrocytes.

IL-1β is a potent inducer of MMPs in cultured chondrocytes and articular cartilage in vitro (30–32). Although detectable levels of MMP-1, -3, and -13 were present in the control culture supernatants, expression of MMP-1, -3, and -13 was increased several-fold in cultures stimulated with IL-1β, but the effect was not uniform (Fig. 1A). Expression of MMP-13 in Il–1β stimulated OA chondrocytes was several-fold higher compared with controls, as judged by the intensity of antibody-reactive protein bands on the Western blot (P < 0.001). Pretreatment with PFE inhibited (P < 0.001) MMP-13 expression compared with that detected in chondrocytes stimulated with IL-1β alone except at the lowest PFE concentration tested. In contrast, expression of both MMP-1 and MMP-3 upon stimulation with IL-1β did not increase dramatically (Fig. 1A) although it was more enhanced in samples stimulated with IL-1β than in the controls (P < 0.05). Expression of both MMP-1 and MMP-3 was downregulated by pretreatment with different concentrations of PFE compared with chondrocytes treated with IL-1β alone (P < 0.001). Pretreatment with 50 mg/L PFE almost completely blocked the IL-1β–induced increase in the expression of all 3 MMPs (P < 0.001) by human chondrocytes in vitro (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

PFE inhibits IL-1β–induced expression of MMP-1, -3, and -13 protein in OA chondrocytes in vitro. (A) OA chondrocytes (80% confluent) were treated either with IL-1β (5 μg/L) alone or with IL-1β + PFE (6.25–50 mg/L) for 24 h. (B) Equal loading of proteins was verified by staining a similarly prepared SDS-PAGE gel with the Gel-Code Blue (Pierce). Results shown are representative of 3 independent experiments.

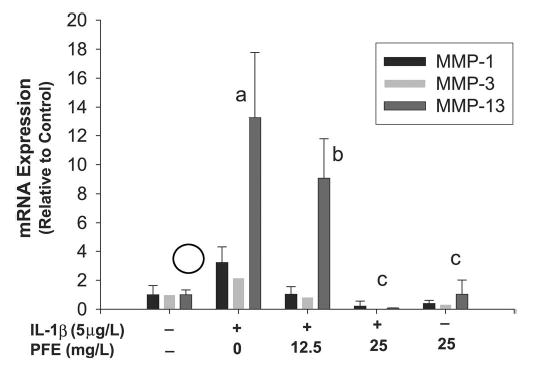

PFE inhibited the IL-1β-induced upregulation of MMP-1, -3, and -13 mRNA levels in OA chondrocytes.

Stimulation with IL-1β upregulated the MMP-1, -3, and -13 mRNA levels by 2.3-, 1.2- and 12.3-fold, respectively (P < 0.05), compared with the levels in untreated control chondrocytes (Fig. 2). Pretreatment with 12.5 mg/L of PFE blocked the IL-1β–induced upregulation of MMP-1, -3 and -13 mRNAs by 68, 62, and 32%, respectively, compared with the mRNA levels in OA chondrocytes stimulated with IL-1β alone (P < 0.05). However, treatment with 25 mg/L PFE completely blocked the IL-1β–induced upregulation of mRNA expression for all 3 MMPs (P < 0.05). This suggests that PFE exerts its inhibitory effect at the transcriptional level and that the low levels of MMP protein in PFE-treated OA chondrocytes (Fig. 1) most likely reflected the inhibition of IL-1β–induced transcription of MMP genes by PFE.

FIGURE 2.

PFE inhibits IL-1β–induced expression of MMP-1, -3, and -13 mRNA in OA chondrocytes in vitro. OA chondrocytes were stimulated with IL-1β (5 μg/L) alone or in combination with PFE (12.5 and 25 mg/L) or PFE alone (25 mg/L) for 24 h. Data are expressed relative to control. Values are means ± SD, n = 3. Means without a common letter differ, P < 0.05.

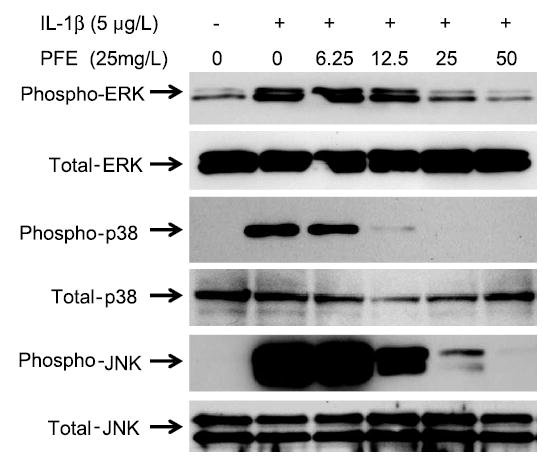

PFE inhibited the IL-1β-induced phosphorylation of ERK, JNK, and p38-MAPK in OA chondrocytes.

IL-1β–induced expression of MMPs in human chondrocytes was shown to be orchestrated by the JNK and p38-MAPK subgroups of the MAPK family of signal transduction molecules. These MAPKs activate transcription factors that bind to the promoter region of MMPs leading to their high levels of expression (33–35). Stimulation of OA chondrocytes with IL-1β for 30 min induced the phosphorylation of ERK, JNK, and p38-MAPK to varying levels; ERK had the smallest, but significant (P < 0.01; Fig. 3) increase, whereas JNK showed the highest level of phosphorylation (P < 0.001) compared with controls. Importantly, pretreatment with PFE (6.25–50 mg/L) differentially inhibited the phosphorylation levels of ERK, JNK, and p38-MAPK in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3). IL-1β–induced phosphorylation of ERK was significantly inhibited only by pretreatment with 25 mg/L (P < 0.01) and 50 mg/L (P < 0.001) PFE, but not by other doses. This suggests that IL-1β–induced phosphorylation of ERK was resistant to the inhibitory effect of PFE in OA chondrocytes. The p38-MAPK protein was also intensely phosphorylated (P < 0.001) in OA chondrocytes stimulated with IL-1β (Fig. 3). Importantly, IL-1β–stimulated phosphorylation of p38-MAPK was significantly inhibited (P < 0.01) by the lowest dose of PFE used and concentrations of 12.5 mg/L or higher suppressed the phosphorylation of p38-MAPK to levels that did not differ from the basal level. These data indicate that IL-1β–stimulated phosphorylation of p38-MAPK in OA chondrocytes was highly susceptible to inhibition by PFE. Phosphorylation of JNK in OA chondrocytes stimulated with IL-1β alone was stronger than the phosphorylation of either ERK or p38-MAPK (P < 0.001), suggesting that JNK was preferentially and strongly activated by IL-1β in OA chondrocytes. Additionally, pretreatment with up to 25 mg/L PFE did not suppress the phosphorylation of JNK compared with controls. Significant inhibition of IL-1β–induced phosphorylation of JNK occurred only in OA chondrocytes pretreated with 50 mg/L of PFE (P < 0.05). Such a differential effect of anthocyanins on cytokine-induced MAPK activation has not been shown in any cell type. Importantly, these concentrations of PFE had no negative effect on the protein levels of any of the MAPKs (Fig. 3), indicating that the inhibitory effect was at the upstream level rather than on the expression level of these kinases. These novel results extend the previous findings substantially and indicate that the reported anti-inflammatory effects of PFE constituents may be related to their ability to modulate the activation of MAPK pathway in the cell.

FIGURE 3.

PFE inhibits the IL-1β–induced activation of MAPKs in OA chondrocytes in vitro. Band intensities of immunoreactive proteins in cells treated with IL-1β were greater than band intensities in controls (P < 0.01 for ERK and P < 0.001 for p38-MAPK and JNK). Phosphorylation of p38-MAPK in IL-1β-stimulated OA chondrocytes was most susceptible to pretreatment with PFE and was inhibited at the lowest concentration used (P < 0.001). Results shown are representative of 2 independent experiments.

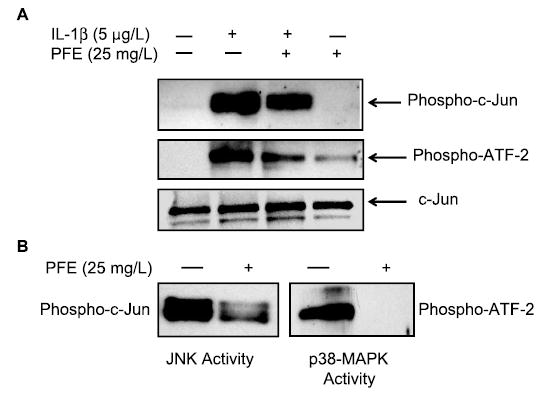

PFE inhibited the IL-1β–induced phosphorylation of c-Jun and ATF-2 in OA chondrocytes.

Several studies showed that c-Jun and ATF-2 are phosphorylated by JNK and p38-MAPK, respectively (30,34). In OA chondrocytes pretreated with PFE, IL-1β–induced phosphorylation of c-Jun and ATF-2 proteins was significantly inhibited compared with the OA chondrocytes stimulated with IL-1β alone (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4A). The control group did not differ from the group treated with PFE alone.

FIGURE 4.

Inhibition of PFE-pretreated IL-1β–stimulated phosphorylation of ATF-2 and c-Jun proteins in OA chondrocytes (A) and of substrate phosphorylating activity of p38-MAPK by PFE in vitro (B). (A) Total cell lysate proteins were resolved by electrophoresis and analyzed by Western blotting using primary antibodies specific for phospho-c-Jun, phospho-ATF-2 and total c-Jun. Band intensities in chondrocytes stimulated with IL-1β were greater than in controls or in cells pretreated with PFE (P < 0.05). (B) Activated JNK and p38-MAPK were immunoprecipitated and their kinasing activity was assayed in the presence or absence of PFE in vitro. Activity of p38-MAPK was totally abolished when PFE was added exogenously (P < 0.0001), whereas that of JNK was inhibited (P < 0.05), but not completely, by PFE in this assay.

PFE inhibited the substrate phosphorylating activity of both p38-MAPK and JNK (Fig. 4B). However, the effect was more pronounced for p38-MAPK activity, which was completely blocked, whereas JNK activity was only partially inhibited (Fig. 4B). Taken together, these results indicate that PFE not only inhibits the activation phase of p38-MAPK but may also inhibit its substrate phosphorylating activity in OA chondrocytes. Furthermore, these results suggest that the inhibitory effect of PFE on MMP production in OA chondrocytes was modulated, at least in part, via inhibition of the p38-MAPK pathway.

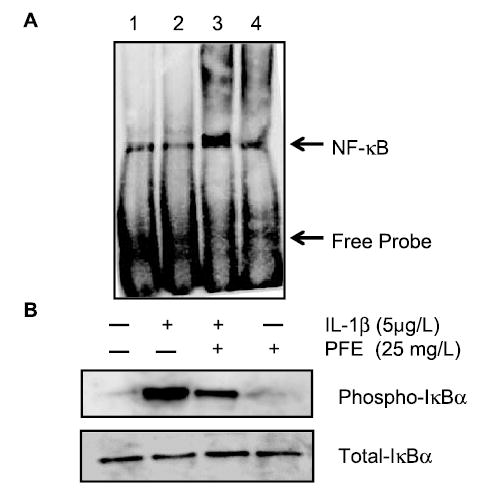

PFE inhibited the DNA binding activity of NF-κB in OA chondrocytes.

NF-κB is a powerful transcription factor regulating the expression of numerous proinflammatory genes including MMPs (36,37). Inhibition of IL-1β–mediated activation of NF-κB was shown to be an essential step in the downregulation of multiple catabolic mediators in cartilage and in cultured human chondrocytes (34,36). We studied the effect of PFE on the IL-1β–induced DNA binding activity of NF-κB in OA chondrocytes using EMSA. Treatment with IL-1β enhanced the DNA binding activity of NF-κB (Lane 3, Fig. 5A), whereas in OA chondrocytes pretreated with 25 mg/L PFE, the IL-1β–induced DNA binding activity of NF-κB was inhibited (Lane-4, Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5.

Inhibition of IL-1β–induced activation and the DNA binding activity of NF-κB (A) and IL-1β-induced phosphorylation of IκBα by PFE in OA chondrocytes (B). (A) DNA binding activity of NF-κB present in nuclear proteins was analyzed using a nonradioactive EMSA method. Position of shifted DNA:protein complexes is marked by an arrow. Lane-1, TNF-α stimulated HeLa cell nuclear protein (positive control); Lane 2, untreated OA chondrocytes (experimental control); Lane 3, IL-1β–treated OA chondrocytes; Lane 4, OA chondrocytes treated with IL-1β + PFE. (B) Total and phosphorylated levels of IκBα were detected in whole-cell lysates of OA chondrocytes treated as above or with PFE alone using Western immunoblotting. Band intensities of phosphorylated IκBα in cells treated with IL-1β alone were greater than in untreated controls or in other cells (P < 0.05). Results shown are representative of 2 independent experiments.

Stimulation with IL-1β increased the phosphorylation of the NF-κB inhibitory protein IκBα (Fig. 5B) above the basal levels (P < 0.05) as was shown previously (30,34,36). However, IL-1β–induced phosphorylation of IκB-α was inhibited (P < 0.05) in OA chondrocytes pretreated with PFE to near basal levels in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 5B). Inhibition of IκBα phosphorylation blocks the ubiquitination and proteasome-mediated degradation of IκBα, resulting in the inhibition of NF-κB. Together these data suggest that the IL-1β–induced inhibition of MMP expression in OA chondrocytes pretreated with PFE is associated with the inhibition of both NF-κB activity and the p38-MAPK/JNK pathways in OA chondrocytes.

DISCUSSION

Pathological induction of MMPs plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of OA and inflammatory diseases. Phytochemicals are potential candidates in an emerging novel and cost-effective approach to block the expression of MMPs for the treatment of many diseases including OA (5,38). In this paper, we describe the cartilage-protective effects exerted by an extract of a widely consumed fruit, pomegranate. Pretreatment of human OA cartilage explants with PFE inhibited IL-1β–induced breakdown of the cartilage extracellular matrix. In similarly treated OA chondrocytes, IL-1β–induced expression of MMPs was also inhibited, indicating that PFE is a potent inhibitor of cartilage matrix degrading enzymes. Our results also showed that the inhibitory effect of PFE was at the transcriptional level because mRNA expression of MMP-1, MMP-3, and MMP-13 was also downregulated in OA chondrocytes. We showed that PFE constituents at low doses selectively inhibit the phosphorylation and activation of p38-MAPK, possibly by inhibiting the activity of upstream MAP kinase kinases, and also are potent inhibitors of the p38-MAPK activity. Thus, treatment with PFE affects both phases of IL-1β–induced p38-MAPK activation in OA chondrocytes. We showed further that inhibition of p38-MAPK and JNK activation by PFE correlated with the reduced accumulation of downstream target transcription factors ATF-2 and c-Jun required for the optimum expression of MMPs and other inflammatory mediators. Additionally, PFE also blocked the IL-1β–induced activation and DNA binding activity of NF-κB by inhibiting the phosphorylation of its inhibitor IκB-α in human OA chondrocytes. These findings describe a new activity for PFE, namely, cartilage/chondroprotection, in addition to its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties previously described (13,14).

MMPs are a family of enzymes that mediate a wide variety of functions in tissue remodeling including the turnover, degradation, catabolism, and destruction of the extracellular matrix (39). The uncontrolled regulation and enhanced expression of MMPs is closely associated with the progression of arthritis (39,40). Collagenases (especially, MMP-1 and MMP-13) are enzymes that possess higher affinity to cleave the triple-helical structure of type-II collagen, and their increased levels in OA points to a role in cartilage degradation (41,42). Our findings that IL-1β preferentially upregulated the expression of MMP-13 compared with MMP-1 and MMP-3 and that PFE was highly effective in inhibiting the IL-1β–induced upregulation without negatively affecting the chondrocyte viability or the integrity of the cartilage ECM are novel and have not been reported previously. It is important to point this out because MMPs are not generally present in a normal physiological state; rather, they are restricted to pathological conditions including OA (4,42). Thus, compounds capable of suppressing MMP expression may have applications in arthritis therapy. Interestingly, pretreatment with PFE also inhibited the basal levels of MMPs spontaneously produced by OA chondrocytes, suggesting that consumption of PFE might be effective in suppressing the endogenous levels of these enzymes in an arthritic joint as well. However, this will depend on the bioavailability of the active constituents in PFE (not yet identified) in the joint, which has not yet been explored.

PFE is a rich source of anthocyanins, a class of water-soluble bioavailable flavonoids that are common in the human diet and readily absorbed in the alimentary tract (43). A study by Garbacki et al. (23) using human chondrocytes showed that anthocyanins had a positive regulatory effect on proteoglycan and collagen-II synthesis; however, its chondroprotective mechanism(s) was not elucidated in that study. Although PFE has not been studied extensively for its potential benefits in musculoskeletal diseases, its recent use as adjunct therapy in cardiovascular patients has opened venues for further exploiting its medicinal benefits (44).

High-level expression of MMPs in arthritic joints results from the activation of a tightly regulated and synchronized signaling cascade activated by inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α involving the p38-MAPK and JNK enzymes (30,34). The activation and binding of activator protein-1 to the promoters of MMP genes is essential for their optimum expression, and inhibition of p38-MAPK and JNK activity interferes with this sequence of events (45,46). PFE inhibited the expression of MMPs in OA chondrocytes by inhibiting the activation of p-38 MAPK and JNK, thereby reducing the available pool of activated c-Jun and ATF-2. These results concur with previous findings in which inhibition of p-38MAPK and JNK abolished joint destruction in animal models of arthritis (32,45). Interestingly, this is the first study demonstrating the inhibitory effect of PFE on IL-1β–induced p38-MAPK and JNK activation; hence, its possible beneficial effects in chondrocyte biology and cartilage homeostasis are implicit.

The NF-κB/Rel transcription family, by nuclear translocation of its cytoplasmic complexes, plays a central role in inflammation through its ability to induce transcription of proinflammatory genes (36,47). Within chondrocytes, the NF-κB pathway is indispensable to the expression of MMP-1, -3, and -13 and other inflammatory mediators (33,39,40,48). Because it is an oxidant-sensitive transcription factor, its inhibition in different in vitro and in vivo experimental settings was shown to inhibit ECM resorption and disease progression in the affected joints (49–51). Because PFE constituents are potent antioxidants, inhibition of IL-1β–induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and ROS-mediated oxidative stress in human chondrocytes in vitro may also have played a role in NF-κB inhibition. However, this aspect was not investigated in the present study.

In summary, we showed that pretreatment of human OA chondrocytes with PFE inhibited IL-1β–induced expression of MMPs 1, 3, and 13, which are classical markers of inflammation and cartilage degradation in arthritic joints. Thus, our results suggest that PFE constituents may possess anticollagenolytic properties and may be of value in inhibiting the induction and/or pathogenesis of OA. Further investigations are required to establish the validity of this hypothesis. Additionally, our data suggest that PFE or compounds derived from it may be beneficial in maintaining joint function and could be potential candidates for adjunct/complementary therapy in joint disorders. Therefore, an in-depth study to define the bioavailability of active agent(s) in PFE capable of affording cartilage and chondroprotective effect in vivo is warranted.

Footnotes

Supported in part by grants AR-48782 from United States Public Health Service/National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Arthritis and Musculo-skeletal and Skin Diseases and AT-002258 from USPHS/NIH/National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. N.W. is supported by the USPHS/NIH/NIAMS training grant AR-07505.

Abbreviations used: ATF-2, activated transcription factor-2; DMMB, 1,9-imethylmethylene blue; ECM, extracellular matrix; EMSA, electrophoretic mobility shift assay; ERK, extracellular regulated kinase; GAG, glycosaminoglycan; IκBα, inhibitor of κBα; IL, interleukin; JNK, c-Jun-N-terminal kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; OA, osteoarthritis; PFE, pomegranate fruit extract; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TPA, 12-o-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.van den Berg WB. Pathophysiology of osteoarthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2000;67:555–556. doi: 10.1016/s1297-319x(00)00216-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malemud CJ, Islam N, Haqqi TM. Pathophysiological mechanisms in osteoarthritis lead to novel therapeutic strategies. Cells Tissues Organs. 2003;174:34–48. doi: 10.1159/000070573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yelin E, Callahan LF. The economic cost and social and psychological impact of musculoskeletal conditions. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1351–1362. doi: 10.1002/art.1780381002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mix KS, Mengshol JA, Benbow U, Vincenti MP, Sporn MB, Brinkerhoff CE. A synthetic triterpenoid selectively inhibits the induction of matrix metalloproteinases 1 and 13 by inflammatory cytokines. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1096–1104. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200105)44:5<1096::AID-ANR190>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmed S, Wang N, Lalonde M, Haqqi TM. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) differentially inhibits interleukin-1β-induced expression of matrix metalloproteinase-1 and -13 in human chondrocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308:767–773. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.059220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van den Berg WB. Joint inflammation and cartilage destruction may occur uncoupled. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 1998;20:149–164. doi: 10.1007/BF00832004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldrosen HM, Straus SE. Complementary and alternative medicine: assessing the evidence for immunological benefits. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:912–921. doi: 10.1038/nri1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halliwell B, Rafter J, Jenner A. Health promotion by flavonoids, tocopherols, tocotrienols, and other phenols: direct or indirect effects? Antioxidant or not? Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:268S–276S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.1.268S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atrs IC, Hollman PC. Polyphenols and disease risk in epidemiologic studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:317S–325S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.1.317S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williamson G, Manach C. Bioavailability and bioefficacy of polyphenols in humans. II Reviews of 93 intervention studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:243S–255S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.1.243S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curtis CL, Harwood JL, Dent CM, Caterson B. Biological basis for the benefit of nutraceutical supplementation in arthritis. Drug Disc Today. 2004;9:165–172. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(03)02980-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Longtin R. The pomegranate: nature’s power fruit? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:346–348. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.5.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gil MI, Tomas-Barberan FA, Hess-Pierce B, Holcraft DM, Kedar AA. Antioxidant activity of pomegranate juice and its relationship with phenolic composition and processing. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;10:4581–4589. doi: 10.1021/jf000404a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Afaq F, Malik A, Syed D, Maes D, Matsui MS, Mukhtar H. Pomegranate fruit extract modulates UVB-mediated phosphorylation of mitogen activated protein kinases: activation of nuclear factor kappa B in normal human epidermal keratinocytes. Photochem Photobiol. 2005;81:38–45. doi: 10.1562/2004-08-06-RA-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Afaq F, Saleem M, Krueger CG, Reed JD, Mukhtar H. Anthocyanins- and hydrolysable tannin-rich pomegranate fruit extract modulates MAPK and NF-κB pathway and inhibits skin tumorigenesis in CD-1 mice. Int J Cancer. 2005;113:423–433. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawaii S, Lansky EP. Differentiation-promoting activity of pomegranate (Punica granatum) fruit extracts in HL-60 human promyelocytic leukemia cells. J Med Food. 2004;7:13–18. doi: 10.1089/109662004322984644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aviram M, Dornfield L, Coleman R. Pomegranate juice flavonoids inhibit low-density lipoprotein oxidation and cardiovascular diseases: studies in atherosclerotic mice and in humans. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 2002;28:49–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsuda T, Horio F, Osawa T. Cyanidin 3-O-beta-D-glucoside suppresses nitric oxide production during zymogen treatment in rats. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol. 2002;48:305–310. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.48.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Youdim KA, McDonald J, Kalt W, Joseph JA. Potential role of dietary flavonoids in reducing microvascular endothelium vulnerability to oxidative and inflammatory insults. J Nutr Biochem. 2002;13:282–288. doi: 10.1016/s0955-2863(01)00221-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Talavera S, Felgines C, Texier O, Besson C, Lamaison JL, Rémésy C. Anthocyanins are efficiently absorbed from the stomach in anaesthetized rats. J Nutr. 2003;133:4178–4182. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.12.4178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noda Y, Kaneyuki T, Mori A, Packer L. Antioxidant activities of pomegranate fruit extract and its anthocyanidins: delphinidin, cyanidin, and pelargonidin. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:166–171. doi: 10.1021/jf0108765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seeram NP, Nair MG. Inhibition of lipid peroxidation and structure-activity related studies of the dietary constituent’s anthocyanins, anthocyanidins, and catechins. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:5308–5312. doi: 10.1021/jf025671q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garbacki N, Angenot L, Bassleer C, Damas J, Tits M. Effects of prodelphinidins isolated from Ribes nigrum on chondrocytes metabolism and COX activity. Arch Pharmacol. 2002;365:434–441. doi: 10.1007/s00210-002-0553-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin S, Favot L, Matz R, Lugnier C, Andriantsitohaina R. Delphinidin inhibits endothelial cell proliferation and cell cycle progression through a transient activation of ERK-1/2. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;65:669–675. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01568-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hou DX, Kai K, Li JJ, Lin S, Terahara N, Wakamatsu M, Fujii M, Young MR, Colburn N. Anthocyanidins inhibit activator protein 1 activity and cell transformation: structure-activity relationship and molecular mechanisms. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:29–36. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Revilla E, Jose-Maria R, Martin-Ortega G. Comparison of several procedures used for the extraction of anthocyanins from red grapes. J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46:4592–4597. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmed S, Rahman A, Hasnain A, Lalonde M, Goldberg VM, Haqqi TM. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits the IL-1β-induced activity and expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and nitric oxide synthase-2 in human chondrocytes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:1097–1105. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Islam S, Islam N, Kermode T, Johnstone B, Mukhtar H, Moskowitz RW, Haqqi TM. Involvement of caspase-3 in epigallocatechin-3-gallate-mediated apoptosis of human chondrosarcoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;270:793–797. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farndale RW, Buttle DJ, Barrett AJ. Improved quantitation and discrimination of sulphated glycosaminoglycans by use of dimethylmethylene blue. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1986;883:173–177. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(86)90306-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmed S, Rahman A, Hasnain A, Goldberg VM, Haqqi TM. Phenyl-N-tert-butylnitrone down-regulates interleukin-1β-stimulated matrix metalloproteinase-13 gene expression in human chondrocytes: suppression of c-Jun NH2 terminal kinase, p38-mitogen-activated protein kinase and activating protein-1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305:981–988. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.048611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kraan PM, van den Berg WB. Anabolic and destructive mediators in osteoarthritis. Cur Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2003;3:205–211. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200005000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Han Z, Boyle DL, Chang L, Bennett B, Karin M, Yang L, Manning AM, Firestein GS. c-Jun N-terminal kinase is required for metalloproteinase expression and joint destruction in inflammatory arthritis. J Clin Investig. 2001;108:73–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI12466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berenbaum F. Signaling transduction: target in osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16:616–622. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000133663.37352.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mengshol JA, Vincenti MP, Coon CI, Barchowsky A, Brinkerhoff CE. Interleukin-1 induction of collagenase 3 (matrix metalloproteinase 13) gene expression in chondrocytes requires p38, c-Jun n-terminal kinase and nuclear factor kappaB. Differential regulation of collagenase 1 and collagenase 3. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:801–811. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200004)43:4<801::AID-ANR10>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vincenti MP, Brinkerhoff CE. Transcriptional regulation of collagenase (MMP-1, MMP-13) genes in arthritis: integration of complex signaling pathways for the recruitment of gene-specific transcription factors. Arthritis Res. 2002;4:157–164. doi: 10.1186/ar401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh R, Ahmed S, Islam N, Goldberg VM, Haqqi TM. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits interleukin-1β-induced expression of nitric oxide synthase and production of nitric oxide in human chondrocytes: suppression of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB/p65) activation by inhibiting IB-degradation. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2079–2086. doi: 10.1002/art.10443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Firestein GS. NF-κB: holy grail for rheumatoid arthritis? Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2381–2386. doi: 10.1002/art.20468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corps AN, Curry VA, Buttle DJ, Hazleman BL, Riley GP. Inhibition of interleukin-1beta-stimulated collagenase and stromelysin expression in human tendon fibroblasts by epigallocatechin gallate ester. Matrix Biol. 2004;23:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brinkerhoff CE, Matrisian LM. Matrix metalloproteinases: a tail of a frog that became a prince. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nrm763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Visse R, Nagase H. Matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases: structure, function and biochemistry. Circ Res. 2003;92:827–839. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000070112.80711.3D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Billinghurst RC, Wu W, Ionescu M, Reiner A, Dahlberg L, Chen J, van Wart H, Poole AR. Comparison of the degradation of type II collagen and proteoglycan in nasal and articular cartilages induced by interleukin-1 and the selective inhibition of type II collagen cleavage by collagenase. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:664–672. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200003)43:3<664::AID-ANR24>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vincenti MP, Coon CI, Mengshol JA, Yocum S, Cepnois A, Brinckerhoff CE. Cloning of the gene for interstitial collagenase-3 (matrix metalloproteinase-13) from rabbit synovial fibroblasts: differential expression with collagenase-1 (matrix metalloproteinase-1) Biochem J. 1998;331:341–346. doi: 10.1042/bj3310341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kowalczyk E, Krzensinski P, Kura M, Szmigiel B, Blaszczyk J. Anthocyanins in medicine. Pol J Pharmacol. 2003;55:699–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aviram M, Dornfeld L, Rosenblat M, Volkova N, Kaplan M, Coleman R, Hayek T, Presser D, Fuhrman B. Pomegranate juice consumption reduces oxidative stress atherogenic modifications to LDL, and platelet aggregation: studies in humans and in atherosclerotic apolipoprotein deficient mice. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:1062–1076. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.5.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shiozawa S, Shimizu K, Tanaka K, Hino K. Studies on the contribution of cfos/AP-1 to arthritic joint destruction. J Clin Investig. 1997;99:1210–1216. doi: 10.1172/JCI119277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trenies I, Paterson HF, Hooper S, Wilson R, Marshall CJ. Activated MEK stimulates expression of AP-1 components independently of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-kinase) but requires a PI3-kinase to stimulate DNA synthesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:321–329. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barnes PJ, Karin M. Nuclear factor kappaB: a pivotal transcription factor in chronic inflammatory diseases. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1066–1071. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704103361506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Makarov SS. NF-κB as a therapeutic target in chronic inflammation: recent advances. Mol Med Today. 2000;6:441–446. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(00)01814-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsao PW, Suzuki T, Totsuka R, Murata T, Takagi T, Ohmachi Y, Fujimura H, Takate I. The effect of dexamethasone on the expression of activated NF-κB in adjuvant arthritis. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;83:173–178. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tiku ML, Shah R, Alison GT. Evidence linking chondrocytes lipid peroxidation to cartilage matrix protein degradation: possible role in cartilage aging and the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:20069–20075. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M907604199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tiku ML, Gupta S, Deshmukh DR. Aggrecan degradation in chondrocytes is mediated by reactive oxygen species and protected by antioxidants. Free Radic Res. 1999;30:395–405. doi: 10.1080/10715769900300431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]