Abstract

DNA replication initiation in prokaryotes and eukaryotes requires the recruitment and loading of a helicase at the replication origin. To subsequently unwind the double-stranded DNA, the helicase must be properly positioned on the separated DNA strands. Several studies have revealed similarities and differences in the mechanisms used by different autonomously replicating DNA elements (replicons) for recruitment and activation of the appropriate helicase. Of particular interest are plasmid replicons that are adapted for replication in diverse bacterial hosts and are therefore intriguingly able to exploit the helicases of distantly related bacterial species. The different molecular mechanisms by which replicons recruit and load helicases are only just beginning to be understood.

Introduction

The replication of eukaryotic and prokaryotic chromosomes, viruses and bacterial plasmids involves several analogous events and similarities in replisome architecture. For many systems, it has been demonstrated that specific initiation proteins, including bacterial DnaA protein, phage λ O protein, SV40 T antigen, plasmid replication initiation proteins (generally termed Rep) and the eukaryotic origin recognition complex (ORC), form complexes at the origin that serve as platforms for subsequent DNA replication initiation events. Despite certain similarities, the specific mechanism for replication initiation of a given replicon is dependent on both the structure of the replication origin and the nature of the replication initiation protein. The replication of extra-chromosomal replicons, such as plasmids, phages and viruses, is generally limited to a single host or a few closely related hosts (narrow host range). However, promiscuous plasmids of bacteria are able to replicate and maintain themselves in many distantly related bacterial species (broad host range). Consequently, versatile interactions of plasmid-encoded proteins and replication origins with host-specific replication factors might determine the mode of broad-host-range replicon initiation.

Origin structure and opening

The origins of prokaryotic and some eukaryotic replicons such as DNA viruses and Saccharomyces cerevisiae possess characteristic functional elements, including specific binding sites for the appropriate initiation protein and an AT-rich region where DNA duplex destabilization occurs. Plasmid origins usually contain multiple binding sites (iterons) for the plasmid-specific replication initiation protein as well as one or more binding sites for the host replication initiation protein, DnaA (DnaA boxes; Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Structural organization of some prokaryotic origins. The multiple repeat sequences (iterons), AT-rich and GC-rich regions, and DnaA box sequences are indicated. (Maps are not drawn to scale.)

Several lines of evidence suggest that these structural elements of the origin are employed for broad-host-range plasmid replication and maintenance in different host bacteria species. For example, the minimal origin of the broad-host-range plasmid RK2 (oriV; Fig. 1) possesses five iterons and is functional in Escherichia coli. However, the presence of three additional iterons stabilizes RK2 plasmid maintenance in Pseudomonas putida (Schmidhauser et al., 1983). In addition, the region with four DnaA boxes is essential for RK2 replication in E. coli, but is dispensable for replication of the plasmid in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Shah et al., 1995; Doran et al., 1999). In the E. coli chromosome, the replication origin (oriC) contains five DnaA box sequences (Fig. 1).

The binding of multiple DnaA molecules in the presence of the histone-like HU protein and the site-specific DNA-binding protein IHF (integration host factor) results in destabilization of the duplex DNA within the nearby AT-rich sequences of the oriC of E. coli (Messer et al., 2001). Origin opening of the narrow-host-range plasmids P1, F, R6K and pSC101 requires, in addition to E. coli DnaA, HU and/or IHF proteins, the binding of plasmid-encoded replication initiation proteins (Mukhopadhyay et al., 1993; Kawasaki et al., 1996; Lu et al., 1998; Park et al., 1998; Kruger et al., 2001; Sharma et al., 2001). Similarly, the formation of an open complex at the replication origin of the broad-host-range plasmid RK2 by the plasmid-encoded TrfA initiation protein requires E. coli HU, and is stabilized by E. coli DnaA (Konieczny et al., 1997).

In contrast to the chromosomal oriC, but similar to bacteriophage λ, plasmid origins do not require ATP for open complex formation (Schnos et al., 1988; Mukhopadhyay et al., 1993; Kawasaki et al., 1996; Lu et al., 1998; Park et al., 1998). A basis for this lack of dependence on ATP might be the intrinsic DNA curvature of these origins as well as origin bending, induced in an ATP-independent mode, by the complex of the plasmid-encoded Rep protein and the host HU or IHF (Stenzel et al., 1991; Doran et al., 1998; Lu et al., 1998; Komori et al., 1999; Sharma et al., 2001).

DnaB and other replicative helicases

The DnaB protein, the major replicative DNA helicase in E. coli (LeBowitz & McMacken, 1986), is a member of the hexameric DNA helicase family, which includes the T4 and T7 DNA helicases and plasmid RSF1010-encoded RepA, as well as the SV40 T antigen and the human MCM (minichromosome maintenance) protein (Patel & Picha, 2000). Although no sequence identity has yet been defined, these helicases form a ring structure with a central opening and are associated with DNA replication complexes. Mammalian MCM helicase is a complex of several different but related peptides. Interestingly, it was recently shown that the Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum MCM protein can form heptameric rings (Yu et al., 2002). Several lines of evidence suggest that DNA passes through the central opening of the helicase ring, although an alternative model of DNA wrapping around the outside of the helicase ring has also been proposed (Patel & Picha, 2000).

E. coli DnaB is a multifunctional enzyme with a number of distinct activities including DNA binding, ATP hydrolysis, DNA unwinding and the stimulation of the DnaG primase for primer synthesis, which is required to start the polymerization reaction by the DNA polymerase holoenzyme. DnaB interacts with a number of proteins, including E. coli DnaA (Marszalek & Kaguni, 1994), DnaC (Wickner & Hurwitz, 1975), DnaG primase (Lu et al., 1996; Tougu & Marians, 1996) and the τ subunit of DNA polymerase (Kim et al., 1996), as well as the plasmid-encoded replication initiation proteins RepA of pSC101 (Datta et al., 1999), π of R6K (Ratnakar et al., 1996) and TrfA of RK2 (Pacek et al., 2001). The E. coli DnaB hexamer is present in vivo in a protein complex with six monomers of the DnaC protein and six ATP molecules (Wickner & Hurwitz, 1975; Lanka & Schuster, 1983; Fig. 2).

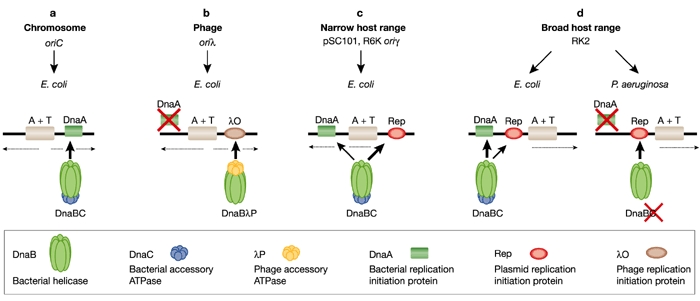

Figure 2.

Models for helicase recruitment and loading at plasmid, phage and bacterial chromosomal origins. Protein requirements and interactions required for helicase recruitment and loading are depicted. Thick arrows indicate the crucial interactions; dotted arrows indicate the direction of replication. (A) A physical interaction between E. coli DnaA and DnaB helicase as well as the activity of an accessory DnaC ATPase are essential for delivering the helicase to E. coli oriC. (B) During bacteriophage λ replication, the role of DnaC is performed by the λP protein, which binds the E. coli DnaB helicase and delivers it to oriλ by means of an interaction with the λO protein. (C) In addition to E. coli DnaA and DnaC proteins, helicase recruitment at narrow-host-range plasmid origins requires plasmid-specific replication initiation proteins (Rep). (D) Alternative mechanisms for helicase recruitment and loading at the origin of the broad-host-range plasmid RK2. The host-specific DnaA–DnaB interaction used for helicase recruitment at the DnaA boxes of the RK2 plasmid origin is applicable to plasmid replication in E. coli. In P. aeruginosa, helicase is recruited and loaded onto the RK2 origin in a DnaA- and DnaC-independent mode, through a specific interaction with the plasmid TrfA-44 replication initiation protein.

E. coli DnaB helicase recruitment and loading

The E. coli DnaB helicase binds to single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) in an ATP-dependent manner. However, this activity alone is not sufficient for helicase loading at a replication origin because the DnaB hexamer by itself has no affinity for ssDNA bound by SSB (single- stranded binding protein). Thus, entry of the DnaB helicase complex into the unwound oriC depends on additional protein factors, and the mechanism behind this event is not fully understood. Chemical crosslinking, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays and monoclonal antibody interference studies have shown that a physical interaction between E. coli DnaA and DnaB is essential for delivering the helicase to oriC (Marszalek & Kaguni, 1994). The loading of DnaB probably depends not only on DnaA binding to the DnaA boxes present in the E. coli oriC sequence (Fig. 2A) but also on DnaA binding to the open region of the origin, which is then stabilized for subsequent helicase loading (Speck & Messer, 2001). A specific physical interaction between DnaA and DnaB was also shown to be crucial during plasmid RK2 replication initiation in E. coli (Konieczny & Helinski, 1997; Fig. 2D). This DnaA–DnaB complex was found at the DnaA box region of oriV, which is separated by more than 200 base pairs (bp) from the RK2 origin opening and has a strict DnaA box sequence requirement for stable formation (Pacek et al., 2001).

In addition to the interaction between DnaB and DnaA, the helicase accessory ATPase protein, DnaC, is also required for helicase complex formation and helicase loading at E. coli oriC, as well as at several plasmid origins including RK2 (Konieczny & Helinski, 1997), R6K (Lu et al., 1998) and pSC101 (Datta et al., 1999). The T4 gp59 and B. subtilis DnaI proteins have a role similar to that of DnaC, serving as helicase loading factors during bacteriophage T4 and B. subtilis DNA replication initiation, respectively (Kreuzer & Morrical, 1994; Imai et al., 2000). Two eukaryotic proteins, Cdc6 and Cdt1, the latter recently identified as a novel component of the pre-replication complex, have been proposed to recruit the MCM complex in Xenopus and Saccharomyces (Baker & Bell, 1998; Bell & Dutta, 2002). During the replication of bacteriophage λ, the role of DnaC is performed by the λP protein, which is also an ATPase but shares no sequence similarity with DnaC. λP protein binds the E. coli DnaB helicase and delivers it to the λ origin (oriλ) by means of an interaction with the λO protein (Dodson et al., 1985; Fig. 2B). After the helicase complex has been formed at oriλ, it must be remodelled by the concerted actions of the E. coli chaperones DnaK, DnaJ and GrpE (Konieczny & Zylicz, 1999). At this step, DnaB is released from a tight interaction with λP. The requirement for molecular chaperones is decreased by a mutation in the λP gene, which weakens the interaction between the λP protein and the DnaB helicase (Konieczny & Marszalek, 1995).

The detailed molecular mechanism of helicase loading onto ssDNA is not fully understood. It has been shown that ssDNA-binding activity of λP and DnaC is involved in DnaB loading (Learn et al., 1997), and also that DnaC is released with concomitant hydrolysis of ATP during helicase loading onto oriC (Funnell et al., 1987; Allen & Kornberg, 1991). Recently, it was proposed that DnaC is a dual ATP/ADP switch protein, with DnaB and ssDNA triggering ATP hydrolysis by DnaC (Davey et al., 2002). Surprisingly, ATP is not required for the loading of DnaB by DnaC onto ssDNA, and the model proposes that DnaC–ATP loads the helicase onto oriC, but that conversion to DnaC–ADP is required before the helicase is active (Davey et al., 2002).

During replication initiation of plasmid RK2 in E. coli, the DnaA protein directs DnaB, in complex with DnaC, to the DnaA boxes in oriV of RK2. However, the helicase complex fails to unwind the template unless the plasmid initiation protein TrfA is also present (Konieczny & Helinski, 1997). It has been proposed that the helicase is repositioned from the DnaA boxes onto the AT-rich region via a direct contact with TrfA (Pacek et al., 2001). The loading of DnaB onto the ssDNA depends on the precise positioning of the DnaA boxes at oriV, as was shown by the disruption of helicase loading by the insertion of 6 bp between the DnaA boxes and the iterons at oriV, although opening was normal (Doran et al., 1998). Interactions between E. coli DnaB and plasmid Rep proteins have also been reported for the plasmids R6K (Ratnakar et al., 1996) and pSC101 (Datta et al., 1999), and these have been shown to be crucial for initial helicase complex formation at these plasmid origins. A mutant form of the DnaB protein that does not interact with pSC101 RepA fails to activate replication initiation at this origin. However, the mutant maintains its ability to support replication initiation at oriC (Datta et al., 1999). The plasmid R6K π protein and pSC101 RepA have also been shown to interact with the E. coli DnaA initiator (Lu et al., 1998; Sharma et al., 2001), which suggests a complex interaction involving the plasmid Rep protein in the formation of the prepriming complex, helicase loading, and activation.

Species-specific helicase recruitment and loading?

An intriguing question pertaining to DNA replication is whether or not the mechanism for helicase recruitment and loading described for E. coli oriC is also responsible for replication initiation of chromosomal and plasmid origins in other bacterial species. E. coli has traditionally been used as a model organism, but it is not clear whether these studies really do provide universal rules for all prokaryotes. This limitation can be overcome by studying promiscuous plasmids, which provide unique systems for exploring species-dependent replication mechanisms. Genetic and biochemical studies have suggested that these replicons have developed two major strategies to facilitate DNA replication in different genetic backgrounds: (1) initiation independent of host-DNA replication initiation factors, and (2) initiation dependent on versatile communication between plasmid and host-DNA replication initiation factors. Broad-host-range plasmids belonging to the IncQ incompatibility group (for example RSF1010) employ the first strategy by encoding three replication proteins that obviate the need for certain host proteins. The product of the repA gene of RSF1010 was found to have ssDNA-dependent ATPase and DNA helicase activity (Scherzinger et al., 1997), the repC product binds to the iterons and opens the origin region, creating the entry site for the RepA helicase (Scherzinger et al., 1991), and the repB product encodes a primase.

Broad-host-range plasmids belonging to the IncP group (e.g. RK2) rely on replication proteins from the host cell, and might therefore use a helicase loading mechanism adapted to the genetic background of the specific host bacterium. Recent results indicate that this is so (Caspi et al., 2001). In vitro experiments with purified helicase from E. coli, P. putida and P. aeruginosa revealed that, unlike the E. coli DnaB helicase, both Pseudomonas helicases could be delivered and activated at the RK2 oriV in the absence of a DnaC-like ATPase accessory protein (Fig. 2D). Further versatility is provided by two forms of the RK2 initiation protein (TrfA; 44 and 33 kDa), which are generated by alternative in-frame translational start sites (Kornacki et al., 1984; Shingler & Thomas, 1984). The requirement for each of these forms is hostspecific. Either form of the TrfA protein binds to the iterons located at oriV (Perri et al., 1991) and opens the origin at the AT-rich region (Caspi et al., 2001). Both are also functional in E. coli and P. putida, but only the 44-kDa protein is active in P. aeruginosa (Durland & Helinski, 1987; Fang & Helinski, 1991). Consistent with these observations are in vitro experiments showing that E. coli or P. putida DnaB is active with either TrfA-33 or TrfA-44, whereas P. aeruginosa DnaB specifically requires TrfA-44 for helicase complex formation and template unwinding (Caspi et al., 2001). The molecular basis for this difference has recently been elucidated (Y. Jiang, M. Pacek, D.R. Helinski, I.K. and A. Toukdarian, unpublished observations). Size-exclusion chromatography and helicase-activity assays with altered oriV templates showed that neither DnaA nor the DnaA box sequences were required for the formation and activity of the Pseudomonas helicase complex at RK2 oriV. Furthermore, biospecific interaction analysis with BIAcore revealed that Pseudomonas helicases form complexes with TrfA-44 but not with TrfA-33 bound to the oriV iterons. The deletion of a putative helical region at the amino terminus of TrfA-44 completely abolished Pseudomonas helicase complex formation at the iterons (Z. Zhong, D. Helinski and A. Toukdarian, unpublished observations).

These results suggest that, depending on the bacterial host, RK2 uses either a DnaA-dependent or a DnaA-independent pathway for helicase recruitment and activation (Fig. 2D). The DnaA-dependent pathway is specific for RK2 replication initiation in E. coli. The second pathway, employed in P. putida and P. aeruginosa, involves helicase recruitment through its interaction with TrfA-44 bound to iterons. Moreover, for the Pseudomonas sp. helicases, the host DnaA protein is not essential for helicase complex formation and activity at oriV.

Conclusions

Although the analysis of helicase recruitment is still limited to a few bacterial species and a few plasmid replicons, some general conclusions can already be drawn. It is obvious that replicons use self-specific mechanisms for helicase recruitment and loading (Fig. 2), and it has been found that in some cases the helicase is recruited and loaded at the replication origin by an interaction with the DnaA protein bound to DnaA boxes. This mechanism requires an accessory DnaC ATPase and is essential during the initiation of chromosomal replication in E. coli (Fig. 2A). It might also be used by some plasmid replicons (Fig. 2C and D). In addition to E. coli DnaA and DnaC proteins, helicase recruitment at plasmid origins (namely P1, R6K, pSC101 and RK2) requires plasmidspecific replication initiation proteins. A different mechanism is used during bacteriophage λ DNA replication, in which a phage-encoded accessory ATPase (λP protein) has a crucial role in recruitment of the host helicase (Fig. 2B). In a third mechanism, an accessory ATPase is not required and loading of the helicase is solely dependent on interaction with the replication initiation protein (namely plasmid RK2 replication in Pseudomonas sp.; Fig. 2D).

Interestingly, certain broad-host-range plasmids (such as RK2) can use host-specific pathways for helicase recruitment and loading. Plasmid RK2 shows versatility in terms of its requirement for certain origin structural elements (DnaA boxes and number of iterons) in various bacterial hosts. Another important factor is the nature of the protein interactions between the two forms of the RK2 replication initiation protein and the host replication machinery. Recruitment of the helicase through the N-terminal domain uniquely present in the larger form of the plasmid-replication initiation protein is crucial in P. aeruginosa but has no role in helicase recruitment in E. coli. Similarly, the necessity of host-specific DnaA–DnaB interactions used for helicase recruitment at the plasmid origin depends on the bacterial species.

It is evident that the structure of the origin and the properties of the replication initiation protein contribute to the mechanism of helicase recruitment. Furthermore, helicase can be loaded onto a replication origin via different interactions. Genetic background and probably other conditional factors influence the way in which the helicase is recruited. Conceivably, alternative pathways might exist in the same bacterium under different growth conditions. It is of particular interest to determine the factors that affect replication initiation specificity.

Igor Konieczny is the recipient of an EMBO Young Investigator Award.

Acknowledgments

I thank D. Helinski and A. Toukdarian for a critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by Polish State Committee for Scientific Research Grant 3P04A01422 and the EMBO/HHMI Young Investigator Programme.

References

- Allen G.C. Jr & Kornberg A. (1991) Fine balance in the regulation of DnaB helicase by DnaC protein in replication in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem., 266, 22096–22101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker T.A. & Bell S.P. (1998) Polymerases and the replisome: machines within machines. Cell, 92, 295–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell S.P. & Dutta A. (2002) DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 71, 333–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi R. et al. (2001) A broad host range replicon with different requirements for replication initiation in three bacterial species. EMBO J., 20, 3262–3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta H.J., Khatri G.S. & Bastia D. (1999) Mechanism of recruitment of DnaB helicase to the replication origin of the plasmid pSC101. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 73–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey M.J., Fang L., McInerney P., Georgescu R.E. & O'Donnell M. (2002) The DnaC helicase loader is a dual ATP/ADP switch protein. EMBO J., 21, 3148–3159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodson M., Roberts J., McMacken R. & Echols H. (1985) Specialized nucleoprotein structures at the origin of replication of bacteriophage lambda: complexes with lambda O protein and with lambda O, lambda P, and Escherichia coli DnaB proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 82, 4678–4682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doran K.S., Helinski D.R. & Konieczny I. (1999) Host-dependent requirement for specific DnaA boxes for plasmid RK2 replication. Mol. Microbiol., 33, 490–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doran K.S., Konieczny I. & Helinski D.R. (1998) Replication origin of the broad host range plasmid RK2: positioning of various motifs is critical for initiation of replication. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 8447–8453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durland R.H. & Helinski D.R. (1987) The sequence encoding the 43-kilodalton trfA protein is required for efficient replication or maintenance of minimal RK2 replicons in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Plasmid, 18, 164–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang F.C. & Helinski D.R. (1991) Broad-host-range properties of plasmid RK2: importance of overlapping genes encoding the plasmid replication initiation protein TrfA. J. Bacteriol., 173, 5861–5868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funnell B.E., Baker T.A. & Kornberg A. (1987) In vitro assembly of a prepriming complex at the origin of the Escherichia coli chromosome. J. Biol. Chem., 262, 10327–10334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai Y. et al. (2000) Subcellular localization of Dna-initiation proteins of Bacillus subtilis: evidence that chromosome replication begins at either edge of the nucleoids. Mol. Microbiol., 36, 1037–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki Y., Matsunaga F., Kano Y., Yura T. & Wada C. (1996) The localized melting of mini-F origin by the combined action of the mini-F initiator protein (RepE) and HU and DnaA of Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet., 253, 42–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Dallmann H.G., McHenry C.S. & Marians K.J. (1996) Coupling of a replicative polymerase and helicase: a tau–DnaB interaction mediates rapid replication fork movement. Cell, 84, 643–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori H. et al. (1999) Crystal structure of a prokaryotic replication initiator protein bound to DNA at 2.6 Å resolution. EMBO J., 18, 4597–4607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konieczny I. & Marszalek J. (1995) The requirement for molecular chaperones in λ DNA replication is reduced by the mutation p in λP Gene, which weakens the interaction between λ P protein and DnaB helicase. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 9792–9799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konieczny I. & Helinski D.R. (1997) Helicase delivery and activation by DnaA and TrfA proteins during the initiation of replication of the broad host range plasmid RK2. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 33312–33318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konieczny I. & Zylicz M. (1999) in Genetic Engineering, Principles and Methods (ed. Setlow, J.K.) Vol. 21, 95–111. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konieczny I., Doran K.S., Helinski D.R. & Blasina A. (1997) Role of TrfA and DnaA proteins in origin opening during initiation of DNA replication of the broad host range plasmid RK2. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 20173–20178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornacki J.A., West A.H. & Firshein W. (1984) Proteins encoded by the trans-acting replication and maintenance regions of broad host range plasmid RK2. Plasmid, 11, 48–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuzer K.N. & Morrical S.W. (1994) in Molecular Biology of Bacteriophage T4. (ed. Karam, J.D.) 28–42. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Kruger R., Konieczny I. & Filutowicz M. (2001) Monomer/dimer ratios of replication protein modulate the DNA strand-opening in a replication origin. J. Mol. Biol., 306, 945–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanka E. & Schuster H. (1983) The dnaC protein of Escherichia coli. Purification, physical properties and interaction with dnaB protein. Nucleic Acids Res, 11, 987–997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Learn B.A., Um S.-J., Huang L. & McMacken R. (1997) Cryptic singlestranded-DNA binding activities of the phage lambda P and Escherichia coli DnaC replication initiation proteins facilitate the transfer of E. coli DnaB helicase onto DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 1154–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBowitz J.H. & McMacken R. (1986) The Escherichia coli dnaB replication protein is a DNA helicase. J. Biol. Chem., 261, 4738–4748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y.-B., Datta H.J. & Bastia D. (1998) Mechanistic studies of initiator–initiator interaction and replication initiation. EMBO J., 17, 5192–5200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y.-B., Ratnakar P.V.A.L., Mohanty B.K. & Bastia D. (1996) Direct physical interaction between DnaG primase and DnaB helicase of Escherichia coli is necessary for optimal synthesis of primer RNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 12902–12907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marszalek J. & Kaguni J.M. (1994) DnaA protein directs the binding of DnaB protein in initiation of DNA replication in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 4883–4890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messer W. et al. (2001) Bacterial replication initiator DnaA. Rules for DnaA binding and roles of DnaA in origin unwinding and helicase loading. Biochimie, 83, 5–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay G., Carr K.M., Kaguni J.M. & Chattoraj D.K. (1993) Open-complex formation by the host initiator, DnaA, at the origin of P1 plasmid replication. EMBO J, 12, 4547–4554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacek M., Konopa G. & Konieczny I. (2001) DnaA box sequences as the site for helicase delivery during plasmid RK2 replication initiation in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 23639–23644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park K., Mukhopadhyay S. & Chattoraj D.K. (1998) Requirements for and regulation of origin opening of plasmid P1. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 24906–24911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S.S. & Picha K.M. (2000) Structure and function of hexameric helicases. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 69, 651–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perri S., Helinski D.R. & Toukdarian A. (1991) Interactions of plasmid-encoded replication initiation proteins with the origin of DNA replication in the broad host range plasmid RK2. J. Biol. Chem., 266, 12536–12543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratnakar P.V., Mohanty B.K., Lobert M. & Bastia D. (1996) The replication initiator protein pi of the plasmid R6K specifically interacts with the host-encoded helicase DnaB. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 5522–5526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherzinger E., Haring V., Lurz R. & Otto S. (1991) Plasmid RSF1010 DNA replication in vitro promoted by purified RSF1010 RepA, RepB and RepC proteins. Nucleic Acid Res., 19, 1203–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherzinger E., Ziegelin G., Barcena M., Carazo J.M., Lurz R. and Lauka E. (1997) The RepA protein of plasmid RSF1010 is a replicative DNA helicase. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 30228–30236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidhauser T.J., Filutowicz M. & Helinski D.R. (1983) Replication of derivatives of the broad host range plasmid RK2 in two distantly related bacteria. Plasmid, 9, 325–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnos M., Zahn K., Inman R.B. & Blattner F.R. (1988) Initiation protein induced helix destabilization at the lambda origin: a prepriming step in DNA replication. Cell, 52, 385–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah D.S., Cross M.A., Porter D. & Thomas C.M. (1995) Dissection of the core and auxiliary sequences in the vegetative replication origin of promiscuous plasmid RK2. J. Mol. Biol., 254, 608–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma R., Kachroo A. & Bastia D. (2001) Mechanistic aspects of DnaA–RepA interaction as revealed by yeast forward and reverse two-hybrid analysis. EMBO J., 20, 4577–4587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shingler V. & Thomas C.M. (1984) Analysis of the trfA region of broad host-range plasmid RK2 by transposon mutagenesis and identification of polypeptide products. J. Mol. Biol., 175, 229–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speck C. & Messer W. (2001) Mechanism of origin unwinding: sequential binding of DnaA to double- and singlestranded DNA. EMBO J., 20, 1469–1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenzel T.T., Patel P. & Bastia D. (1991) Cooperativity at a distance promoted by the combined action of two replication initiator proteins and a DNA bending protein at the replication origin of pSC101. Genes Dev., 5, 1453–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tougu K. & Marians K.J. (1996) The extreme C terminus of primase is required for interaction with DnaB at the replication fork. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 21391–21397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickner S. & Hurwitz J. (1975) Interaction of Escherichia coli dnaB and dnaC gene products in vitro. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 72, 921–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X. et al. (2002) The Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum MCM protein can form heptameric rings. EMBO Rep., 3, 792–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]