Abstract

To allow DNA replication only once per cell cycle, origins of replication are reactivated ('licensed') during each G1 phase. Licensing is facilitated by assembly of the pre-replicative complex (pre-RC) at origins that concludes with loading the mini-chromosome maintenance (MCM) complex onto chromatin. Here we show that a virus exploits pre-RC assembly to selectively inhibit cellular DNA replication. Infection of quiescent primary fibroblasts with human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) induces all pre-RC factors. Although this is sufficient to assemble the MCM-loading factors onto chromatin, as it is in serum-stimulated cells, the virus inhibits loading of the MCM complex itself, thereby prematurely abrogating replication licensing. This provides a new level of control in pre-RC assembly and a mechanistic rationale for the unusual HCMV-induced G1 arrest that occurs despite the activation of the cyclin E-dependent transcription programme. Thus, this particularly large virus might thereby secure the supply with essential replication factors but omit competitive cellular DNA replication.

Introduction

In contrast to DNA tumour viruses that lead to an induction of S phase in infected cells, herpesviruses block cell cycle progression in G1 (Flemington, 2001). For human cytomegalovirus this cell cycle arrest is unusual (Kalejta & Shenk, 2002). When quiescent cells are infected with HCMV they enter the cell cycle even in the absence of additional growth factors leading to post-restriction-point characteristics including high cyclin E-associated kinase activity (Bresnahan et al., 1996; Wiebusch & Hagemeier, 2001), hyperphosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein (Rb) (Jault et al., 1995) and an induction of genes whose products are required for cell cycle progression and DNA replication (Song & Stinski, 2002). At the same time, however, infected cells are locked with a G1 DNA content (Bresnahan et al., 1996; Dittmer & Mocarski, 1997; Wiebusch & Hagemeier, 2001) and serum addition cannot rescue DNA replication in these cells (Lu & Shenk, 1996; Wiebusch & Hagemeier, 2001), indicating that HCMV interferes directly with cellular DNA synthesis. The notion that partly replicated genomes are not observed when proliferating primary fibroblasts are infected (Lu & Shenk, 1996; L.W. and C.H., unpublished observations) focused our interest on a possible impact of HCMV on the initial steps of DNA replication, namely the assembly of the pre-RC.

The pre-RC is a highly conserved multi-protein complex consisting of factors of the origin recognition complex (ORC1–6), the MCM-loading factors CDC6 and CDT1 and the MCM complex (MCM2–7) (Bell & Dutta, 2002). Its stepwise assembly onto chromatin is the molecular basis for the process of replication licensing in G1 that is a prerequisite for the initiation of DNA synthesis at origins of replication in S phase. Pre-RC disassembly after MCM loading ensures that each part of the genome is only replicated once per cell cycle (Blow & Laskey, 1988; Diffley et al., 1994, Blow & Hodgson, 2002). In non-cycling, quiescent cells the pre-RC cannot be assembled owing to the absence of MCM, CDC6 and ORC1 gene expression. When cells are induced to re-enter the cell cycle from quiescence (G0), transcription of those factors becomes activated in an E2F-dependent manner (Ohtani et al., 1996; Leone et al., 1998) and, in addition, CDC6 protein stability increases owing to inactivation of the anaphase-promoting complex (APC) (Petersen et al., 2000). The assembly of the pre-RC during G0/S-transition has recently been demonstrated to be positively regulated by cyclin E (Cook et al., 2002; Coverley et al., 2002).

We have started our analysis of a possible direct impact of HCMV on cellular DNA replication by addressing the question of whether the virus can target the process of replication licensing. Here we show that HCMV prevents pre-RC assembly by inhibiting MCM loading onto chromatin.

Results and Discussion

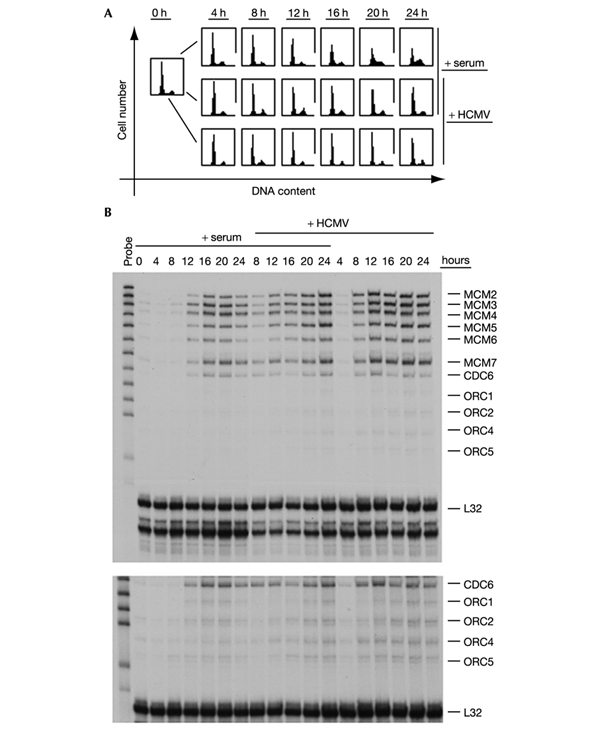

Because most of the genes encoding pre-RC factors are not transcribed in G0 (Ohtani et al., 1996; Leone et al., 1998), we first examined whether deregulated expression of this complex set of genes could be the reason for the lack of DNA replication in hCMV-infected cells. We prepared RNA from primary embryonic lung fibroblasts that after serum deprivation were either (1) treated again with serum or (2) infected with HCMV with or without added serum. Under these conditions control cells restimulated with serum, but not virus-infected cells, had replicated their DNA and had entered G2 after 24 h (Fig. 1A). Figure 1B shows a multi-probe RNase protection assay (RPA) in which pre-RC messenger RNAs including ORC1, ORC2, ORC4, ORC5, CDC6 and MCM2–7 were analysed in parallel. HCMV was sufficient to induce the expression of all genes tested, albeit with slightly earlier kinetics than in serumstimulated cells. The overall similarity of the expression patterns in infected and serum-treated cells was surprising and supports the view that the virus is likely to switch on, in a general manner, key regulatory pathways that are also activated after growth factor treatment.

Figure 1.

HCMV induces a transcription programme activating pre-RC gene expression in quiescent cells. Subconfluent, human embryonic lung fibroblasts were sent into quiescence by a 3-d period of growth factor deprivation. Then (0 h) cells were either re-stimulated with serum (+ serum), infected with HCMV (+ HCMV), or both. At the indicated time points, cells were harvested and processed for downstream applications. (A) Cell-cycle profiles were obtained by flow cytometry analysis of cellular DNA content. (B) Levels of MCM, CDC6 and ORC mRNAs were determined by multi-probe RPA, with the ribosomal gene L32 as a loading control. The lower panel shows a longer exposure of the same gel to improve the detectioin of the weaker signals deriving from ORC mRNAs.

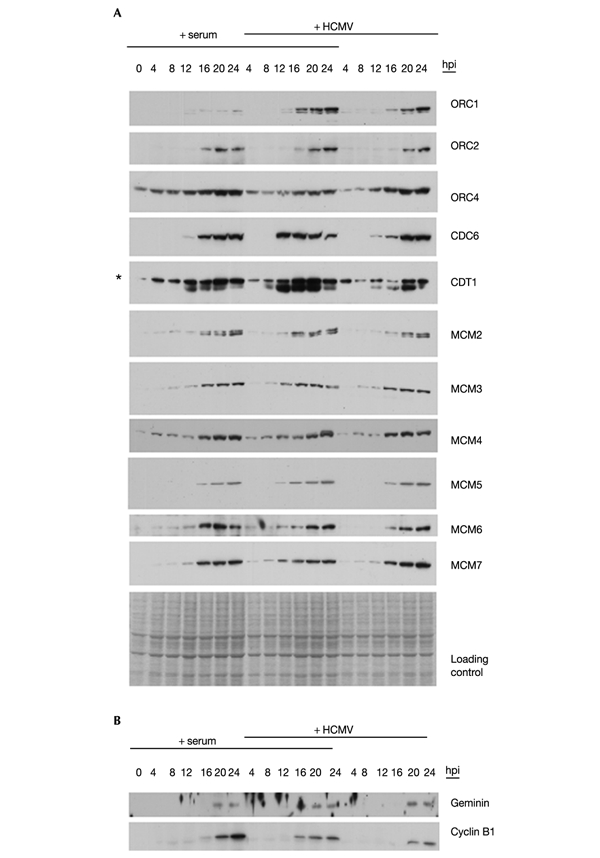

The ability of HCMV to induce pre-RC gene transcription led us next to investigate the encoded proteins including CDT1, an essential MCM-loading factor (Maiorano et al., 2000). Whole cell extracts used for immunoblotting were derived from aliquots of the previous experiment. The overall picture of this analysis again shows a remarkable similarity of protein expression patterns in serum-treated versus infected cells (Fig. 2A). Both the expression levels and the kinetics of MCM2–7, ORC2, ORC4 and CDC6 proteins were nearly identical in the three subgroups. ORC1 was significantly upregulated in infected cells, which seems to be due to both transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms (Fig. 1B; Shirakata et al., 2002). We also observed a marked upregulation of CDT1 protein when infected cells were also stimulated with serum. However, the virally mediated G1 arrest could not be readily explained by the differences in expression of pre-RC factors.

Figure 2.

Pre-RC proteins become fully expressed in HCMV-infected fibroblasts. After synchronization in G0, fibroblasts were stimulated with serum (+ serum) and/or infected (+ HCMV) as described for Fig. 1. Expression kinetics of the indicated pre-RC proteins (A) or APC targets (B) were monitored at the protein level by immunoblotting whole cell extracts taken at 4 h intervals as indicated. Equal loading was based on cell number and controlled for by staining with Coomassie blue. Nonspecific bands are marked with an asterisk. hpi, hours post-infection.

CDT1 is negatively regulated at a post-translational level by geminin (Wohlschlegel et al., 2000; Tada et al., 2001) which itself is a direct proteolytic substrate of the APC (McGarry & Kirschner, 1998). Surprisingly, we could detect geminin protein in infected G1-arrested cells, although in cells restimulated with serum it is not detectable before the onset of DNA replication (Fig. 2B; Nishitani et al., 2001). The finding that the appearance of cyclin B1, which underlies the same APC-dependent proteolytic pathway (McGarry & Kirschner, 1998), was identical with that of geminin implies that the APC becomes inactivated in cells infected by HCMV (Fig. 2B). However, it seems unlikely that the presence of geminin has any consequence for pre-RC assembly in infected cells, because it is stabilized not before 20 h after infection, at times when serum-treated cells have clearly entered S phase.

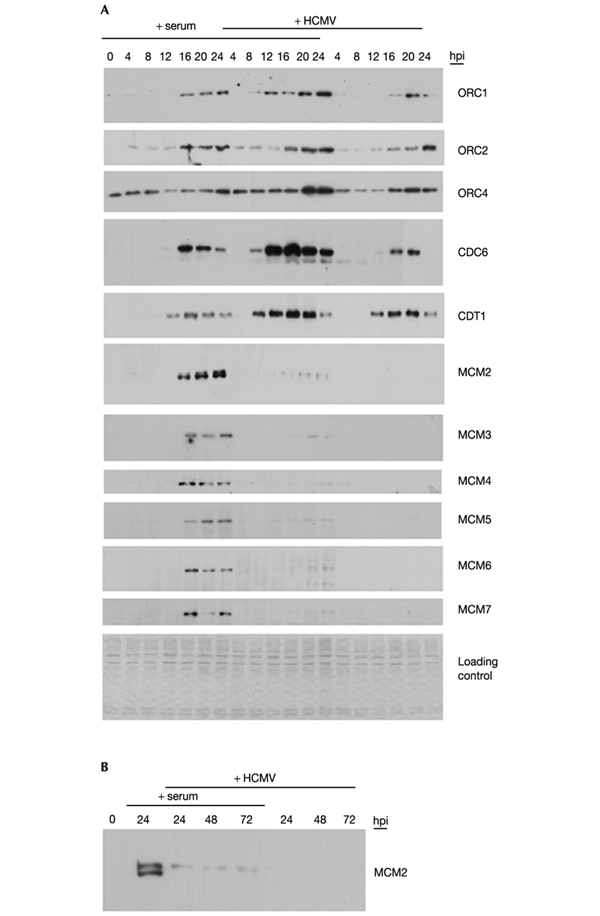

The above data show that in HCMV-infected cells all pre-RC factors are available for assembly to load the MCM complex onto chromatin at origins of replication and hence to license them for DNA replication (ORC3, ORC5 and ORC6 could not be analysed faithfully owing to the unavailability of appropriate antibodies). To test replication licensing directly in infected cells, we prepared a micrococcal-nuclease-sensitive chromatin fraction from aliquots of fibroblasts shown in Fig. 1A and analysed by immunoblotting for the presence of pre-RC factors (Fig. 3A). In G0 cells, only ORC4 was associated with chromatin. After release from growth arrest in non-infected cells, first ORC2 and then Cdt1 were recruited, the latter even before ORC1. Instead, ORC1 seems to associate with chromatin in the same time window as CDC6, also coinciding with recruitment of the MCM hexameric complex. Although MCMs like ORCs remained bound to chromatin during S-phase progression, the MCM-loading factors CDC6 and CDT1 rapidly dissociated from chromatin after MCM recruitment had begun.

Figure 3.

MCM loading onto chromatin is inhibited by HCMV. Serum-starved fibroblasts were stimulated with serum (+ serum) and/or infected (+ HCMV) as described for Fig. 1. Up to 24 h after infection, cells were collected every 4 h (A) and over the following days at intervals of 24 h (B). Chromatin fractions were then prepared and subjected to immunoblot analysis with the same antibodies as for the detection of soluble proteins. Again, the extracts were adjusted to equal cell numbers and loading was controlled for by staining with Coomassie blue. hpi, hours post-infection.

In infected cells the strong upregulation of soluble ORC1 (Fig. 2A) did not translate into an increased association with chromatin. Similarly, the late increase of geminin in infected cells (Fig. 2B) had, as expected, no negative impact on CDT1 recruitment into the pre-RC, which seemed properly assembled up to this stage. However, in sharp contrast, HCMV strongly inhibited MCM loading onto chromatin, showing that pre-RC licensing of origins is abrogated in infected cells. This effect cannot be explained by the slight differences in the kinetics of chromatin association of ORC and MCM-loading factors because between 16 and 20 h, when those proteins are bound to chromatin both in the presence and in the absence of HCMV, there is still no MCM loading in infected cells.

Not only was the loss of MCM loading delayed, but the loss was maintained throughout the infectious cycle of 72 h as examplified by MCM2 analysis (Fig. 3B). In addition, the MCMs remained nuclear in infected cells (data not shown). Interestingly, the small amount of chromatin-associated MCM2 that was detectable in infected and serum-treated cells reflects the unphosphorylated and hence non-activated form of the protein (Lei et al., 1997; Jiang et al., 1999) which in this particular case the slower-migrating species resembles (Todorov et al., 1995; Fujita et al., 1998; Masai et al., 2000). This suggests that the virus can also negatively affect MCM activation (Lei & Tye, 2001).

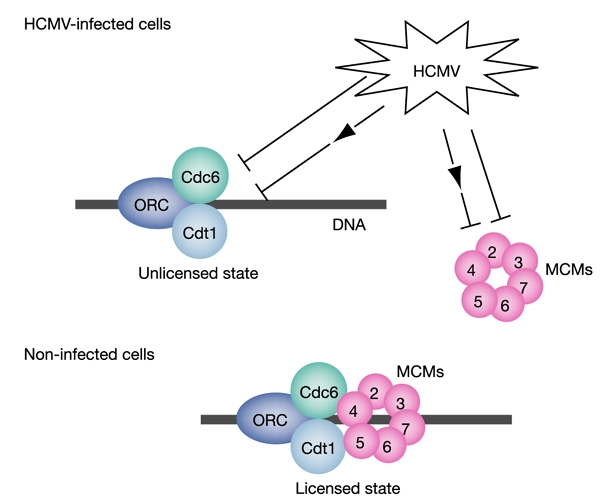

Our finding of an absence of MCM loading despite a fully assembled MCM-loading complex is unprecedented. Cyclin E–cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (Cdk2), which positively influences pre-RC assembly (Cook et al., 2002; Coverley et al., 2002) is upregulated and Cyclin A–Cdk2, a negative regulator (Blow & Hodgson, 2002; Coverley et al., 2002), is downregulated in HCMV-infected cells (Jault et al., 1995; Bresnahan et al., 1996), indicating a CDK-independent mechanism of pre-RC inhibition during infection. Our data are most consistent with a model in which HCMV targets either MCMs or their loading factors CDC6/CDT1 more directly (Fig. 4). For instance, HCMV might interfere with the ATPase function of CDC6 that is essential for MCM but not CDC6 chromatin association (Takahashi et al., 2002). Alternatively, the virus could possibly also target MCMs directly, to subvert the complex to viral origins (Chaudhuri et al., 2001).

Figure 4.

The pre-RC targeting model of HCMV-mediated cell-cycle arrest. HCMV prevents MCM loading onto chromatin, resulting in incomplete pre-RC assembly (ORC, CDC6 and CDT1) and an unlicensed state of replication origins. The model suggests that HCMV targets the MCM-loading factors (CDC6 and/or CDT1) or the MCM complex itself either directly (⊣) or indirectly via as yet unidentified cellular intermediates (⊣→).

Furthermore, our data provide an explanation for the unusual HCMV-mediated cell cycle arrest. Cellular DNA replication is specifically omitted by inhibiting replication licensing, but Cdk-dependent cell cycle progression is, it seems, allowed to proceed so that competitive cellular DNA synthesis is dissociated from the essential supply of replication factors. Which viral factors might be responsible for such a dissociation? Currently, there are two promising candidates, pUL69 and IE2/IE86: both proteins are present in the cell immediately after infection and have the capacity to stop cell proliferation autonomously (Lu & Shenk, 1999; Wiebusch & Hagemeier, 1999). The pUL69-mediated G1 arrest is largely uncharacterized but seems to be important for full expression of the cell cycle arrest by HCMV (Hayashi et al., 2000). The IE2-mediated arrest is characterized by a block in DNA replication that is independent of Cdk; this block coexists with a derepressed Rb–E2F pathway and occurs in early S phase in transformed cell lines (Murphy et al., 2000; Wiebusch & Hagemeier, 2001). The latter does not necessarily exclude a putative anti-licensing action of IE2 because transformed (in contrast to primary) cells have recently been shown to be able to respond to licensing inhibition by an arrest at S phase rather than at G1 (Shreeram et al., 2002).

Our work provides the basis for a definition of the HCMV licensing inhibitor(s), and future work aims at analysing a possible involvement of the aforementioned candidates. Moreover, defining the exact interface of this interaction between virus and host cell could open up new opportunities for the development of anti-viral drugs as well as potentially yielding new anti-proliferative strategies.

Methods

Cells and infections.

Human embryonic lung fibroblasts (passage numbers 13–20) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). For growth-factor deprivation, FCS was omitted from the culture medium. For re-stimulation this medium was replaced with fresh medium containing 20% FCS. Infections were performed by incubating cells for 1 h with an appropriate volume of serum-free medium containing virus. The hCMV laboratory strain AD169 was used at a multiplicity of infection of 10. Whole cell extracts were prepared by sonicating cells in Laemmli buffer. Cellular chromatin was isolated exactly as described (Mendez and Stillman, 2000).

Flow cytometry and multi-probe RPA.

For flow-cytometric analysis of DNA content, cells were permeabilized in 75% ethanol, treated with RNase and stained with propidium iodide as described (Wiebusch & Hagemeier, 2001). Multi-probe RPA was performed as described (Wiebusch & Hagemeier, 2001) with the hORC template set (BD Pharmingen).

Antibodies and immunoblotting.

The ORC1 antibody was a gift from J. Mendez and B. Stillman (Cold Spring Harbor, New York, USA). The antibodies used for the detection of ORC2, ORC4, MCM2, MCM5, MCM6 (all from BD Transduction Laboratory), ORC5, MCM3, MCM4 (all from BD Pharmingen), MCM7 (clone DCS-141, Neomarkers), CDC6 and cyclin B1 (clones 180.2 and GNS1, respectively, from Santa Cruz Biotechnology) are commercially available. The CDT1 antibody was kindly provided by H. Nishitani (Fukuoka, Japan). Geminin was detected with an antibody raised against Xenopus geminin that crossreacted with the human homologue (obtained from J. Blow, Dundee, UK). Immunoblotting was performed essentially as described by Wiebusch & Hagemeier (2001). To reach the high sensitivity required for the detection of chromatin-associated pre-RC proteins in primary fibroblasts, blots were incubated in the primary antibody solution for 16–40 h at 4 °C and developed with the chemiluminescence reagents ECL-plus (Amersham) or Supersignal-West-Femto (Pierce), depending on signal strength.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) to C.H.

References

- Bell S.P. & Dutta A. (2002) DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 71, 333–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blow J.J. & Laskey R.A. (1988) A role for the nuclear envelope in controlling DNA replication within the cell cycle. Nature, 332, 546–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blow J.J. & Hodgson B. (2002) Replication licensing—defining the proliferative state? Trends Cell Biol., 12, 72–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresnahan W.A., Boldogh I., Thompson E.A. & Albrecht T. (1996) Human cytomegalovirus inhibits cellular DNA synthesis and arrests productively infected cells in late G1. Virology, 224, 150–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri B., Xu H., Todorov I., Dutta A. & Yates J.L. (2001) Human DNA replication initiation factors, ORC and MCM, associate with oriP of Epstein–Barr virus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 10085–10089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook J.G. et al. (2002) Analysis of Cdc6 function in the assembly of mammalian prereplication complexes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 1347–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coverley D., Laman H. & Laskey R.A. (2002) Distinct roles for cyclins E and A during DNA replication complex assembly and activation. Nature Cell Biol., 4, 523–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diffley J.F., Cocker J.H., Dowell S.J. & Rowley A. (1994) Two steps in the assembly of complexes at yeast replication origins in vivo. Cell, 78, 303–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmer D. & Mocarski E.S. (1997) Human cytomegalovirus infection inhibits G1/S transition. J. Virol., 71, 1629–1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flemington E.K. (2001) Herpesvirus lytic replication and the cell cycle: arresting new developments. J. Virol., 75, 4475–4481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita M. et al. (1998) Cell cycle- and chromatin binding state-dependent phosphorylation of human MCM heterohexameric complexes. A role for cdc2 kinase. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 17095–17101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi M.L., Blankenship C. & Shenk T. (2000) Human cytomegalovirus UL69 protein is required for efficient accumulation of infected cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 2692–2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jault F.M. et al. (1995) Cytomegalovirus infection induces high levels of cyclins, phosphorylated Rb, and p53, leading to cell cycle arrest. J. Virol., 69, 6697–6704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W., McDonald D., Hope T.J. & Hunter T. (1999) Mammalian Cdc7-Dbf4 protein kinase complex is essential for initiation of DNA replication. EMBO J., 18, 5703–5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalejta R.F. & Shenk T. (2002) Manipulation of the cell cycle by human cytomegalovirus. Front. Biosci., 7, D295–D306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei M. et al. (1997) Mcm2 is a target of regulation by Cdc7-Dbf4 during the initiation of DNA synthesis. Genes Dev., 11, 3365–3374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei M. & Tye B.K. (2001) Initiating DNA synthesis: from recruiting to activating the MCM complex. J. Cell Sci., 114, 1447–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone G. et al. (1998) E2F3 activity is regulated during the cell cycle and is required for the induction of S phase. Genes Dev., 12, 2120–2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M. & Shenk T. (1996) Human cytomegalovirus infection inhibits cell cycle progression at multiple points, including the transition from G1 to S. J. Virol., 70, 8850–8857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M. & Shenk T. (1999) Human cytomegalovirus UL69 protein induces cells to accumulate in G1 phase of the cell cycle. J. Virol., 73, 676–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiorano D., Moreau J. & Mechali M. (2000) XCDT1 is required for the assembly of pre-replicative complexes in Xenopus laevis. Nature, 404, 622–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masai H. et al. (2000) Human Cdc7-related kinase complex. In vitro phosphorylation of MCM by concerted actions of Cdks and Cdc7 and that of a criticial threonine residue of Cdc7 by Cdks. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 29042–29052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarry T.J. & Kirschner M.W. (1998) Geminin, an inhibitor of DNA replication, is degraded during mitosis. Cell, 93, 1043–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez J. & Stillman B. (2000) Chromatin association of human origin recognition complex, cdc6, and minichromosome maintenance proteins during the cell cycle: assembly of prereplication complexes in late mitosis. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 8602–8612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E.A., Streblow D.N., Nelson J.A. & Stinski M.F. (2000) The human cytomegalovirus IE86 protein can block cell cycle progression after inducing transition into the S phase of permissive cells. J. Virol., 74, 7108–7118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishitani H., Taraviras S., Lygerou Z. & Nishimoto T. (2001) The human licensing factor for DNA replication Cdt1 accumulates in G1 and is destabilized after initiation of S-phase. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 44905–44911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtani K., DeGregori J., Leone G., Herendeen D.R., Kelly T.J. & Nevins J.R. (1996) Expression of the HsOrc1 gene, a human ORC1 homolog, is regulated by cell proliferation via the E2F transcription factor. Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 6977–6984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen B.O. et al. (2000) Cell cycle- and cell growth-regulated proteolysis of mammalian CDC6 is dependent on APC-CDH1. Genes Dev., 14, 2330–2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirakata M. et al. (2002) Novel immediate-early protein IE19 of human cytomegalovirus activates the origin recognition complex I promoter in a cooperative manner with IE72. J. Virol., 76, 3158–3167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shreeram S., Sparks A., Lane D.P. & Blow J.J. (2002) Cell typespecific responses of human cells to inhibition of replication licensing. Oncogene, 21, 6624–6632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y.J. & Stinski M.F. (2002) Effect of the human cytomegalovirus IE86 protein on expression of E2F-responsive genes: A DNA microarray analysis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 2836–2841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada S., Li A., Maiorano D., Mechali M. & Blow J.J. (2001) Repression of origin assembly in metaphase depends on inhibition of RLF-B/Cdt1 by geminin. Nature Cell Biol., 3, 107–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N., Tsutsumi S., Tsuchiya T., Stillman B. & Mizushima T. (2002) Functions of sensor 1 and sensor 2 regions of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cdc6p in vivo and in vitro. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 16033–16040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorov I.T., Attaran A. & Kearsey S.E. (1995) BM28, a human member of the MCM2-3-5 family, is displaced from chromatin during DNA replication. J. Cell Biol., 129, 1433–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiebusch L. & Hagemeier C. (1999) Human cytomegalovirus 86-kilodalton IE2 protein blocks cell cycle progression in G1. J. Virol., 73, 9274–9283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiebusch L. & Hagemeier C. (2001) The human cytomegalovirus immediate early 2 protein dissociates cellular DNA synthesis from cyclin-dependent kinase activation. EMBO J., 20, 1086–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlschlegel J.A. et al. (2000) Inhibition of eukaryotic DNA replication by geminin binding to Cdt1. Science, 290, 2309–2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]