Abstract

RNA polyadenylation occurs not only in eukaryotes but also in bacteria. In prokaryotes, polyadenylated RNA molecules are usually degraded more efficiently than non-modified transcripts. Here we demonstrate that two transcripts, which were shown previously to be substrates for poly(A) polymerase I (PAP I), Escherichia coli lpp messenger RNA and bacteriophage λ oop RNA, are polyadenylated more efficiently in slowly growing bacteria than in rapidly growing bacteria. Intracellular levels of PAP I varied in inverse proportion to bacterial growth rate. Moreover, transcription from a promoter for the pcnB gene (encoding PAP I) was shown to be more efficient under conditions of low bacterial growth rates. We conclude that efficiency of RNA polyadenylation in E. coli is higher in slowly growing bacteria because of more efficient expression of the pcnB gene. This may allow regulation of the stability of certain transcripts (those subjected to PAP I-dependent polyadenylation) in response to various growth conditions.

Introduction

Despite the fact that bacterial poly(A) polymerase was described 40 years ago (August et al., 1962), specific polyadenylation at the 3′ end of RNA was for a long time believed to be unique to eukaryotic messenger RNAs. Studies of the last ten years, initiated by the discovery of the structural gene for poly(A) polymerase I (PAP I) in Escherichia coli (Cao & Sarkar, 1992a), clearly demonstrated that prokaryotic RNAs are also polyadenylated.

Two poly(A) polymerases, PAP I and PAP II, were discovered in E. coli. PAP I, which is responsible for over 90% of poly(A) polymerase activity in E. coli cells (O'Hara et al., 1995; Mohanty & Kushner, 1999a), is encoded by the pcnB gene (Cao & Sarkar, 1992a), but the gene encoding PAP II is still unknown (Mohanty & Kushner, 1999b). One could speculate that polynucleotide phosphorylase (PNPase) functions as an exonuclease and also as a poly(A) polymerase, which could account for the activity of PAP II. Various RNA molecules are polyadenylated with different efficiency, and it appears that the susceptibility of certain RNAs to polyadenylation depends on the presence of singlestranded segments at either the 5′ or the 3′ end and monophosphorylation at an unpaired 5′ terminus (Feng & Cohen, 2000; Yehudai-Resheff & Schuster, 2000).

There are many reports indicating that bacterial RNA polyadenylation leads to decreased stability of transcripts (O'Hara et al., 1995; Xu & Cohen, 1995; Szalewska-Pałasz et al., 1998; Blum et al., 1999). Results of other experiments showed either stabilization of specific transcripts, or a lack of effect on the half-lives of other mRNAs after enhanced polyadenylation (Mohanty & Kushner, 1999a). However, transcripts stabilized or unaffected by polyadenylation are very rare, and it is therefore generally accepted that this process may regulate gene expression by promoting RNA degradation (for reviews see Sarkar, 1996; Carpousis et al., 1999; Rauhut & Klug, 1999; Regnier & Arraiano, 2000; Steege, 2000).

If RNA polyadenylation plays a regulatory role in gene expression, it follows that the activity or level of poly(A) polymerase in cells should be modulated under certain physiological conditions, such that stability of various RNAs could be regulated in response to environmental factors. However, although there has been remarkable progress in understanding the biochemical properties and functions of PAP I, the biological significance of bacterial RNA polyadenylation, and that of the resultant enhanced transcript degradation, remains unclear. We therefore investigated the efficiency of RNA polyadenylation in E. coli under different growth conditions. We employed lpp mRNA and bacteriophage λ oop RNA as model transcripts. Both transcripts were previously demonstrated to be specifically polyadenylated by PAP I (Cao & Sarkar, 1992b; O'Hara et al., 1995; Wróbel et al., 1998; Mohanty & Kushner, 1999a), and polyadenylation of lpp and oop RNAs leads to a significant decrease in their stability in E. coli cells (O'Hara et al., 1995; Szalewska-Pałasz et al., 1998; Mohanty & Kushner, 1999a).

Results

Increased RNA polyadenylation in slowly growing cells

To investigate the efficiency of RNA polyadenylation in E. coli cells cultured at different growth rates, we used various culture media. This method was previously proved to be adequate for achieving different generation times of the same strain with relatively minor effects on other physiological parameters (Nilsson et al., 1984; Hadas et al., 1977; Gabig et al., 1998; Wȩgrzyn et al., 2000). Growth rates of the E. coli strains in different media were determined (Table 1).

Table 1.

Generation times of E. coli strains growing in different media at 37 °C and copy numbers of plasmid pBR322 in the MG1655 strain under these conditions

| Medium | Generation time (min) | Plasmid copy numbera | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MG1655/pKB2 | VH1000:: ppcnB-lacZ | MG1655/pKB2 | |

| LB | 34 | 28 | 15 ± 3 |

| MMGlu | 76 | 50 | 29 ± 5 |

| MMGly | 119 | 77 | 42 ± 5 |

| MMSuc | 140 | 86 | 60 ± 6 |

| MMAce | 216 | 134 | 76 ± 8 |

a Results from three experiments are shown, as means ± s.d.

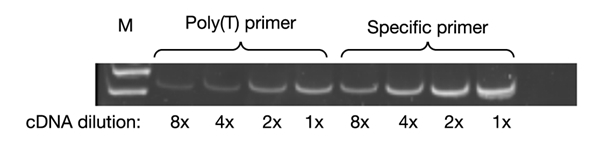

The percentage of polyadenylated lpp and oop transcripts was determined using the kinetic polymerase chain reaction with reverse transcription (RT–PCR) method described previously (Ferre et al., 1996; Mohanty & Kushner, 1999a). Using this method, we were able to estimate amounts of polyadenylated RNA and total RNA (which included both polyadenylated and non-polyadenylated RNAs) for each transcript. We demonstrated that putative annealing of the oligo-dT primer to internal stretches of A residues does not impair the analysis, and that RT–PCR amplification is proportional to the amount of polyadenylated RNA (Fig. 1). When the reactions were repeated using RNA isolated from a pcnB mutant, very little polyadenylation of lpp and oop transcripts was observed (data not shown). When different amounts of RNA isolated from pcnB+ cells were adjusted to identical amounts of total RNA with RNA isolated from pcnB mutant cells, the expected percentage of polyadenylated transcripts was always very similar (less than 5% difference assuming the expected value to be 100%) to the value estimated on the basis of the RT–PCR procedure (data not shown).

Figure 1.

An example of RT–PCR experiments. The lpp transcript was detected by RT–PCR in samples of RNA isolated from bacteria growing in the MMGly medium. Different dilutions of cDNA were used, as indicated. The specific primer (REVLPP) was diluted to a concentration of one-half that of the poly(T) primer. Lane M contains molecular weight markers.

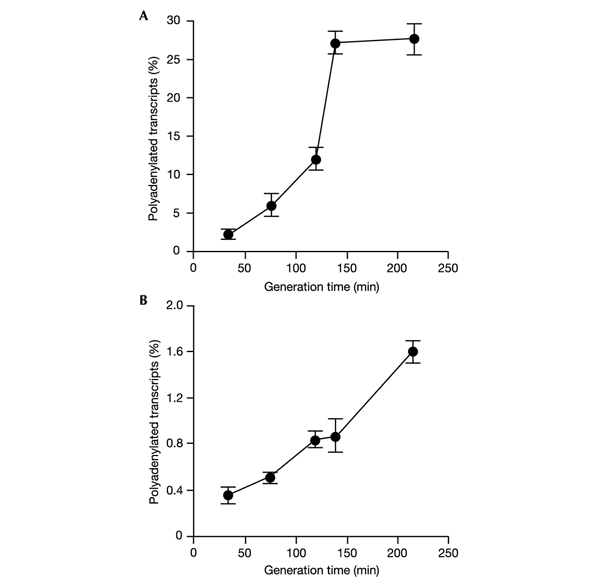

We found that efficiency of polyadenylation of the lpp transcript depends on bacterial growth rate: the slower the cell growth, the higher the percentage of polyadenylated lpp mRNA observed (Fig. 2A). A very similar result was observed for oop RNA, transcribed from a bacteriophage λ-derived plasmid (Fig. 2B), despite considerable differences between these two transcripts in the general efficiency of their polyadenylation.

Figure 2.

Efficiency of polyadenylation of lpp and oop transcripts in E. coli MG1655/pKB2 strain at different bacterial growth rates, as estimated by the kinetic RT–PCR method. The percentage of polyadenylated lpp (A) and oop (B) transcripts are shown. Average values from three experiments are shown, with error bars ± s.d.

Level of PAP at various bacterial growth rates

It has been demonstrated that overexpression of the pcnB gene, encoding PAP I, results in a significant increase in the percentage of polyadenylated transcripts (Mohanty & Kushner, 1999a). We therefore investigated whether increased efficiency of polyadenylation observed in slowly growing bacteria arises from higher PAP I levels under these conditions.

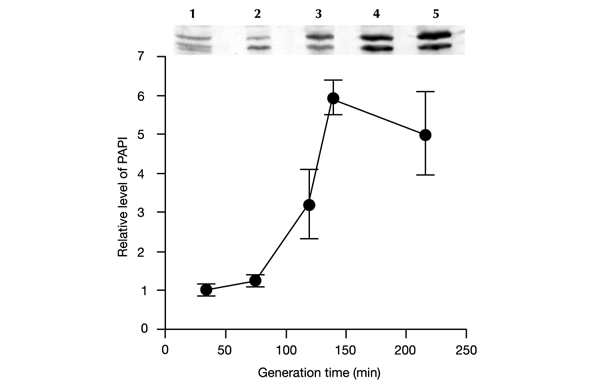

A hexahistidine (His6)-tagged truncated form of PAP I was overexpressed, purified and used for the production of a rabbit anti-PAP I serum. The specificity of this serum was proven, as no signal was detected when cell lysates from ΔpcnB::kan mutants were analysed by performing western blots, whereas PAP I bands were easily detectable in similar samples from wild-type bacteria (Fig. 3). The intensity of the signal was found to be proportional to the amount of PAP I (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Relative amounts of PAP I in E. coli MG1655/pKB2 strain at different bacterial growth rates, as estimated by western blotting. A western blot is shown above the graph (lanes, labelled 1 to 5, correspond to consecutive points on the graph). PAP I migrates on denaturing PAGE as a doublet band (see Cao & Sarkar, 1992a). Average values from three experiments are shown, with error bars ± s.d.

We found that levels of PAP I are significantly higher in slowly growing cells than in bacteria cultivated in media supporting high growth rates (Fig. 3). These results suggest a correlation between levels of PAP I in E. coli cells and the percentage of polyadenylated lpp and oop transcripts.

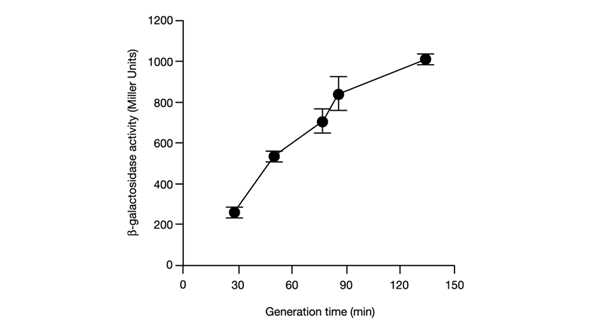

Growth-rate-dependent activity of the pcnB gene promoter

The region of the pcnB promoter was cloned into a specific vector to construct a multicopy fusion of this promoter with the lacZ reporter gene. A strain bearing a single copy of this fusion was then constructed by transferring the fusion into a bacteriophage λ-derived vector and subsequent lysogenization of the lacZ mutant host. The activity of this fusion construct was measured in bacteria growing in various media, and it was found that the pcnB promoter is more active in slowly growing cells than in media supporting higher growth rates of E. coli (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Activity of β-galactosidase in an E. coli VH1000 host bearing a ppcnB-lacZ fusion at different cell growth rates. Average values from three experiments are shown, with error bars ± s.d.

Degradation of RNA at different bacterial growth rates

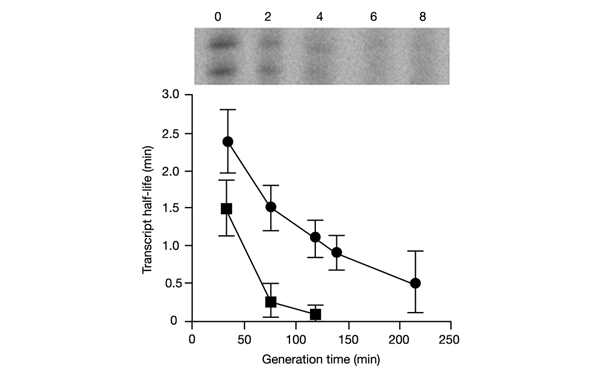

In previous studies, no significant effect of bacterial growth rate on degradation of lpp mRNA ws observed (Nillson et al., 1984). This is in contrast to our demonstration of enhanced RNA polyadenylation in slowly growing cells. We therefore measured the stability of oop RNA and another transcript polyadenylated by PAP I, RNA I of a ColE1-like plasmid, pBR322, in bacteria growing in different media. We found that degradation of both oop RNA and RNA I is more efficient at low bacterial growth rates (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Degradation of RNA I and oop RNAs in E. coli MG1655/pBR322 and MG1655/pKB2 strains at different bacterial growth rates. Half-lives for RNA I (circles) and oop (squares) transcripts are indicated. Average values from three experiments are shown, with error bars ± s.d. A representative autoradiograph (samples isolated from bacteria growing in the MMGlu medium and tested for RNA I) is shown above the graph (numbers represent minutes after addition of rifampicin).

pBR322 plasmid copy number at different host growth rates

RNA I is an antisense transcript which negatively controls replication of ColE1-like plasmids. We therefore measured the copy number of pBR322 in bacteria growing in different media and found that the plasmid is present at higher copy numbers in slowly growing cells (Table 1). These results are compatible with the finding that the degradation of RNA I is dependent on growth rate (Fig. 5), although recent studies indicate that polyadenylation of RNA I may also decrease the interaction of this antisense transcript with the RNA II pre-primer (Xu et al., 2002).

Discussion

Polyadenylation of transcripts in bacteria is believed to be involved in the regulation of gene expression by influencing the efficiency of RNA degradation. However, any biological process can have a regulatory significance only if its efficiency depends on physiological conditions. Despite remarkable progress in understanding functions of the main E. coli poly(A) polymerase, PAP I, physiological factors controlling the efficiency of RNA polyadenylation have previously been unknown. However, it has been demonstrated that low levels of polyadenylation (at most a small percentage of polyadenylated RNA molecules), observed in E. coli strains growing in a rich medium, can be increased significantly by overexpression of the pcnB gene (Mohanty & Kushner, 1999a). It therefore appears that the level of PAP I in bacterial cells may be a limiting factor for RNA polyadenylation efficiency. If this is true, physiological conditions that cause enhanced expression of the pcnB gene should result in more efficient polyadenylation of certain transcripts, possibly influencing their degradation. Such regulation might be an important element of cellular responses to changing environmental conditions.

Here we demonstrate that polyadenylation of two transcripts, lpp and oop, is significantly increased in slowly growing cells. Both the activity of the pcnB gene promoter and the level of PAP I varied in inverse proportion to bacterial growth rate. Results of our preliminary experiments, in which we tried to detect modified transcripts directly on electrophoretic gels rather than after RT–PCR (see Szalewska-Pałasz et al. (1998) for technical details), suggest that the proportion of polyadenylated RNAs, but not lengths of poly(A) tails, vary in bacterial cells growing with different generation times (data not shown). One might argue that this is in contrast to previous reports, which concluded that both the proportion of polyadenylated RNA molecules and the length of poly(A) tails are increased in cells overexpressing PAP I (Mohanty & Kushner, 1999a, 2000). However, these studies used strains highly overexpressing a modified pcnB gene from a plasmid, whereas in our experiments the wild-type pcnB gene was expressed from a bacterial chromosome. Moreover, the plasmid-mediated pcnB overexpression was toxic to bacteria and caused cell death (Mohanty & Kushner 1999a, 2000), whereas bacteria were still growing in all the media used in the experiments described in this report. This indicates that the physiological conditions in both these sets of experiments could be significantly different.

Recent studies have suggested that expression of the pcnB gene is regulated at the level of translation (Binns and Masters, 2002). These studies have shown that translation of pcnB mRNA is initiated from an unusual and inefficient start codon (AUU), which is subject to a negative regulation such that most initiation events are aborted. In this report we demonstrate that expression from the pcnB promoter is dependent on growth rate. It therefore appears that expression of the pcnB gene is precisely regulated at various levels. Such precise regulation usually corresponds to a physiological importance of achieving optimal levels of a gene product under particular environmental conditions. Our results indicate that bacteria may adapt the expression levels of certain genes to various growth conditions by changing the levels of polyadenylation of transcripts, and thus by controlling the rates of their degradation. Because poly(A) polymerases act more readily on some transcripts than on others, (Mohanty & Kushner, 1999a; Feng & Cohen, 2000), polyadenylation may significantly influence transcriptomes of bacteria growing under conditions supporting different growth rates.

Growth-rate-dependent regulation of mRNA stability in E. coli was demonstrated almost two decades ago by Nilsson et al. (1984). In fact, in those studies, some transcripts were found to be less stable in slowly growing cells. One might speculate that this is at least partially due to changes in efficiency of RNA polyadenylation. Although the role of polyadenylation in the decay of full-length transcripts was considered controversial (Coburn & Mackie, 1999) and despite the fact that in a previous study no significant effect of bacterial growth rate on degradation of lpp mRNA was observed (Nilsson et al., 1984), we have demonstrated that degradation of RNA I and oop RNAs depends on bacterial growth rate. The reason for this discrepancy remains to be discovered. One possible explanation is that expression of genes encoding particular RNases may be dependent on growth rate. Moreover, the correlation between levels of polyadenylation and the rate of RNA degradation is not necessarily as straightforward under different cellular growth conditions as in the case of studies performed without changing culture media.

Methods

Bacterial strains.

All experiments were performed in the E. coli MG1655 (pyrE) strain (Jensen, 1993) and its pyrE+ lacI lacZ derivative, VH1000 (provided by M.S. Thomas), as hosts.

Plasmids, bacteriophages and gene fusions.

A ColE1-like plasmid, pBR322 (Bolivar et al., 1977), was used. A standard, wild-type bacteriophage λ plasmid, pKB2 (Kur et al., 1987), was used to express oop RNA. For production of truncated and His-tagged poly(A) polymerase I (His6-PAPI-L), plasmid pQPAPL was constructed by PCR amplification of an E. coli MG1655 chromosome fragment using Pfu DNA polymerase (Fermentas) and primers PCNLATG (5′-CAGAATTCATTAAAGAGGAGCTGAAGGTAATGTACAGGCTC-3′) and PCNLKON (5′-CATAGATCTTGCGGTACCCTCACGACGTGG-3′), digestion of the PCR product with BglII and EcoRI, and its insertion into corresponding restriction sites of the pQE60 vector (Qiagen). Plasmid pHG-ppcnB, bearing a multicopy ppcnB–lacZ fusion, was constructed by cloning a PCR-amplified DNA fragment containing a region of the putative pcnB promoter into the BamHI and EcoRI sites of the pHG86 plasmid (Giladi et al., 1992). The PCR reaction was performed using the following primers: PCNE (5′-ATGGATCCCACCGT CACCTGTGGAC) and PCNECO (5′-tagaattcatgctgagct atgattagccgc). To construct a single-copy ppcnB-lacZ fusion plasmid, in vivo recombination between phage vector λB299 (Giladi et al., 1995) and plasmid pHG-ppcnB was performed according to a previously described procedure (Giladi et al., 1995). The phage strain carrying the ppcnB–lacZ fusion was then used for lysogenization of strain VH1000. The presence of a single copy fusion in the host (VH1000-ppcnB–lacZ) chromosome was verified using a PCR-based method (described in Powell et al., 1994).

Culture media and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains were cultured at 37 °C in media supporting different growth rates (Table 1). Luria–Bertani (LB) medium (Sambrook et al., 1989) and different minimal media were used. The minimal media contained salts (per litre of the medium: 6.0 g Tris, 5.8 g maleic acid, 2.5 g NaCl, 2.0 g KCl, 1.0 g NH4Cl, 1.0 g MgCl2·6H2O, 0.132 g Na2SO4, 0.322 g Na2HPO4·12H2O; pH 7.2), 0.01 g l−1 thiamine, and different carbon sources (one of the following: 2 g l−1 glucose (MMGlu), 2 g l−1 glycerol (MMGly), 6 g l−1 sodium succinate (MMSuc) or 8 g l−1 sodium acetate (MMAce)). When appropriate, kanamycin (up to 25 μg ml−1) and/or ampicillin (up to 50 μg ml−1) were added.

Isolation of total RNA and reverse transcription.

A sample of bacterial culture was centrifuged and the pellet was frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was isolated using Total RNA Prep Plus kit (A&A Biotechnology) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA (1 μg) was used, along with one of the primers described in the next section, for the first-strand complementary DNA synthesis, which was catalysed by Moloney Murine Leukaemia virus reverse transcriptase (Fermentas) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

Quantification of polyadenylated RNA by RT–PCR.

The percentages of polyadenylated lpp and oop transcripts were determined using the kinetic RT–PCR method (Ferre et al., 1996). Total RNA (1 μg) was used in reverse transcription reactions using the poly(T) primer, (T)18, which results in the production only of cDNAs reverse-transcribed from polyadenylated RNAs, and 3′ end genespecific primers (REVLPP: 5′-TGTTGTCCAGACGCTGGTTAGCACGAG-3′ for lpp, and REVOOP: 5′-CGGCGGCAACCGAG-3′ for oop), which amplify the gene-specific total cDNA, including both polyadenylated and non-polyadenylated transcripts. These cDNAs were amplified in separate RT–PCR reactions using a 5′-specific primer for either lpp (LPP1: 5′-TGGTACTGGGCGCGGTAATCCTG-3′) or oop (OOP2: 5′-GTTGATAGATCCAGTAATGACCTCAG-3′) and the 3′-specific primer (REVLPP for lpp or REVOOP for oop). During the exponential phase of the PCR, amplified products were run on a 6% polyacrylamide gel in TBE buffer (Sambrook et al., 1989), and the gel was stained with ethidium bromide. Quantification of band densities was performed in the Kodak Digital Science 1D system. The percentage of polyadenylated RNA was calculated based on the densitometrically determined values obtained from poly(A)-dependent cDNA versus total cDNA.

Overproduction and purification of the truncated and His-tagged poly(A) polymerase I (His6-PAP I-L).

The E. coli JM109 strain (Yanisch-Perron et al., 1985) bearing pQPAPL was grown at 37 °C in LB medium supplemented with ampicillin (50 μg ml−1) until the culture reached an A578 of 0.3. The culture was then induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside for 2 h. The truncated and His-tagged poly(A) polymerase I (His6-PAPI-L) was purified under denaturing conditions using Ni2+-nitrilotriacetate affinity chromatography (Qiagen), in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

Production and testing of anti-PAP I serum.

Purified His6-PAPI-L protein was dialysed against 0.9% NaCl. This protein (0.5 mg) was used for immunization of a rabbit as described by Harlow & Lane (1988). The anti-PAP I serum obtained was tested by western blotting with protein lysates of an E. coli wild-type (MG1655) strain and its ΔpcnB::kan derivative (Wróbel et al., 1998).

Western blotting analysis.

Samples of equal bacterial mass (corresponding to an A578 of 0.4) were collected by centrifugation (4,000g for 10 min) and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Cell lysates, prepared by boiling of cells in loading buffer (Sambrook et al., 1989), were separated electrophoretically in SDS–polyacrylamide gels and proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The proteins were detected using ECL Western-blot detection reagents (Amersham Life Science) and a PhosphorImager (Bio-Rad). Bands were quantified using the Kodak Digital Science 1D system.

Estimation of β-galactosidase activity.

Activity of β-galactosidase in E. coli cells was estimated according to Miller (1972).

Estimation of RNA degradation rates.

Bacteria carrying either pBR322 or pKB2 plasmids were grown in various media to mid-log phase. Rifampicin was added up to 200 μg ml−1 to inhibit transcription. Samples were withdrawn at different times, total RNA was isolated as described above, and amounts of specific transcripts were determined by primer extension as described previously (Hajnsdorf et al., 1995), using the genespecific primers REVOOP for oop and COLREV (5′-TACCAACGGTG GTTTGTTTGCCGG) for RNA I.

Estimation of plasmid copy number.

Plasmid copy number in bacteria growing in different media was estimated as described previously (Wȩ grzyn et al., 1996).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Polish State Committee for Scientific Research (project 6 P04A 016 16). G.W. acknowledges financial support from the Foundation for Polish Science (subsidy 14/2000).

References

- August J., Ortiz P.J. & Hurwitz J. (1962) Ribonucleic acid-dependent ribonucleotide incorporation. I. Purification and properties of the enzyme. J. Biol. Chem., 237, 3786–3793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binns N. & Masters M. (2002) Expression of the Escherichia coli pcnB gene is translationally limited using an inefficient start codon: a second chromosomal example of translation initiated at AUU. Mol. Microbiol., 44, 1287–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum E., Carpousis A.J. & Higgins C.F. (1999) Polyadenylation promotes degradation of 3′structured RNA by the Escherichia coli mRNA degradosome in vitro. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 4009–4016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolivar F. et al. (1977) Construction and characterization of new cloning vehicles. II. A multipurpose cloning system. Gene, 2, 95–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao G.-J. & Sarkar N. (1992a) Identification of the gene for an Escherichia coli poly(A) polymerase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 10380–10384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao G.-J. & Sarkar N. (1992b) Poly(A) RNA in Escherichia coli: nucleotide sequence at the junction of the lpp transcript and the polyadenylate moiety. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 7546–7550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpousis A.J., Vanzo N.F. & Raynal L.C. (1999) mRNA degradation: a tale of poly(A) and multiprotein machines. Trends Genet., 15, 24–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coburn G.A. & Mackie G.A. (1999) Degradation of mRNA in Escherichia coli: an old problem with some new twists. Prog. Nucleic Acids Res. Mol. Biol., 62, 55–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y. & Cohen S.N. (2000) Unpaired terminal nucleotides and 5′ monophosphorylation govern 3′ polyadenylation by Escherichia coli poly(A) polymerase I. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 79, 6415–6420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferre F., Pezzoli P. & Buxton E. (1996) In A Laboratory Guide to RNA (ed.Krieg, P.A.) 175–190. Willey–Liss, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Gabig M. et al. (1998) Excess production of phage λ delayed early proteins under conditions supporting high Escherichia coli growth rates. Microbiology, 144, 2217–2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giladi H., Koby S., Gottesman M.E. & Oppenheim A.B. (1992) Supercoiling, integration host factor, and a dual promoter system participate in the control of the bacteriophage λ pL promoter. J. Mol. Biol., 224, 937–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giladi H., Goldenberg D., Koby S. & Oppenheim A.B. (1995) Enhanced activity of the bacteriophage λ PL promoter at low temperature. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 92, 2184–2188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadas H., Einav M., Fishov I. & Zaritsky A. (1997) Bacteriophage T4 development depends on the physiology of its host Escherichia coli. Microbiology, 143, 179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajnsdorf E., Braun F., Haugel-Nielsen J. & Regnier P. (1995) Polyadenylation destabilizes the rpsO mRNA of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 92, 3973–3977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow E. & Lane D. (1988) Antibodies: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen K.F. (1993) The Escherichia coli 'wild types' W3110 and MG1655 have an rph frame shift mutation that leads to pyrimidine starvation due to low pyrE expression levels. J. Bacteriol., 175, 3401–3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kur J., Górska I. & Taylor K. (1987) Escherichia coli dnaA initiation function is required for replication of plasmids derived from coliphage lambda. J. Mol. Biol., 198, 203–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J.H. (1972) Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty B.K. & Kushner S.R. (1999a) Analysis of the function of Escherichia coli poly(A) polymerase I in RNA metabolism. Mol. Microbiol., 34, 1094–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty B.K. & Kushner S.R. (1999b) Residual polyadenylation in poly(A) polymerase I (pcnB) mutants of Escherichia coli does not result from the activity encoded by the f310 gene. Mol. Microbiol., 34, 1109–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty B.K. & Kushner S.R. (2000) Polynucleotide phosphorylase, RNase II and RNase E play different roles in the in vivo modulation of polyadenylation in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol., 36, 982–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson G., Belasco J.G., Cohen S.N. & von Gabain A. (1984) Growth-rate dependent regulation of mRNA stability in Escherichia coli. Nature, 312, 75–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hara E.B. et al. (1995) Polyadenylation helps regulate mRNA decay in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 92, 1807–1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell B.S., Court D.L., Nakamura Y., Rivas M. & Turnbough C.L. Jr (1994) Rapid confirmation of single copy lambda prophage integration by PCR. Nucleic Acids Res., 22, 5765–5766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauhut R. & Klug G. (1999) mRNA degradation in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev., 23, 353–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regnier P. & Arraiano C.M. (2000) Degradation of mRNA in bacteria: emergence of ubiquitous features. BioEssays, 22, 235–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Fritsch E.F. & Maniatis T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Mannual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar N. (1996) Polyadenylation of mRNA in bacteria. Microbiology, 142, 3125–3133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szalewska-Pałasz A., Wróbel B. & Wȩgrzyn G. (1998) Rapid degradation of polyadenylated oop RNA. FEBS Lett., 432, 70–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steege D.A. (2000) Emerging features of mRNA decay in bacteria. RNA, 6, 1079–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wȩgrzyn G., Wȩgrzyn A., Pankiewicz A. & Taylor K. (1996) Allele specificity of the Escherichia coli dnaA gene function in the replication of plasmids derived from phage λ. Mol. Gen. Genet., 252, 580–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wȩgrzyn A., Czyz A., Gabig A. & Wȩgrzyn G. (2000) ClpP/ClpX-mediated degradation of the bacteriophage λ O protein and regulation of λ phage and λ plasmid replication. Arch. Microbiol., 174, 89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wróbel B., Herman-Antosiewicz A., Szalewska-Palasz A. & Wȩgrzyn G. (1998) Polyadenylation of oop RNA in the regulation of bacteriophage λ development. Gene, 212, 57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F. & Cohen S.N. (1995) RNA degradation in Escherichia coli regulated by 3′ adenylation and 5′ phosphorylation. Nature, 374, 180–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F., Gaggero C. & Cohen S.N. (2002) Polyadenylation can regulate ColE1 type plasmid copy number independently of any effect on RNAI decay by decreasing the interaction of antisense RNAI with its RNAII target. Plasmid, 48, 49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanisch-Perron C., Vieira J. & Messing J. (1985) Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene, 33, 103–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehudai-Resheff S. & Schuster G. (2000) Characterization of the E. coli poly(A) polymerase: nucleotide specificity, RNA-binding affinities and RNA structure dependence. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 1139–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]