Abstract

Autographa californica multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV), a prototype member of the Baculoviridae family, has gained increasing interest as a potential vector candidate for mammalian gene delivery applications. AcMNPV is known to enter both dividing and nondividing mammalian cell lines in vitro, but the mode and kinetics of entry as well as the intracellular transport of the virus in mammalian cells is poorly understood. The general objective of this study was to characterize the entry steps of AcMNPV- and green fluorescent protein-displaying recombinant baculoviruses in human hepatoma cells. The viruses were found to bind and transduce the cell line efficiently, and electron microscopy studies revealed that virions were located on the cell surface in pits with an electron-dense coating resembling clathrin. In addition, virus particles were found in larger noncoated plasma membrane invaginations and in intracellular vesicles resembling macropinosomes. In double-labeling experiments, virus particles were detected by confocal microscopy in early endosomes at 30 min and in late endosomes starting at 45 min posttransduction. Viruses were also seen in structures specific for early endosomal as well as late endosomal/lysosomal markers by nanogold preembedding immunoelectron microscopy. No indication of viral entry into recycling endosomes or the Golgi complex was observed by confocal microscopy. In conclusion, these results suggest that AcMNPV enters mammalian cells via clathrin-mediated endocytosis and possibly via macropinocytosis. Thus, the data presented here should enable future design of baculovirus vectors suitable for more specific and enhanced delivery of genetic material into mammalian cells.

At present, viral vectors appear to be the most efficient tools for gene delivery applications, with a promising newcomer being Autographa californica multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV), a member of the Baculoviridae family. The host specificity of baculovirus was long supposed to be restricted to arthropods until Volkman and Goldsmith (53) showed that the viruses were efficiently taken up by mammalian cells. Later, Hofmann and colleagues (22) reported that the recombinant baculoviruses were also able to deliver genes into human hepatocytes. Since then, baculovirus has been shown to transduce a variety of both dividing and nondividing mammalian cells in vitro with significant efficiency resulting in stable foreign gene expression depending on the promoter (8, 39, 42, 48, 49). Although crucial for development of baculovirus-based gene therapy vectors, entry of baculovirus into mammalian cells is still poorly understood.

Autographa californica multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV) is an enveloped lepidopteran insect virus with a circular double-stranded DNA genome (∼134 kb) and a rod-shaped nucleocapsid. The sequence of the viral genome has been determined (3), whereas the detailed structure of the virion has been only partially described. The major protein of the viral nucleocapsid is vp39, whereas that of the envelope is the viral glycoprotein gp64 (9). The infection of budded virus (AcMNPV) in Spodoptera frugiperda cell culture is thought to represent general secondary infection in the insect host. Baculovirus has been shown to enter insect cells via adsorptive endocytosis (6, 54, 55), with the uptake to intracellular vesicles occurring between 10 and 20 min postinfection. The cellular receptor, however, has not been identified. The nucleocapsids are further released from endosomes between 15 and 30 min postinfection. (6, 19, 25, 32, 51) with the help of the baculovirus membrane protein gp64 (7). After uncoating, the nucleocapsid induces the formation of actin filaments in the cytoplasm and is transported towards the nucleus (10, 26). Finally, nucleocapsids interact with the nuclear pore, enter the nucleus, and uncoat (18, 56).

Entry of baculovirus to mammalian cells has been thought to be similar to that found in insect cells. Cell surface molecule interactions with baculovirus during uptake in mammalian cells are unclear; however, the virus has been suggested to use rather widely distributed and heterogeneous cell surface motifs (14). The first evidence for use of the endosomal pathway during baculovirus entry was provided by transducing cells in the presence of chloroquine, bafilomycin A1, and ammonium chloride, which all strongly prevented viral transduction (8, 22, 42, 52). Further, the baculovirus envelope and the early endosomal membrane were proposed to fuse (25, 52), presumably with help from the major viral membrane glycoprotein gp64. After endosomal escape, the nucleocapsid has been suggested to be transported into the nucleus by actin filaments, both viral capsids, and genome traversing through nuclear pores (25, 46).

Baculovirus vectors have emerged as promising for gene delivery to mammalian cells of different origin, especially human hepatocytes (4, 8, 12, 22, 52). Similar levels of expression have been observed for both baculovirus and replication-defensive adenovirus vectors (1, 27, 48). Baculovirus is also unable to replicate in mammalian cells (53) and can accommodate large foreign DNA inserts (>50kb) and be amplified to high titers (11, 13, 38). Baculovirus-mediated transduction in vivo, however, has been hampered due to inactivation by serum complement (23, 50). Targeting of baculovirus to mammalian cells, improved by genetic engineering of the viral surface, has therefore become important for in vivo gene therapy strategies (17, 24, 36, 37, 39, 40, 43, 45).

The entry routes of viruses used for gene therapy purposes should be known for future development of safe gene transfer systems. In the present study, we have characterized the entry of baculovirus (AcMNPV) in detail using the human hepatoma cell line (HepG2). Viral detection was carried out by various confocal and electron microscopy techniques, including nanogold preembedding labeling. To our knowledge, these studies provide the first direct evidence of baculovirus entry via clathrin-mediated endocytosis into mammalian cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

The Spodoptera frugiperda insect cell line (Sf9) was grown in monolayer or suspension cultures at +27°C in serum-free HyQSFX-insect medium (HyClone Inc., Logan, UT) in the absence of antibiotics. The human hepatoma cell line (HepG2) was grown in monolayer cultures in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), penicillin-streptomycin, and l-glutamine at +37°C in 5% CO2 (Gibco BRL, Paisley, United Kingdom). Wild type, Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV), and recombinant baculoviruses vp39EGFP (25) and AcCMVEGFP (16) were used. The virus titers were determined by end point dilution assays using Sf9 cells (38).

Antibodies.

The antibodies directed against AcMNPV gp64 monoclonal antibody (B12D5) and vp39 (p10C6) were kindly provided by L. Volkman (University of California, Berkeley, CA). The mouse monoclonal antibody against early endosome antigen 1 (EEA-1) and the monoclonal antibody against Golgi-matrix protein (GM130) were from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY). The polyclonal antibody against recycling early endosomes (Rab11) and the monoclonal antibody against late endosomal/lysosomal protein CD63 were from Zymed Laboratories (South San Francisco, CA). The polyclonal antibody against late endosomes, cation-independent mannose-6-phosphate receptor (CI-MPR) has been described previously (31). The monoclonal antibody against the trans-Golgi network (TGN-38) was a generous gift from G. Banting (University Walk, Bristol BS8 1TD, United Kingdom). In double-labeling experiments, Alexa-546-conjugated anti-mouse antibody and Alexa-488-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody were used (Molecular Probes Inc., Eugene, OR). Nanogold-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Ladd Research Industries (Williston, VT).

Transduction of HepG2 cells.

For internalization studies, HepG2 cells were grown to subconfluency on coverslips or plates for 2 days at +37°C. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) on ice, cells were transduced with wild-type virus (multiplicity of infection [MOI] of 80 to 100 for confocal microscopy or MOI of 500 to 1,000 for electron microscopy) or vp39EGFP (MOI of 200 for confocal microscopy) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 1% FCS on ice for 1 h. Cells were washed with 1.5% bovine serum albumin-PBS on ice and incubated further in DMEM containing 10% FCS at +37°C. At set time intervals posttransduction (0 to 4 h), cells were fixed for confocal microscopy either with methanol (on ice for 6 min) or with 4% paraformal dehyde (PFA) in PBS (at room temperature [RT] for 20 min) and, for electron microscopy, cells were fixed with periodate-lysine-PFA fixative (PLP) at +4°C on (4% PFA, 75 mM lysine-HCl-Na-phosphate buffer, 2.13 mg/ml NaIO4). In the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) expression studies, cells were transduced with AcCMVEGFP virus (MOI of 90) in DMEM containing 10% FCS at +37°C for 2 to 24 h and fixed with 4% PFA in PBS.

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy.

After transduction and fixation, analysis of immunofluorescence stainings was performed depending on the fixing method, and coverslips were embedded in Mowiol-DABCO (25 mg/ml). The samples were examined with a laser-scanning confocal microscope (LSM 510; Zeiss Axiovert 100 M) by using appropriate excitation and emission settings. For double-labeling experiments, multitracking for 488- and 546-nm laser lines was used to avoid false colocalization.

Nanogold preembedding immunoelectron microscopy.

For the electron microscopy studies, HepG2 cells were grown to subconfluency and transduced and fixed as described above. After fixing, cells were washed with phosphate buffer (0.1 M Na2HPO4, pH 7.4) and permeabilized with saponin buffer (0.01% saponin-0.1% bovine serum albumin-0.1 M Na2HPO4). Cells were incubated with appropriate primary and nanogold-conjugated secondary antibodies at RT for 1 h, both diluted in saponin buffer. After the washes with saponin and the phosphate buffers, the postfixation (1% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer) and quenching (50 mM NH4CL in Na2HPO4) were performed, followed by silver enhancement (Nanoprobes, Yaphank, N.Y.) and gold toning (2% Na-acetate, 0.05% HAuCl4, and 0.3% Na-thiosulphate in H2O). The cells were further postfixed [1% osmium tetroxide, 0.1 M phosphate buffer, K4Fe(CN)6 15 mg/ml] at +4°C for 1 h and dehydrated with 70% and 96% ethanol, stained with 2% uranylacetate, and embedded in LX-112 Epon [Ladd Research Industries, Williston, VT]. Polymerization was performed during 24 h, first at +45°C and then at +60°C. The samples were further stained with toluidine blue, cut with ultramicrotome (Reichert-Jung; Ultracut E) and stained with uranylacetate and lead citrate. The examination was performed with a JEOL JEM-1200EX transmission electron microscope operated at ∼60 kV.

Ruthenium red staining for electron microscopy.

After transduction, cells were washed (cacodylate buffer, pH 7.3), fixed, and stained with 1.3% glutaraldehyde and 0.07 mg/ml ruthenium red in cacodylate buffer at RT for 1 h. The cells were postfixed with 1.7% osmium tetroxide containing 0.07 mg/ml ruthenium red (in cacodylate buffer, pH 7.3, for 3 h RT), dehydrated in 70% and 96% ethanol, stained with 2% uranylacetate, and embedded in LX-112 Epon. Polymerization, further staining, and cutting was carried out as described above.

RESULTS

General course of baculovirus transduction.

It has been previously shown that baculovirus transduces HepG2 cells efficiently (4, 8, 12, 22, 52). In this study, the internalization and intracellular localization of wild-type, CMVEGFP, and vp39EGFP baculoviruses were detected in HepG2 cells by confocal and electron microscopy.

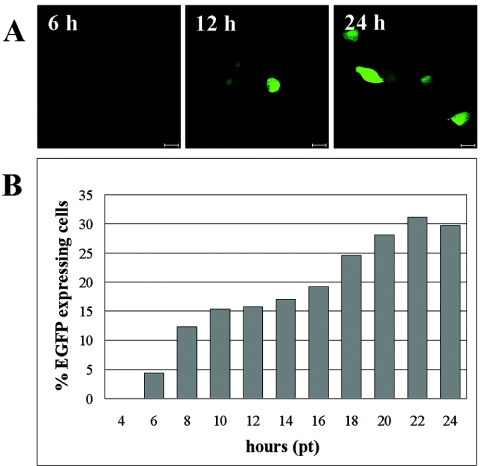

To study the general course of baculovirus entry into HepG2 cells, a recombinant baculovirus, AcCMVEGFP (16), expressing EGFP under a cytomegalovirus promoter was used. As shown by quantitative analysis, EGFP expression was first detected at 6 h posttransduction (p.t.), in which approximately 3% of the transduced cells were positive (Fig. 1A and B). A significant increase in expression was observed at 12 h p.t., with the maximum level being reached at 22 h p.t. At this time point, approximately 30% of the transduced cells expressed EGFP.

FIG. 1.

Expression of EGFP in AcCMVEGFP-transduced HepG2 cells. (A) Confocal microscopy images of cells expressing EGFP at 6, 12, and 24 h p.t. Bar, 20 μm. (B) Time scale representation of the percentage of cells expressing EGFP. Cells were fixed at indicated time points and analyzed visually by confocal microscopy (n, <300).

Cellular binding of baculoviruses.

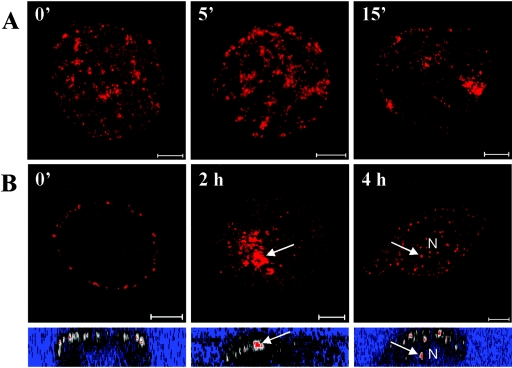

In confocal microscopy, wild-type baculoviruses labeled with nucleocapsid antibody vp39 were used to monitor the cell surface binding to HepG2 cells. In these studies, viruses were shown to bind to all HepG2 cells efficiently, concentrating on certain areas of the plasma membrane. At 5 to 15 min p.t., distinct cluster formations of viruses on or nearby the plasma membrane were observed (Fig. 2A). After 30 min p.t., virus was increasingly detected in perinuclear accumulations, which were most clear during 1 to 2 h p.t. (Fig. 2B). At later time points (3 to 4 h p.t.), viral capsids were seen in the nucleus, although a substantial number of viral capsids remained in the cytoplasm.

FIG. 2.

(A) Viral cluster formation on the HepG2 cell surface at 0 to 15 min p.t. detected with viral capsid vp39 antibody. Pictures are surface projections from confocal z stacks of the cell. 0′, 0 min; 5′, 5 min; 15′, 15 min. Bar, 5 μm. (B) Overview of baculovirus entry in HepG2 cells when visualized with the viral capsid vp39 antibody. The upper images indicate viral capsids on the cell surface and accumulation in the cytoplasm (arrow, 2 h) and in the nucleus at 4 h p.t. (arrow). Pictures are projections of 2 to 6 individual slices of z stacks inside the cell. The lower images indicate the intracellular localization of the viruses in orthogonal cut (color palette range indicator style). N, nucleus. 0′, 0 min. Bar, 5 μm.

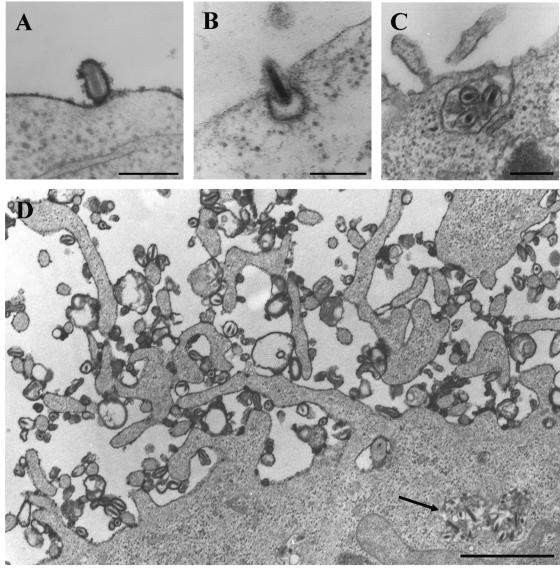

Binding of baculovirus to HepG2 cells was further observed using electron microscopy (EM) with ruthenium red staining (Fig. 3A) and nanogold preembedding labeling. Due to the large size of the baculovirus particles, visualization by EM without immunolabeling of the capsid was possible (46, 52). In this study, unlabeled electron micrographs showed that wild-type baculovirus, having a typical rod-shaped morphology surrounded by a characteristically loose-fitting envelope, was abundantly seen near the plasma membrane starting at 15 to 30 min p.t. By further analysis with ruthenium red (30), which stains the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane and extracellular-enveloped baculovirus, virus particles were frequently seen attached to microvilli-like structures (Fig. 3D). Interestingly, these structures were more abundantly seen in transduced cells relative to untransduced control cells.

FIG. 3.

Baculovirus entry in HepG2 cells analyzed by electron microscopy. (A) Baculovirus bound to the cell surface at 30 min p.t.; plasma membrane densely stained with ruthenium red. Bar, 200 nm. (B) Baculovirus bound to the cell surface in a pit with an electron-dense coating resembling clathrin at 30 min p.t. Bar, 200 nm. (C) Baculoviruses in a large plasma membrane invagination at 1.5 h p.t. Bar, 200 nm. (D) Baculoviruses are on the cell surface in an area containing microvillus-like structures and near the plasma membrane in large intracellular vesicles at 30 min p.t. (arrow), with dense ruthenium red staining indicating the cell surface. Bar, 1 μm.

Cellular uptake of baculoviruses.

Many viruses are known to internalize via clathrin-mediated endocytosis (41). Although baculovirus has been suggested to use this endocytosis route, no direct evidence has yet been presented to our knowledge. Here, the internalization of baculovirus was further detected at various time points by electron microscopy, in which clathrin-coated pits were clearly visible without antibody labeling by the characteristic bristle density seen on the cytosolic side of coated membranes (33). Starting at 30 min p.t., some baculoviruses were seen at the cell surface in pits with an electron-dense coating resembling clathrin (Fig. 3B). At this time point, virus was also seen near the plasma membrane in small noncoated cytoplasmic vesicles. However, no viruses in clathrin-coated vesicles were found. Interestingly, EM studies revealed that virus particles also were observed in larger noncoated plasma membrane invaginations and in larger vesicles near the cell surface at 30 min p.t. (Fig. 3C). This was confirmed by ruthenium red staining, which showed that the invaginations were not contiguous with the plasma membrane, but were actually cytoplasmic vesicles containing several virus particles (Fig. 3D).

Endocytic compartments in baculovirus entry.

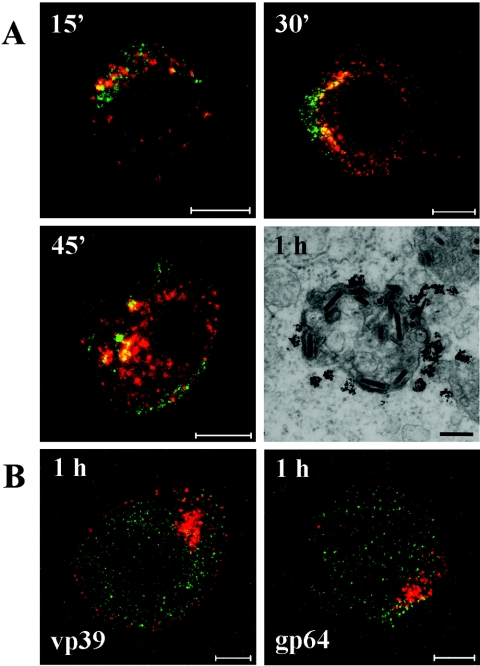

To further study baculovirus entry, different endocytic markers were used. In confocal microscopy, baculovirus displaying EGFP as a fusion to the capsid protein vp39 (vp39EGFP) (25) was shown to colocalize markedly with an early endosomal marker (EEA-1) from 15 min up to 1 h p.t. (Fig. 4A). Maximum colocalization was estimated visually to take place at 30 to 45 min p.t. Colocalization was not further observed after 1.5 h p.t. In addition, by using nanogold preembedding immunoelectron microscopy, virus particles were detected in structures that were positive for EEA-1 from 30 min to 1.5 h p.t.

FIG. 4.

(A) Baculovirus capsid fusion protein vp39EGFP (green) colocalizes with the early endosomal marker EEA-1 (red) at 15 (15′), 30 (30′), and 45 (45′) min p.t. Bar, 10 μm. Baculoviruses in a vesicle are positive for the early endosomal marker EEA-1 stained with the nanogold preembedding electron microscopy at 1 h p.t. Bar, 200 nm. (B) The baculovirus capsid protein vp39 (red) or membrane glycoprotein gp64 (red) did not colocalize (yellow) with the marker (Rab11) for recycling early endosomes (green) at 1 h p.t. when analyzed by confocal microscopy. Bar, 5 μm.

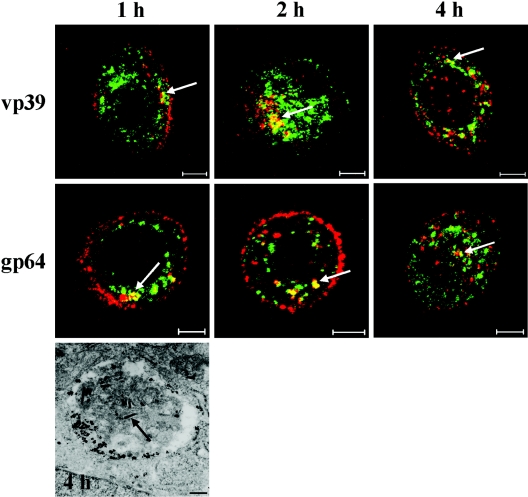

In further immunolabeling studies of transduced cells, where the virus was identified with antibodies against the vp39 capsid protein or gp64 membrane protein, samples were colabeled with markers for recycling early endosomes, late endosomes, lysosomes, and the Golgi complex. In confocal microscopy, no colocalization of virus and recycling early endosomes (anti-rab11, Fig. 4B) or the Golgi complex (anti-TGN-38, anti-GM130, data not shown) was observed during 4 h p.t. Interestingly, the late endosomal marker, CI-MPR, showed partial colocalization with the virus (anti-vp39 and anti-gp64) starting at 45 min p.t (Fig. 5). Maximum colocalization of labeled baculoviruses with late endosomes was estimated visually to take place at 1.5 h p.t. At later time points, colocalization with the viral capsid vp39 started to decrease, while the viral envelope glycoprotein gp64 stayed clearly colocalized. The presence of baculoviruses in these endosomal compartments was confirmed by nanogold immunoelectron microscopy, which showed enveloped virus particles in structures that were positive for the late endosomal/lysosomal membrane glycoprotein CD63 at 2 to 4 h p.t.

FIG. 5.

Colocalization (yellow) of baculovirus capsid protein vp39 (red) or membrane protein gp64 (red) with a late endosomal marker (arrow) CI-MPR (green) at 1, 2, and 4 h p.t. Bar, 5 μm. Baculoviruses (arrows) in an intracellular vesicle are positive for the late endosomal/lysosomal marker CD63 stained with the nanogold preembedding electron microscopy at 4 h p.t. Bar, 200 nm.

DISCUSSION

Knowledge of the interaction of baculovirus with mammalian cells is essential for the development of baculovirus-based gene delivery vectors. So far, baculovirus vectors have been shown to transduce various dividing and nondividing mammalian cell lines in vitro (1, 8, 12, 20, 29, 42, 48, 49, 52). Baculovirus-mediated gene transfer has also been successful in vivo (1, 21, 23, 24, 27, 42, 47, 48, 50). Several important aspects of baculovirus entry to mammalian cells, however, have not been studied in detail. A receptor has not been identified, and the mode and kinetics of entry and intracellular transport are unknown. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to characterize the internalization and intracellular localization of baculovirus in human hepatoma cells (HepG2).

Numerous studies have previously demonstrated that baculovirus is able to transduce various hepatoma cell lines efficiently and HepG2 cells preferentially (4, 8, 12, 22, 52). Recently, baculovirus nucleocapsids were shown in early endosomes at 30 min p.t. (25) and in the cytoplasm or the nucleus of HepG2 cells at 4 to 6 h p.t. (25, 46). In this study, particularly the early entry phase of baculovirus transduction was investigated. In general, baculovirus entry seemed to be a relatively slow and nonsimultaneous process. By confocal and electron microscopy, baculovirus particles were seen on the cell surface at 0 to 30 min p.t. (Fig. 2A, 3A, and 3D) and, later, enveloped nucleocapsids were seen in intracellular vesicles (Fig. 3D, 4A, and 5). Baculovirus capsids were also detected inside the nucleus (Fig. 2B) although relatively large amounts of virus remained in the cytoplasm. In addition, quantitative analysis using confocal microscopy revealed that expression of EGFP was first detected at 6 h p.t. when the recombinant AcCMVEGFP baculovirus was used. The maximum level of EGFP expression, approximately 30% of cells, was reached at 22 h p.t. (Fig. 1A and 1B), being consistent with the report of Salminen et al. (46), in which 20% of transduced HepG2 cells were shown to produce β-galactosidase at 24 h p.t.

The early events of a viral infection include attachment of the virion to the receptor followed by entry into the cell and subsequent release of the genome. Despite numerous efforts, the natural receptor for baculovirus has not yet been discovered. Because of the wide range of mammalian cells that are susceptible to baculovirus transduction, it is likely that the target molecule is a relatively universal cell surface component, possibly heparan sulfate or even a phospholipid (14, 45, 51). Involvement of the viral envelope glycoprotein gp64 has also been proposed (7, 19, 54). In fact, Tani et al. (51) suggested that the interaction of gp64 and phospholipids on the cell surface might be involved in binding or penetration of baculovirus into mammalian cells. In this study, clustering of virus particles at certain areas of the cell surface was evident at 5 to 15 min p.t. using surface projection in confocal microscopy (Fig. 2A). Moreover, the accumulation and the internalization of viral clusters during the first 20 min p.t. were clearly detectable in preliminary live-cell imaging experiments (data not shown). These findings may indicate that baculovirus accumulates at specific receptors or areas with high endocytic activity (15) on the plasma membrane. Together, baculovirus seems to concentrate on certain areas on the HepG2 cell surface and these clusters seem to internalize with time.

Volkman and Goldsmith (54) were the first to report that baculovirus enters insect cells via adsorptive endocytosis, likely via the clathrin-mediated pathway. Baculovirus was also seen in cytoplasmic vesicles by electron microscopy in Pk1 and HepG2 cells (46, 52) and more specifically in early endosomes in HepG2 cells (25). However, no other direct evidence of the use of the clathrin-mediated pathway in baculovirus entry to mammalian cells has been published. Here, baculovirus was, to our knowledge, seen for the first time in clathrin-coated pits by electron microscopy on the surface of HepG2 cells at 30 min p.t. (Fig. 3B). Clathrin-coated vesicles containing viruses, however, were not found, although small noncoated vesicles near the cell membrane were detected. This might be due to the quick disassembly of the clathrin coat after pinching (35). In conclusion, these data indicate that baculovirus uses at least clathrin-mediated endocytosis as one of its entry pathways to HepG2 cells. However, baculovirus attachment to clathrin-coated pits seemed to be a relatively rare phenomenon, and therefore other internalization mechanisms could also coexist.

Clathrin-mediated endocytosis is known to lead to early and late endosomes, and finally to lysosomes (35). So far, many different viruses have been shown to utilize this pathway for release of the viral capsid to the cytoplasm from the early or late endosomes in mammalian cells (41). The baculovirus envelope has also been suggested to fuse with the early endosomal membrane at about 1 h p.t. under mildly acidic conditions with the help of the viral protein gp64, after which the capsid is released to the cytoplasm (52). Recent data by Kukkonen and coworkers (25) suggests that baculovirus escapes from early endosomes after 30 min p.t., since inhibition of the early endosome acidification by monensin led to the block of baculovirus capsid escape from EEA1-positive early endosomes into the cytoplasm. In this study, the role of early endosomes in baculovirus entry was further studied by using immunofluorescence labeling with an early endosome marker, EEA1, and vp39EGFP as well as by nanogold preembedding labeling electron microscopy. In these experiments, enveloped baculovirus particles were shown in early endosomes starting at 30 min p.t. (Fig. 4A). No virus, however, was seen in these structures after 1.5 h p.t. or in recycling early endosomes (Fig. 4B), presumably indicating that the virus was already transported to other cell compartments or that the capsid had escaped to the cytosol. To study the endosomal escape and to distinguish the time point of capsid release from the intracellular vesicles, immunofluorescence labeling was performed with both anti-gp64 and anti-vp39 antibodies. The late endosomal marker, CI-MPR, and wild-type baculovirus labeled with anti-vp39 or anti-gp64 started to colocalize at 45 min p.t. (Fig. 5) with a maximum at 1.5 h p.t. All internalized virus, however, did not colocalize with the late endosomal marker, but rather was seen near the nuclear area, suggesting that some virus particles were already released before entering the late endosomes and/or had proceeded to the later structures of the clathrin pathway. Also, in the nanogold preembedding immunolabeling experiments, enveloped baculoviruses were seen at 2 to 4 h p.t. in intracellular vesicles labeled with the late endosomal/lysosomal marker CD63. These results suggest that some virus is also transported to lysosomes and degraded.

The size difference between clathrin-coated vesicles (100 to 150 nm; (35) and baculoviruses (25 × 260 nm) is likely to restrict viral entry via clathrin-mediated endocytosis into mammalian cells. In a recent report by Rejman and collaborators (44), clathrin vesicles were suggested to have an upper size limit of approximately 200 nm. In this study, other possible baculovirus entry routes were therefore investigated by electron microscopy. In addition to clathrin-coated pits, baculovirus was found in larger plasma membrane invaginations at the cell surface containing several enveloped viruses (Fig. 3C). Importantly, the sizes of these vesicles were comparable to the size of macropinosomes, being 0.5 to 2.0 μm in diameter (5). Macropinocytosis, the best-studied cell-type-specific receptor-independent endocytic pathway associated with actin-dependent plasma membrane ruffling, has previously been suggested to be stimulated by some viruses to enhance acid-activated penetration from endosomes and macropinosomal vesicles (34, 41). Viruses have also been shown to induce the formation of microvilli on the cell surface (28, 34). Interestingly, Bilello et al. (4) have suggested that baculovirus entry to primary hepatocytes may require contact with the basolateral surface, which contains numerous microvilli (2). The occlusion-derived baculovirus has also been shown to fuse with the microvillar membrane of columnar epithelial cells in the highly alkaline midgut environment at low temperatures (38). In this study, baculovirus seemed to induce formation of microvilli and resided primarily on those areas of the cell surface (Fig. 3D). The higher occurrence of microvilli-like structures in virus-treated cells than in control cells may support the use of the macropinocytosis route in baculovirus entry.

Baculovirus holds great promise for the development of more efficient, safe, and specific gene therapy vectors. Understanding the molecular mechanisms of viral entry is of utmost importance for the development of gene therapy vector systems. In summary, our results suggest that baculovirus entry into human hepatoma cells is a relatively slow process, probably due to the large size of the virus. Electron microscopy analysis showed viruses at the following multiple cellular locations: at the cell surface, in clathrin-coated pits, in early endosomes, and in intracellular vesicles resembling macropinosomes. In confocal microscopy and nanogold preembedding electron microscopy, the baculovirus particles were shown to colocalize with early and late endosomal/lysosomal markers. These results suggest that baculovirus may enter mammalian cells by both clathrin-mediated endocytosis and macropinocytosis. Together, the data presented here should enable future design of baculovirus vectors suitable for specific and enhanced delivery of genetic material into human cells and tissues.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dan White, Pasi Kankaanpää, and Tuija Lehtinen for image processing assistance, Loy Volkman for baculovirus-specific antibodies, and Kari Airenne for providing the capsid display baculovirus. We are also grateful to Eila Korhonen, Pirjo Käpylä, and Salla Ruskamo for excellent technical assistance as well as to Maija Vihinen-Ranta for valuable discussions.

This work was supported by the Academy of Finland (contract 101868), the Finnish Cultural Foundation, the K. Albin Johansson Foundation, and the Finnish Research Foundation of Viral Diseases.

REFERENCES

- 1.Airenne, K. J., M. O. Hiltunen, M. P. Turunen, A. M. Turunen, O. H. Laitinen, M. S. Kulomaa, and S. Yla-Herttuala. 2000. Baculovirus-mediated periadventitial gene transfer to rabbit carotid artery. Gene Ther. 7:1499-1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arias, I., H. Popper, D. Schacter, and D. A. Shafritz. 1982. The liver: biology and pathobiology. Raven Press, New York, N.Y.

- 3.Ayres, M. D., S. C. Howard, J. Kuzio, M. Lopez-Ferber, and R. D. Posse 1994. The complete DNA sequence of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Virology 202:586-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bilello, J. P., W. E. Delaney IV, F. M. Boyce, and H. C. Isom. 2001. Transient disruption of intercellular junctions enables baculovirus entry into nondividing hepatocytes. J. Virol. 75:9857-9871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bishop, N. E. 1997. An update on non-clathrin-coated endocytosis. Rev. Med. Virol. 7:199-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blissard, G. W., and G. F. Rohrmann. 1990. Baculovirus diversity and molecular biology. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 35:127-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blissard, G. W., and J. R. Wenz. 1992. Baculovirus gp64 envelope glycoprotein is sufficient to mediate pH-dependent membrane fusion. J. Virol. 66:6829-6835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyce, F. M., and N. L. Bucher. 1996. Baculovirus-mediated gene transfer into mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:2348-2352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braunagel, S. C., and M. D. Summers 1994. Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus, PDV, and ECV viral envelopes and nucleocapsids: structural proteins, antigens, lipid and fatty acid profiles. Virology 202:315-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charlton, C. A., and L. E. Volkman. 1993. Penetration of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus nucleocapsids into IPLB Sf 21 cells induces actin cable formation. Virology 197:245-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheshenko, N., N. Krougliak, R. C. Eisensmith, and V. A. Krougliak. 2001. A novel system for the production of fully deleted adenovirus vectors that does not require helper adenovirus. Gene Ther. 8:846-854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Condreay, J. P., S. M. Witherspoon, W. C. Clay, and T. A. Kost. 1999. Transient and stable gene expression in mammalian cells transduced with a recombinant baculovirus vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:127-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies, A. H. 1994. Current methods for manipulating baculoviruses. Biotechnology (N.Y.) 12:47-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duisit, G., S. Saleun, S. Douthe, J. Barsoum, G. Chadeuf, and P. Moullier. 1999. Baculovirus vector requires electrostatic interactions including heparan sulfate for efficient gene transfer in mammalian cells. J. Gene Med. 1:93-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaidarov, I., F. Santini, R. A. Warren, and J. H. Keen. 1999. Spatial control of coated-pit dynamics in living cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 1:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilbert, L., O. Valilehto, S. Kirjavainen, P. J. Tikka, M. Mellett, P. Kapyla, C. Oker-Blom, and M. Vuento. 2005. Expression and subcellular targeting of canine parvovirus capsid proteins in baculovirus-transduced NLFK cells. FEBS Lett. 579:385-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grabherr, R., W. Ernst, C. Oker-Blom, and I. Jones. 2001. Developments in the use of baculoviruses for the surface display of complex eukaryotic proteins. Trends Biotechnol. 19:231-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Granados, R. R., K. A. Lawler, and J. P. Burand. 1981. Replication of Heliothis zea baculovirus in an insect cell line. Intervirology 16:71-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hefferon, K. L., A. G. Oomens, S. A. Monsma, C. M. Finnerty, and G. W. Blissard. 1999. Host cell receptor binding by baculovirus GP64 and kinetics of virion entry. Virology 258:455-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho, Y. C., H. C. Chen, K. C. Wang, and Y. C. Hu. 2004. Highly efficient baculovirus-mediated gene transfer into rat chondrocytes. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 88:643-651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hofmann, C., W. Lehnert, and M. Strauss. 1998. The baculovirus vector system for gene delivery into hepatocytes. Gene Ther. Mol. Biol. 1:231-239. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hofmann, C., V. Sandig, G. Jennings, M. Rudolph, P. Schlag, and M. Strauss. 1995. Efficient gene transfer into human hepatocytes by baculovirus vectors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:10099-10103.7479733 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hofmann, C., and M. Strauss. 1998. Baculovirus-mediated gene transfer in the presence of human serum or blood facilitated by inhibition of the complement system. Gene Ther. 5:531-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huser, A., M. Rudolph, and C. Hofmann. 2001. Incorporation of decay-accelerating factor into the baculovirus envelope generates complement-resistant gene transfer vectors. Nat. Biotechnol. 19:451-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kukkonen, S. P., K. J. Airenne, V. Marjomaki, O. Laitinen, P. Lehtolainen, P. Kankaanpaa, A. Mahonen, J. Raty, H. Nordlund, C. Oker-Blom, M. Kulomaa, and S. Ylä-Herttuala. 2003. Baculovirus capsid display: a novel tool for transduction imaging. Mol. Ther. 8:853-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lanier, L. M., and L. E. Volkman. 1998. Actin binding and nucleation by Autographa californica M nucleopolyhedrovirus. Virology 243:167-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lehtolainen, P., K. Tyynela, J. Kannasto, K. J. Airenne, and S. Yla-Herttuala. 2002. Baculoviruses exhibit restricted cell type specificity in rat brain: a comparison of baculovirus- and adenovirus-mediated intracerebral gene transfer in vivo. Gene Ther. 9:1693-1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu, N. Q., A. S. Lossinsky, W. Popik, X. Li, C. Gujuluva, B. Kriederman, J. Roberts, T. Pushkarsky, M. Bukrinsky, M. Witte, M. Weinand, and M. Fiala. 2002. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 enters brain microvascular endothelia by macropinocytosis dependent on lipid rafts and the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. J. Virol. 76:6689-6700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma, L., N. Tamarina, Y. Wang, A. Kuznetsov, N. Patel, C. Kending, B. J. Hering, and L. H. Philipson. 2000. Baculovirus-mediated gene transfer into pancreatic islet cells. Diabetes 49:1986-1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marechal, V., M. C. Prevost, C. Petit, E. Perret, J. M. Heard, and O. Schwartz. 2001. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry into macrophages mediated by macropinocytosis. J. Virol. 75:11166-11177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marjomaki, V. S., A. P. Huovila, M. A. Surkka, I. Jokinen, and A. Salminen. 1990. Lysosomal trafficking in rat cardiac myocytes. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 38:1155-1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Markovic, I., H. Pulyaeva, A. Sokoloff, and L. V. Chernomordik. 1998. Membrane fusion mediated by baculovirus gp64 involves assembly of stable gp64 trimers into multiprotein aggregates. J. Cell Biol. 143:1155-1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marsh, M., and H. T. McMahon. 1999. The structural era of endocytosis. Science 285:215-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meier, O., K. Boucke, S. V. Hammer, S. Keller, R. P. Stidwill, S. Hemmi, and U. F. Greber. 2002. Adenovirus triggers macropinocytosis and endosomal leakage together with its clathrin-mediated uptake. J. Cell Biol. 158:1119-1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mellman, I. 1996. Endocytosis and molecular sorting. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 12:575-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mottershead, D., I. van der Linden, C. H. von Bonsdorff, K. Keinanen, and C. Oker-Blom. 1997. Baculoviral display of the green fluorescent protein and rubella virus envelope proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 238:717-722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mottershead, D. G., K. Alfthan, K. Ojala, K. Takkinen, and C. Oker-Blom. 2000. Baculoviral display of functional scFv and synthetic IgG-binding domains. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 275:84-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O′Reilly, D. R., L. K. Miller, and V. A. Luckow. 1994. Baculovirus expression vectors, a laboratory manual. Oxford University Press, New York, N.Y.

- 39.Ojala, K., D. G. Mottershead, A. Suokko, and C. Oker-Blom. 2001. Specific binding of baculoviruses displaying gp64 fusion proteins to mammalian cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 284:777-784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oker-Blom, C., K. J. Airenne, and R. Grabherr. 2003. Baculovirus display strategies: emerging tools for eukaryotic libraries and gene delivery. Brief. Funct. Genomic. Proteomic. 2:244-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pelkmans, L., and A. Helenius. 2003. Insider information: what viruses tell us about endocytosis. Curr. Opin. in Cell Biol. 15:414-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pieroni, L., D. Maione, and N. La Monica. 2001. In vivo gene transfer in mouse skeletal muscle mediated by baculovirus vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 12:871-881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raty, J. K., K. J. Airenne, A. T. Marttila, V. Marjomaki, V. P. Hytonen, P. Lehtolainen, O. H. Laitinen, A. J. Mahonen, M. S. Kulomaa, and S. Yla-Herttuala. 2004. Enhanced gene delivery by avidin-displaying baculovirus. Mol. Ther. 9:282-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rejman, J., V. Oberle, I. S. Zuhorn, and D. Hoekstra. 2004. Size-dependent internalization of particles via the pathways of clathrin- and caveolae-mediated endocytosis. Biochem. J. 377:159-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Riikonen, R., H. Matilainen, N. Rajala, O. Pentikäinen, M. Johnson, J. Heino, and C. Oker-Blom. 2005. Functional display of an α2 integrin-specific motif (RKK) on the surface of baculovirus particles. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 4:437-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salminen, M., K. J. Airenne, R. Rinnankoski, J. Reimari, O. Valilehto, J. Rinne, S. Suikkanen, S. Kukkonen, S. Yla-Herttuala, M. S. Kulomaa, and M. Vihinen-Ranta. 2005. Improvement in nuclear entry and transgene expression of baculoviruses by disintegration of microtubules in human hepatocytes. J. Virol. 79:2720-2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sarkis, C., C. Serguera, S. Petres, D. Buchet, J. L. Ridet, L. Edelman, and J. Mallet. 2000. Efficient transduction of neural cells in vitro and in vivo by a baculovirus-derived vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:14638-14643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shoji, I., H. Aizaki, H. Tani, K. Ishii, T. Chiba, I. Saito, T. Miyamura, and Y. Matsuura. 1997. Efficient gene transfer into various mammalian cells, including non-hepatic cells, by baculovirus vectors. J. Gen. Virol. 78:2657-2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song, S. U., S. H. Shin, S. K. Kim, G. S. Choi, W. C. Kim, M. H. Lee, S. J. Kim, I. H. Kim, M. S. Choi, Y. J. Hong, and K. H. Lee. 2003. Effective transduction of osteogenic sarcoma cells by a baculovirus vector. J. Gen. Virol. 84:697-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tani, H., C. K. Limn, C. C. Yap, M. Onishi, M. Nozaki, Y. Nishimune, N. Okahashi, Y. Kitagawa, R. Watanabe, R. Mochizuki, K. Moriishi, and Y. Matsuura. 2003. In vitro and in vivo gene delivery by recombinant baculoviruses. J. Virol. 77:9799-9808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tani, H., M. Nishijima, H. Ushijima, T. Miyamura, and Y. Matsuura. 2001. Characterization of cell-surface determinants important for baculovirus infection. Virology 279:343-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Loo, N. D., E. Fortunati, E. Ehlert, M. Rabelink, F. Grosveld, and B. J. Scholte. 2001. Baculovirus infection of nondividing mammalian cells: mechanisms of entry and nuclear transport of capsids. J. Virol. 75:961-970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Volkman, L. E., and P. A. Goldsmith. 1983. In vitro survey of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus interaction with nontarget vertebrate host cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 45:1085-1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Volkman, L. E., and P. A. Goldsmith. 1985. Mechanism of neutralization of budded Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus by a monoclonal antibody: inhibition of entry by adsorptive endocytosis. Virology 143:185-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang, P., D. A. Hammer, and R. R. Granados. 1997. Binding and fusion of Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus to cultured insect cells. J. Gen. Virol. 78:3081-3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wilson, M. E., and K. H. Price. 1988. Association of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus (AcMNPV) with the nuclear matrix. Virology 167:233-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]