Abstract

Thermoplasma acidophilum is sensitive to the antibiotic drug novobiocin, which inhibits DNA gyrase. We characterized DNA gyrases from T. acidophilum strains in vitro. The DNA gyrase from a novobiocin-resistant strain and an engineered mutant were less sensitive to novobiocin. The novobiocin-resistant gyrase genes might serve as T. acidophilum genetic markers.

The members of the domain Archaea are phylogenetically distinct from those of Bacteria and Eukarya (21). Thermoplasma acidophilum is a thermoacidophilic archaeon which was originally isolated from a self-heating coal refuse pile (5). This archaeon grows optimally at pH 1.8 and 56°C, has no cell wall, and is classified as a member of the Euryarchaeota (5). Strains of this archaeon have also been isolated from Japanese hot springs (22). Presently, there are no genetic tools that can be used to manipulate T. acidophilum genomes. A coumarin, novobiocin, competitively inhibits ATP binding to type IIA topoisomerases (3). Novobiocin inhibits T. acidophilum growth (5, 22), and a novobiocin-resistant strain (strain HO-62N1C) has been isolated (22). Therefore, it seems that a novobiocin-resistant DNA gyrase could be used as a genetic marker during the development of transformation methods.

Type II topoisomerases cleave both strands of a DNA duplex and pass a second duplex through the double-stranded break (3). The type II topoisomerases are classified into two types: type IIA, e.g., DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV (TopoIV); and type IIB, e.g., topoisomerase VI (TopoVI). DNA gyrase introduces negative supercoils into closed circular duplex DNA in an ATP-dependent fashion. This supercoiling activity is essential for DNA replication, transcription, and recombination (3). Gyrase also relaxes supercoiled DNA in an ATP-independent manner (14). TopoIV decatenates interlinked daughter chromosomes after DNA replication and can relax positive and negative DNA supercoils (19). TopoVI also has relaxation and decatenation activities (2). In the domain of Archaea, TopoVI is often present and DNA gyrase is occasionally found (6). Only one kind of type II topoisomerase is found in Thermoplasmatales, of which T. acidophilum is a member. Gadelle et al. suggested that the T. acidophilum type II topoisomerase is a DNA gyrase based on its phylogenetic position (6). However, to date, nothing is known about the biochemical characteristics of any archaeal DNA gyrase. Therefore, we have cloned, expressed, purified, and characterized a novobiocin-sensitive T. acidophilum strain and two resistant forms of DNA gyrase.

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

T. acidophilum 122-1B2 was kindly provided by D. G. Searcy. T. acidophilum strains HO-01, HO-54, and HO-121 and the novobiocin-resistant strain HO-62N1C were isolated by Yasuda et al. (22). T. acidophilum culture medium was prepared as described previously (22).

Sequencing the T. acidophilum HO-62N1C gyrase gene.

The archaeal gyrase B sequences were aligned automatically using the program Clustal X, version 1.81 (18), and then optimized manually. Degenerate primers were synthesized based on conserved nucleotide sequences identified using these alignments (Table 1). A partial gyrase B gene sequence was amplified by nested PCR using HO-62N1C genomic DNA. PCR was performed first with the Gyr-1F and Gyr-1R primers and then with the Gyr-2F and Gyr-2R primers. The PCR product was cloned and sequenced.

TABLE 1.

Primers

| Primer name | Sequencea | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Gyr-1F | YTNCCNGGNAARYTNGCNGAYTG | Cloning of the DNA gyrase gene |

| Gyr-1R | GGRTTCATYTCNCCNARNCCYTT | |

| Gyr-2F | GTNGARGGNGANWSNGCNGG | |

| Gyr-2R | CCRTCNACRTCNGCRTCNGTCAT | |

| Lgyr-1F | ACCTGAATCCGAAGAAGCTCAGGTACGGGAA | Inverse PCR |

| Lgyr-2F | TCCGAAGAAGCTCAGGTACGGGAAGATAA | |

| Lgyr-1R | GGCCTGATACTGCCTGTTTCTCGCCTGCT | |

| Lgyr-2R | TACTGCCTGTTTCTCGCCTGCTTGGCCGAT | |

| LgyrA1 | CAGCTCAACGTTCGTTCCTACGA | |

| LgyrA2 | TATGACTGTGTCGATCCTGGCGT | |

| LgyrA4 | CACTGCTTCTCACACGATACGGT | |

| gyrA-EX-F | GGAATTCCATATGGAGAAAAGAGCAGTTGAAGTTG | Construction of expression vectors |

| gyrA-EX-TAR | ATAAAGCTTCACTTTATCACAGCAGCGGC | |

| gyrA-EX-62R | ATAAAGCTTCACTTTATCACCGCAGCAGC | |

| gyrB-EX-F | GGAATTCCATATGACCGAAGACAATTACGACTCT | |

| gyrB-EX-R | GGAATTCCTCAGAGGTCTATGTTCTCAGCATA | |

| TABR136H | CGTAGTATATCTTGCCGTCGTGCTTCACCACTGCTATAAG | Mutation of the gyrase B subunits |

| 62BR136H | CGTAGTATATCTTGCCGTCGTGCTTCACCACGGCTA |

Restriction recognition sites are underlined, and mutated codons are shown in boldface.

A restriction map, flanking the partial gyrase B gene, was constructed using Southern analysis. Based on the physical map, genomic HO-62N1C DNA was digested with either BamHI or SalI, and then the two types of linear fragments were each self-circularized. Inverse PCR was performed using the self-ligated products as templates and using the following primer pairs: L.gyr-1F and L.gyr-2R, L.gyr-2F and L.gyr2R, L.gyr-A1 and L.gyr-A4, or L.gyr-A2 and L.gyr-A4. The PCR products were cloned and sequenced.

Construction of gyrase A and B expression vectors.

The gyrase A (Ta1054) and gyrase B (Ta1055) genes of T. acidophilum 122-1B2 (referred to as gyrATA and gyrBTA hereafter) and the gyrase A and B genes of T. acidophilum HO-62N1C (sequenced as described above and referred to as gyrA62 and gyrB62 hereafter) were amplified from genomic DNA by PCR. The primers used were gyrA-EX-F and gyrA-EX-TAR for gyrATA; gyrA-EX-F and gyrA-EX-62R for gyrA62; and gyrB-EX-F and gyrB-EX-R for gyrBTA and gyrB62. The products were cloned into pCR4-TOPO vectors (Invitrogen, Tokyo, Japan) and sequenced. The gyrase genes were then subcloned into pET-28a(+) at the NdeI and HindIII or EcoRI sites.

A PCR-based mutagenesis technique was used for site-directed mutagenesis of the gyrase B subunit (13). The primers used for the mutagenesis reactions were TABR136H for gyrBTA and 62BR136H for gyrB62. T7P and T7T primers were used as the upstream and downstream primers, respectively. Each PCR product was cloned into a pCR4-TOPO vector and then subcloned into pET-28a(+) at the NdeI and EcoRI sites.

Purification of gyrase A and B subunits.

The recombinant gyrase subunits were individually expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) codon Plus-RIL cells (Stratagene, Tokyo, Japan) or in Rosetta cells (Novagen, Madison, Wisconsin). The cells were grown at 37°C (in 2.5 liters of LB medium with 30 μg/ml kanamycin and 0.5% glucose added). Expression was induced by addition of isopropyl beta-d-thiogalactopyranoside to a final concentration of 1 mM, and then the cultures were incubated for 3 more hours. After expression, E. coli cells were harvested and suspended in ice-cold buffer A that contained 20 mM KPi, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 20% glycerol, 10 mM imidazole, and one tablet of complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Tokyo, Japan) for every 50 ml of buffer. The cells were kept on ice, treated with 1 mg/ml lysozyme for 30 min, and then sonicated. Cell lysates were centrifuged at 82,800 × g for 20 min. The supernatants containing recombinant GyrATA, GyrBTA, GyrA62, or GyrB62 were heat-treated at 60°C for 20 min. Those of GyrB(R136H)TA and GyrB(R136H)62 were also treated for 20 min but at 55°C. The precipitates were removed by centrifugation at 82,800 × g for 20 min. Each subunit was purified by column chromatography. Each supernatant was individually applied to Ni2+-NTA (Amersham Biosciences, Tokyo, Japan) equilibrated with buffer A. The columns were each washed with 3 column volumes of buffer A, and the gyrase subunits were eluted using a gradient of 10 to 300 mM imidazole in buffer A. Fractions that contained a gyrase subunit were combined and dialyzed against buffer B containing 20 mM KPi, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 20% glycerol. The dialyzed samples were each loaded onto 6 ml of ResourceQ (Amersham Biosciences, Tokyo, Japan) equilibrated with buffer B. Each column was washed with 10 column volumes of buffer B. The samples were each eluted with a linear elution gradient of 50 to 400 mM NaCl in buffer B. The sample fractions were combined and concentrated using a Vivaspin I 20-ml concentrator (Vivascience, Hannover, Germany). The gyrase fractions were dialyzed against 20 mM KPi, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 50% glycerol and stored at −80°C.

DNA supercoiling, relaxation, and decatenation assays.

DNA supercoiling activity was assayed by monitoring the conversion of relaxed pBR322 to its supercoiled form (7). Complete reaction mixtures (30 μl) contained 35 mM piperazine-1, 4-bis(2-ethanesulphonic acid), pH 6.5, 0.14 mM Na3-EDTA, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 3 mM spermidine, 0.01% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin, 9.5 μg/ml E. coli tRNA, 1.4 mM ATP, 6 mM MgCl2, 300 ng relaxed pBR322, and 2 units each of the gyrase A and B subunits. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 50°C. Reactions were terminated by addition of 30 μl phenol-chloroform. Twenty microliters of each reaction mixture was mixed with 2 μl of loading buffer (1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 50% glycerol, and 0.05% bromophenol blue) and then electrophoresed in a 0.8% agarose gel (135 by 135 by 10 mm) equilibrated with Tris-borate-EDTA buffer (16). One unit of enzyme activity is defined as the amount of gyrase that converts one-half of the initial 300 ng of relaxed pBR322 to the supercoiled form in 30 min at 50°C. DNA relaxation and decatenation activities were assayed under the same conditions as those for assay supercoiling, except that the substrates were supercoiled pBR322 or kinetoplast DNA, respectively, and the relaxation times and the amounts of enzyme differed. (See the legend of Fig. 3 for additional details.)

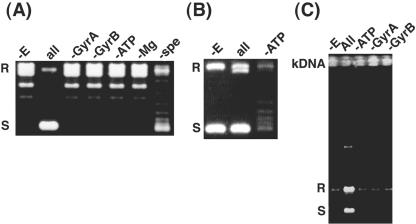

FIG. 3.

Assays of T. acidophilum gyrase activities. (A) Supercoiling activity. Supercoiling was measured in the absence of enzyme (-E); in the presence of all reaction components (all) as described in the text; and in the absence of one of the following components: GyrATA (-GyrA); GyrBTA (-GyrB); ATP (-ATP); Mg2+ (-Mg); or spermidine (-spe). The substrate was relaxed pBR322, and the reaction time was 5 minutes. The labels on the left mark the positions of relaxed (R) and supercoiled (S) pBR322 DNA. (B) Relaxation activity. Relaxation was measured in the absence of enzyme (-E); in the presence of all components, including 10 units each of GyrATA and GyrBTA, and ATP (all); and in the presence of all components except ATP (-ATP). The substrate was supercoiled pBR322, and the reaction time was 2 hours. The labels on the left mark the positions of relaxed (R) and supercoiled (S) pBR322 DNA. (C) Decatenation activity. Decatenation was measured in the absence of enzyme (-E); in the presence of all components including 4 units each of GyrATA and GyrBTA (all); and in the absence of one of the following components: ATP (-ATP); GyrATA (-GyrA); and GyrBTA (-GyrB). The substrate was intertwined kinetoplast DNA, and the reaction time was 30 min. The labels on the left mark the positions of relaxed (R) and supercoiled (S) monomeric kinetoplast DNA.

Effects of novobiocin on the growth of T. acidophilum strains.

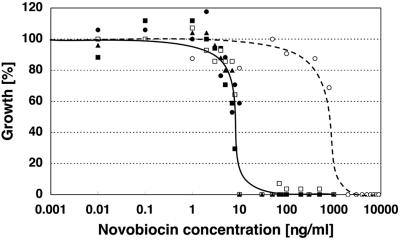

Novobiocin is a potent growth inhibitor of T. acidophilum (5). The novobiocin 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) for the T. acidophilum 122-1B2, HO-01, HO-54, and HO-121 strains are about 0.01 μg/ml (Fig. 1). However, the IC50 for HO-62N1C is 1.0 μg/ml. Therefore, the effect of novobiocin on the growth of HO-62N1C is about 100-fold smaller than it is on the other strains.

FIG. 1.

Effects of novobiocin on growth of T. acidophilum strains. The T. acidophilum strains (filled circles, 122-1B2; filled squares, HO-01; open squares, HO-54; open circles, HO-62N1C; filled triangles, HO-121) were cultured in the present of various concentrations of novobiocin (0 to 10 μg/ml) at 56°C. Cell growth after 75 h was estimated using the absorbance of the culture at 600 nm. Growth in the absence of novobiocin is defined as 100%. The solid line follows the concentration dependencies for 122-1B2, HO-01, HO-54, and HO-121. The broken line follows the concentration dependence for HO-62N1C.

Cloning and sequencing of the T. acidophilum HO-62N1C gyrase genes.

The positions of the gyrase subunit genes have been identified in the genome of T. acidophilum 122-1B2 (15). Novobiocin inhibits ATP binding to type II topoisomerases (1, 8). To determine whether the resistance to novobiocin by HO-62N1C is caused by a decreased binding affinity between the antibiotic and the gyrase, we purified recombinant 122-1B2 and HO-62N1C gyrases and assayed their supercoiling activities.

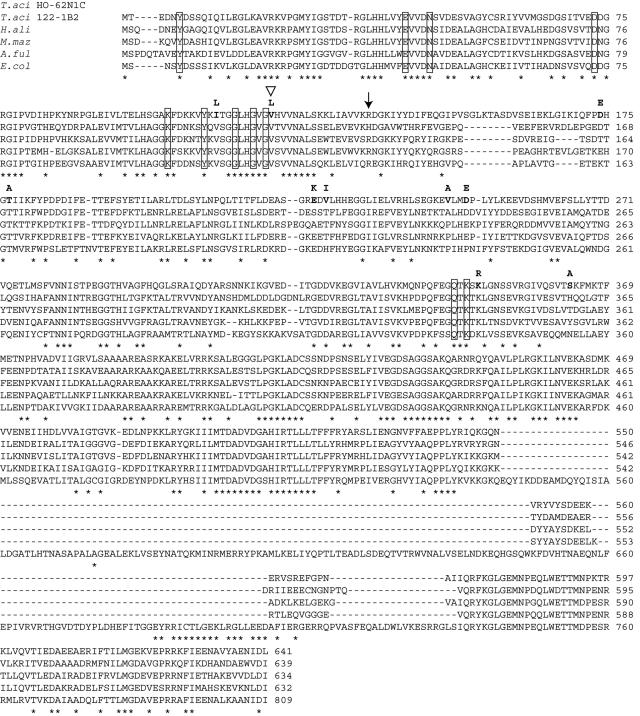

A comparison of the 122-1B2 and HO-62N1C sequences shows that the number of mutated amino acid residues is 8 for the A subunit and 10 for the B subunit (Fig. 2). A R136H mutation in the ATP-binding site of the E. coli gyrase B subunit causes novobiocin resistance, as does a R138H mutation in the “Haloferax alicantei” B subunit (9, 10). However, the corresponding amino acid sequences are the same for the ATP-binding regions of the B subunits of 122-1B2 and HO-62N1C. The spontaneous mutation S127L, which is present in the Streptococcus pneumoniae gyrase B subunit, also causes novobiocin resistance (11). GyrBTA has a valine and GyrB62 has a leucine at the corresponding position (residue 119) (Fig. 2). Accordingly, the mutation at position 119 may be responsible for the increased novobiocin resistance found for HO-62N1C. However, site-directed mutagenesis is needed to validate this proposal.

FIG. 2.

Gyrase B subunit sequence alignments. ATP-binding sites are boxed (20). Asterisks indicate conserved residues. Amino acids of HO-62N1C that are different from those of 122-1B2 are shown in bold type above the HO-122-1B2 sequence. Accession numbers for the sequences are as follows: T. acidophilum (T.aci) 122-1B2, CAC12183; “H. alicantei” (H.ali), A39135; Methanosarcina mazei (M.maz), AAM32115; Archaeoglobus fulgidus (A.ful), O29720; and E. coli (E.col), BAA20341. An arrow indicates the mutation site in the novobiocin-resistant gyrase B genes of E. coli and “H. alicantei” (4, 10). An open triangle indicates the mutation site in the Streptococcus pneumoniae gene (11).

Construction of expression vectors for T. acidophilum DNA gyrase and purification of recombinant His-tagged GyrATA, GyrBTA, GyrA62, and GyrB62.

For expression of the archaeal gyrases, all genes were first PCR amplified and then cloned into pET-28A(+), which is a T7 promoter-based expression vector. Hexahistidine tags were fused to the N termini of all expressed subunits. The recombinant gyrase subunits of T. acidophilum 122-1B2 (GyrATA and GyrBTA) and GyrA62 were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) codon Plus-RIL cells, while GyrB62 was expressed in E. coli Rosetta cells. All expressed subunits were purified using heat treatment, Ni-chelating chromatography, and ion-exchange chromatography. From approximately 1 gram of wet E. coli cells, 0.9 to 1.6 mg of soluble protein was purified, with the exception of GyrB62, for which 0.3 mg was purified (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Purification of DNA gyrase

| Strain | Subunit | Wet wt of cells (g) | Amt of purified protein (mg) | Sp act (U/mg)a | IC50 (μg/ml)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TA | GyrA | 4.3 | 5 | 5 × 104 | |

| GyrB | 7.3 | 8.1 | 3.5 × 104 | 0.57 | |

| GyrBR136H | 12.2 | 20 | 1 × 104 | 1.6 | |

| HO-62N1C | GyrA | 9.9 | 9 | 5 × 104 | |

| GyrB | 15.0 | 4.3 | 3.5 × 104 | 28 | |

| GyrBR136H | 10.9 | 17 | 2 × 104 | 130 |

The definition of a unit of activity is given in Materials and methods. The activity of each subunit was estimated in the presence of an excess amount of the other subunit. When GyrB activity was assayed, 15 units of GyrA were present. When GyrA activity was assayed, 10.5 units of GyrB were present.

The novobiocin concentration that inhibits supercoiling activity by 50%, as calculated using the data of Fig. 4.

Gyrase supercoiling, relaxation, and decatenation activities.

The supercoiling activity of DNA gyrase requires a divalent cation, such as Mg2+, and is stimulated by spermidine (14). We found that the supercoiling activity of the T. acidophilum gyrase also required ATP and Mg2+ and was stimulated by spermidine when assayed with relaxed pBR322 DNA (Fig. 3A). Both A and B subunits are required for supercoiling. The optimal pH is 6.5, which is near the internal pH of T. acidophilum (17), and the optimal concentrations of Mg2+ and spermidine are 2 to 10 and 3 mM, respectively (data not shown).

Gyrases usually catalyze the relaxation of supercoiled DNA given the same conditions as used for supercoiling, except that ATP is not necessary; however, the relaxation reaction is about 20 to 40 times less efficient than supercoiling (14). We found that, within 2 hours, relaxation of negatively supercoiled DNA by 10 units of gyrase was detectable and that relaxation did not require ATP (Fig. 3B). ATP-dependent decatenation activity was also detected when assayed with kinetoplast DNA (Fig. 3C). Therefore, the activities of the archaeal gyrase are similar to those of bacterial gyrases (14).

These results and the absence of a TopoVI-like gene in the T. acidophilum genome support the possibility that the gyrases of thermoplasmatales perform several functions, including decatenation (6). Alternatively, the Thermoplasmatales TopoIIIs, e.g., Ta0063 of T. acidophilum, may be responsible for decatenation of daughter chromosomes; the E. coli TopoIII has decatenation activity (12). However, to date, it has not been shown that any archaeal TopoIII has decatenation activity. Assigning an archaeal decatenation activity to one or more enzymes is an area open to investigation.

Inhibition of gyrase DNA supercoiling activity by novobiocin.

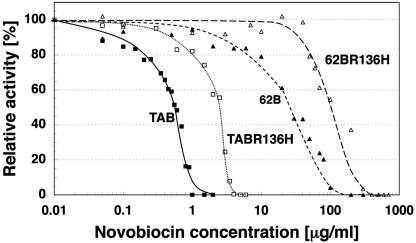

To determine whether the affinity of GyrB62 towards novobiocin is less than that of GyrBTA, we tested the effect of novobiocin on the supercoiling abilities of the wild-type gyrase and a gyrase composed of GyrATA and GyrB62 (Fig. 4). Because GyrATA was present in both holoenzymes and because the reactions contained the same number of subunits (expressed as units of gyrase activity), any differences in novobiocin sensitivity could be attributed to GyrB62. The IC50, which is the drug concentration that inhibits supercoiling by 50%, is 0.57 μg/ml for the wild-type gyrase and 28 μg/ml for the gyrase containing GyrB62 (Fig. 4 and Table 2). Therefore, an increase in novobiocin resistance can be attributed to a mutation in GyrB62.

FIG. 4.

Concentration-dependent inhibition of supercoiling activity by novobiocin. The relative supercoiling activity is reported as the extent to which fully supercoiled pBR322 accumulated in 30 minutes. Reactions were performed using GyrATA and GyrBTA (TAB; closed squares); GyrATA and GyrB(R136H)TA (TABR136H; open squares); GyrATA and GyrB62 (62B; closed triangles); or GyrATA and GyrB(R136H)62 (62BR136H; open triangles) with varying amounts of novobiocin present. Four units of each subunit was used. A value of 0% relative activity is not indicative of a complete lack of activity because only DNA molecules that were supercoiled to the maximum extent were measured when calculating the relative activity.

If a novobiocin-resistant gyrase is to be a reliable genetic marker, then spontaneous novobiocin-resistant mutations arising in the host cell gyrB gene must not be allowed to produce false positives during transformation assays. Introduction of a second novobiocin-resistant mutation that further increases the level of antibiotic resistance would diminish the possibility that false positives would be selected. An R136H mutation in the B subunit of the E. coli gyrase increases the novobiocin IC50 10-fold (4). We engineered this mutation into the genes for GyrBTA and GyrB62, and the resulting proteins are named, respectively, GyrB(R136H)TA and GyrB(R136H)62 (Fig. 2). The specific activities of both mutants are less than that of the wild-type archaeal gyrase, which is a phenomenon also found for the E. coli gyrase mutant (Table 2) (4). When the R136H mutation is present in GyrB(R136H)TA, the resistance to novobiocin is 2.8-fold greater than that found for the wild-type gyrase, and when the mutation is present in GyrB(R136H)62, the resistance is 4.6-fold greater than that found for the gyrase containing GyrB62.

GyrB(R136H)62 has the greatest resistance to novobiocin. The GyrB(R136H)62 gene may prove to be a useful selectable marker during T. acidophilum genetic studies. We have identified a plasmid in T. acidophilum (22). This plasmid, with the gene for GyrB(R136H)62 inserted, should allow us to develop a transformation method for T. acidophilum.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the gyrase gene from HO-62N1C has been deposited into the DNA Data Bank of Japan and is identified by the accession number AB206999.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Project on Protein Structural and Functional Analyses from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bellon, S., J. D. Parsons, Y. Wei, K. Hayakawa, L. L. Swenson, P. S. Charifson, J. A. Lippke, R. Aldape, and C. H. Gross. 2004. Crystal structures of Escherichia coli topoisomerase IV ParE subunit (24 and 43 kilodaltons): a single residue dictates differences in novobiocin potency against topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1856-1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergerat, A., D. Gadelle, and P. Forterre. 1994. Purification of a DNA topoisomerase II from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus shibatae. A thermostable enzyme with both bacterial and eucaryal features. J. Biol. Chem. 269:27663-27669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Champoux, J. J. 2001. DNA topoisomerases: structure, function, and mechanism. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70:369-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Contreras, A., and A. Maxwell. 1992. gyrB mutations which confer coumarin resistance also affect DNA supercoiling and ATP hydrolysis by Escherichia coli DNA gyrase. Mol. Microbiol. 6:1617-1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darland, G., T. D. Brock, W. Samsonoff, and S. F. Conti. 1970. A thermophilic, acidophilic mycoplasma isolated from a coal refuse pile. Science 170:1416-1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gadelle, D., J. Filee, C. Buhler, and P. Forterre. 2003. Phylogenomics of type II DNA topoisomerases. Bioessays 25:232-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gellert, M., K. Mizuuchi, M. H. O'Dea, and H. A. Nash. 1976. DNA gyrase: an enzyme that introduces superhelical turns into DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 73:3872-3876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gellert, M., M. H. O'Dea, T. Itoh, and J. Tomizawa. 1976. Novobiocin and coumermycin inhibit DNA supercoiling catalyzed by DNA gyrase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 73:4474-4478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holdgate, G. A., A. Tunnicliffe, W. H. J. Ward, S. A. Weston, G. Rosenbrock, P. T. Barth, I. W. F. Taylor, R. A. Pauptit, and D. Timms. 1977. The entropic penalty of ordered water accounts for weaker binding of the antibiotic novobiocin to a resistant mutant of DNA gyrase: a thermodynamic and crystallographic study. Biochemistry 36:9663-9673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmes, M. L., and M. L. Dyall-Smith. 1991. Mutations in DNA gyrase result in novobiocin resistance in halophilic archaebacteria. J. Bacteriol. 173:642-648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munoz, R., M. Bustamante, and A. G. de la Campa. 1995. Ser-127-to-Leu substitution in the DNA gyrase B subunit of Streptococcus pneumoniae is implicated in novobiocin resistance. J. Bacteriol. 177:4166-4170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nurse, P., C. Levine, H. Hassing, and K. J. Marians. 2003. Topoisomerase III can serve as the cellular decatenase in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 278:8653-8660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Picard, V., and S. C. Bock. 1997. Rapid and efficient one-tube PCR-based mutagenesis method. Methods Mol. Biol. 67:183-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reece, R. J., and A. Maxwell. 1991. DNA gyrase: structure and function. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 26:335-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruepp, A., W. Graml, M. L. Santos-Martinez, K. K. Koretke, C. Volker, H. W. Mewes, D. Frishman, S. Stocker, A. N. Lupas, and W. Baumeister. 2000. The genome sequence of the thermoacidophilic scavenger Thermoplasma acidophilum. Nature 407:508-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 17.Searcy, D. G. 1976. Thermoplasma acidophilum: intracellular pH and potassium concentration. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 451:278-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson, J. D., T. J. Gibson, F. Plewniak, F. Jeanmougin, and D. G. Higgins. 1997. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:4876-4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ullsperger, C., and N. R. Cozzarelli. 1996. Contrasting enzymatic activities of topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 271:31549-31555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wigley, D. B., G. J. Davies, E. J. Dodson, A. Maxwell, and G. Dodson. 1991. Crystal structure of an N-terminal fragment of the DNA gyrase B protein. Nature 351:624-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woese, C. R., O. Kandler, and M. L. Wheelis. 1990. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:4576-4579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yasuda, M., A. Yamagishi, and T. Oshima. 1995. The plasmids found in isolates of the acidothermophilic archaebacterium Thermoplasma acidophilum. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 128:157-162. [Google Scholar]