Abstract

Despite recent declines in overall sexual activity, sexual risk-taking remains a substantial danger to US youth. Existing research points to athletic participation as a promising venue for reducing these risks. Linear regressions and multiple analyses of covariance were performed on a longitudinal sample of nearly 600 Western New York adolescents in order to examine gender- and race-specific relationships between “jock” identity and adolescent sexual risk-taking, including age of sexual onset, past-year and lifetime frequency of sexual intercourse, and number of sexual partners. After controlling for age, race, socioeconomic status, and family cohesion, male jocks reported more frequent dating than nonjocks but female jocks did not. For both genders, athletic activity was associated with lower levels of sexual risk-taking; however, jock identity was associated with higher levels of sexual risk-taking, particularly among African American adolescents. Future research should distinguish between subjective and objective dimensions of athletic involvement as factors in adolescent sexual risk.

Keywords: jock identity, athletic activity, sexual risk, adolescent, gender, race

Despite declines in overall adolescent sexual activity over the past decade (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2002; Santelli et al., 2000), sexual risk-taking (e.g., multiple partners, sexual precocity, unprotected intercourse) remains a substantial danger to US youth. Each year, American adolescents experience nearly a million unintended pregnancies and more than 4 times that many new cases of sexually transmitted diseases (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2000). Strategies to reduce sexual risk have commonly employed narrowly focused approaches such as contraceptive distribution, sex education, and abstinence programs (Franklin et al., 1997). In their search for interventions that reduce sexual risk-taking, some researchers and policy-makers have begun to cast a wider net that addresses the larger social and developmental contexts of adolescents’ daily lives, including routine behaviors for which the linkage to sexual risk outcomes is indirect (Kirby, 1997; Males, 1993). Adolescent athletic involvement constitutes one such area of interest. The present study examined the gender- and race-specific relationships among two distinct dimensions of athletic involvement (specifically, frequency of athletic activity and “jock” identity), dating, and sexual risk-taking in one longitudinal sample of Western New York adolescents.

SPORTS AND ADOLESCENT SEXUAL RISK

Recent research has identified adolescent athletic participation as a promising avenue for promoting sexually responsible behavior, particularly among girls. Female athletes at the high school and college levels report less frequent and less risky sexual activity than nonathletes (Kokotailo et al., 1998; Miller et al., 1998b, 1999b; Sabo et al., 1998, 1999; Savage and Holcomb, 1999). Female high school sports participation has also been linked with reduced odds of teen pregnancy (Page et al., 1998; Rome et al., 1998; Zill et al., 1995). These findings have led the Women’s Sports Foundation and other organizations to advocate for adolescent athletic participation as a preventive strategy against unwanted teen pregnancy, sexually transmitted disease, and other undesirable concomitants of early and high-risk sexual activity (Sabo et al., 1998).

Less attention has been devoted to the effects of sports participation on male adolescent sexual risk-taking; and the results of the few studies available have been inconsistent. Some have found male athletes to be at greater risk for recent sexual activity (Miller et al., 1999b) or involvement in a pregnancy (Zill et al., 1995). Others have found no significant association between male athletic participation and frequency of intercourse (Miller et al., 1998b; Sabo et al., 1999), contraction of a sexually transmitted disease (Page et al., 1998), or involvement in a pregnancy (Page et al., 1998; Sabo et al., 1999). These apparent inconsistencies may be due in part to racial differences in the relationship between sports participation and male adolescent sexual behavior; both Miller et al. 2002 and Pate et al. 2000 reported lowered odds of sexual risk for White boys but heightened odds for African American boys.

Cultural resource theory (Miller et al., 1998b) examines how sports participation affects the interaction of gender-specific cultural scripts and bargaining resources in the negotiation of sexual outcomes. This theory suggests that, in the context of sexual decision-making, the adolescent draws on both (a) cultural expectations or scripts regarding gender-appropriate sexual behavior, and (b) a range of personal and social resources that may be used to bring about desired outcomes in a potentially sexual encounter. Athletic participation provides both girls and boys with additional resources to use in this bargaining process, but its relationship to cultural scripts or expectations differs substantially across gender lines. Since sport has traditionally been steeped in the mythos of masculinity, participation should reinforce boys’ commitment to the traditional gender script that validates sexual risk, aggressiveness, and promiscuity. Conversely, sport exposes female athletes to a subculture antithetical to conventional passive femininity, weakening their adherence to the traditional script which encourages women to define themselves as adjuncts to male status and male desire.

Gender and Racial Variations

Extant research indicates that the effects of athletic participation on sexual behavior clearly differ by gender; while female athletes report lower levels of sexual activity than their nonathletic counterparts, male athletes are somewhat more sexually active than male nonathletes. It is also well known that the timing, rates and unintended outcomes of sexual activity are race- and ethnicity-specific (Coley and Chase-Lansdale, 1998; Furstenberg et al., 1987; Newcomer and Baldwin, 1992), although those differences stem at least in part from other factors closely correlated with race, such as income or family structure (Lauritsen, 1994). A growing body of research has examined whether these patterns can be predicted in uniform ways by athletic participation. While female athletes and White male athletes report less high-risk sexual behavior than nonathletes, risk-taking may actually be elevated in African American male athletes (Miller et al., 1999a; Pate et al., 2000). Miller et al. 2002 found that athletic participation was associated with significantly lower odds of sexual risk-taking among non Hispanic White adolescent girls and boys, and with significantly higher odds of sexual risk-taking among nonHispanic African American adolescent boys. Being an athlete did not significantly buffer Hispanic or Asian/Pacific Islander adolescents of either gender against sexual risk. Erkut and Tracy (2000) also noted a negative association between athletic participation and the co-occurrence of drug use and sexual activity for African American adolescent girls but not for their White peers.

Cultural resource theory suggests that racial/ethnic variations in the relationship between sports participation and adolescent sexual risk stem from two sources. First, if we posit that opportunities for acquiring alternative, nonathletic resources are unequally distributed by race, then the theory suggests that sport may constitute a more salient resource in the social landscape of African American teens than White teens. Second, if athletic involvement reinforces commitment to conventionally masculine scripts but weakens commitment to conventionally feminine scripts, then the impact of sports participation may depend on the extent to which adolescents are committed to those scripts to begin with. In particular, African American female adolescents may be less tied to traditional gender norms than their nonAfrican American counterparts. Using the Adolescent Femininity Ideology Scale, Tolman and Porche (2000) found that African American girls were significantly more resistant to the constraints of hegemonic femininity than White girls. In relative terms, since they may be less likely to perceive athleticism in gender-transgressive terms, sports participation may be less empowering or liberating for African American girls and thus have less impact on sexual risk behavior than for White girls.

Jock Identity Vs. Athletic Participation

Past research indicates an association between sports participation and sexual risk-taking, but the underlying mechanisms are far from clear. What is it about the lived athletic experience that influences the ways in which teens conduct their sexual relationships? On one hand, athletic participation is a social activity; it requires, to some degree, enmeshment in an organized social network of peers and supervisory adults who reinforce conventional norms and values. Most extant research on the connection between athleticism and sexual risk-taking has focused on athletic participation in this objective sense, by examining team membership or frequency of athletic activity. On the other hand, involvement with sports may be more subjective or internal, via the development of an athletic or “jock” identity (public and private identification with the athletic role).6 The relationships among athletic activity, jock identity, and sexual risk-taking are further complicated by the fact that each of the components is subject to variation by both gender and race.

No extant research on the linkage between sports and sexual risk has disaggregated jock identity and athletic participation as separate constructs. Analyses of this relationship tend to hinge on team membership or frequency of sports activity rather than on teens’ perceptions of themselves. However, the classification of adolescents as athletes or nonathletes based on their participation in formal sports programs may obscure the strength and exclusivity of their identification with that role. Not all teens with a strong jock identity join sports teams, and not all team members consider their athletic status a particularly salient source of personal identity (Lantz and Schroeder, 1999).

One way to understand sport-related identity is to situate it within the context of peer interaction. For example, Brown and colleagues have constructed a developmental model of peer group affiliation that locates adolescents within a complex network of social crowds (e.g., druggies/burnouts, brains, preppies, nerds) that are both relational and reputational in nature (Brown et al., 1986; Brown et al., 1994). Although the constellation of crowds varies somewhat, virtually all extant models of adolescent crowd affiliation have prominently featured the “jock” crowd, sometimes in isolation and sometimes as part of a larger elite or “popular” group.

A number of researchers have examined the typical health-risk behaviors of members of various crowds (e.g., Hussong, 2002; Miller et al., 2003; Sussman et al., 1990). Dolcini and Adler (1994) found that “elites” (a crowd that subsumed both popular and athletic teens) were significantly more likely to have had sexual intercourse than their peers. La Greca et al. 2001 found that, compared to most other peer crowds, jocks scored high on measures of sexual risk (casual sex, unprotected sex, and multiple sex partners) and fairly high on measures of risk-taking in general. However, the researchers’ focus on comparisons between specific peer crowds precluded in-depth assessment of the nature of the relationship between jock identity and sexual risk-taking. Moreover, no study of jock identity to date has addressed the distinction between the subjective and objective dimensions of athletic involvement. In the present study, we sought to ascertain the relative nature and importance of these two dimensions in understanding adolescent sexual risk. In addition, given the clearly gender-specific and race-specific nature of the relationships between objective athletic participation and sexual risk, we were interested to know if these distinctions held for subjective jock identity as well. If the correspondence between athletic participation and jock identity is strong, as may reasonably be expected, then the logic of cultural resource theory should apply not only to adolescents’ sports-oriented behavior but to their sports-oriented identity as well.

Dating

Cultural resource theory takes explicit note of the gendered scripts upon which adolescents draw when negotiating potential heterosexual relationships. Traditionally, these behavioral prescriptions encouraged opportunistic sexual risk-taking and/or predation in men while instructing women to treat sexual access as a bargaining chip in negotiating relationships with others (Gagnon and Simon, 1973; Laws and Schwartz, 1977; Oliver and Hyde, 1993). Such oppositional scripts may appear quaint or even obsolete in contemporary parlance. However, there is some evidence to suggest that their influence lingers, such as the finding that men are more likely to emphasize physical gratification as a motive for sex while women are more likely to emphasize intimacy as a motive (Carroll et al., 1985; Cooper et al., 1998; DeLamater, 1987; Simon and Gagnon, 1986). This distinction is particularly likely to be true of adolescents, who often lack extensive repertoires of accumulated experience within which to contextualize their choices regarding sexual activity. According to a survey commissioned by a popular teen magazine as recently as the mid-1990s, most adolescents (76% of girls and 58% of boys) reported that the “most common reason” girls have sex is that their boyfriends want them to (EDK Associates, 1996).

We have thus far speculated that athletic involvement reduces adolescent girls’ sexual risk in part by weakening their adherence to a cultural script which disposes them to perceive their own value in terms of heterosexual attractiveness (Miller et al., 1998b, 1999b). According to cultural resource theory, as female athletes redefine their bodies in terms of physical competence rather than objectified sexual appeal, they are presumably less likely to use sexual risk-taking as a negotiating tool in building relationships with boys and achieving status with peers. The evidence suggests that athletic participation is a source of social status not only for boys, as has traditionally been the case, but increasingly for high school girls as well (Holland and Andre, 1994; Kane, 1988; Suitor and Carter, 1999; Suitor and Reavis, 1995). Cultural resource theory further suggests that girls, upon whom the negative consequences of risk-taking are disproportionately likely to fall, draw upon these enhanced resources to insist upon safer sexual practices (e.g., consistent contraceptive use) than their partners might otherwise prefer.

However, one commonly raised objection to the premises of cultural resource theory contests the presumed voluntary nature of female athletes’ reduced sexual risk-taking. Specifically, it has been suggested that, despite the growing popularity of girls’ and women’s sports in contemporary society, the traditional stigmatization of female jocks as unnatural, overly masculine, and presumptively lesbian may yet linger, causing them to be viewed as less desirable by prospective male sex partners (Blinde and Taub, 1994; Dodge and Jaccard, 2002). If this is the case, then regardless of their overall popularity, girls who are perceived as affiliated with sports may actually be less sought after as dating and/or prospective sex partners. In other words, the buffering effect of sports on female sexual activity may be attributable to lower sexual demand for female athletes. In fact, several studies have documented that female athletes in “sex-inappropriate” sports (e.g., involving body contact and/or physical domination of opponents) are significantly less likely than those in “sex-appropriate” sports to be identified as desirable dating partners by their male contemporaries (Holland and Andre, 1994; Kane, 1988).

However, the supposition that residual stigmatization reduces female athletes’ overall popularity as dating or sex partners has not been directly tested. Dodge and Jaccard (2002) controlled for “involvement in a romantic relationship” as a moderator of the relationship between female sports participation and sexual risk and found that current romantic involvement with a boy was significantly associated with sexual risk-taking but not athletic participation. We suggest that frequency of dating behavior is a better indicator of the dynamic outlined above than romantic involvement, since adolescents may date widely without committing to a specific romantic relationship per se.7 Thornton (1990) documented associations among early initiation of dating, dating frequency, number of sex partners, and permissive attitudes toward premarital sex. While risk-taking can occur outside the dating context, more frequent dating is likely to provide more structured opportunities for sexual encounters.

Because decisions to date are a product of both choice and opportunity, an individual’s popularity level is likely to affect dating frequency. Male jocks, whose athletic prowess has traditionally served as a source of status and bargaining power, should be more likely to both date frequently and take sexual risks. For girls, however, there are several possibilities. If girls are sexually stigmatized by their involvement with sports, then female jocks may be less likely to date, and thus have fewer opportunities to take sexual risks. Conversely, if the status girls gain from athletic participation is translatable into popularity and sexual bargaining power, then female jocks should be more likely to date as nonjocks, but less likely to take sexual risks. In the present analysis, we have hypothesized that these two effects—enhanced popularity, coupled with some degree of residual stigma—cancel each other out, so that dating frequency does not appreciably differ between female jocks and their nonjock counterparts.

The only previous study of adolescent athleticism and romantic relationship involvement examined athletic participation rather than jock identity (Dodge and Jaccard, 2002). Though these two constructs overlap, they are not identical in nature or in their implications for dating and sexual risk behavior. In the following analysis, therefore, we control for the frequency of athletic activity when testing for relationships among jock identity, gender, and dating.

Other Predictors

As previously noted, the interactions of athletic involvement, dating, and sexual risk-taking take place within a social context in which gender and race make a difference. For example, adolescent risk-takers are disproportionately likely to be male and/or African American (Furstenberg et al., 1987; Lauritsen, 1994; Miller and Moore, 1990). Nor is involvement with sports randomly distributed; White males in particular are overrepresented among adolescent athletic participants (Dodge and Jaccard, 2002; Miller et al., 2002). However, although the primary focus of this study is on the gender- and race-specific nexus of jock identity and dating, several other factors have been documented to predict adolescent sexual risk-taking and should also be taken into account. Autonomy grows and accompanying opportunities for sexual experimentation become more common as adolescents get older; unsurprisingly, then, age is significantly associated with sexual activity and risk-taking (Benda and DiBlasio, 1994; Harvey and Spigner, 1995; Miller et al., 1997, 1999b, 2002). Risk-takers are also disproportionately likely to be economically disadvantaged (Harvey and Spigner, 1995; Males, 1993; Miller and Moore, 1990).

Furthermore, the quality of family relationships, particularly children’s relationships with their parents, is demonstrably associated with adolescent sexual behavior. For example, moderate levels of parental strictness (White and White, 1991) and high levels of parental support and monitoring (Barnes and Farrell, 1992; Benda and DiBlasio, 1994) have been linked with lower rates of sexual activity. Miller et al. 1998b found a particularly strong and consistent relationship with family cohesion; specifically, higher levels of family cohesion have been associated with adolescent reports of less frequent sexual activity, fewer sex partners, and later age of coital onset (Miller et al., 1998b).

The present study used a longitudinal sample of nearly 600 Western New York adolescents to examine relationships among “jock” identity, gender, race, and adolescent sexual risk, controlling for age, socioeconomic status, family cohesion, dating behavior, and athletic activity. We hypothesized that both gender and race would condition the relationship between jock identity and adolescent sexual risk-taking. We also examined the argument that female jocks experience lower levels of sexual risk because they are less sought after dating partners and thus have fewer risk-taking opportunities.

HYPOTHESES

In the following analysis, we examine the relationships among jock identity, gender, race, and 4 measures of adolescent sexual risk, while controlling for age, socioeconomic status, family cohesion, dating behavior, and athletic activity. Using a longitudinal sample of over 600 Western New York adolescents, we test 3 hypotheses.

First, we anticipate that gender will interact with jock identity in predicting how often adolescents date. Because sports enhance social status for both boys and girls, but may also carry a residual stigma for the girls that cancels out the social advantage of being a jock, we hypothesize that

H1: Male jocks will date more often than male nonjocks, whereas female jocks will not differ from female non-jocks in their dating frequency.

Second, we anticipate that gender will interact with jock identity in predicting sexual risk behavior. Cultural resource theory suggests that athletic involvement reinforces a sexually aggressive masculine script for boys, while weakening girls’ adherence to a sexually accommodating and passive feminine script. Thus we hypothesize that

H2: Male jocks will engage in more sexual risk-taking than male nonjocks, whereas female jocks will engage in less sexual risk-taking than female nonjocks.

Third, we anticipate that race will interact with jock identity in predicting sexual risk behavior. Because sport is likely to constitute a more salient resource for adolescents of color than for their White counterparts, we hypothesize that

H3: African American jocks will engage in more sexual risk-taking than African American nonjocks, whereas White jocks will engage in less sexual risk-taking than White nonjocks.

METHODS

Data

This analysis is based upon the 6-wave Family and Adolescent Study. Random-digit-dial procedures were used on a computer-assisted telephone network to obtain a regionally representative Western New York sample of 699 households containing at least 1 adolescent aged 12–17 years and at least 1 biological or surrogate parent at wave 1. African American families were oversampled to facilitate hypothesis testing of racial differences (N = 211). Trained interviewers conducted face-to-face interviews in respondents’ homes. Questions about sensitive issues such as sexual risk-taking were reported in private via a self-administered questionnaire. Characteristics of the overall sample at wave 1 closely matched the census distributions in the area (Barnes et al., 1991); that is, respondents were normally distributed by age and gender, with substantial racial differences in SES (e.g., average household income of $38,000 for Whites and $21,000 for African Americans) and in family structure (e.g., 25% single-parent families among Whites and 52% single-parent families among African Americans). Stringent follow-up procedures yielded an initial response rate of 71 percent overall and 77% for African American families, with retention rates of over 90% in subsequent years (see Barnes et al., 1997, 2000 for detailed sampling procedures and sample characteristics). The present analysis uses data from waves 1 and 3, which were approximately 2 years apart. Jock identity was measured at wave 1 (mean age = 14.5 years). Dependent measures and control measures are taken from wave 3 of the data, which included 598 African American or White adolescent subjects (mean age = 16.6 years).

Dependent Measures

In order to capture a more nuanced picture of adolescent sexual risk than would be possible with a single outcome measure, 4 self-report measures of sexual risk were chosen for analysis: overall lifetime number of sex partners, lifetime frequency of sexual intercourse, frequency of intercourse in the past 12 months, and age of first sexual intercourse. Respondents were asked how many different people they had had sexual intercourse with in their lives, with response categories of (0) none, (1) 1, (2) 2 or 3, and (3) 4 or more. For both lifetime and recent (past 12 months) sexual experience, reported frequency of intercourse was divided into 6 categories: (1) never, (2) once, (3) 2 or 3 times, (4) 4 or 5 times, (5) 6–9 times, and (6) 10 or more times. On the basis of preliminary evaluation of the distribution of our sample, we categorized respondents’ age at first intercourse as (1) never, respondent had never had sexual relations; (2) age 15 or older; and (3) age 14 or younger. These 4 measures of sexual risk were closely related to each other, with bivariate correlations ranging from 0.67 to 0.94.

Independent Measures

In order to correct for potential selection effects that might result from the nonrandom distributions of both jock identity and sexual risk-taking across adolescent populations, 4 sociodemographic variables were included in the analysis as controls: gender, age, race, and socioeconomic status. At wave 1, respondents ranged in age from 12 to 17. Because too few (n = 13) Latino, Asian, or Native American respondents were surveyed to permit meaningful analysis, these cases were eliminated from the sample and race was coded into 2 categories: African American and White. African American respondents made up 30% of the unweighted sample; after weighting, they constituted 14%.

To measure family socioeconomic status, we employed 3 measures: family income, mother’s highest level of educational attainment, and father’s highest level of educational attainment. Family income was reported by the adolescent’s parents; where the father was unavailable, the mother provided an estimate of his income. Family income categories included (1) $0–$14,999; (2) $15,000–$34,999; (3) $35,000–$49,999; and (4) $50,000+. Parental education categories included (1) 0–11 years; (2) 12 years; (3) 13–15 years; and (4) 16 or more years. In order to derive a comprehensive measure of family socioeconomic status, we calculated the mean of these 3 measures, so that SES ranged from a low of 1.00 to a high of 4.00.

To measure family cohesion in the present study, we employed Olson et al., 1985 FACES III scale. Respondents were asked to describe their families with respect to a series of 10 statements, such as “Family members ask each other for help”; “Family members feel closer to other family members than to people outside the family”; “Family members like to spend free time with each other”; “Family members consult other family members on their decisions”; and “Family togetherness is very important.” Response choices ranged on a 5-point Likert scale from (1) almost never to (5) almost always. Alpha reliability of the family cohesion scale was 0.82.

To measure dating frequency, respondents were asked how often they “go out on dates,” with responses including (0) never, (1) a few times a year, (2) once a month, (3) 2 or 3 times a month, (4) about once or twice a week, and (5) 3 or more times a week.

Involvement with sports was measured in 2 ways. First, we measured how much time respondents devoted to athletic pursuits. To approximate the total number of hours adolescents spent in athletic activity during the year prior to the survey, we asked respondents in wave 3 how often they “actively participate in sports, athletics, or exercising (other than during school hours) (include after school team practices, games, etc.)” on the same 6-point continuum used for the dating variable. Categories were converted to midpoint measures and multiplied by a respondent estimate of the average number of hours spent on a typical occasion of athletic activity. Thus, for example, a respondent who reported engaging in athletic activity “2 or 3 times a month” (approximately 24–36 times a year, coded to a midpoint of 30) for an average 3 h per occasion, would be coded as spending 90 h on athletic activity in the past year. Finally, to normalize the distribution of responses, the resultant range was collapsed into 6 categories: (0) didn’t play sports in the past year, (1) 1–25 h, (2) 26–100 h, (3) 101– 200 h, (4) 201– 400 h, and (5) over 400 h. It should be noted that this measure includes both exercise activity and sports participation; thus some teens who routinely engage in strenuous physical activity in a socially isolated setting may be unintentionally aggregated with those who participate in the social network of organized athletic programs. However, for the purposes of this study, we considered this approach preferable to the available alternative, a simple dichotomous measure of school sports participation (“Do you participate in sports at school?”) which would not distinguish among different degrees of involvement.

Second, wave-1 respondents were asked, “Teenagers sometimes characterize one another on the basis of their attitudes toward school, clothes, music, partying, and so forth. Some people give names to these types, such as jocks, preps, air heads, burnouts, and so forth. How well does each type fit you?” Those who responded that the “jock” label fit them “very well” or “somewhat” were coded as having a jock identity; those who responded “a little,” “not at all,” or “never heard of this group” were coded as not having a jock identity. The wave 1 measure was used in order to test the prospective predictive ability of prior jock identity with regard to subsequent sexual risk behavior.

RESULTS

Descriptive Analyses

Despite the growing popularity of women’s sports, jock identity remains disproportionately a male characteristic, with 50% of boys but only 23% of girls reporting that the label “jock” fit them at least somewhat well. This identity was also significantly more prevalent among White (37%) than African American respondents (22%). Males and Whites also engaged in more frequent past-year athletic activity than females and African Americans. Significant gender and race differences emerged in dating patterns, with females and Whites reporting more frequent dating over the course of the past year; however, males and African Americans reported significantly earlier sexual debut, and more sex partners overall, than their female or White counterparts (data not shown in tabular form).

Unsurprisingly, jocks of both genders reported more past-year participation in athletic and other physical activity than nonjocks. Among adolescents reporting 2 or more hours of athletic activity per week, 55% of boys and 33% of girls claimed a jock identity; among those reporting fewer than 2 h of athletic activity per week, only 36% of boys and 15% of girls did. Jock identity and athletic activity were significantly correlated, though the correlation was smaller (0.31) than might be expected. However, comparison of weighted mean scores (unadjusted for the effects of sociodemographic differences) suggests that jock identity is more effective in differentiating the dating and sexual behavior of male adolescents than female adolescents (see Table I). Male jocks reported more frequent dating, earlier sexual debut, more frequent past-year and lifetime sexual activity, and a greater lifetime total number of sex partners than their nonjock male counterparts. None of these behaviors differed significantly between female jocks and female nonjocks.

Table I.

Weighted Means: Adolescent Sexual Risk by Gender and Jock Identity

| Female

|

Male

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonjock ID (n = 250) | Jock ID (n = 74) | F | Nonjock ID (n = 137) | Jock ID (n = 135) | F | |

| Age (14–19 years) | 16.60 | 16.47 | ns | 16.53 | 16.51 | ns |

| African American (0–1) | 0.18 | 0.05 | 7.28** | 0.16 | 0.11 | ns |

| Socioeconomic status: low (1) to high (4) | 2.68 | 2.78 | ns | 2.48 | 2.78 | 10.04** |

| Family cohesion: low (10) to high (50) | 28.94 | 30.99 | ns | 29.29 | 29.80 | ns |

| Frequency of dating activity (0 = never, 5 = 3+ times/week) | 3.10 | 3.15 | ns | 2.32 | 3.25 | 25.67*** |

| Hours of athletic activity, past yr (0 = never, 5 = 400+ h) | 2.00 | 2.90 | 18.13*** | 2.96 | 3.71 | 16.59*** |

| Age first had sex (1 = never; 2 = 15/older; 3 = 14/younger) | 1.78 | 1.85 | ns | 1.87 | 2.14 | 7.99** |

| Frequency sex, past year (0 = never; 5 = 10+ times) | 2.00 | 2.40 | ns | 1.84 | 2.45 | 6.14* |

| Frequency sex, lifetime (0 = never; 5 = 10+ times) | 2.21 | 2.54 | ns | 2.14 | 2.82 | 7.51** |

| Number sex partners, lifetime (0 = none; 3 = 4+ partners) | 1.07 | 1.02 | ns | 1.32 | 1.71 | 7.51** |

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001.

Further breakdown of descriptive statistics for male respondents illuminated race-specific behavioral patterns (see Table II). Among White boys, a jock identity was strongly associated with higher frequencies of both athletic participation and dating activity; weakly associated with earlier sexual onset and a greater number of sex partners; and not significantly associated with the past-year or lifetime frequency of sexual intercourse. Conversely, among African American boys, jock identity did not significantly predict either dating or athletic activity, but was strongly associated with higher levels of sexual risk on all 4 measures of sexual activity. No such clear, race-specific behavioral patterns were found for female respondents.

Table II.

Unweighted Means: Male Adolescent Sexual Risk by Race and Jock Identity

| African American male

|

White male

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonjock ID (n = 46) | Jock ID (n = 31) | F | Nonjock ID (n = 94) | Jock ID (n = 98) | F | |

| Age (14–19 years) | 16.26 | 16.35 | ns | 16.59 | 16.53 | ns |

| Socioeconomic status: low (1) to high (4) | 2.14 | 2.20 | ns | 2.54 | 2.86 | 7.57** |

| Family cohesion: low (10) to high (50) | 30.65 | 27.95 | ns | 29.01 | 30.03 | ns |

| Frequency of dating activity (0 = never, 5 = 3+ times/week) | 2.24 | 2.52 | ns | 2.33 | 3.34 | 21.77*** |

| Hours of athletic activity, past yr (0 = never, 5 = 400+ h) | 3.59 | 3.55 | ns | 2.84 | 3.73 | 17.02*** |

| Age first had sex (1 = never; 2 = 15/older; 3 = 14/younger) | 2.11 | 2.74 | 13.79*** | 1.82 | 2.06 | 4.62* |

| Frequency sex, past year (0 = never; 5 = 10+ times) | 1.82 | 3.27 | 11.67*** | 1.85 | 2.34 | ns |

| Frequency sex, lifetime (0 = never; 5 = 10+ times) | 2.30 | 3.79 | 13.41*** | 2.11 | 2.70 | ns |

| Number sex partners, lifetime (0 = none; 3 = 4+ partners) | 1.63 | 2.52 | 13.54*** | 1.27 | 1.61 | 4.24* |

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001.

Multivariate Analyses

In order to control for important sociodemographic factors, we conducted linear regression analyses to predict adolescent dating frequency, with main effects entered as a first block and the 2-way interaction of gender and jock identity entered as a 2nd block (see Table III). Both athletic activity and jock identity were associated with significantly higher frequency of dating behavior. To probe the significant interaction of gender and jock identity, we also conducted separate, gender-specific analyses (Table III). Controlling for the effects of age, race, socioeconomic status, and family cohesion, dating frequency was predicted by both athletic activity and jock identity for boys but not girls. Specifically, male jocks dated more frequently than male nonjocks; female jocks did not differ significantly from female nonjocks in their dating behavior.

Table III.

Linear Regression Analyses Predicting Adolescent Dating Frequency, by Gender

| Whole sample (N = 589)

|

Females (n = 323)

|

Males (n = 266)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent vars | β | F | R2 | β | F | R2 | β | F | R2 |

| Model 1: Main effects onlya | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.16 | ||||||

| Female | 0.15 | 12.35*** | |||||||

| Age | 0.24 | 36.22*** | 0.27 | 26.88*** | 0.19 | 11.31** | |||

| African American | −0.16 | 14.85*** | −0.25 | 18.64*** | −0.12 | 4.10* | |||

| SES | 0.01 | ns | 0.01 | ns | −0.01 | ns | |||

| Family cohesion | −0.04 | ns | −0.07 | ns | 0.01 | ns | |||

| Hours of athletic activity | 0.13 | 8.56** | 0.01 | ns | 0.24 | 16.36*** | |||

| Jock identity | 0.10 | 5.83* | −0.02 | ns | 0.21 | 13.03*** | |||

| Model 2: Main effects + 2-way interaction | 0.14 | ||||||||

| Female by jock identity | −0.16 | 8.72** | |||||||

Variables in the whole-sample analysis were entered in two additive blocks. The first model included main effects only; the second model included both main effects and product terms. Coefficients reported under “Model 1: Main Effects Only” are from Model 1; the coefficient reported under “Model 2: Main effects + 2-way interaction” is from Model 2.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001.

Because of the strong correlations among the dependent measures of sexual risk (between 0.67 and 0.94), multiple analyses of covariance were used to explore the associations among jock identity, race, gender, and sexual risk-taking, controlling for age, socioeconomic status, family cohesion, dating frequency, and athletic activity. Table IV shows findings for the sample as a whole. Sociodemographic characteristics played the expected role in predicting adolescent sexual risk behavior, with lower levels of risk-taking reported by respondents who were female or younger (3 univariate factors each) and by respondents who were White, higher in socioeconomic status, or higher in family cohesion (all 4 univariate factors). Dating frequency significantly predicted the multivariate risk factor, as well as all of the univariate indicators of sexual risk: the more respondents had dated in the past year, the earlier their age of sexual debut, the more frequently they had had sexual intercourse, and the more sex partners they reported.

Table IV.

Multivariate Analysis of Variance Predicting Adolescent Sexual Risk Behavior (N = 589)

| Multivariate F

|

B

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | 4 Dep vars taken together | Age of onset of intercourse | Frequency of sex, past year | Frequency of sex, lifetime | Number of sex partners, lifetime |

| Model 1: Main effects onlya | |||||

| Female | 13.91*** | −0.28*** | −0.21 | −0.40* | −0.56*** |

| Age | 23.88*** | −0.01 | 0.34*** | 0.36*** | 0.18*** |

| African American | 8.22*** | 0.33*** | 0.41* | 0.55** | 0.49*** |

| SES | 3.94** | −0.15*** | −0.26** | −0.28** | −0.19*** |

| Family cohesion | 5.71*** | −0.01*** | −0.03*** | −0.03** | −0.02*** |

| Frequency of dating | 27.62*** | 0.16*** | 0.47*** | 0.48*** | 0.22*** |

| Hours of athletic activity | 1.96 | −0.05* | −0.09 | −0.12* | −0.05* |

| Jock identity | 4.09** | 0.24*** | 0.60*** | 0.62*** | 0.29** |

| Model 2: 2-way interactionsa | |||||

| Female by African American | ns | −0.10 | 0.44 | 0.07 | −0.11 |

| Female by frequency of dating | ns | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.11 | −0.00 |

| African Am. by frequency of dating | ns | −0.05 | −0.22* | −0.21* | −0.04 |

| Female by athletic activity | ns | −0.07 | −0.16 | −0.12 | −0.10 |

| African Am. by athletic activity | ns | −0.01 | 0.11 | −0.00 | 0.01 |

| Female by jock identity | ns | 0.01 | 0.50 | 0.32 | −0.09 |

| African Am. by jock identity | ns | 0.37* | 1.16** | 1.02* | 0.56* |

Variables were entered in two additive blocks. First, all main effects were entered simultaneously (coefficients reported under the “Main Effects” section); then main effects and two-way interactions were entered simultaneously (two-way interaction coefficients only reported under the “2-Way Interactions” section).

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

As anticipated, the relationship between adolescent sports involvement and sexual risk was contingent on the measure of athletic involvement used. Total hours of athletic activity significantly predicted 3 of the 4 univariate sexual risk factors; more frequent participation in sports, athletics, or exercising was associated with later age of sexual onset, less frequent lifetime sexual activity, and fewer sex partners. Jock identity predicted the multivariate risk factor, but for all 4 univariate factors, the association was positive, even after controlling for total hours of athletic activity. Jocks reported more extensive sexual histories than nonjocks; that is, they initiated sexual activity at a younger age, had sexual intercourse more frequently on both time scales (past-year and lifetime), and had a greater number of sex partners.

In order to dissect the gender- and race-specific relationships among athletic involvement, dating, and sexual risk, a second model was tested including product terms for gender and race by dating frequency, athletic activity, and jock identity (see Table IV). Gender did not interact with dating, athletic activity, or jock identity in predicting adolescent sexual risk-taking. For 2 outcome measures, past-year and lifetime frequency of sexual intercourse, the relationship between dating and sexual risk-taking differed by race. A significant interaction of race and jock identity was also found for each of the 4 sexual risk measures.

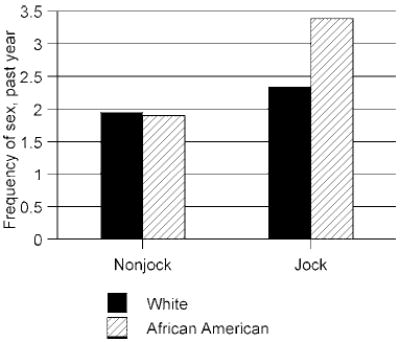

Separate, race-specific models were constructed to probe the significant interaction of race and jock identity (data not shown in tabular form). For both African American and White adolescents, higher levels of risk were associated with male gender, greater age, lower socioeconomic status, lower levels of family cohesion, and more frequent dating. However, most of these effects were somewhat weaker for African American respondents. Athletic activity was significantly associated with lower levels of sexual risk for White but not for African American adolescents. Most notably, African American jock identity was a strong and significant indicator of both the multivariate risk factor and each of the univariate sexual risk factors; White jock identity weakly predicted age of sexual onset only, and was not significantly associated with any of the other measures of risk. The significant interaction of race and jock identity for 1 representative measure, past-year frequency of sexual intercourse, has been plotted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Interaction of race and jock identity in predicting reported past-year frequency of sexual intercourse (0 = never; 1 = once; 2 = 2–3 times; 3 = 4–5 times; 4 = 6–9 times; 5 = 10+ times).

DISCUSSION

This analysis addresses several nagging questions associated with the study of sport and adolescent sexual behavior. First, is any reductive effect of athletic involvement on female adolescent sexual activity a product of female jocks’ choices not to take sexual risks, or of their relatively limited opportunities to do so? Second, what is it about adolescent athletic involvement that affects sexual risk-taking: Is it organized athletic participation per se, which carries with it both time constraints and an accompanying social network, or the psychosocial identity associated with sports involvement? Third, is the relationship between sports and adolescent sexual risk monolithic, or does it vary by gender and/or race?

Dating

Cultural resource theory suggests that male adolescents use the enhanced status they gain from sports as a resource in the sexual negotiation process, a process which may include more frequent dating. However, female athletes may not experience parallel status gains. Indeed, one often-raised challenge to the theory is the argument that girls who participate in sports may be more likely to be perceived as lesbian (Blinde and Taube, 1994), and thus to have fewer opportunities with respect to heterosexual dating, heterosexual relationships, and heterosexual risk-taking (Holland and Andre, 1994; Kane, 1988). This analysis tested the proposition that athletic involvement is related to dating behavior in gender-specific ways. As expected, dating frequency was a good predictor of increased sexual risk. Our hypothesis with respect to gender differences in the relationship between jock identity and dating (H1) was supported: Males who claimed a jock identity reported more frequent dating than their nonjock counterparts, whereas the dating frequency of female jocks did not differ significantly from that of female nonjocks. Although further research is called for in order to sort out sport-related differences in dating behavior, as well as the potential impact of lingering lesbian stigmatization (particularly for girls affiliated with “sex-inappropriate” sports), these findings suggest that if female jocks take fewer sexual risks, they do so out of choice, not necessity.

Jock Identity Vs. Athletic Activity

This study highlights the importance of careful operationalization of measures of adolescent sports involvement. Previous research has indicated strong, gender-specific effects of athletic participation on sexual behavior (e.g., Miller et al., 1998a,b). However, the present analysis uncovered intriguing differences between the effects of athletic activity and jock identity. Whereas time spent playing sports constituted a buffer against sexual risk, identification with the jock label was actually associated with higher levels of sexual risk-taking.

There are several mechanisms whereby sports participation might directly or indirectly affect sexual risk. Organized sports team membership fills available leisure time with structured, supervised activity, leaving fewer opportunities for sexual activity altogether–risky or otherwise (Miller et al., 1998a), and can enhance social status as well (Holland and Andre, 1994; Kane, 1988; Suitor and Carter, 1999). However, the correlation between athletic participation and jock identity is significant but not particularly strong; thus these constructs must be examined independently with respect to their links to adolescent sexual behavior. Although cultural resource theory has been tested with respect to athletic participation per se, no previous research has explored the relationships among jock identity, gender, race, and sexual risk. Our findings, particularly the strong and consistently positive associations between jock identity and each of our sexual risk outcome measures, demonstrate that the impacts of objective (athletic activity) and subjective (jock identity) athletic involvement on adolescent sexual behavior differ markedly. It seems clear that the development of a jock identity has implications for normative expectations regarding the appropriateness of sexual risk-taking that, due to data limitations, we have only begun to address here. Future research will need to test directly for self-esteem and gendered sexual norms as mediating factors in the relationship between jock identity and sexual risk-taking.

Cultural resource theory suggests that sport affects adolescent sexual behavior in two ways: by influencing adherence to conventional cultural scripts for gendered behavior, and by enhancing the social capital used to negotiate sexual relationships. Although both are socially constructed, holding a jock identity presumably affects social capital less than actual athletic participation does, since the latter necessarily requires explicit peer awareness of one’s athlete status and thus has direct implications for status resources. Therefore, in theorizing the effects of jock identity, we have drawn largely on the cultural scripting aspect of cultural resource theory, setting aside or holding as constant as possible the matter of exchange resources.

A caveat is required with respect to our use of the term “jock” to describe a psychosocial identity associated with sports. Although some researchers have used the terms “athlete” and “jock” interchangeably for rhetorical purposes (e.g., Suitor and Carter, 1999), the extent to which these identities actually overlap remains unclear. While measures such as Brewer et al.’s (1993) Athletic Identity Measurement Scale assess the strength and exclusivity of identification with the athlete role, using statements such as “Sport is the most important part of my life” and “Most of my friends are athletes,” no extant research has satisfactorily defined the parameters of a “jock” identity. In fact, studies of crowd affiliations have conventionally asked individuals to identify themselves or others as “jocks,” without providing any specific parameters for operationalizing the term. However, there is preliminary evidence to suggest that “athletes” and “jocks” are not equivalent constructs. Compared to athletes, jocks may be more closely associated with problem behaviors such as bullying (Wilson, 2002) and heavy drinking (Ashmore et al., 2002). Future research, using specific and rigorous operationalization not yet available in an established data set, will be needed in order to sort out more clearly how athletes and jocks differ.

Gender and Racial Variations

Since a jock identity runs contrary to a traditional feminine script, but reinforces a traditional masculine script, we hypothesized that girls with a jock identity would engage in less sexual risk-taking, whereas boys with a jock identity would engage in more sexual risk-taking. However, our hypothesis that gender interacts with jock identity in predicting sexual risk behavior (H2) was not supported. Male jocks did in fact engage in more sexual risk than male nonjocks, but—contrary to expectation—female jocks did as well. The finding that jock identity was associated with greater sexual risk irrespective of gender challenges the core premise of cultural resource theory that athletic involvement weakens female adherence to a conventionally passive feminine cultural script and thus reduces sexual activity and risk-taking. While alternative explanations must yet be ruled out, we suggest that, whereas participation in sports enhances the status resources that adolescent girls need in order to enforce standards of safety in their sexual relationships, internalization of the “jock” label is indicative rather of the adoption of certain athletic subcultural norms, among them a higher acceptance of risk.

Racial variations in the relationship between jock identity and adolescent sexual risk-taking also raise important questions. Our hypothesis that race interacts with jock identity in predicting sexual risk behavior (H3) was supported; African American jocks reported generally higher levels of sexual risk-taking than African American nonjocks, although contrary to expectation, we did not find that White jocks took fewer risks than their nonjock counterparts. Why is the relationship between jock identity and sexual risk stronger for African American teens than White teens? The nature of the available data preclude a definitive answer to this question. However, we speculate that being a “jock” means something quite different to White and African American teens. One reason might be that, in a society where racial minorities continue to face substantial marginalization, African American claimants to this identity tend to have a more truncated range of easily accessible alternative identities, just as they have fewer alternative sources of social status. If so, then they may buy into the sexually aggressive ethic associated with being a jock more than their White peers, for whom the jock identity is more diffused.

One clue to this dynamic may lie in the differential race/gender patterns for dating vis-a-vis sexual risk, particularly among male adolescents. We observed that, for African American boys, jock identity is a powerful predictor of sexual risk-taking (Fig. 1), but not dating (Table II); conversely, dating appears to matter a great deal for White boys, but jock identity does not. Our measures of both jock identity and dating frequency relied on respondents’ interpretations of these constructs. It is possible, for example, that White boys are more likely than African American boys to engage in conventionally structured dating behavior (as opposed to informally “hanging out” in mixed-gender groups), or at least to define their social encounters with prospective heterosexual sex partners as “dates.”

Moreover, follow-up analysis indicated that the bivariate correlation between jock identity and athletic activity was 0.29 (p < 0.01) for White boys but −0.01 (p > 0.05, ns) for African American boys. Again, these observations provide conclusive proof of nothing, but invite speculation leading to future confirmatory analyses. We suggest that White male jocks may be more likely to be involved in a range of extracurricular status-building activities that translate into greater popularity overall, as indicated by more frequent dating; whereas African American male jocks may be “jocks” in a more narrow sense that does not translate as directly into overall dating popularity. Furthermore, it may be that White teens interpret being a “jock” in a sport context, whereas African American teens see it more in terms of relation to body (being strong, fit, or able to handle oneself physically). If so, then for Whites, being a jock would involve a degree of commitment to the “jock” risk-taking ethos, but also a degree of commitment to the conventionally approved norms associated with sanctioned sports involvement; whereas for African Americans, the latter commitment need not be adjunct to a jock identity.

Although such interpretations are at this juncture purely speculative, the finding of an interaction between race and jock identity supports the conclusion that the lived experience of athleticism, and its implications for not just sexual behavior but other aspects of peer social interaction as well, vary across racial lines. Racial nuances, preferably extending beyond African American vs. White categories, must feature prominently in future studies of the nexus of athletic identity and sexual risk.

Future researchers must take care in operationalizing adolescents’ subjective and objective experiences of athleticism as a contributor to sexual risk behavior. Owing to data limitations, we were constrained in this study to use a broad but shallow indicator of jock identity, requiring only a prima facie self-report of how well the jock “type” fit the respondent. This measure did not permit us to disaggregate subcultural from psychological aspects of how adolescents and their peers construe this label. Athletic identity has elsewhere been measured as a psychological construct, employing the Athletic Identity Measurement Scale (Brewer et al., 1993). Empirical testing of the gender- and race-specific relationships between this promising measure of athletic identity and adolescent sexual risk-taking would better serve to distinguish between the objective (what one does) vs. subjective (what one perceives oneself to be) athlete.

Though limited in scope, the present study offers some preliminary insights into the causal relationship between jock identity and sexual risk-taking by establishing a temporal order. With one notable exception (Eitle and Eitle, 2002), previous research examining the relationship between athletic participation and adolescent sexual behavior has been cross-sectional or correlational in nature and thus unable to test time-ordered hypotheses. For example, though a number of studies have linked female sports participation with lowered levels of sexual activity, more frequent and reliable use of contraceptives, and/or reduced pregnancy risk, most have not been able to rule out the possibility that girls who take sexual risks self-select out of sports programs by getting pregnant. Eitle and Eitle (2002) examined the lingering effects of female high school athletic participation on sexual and reproductive activities in young adulthood and found that young adult women who had been high school athletes reported fewer lifetime sex partners, and were less likely to have experienced a nonmarital pregnancy, than their nonathletic peers. Future research may profitably link the development of a jock identity over time with subsequent sexual risk-taking.

Understanding adolescent health risk behavior is often confounded by one or more of the factors addressed in this study. Data limitations and sampling constraints have forced some researchers to lump together adolescents of different racial backgrounds, or to restrict their analyses to only one gender. Most of the research to date has been entirely cross-sectional, undermining theoretical attempts to model relationships over time. Other concomitants of sexual risk, such as the dynamics of family relationships or dating behavior, are frequently ignored. Perhaps most seriously, athletes have for the most part been defined in objective and dichotomous terms (athlete vs. nonathlete), based solely on their formal membership on a school-sponsored sports team, irrespective of their subcultural or psychosocial commitment to a sport-related identity. This study lays the groundwork for a more nuanced assessment of the gender- and race-specific relationships between jock identity and adolescent sexual risk.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Joseph Hoffman for his assistance with statistical analysis, and Barbara Dintcheff for her assistance with data preparation and management. This research was supported by NIDA grant #13570 to Grace M. Barnes.

Footnotes

Some athletes reject the term “jock” because of the often-associated negative connotations (e.g., “dumb jock”). The term is used in this analysis for heuristic purposes only; it is not meant to disparage or offend.

This measure too is limited as a global indicator of the context in which sexual bargaining takes place, since it encompasses only one common setting for heterosexual adolescent interaction, and might be interpreted as excluding the common pattern of “hanging out” by mixed-gender groups.

References

- Ashmore RD, Del Boca FK, Beebe M. ‘Alkie,’ ‘frat brother,’ and ‘jock’: Perceived types of college students and stereotypes about drinking. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2002;32:885–907. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes GM, Farrell MP. Parental support and control as predictors of adolescent drinking, delinquency, and related problem behaviors. J Marriage Fam. 1992;54:763–776. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, G. M., Farrell, M. P., and Dintcheff, B. A. (1997). Family socialization effects on alcohol abuse and related problem behaviors among female and male adolescents. In Wilsnack, S., and Wilsnack, R. (eds.), Gender and Alcohol Rutgers Center of Alcohol Studies, Piscataway, NJ, pp. 156–175.

- Barnes, G. M., Farrell, M. P., Welch, K. W., Uhteg, L., and Dintcheff, B. A. (1991). Description and Analysis of Methods Used in the Family and Adolescent Study Buffalo, NY: Research Institute on Alcoholism.

- Barnes GM, Reifman A, Farrell MP, Dintcheff BA. The effects of parenting on the development of adolescent alcohol misuse: A six-wave latent growth model. J Marriage Fam. 2000;62:175–86. [Google Scholar]

- Benda BB, DiBlasio FA. An integration of theory: Adolescent sexual contacts. J Youth Adolesc. 1994;23:403–420. [Google Scholar]

- Blinde EM, Taub DE. Women athletes as falsely accused deviants: Managing the lesbian stigma. Sociol Q. 1992;33:521–533. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer BW, Van Raalte JL, Linder DE. Athletic identity: Hercules’ muscles or Achilles’ heel? Int J Sport Psych. 1993;24:237–54. [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB, Eicher SA, Petrie S. The importance of peer group (‘crowd’) affiliation in adolescence. J Adolesc. 1986;9:73–96. doi: 10.1016/s0140-1971(86)80029-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, B. B., Mory, M. S., and Kinney, D. (1994). Casting adolescent crowds in a relationship perspective: Caricature, channel, and context. In Montemayor, R., Adams, G., and Gullotta, T. P. (eds.), Personal Relationships During Adolescence Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 123–167.

- Carroll JL, Volk KD, Hyde JS. Differences between males and females in motives for engaging in sexual intercourse. Arch Sex Behav. 1985;14:131–139. doi: 10.1007/BF01541658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in sexual risk behaviors among high school students—United States, 1991–2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51(38):856–859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coley RL, Chase-Lansdale PL. Adolescent pregnancy and parenthood: Recent evidence and future directions. Am Psychol. 1998;53:12–166. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Shapiro CM, Powers AM. Motivations for sex and risky sexual behavior among adolescents and young adults: A functional perspective. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;75:1528–1558. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.6.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLamater, J. (1987). Gender differences in sexual scenarios. In Kelley, K. (ed.), Females, Males, and Sexuality: Theories and Research SUNY Press, Albany, NY, pp. 127–139.

- Dodge T, Jaccard J. Participation in athletics and female sexual risk behavior: The evaluation of four causal structures. J Adolesc Res. 2002;17:42–67. [Google Scholar]

- Dolcini MM, Adler NE. Perceived competencies, peer group affiliation, and risk behavior among early adolescents. Health Psychol. 1994;13:496–506. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.6.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EDK Associates for Seventeen Magazine and the Ms. Foundation for Women. (1996). Teenagers Under Pressure New York: EDK Associates.

- Eitle TM, Eitle DJ. Just don’t do it: High school sports participation and young female adult sexual behavior. Sociol Sport J. 2002;19:403–418. [Google Scholar]

- Erkut, S., and Tracy, A. J. (2000). Protective Effects of Sports Participation on Girls’ Sexual Behavior Working Paper No. 301, Center for Research on Women, Wellesley, MA.

- Franklin C, Grant D, Corcoran J, Miller PO, Bultman L. Effectiveness of prevention programs for adolescent pregnancy: A meta-analysis. J Marriage Fam. 1997;59:551–67. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF, Jr, Morgan SP, Moore KA, Peterson JL. Race differences in the timing of adolescent intercourse. Am Sociol Rev. 1987;52:511–518. [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon, J. H., and Simon, W. (1973). Sexual Conduct: The Social Sources of Human Sexuality Aldine, Chicago, IL.

- Harvey SM, Spigner C. Factors associated with sexual behavior among adolescents: A multivariate analysis. Adolescence. 1995;30(118):253–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland A, Andre T. Athletic participation and the social status of adolescent males and females. Youth Soc. 1994;25:388–407. [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM. Differentiating peer contexts and risk for adolescent substance use. J Youth Adolesc. 2002;31:207–220. [Google Scholar]

- Kane MJ. The female athletic role as a status determinant within the social systems of high school adolescents. Adolescence. 1988;23:253–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, D. (1997). No Easy Answers: Research Findings on Programs to Reduce Teen Pregnancy The National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy, Washington, DC.

- Kokotailo PK, Koscik RE, Henry BC, Fleming MF, Landry GL. Health risk taking and human immunodeficiency virus risk in collegiate female athletes. J Am Coll Health. 1998;46:263–68. doi: 10.1080/07448489809596002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Prinstein MJ, Fetter MD. Adolescent peer crowd affiliation: Linkages with health-risk behaviors and close friendships. J Pediatr Psychol. 2001;26:131–43. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/26.3.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz CD, Schroeder PJ. Endorsement of masculine and feminine gender roles: Differences between participation in and identification with the athletic role. J Sport Behav. 1999;22:545–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lauritsen JL. Explaining race and gender differences in adolescent sexual behavior. Soc Forces. 1994;72:859–886. [Google Scholar]

- Laws, J. L., and Schwartz, P. (1977). Sexual Scripts: The Social Construction of Female Sexuality Dryden, Hinsdale, IL.

- Males M. School-age pregnancy: Why hasn’t prevention worked? J Sch Health. 1993;63:429–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1993.tb06075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BC, Moore KA. Adolescent sexual behavior, pregnancy, and parenting: Research through the 1980s. J Marriage Fam. 1990;52:1025–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Miller BC, Norton MC, Curtis T, Hill EJ, Schvaneveldt P, Young MH. The timing of sexual intercourse among adolescents: Family, peer, and other antecedents. Youth Soc. 1997;29:54–83. [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Barnes GM, Melnick MJ, Sabo D, Farrell MP. Gender and racial/ethnic differences in predicting adolescent sexual risk: Athletic participation vs. exercise. J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:436–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Hoffman JH, Barnes GM, Farrell MP, Sabo D, Melnick MJ. Jocks, gender, race, and adolescent problem drinking. J Drug Educ. 2003;33:445–462. doi: 10.2190/XPV5-JD5L-RYLK-UMJA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, K. E., Farrell, M. P., Sabo, D., Barnes, G. M., and Melnick, M. J. (1998a, March). Idle hands? Extracurricular activities, gender, and adolescent sexual behavior. Roundtable presented at the Annual Convention, Eastern Sociological Society, Philadelphia.

- Miller KE, Sabo D, Farrell MP, Barnes GM, Melnick MJ. Athletic participation and sexual behavior in adolescents: The different worlds of boys and girls. J Health Soc Behav. 1998b;39:108–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, K. E., Sabo, D., Farrell, M. P., Barnes, G. M., and Melnick, M. J. (1999a, August). Athletic participation and adolescent sexual behavior: Where race and gender intersect. Paper presented at the Annual Convention, Society for the Study of Social Problems, Chicago.

- Miller KE, Sabo D, Farrell MP, Barnes GM, Melnick MJ. Sports, sexual activity, contraceptive use, and pregnancy among female and male high school students: Testing cultural resource theory. Sociol Sport J. 1999b;16:366–87. doi: 10.1123/ssj.16.4.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer S, Baldwin W. Demographics of adolescent sexual behavior, contraception, pregnancy, and STDs. J Sch Health. 1992;62:265–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver MB, Hyde JS. Gender differences in sexuality: A meta-analysis. Psychol Bulletin. 1993;114:29–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson, D. H., Portner, J., and Lavee, Y. (1985). FACES III University of Minnesota, Family Social Science, St. Paul, MN.

- Page RM, Hammermeister J, Scanlan A, Gilbert L. Is school sports participation a protective factor against adolescent health risk behaviors? J Health Educ. 1998;29:186–192. [Google Scholar]

- Pate RR, Trost SG, Levin S, Dowda M. Sports participation and health-related behaviors among U.S youth. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:904–11. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.9.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rome ES, Rybicki LA, DuRant RH. Pregnancy and other risk behaviors among adolescent girls in Ohio. J Adolesc Health. 1998;22:50–55. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(97)00160-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabo, D., Miller, K. E., Farrell, M. P., Barnes, G. M., and Melnick, M. J. (1998). The Women’s Sports Foundation Report: Sport and Teen Pregnancy Women’s Sports Foundation, East Meadow, NY.

- Sabo D, Miller KE, Farrell MP, Melnick MJ, Barnes GM. High school athletic participation, sexual behavior and adolescent pregnancy: A regional study. J Adolesc Health. 1999;25:207–16. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelli, J. S., Lindberg, L. D., Abma, J., Sucoff, C., and Resnick, M. (2000). Adolescent sexual behavior: Estimates and trends from four nationally representative surveys. Fam. Plan. Perspect. 32: 156–165, 194. [PubMed]

- Savage MP, Holcomb DR. Adolescent female athletes’ sexual risk-taking behaviors. J Youth Adolesc. 1999;28:595–602. [Google Scholar]

- Simon W, Gagnon JH. Sexual scripts: Permanence and change. Arch Sex Beh. 1986;15:97–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01542219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suitor JJ, Carter RS. Jocks, nerds, babes and thugs: A research note on regional differences in adolescent gender norms. Gender Issues. 1999;3:87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Suitor JJ, Reavis R. Football, fast cars, and cheerleading: Adolescent gender norms, 1978–1989. Adolescence. 1995;30(118):265–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S, Dent CW, Stacy AW, Burciaga C, Raynor A, Turner GE, Charlin V, Craig S, Hansen WB, Burton D, Flay BR. Peer-group association and adolescent tobacco use. J Abnorm Psychol. 1990;99:349–52. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton A. The courtship process and adolescent sexuality. J Fam Issues. 1990;11:239–273. [Google Scholar]

- Tolman DL, Porche MV. The adolescent femininity ideology scale: Development and validation of a new measure in girls. Psychol Women Q. 2000;24:365–376. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2000). Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health (2nd edn.). U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

- White CP, White MB. The Adolescent Family Life Act. J Clin Child Dev. 1991;20:50–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson B. The ‘anti-jock’ movement: Reconsidering youth resistance, masculinity, and sport culture in the age of the Internet. Sociol Sport J. 2002;19:206–233. [Google Scholar]

- Zill, N., Nord, C., and Loomis, L. (1995). Adolescent Time Use, Risky Behavior, and Outcomes: An Analysis of National Data Westat, Rockville, MD.