Abstract

I examine the provision of mental health services to Medicaid recipients in New Mexico to illustrate how managed care accountability models subvert the allocation of responsibility for delivering, monitoring, and improving care for the poor. The downward transfer of responsibility is a phenomenon emergent in this hierarchically organized system. I offer three examples to clarify the implications of accountability discourse. First, I problematize the public–private “partnership” between the state and its managed care contractors to illuminate the complexities of exacting state oversight in a medically underserved, rural setting. Second, I discuss the strategic deployment of accountability discourse by members of this partnership to limit use of expensive services by Medicaid recipients. Third, I focus on transportation for Medicaid recipients to show how market triumphalism drives patient care decisions. Providers and patients with the least amount of formal authority and power are typically blamed for system deficiencies.

Keywords: accountability, health policy, managed care, Medicaid, mental health

Managed care in the Medicaid arena has been widely embraced by state policy makers as a means for reducing service delivery costs and improving the quality of health care for impoverished populations (Maskovsky 2000). This major policy reform is embedded in wider processes of welfare state restructuring (Clarke 2004; Maskovsky 2000; Morgen 2001; Morgen and Maskovsky 2003; Rylko-Bauer and Farmer 2002). Devolution and privatization are integral to this restructuring process and are pivotal to the transformation of state Medicaid systems nationwide. The restructuring process valorizes the application of corporate managerial techniques that will promote efficient and “transparent” decision-making processes in the public sector (Clarke and Newman 1997:30). This ideology of managerialism promises to transform the welfare state from an assemblage of “unresponsive, paternalistic, and leaden bureaucracies” by promoting the “rigorous discipline” required to produce cost-effective services in the otherwise wasteful and chaotic public sector (Clarke and Newman 1997: 34–38).

With its emphasis on instituting high standards of “accountability,” managed care is seen as an important means to impart discipline in the Medicaid arena and in mental health service delivery. Managed care companies specializing in mental health, referred to as behavioral health organizations (BHOs), have fundamentally changed how such services are delivered. BHOs use accountability models as “instruments of power and surveillance” (Herzfeld 1992:66), subjecting frontline service providers (including mental health clinicians) and Medicaid recipients to increased scrutiny by monitoring and limiting their use of services.

Formal definitions of accountability that underlie frameworks for public and corporate administration within this country derive from Euro American philosophical traditions and reflect a rationalist conception of responsibility (Herzfeld 1992) in which responsible action is synonymous with morally or legally correct action and individuals are held liable and potentially punishable for causing harm (Harmon 1995). “Blame” is an implicit component of the prevailing conception of responsibility. Further, within these traditions, accountability has been defined as:

an authoritative relationship in which one person is formally entitled to demand that another answer for—that is, provide an account of—his or her actions; reward or punishments may be meted out to the latter depending on whether those actions conform to the former’s wishes. To say that someone is accountable . . . is to say that he or she is liable for sanctions according to an authoritative rule, decision, or criterion enforceable by someone else. [Harmon 1995:25]

While responsibility and accountability are portrayed as objective and measurable phenomena in the increasingly corporate Medicaid arena, the act of determining correct action, including the use of quality monitoring data to assess the provision and the cost effectiveness of mental health care, is beset with ambiguities.

This ethnographic study of the provision of mental health services to Medicaid recipients in New Mexico illustrates how the application of managed care accountability models can subvert the very phenomena that they claim to enforce, including the allocation of responsibility for delivering, monitoring, and improving health services for the poor.1 While other ethnographic research illuminates the impact of state welfare restructuring initiatives on recipients, this study offers insight into how such initiatives affect the work of state officials (Morgen 2001), corporate administrators, and frontline service providers. I illustrate how these key players deployed accountability discourses to absolve themselves from blame for the Medicaid program’s deficiencies, which are reviewed elsewhere (Willging, Waitzkin, and Wagner 2004). As seen in the anthropological literature on state bureaucratic practices, these discourses facilitate “buck-passing” (Gupta 1995; Herzfeld 1992) and are abetted by the ideological claim that the free market, rather than the archaic and inefficient welfare state, is the panacea for the health care problems of the poor (Goode and Maskovsky 2001).

Recent work in U.S. anthropology has paid considerable attention to the reentrenchment of blame ideologies that has accompanied the rise of domestic neoliberalism (Goode and Maskovsky 2001; Kingfisher 2001; Morgen and Maskovsky 2003). Domestic neoliberalism encourages the “primacy of profit over service provision” by allowing states to turn control over public health and welfare programs to private companies (Goode and Maskovsky 2001:8).

The transformation of public health and welfare programs, such as Medicaid, set in motion by domestic neoliberal agendas, reinforces preexisting blame ideologies against the poor (Kingfisher 1996, 2001; Lipsky 1980). Privatization has shifted the responsibility for health care from the public to the private, here referring not simply to the corporate sector, but to the more personal domains of family and community, which are expected to assume even greater roles with regard to the provision of care (Clarke and Newman 1997). While placing the onus on them to become responsible for their health care needs (Goode and Maskovsky 2001:7–8), the new market orientation of the Medicaid program basically aims to reconfigure the poor from “passive recipients of welfare-state services” into self-empowered consumers (Morgen and Maskovsky 2003:322).

The process of state welfare restructuring also enables state officials to minimize their direct involvement in Medicaid services. At present, little ethnographic work documents how such officials act on behalf of the state (Gupta 1995). In this article, I underscore how state officials invoke “a ready-made rhetoric” of devolution, contracting, and privatization to uphold the “the current balance of power” (Herzfeld 1992:93), the locus of which is perceived to be the “partnership” between the state government and its managed care contractors. This rhetoric reinforces the “right to be unaccountable” for state officials, which is tantamount to possessing power (Herzfeld 1992:122) and facilitates buck passing or the shifting of blame for program deficiencies from the state and its corporate partners to frontline service providers and low-income patients.

Background

Managed care proponents argue that their approach to health services brings two needed forms of accountability to the public sector: market and professional. The basic assumption of market accountability is that the market will produce needed information that purchasers (i.e., the state government) and consumers (i.e., Medicaid recipients) will use to choose among competing health plans. The basic premise of professional accountability is that providers require external monitoring to assure that they are delivering quality, cost-effective care.

More specifically, under dominant managed care arrangements, the state government contracts with a private sector middleman, a managed care organization, or MCO, which accepts a single capitation or one payment for each Medicaid recipient enrolled in its health plan per year to cover the cost of services. The MCO can be sanctioned if it does not adhere to specified standards of care (Fossett et al. 1999). Information about MCO performance is to be disseminated to the state and to Medicaid recipients so they can make informed choices among the different MCOs and the services that they offer (Daniels and Sabin 1998; Donaldson 1998). In theory, competition ensures that the MCOs are accountable to patients and to the state, as market forces reward those MCOs that deliver quality care with expanded patient enrollment and lucrative service contracts within the public sector. MCOs that cannot demonstrate high quality performance are considerably disadvantaged when competing for these contracts.

As per professional accountability, state officials across the country have customarily relied on the special trust relationship between provider and patient as a guarantee of quality care for Medicaid recipients. The nature of this relationship is traceable to the Hippocratic tradition. This time-honored trust relationship requires providers to make decisions that are in the best interests of patients and prohibits them from exploiting patients for personal gain. In managed care environments, however, MCOs have imposed uniform standards of professional accountability, displacing the autonomous decision-making capacities of the provider, who is required to practice in accordance with the expectations of MCOs (Donaldson 1998). The rationale for this change is that providers vary too much in clinical judgments and practice styles, with no assurances of quality care for patients or cost effectiveness for payers (Light 2000). The MCOs’ expectations for professional accountability nevertheless reflect the more compelling demands of keeping costs low and generating profits. Utilization review is the chief mechanism by which these organizations control the economic burden incurred by the clinical activities of providers. As proponents of managed care argue, making providers answerable to payers (or market accountability) for the money that they request for service provision will, in due course, bring about professional accountability. By changing the ability of providers to control revenue streams, transforming them into custodians of expensive services, and by monitoring their performance, health care providers will become professionally answerable to both MCOs and purchasers (i.e., the state government), rather than to patients exclusively (Lofland and Nash 2001).

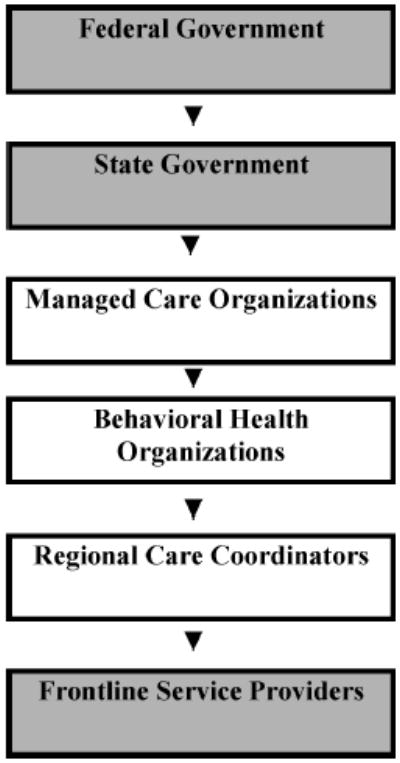

I examine how market and professional accountability, two major organizational principles of Medicaid managed care (MMC), placed rival demands on persons involved in delivering mental health services in the rural state of New Mexico. In 1997, the state government advanced a radical departure from the traditional fee-for-service system, which is shaded in gray in Figure 1, by awarding contracts to multiple MCOs to provide physical and mental health services to Medicaid recipients. Previously, providers billed the Medicaid program directly for services that they deemed as necessary. Under managed care, the state contracted with three MCOs, which subcontracted with three BHOs to manage the delivery of mental health services. As depicted in Figure 1, these organizations then contracted with three regional care coordinators, adding another administrative and financial layer to the system. Finally, the coordinators contracted with frontline service providers to deliver care.

Figure 1.

Medicaid Organizational Structure and Funding Stream.

This new system was intended to promote efficiency and transparency in administrative and clinical decision making, which the prior Medicaid bureaucracy was thought to lack. In this system of nested hierarchies, the state government was to oversee the financial activities and performance of MCOs. The MCOs regulated the activities of BHOs, which, in turn, determined what services would be provided by frontline service providers. Accordingly, those providers not in private practice were accountable to employers. Patients were located on the bottom rung of this multilayered managed care system. I offer three examples to illustrate how competing notions of accountability were articulated, enacted, and contested in these hierarchical situations.

The first example spotlights the public–private partnership between the state and BHOs to illuminate the complexities of exacting state oversight in a medically underserved, rural setting where the threat of MCO and BHO withdrawal from the Medicaid program is omnipresent, mainly because the potential profit margin is so low (Silberman et al. 2002). The second example elucidates the paradoxes that emanate from the deployment of market and professional accountability arguments by state officials and BHO administrators, who want to decrease use of costly residential treatment services and simultaneously create less expensive community-based alternatives for Medicaid recipients. The third example focuses on transportation under Medicaid and shows the subtle ways that the ideology of market triumphalism, or the push for profit (Goode and Maskovsky 2001), drives decisions regarding patient care.

State Government–MCO Relations

In contrast to public bureaucracies, characterized in neoliberal discourse as “seemingly stupid and irrational systems of rules” that are staffed by “street-level bureaucrats” whose decision-making processes cannot be controlled (Clarke and Newman 1997:67), private sector managerialism aims to ensure that employees are accountable for performance. For example, MCO and BHO administrators are directly answerable to higher level corporate officers and shareholders, who are interested in enhancing service efficiency and generating profits. Although the intent of Medicaid privatization is to introduce this form of accountability into the public sector, it is important to remain aware that state officials do not necessarily relinquish responsibility for public health and welfare programs once privatization has occurred, as they must now turn attention to monitoring contracts between the state government and its corporate partners (Fossett et al. 1999).

At the same time as state officials are entrusted to regulate the activities of MCOs and BHOs, they operate under the threat that these corporations will withdraw from the Medicaid marketplace if state oversight becomes too onerous (Fossett et al. 1999). In a rural market such as New Mexico, where there are small numbers of potential enrollees and the costs incurred by the logistics of delivering care are significantly higher than those in urban areas, this threat of withdrawal complicates, and essentially inverts, the power relationship between the state government and its MMC contractors. This threat, I argue, compromises market accountability as an organizing principle of MMC and diminishes the state’s capacity to become a prudent purchaser of mental health care, while potentially detracting from constituents’ concerns about services (or public accountability). In other words, this threat ensures that mental health services are constituted as a seller’s market.

Ironically, although the intent of privatization is to decrease the involvement of state officials in administering Medicaid programs, their involvement should increase as a result of their new contract monitoring responsibilities (Fossett et al. 1999). In New Mexico, however, the state Medicaid agency lacked both the technical staff and the infrastructure needed to collect, analyze, disseminate, and act on performance information, activities that are considered essential to the attainment of accountability in any managed care system (Fossett et al. 1999). The state Medicaid agency’s director explained that insufficient funding and staffing shortages had contributed to the state government’s inability to analyze and interpret the Medicaid encounter data that had been amassed between 1997 and 2000 (Field notes, 8/24/00). These encounter data consisted largely of information regarding the purpose and outcome of all provider–patient interactions occurring in the new Medicaid system. As such, these data were intended to furnish indicators of MCO and BHO performance and, thus, to play an important role in evaluating the MMC system.

However, the state Medicaid agency’s director was admittedly reluctant to publicly release encounter data and other monitoring data for fear that providers and patient advocates would use it to criticize the new Medicaid system. In response to claims from provider and advocacy groups that the state Medicaid agency had been delinquent in providing the state legislature and the public with timely access to all data and financial records pertinent to the new Medicaid system, the director stated: “From a managerial perspective, it’s good to have data to know what’s going on. But when you’re using the data to see what’s wrong rather than to fix the system, then that’s bad” (Field notes, 8/24/00).

In an effort to monitor system performance, the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law—a national civil rights organization representing individuals with serious mental illness—analyzed the raw encounter data from the state Medicaid agency, revealing considerable underutilization by Medicaid recipients in New Mexico of the intensive community-based services designated by the U.S. surgeon general as effective for individuals with serious mental health problems. Such services include case management, psychiatric rehabilitation, psychotherapy, and medication management (Bazelon Center 2000).

In the state Medicaid agency’s desire to protect mental health services under managed care and to justify the control over market share exerted by MCOs and BHOs, the director played down much of the negative feedback regarding the new managed care system that was offered by providers, categorizing them as “special interests” who were displeased that they could no longer profit from Medicaid: “When you talk of providers, you get into issues of money, livelihood, and the lack of control. Now doctors are in situations where people are telling them you can’t do this anymore—order all these tests, institutionalize someone, prescribe a certain drug rather than a generic medication. There’s oversight there” (Field notes, 8/24/00). Because of their misuse and abuse of Medicaid under the fee-for-service structure, the director believed that providers could not be relied on to impart unbiased views about the new system (Field notes, 8/24/00).

By characterizing providers as special interests, state officials cast doubt on the motives of these presumed “refusers” or “resisters” of MMC reform, while constructing themselves as “innocent of any taint of bad faith” (Clarke and Newman 1997:53). In accordance with neoliberal ideology, they deemed change instigated by devolution, contracting, and privatization as natural, inevitable, and absolutely necessary to curtail Medicaid expenditures (Clarke and Newman 1997), serving the best interests of the purchaser and the consumer alike. Even the director’s superior, the secretary of the Human Services Department, underscored the difficulty of “getting the straight story from professionals,” claiming that providers were unable to “set aside their personal motives and [to] give the straight scoop about what is best for patients” (Field notes, 5/31/02). She added, “They were so wrapped up economically [in the Medicaid system] that they couldn’t see what was right for patients” (Field notes, 5/31/02).

While minimizing the perceptions of providers, state officials openly espoused a discourse of partnership between the state Medicaid agency and the managed care contractors. The state Medicaid agency director clarified: “As far as the state’s relationship with the MCOs, we view them as partners with us. We made a decision early on to work with them . . . . We try to do things in a nonconflictive way. We ask them instead of threatening them. Typically what happens is the problem gets taken care of” (Field notes, 4/5/00).

However, the state Medicaid agency could not evade controversy surrounding its nonconflictive role in this partnership, as several legal actions called into question both professional and market accountability in the new Medicaid system. In 1998, plaintiffs in a lawsuit argued that this system failed to meet the needs of children with chronic mental health conditions. One year later, a legal audit commissioned by the state’s attorney general revealed that New Mexico’s Medicaid system lacked adequate appeal processes and protections of patients’ rights, assurances of timely and appropriate referrals, and assurances that the managed care contractors fairly represented the mental health services they delivered (Willging, Waitzkin, and Wagner 2004).

Two financial audits commissioned by the state legislature added to the controversy. The audits concluded that new Medicaid system lacked adequate capacity to deliver mental health care. The first audit revealed that the state Medicaid agency’s projected savings for the Medicaid program of $125 million would not occur, and that the system was operating under a substantial deficit. This audit suggested that the state Medicaid agency was not effectively monitoring consumer complaints and grievances or collecting reliable encounter data with which to evaluate the system’s impacts (Legislative Finance Committee 2000a). The second audit demonstrated that the system’s multitiered design diverted financial resources to administrative intermediaries, as only 55 percent of MMC funds earmarked for mental health services in 1999 were distributed to actual providers. In the second audit, access problems were attributed to the cumbersome service authorization procedures required by BHOs to ensure professional accountability (Legislative Finance Committee 2000b).

An arm of the executive branch, the state Medicaid agency refuted such findings and instead cited the results of an external audit that the agency itself had commissioned. Rather than trace the distribution of mental health monies starting at the level of the MCOs, the state Medicaid agency’s audit traced the dispersal of these monies starting at the level of the BHOs. This audit indicated that 85 percent of direct service dollars was paid to providers, with BHOs retaining 15 percent of the funds for administration and profit. Nonetheless, this audit did not take into account those monies for mental health services that the MCOs had withheld from the BHOs and retained for their own coffers (William M. Mercer, Inc. 2000).

The conflicting results of both audits raise concerns regarding the effectiveness of market accountability in controlling Medicaid expenditures while also improving access and quality of care. Among these concerns is whether market accountability is possible, given that some state officials are under pressure to withhold information on managed care plans’ service performance and cost effectiveness from colleagues and from the public at large and that the executive and legislative branches of the state government are unable to agree on strategies for measuring and monitoring the performance of MCOs and BHOs. Without such strategies, the ability of the state government to become a prudent purchaser of mental health services for Medicaid recipients is called into question. Moreover, if the state Medicaid agency refuses to act on evidence that access and quality of care have been compromised under managed care, market accountability cannot be reached, though market triumphalism is sustained.

Herzfeld (1992) asserts that “accountability is what many public officials invest enormous amounts of effort in short-circuiting or avoiding” (p. 122). Ironically, the safeguards expressly intended to ensure market accountability and the public’s welfare, including mechanisms for the state to objectively monitor the quality of care, use of services, and fiscal performance, are not impervious to manipulation (Herzfeld 1992). Rather than reassess the shortcomings of market accountability as an organizing principle of the new Medicaid system, key state officials focused on the materialism of disgruntled providers and on managed care as a tool to instill frugality in clinical work. By emphasizing the possible avarice of providers and ignoring that of corporations, they shifted blame downward in the Medicaid hierarchy and underscored managed care’s worth for promoting corporate managerialism to assure professional accountability, despite undermining the sacrosanct trust relationship between providers and patients. The deflective function of these arguments prevented a consideration of the inverted power dynamics of the public–private partnership and prevented state officials from critically reflecting on their incapacity to perform oversight responsibilities adequately.

Residential Treatment and the New Continuum of Care

The initial rationale for adopting a managed care approach in New Mexico was based on state officials’ opinions that mental health clinicians (and physicians in general) were not adequately self-regulating their practices under the Medicaid fee-for-service system and were therefore violating trust relationships with patients. Reminiscent of arguments for psychiatric deinstitutionalization, which were originally promulgated as far back as the 1950s and the 1960s, state officials in New Mexico claimed that Medicaid recipients were being placed in institutional environments—specifically in residential treatment—for prolonged periods of time, although their conditions did not always warrant such intensive care and clinicians did not demonstrate that patients benefited from these services.

State officials argued that under the fee-for-service system, residential treatment consumed a disproportionate amount of Medicaid funds. Instead, under managed care, community-based alternatives including day treatment, outpatient therapy, and case management, would be established and clinicians would be retrained to use expensive services like residential treatment in only rare cases. In time, the development of such alternatives would further the neoliberal goal of transferring responsibility for the care of the poor from the state to the local level.

Utilization review, the process by which managed care companies evaluate medical necessity and authorize the use of services, emerged as the mechanism to rectify problems of inadequate treatment planning by clinicians (Donald 2001). While expressly intended to instill professional accountability among clinicians, utilization review limited expenditures for care by closely limiting length of residential treatment stays and number of outpatient counseling visits. Clinicians also observed that utilization review channeled Medicaid recipients requiring highly specialized services into less specialized services.

One psychologist at a residential treatment center stated that he and his coworkers had to interact with unknown utilization reviewers, whom he called “strangers.” He suggested that these strangers dictated treatment: “We had to serve who we were told to serve, even kids who were inappropriate for our milieu and not appropriate for our level of care. There was no good communication of what you, the clinician, needed to do. But if you didn’t do it, you wouldn’t get paid” (Field notes, 12/13/99). Overall, mental health clinicians were suspicious of utilization review practices because the management of services by an external third party limited referrals and expenditures for specialty services, interfered with their clinical judgments and trust relationship with patients, contributed to decreased revenues, and also disrupted existing relationships among providers.

However, BHO administrators attributed the aversion of clinicians to utilization review to the fact that such reviews prevented overreliance on pricey therapeutic modalities like residential treatment. Echoing earlier arguments on behalf of psychiatric deinstitutionalization, one BHO administrator clarified:

Historically, the residential treatment centers were abused and kids were kept too long in them. The programs didn’t have the best interests of the clients in mind. They would hold on to them and keep them way too long. This wasn’t doing the kids any good. When we began utilization review we demanded that residential treatment centers show valid reasons for a client to remain in treatment for extended stays. A lot of agencies had such poor records and staffs that they couldn’t provide clear documentation on their clients. Some agencies were chaos. [Field notes, 6/5/00]

As an alternative to conventional residential treatment, BHO administrators espoused a commitment to services that enhanced family involvement in the care of the mentally ill and did not separate patients from communities.

Utilization review demanded that clinicians turn to less costly forms of community-based services, which were considered more effective than residential treatment. In 2000, 3 years into the new system, clinicians, Medicaid recipients, and advocates claimed that 54 percent of residential treatment beds in the state had been terminated due to the refusal of utilization reviewers to authorize use by Medicaid recipients (Legislative Finance Committee 2000b). They claimed that many refusals were driven by the BHOs’ interest in saving money and thus lacked sound clinical rationales and, moreover, that the availability of community-based services had declined since managed care’s onset in 1997 (at least 60 youth-oriented mental health programs closed between 1998 and 2001).

In response, the BHO administrators suggested that although the providers were blaming the new system for this reduction in services, they were not “recognizing their own deficiencies” (Field notes, 6/5/00). From their perspective, providers misconstrued the mission of the BHOs, which was to improve quality of services while decreasing inappropriate expenditures. The BHO administrators characterized the providers as “special interests” who resisted Medicaid reform because they stood to profit from business as usual. One BHO administrator explained, “In Medicaid there are no limits to service as long as [the requests] meet medical necessity criteria” (Field notes, 2/23/00). Conventional residential treatment, the BHO administrators consistently argued, did not meet these criteria. Commenting on the closure of residential treatment centers in New Mexico since the introduction of MMC, a second BHO administrator stated, “Many that have shut down are selling oranges when we want apples. . . . We try to avoid residential treatment not because we don’t pay for that but because we don’t want to violate the tenets of good treatment” (Field notes, 4/25/00).

The claim that providers were responsible for the diminished mental health care infrastructure underscored the predicament that BHO administrators were in. The BHOs were operating under several constraints, many of which were financial. The funds that BHOs received from MCOs were stretched thin between existing programs that provided care and the development of new community-based services. These funds also supported the multitiered administration of the Medicaid mental health system, which left fewer dollars to pay for new services, especially after MCOs claimed their cut of the pie. In addition to improving the fiscal performance of their respective corporations, the BHO administrators were to penetrate a medically underserved rural market and contend with the hopes that state officials and others had pinned naively on managed care. The untenable nature of this situation was highlighted by one BHO administrator: “There was a false belief in rural areas that there would be more behavioral health services with [managed care] than there were before [managed care] started . . . . People had high expectations that weren’t realistic” (Field notes, 5/5/00).

Despite these constraints, BHO administrators affirmed the ideologies of professional and market accountability, motivated in their work by the belief that they were reforming a fragmented fee-for-service system that lacked assurances of quality care for patients and cost effectiveness for payers. For example, another BHO administrator stated that her commitment to MMC was firmly grounded in these ideologies of accountability. “Working in an HMO is like working in a bank, it’s super-regulated,” she asserted, observing that both BHOs and clinicians must abide by standards defined by the state government and the National Committee on Quality Assurance, which she called “the accreditation body du jour” (Field notes, 5/23/00). Charged with the awesome tasks of expanding the capacity of mental health programs and of ensuring that providers provided quality care without bilking the system for financial gain, this BHO administrator disputed providers’ claims that the BHOs were harming the welfare of Medicaid patients by regulating the occupancy rates of residential treatment centers and thereby restricting access to needed mental health services.

The juxtaposition of the BHOs’ organizational ideologies of professional accountability against the realities of New Mexico’s health care marketplace created a contradiction for BHO administrators that can be characterized as follows: BHOs were to encourage the use of cheaper, community-based services to generate profits. The state government and MCOs, however, did not provide BHOs with the financial resources needed to develop these new services. As Morgen (2001) points out in her study of the impact of welfare-to-work policies on public employees, the implementation of welfare restructuring processes are frequently forgetful of chronic understaffing and inadequate funding for public programs, which set the scene for the emergence of such contradictions. BHO administrators solved such contradictions by blaming providers for the inadequacies of the system and attributing ulterior motives to them.

The imposition of professional and market accountability set up structural conditions that undermined possibilities for collaboration between BHO administrators and frontline service providers, who were each suspicious of the other. Yet, these conditions were less at issue than were the actions and behaviors of specific individuals, groups, and institutions. Professional accountability—through utilization review processes that required providers to obtain authorizations prior to rendering care and to obtain reauthorizations thereafter—implicitly defined providers, rather than the system, as the problem and justified the regulation of their work activities. By controlling the clinicians’ utilization of resources, BHOs were in the position to not only inculcate new ideologies and practices of professionalism, but to improve their financial performance as well.

Nevertheless, a 2000 state government assessment of the utilization review practices put in doubt whether the BHO administrators’ promises of improving care while decreasing costs were actually possible. Affirming the concerns of the very frontline service providers who had been labeled as “special interests” by state officials and BHO administrators, this state government assessment uncovered serious problems in chart documentation of BHO clinical case files, including improper denials and poor discharge planning. This report also verified that Medicaid recipients were indeed being placed in lower levels of care than their mental health conditions warranted (Medical Assistance Division 2000).

Transportation under Medicaid Managed Care

The White Sands Partial Program in Albuquerque was one of the many mental health programs that contracted with the BHOs to provide services to young Medicaid recipients, ages 4 to 17.2 White Sands was a state-accredited school and was legally obliged to provide transportation services to its young charges, most of whom received Medicaid. As a partial program, services were less intensive than those of acute inpatient and residential treatment and were more intensive than day treatment and outpatient care. Patients were not supposed to be suicidal or psychotic, but suffer from behavioral problems severe enough that they could not “normally” function in a “regular” classroom. The goal of treatment was to reintegrate the children into their home schools by providing on-site special education instruction and individual, group, and family therapy.

Within the metropolitan area of Albuquerque, patients may need to travel great distances to make their mental health care appointments. The obligation to transport Medicaid recipients to these appointments was written into the state’s Medicaid contracts. On this basis, the state allocated a fixed amount to the MCO and their BHO partners for each person enrolled in Medicaid and this amount was meant to cover costs for transportation. Because the MCOs and BHOs lacked infrastructures to provide transportation on their own, they generally contracted with low bidding cab companies to take care of the local transportation needs for the geographically dispersed population of Medicaid recipients.

Each morning, taxis lined up curbside at the entrance of White Sands, dropping off the children for class and therapy. Even though each Medicaid recipient’s capitation covered individual transportation, drivers routinely filled their taxis with multiple children on a single trip. This ride could be dangerous since some taxis lacked appropriate safety restraint mechanisms.

The children’s guardians (i.e., biological parents, therapeutic foster parents, or grandparents) claimed that the services provided by the cab companies were undependable and that patients were not returned home until late in the afternoon or early evening. One guardian who lived 15 miles away from White Sands commented: “City Taxi was terrible! Crystal would leave White Sands at 3:00 and wouldn’t get home until 6:30. The driver would drop off other passengers first. I’d have to call and ask, ‘Where is she?”’ (Field notes, 12/15/99). A second guardian criticized this same company: “City Taxi was the pits. They wouldn’t show up or showed up too late. Days on end they wouldn’t bother coming and Brianna couldn’t get to White Sands” (Field notes, 12/22/99). The children did not care much for the taxis either, with one irritated child sitting in the waiting room exclaiming, “This sucks, man. I hate my taxicab company” (Field notes, 12/15/99).

Several clinicians recognized that “there’s an inherent risk in using cabs” and acknowledged that most families on Medicaid would prefer not to count on taxis, but must because they lacked their own vehicles or gas money (Field notes, 12/17/99). There were complaints that drivers cursed and smoked in the children’s presence, allegations of drug pushing by drivers, and at least one suspected case of sexual abuse. Nonetheless, the MCOs and BHOs did not sever their ties to the cab companies and instead brokered a deal in which each young Medicaid patient could have an escort who would not be charged. This arrangement burdened guardians because the company charged for additional persons who needed to come along, such as siblings who could not be left home unattended. The White Sands staff also reported that cab rides were traumatizing for the “vulnerable” and “fragile” youngsters at White Sands (Field notes 12/6/99, 1/6/00). Teachers and mental health technicians might have to devote the first hour of the morning to calming patients who arrived in the cabs, diminishing time otherwise spent on class activities and therapy. A few clinicians expressed misgivings to the White Sands administration about the reliance on cabs, which were ignored. According to one psychiatrist, the staff felt “helpless” (Field notes, 12/28/99).

Compounding the clinicians’ perceived powerlessness was the belief that conflicts of interest existed within the White Sands administration. As an accredited school, White Sands was required to transport students and had purchased shuttles for this purpose, but these vehicles were not used to pick up or drop off children. If the White Sands administration were to use the shuttles for this, then it would have to hire staff specially trained to work with the mentally ill and obtain appropriate insurance coverage; a bonded, certified driver could cost $60,000 per year. To minimize staffing expenditures for transportation and other costs, particularly liability, some clinicians asserted that the White Sands administration chose to rely on the contractual requirement of MCOs and BHOs to provide Medicaid recipients with transportation to their mental health care appointments. The administration responded that shuttles were impracticable because patients often traveled long distances and would need to remain on the shuttles for unreasonable periods of time to accommodate the transport of fellow riders. They pointed out that White Sands used any savings it retained to support clinical personnel who filled direct service needs.

The transportation issue exemplifies how market triumphalism can prevail over professional accountability. The Medicaid system permitted the use of transportation services that were allegedly cost effective to the MCOs and BHOs, but which detracted from the consistent provision of quality mental health and education services to children. Clinicians argued that the White Sands administration did not complain vociferously to the MCOs and BHOs about inadequate cab service because these entities provided White Sands with most of its referrals, which obviously contributed to the economic survival of White Sands.

Not addressing this issue shifted blame for poor quality care downward. Some clinicians confronted with this cost-saving policy that put patients at risk reacted by blaming guardians for not providing their children with transportation, even though they knew that many guardians took unpaid leave or skipped work without employer authorization to tend to their children’s health care needs. For example, one psychiatrist suggested that the guardians of White Sands patients viewed transportation services under Medicaid as “entitlements.” Asserting that guardians “like the free ride,” the psychiatrist added, “In some ways it’s disturbing to me that they’ll let their 5-year-old drive in a cab. . . . I’d estimate that 75 percent of our parents don’t want to take responsibility for driving our kids” (Field notes, 12/28/99). Similarly, a teacher asserted, “The idea that parents bring them here every morning is a joke. With 90 percent of the kids, their parents are the common denominator. They need more parenting skills” (Field notes, 12/20/99).

The staff at White Sands contrasted the family situation of Medicaid clients with that of non-Medicaid clients, observing that the guardians of the privately insured children were typically “middle class” and “on the ball” (Field notes 12/17/99; 3/20/00). Although recognizing that the middle-class guardians were able to access reliable transportation, the staff also perceived them as willing to transport their children to White Sands. Furthermore, these guardians were praised for their active involvement in the children’s treatment, including regular participation in family therapy and the program’s structured family activities. In contrast, the guardians of Medicaid recipients were often criticized for their lack of involvement in the treatment of their children.

Making assumptions about who is responsible for a patient’s situation can enable frontline service providers to distance themselves from persons under their care (Lipsky 1980). This tendency to “blame the victim,” or in this case, guardians, absolved the clinicians at White Sands from culpability for their own perceived inability to assure the delivery of professionally accountable services. As Lipsky (1980) had argued in his seminal study of street-level bureaucrats, victim-blaming views are often adopted by providers who feel powerless, confronted with the contradiction that they should be making a difference in clients’ lives but often cannot because of factors that seem out of their control. Building on Lipsky’s argument, Kingfisher (1996 Kingfisher (2001) clarified how welfare workers in Michigan contended with large caseloads, diminished autonomy, and unrealistic expectations regarding the outcome of their work with clients, much like the White Sands clinicians. These workers were also located on the bottom rung of an increasingly complex bureaucratic hierarchy, possessing little formal power within the institution in which they worked. In the context of proliferating policy restrictions regulating their workaday interactions, they, too, invoked negative constructions of the characters of clients to accommodate the idea that clients were to blame for the situations in which they found themselves.

Although enabling frontline service providers to explain away their own possible failures and those of the agencies for which they work, victim-blaming views also allow them to displace responsibility onto clients, diverting it from the organizational systems of which they are a part and in which they are ultimately complicit. As a result, this displacement permits the providers “to develop more comfortable relations with the contradictions in their work” (Lipsky 1980:154).

At White Sands, these contradictions and the ambivalence they engender were exacerbated by the clash between the time-honored trust relationship between provider and patient that derived from the Hippocratic tradition and the newer, profit-oriented models of professional and market accountability favored under managed care. By pointing the finger at guardians for not attending to the travel needs of kin, accountability in provider–patient relationships shifted away from clinicians toward families. Such deflection, moreover, was emblematic of how these models ultimately facilitate the devolvement of responsibility for service provision to the personal domain of the individual and the family, away from the state and its corporate partners (Clarke 2004; Clarke and Newman 1997).

Although clinicians at White Sands could (and often did) encourage guardians to pursue grievances or legal action to ensure that required services under Medicaid were in place, this type of advocacy placed an extra burden on the clinicians because many guardians could not navigate these complex processes on their own. By abdicating responsibility, the clinicians instead rationalized their disappointment with particular guardians and thereby justified why they could not meet their obligations to provide quality care for all patients. They faulted economically disadvantaged guardians who worked long hours and, thus, were not seen by the White Sand’s staff as being very involved in their children’s care. Regardless of whether the clinicians advocated for Medicaid patients or blamed them for their problematic situations or even for their lack of success in treatment, the clinicians’ energies were focused on persons possessing the least amount of formal power and authority to compel changes in the Medicaid system.

Although transportation is not typically seen as a required component of quality care, I suggest that in meeting their state-mandated obligation to transport Medicaid recipients to mental health appointments, the MCOs and BHOs have entered into contractual arrangements with cab companies that compromise the provision of quality mental health services. Given the strict models of professional accountability required under managed care, one would expect facilities like White Sands to blow the whistle on these contractual arrangements, specifically targeting those cab companies that load their taxis with as many as seven unbuckled children per trip. Notably, measures used by the state Medicaid agency to assess MCO and BHO performance focused neither on the safety factors nor the timeliness of transportation services for Medicaid recipients. Such measures would make it easier to advocate for better transportation services.

In any case, conflicts of interest engendered by MMC dissuade provider organizations and clinicians from mounting opposition to such contractual arrangements. Although the clinicians believed taxi travel was unsafe and worsened the acuity level of patients, they feared retribution from the White Sands administration, which considered it to the program’s advantage to rely on transportation offered under MMC. If the administration pressed for enhanced transportation services, it jeopardized its own financial relations with the BHOs, the main source of patient referrals for White Sands. The unequal balance of bargaining power, the drive to demonstrate profits, and the resulting conflicts of interest ensured that the BHOs experienced little pressure to improve transportation services or, for that matter, clinical care for Medicaid recipients.

Conclusion

The downward transfer of blame pervades the new MMC hierarchy. I examined the single issue of transportation under this system to trace the consequences of market triumphalism eclipsing market and professional accountability. In this example, the interplay between managed care’s emphasis on cost-savings policies and the clinicians’ concerns regarding eroding trust relationships with patients resulted in a catch-22, the outcome of which was to scapegoat Medicaid recipients and their families. In the example of residential treatment, BHOs and state officials used arguments regarding professional standards to cover the bottom line—profit. These arguments furthered the move away from residential treatment to community-based services under MMC. Although BHO administrators were charged with developing these services, they were unable to do so because of financial constraints. Yet, they proceeded to restrict authorizations for existing services and fault providers for the inadequate mental health care infrastructure in New Mexico and for their resistance to Medicaid reform. Finally, in the example of the public–private “partnership,” once again those with greater authority and power—state officials—blamed providers for deficiencies in the Medicaid system.

Models of professional and market accountability create contradictions for all players in the hierarchically arranged Medicaid system. For providers, the formidability of settling these contradictions discourages protest of unfair policies and impedes better patient care. BHO administrators are compromised as they espouse managed care’s ideology of cost effectiveness in an already limited medical environment. Meanwhile, the interest of state officials in downsizing the state’s role in caring for the poor and forging nonconflictive partnerships with managed care companies constrain its ability to advocate for patients and providers. The inverted power dynamics of this partnership also weaken the state’s ability to leverage performance improvement from managed care entities and to ensure that Medicaid recipients can access medically necessary services.

I have sought to expose the power differentials underlying the nested hierarchies of the MMC system, power asymmetries that have been hidden from view by models of professional and market accountability. It is ironic that while accountability models purport to delineate chains of authority, in practice these models shift the responsibility to the most powerless (to providers and to patients and away from the authorities that created them). The appeal of accountability derives from the assumption of responsibility by authoritative individuals, but, as the discussion of state officials’ reluctance to criticize the managed delivery of mental health services illustrates, these individuals tend to be the least forthcoming when theoretical ideas are implemented.

The structures through which frontline service providers and Medicaid clients must interact to obtain care are loaded in favor of the MCOs and their BHO contractors. The seeming indifference of state officials and BHO administrators to the plight of Medicaid recipients is in keeping with the aggressive promotion of devolution, contracting, and privatization by the political and corporate elite. Constructing providers and Medicaid recipients as the objects of scrutiny, models of professional and market accountability are embedded in the corporate managerialism that continues to be promoted by neoliberals as the universal solution to the problem of improving public services (Clarke 2004).

Ideologies and practices of managerialism were intended to provide New Mexico’s Medicaid program with the discipline needed to ensure the delivery of efficient, cost effective, and professional services. Despite emphasizing accountability, these ideologies and practices have led to the proliferation of entities participating in policy making and service delivery, resulting in the expansion of “authorized” decision-making sites (Clarke 2004:123) where contestation over the definition and enactment of professionalism and interorganizational battles over scarce resources and profits are rampant. Buck passing and even deception persist as the modus operandi of the state bureaucratic system (Gupta 1995; Herzfeld 1992), especially because the individuals authorized to present the “facts” of performance are prone to suppress information regarding the Medicaid program’s possible failures. As seen in New Mexico’s attempt to delegate state responsibility for its Medicaid mental health care program to the private sector, the imposition of corporate professional and market accountability models has not resulted in transparent processes for operating the program, despite repeated efforts to impart this impression. Rather, these models appear to conceal patterns of systemic dysfunction, thwarting concern for how the push for profit surmounts the desire for quality care for Medicaid recipients.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1R01 HS09703), the National Institute of Mental Health (1R03 MH6556), the UNM Division of Community Medicine, and the New Mexico Department of Health.

I thank the anonymous reviewers, Louise Lamphere, Adriana Greci Green, Sarah Horton, Nancy Nelson, Ann Carson, and Rafael Semansky for their comments on a previous version of this article, and Howard Waitzkin and William Wagner who contributed greatly to this research.

Footnotes

William Wagner and I carried out the fieldwork on which this article is based between November 1999 and August 2000, focusing on Medicaid managed care’s impact on mental health services. We conducted observations at public Medicaid forums and mental health facilities, including 4 months of fieldwork at the White Sands Partial Program, described later in this article. We conducted 65 in-depth interviews with frontline service providers, patients, BHO administrators, and state officials. This work was supplemented by interviews with MCO administrators and state officials undertaken by Howard Waitzkin, the study’s principal investigator, in 2002. More information regarding our overall methodology is in a separate article (Willging, Waitzkin, Wagner 2004).

Pseudonyms are used when referring to people, places, and companies.

References

- Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law 2000 Failing to Deliver: Analysis of New Mexico Medical Assistance Division. Data on Salud! Behavioral Health Care. Washington, DC: Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law.

- Clarke, John 2004 Changing Welfare, Changing States: New Directions in Social Policy. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Clarke, John and Janet Newman 1997 The Managerial State: Power, Politics and Ideology in the Remaking of Social Welfare. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Daniels Norman, James Sabin. The Ethics of Accountability in Managed Care Reform. Health Affairs. 1998;17(3):50–64. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.17.5.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donald Alistair. The Wal-Marting of American Psychiatry: An Ethnography of Psychiatric Practice in the Late 20th Century. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 2001;25(4):427–439. doi: 10.1023/a:1013063216716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson Molla S. Accountability for Quality in Managed Care. Journal on Quality Improvement. 1998;24(12):711–725. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30417-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossett, James W., Malcom Goggin, John S. Hall, Jocelyn Johnston, Christopher Plein, Richard Roper, and Carol Weissert 1999 Managing Accountability in Medicaid Managed Care: The Politics of Public Management. Albany, NY: The Nelson A. Rockefeller Institute of Government.

- Goode, Judith, and Jeff Maskovsky, eds. 2001 New Poverty Studies: The Ethnography of Power, Politics, and Impoverished People in the United States. New York: New York University Press.

- Gupta Akhil. Blurred Boundaries: The Discourse of Corruption, the Culture of Politics, and the Imagined State. American Ethnologist. 1995;22(2):375–402. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon, Michael M. 1995 Responsibility as Paradox: A Critique of Rational Discourse on Government. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Herzfeld, Michael 1992 The Social Production of Indifference: Exploring the Symbolic Roots of Western Bureaucracy. New York: Berg.

- Kingfisher, Catherine Pélissier 1996 Women in the American Welfare Trap. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- ——— 2001 Producing Disunity: The Constraints and Incitements of Welfare Work. In The New Poverty Studies: The Ethnography of Power, Politics, and Impoverished People in the United States. Judith Goode and Jeff Maskovsky, eds. Pp. 273–292. New York: New York University Press.

- Legislative Finance Committee 2000a Audit of Medicaid Managed Care Program (SALUD!) Cost Effectiveness. Santa Fe: State of New Mexico.

- ——— 2000b Audit of Medicaid Managed Care Program (SALUD!) Cost Effectiveness and Monitoring. Santa Fe: State of New Mexico.

- Light, Donald 2000 The Medical Profession and Organizational Change: From Professional Dominance to Countervailing Power. In Handbook of Medical Sociology, 5th ed. Chloe E. Bird, Peter Conrad, and Allen M. Fremont, eds. Pp. 201–216. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Lipsky, Michael 1980 Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Lofland, Jennifer H., and David B. Nash 2001 Academic Health Centers and Managed Care. In The Managed Health Care Handbook, 4th ed. Peter R. Kongstvedt, ed. Pp. 206–227. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen.

- Maskovsky Jeff. “Managing” the Poor: Neoliberalism, Medicaid HMOs, and the Triumph of Consumerism among the Poor”. Medical Anthropology. 2000;19(2):121–146. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2000.9966173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medical Assistance Division 2000 Salud! On-Site Program Integrity Review. Santa Fe: State of New Mexico.

- Morgen Sandra. The Agency of Welfare Workers: Negotiating Devolution, Privatization, and the Meaning of Self-Sufficiency. American Anthropologist. 2001;103(3):747–761. [Google Scholar]

- Morgen Sandra, Jeff Maskovsky. The Anthropology of Welfare “Reform”: New Perspectives on U.S. Urban Poverty in the Post-Welfare Era. Annual Review of Anthropology. 2003;32:315–338. [Google Scholar]

- Rylko-Bauer Barbara, Paul Farmer. Managed Care or Managed Inequality? A Call for Critiques of Market-Based Medicine. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2002;16:476–502. doi: 10.1525/maq.2002.16.4.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberman Pam, Stephanie Poley, Kerry James, Rebecca Slifkin. Tracking Medicaid Managed Care in Rural Communities: A Fifty-State Follow-Up. Health Affairs. 2002;21(4):255–263. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.4.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- William M. Mercer, Inc. 2000 Salud! Medicaid Managed Care: Behavioral Health Funding: State Fiscal Years 1998 and 1999. Phoenix: William M. Mercer, Inc.

- Willging, Cathleen, Howard Waitzkin, and William Wagner 2004 The Death and Resurrection of Medicaid Managed Care for Mental Health Services in New Mexico. In Unhealthy Health Policy: A Critical Anthropological Examination. Arturo Castro and Merril Singer, eds. Pp. 247–256. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira.