SUMMARY

The murine Dlx3 protein is a putative transcriptional activator that has been implicated during development and differentiation of epithelial tissue. Dlx3 contains a homeodomain and mutational analysis has revealed two regions, one N-terminal and one C-terminal to the homeodomain, that act as transcriptional activators in a yeast one-hybrid assay. In addition to transactivation, data are presented to demonstrate specific DNA binding and an association between Dlx3 and the Msx1 protein in vitro. Immunohistochemical analysis confirmed coexpression of Dlx3 and Msx1 proteins in the differentiated layers of murine epidermal tissues.

Transcription factor function requires nuclear localization. In this study, the intracellular localization of the green fluorescent protein fused to Dlx3 was examined in keratinocytes induced to differentiate by calcium and is shown to localize to the nucleus. A bipartite nuclear localization signal (NLS) was identified by mutational analysis and shown to be sufficient for nuclear localization. This was demonstrated by insertion of the Dlx3 bipartite NLS sequence into a cytoplasmic fusion protein, GFP-keratin 14, which functionally redirected GFP-keratin 14 expression to the nucleus. Further analysis of Dlx3 NLS mutants revealed that the Dlx3 NLS sequences are required for specific DNA binding, transactivation potential and interactions with the Msx1 protein.

Keywords: Dlx3, Homeodomain, Transactivation, DNA binding, Bipartite nuclear localization signal

INTRODUCTION

The Distal-less gene family (Dlx) encodes transcriptional regulators that contain a homeodomain and have been suggested to play a role in developmental differentiation (Anderson et al., 1997; Bendall and Abate-Shen, 2000; Morasso et al., 1996; Qiu et al., 1997). The Dlx genes are organized into pairs of closely linked, convergently transcribed loci located in close proximity to one of the four Hox clusters in the mouse genome. The Dlx genes are expressed in distinct but overlapping domains, primarily in the forebrain, brachial arches and tissues derived from epithelial-mesenchymal interactions (Bendall and Abate-Shen, 2000; Qiu et al., 1997; Robinson and Mahon, 1994).

Murine Dlx3 transcripts have been detected in hair follicles, tooth germ, mammary gland primordium, brachial arches, limb buds, and in the suprabasal keratinocyte compartment of the interfollicular epidermis (Morasso et al., 1995; Morasso et al., 1996; Robinson and Mahon, 1994). Ectopic expression of Dlx3 in transgenic animals strongly supports the hypothesis that Dlx3 has a role in the regulation of differentiation-specific genes in the stratified epithelium (Morasso et al., 1996). During epidermal differentiation, mitotically active basal keratinocytes cease to proliferate, detach from the basement membrane and migrate through the spinous and granular layers. The differentiation process from a basal cell to a terminally differentiated cornified epithelial cell is associated with a stepwise program of transcriptional regulation with sequential induction and repression of structural and enzymatic differentiation-specific markers (Eckert and Welter, 1996; Fuchs and Byrne, 1994). This process can be achieved in primary mouse keratinocytes cultured in vitro by increasing the calcium (Ca2+) concentration in the medium to mimic the endogenous Ca2+ gradient present in epithelium (Hennings et al., 1980; Yuspa et al., 1989). The specific role that Dlx3 plays in development and differentiation is presently unclear. However, the presence of functional Dlx3 is essential since ablation of the Dlx3 gene in transgenic mice resulted in embryonic lethality at day 9.5 (Morasso et al., 1999). Furthermore, a deletion resulting in a frameshift/truncation mutation of DLX3 has been associated with the human autosomal dominant disorder Tricho-Dento-Osseous (TDO) syndrome (Price et al., 1998).

Murine Dlx3 is a 287 amino acid (aa) protein with the homeodomain located between 130–189 aa. The homeodomain is a highly conserved 60 aa stretch responsible for sequence-specific interactions with DNA (Catron et al., 1993; Gehring et al., 1994a; Gehring et al., 1994b). The binding sites of homeodomain proteins typically center around TAAT sequence motifs and the adjacent bases are thought to impart specificity to interactions between homeodomain factors and target genes (Laughon, 1991; Scott et al., 1989). Structurally, the homeodomain is composed of an N-terminal arm followed by three short α-helices. The third and most C-terminal helix has been implicated in direct binding in the major groove of DNA (Billeter et al., 1993; Kissinger et al., 1990). A consensus DNA binding site for the Xenopus Dlx3 protein has been recently described (Feledy et al., 1999) as TAATT with the adjacent adenine 5′ and guanine and cytosine bases 3′, enhancing binding specificity. The Xenopus and murine Dlx3 proteins have 62% identity; however, their homeodomain sequences are 100% identical.

The Msx protein family members are the closest related homeodomain proteins to Dlx. While Dlx proteins have been shown to be transcriptional activators, Msx proteins function as transcriptional repressors (Davidson, 1995; Feledy et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 1996; Zhang et al., 1997). The Msx1 protein is capable of binding a TAAT-containing DNA sequence. However, Msx1 does not need to bind DNA to functionally repress transcription. In the absence of DNA binding, an association between Msx1 and a TATA-binding protein is essential for Msx1 repressive function (Catron et al., 1995). It has been proposed that heterodimerization of Dlx and Msx protein family members will abrogate both Dlx and Msx function. Zhang et al. (1997) have presented evidence demonstrating that heterodimerization of Msx1 or Msx2 with Dlx2 or Dlx5 proteins results in functional antagonism and a loss of binding to both DNA and TATA-binding protein. Associations between other Dlx and Msx family members and the high homeodomain sequence identity between Dlx2, Dlx3 and Dlx5 suggests a likelihood of Dlx3 associations with an Msx family member. The functional characteristics of the murine Dlx3 protein in transactivation, DNA binding and interaction with the Msx1 protein are addressed in this study.

An essential step for transcription factor function is nuclear localization. Proteins that travel between the cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments of the cell pass through the nuclear membrane by way of the nuclear pore complex (NPC) (Dingwall and Laskey, 1991; Imamoto et al., 1998; Izaurralde and Adam, 1998; Jans and Hassan, 1998). A protein to be transported must contain a nuclear localization signal (NLS). Single and bipartite NLS sequences have been identified. The single NLS has been described as a cluster of 3–5 basic residues, with the SV40 large T antigen NLS recognized as the prototype sequence, PKKKRKV (Dingwall and Laskey, 1991). The bipartite NLS is composed of a few basic residues separated from a second cluster of basic residues by 10–16 aa. The intervening sequences are thought to impart a tertiary structure, which will allow the two basic clusters to be spatially accessible to nuclear transport molecules (Dingwall and Laskey, 1991).

In this study we examined Dlx3 protein expression and function. Dlx3 transactivation potential was established in a yeast one-hybrid assay in the absence of direct DNA binding. Specific DNA binding was demonstrated in competition gel-mobility shift assays. In addition to DNA binding, Dlx3 was shown to interact with the Msx1 transcriptional repressor protein, and immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated coexpression of Dlx3 and Msx1 proteins in vivo. Fluorescence microscopy of transiently transfected primary keratinocytes revealed that GFP-Dlx3 (green fluorescent protein-Dlx3 fusion) localized to the nucleus. We present data identifying a bipartite NLS sufficient for nuclear localization. NLS mutational analysis correlated with loss of Dlx3 function. Therefore, we conclude that the Dlx3 NLS sequence and/or sequence position within the protein can direct protein localization, and is also required to maintain Dlx3 transcription factor function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction

The yeast vector pGBT9 (Clontech), which contains the GAL4 DNA binding domain (GAL4 BD), was used to create GAL4 BD-Dlx3 fusion proteins. Dlx3 and Dlx3 5′ and 3′ truncation mutants were amplified by PCR. In all cases, AmpliTaq polymerase (Perkin Elmer) was used in the PCR amplification and the resulting PCR product cloned directly into pCR2.1 by TA cloning (Invitrogen). The Dlx3 sequences were then excised by specific restriction endonuclease digestion and cloned in-frame into pGBT9. DNA sequence analysis was performed to confirm the Dlx3 sequence with introduced mutations.

To create Msx1 encoding plasmids, Msx1 transcripts were isolated from differentiated keratinocytes and converted to cDNA. Primary mouse keratinocytes were isolated from the skins of 1–2 day Balb/c pups (Hennings et al., 1980; Yuspa et al., 1989). The suprabasal cells were separated from the basal cell population by continuous Percoll gradient (Lichti and Yuspa, 1988). Total RNA was isolated from the suprabasal cells by the Trizol method as described by the manufacturer (Life Technologies Gibco BRL). Poly(A)+ RNA was obtained by passing total RNA through an oligo-dT column and eluting as directed by Clontech. Poly(A)+ RNA was then converted to cDNA using oligo-dT and random hexamer primers, MMLV reverse transcriptase for the first strand synthesis and an enzyme cocktail of E. coli DNA polymerase, RNase H and E. coli DNA ligase followed by T4 DNA polymerase for the second strand synthesis (Clontech). Msx1 sequences were amplified from the suprabasal cDNA using 5′ MSX1-Bam GGG ATC CTC ATG ACT TCT TTG CCA CTC GGT and 3′ MSX1 GGC TAG GAA GGA CTC CCG CTG CTC C oligonucleotides in a PCR regime of 94°C, 1 minute denature, 55°C, 1 minute anneal and 72°C, 1 minute extension for 30 cycles, using AmpliTaq polymerase. Amplified Msx1 sequences were cloned into pGEX-3x (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Inc.) and in-frame cloning confirmed by sequencing.

The pEGFP-C1 vector (Clontech) was employed to create GFP fusion proteins with Dlx3 driven by the CMV IE promoter (GenBank U55763). Dlx3 5′ and 3′ truncation mutations were created utilizing restriction endonuclease sites and PCR amplification. The internal Dlx3 restriction endonuclease sites, BamHI at bp 267, PstI at bp 435 and KpnI at bp 756, were first used to create large deletion mutants. A series of internal oligonucleotide primers were then designed to amplify and clone more specific regions of the Dlx3 gene. Likewise, substitution mutations were created by PCR using oligonucleotide primers containing point mutations to alter the coding sequence of a specific aa residue. Wild-type sequences were replaced with amplified mutated sequences by restriction endonuclease cloning to create the mutants illustrated in Fig. 6. DNA sequence analysis was performed to confirm all mutations and in-frame cloning with GFP.

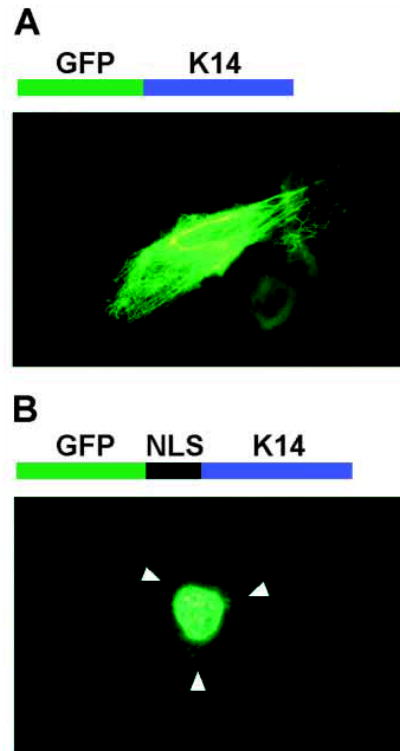

Fig. 6.

Fluorescence microscopy demonstrating that the Dlx3 NLS is sufficient for nuclear localization. (A) Above the photomicrograph is a schematic representation of the GFP-K14 fusion protein. Below is a direct fluorescence micrograph of a primary murine keratinocyte transiently transfected with pEGFP-C1-K14 and grown for 24 hours in medium containing 0.12 mM Ca2+. (B) Above the photomicrograph is a schematic representation of GFP fused in-framed with the Dlx3 NLS (124–150 aa) fused in-frame with K14. Below is a direct fluorescence micrograph of a primary murine keratinocyte transiently transfected with pEGFP-C1-NLS-K14 and grown for 24 hours in medium containing 0.12 mM Ca2+. Arrowheads indicate the location of the cell membrane.

Cell culture and transfection

Primary mouse keratinocytes were obtained as described by Hennings et al. (1980) and Yuspa et al. (1989). Cells were plated in EMEM plus 8% chelated fetal bovine serum (FBS) with 0.05 mM Ca2+ on glass coverslips. Ca2+ concentration was determined by atomic absorption spectrophotometer analysis. After 24 hours, the cells were transfected with 1 μg of plasmid DNA per coverslip with 3 μg Lipofectin, as described by the manufacturer (Life Technologies Gibco BRL). After 4 hours the mix was aspirated and 1 ml of 15% glycerol in Keratinocyte-SFM (Life Technologies Gibco BRL) was applied for 3.5 minutes. The glycerol solution was replaced with 2 ml of fresh medium with 0.05, 0.12 or 1.4 mM Ca2+, after which the cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 24 hours. The coverslips were recovered, washed in 1× PBS and treated with DAPI counterstain to identify nuclei. The coverslips were washed in 1× PBS and mounted onto glass slides with Gel/Mount (Biomeda Corp.). Intracellular localization of GFP fusion proteins was determined by direct fluorescence microscopy. Dlx3 mutant protein expression was confirmed by anti-GFP (Clontech) immunoblot analysis of extracts made from transiently transfected cells (data not shown).

Yeast transformation and one-hybrid Dlx3 transactivation

HF7c Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Clontech) were cultured on YPD plates for 4 days at 30°C. The cells were made competent by the lithium acetate method and transformed by the PEG/lithium acetate method, as described by Clontech. HF7c cells were transformed with 100 ng of pGBT9, pGBT9-Dlx3 or pGBT9-mutated Dlx3 plasmid DNA, plated on CSM(−)Trp (complete synthetic medium without tryptophan, Bio 101) and incubated at 30°C for 3–5 days. The transactivation potential of a given GAL4 BD-Dlx3 fusion protein was assayed by a liquid culture β-galactosidase assay. 3 ml of CSM(−)Trp medium were inoculated with 1–2 colonies of transformed HF7c cells and incubated at 30°C with shaking at 200 rpm for 24 hours. 4 ml of YPD medium were added to each culture and incubation continued for 3–5 hours. The OD600 was recorded and the liquid culture β-galactosidase assay performed as described by Clontech. The total time of the reaction was recorded in minutes. Upon terminating the reaction with Na2CO3, the OD420 was determined by spectrophotometry. The β-galactosidase units for each transformed HF7c culture, an indirect measure of transactivation potential, were calculated by applying the formula: OD420×1000/t×V×OD600=β-galactosidase units, where t is time of reaction in minutes and V is the volume of cells used in ml. Each culture was assayed in duplicate and each GAL4 BD-Dlx3 fusion protein was assessed in a minimum of three separate experiments.

Preparation of recombinant proteins

The full open reading frame of the murine Dlx3 gene was cloned into the bacterial expression vector pET 28a (Novagen), generating a hexahistidine fusion protein with a T7-epitope tag. In a similar manner, wild-type Dlx3 DNA sequences encoding the first 252 aa and mutated Dlx3 DNA sequences were cloned into pET 28a to generate hexahistidine fusion proteins. 10 ml of LB plus 50 μg/ml kanamycin were inoculated with transformed BL21 (DE3) cells (Novagen) and grown for 16 hours at 37°C with shaking. The cells were subcultured in 100 ml LB plus kanamycin and grown to an OD600 of 0.6 before induction. Following the 3 hour induction with isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside, the hexahistidine fusion proteins were purified from lysates by nickel affinity column chromatography using the Ni-TA system under native conditions, as directed by the manufacturer (Qiagen). Immunoblot analysis was performed to confirm expression of the Dlx3 and Dlx3 mutant proteins. Proteins were separated by 4%–20% gradient SDS-PAGE, and western-transferred to nitrocellulose. The blot was blocked with 2.5% non-fat dry milk in TBS-T (20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 37 mM NaCl and 0.1% Tween-20). Antibodies were applied for 4 hours at room temperature, the blot was washed with TBS-T and immune complexes detected by NBT-BCIP substrate.

The full open reading frame of the Msx1 gene was cloned into the bacterial expression vector pGEX-3x and transformed into XL1-Blue cells (Stratagene). A 100 ml culture was grown to OD600 of 0.6 and isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside induced to express the GST-Msx1 fusion protein. GST-Msx1 was purified by binding to Glutathione-Sepharose 4B resin as described by Pharmacia. Immunoblot analysis was performed to confirm specific GST-Msx1 protein expression (data not shown).

Gel mobility-shift assays

The Dlx3 consensus binding site, underlined (Feledy et al., 1999) was produced as complementary 25 bp oligonucleotides with EcoRI and BamHI extensions (CGG GAT CCA TAATT GC TGG AAT TCC). Likewise a mutated Dlx3 consensus-binding site, in which the AATT was replaced with GGCC, was produced with EcoRI and BamHI extensions. The Msx1 consensus binding site oligonucleotides (Catron et al., 1993) were a kind gift from the laboratory of Dr Thomas Sargent (NIH, NICHD) (GGG GGG GC TAATT GG GGG GG). The binding site sequences were synthesized as complementary oligonucleotides, and annealed at a concentration of 200 ng/μl. Dlx3 double-stranded (ds) consensus binding site oligonucleotides were end-labeled with [γ-32P]-ATP using the Ready-to-Go PNK kit, as described by the manufacturer (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Inc.). The Dlx3 consensus binding site probe DNA was loaded on an 8% TBE-polyacrylamide gel and electrophoresed in 0.5× TBE. The radiolabeled probe DNA was localized by autoradiography, excised from the gel, and eluted for 16 hours in 0.5 M ammonium acetate, 10 mM magnesium acetate, 0.12% SDS and 1 mM EDTA at 50°C with agitation. The eluted probe DNA was precipitated with ethanol and suspended in 40 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 10 mM NaCl, 1 mM Mg Cl2, 1 mM EDTA and 10 mM DTT.

Gel mobility-shift assays were performed by incubating 7 ng of recombinant Dlx3 or mutated Dlx3 protein with 80,000 cpm purified radiolabeled Dlx3 probe DNA in a 20 μl reaction containing 7 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 81 mM NaCl, 112.5 mM imidazole (from recombinant protein elution buffer), 2.75 mM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.05% NP-40, 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 25 μg/ml poly(dI-dC) and 10% glycerol, on ice for 30 minutes. The protein-DNA complexes were electrophoresed on a 6% DNA retardation gel in 0.5% TBE at 4°C with 10 V/cm. After electrophoresis, the gels were dried and autoradiography performed. Competition mobility-shift assays were performed with 100-fold excess Dlx3 DNA consensus binding site, mutated Dlx3 consensus binding site and Msx1 consensus binding site ds oligonucleotides as unlabeled competitor DNA.

Antibodies

Rabbit anti-Dlx3 polyclonal antiserum was generated for our laboratory by BAbCO (Berkeley Antibody Company), against a 16-mer synthetic peptide containing amino acids 242–256 of the murine Dlx3 protein. IgG anti-Dlx3 antibodies were obtained by running the polyclonal antiserum through a Protein A column, washing and eluting with a change in pH and salt concentration as directed by Pierce (ImmunoPure IgG Purification Kit). Anti-Dlx3 was used at a 1:400 dilution for immunoblot analysis and 1:500 for immunohistochemistry. Rabbit anti-Msx1 polyclonal serum generated against full-length Msx1 was purchased from BAbCO and used in immunoblot analysis at a 1:2000 dilution (1:1000 in immunohistochemistry). Rabbit anti-GST polyclonal IgG was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology and used at a 1:1000 dilution for immunoblot analysis. Phosphatase-labeled anti-T7 epitope was purchased from Novagen and used at a 1:5000 dilution. The secondary antibody used for immunoblot analysis was phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG purchased from Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories.

Dlx3:Msx1 protein pull-down assays

The Dlx3:Msx1 protein pull-down assays were performed as GST interaction assays described by Zhang et al. (Zhang et al., 1996). Resin-bound GST-Msx1 or GST were combined with the bait protein, hexahistidine-Dlx3, Dlx3 1-252 aa and mutated Dlx3 NLS sequence proteins in buffer A (20 mM Tris, pH 7.9, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.1 M NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.2% NP-40). After incubation for 1 hour at 4°C, protein-bound resin was collected by centrifugation, washed three times with buffer A containing 0.4% NP-40 and proteins eluted by incubation at 95°C for 5 minutes in SDS-sample buffer. Proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblot analysis performed using IgG anti-Dlx3 antibodies. Pulled-down Dlx3 immune complexes were detected by phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG and NBT-BCIP substrate.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed on paraffin-embedded 8 μm sections of murine neonatal stratified epithelial tissue, and 4 μm sections of adult murine epithelium from trunk, whisker pad and ear. The sections were deparaffinized and treated with Antigen Retrieval Citra as directed in the Microwave Calibration Protocol described by the manufacturer (BioGenex). The sections were washed with water and treated for 5 minutes with 0.1% trypsin in 0.1% calcium chloride and 20 mM Tris, pH 7.8. The Vectastain ABC kit was then used as described by the manufacturer (Vector Laboratories) to identify Dlx3 or Msx1 protein. Pre-immune rabbit serum was used as a negative control. Immune complexes were identified by purple Vector-VIP staining.

RESULTS

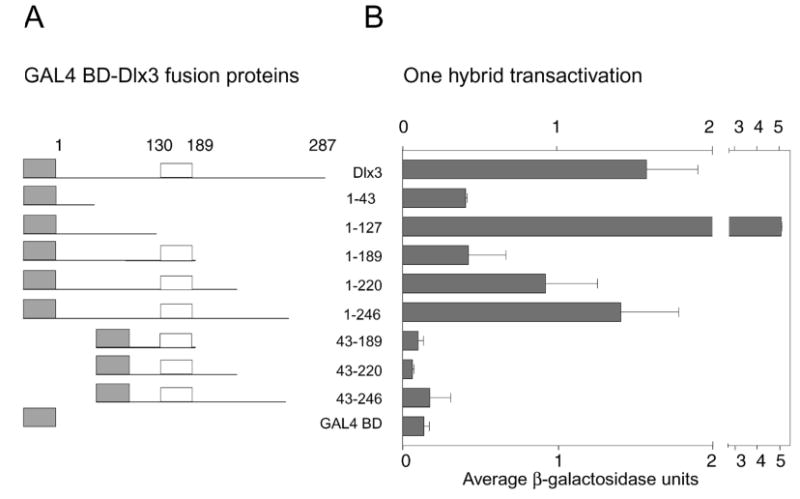

One-hybrid transactivation

To determine the transactivation potential of the murine Dlx3 protein, a yeast one-hybrid assay was performed. This system allows the transactivation potential of a given protein to be determined by quantitating the enzymatic activity of the transactivated lacZ gene. The system is designed to test transactivation potential independently of direct DNA binding. Transactivation of Dlx3 peptides fused to the GAL4 BD was determined by a liquid culture β-galactosidase assay. Mean β-galactosidase units ± s.d. of three independent experiments, each performed in duplicate, are presented in Fig. 1. The error bars depict the variation in yeast competence and transformation efficiency between individual experiments. Consistent with the findings of other homeodomain proteins (Feledy et al., 1999; Ghaffari et al., 1997), two regions of the Dlx3 protein were identified as necessary for transactivation. Deletion of the region aa 1–43 at the N terminus or the region just C-terminal to the homeodomain between aa 189 and 220 significantly decreased the transactivation potential. The first 43 aa supported transactivation to a level similar to that achieved with the first 189 aa, the complete N-terminal region and the homeodomain. It was interesting to note that the complete N-terminal region without the homeodomain, 1–127 aa, transactivated approximately threefold higher than full-length Dlx3 and tenfold higher than the N-terminal region plus the homeodomain (1–189 aa). Deleting 41 aa from the C terminus (1–246 aa) had a limited effect, whereas deleting 67 aa (1–220 aa) reduced the transactivation potential to approximately two-thirds that of the full-length Dlx3 protein (287 aa). Truncating the protein to the N-terminal region plus the homeodomain (1–189 aa) reduced the transactivation potential by an additional third. The importance of the first 43 aa was evident, as the concurrent 1–43 aa and C-terminal deletions (43–220 aa) dropped the transactivation potential down to background levels.

Fig. 1.

Transactivation potential of Dlx3 and mutated Dlx3 proteins determined by a yeast one-hybrid assay. (A) The GAL4 BD-Dlx3 and GAL4 BD-deletion Dlx3 fusion proteins. The gray boxes represent the GAL4 BD, the white boxes indicate the homeodomain region and the lines represent Dlx3 or truncations of the Dlx3 protein, which correspond to the amino acid numbers indicate on the right. (B) Mean results of three one-hybrid experiments. Each culture was tested in duplicate in the liquid culture β-galactosidase assay. The pattern of transactivation of mutant Dlx3 proteins compared to wild-type Dlx3 was reproducible. β-galactosidase units are an indirect measure of transactivation potential. β-galactosidase units were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Mean β-galactosidase units ± s.d. are recorded on the x-axis. GAL4 BD-Dlx3 fusion proteins are recorded on the y-axis. GAL4 BD alone is included to indicate the level of background transactivation in the assay.

Dlx3 and Msx1 proteins

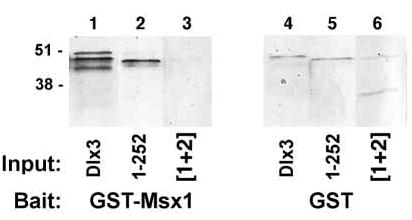

The Msx1 protein was cloned from suprabasal primary murine keratinocytes that compose the cell population in which Dlx3 is expressed (Morasso et al., 1996). Msx1 was sequenced and found to contain two silent substitution mutations but was otherwise identical to the original Hox 7 sequence (Original Msx1 designation: Accession #X59251) (Hill et al., 1989). This data provides evidence that Dlx3 and Msx1 are expressed in the same cells and thus suggests the possibility of a Dlx3 and Msx1 protein:protein interaction in vivo. An in vitro pull-down interaction assay was performed as described by Zhang et al. (1997) using bait, GST-Msx1 or GST bound to Glutathione-Sepharose 4B resin, and 200 ng of hexahistidine-Dlx3 proteins as prey. Immunoblot analysis revealed that Dlx3 was efficiently pulled-down by the GST-Msx1 fusion protein with just a trace of protein detected in the GST pull-down lane (Fig. 2, lanes 1,4). Likewise, truncated Dlx3 1–252 aa was efficiently pulled-down by the GST-Msx1 fusion protein when compared to the GST pull-down lane (Fig. 2, lanes 2,5). These data support the potential binding of Dlx3 and Msx1 proteins.

Fig. 2.

Immunoblot of GST-Msx1:Dlx3 pull-down assay. Glutathione-Sepharose 4B resin-bound GST and GST-Msx1 proteins were incubated with Dlx3 proteins. The Msx1:Dlx3 protein complexes were recovered by centrifugation. Immunoblot analysis was performed using IgG anti-Dlx3 antibody at 1:400 dilution to detect Dlx3 proteins in the pull-down assay. The bait proteins, GST-Msx1 and GST, are indicated at the bottom of the figure. Input hexahistidine-Dlx3, Dlx3 1–252 aa and Dlx3 mutated NLS sequences [1+2] proteins combined with the bait proteins in the pull-down reaction are indicated below each lane as Dlx3, 1–252 and [1+2], respectively. Relative molecular mass is indicated in kDa at the left side of the figure.

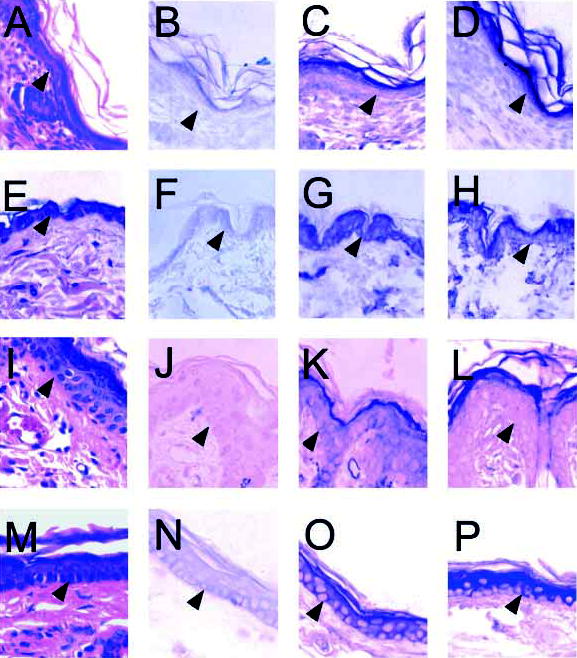

Immunohistochemical analysis of murine stratified epithelium was performed to identify the location of Dlx3 and Msx1 protein expression in vivo in differentiating murine epidermis from various anatomical locations. Hematoxylin and Eosin-stained sections were used to examine epithelial histology (Fig. 3A,E,I,M). Pre-immune rabbit serum was used as a control for antibody specificity. Fig. 3B,F,J,N shows faint background staining by pre-immune serum. Dlx3 was detected in differentiated cells corresponding primarily to the flattened granular cell layer (Fig. 3C,G,K,O). Like Dlx3, Msx1 was detected primarily in the differentiated, flattened granular cell layer (Fig. 3D,H,L,P). Clearly, the expression levels of Dlx3 and Msx1 varied between the different epithelial sites; however, both proteins were always detected in the differentiated layers of the stratified epithelium. Thus, Dlx3 and Msx1 proteins are expressed and have putative functions in the same cells of the murine epidermis.

Fig. 3.

Immunohistochemical analysis of murine neonatal stratified epithelium and adult murine stratified epithelial tissue.(A–D) Murine neonatal epithelium. (E–H) Adult murine trunk epithelial tissue. (I–L) Adult murine whisker pad epithelium. (M–P) Adult murine ear epithelial tissue. (A,E,I,M) Sections were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin. (B,F,J,N) Immunohistochemical analysis of sections using pre-immune rabbit serum as a negative control for non-specific antibody binding. (C,G,K,O) Immunohistochemical analysis to detect Dlx3 protein. (D,H,L,P) Immunohistochemical analysis to detect Msx1 protein. The basal cell layer is indicated by arrowheads. Original magnification 400×.

Dlx3 intracellular localization

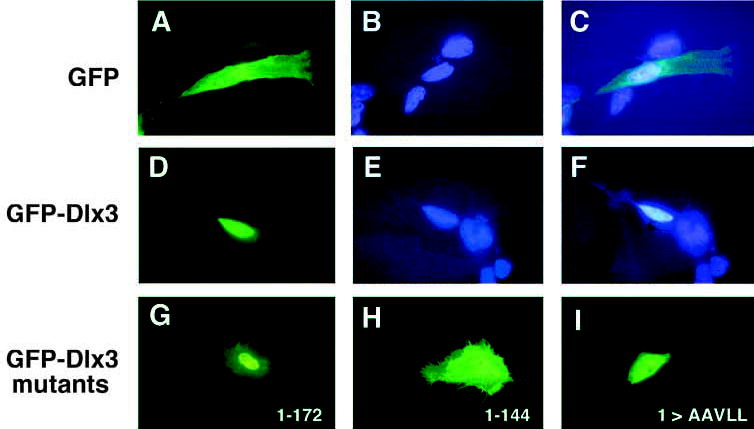

Primary mouse keratinocytes were grown on glass coverslips in EMEM with 8% chelated FBS. Cells were transiently transfected with pEGFP-C1 or pEGFP-Dlx3 plasmid DNA and Ca2+ levels maintained at 0.05 mM or increased to 0.12 or 1.4 mM to induce differentiation in vitro. Intracellular localization of GFP proteins was observed by direct fluorescence microscopy. The location of the nucleus was apparent by DAPI staining. GFP was detected as bright green fluorescence throughout the cell (Fig. 4A–C). GFP-Dlx3 was detected, regardless of the calcium-induced keratinocyte differentiation state, as highly concentrated fluorescence in the nucleus (Fig. 4D–F shows a cell grown in 1.4 mM Ca2+).

Fig. 4.

Transient expression of GFP fusion proteins in primary murine keratinocytes induced to differentiate by Ca2+. GFP, GFP-Dlx3 and GFP-Dlx3 mutant fusion proteins were expressed in primary murine keratinocytes growth in 1.4 mM Ca2+ and visualized by direct fluorescence microscopy. (A–C) The same image of a GFP-expressing cell, using (A) an FITC filter, (B) a DAPI filter; (C) a double image of FITC plus DAPI. (D,E) The same image of a GFP-Dlx3 expressing cell, using an FITC filter (D) or a DAPI filter (E); (F) a double image of FITC plus DAPI. The DAPI counterstain indicates the location of the nucleus within the cell. (G–I) Images generated using the FITC filter. (G) A cell expressing GFP-Dlx3 1-172 aa. (H) A cell expressing GFP-Dlx3 1–144 aa. (I) A cell expressing GFP-Dlx3 with the first basic region of the NLS bipartite sequence mutated to alanine and leucine residues ([1]> AAVLL). Original magnification 800×.

Dlx3 bipartite NLS

Deletions, both 5′ and 3′, were performed on Dlx3 sequences to delineate the region of Dlx3 harboring the NLS. The deletions were cloned in-frame into pEGFP-C1 and expressed as GFP fusion proteins by transient transfection of primary mouse keratinocytes. The intracellular localization of three GFP-Dlx3 mutant proteins, 1–172 aa, 1–144 aa, and NLS sequence [1] mutated basic amino acids [1]>AAVLL, are depicted in Fig. 4G,H,I, respectively.

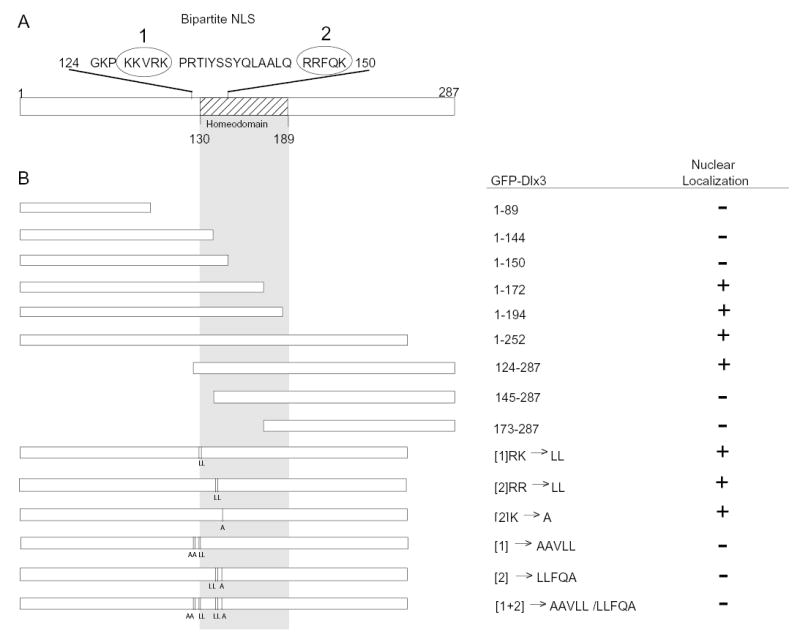

The NLS was determined to reside between aa 127 and 172 (Fig. 5). Both GFP-Dlx3 1-172 aa and GFP-Dlx3 124–287 aa localized primarily to the nucleus whereas GFP-Dlx3 1–144 aa and GFP-Dlx3 145–287 aa were found to be expressed throughout the cells. As indicated in bold in Fig. 5A, the sequence between aa 124 and 150 contains a number of basic residues that fall into a characteristic bipartite NLS pattern (Dingwall and Laskey, 1991). The first basic cluster of the bipartite NLS sequence, [1], is separated from the second basic cluster of the NLS bipartite sequence, [2], by 14 aa. Specific basic residues were substituted (Fig. 5B) with neutral alanine or leucine residues and their intracellular localization examined by fluorescence microscopy. Leucine substitutions of aa 130 and 131 ([1] RRK>LL), 146 and 147 ([2] RR>LL), or an alanine substitution of just aa 150 ([2] K>A) alone, did not affect nuclear localization. However, substituting all the basic residues in sequence [1] or sequence [2] of the proposed bipartite NLS resulted in the loss of nuclear localization. Sequence [1] residues were required but not sufficient for nuclear localization, as substituting just these residues resulted in a loss of nuclear localization. Furthermore, having these sequences, in the truncated Dlx3 1–144 aa, was not sufficient for nuclear localization. Likewise, sequence [2] residues are required but not sufficient for nuclear localization. The sequence [2] basic residue substitution mutant and the truncated Dlx3 145–287 aa, which contained only sequence [2] of the bipartite NLS, did not localize to the nucleus (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Schematic representation of mutated Dlx3 proteins that were fused to GFP and expressed by transient transfection in primary murine keratinocytes. (A) A schematic representation of full-length Dlx3, 1–287 aa, with the homeodomain sequences depicted by cross-hatched box (130–189aa). The putative bipartite NLS sequence (124–150 aa) is spelled out with the bipartite sequence [1] and sequence [2] enclosed in circles. The amino acids that were substituted with neutral alanine or leucine residues are indicated in bold. (B) The left side of the figure graphically illustrates the 3′ and 5′ Dlx3 truncation mutations, which were cloned and expressed as GFP-mutant Dlx3 fusion proteins. The gray shaded area indicates the location of the homeodomain. The vertical lines and L and A letters indicate the location and substitution residues for the NLS bipartite basic residues of sequence [1] or sequence [2]. The right side of the figure lists the aa of Dlx3 present in each GFP-mutated Dlx3 protein and indicates the location of intracellular expression as determined by direct fluorescence microscopy. +, nuclear fluorescence localization; −, a fluorescence pattern throughout the cell, similar to GFP alone (see Fig. 4). The substitution mutations are designated by the NLS bipartite sequences [1], [2] or [1+2]. The basic residue(s) within that sequence that were substituted are indicated followed by the neutral residues to which the sequences were mutated (i.e. [1]RK>LL). All the basic residues have been substituted in those cases in which the basic residues of sequence [1] or [2] are not listed (i.e. [1]>AAVLL).

To confirm that the proposed bipartite basic clusters, sequences [1+2], together constitute a complete NLS, and that this is sufficient for nuclear localization, sequences encoding Dlx3 124–150 aa were subcloned into a construct encoding a cytoplasmic fusion protein. The pEGFP-C1-K14 construct (a kind gift from the laboratory of Dr Robert Goldman, Northwestern University), encodes a GFP-K14 fusion protein of approximately 85 kDa. Molecules less than approximately 30 kDa can passively diffuse through the NPC (Imamoto et al., 1998; Izaurralde and Adam, 1998). K14 forms filamentous keratin bundles that radiate through the cytoplasm (Fig. 6A). The putative Dlx3 bipartite NLS sequence was cloned in-frame between the GFP and K14 genes and expressed by transient transfection of primary mouse keratinocytes. Although minor filamentous cytoplasmic expression was detected on occasion, predominant GFP-NLS-K14 expression was detected in the nucleus of transfected cells (Fig. 6B).

Dlx3 NLS sequences and Dlx3 function

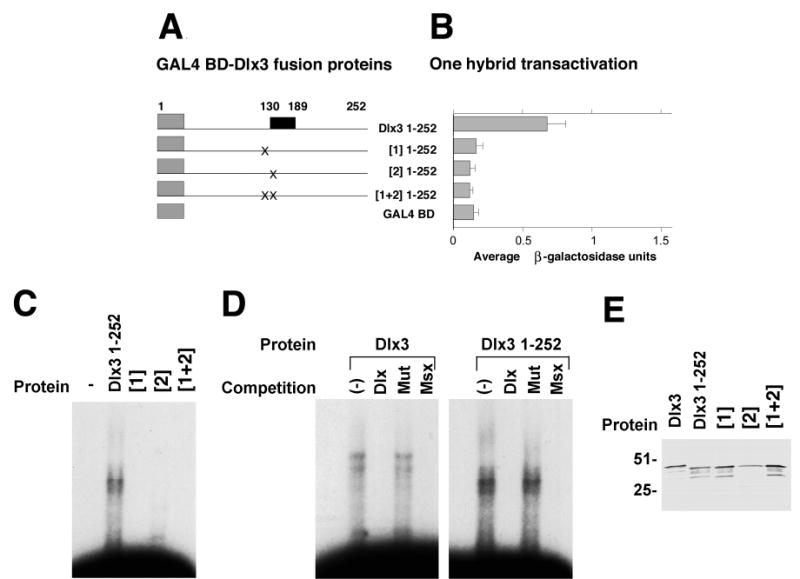

The Dlx3 bipartite NLS is located N-terminal to and includes the N-terminal portion of the homeodomain (Fig. 5A). Therefore we postulated that sequences within the NLS may be required to maintain the transactivation and binding capacities of the Dlx3 protein. Dlx3 bipartite NLS substitution mutants of region [1], [2] and/or [1+2] were assayed for their ability to transactivate, bind DNA and interact with Msx1. For ease of cloning, the proteins were expressed as C-terminal truncation proteins containing aa 1–252. This deletion construct (Dlx3 1–252) included the putative transactivation domains, the homeodomain, and sequences necessary for DNA or Msx1 binding. The Dlx3 1–252 protein maintained all the Dlx3 function capacities (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Dlx3 NLS sequences and Dlx3 protein function. (A,B) Transactivation potential of Dlx3 1–252 and Dlx3 1–252 NLS mutated proteins determined by a yeast one-hybrid assay. (A) The GAL4 BD-Dlx3 1–252 and GAL4 BD-Dlx3 1–252 NLS mutated fusion proteins. The gray boxes represent the GAL4 BD, the black box indicates the homeodomain region and the lines represent the Dlx3 or mutated Dlx3 sequences that correspond to the amino acid numbers indicate on the left side of B. (B) The averaged results of three one-hybrid experiments. Each culture was tested in duplicate in the liquid culture β-galactosidase assay. The pattern of transactivation of Dlx3 NLS mutant proteins compared to wild-type Dlx3 was reproducible. β-galactosidase units are an indirect measure of transactivation potential, and were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Mean β-galactosidase units ± s.d. are recorded on the x-axis. GAL4 BD-Dlx3 fusion proteins are recorded on the y-axis. GAL4 BD alone is included to indicate the level of background transactivation in the assay. (C) Gel mobility-shift assays to assess Dlx3 1–252 aa protein and Dlx3 1–252 NLS mutant protein binding to Dlx3 consensus binding site ds oligonucleotide probe DNA. The first lane contains free probe. Lanes 2–5 show gel mobility shifts produced by proteins Dlx3 1–252 aa (Dlx 1–252), Dlx3 1–252 with mutated basic residues in the first NLS bipartite sequence [1], Dlx3 1–252 with mutated basic residues in the second NLS bipartite sequence [2] and Dlx3 1–252 with mutated basic residues in the both NLS bipartite sequences [1+2]. (D) Gel mobility-shift assays to assess Dlx3 and Dlx3 1–252 aa protein binding to Dlx3 consensus binding site ds oligonucleotide probe DNA. The first lane of each photomicrograph contains free probe, followed by a non-competed lane (−). Lanes 3, 4 and 5 contain competition mobility-shift assays with 100-fold excess cold competitor Dlx3 consensus binding site (Dlx), mutated Dlx3 binding site (Mut), and Msx1 consensus binding site (Msx) ds oligonucleotides, respectively. (E) Anti-T7 immunoblot of recombinant hexahistidine-Dlx3 1–252 and Dlx3 1–252 NLS mutant proteins that contain the T7-epitope tag. Lane 1, full-length Dlx3 protein; lane 2, Dlx3 1–252 protein, (Dlx3 1–252); lane 3, Dlx3 1–252 with mutated basic residues in the first NLS bipartite sequence [1]; lane 4, Dlx3 1–252 with mutated basic residues in the second NLS bipartite sequence [2]; lane 5, Dlx3 1–252 with mutated basic residues in the both NLS bipartite sequences [1+2]. Relative molecular mass is indicated in kDa at the left side of E.

The one-hybrid transactivation assay revealed that substitution of the basic residues in the NLS [1] sequence, which lies within the N-terminal arm of the homeodomain and extends N-terminal to it, or the NLS [2] sequence, which resides within the homeodomain, had the same deleterious effect. Transactivation potential was reduced to background levels (Fig. 7A,B), even though the regions required for transactivation defined in Fig. 1 had not altered.

The NLS substitution mutants were expressed as hexahistidine fusion proteins and assayed for their ability to specifically bind DNA at the Dlx3 consensus-binding site. The gel mobility-shift in Fig. 7C, clearly shows Dlx3 1–252 aa protein binding; however, the NLS substitution mutants of region [1], [2] and [1+2] all failed to bind the DNA. These mutations did not alter the sequence of the homeodomain third helix that has been described as the region involved in direct, major groove DNA binding. However, they do overlap the homeodomain N-terminal arm that has been associated with minor groove DNA recognition and binding. Competition mobility-shift assays using a 100-fold excess of unlabeled Dlx3 consensus-binding site, mutated binding site or Msx1 consensus-binding site ds oligonucleotides, demonstrated that Dlx3 1–252 protein efficiently bound the Dlx3 probe DNA (Fig. 7D). The gel-shift complex was competed with the Dlx3 and the Msx1 consensus-binding site oligonucleotides, but not the mutated Dlx3 binding site oligonucleotide (Fig. 7D). These data indicate, as previously shown by Feledy et al. (1999) for the Xenopus Dlx3, the necessity of the TAATT sequence for specific Dlx3 DNA binding.

In addition to assaying for DNA binding, the NLS substitution mutant of regions [1+2] was tested in the Msx1 pull-down assay. Immunoblot confirmed protein expression. GST-Msx1 was unable to bind and pull-down the Dlx3 NLS [1+2] substitution mutant protein (Fig. 2, lanes 3,6).

DISCUSSION

The process of cellular differentiation is a result of differential gene expression regulated through the specific function of transcription factors, and the function is dependent on nuclear localization, DNA binding and transactivating properties. Transcription factors themselves are subject to regulation at many levels. It has been proposed that Dlx3 is involved in regulating expression of differentiation specific genes in the interfollicular epidermis (Morasso et al., 1996). In this study we examined the functional capacities of the murine Dlx3 protein. Our in vitro studies demonstrate that Dlx3 is a transcriptional activator that can specifically bind the TAATT DNA motif. The specific genes regulated by Dlx3 transactivation in vivo have yet to be identified. Based on studies examining Msx1 and Dlx3 transcript expression (Bendall and Abate-Shen, 2000; Davidson, 1995; Robinson and Mahon, 1994; Sargent and Morasso, 1999), we postulate that Msx1 and Dlx3 proteins may interact with one another. We present in vitro evidence that the murine Msx1 and Dlx3 proteins are capable of binding to one another, presumably to form a heterodimer complex. In addition, the immunohistochemical Dlx3 and Msx1 protein expression data support the potential for Dlx3 and Msx1 proteins to interact with one another in vivo. Both Dlx3 and Msx1 are clearly expressed in murine epidermal tissues in approximately the same differentiated cell layers, although variability in the expression levels between the two proteins at specific epithelial tissue sites was noted.

Transcription factors such as NFκB are functionally restricted by intracellular compartmentalization (Seitz et al., 1998). Specific events occur within the cell to allow NFκB to migrate to the nucleus and transactivate genes. As Dlx3 is believed to be a differentiation-specific transactivator; it could be postulated that its function is regulated by compartmentalization due to differentiation-specific factors. Our data, however, indicate that Dlx3 is detected only in the nucleus and is expressed only in terminally differentiated cells in vivo. Therefore, regulation at the levels of transcription or translation appear to be more probable than intracellular compartmentalization.

Our understanding of nuclear transport has increased dramatically in recent years (Imamoto et al., 1998; Izaurralde and Adam, 1998; Jans and Hassan, 1998). The NPC is composed of a large number of molecules, which create highly regulated channels that mediate transport through the nuclear membrane. For active transport into the nucleus, a given protein must contain an NLS that is recognized by an importin transport receptor, which facilitates NPC recognition and translocation into the nucleus. Although homeodomain proteins must be transported into the nucleus to function as transcriptional regulators, only a few NLS have been described (Carriere et al., 1995; Ghaffari et al., 1997; Kasahara and Izumo, 1999; Meisel and Lam, 1996; Sock et al., 1996).

Once in the nucleus, Dlx3 can function as a transcriptional activator. In this study, we have clearly delineated a Dlx3 bipartite NLS sequence. The Dlx3 NLS redirection of expression of K14 to the nucleus shown with GFP-Dlx3 NLS-K14, clearly indicates that the Dlx3 NLS is sufficient for nuclear localization. By mutational analysis we have shown that some residues in the NLS are necessary for nuclear localization in vitro. However, since the Dlx3 NLS lies proximal to and within the homeodomain, which is required for DNA binding, it cannot be conclusively demonstrated using the mutation set we have presented that the bipartite NLS is the in vivo mechanism of nuclear localization.

It is interesting to note that two other reports of homeodomain proteins have described single NLS sequences that are necessary but not sufficient for translocation to the nucleus. The identified TTF-1/Nkx2.1 and Nkx2.5 NLS sequences (Ghaffari et al., 1997; Kasahara and Izumo, 1999) correspond to sequence [1] of the Dlx3 bipartite NLS. Both TTF-1/Nkx2.1 and Nkx2.5 NLS contain basic residues corresponding to Dlx3 NLS sequence [2] in the homeodomain. Based on the apparent homology and basic cluster position within Dlx3, TTF-1/Nkx2.1 and Nkx2.5, it can be proposed that TTF-1/Nkx2.1 and Nkx2.5 may contain bipartite NLS sequences. Alignment of all Dlx and Msx family members suggests putative bipartite NLS within all family members. In addition, the conservation of the NLS position within the homeodomain proteins suggests that the location of the NLS basic residues in relationship to the other functional domains of the protein is significant. However, from the data presented in the Nkx homeoprotein studies (Kasahara and Izumo, 1999), the ‘sufficient’ characteristic of the NLS sequences could not be determined since it was not tested using a heterologous system such as the relocation of GFP-K14 done in this sudy.

Further characterization of the Dlx3 bipartite NLS sequences revealed a link with Dlx3 protein function. Our data confirm that Dlx3 transactivation requires two regions of the protein, one in the N terminus (which includes aa 1–43) and the other just C-terminal to the homeodomain (189–220 aa). This arrangement of two transactivation domains separated by the homeodomain has been described for other homeodomain-containing proteins (Feledy et al., 1999; Ghaffari et al., 1997). Interestingly, in the Xenopus XDlx3 (previously reported as Xdll2) a deletion of the first 43 aa did not significantly alter the transcriptional potential (Feledy et al., 1999). In the overall background of the two proteins, Dlx3 and XDlx3, the first transactivation domain placement appears to be located near the N terminus; however, the exact residues comprising the domain have not been defined. The complete Dlx3 N-terminal region (1–127 aa) has remarkable transactivation potential, which is significantly reduced when the homeodomain is included (1–189 aa). This observation suggests a transcriptional regulatory role, possibly dictated by protein conformation, for the homeodomain.

A human disorder, TDO syndrome, has been associated with a 4-nucleotide deletion in the human DLX3 gene (Price et al., 1998). The deletion is positioned just C-terminal to the homeodomain, resulting in a frameshift and premature termination of the protein. The DLX3 TDO protein does not contain the second transactivation domain, the removal of which we have shown severely compromises the transactivation potential of the murine Dlx3 protein. Therefore, although DLX3 TDO does localize to the nucleus (our unpublished data), with the given combination of having only a single transactivation domain and aberrant C-terminal sequences resulting from the frameshift, altered DLX3 TDO transactivation potential would be expected.

We have shown that mutating the murine Dlx3 bipartite NLS basic residues result in a reduction in transactivation potential. The Dlx3 bipartite NLS does not reside within either transactivation domain. Thus mutating the Dlx3 NLS did not directly alter either transactivation domain, suggesting that the Dlx3 NLS basic residues play an indirect role in transactivation, possibly by influencing the three-dimensional structure of the protein.

In a similar manner, we have shown that the Dlx3 NLS basic residues are necessary for specific Dlx3:DNA binding. Homeodomain protein direct DNA binding has been shown to occur through the third helix of the homeodomain (Catron et al., 1995; Gehring et al., 1994b). This helical structure forms direct DNA contact through the major groove (Billeter et al., 1993; Kissinger et al., 1990). In addition, it has been proposed that the N-terminal arm of the homeodomain is oriented such that it inserts into the minor groove of the DNA and may contribute significantly to DNA binding specificity (Billeter et al., 1993; Gehring et al., 1994b; Kissinger et al., 1990; Lin and McGinnis, 1992; Scott et al., 1989; Shang et al., 1994). The Dlx3 bipartite NLS sequence [1] lies within the N-terminal arm and extends N-terminal to it. We have demonstrated that mutating these sequences resulted in a loss of DNA binding. Therefore, it can be proposed that mutating the Dlx3 bipartite NLS sequence [1] may directly interfere with minor groove DNA recognition and binding. Interestingly, mutating the Dlx3 NLS sequence [2] also resulted in a loss of DNA binding. This sequence lies within the final turn of the first helix of the homeodomain, spatially very distant from the DNA. Thus, the NLS basic residues are necessary for Dlx3:DNA binding most probably by both forming direct contact with the minor groove of DNA and indirectly by affecting the structure of the homeodomain.

Lastly, we have shown that Dlx3 can bind the homeodomain protein Msx1. Zhang et al. (1997) have proposed that Dlx and Msx proteins are functional antagonists that compete for DNA binding and abrogate each other’s function through heterodimerization. Heterodimerization was shown to be mediated through homeodomain residues corresponding to DNA binding. Therefore, if this is true of Dlx3 and Msx1, it is not unexpected that a Dlx3 mutation, which abolishes DNA binding, would also abolish Msx1 protein binding. Our Dlx3 mutated NLS GST-Msx1 pull-down data clearly supports this hypothesis.

The murine Dlx3 protein is a transcription factor that requires nuclear localization to exert its function. In this study we have shown that Dlx3 nuclear localization can be directed by a bipartite NLS located at the N terminus of the homeodomain. Dlx3 transactivation, DNA binding and Dlx3:Msx1 protein interaction all require the Dlx3 bipartite NLS basic residues. The data presented here strongly suggest that the NLS basic residues affect the functional integrity of the Dlx3 protein, possibly influencing the functional structure of the Dlx3 protein.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Peter Steinert for his encouragement and support, Ulrike Lichti for providing cell culture resources and Ca2+ concentration determinations, Will Idler for help in protein purification, George Poy for sequence analysis and Geon Tae Park for critical reading of the manuscript.

References

- Anderson S, Eisenstat D, Shi L, Rubenstein J. Interneuron migration from basal forebrain to neocortex: Dependence on Dlx gene. Science. 1997;278:474–476. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5337.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendall AJ, Abate-Shen C. Roles for Msx and Dlx homeoproteins in vertebrate development. Gene. 2000;247:17–31. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billeter M, Qian Y, Otting G, Muller M, Gehring W, Wuthrich K. Determination of the nuclear magnetic resonance solution structure of an Antennapedia homeodomain-DNA complex. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:1084–1097. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carriere C, Plaza S, Caboche J, Dozier C, Bailly M, Martin P, Saule S. Nuclear localization signals, DNA binding, and transactivation properties of Quail Pax-6 (Pax-QNR) Isoforms. Cell Growth Diff. 1995;6:1531–1540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catron K, Iler N, Abate C. Nucleotides flanking a conserved TAAT core dictate the DNA binding specificity of 3 murine homeodomain proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2354–2356. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.4.2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catron K, Zhang H, Marshall S, Inostroza J, Wilson J, Abate C. Transcriptional repression by Msx-1 does not require homeodomain DNA-binding sites. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:861–871. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.2.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson D. The function and evolution of Msx genes: Pointers and paradoxes. Trends Genet. 1995;11:405–411. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)89124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingwall C, Laskey R. Nuclear targeting sequences – a consensus? Trends Biochem Sci. 1991;16:478–481. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90184-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert R, Welter J. Transcription factor regulation of epidermal keratinocyte gene expression. Mol Biol Rep. 1996;23:59–70. doi: 10.1007/BF00357073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feledy J, Morasso M, Jang S, Sargent T. Transcriptional activation by the homeodomain protein Distal-less 3. Nucleic Acid Res. 1999;27:764–770. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.3.764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs E, Byrne C. The epidermis: Rising to the surface. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1994;4:725–736. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(94)90140-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring W, Affolter M, Burglin T. Homeodomain proteins. Ann Rev Biochem. 1994a;63:487–526. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.002415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring W, Qian Y, Billeter M, Furukubo-Tokunaga K, Schier A, Resendez-Perez D, Affolter M, Otting G, Wuthrich K. Homeodomain-DNA recognition. Cell. 1994b;78:211–223. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90292-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaffari M, Zeng X, Whitsett J, Yan C. Nuclear localization domain of thyroid transcription factor-1 in respiratory epithelial cells. Biochem J. 1997;328:755–761. doi: 10.1042/bj3280757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennings H, Michael D, Cheng C, Steinert P, Holbrook K, Yuspa S. Calcium regulation of growth and differentiation of mouse epidermal cells in culture. Cell. 1980;19:245–254. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill R, Jones P, Rees A, Sime C, Justice M, Copeland N, Jenkins N, Graham E, Davidson D. A new family of mouse homeo box-containing genes: Molecular structure, chromosomal location and developmental expression of Hox-7.1. Genes Dev. 1989;3:26–37. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamoto N, Kamei Y, Yoneda Y. Nuclear transport factors: Function, behavior and interaction. Eur J Histochem. 1998;42:9–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izaurralde E, Adam S. Transport of macromolecules between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. RNA. 1998;4:351–364. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jans D, Hassan G. Nuclear targeting by growth factors, cytokines, and their receptors: A role in signaling? BioEssays. 1998;20:400–411. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199805)20:5<400::AID-BIES7>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara H, Izumo S. Identification of the in vivo casein kinase II phosphorylation site within the homeodomain of the cardiac tissue-specifying homeobox gene product Csx/Nkx2.5. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:526–536. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissinger C, Liu B, Martin-Blanco E, Kornberg T, Pabo C. Crystal structure of an engrailed homeodomain-DNA complex at 2.8 A resolution: A framework for understanding homeodomain-DNA interactions. Cell. 1990;63:579–590. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90453-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughon A. DNA binding specificity of homeodomains. Biochemistry. 1991;30:11358–11367. doi: 10.1021/bi00112a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichti U, Yuspa S. Modulation of tissue and epidermal transglutaminases in mouse epidermal cells after treatment with 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate and/or retinoic acid in vivo and in culture. Cancer Res. 1988;48:74–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L, McGinnis W. Mapping functional specificity in the Dfd and Ubx homeo-domains. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1071–1081. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.6.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisel L, Lam E. The conserved ELK-homeodomain of KNOTTED-1 contains two regions that signal nuclear localization. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;30:1–14. doi: 10.1007/BF00017799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morasso M, Grinberg A, Robinson G, Sargent T, Mahon K. Placental failure in mice lacking the homeobox gene Dlx3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:162–167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morasso M, Mahon K, Sargent T. A Xenopus distal-less gene in transgenic mice: Conserved regulation in distal limb epidermis and other sites of epithelial-mesenchymal interaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3968–3972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morasso M, Markova N, Sargent T. Regulation of epidermal differentiation by Distal-less homeodomain gene. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1879–1887. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.6.1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price J, Bowden D, Wright J, Pettenati M, Hart T. Identification of a mutation in Dlx3 associated with tricho-dento-osseous (TDO) syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:563–569. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.3.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu M, Bulfone A, Ghattas I, Meneses J, Christensen L, Sharpe P, Presley R, Pederson R, Rubenstein J. Role of the Dlx homeobox genes in proximodistal patterning of the brachial arches: Mutations of Dlx-1, Dlx-2, and Dlx-1 and -2 alter morphogenesis of proximal skeletal and soft tissue structures derived from the first and second arches. Dev Biol. 1997;185:165–184. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson G, Mahon K. Differential and overlapping domains of Dlx-2 and Dlx-3 suggest distinct roles for Distal-less homeobox genes in craniofacial development. Mech Dev. 1994;48:199–215. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(94)90060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent, T. and Morasso, M. (1999). Differentiation of Vertebrate Epidermis. In Cell Lineage and Fate Determination (ed. S. A. Moody), pp. 553–567. New York: Academic Press.

- Scott M, Tamkun J, Hartzell G. The structure and function of the homeodomain. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;989:25–48. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(89)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitz C, Lin Q, Deng H, Khavari P. Alterations in NFkB function in transgenic epithelial tissue demonstrate a growth inhibitory role for NFkB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2307–2312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Z, Isaac V, Li H, Patel L, Catron K, Curran T, Montelione G, Abate C. Design of a ‘minimAl’ homeodomain: The N-terminal arm modulates DNA binding affinity and stabilizes homeodomain structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8373–8377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sock E, Enderich J, Rosenfeld M, Wegner M. Identification of the nuclear localization signal of the POU domain protein Tst-1/Oct6. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17512–17518. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuspa S, Kilkenny A, Steinert P, Roop D. Expression of murine epidermal differentiation markers is tightly regulated by restricted extracellular calcium concentrations in vitro. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:1207–1217. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.3.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Catron K, Abate-Shen C. A role for the Msx-1 homeodomain in transcriptional regulation: Residues in the N-terminal arm mediate TATA binding protein interaction and transcriptional repression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1764–1769. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Hu G, Wang H, Sciavolino P, Iler N, Shen M, Abate-Shen C. Heterodimerization of Msx and Dlx homeoproteins results in functional antagonism. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2920–2932. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]