Abstract

Cucurbit yellow vine disease (CYVD) is caused by disease-associated Serratia marcescens strains that have phenotypes significantly different from those of nonphytopathogenic strains. To identify the genetic differences responsible for pathogenicity-related phenotypes, we used a suppressive subtractive hybridization (SSH) strategy. S. marcescens strain Z01-A, isolated from CYVD-affected zucchini, was used as the tester, whereas rice endophytic S. marcescens strain R02-A (IRBG 502) was used as the driver. SSH revealed 48 sequences, ranging from 200 to 700 bp, that were present in Z01-A but absent in R02-A. Sequence analysis showed that a large proportion of these sequences resembled genes involved in synthesis of surface structures. By construction of a fosmid library, followed by colony hybridization, selection, and DNA sequencing, a phage gene cluster and a genome island containing a fimbrial-gene cluster were identified. Arrayed dot hybridization showed that the conservation of subtracted sequences among CYVD pathogenic and nonpathogenic S. marcescens strains varied. Thirty-four sequences were present only in pathogenic strains. Primers were designed based on one Z01-A-specific sequence, A79, and used in a multiplex PCR to discriminate between S. marcescens strains causing CYVD and those from other ecological niches.

Cucurbit yellow vine disease (CYVD) was first observed in squash (Cucurbita maxima) and pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo) in 1988 in Oklahoma and Texas (6). Since then, the disease has been confirmed in nine other states (5, 34). CYVD is characterized by rapid and general yellowing of leaves appearing over a 3- to 4-day period, followed by gradual or rapid decline and death of the vine in several cucurbit crops (6).

DNA-DNA hybridization (36) and groE and 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis (7) identified the causal agent of CYVD as a nonpigmented strain of the cosmopolitan bacterium Serratia marcescens (24). Non-CYVD strains of this species can assume roles as soil- or water-resident saprophytes, plant endophytes, insect pathogens, and even opportunistic human pathogens. None of the other strains tested is able to cause CYVD (B. D. Bruton, personal communication), and phenotypic differences between them and CYVD pathogenic strains include substrate utilization and fatty acid profiles (24). Repetitive extragenic palindromic PCR-based fingerprinting and DNA-DNA hybridization also revealed significant differentiation between CYVD pathogenic strains of S. marcescens and strains from other niches (36). Much remains to be learned, however, about the genes that are responsible for the differences.

Suppressive subtractive hybridization (SSH) is a powerful method for identifying DNA fragments that are present in one organism (tester) but absent from another (driver), especially if the two organisms are closely related (1). It has been widely used for bacterial genome analysis to discover new epidemiological markers, virulence factors, or host specificity determinants (35). In this work, our goal was to identify the genetic differences responsible for S. marcescens pathogenicity in cucurbits. We compared the genomes of a CYVD strain, Z01-A, and a rice endophytic strain, R02-A, in an effort to identify genes or genetic markers present in the phytopathogenic strain but absent from a closely related nonpathogenic strain. We report the identification of a pool of DNA sequences specific to CYVD pathogenic strains. In addition, we identified a cluster of genes that appeared to have bacteriophage origins and a genome island containing genes putatively responsible for type 1 fimbrial (pilus) synthesis. Knowledge of sequences present only in CYVD strains allowed the design of a primer set specific for CYVD for use in diagnosis of the disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

Test bacteria included several S. marcescens strains from different ecological niches and several CYVD strains from different cucurbit hosts (Table 1). Bacteria were stored at −80°C in aliquots of 1.5 ml Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (30) containing 15% glycerol. For use in experiments, bacteria were streaked onto LB agar and incubated at 28°C for 24 h. Escherichia coli was grown at 37°C on LB agar or in LB broth.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains tested in this study and their relative relatedness to CYVD representative strain C01-A

| Strain designation used in this study | Alternative strain designation | Source | RBR to C01-Ae |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYVD pathogenic strains | |||

| W01-A | Watermelon | 100 | |

| W09-A | Watermelon | 100 | |

| Z01-A | Zucchini | 100 | |

| P01-A | Pumpkin | 94 | |

| P07-A | 00B058 | Pumpkin | ND |

| C01-A | Cantaloupe | 100 | |

| CYVD nonpathogenic strains | |||

| R01-Aa | IRBG 501 | Rice | 82 |

| R02-Aa | IRBG 502 | Rice | 90 |

| R03-Aa | IRBG 505 | Rice | ND |

| G01b | 90-166 | Cotton | 76 |

| H01-Ac | Human | 73 | |

| H02-Ac | Human | 82 | |

| Db11d | Insect | ND |

Provided by J. K. Ladha, International Rice Reasearch Institute, Los Banos, Philippines.

Provided by J. Kloepper, University of Alabama, Auburn.

Provided by D. Adamson, Medical Arts Laboratory, Oklahoma City, OK.

Provided by M. W. Tan, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA.

RBR, relative binding ratio; ND, not done. Results were reported by Zhang et al. (36).

DNA manipulation.

Genomic DNAs of CYVD-causing and nonphytopathogenic S. marcescens strains were isolated by using a bacterial genomic DNA miniprep protocol (2). Plasmid DNA of subtracted library colonies was isolated by the alkaline lysis miniprep protocol (30).

Suppressive subtractive hybridization and differential screening.

CYVD strain Z01-A was subtracted from a rice endophytic S. marcescens strain, R02-A, using a Clontech PCR-select Bacterial Genome Subtraction Kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). The hybridization temperature was set at 68°C to accommodate the high G+C content of S. marcescens. The numbers of cycles for primary and secondary PCR were 26 and 12, respectively. Subtracted sequences were inserted into the TA vector using the TOPO TA Cloning kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and electroporated into One Shot TOP10 Electrocomp E. coli according to the manufacturer's protocol. Subtracted library clones were randomly selected as templates for PCR amplification using nested primers 1 and 2R, provided in the genome subtraction kit. To confirm that the insert sequences in these clones are truly specific to S. marcescens Z01-A, the PCR products were transferred to duplicate nylon membranes using a dot blot method (19). Each membrane was probed (2) with genomic DNA of a CYVD or a nonphytopathogenic strain. The digoxigenin-labeled probe was detected with disodium 3-(4-meth-oxyspiro {1,2-dioxetane-3,2′-(5′-chloro) tricyclo [3.3.1.13,7] decan}-4-yl) phenyl phosphate (Roche, Switzerland), and exposures were from 30 min to 3 h.

DNA sequencing and analysis.

Insert sequences in the subtracted library were sequenced by the Oklahoma State University Recombinant DNA/Protein Resource Facility. Sequencing reactions were performed as recommended by the supplier (Applied Biosystems, Inc.) and analyzed by using an ABI 3100 automated DNA sequencer. Probable biological functions of the products encoded by genes in the raw sequences were identified using MyPipeOnline 2.00b, a program designed by the Oklahoma State University bioinformatics group (3). Based on the analysis, redundant sequences were identified and contigs were formed. Individual sequences were also analyzed by BLASTX and/or BLASTN searches against the GenBank database.

Fosmid cloning and hybridization.

A Z01-A fosmid library was constructed using a CopyControl Fosmid Library Production Kit (Epicenter, Madison, WI). Library construction was performed using recommended protocols, with slight modifications. Briefly, gel slices containing fractionated DNA were washed twice with 1× GELase Digestion Buffer before being incubated with GELase for digestion. To induce fosmid clones to high copy numbers, the induction solution was added just before the bacterial culture reached log phase. The incubation period was held to 3 hours or less to avoid toxicity.

E. coli colonies containing fosmid clones were transferred and fixed to Hybond N+ nylon membranes (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) following the manufacturer's instructions. Equal amounts of PCR amplicons of subtracted Z01-A unique sequences, amplified using nested primers 1 and 2R provided in the genome subtraction kit, were pooled and labeled using a DIG DNA Labeling Kit (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany). The probe was then hybridized to the blot as described for colony hybridization.

Once a few fosmid clones were shown to contain phytopathogenic-strain unique sequences, reverse hybridizations were conducted to confirm the actual number of unique sequences located in each fosmid clone. PCR amplicons of subtracted Z01-A unique sequences were arrayed on a nylon membrane (as described above) and hybridized to a digoxigenin probe made from one fosmid clone. Similar arrays were made and hybridized to other individual fosmid clones as well.

Fosmid sequencing and analysis.

The detailed procedures for cloned large insert genomic DNA isolation, random shotgun cloning, fluorescence-based DNA sequencing, and subsequent analysis were as described previously (4, 10, 22, 26). Briefly, fosmid DNA was isolated from host genomic DNA via a cleared lysate-acetate precipitation-based protocol (22). Subsequently, purified fosmid DNAs, in 50-μg portions, were randomly sheared and made blunt ended (4, 26, 30). After kinase treatment and gel purification, fragments in the 1- to 3-kb range were ligated into SmaI-digested, bacterial alkaline phosphatase-treated pUC18 (Pharmacia), and E. coli strain XL1BlueMRF′ (Stratagene) was transformed by electroporation. Approximately 1,200 colonies were picked from each transformation as a random library and were grown in Terrific Broth medium (30) supplemented with 100 μg/ml of ampicillin for 14 h at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm. The sequencing templates were isolated by a cleared lysate-based protocol (4).

Sequencing reactions were performed as previously described (10, 26) using either the Applied Biosystems Big Dye 3.0 or Amersham ET terminator sequencing reaction mixture. The reaction mixtures were incubated for 60 cycles in a Perkin-Elmer Cetus DNA Thermocycler 9600 under the cycle conditions recommended by the manufacturer. Any unincorporated dye terminators were then removed by ethanol precipitation at room temperature, and after the fluorescence-labeled nested fragment sets were dissolved in double-distilled water, they were resolved by electrophoresis on an ABI 3700 Capillary DNA Sequencer. After base calling with the ABI analysis software, the analyzed data were transferred to a Sun Workstation Cluster and assembled using Phred and Phrap (11, 12). Overlapping sequences and contigs were analyzed using Consed (13). Gap closure and proofreading were performed using either custom primer walking or PCR amplification of the region corresponding to the gap in the sequence, followed by direct sequencing using amplification with nested primers or by subcloning into pUC18 and cycle sequencing with the universal pUC primers (26). In some instances, additional synthetic custom primers were necessary to obtain at least threefold coverage for each base.

The working draft and finished bacterial artificial chromosome sequences were analyzed on Sun workstations using Artemis software (28).

Determination of plasmid or chromosome origin of subtracted sequences.

Subtracted clone a43, which is clustered with a putative plasmid partition gene in the FOSU1 fosmid, was selected as a target for quantitative PCR to determine whether the subtracted sequences are located on the chromosome or on a plasmid. A pair of primers, designated a43F (5′-CGCAGAACATCAACATATCTTAGCC-3′) and a43R (5′-TACCGTAGTAGTGCTGCATGAG-3′), were designed based on a43 using Primer3 software (27). Amplification of a segment of 16S rRNA genes, the genetic marker on the chromosome, was carried out as a control. Genomic DNA and plasmid DNA of Z01-A were prepared from 1.5 ml and 150 ml of log-phase bacterial culture, respectively, and suspended in 50 μl sterile distilled water. Each DNA preparation was diluted 50×, 100×, 200×, 400×, and 800×, and 1 μl of each solution was used in each PCR. PCR conditions for amplification of 16S rRNA genes were as follows: 1 initial denaturation cycle at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 26 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min 30 s, and 1 final extension cycle of 72°C for 10 min. The amplification of a43 was carried out under the same conditions except that the annealing temperature was 60°C.

Multiplex PCR development.

Primers were designed based on CYVD pathogenic-strain-specific sequences using Primer3 software (27). Primers YV1 and YV4, which were designed from the 16S rRNA gene region of the S. marcescens genome and shown to be specific to this species (21), were used together with the new primers in a multiplex PCR to obtain both species and strain specificity. Bacteria grown in broth culture were washed once with 0.5 M NaCl and resuspended in distilled water, and 1 μl suspension was used as a template. Multiplex PCR, performed with the GeneAmp PCR System 9600 (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Überlingen, Germany), was carried out in 25-μl volumes including 5 μl of 5× Git buffer, 0.5 mM of deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 0.1 μM of each primer, and 2 U of Taq DNA polymerase. PCR conditions were as follows: 1 initial denaturation cycle at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 34 cycles of 94°C for 40 s, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min 30 s, and 1 final extension cycle of 72°C for 7 min.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Insert sequences in the subtracted library were deposited in GenBank (Table 2). The sequences of fosmid clones FOSU1 and FOSU2 have been deposited in GenBank and given accession numbers AC148074 and AC148075, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Sequence analysis of Z01-A-specific clones

| Group and clone | Accession no. | First BLASTX matchd | Organism | % identity | Expected value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface structures | |||||

| A3 | CW978589 | AmsI, phosphatase | Shigella flexneri | 58 | 9e-12 |

| A28a | CW978590 | FimC, chaperon | Escherichia coli | 68 | 3e-26 |

| A40 | CW978591 | RmlC, epimerase | S. marcescens | ||

| A48b | CW978592 | FimD, usher protein | Escherichia coli | 56 | 3e-19 |

| B1 | CW978593 | SurA, isomerase | Yersinia pestis | 77 | 1e-13 |

| C15c | CW978594 | FimH, adhesin | Escherichia coli | 55 | 3e-43 |

| C19 | CW978595 | A, rhamnosyl transferase | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 64 | 0.004 |

| B, inverted repeat | S. marcescens | 93 | 8e-09 | ||

| C24a | CW978596 | FimC, chaperon | Escherichia coli | 75 | 9e-21 |

| C25a | CW978597 | FimC, chaperon | Escherichia coli | 53 | 1e-37 |

| C34 | CW978598 | Glycosyltransferase | Campylobacter jejuni | 28 | 1e-04 |

| C63c | CW978599 | FimH, adhesin | Escherichia coli | 86 | 3e-10 |

| C89b | CW978600 | FimD, usher protein | Escherichia coli | 70 | 1e-101 |

| C98b | CW978601 | FimD, usher protein | Escherichia coli | 67 | 6e-47 |

| D6 | CW978602 | FimB, recombinase | Escherichia coli | 58 | 4e-56 |

| Phages | |||||

| A6 | CW978603 | Clp protease | Salmonella typhimurium | 55 | 2e-52 |

| C22 | CW978604 | Phage tail protein | Yersinia pestis | 31 | 8e-16 |

| C62 | CW978605 | Bacteriophage integrase | Escherichia coli | 72 | 9e-53 |

| C67 | CW978606 | Tail assembly protein | Escherichia coli | 64 | 2e-78 |

| D1 | CW978607 | Phage terminase large subunit | Escherichia coli | 80 | 7e-87 |

| Other | |||||

| A23 | CW978608 | Chitobiase | S. marcescens | 89 | 1e-33 |

| A27 | CW978609 | Plasmid partitioning protein | Yersinia enterocolitica | 86 | 5e-28 |

| A66 | CW978610 | Retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator | Bos taurus | 32 | 0.29 |

| A68 | CW978611 | Uridylyltransferase | Aeromonas hydrophila | ||

| A89 | CW978612 | Endonuclease | 56 | 3e-18 | |

| B21 | CW978613 | Dam, regulatory protein | Salmonella typhimurium | 59 | 1e-46 |

| C26 | CW978614 | IstA, transposase | Escherichia coli | 78 | 3e-67 |

| C68 | CW978615 | pVS1 resolvase | Corynebacterium glutamicum | 72 | 3e-07 |

| C93 | CW978616 | TaxC nickase | Escherichia coli | 36 | 0.017 |

| D2 | CW978617 | A, TaxC nickase | Escherichia coli | 34 | 7e-18 |

| B, transcriptional regulator | Escherichia coli | 44 | 1e-05 | ||

| D26 | CW978618 | A, putative exported protein | Yersinia pestis | 67 | 8e-28 |

| B, inverted repeat | S. marcescens | 95 | 6e-11 | ||

| Unknown function | |||||

| A13 | CW978619 | ||||

| A43 | CW978622 | ||||

| A46 | CW978623 | ||||

| A57 | CW978624 | ||||

| A64 | CW978625 | ||||

| A71 | CW978626 | ||||

| A76 | CW978627 | ||||

| A79 | CW978628 | ||||

| A99 | CW978629 | ||||

| B6 | CW978630 | ||||

| B17 | CW978631 | ||||

| C14 | CW978632 | ||||

| C69 | CW978634 | ||||

| C71 | CW978635 | ||||

| C99 | CW978636 | ||||

| D20 | CW978637 | ||||

| D21 | CW978638 | ||||

| D37 | CW978639 |

Clones A28, C24, and C25 matched with different parts of FimC. The first letter in the name of each clone represents a particular sequencing batch.

Clones A48, C89, and C98 matched with different parts of FimD.

Clones C15 and C63 matched with different parts of FimH.

If more than one gene was covered by the clone, they are given as follows: A, gene X; B, gene Y.

RESULTS

Suppressive subtractive hybridization of R02-A from Z01-A.

A Z01-A subtracted library of approximately 400 clones was produced by SSH. Clones from which no amplicon or multiple amplicons were amplified using nested primers 1 and 2R were discarded. To avoid repeated sampling of clones containing the same insert sequences, selection of clones for further characterization was based on their sizes. A total of 183 clones were one-end sequenced, among which 94 different insert sequences were identified. Forty-nine percent of the 94 inserts were represented at least twice. PCR products of the clones representing the 94 were then arrayed as described in Materials and Methods on duplicate nylon membranes and hybridized to Z01-A and R02-A genomic DNA probes. As expected, all the sequences showed hybridization signals with strain Z01-A (data not shown). Forty-six sequences had weak hybridization signals when probed with R02-A genomic DNA. The remaining 48 DNA fragments were present in Z01-A but not in R02-A. These 48 sequences were chosen for further sequence analysis.

A large proportion of the tester-specific sequences resembled genes involved in synthesis of surface molecules.

Analysis of the 48 subtracted sequences by BLASTX search showed that 8 resembled hypothetical bacterial genes of unknown function, while 9 other sequences had no significant matches with known sequences (Table 2). Among the clones that had significant similarity to sequences with known functions, a large proportion were judged to be involved in the synthesis of bacterial surface molecules. Clones A40, C19, and C34 resembled, respectively, genes rmlC, wbbL, and wbbA, which encode proteins of the rhamnose synthesis pathway and have been previously identified in the S. marcescens N28 wb O antigen gene cluster (29). The sequence of the clone B1 insert resembled that of a surA isomerase gene, whose product participates in the assembly of outer membrane proteins (17). A defined surA deletion mutant of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium C5 was defective in the ability to adhere to and invade eukaryotic cells (33). Phosphatase AmsI, the predicted product of clone A3, may be involved in the biosynthesis of extracellular polysaccharide (9).

In addition to the clones mentioned above, nine clones contained sequences resembling fimbrial genes and six others had open reading frames (ORFs) resembling those of phage proteins. Although only one gene for a transposase, namely, istA of insertion element IS21 (25), was identified, it was represented in 38 of the 183 sequenced subtracted clones, indicating its high copy number in the genome.

Identification of two gene clusters.

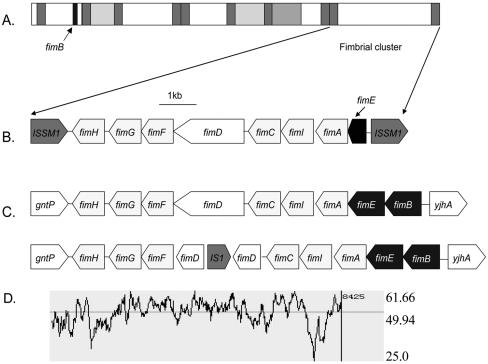

To study the linkage of multiple fimbrial genes, as well as other subtracted sequences, a fosmid library of strain Z01-A containing 410 clones was constructed and maintained on an LB plate. The average size of each clone insert was 40 kb. Using pooled Z01-A-specific sequences as the probe (see Materials and Methods), 19 fosmid clones were positive in colony hybridization. The 10 clones having the strongest hybridization signals were chosen to study the linkage of individual Z01-A-specific sequences in the genome. Clones were individually labeled and hybridized to 34 Z01-A-specific sequences arrayed as described in Materials and Methods on duplicate nylon membranes. The hybridization results suggested three categories of clones: (i) two clones, one of which was designated FOSU1, overlapped each other as shown by hybridization to 13 sequences, including genes that may be involved in type 1 fimbrial (pilus) synthesis; (ii) four other clones, one of which was designated FOSU2, were shown to be from the same locus, as they all hybridized to seven Z01-A-specific sequences, including five encoding putative phage proteins; (iii) four clones duplicated each other in hybridizing to two Z01-A-specific sequences. Because they contained multiple Z01-A sequences, FOSU1 and FOSU2 were sequenced. Analysis of the FOSU1 sequence revealed at multiple loci a total of 13 transposases from three different insertion sequences (Fig. 1). The average G+C content for FOSU1 was 51.67%, a value much lower than the approximately 59% G+C content calculated for the genome of S. marcescens db11, for which shotgun sequences are available in the Sanger Institute database (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/S_marcescens/). These two features together indicate that much of the FOSU1 locus is likely a genome island obtained by lateral gene transfer. A fimbrial-gene cluster, which may be involved in synthesis of filamentous surface-adhesive organelles called type 1 pili, was identified at the end of the genome island (Fig. 1). Putative proteins encoded by genes within this cluster include the fimbrins FimA and FimI, the adaptor proteins FimG and FimF, the usher proteins FimD and FimC, the adhesin FimH, and the regulatory protein FimE (23). The gene cluster has the same gene organization as other fimbrial-gene clusters from related organisms, except that in S. marcescens Z01-A, the regulatory gene fimE is truncated and fimB is located 21 kb upstream. Interestingly, the G+C content of this gene cluster is only 49.94%, even lower than that of the FOSU1 genome island.

FIG. 1.

Sequence analysis of FOSU1 and its fimbrial-gene cluster. (A) Diagrammatic representation of FOSU1. Gray rectangles represent different transposases. White rectangles represent ORFs of unknown function or structural proteins. (B) Putative ORFs in the fimbrial-gene cluster identified in this study. (C) Putative ORFs in the fimbrial-gene cluster from E. coli O157:H7 EDL933 (upper) and Shigella flexneri 2a str 2457T (lower). (D) G+C content of the fimbrial cluster.

FOSU2 also contained a gene cluster, in which each ORF had a corresponding homolog in the genome of Fels-1, a phage of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 (20). The highest match for each ORF, however, was from various phages, including Fels-1, Gifsy-2 (20), N15 (NCBI reference NP_046907.1), CP933U (23), CP933K (15), and HK97 (16). Interestingly, the location of the FOSU2 homolog in all these phages is within a gene cluster, all of which have genomic architectures similar to one another and to that of the Z01-A FOSU2 gene cluster. The Z01-A gene cluster (prophage), however, lacks a virulence factor, superoxide dismutase SodCIII, that is present in Fels-1. The G+C content of the Z01-A gene cluster is 57.26%, which is close to the 56.46% G+C content of Fels-1 in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 (20).

Location of FOSU1 island on the chromosome.

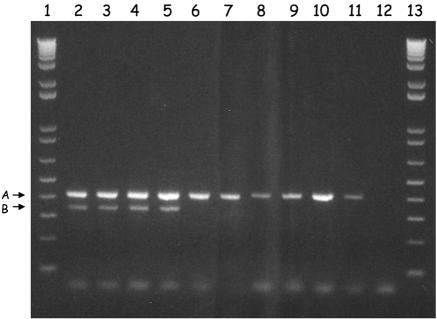

The identification of an ORF putatively encoding a plasmid partitioning protein within the FOSU1 locus raises the question of whether flanking sequences are from a plasmid or from the chromosome. Theoretically, it is possible that a trace amount of plasmid DNA could have remained in the genomic-DNA preparations, and vice versa. However, plasmid DNA would be enriched in the plasmid preparation, and chromosomal DNA would be enriched in the genomic-DNA preparation. In this study, the intensity of the band of an a43 sequence amplified from the genomic-DNA preparation was much greater than that amplified from the plasmid preparation, clearly showing that a43, together with the flanking sequences in FOSU1, is located on the bacterial chromosome (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of 16S rRNA genes (lanes 1 to 5) and sequence a43 (lanes 6 to 10) amplified from a dilution series of genomic DNA (upper picture; 50×, 100×, 200×, 400×, and 800× dilutions of the original isolated DNA solution and plasmid preparations (lower picture; 50×, 100×, 200×, 400×, and 800× dilutions of the original isolated DNA solution).

Conservation of subtracted sequences among S. marcescens strains.

The extent of polymorphism among S. marcescens strains for the subtracted sequences was assessed by dot hybridization. Sequences were arrayed on duplicate nylon membranes and hybridized to different CYVD strains or nonphytopathogenic strains. All 94 sequences hybridized to probes made from genomic DNAs of CYVD strains P01-A, C01-A, W01-A, and W09-A. However, the intensity of the hybridization signal varied among different sequences (data not shown). Forty-nine, 39, and 41 of the total 94 sequences hybridized to rice endophytic strain R01-A, cotton endophytic strain 90-166, and insect pathogenic strain db11, respectively. The conservation of sequences among tested S. marcescens strains varied (Table 3). Thirty-four sequences were present only in strain Z01-A. To confirm the reliability of the hybridization result, all of the sequences were subjected to BLASTN searches against the genome sequences of S. marcescens db11 (Table 3). A homolog with identity greater than 87% was found in the S. marcescens db11 genome database for every Z01-A subtracted sequence that hybridized to the db11 genomic DNA probe. On the other hand, no homolog was found for any of the sequences that were negative for hybridization to db11. Although clone c98 had a match in the db11 database with an expected value of e-19, the identity was only 62%. As expected, clone c98 did not react with the db11 genomic probe.

TABLE 3.

Conservation of tester-specific sequences among Serratia marcescens strains

| Clone | Locationa | Hybridization to bacterial strainsb

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z01-A (CYVD pathogenic) | R02-A (CYVD nonpathogenic) | R01-A (CYVD nonpathogenic) | 90-166 (CYVD nonpathogenic) | Db11 (e-value)c (CYVD nonpathogenic) | ||

| A3 | + | − | − | − | − | |

| A6 | FOSU2 | + | − | − | − | − |

| A13 | + | − | + | − | − | |

| A23 | + | − | + | − | + (e-41) | |

| A27 | FOSU1 | + | − | − | − | − |

| A28 | FOSU1 | + | − | − | − | − |

| A30d | + | − | − | − | − | |

| A33 | + | +− | +− | − | + (e-52) | |

| A40 | + | − | − | + | − | |

| A43 | FOSU1 | + | − | − | − | − |

| A46 | + | − | − | − | − | |

| A48 | FOSU1 | + | − | − | − | − |

| A57 | + | − | − | − | − | |

| A64 | FOSU1 | + | − | − | − | − |

| A66 | + | − | − | − | − | |

| A68 | + | − | − | + | + (e-31) | |

| A71 | + | − | − | + | − | |

| A76 | + | − | − | − | + (e-65) | |

| A79 | Diagnostic marker | + | − | − | − | − |

| A89 | FOSU1 | + | − | − | − | − |

| A99 | + | − | + | + | + (e-55) | |

| B1 | + | − | + | + | + (e-58) | |

| B6 | FOSU1 | + | − | − | − | − |

| B17 | FOSU1 | + | − | − | − | − |

| B21 | + | − | − | − | − | |

| C14 | + | − | + | − | − | |

| C15 | FOSU1 | + | − | − | − | − |

| C19 | + | − | − | − | − | |

| C22 | FOSU2 | + | − | − | − | − |

| C24 | FOSU1 | + | − | − | − | − |

| C25 | FOSU1 | + | − | − | − | − |

| C34 | + | − | − | − | − | |

| C48e | + | − | − | − | − | |

| C63 | FOSU1 | + | − | − | − | − |

| C67 | FOSU2 | + | − | − | − | − |

| C68 | FOSU1 | + | − | − | − | − |

| C69 | + | − | + | − | − | |

| C71 | + | − | − | − | + (e-29) | |

| C89 | FOSU1 | + | − | − | − | − |

| C93 | + | − | − | − | − | |

| C98 | FOSU1 | + | − | − | − | − (e-19) |

| C99 | FOSU2 | + | − | − | − | − |

| D1 | + | − | − | − | − | |

| D2 | FOSU2 | + | − | + | − | − |

| D6 | FOSU1 | + | − | − | − | − |

| D20 | FOSU2 | + | − | − | − | − |

| D21 | + | − | − | + | − | |

| D26 | + | − | − | + | + (e-140) | |

| D37 | FOSU1 | + | − | − | − | − |

Whether the clone was located in FOSU1 or FOSU2.

The designation + indicates positive hybridization, whereas − indicates negative hybridization; the designation +− indicates an ambiguous hybridization signal.

Expected values were obtained by BLASTN search of individual tester-specific sequences against S. marcescens db11 draft sequences.

Clone A30 shares the same insert sequence with clone C26.

Clone C48 shares the same insert sequence with clone C62.

Multiplex PCR diagnosis.

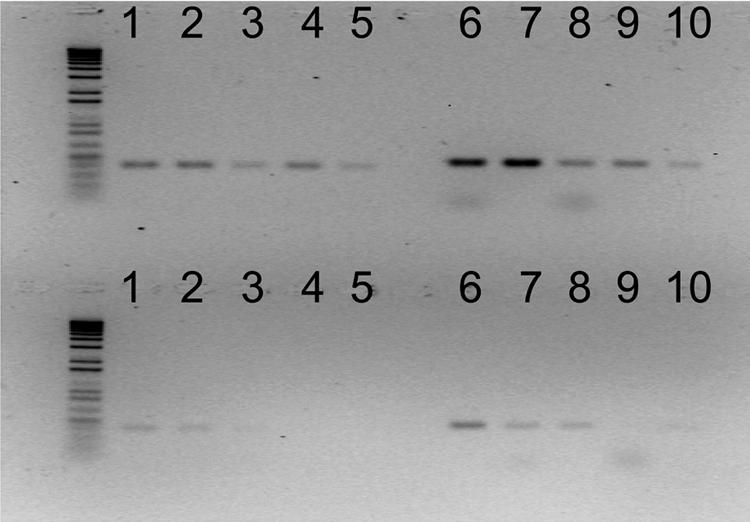

Neither BLASTN nor BLASTX searches of the GenBank database revealed sequence similarity to subtracted Z01-A sequence a79 (Table 2). In addition, the DNA sequence of a79 was negative for hybridization to all tested CYVD nonphytopathogenic strains (Table 3). A new pair of primers, designated a79F (5′-CCAGGATACATCCCATGATGAC-3′) and a79R (5′-CATATTACCTGCTGATGCTCCTC-3′), were designed based on a79. A multiplex PCR was carried out as described in Materials and Methods. A PCR amplicon of 338 bp was amplified from CYVD strains, but not from nonphytopathogenic S. marcescens strains. As a comparison, a 452-bp amplicon was amplified from all S. marcescens strains using primers YV1 and YV4. No fragments were amplified from non-S. marcescens strains (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

CYVD pathogenic (lanes 2 to 5) and nonpathogenic (lanes 6 to 12) strains were detected by multiplex PCR employing primers YV1/4 and a79F/R. (A) 452-bp band amplified by YV1/4. (B) 338-bp band amplified by a79F/R.

DISCUSSION

Results of DNA-DNA hybridizations from a previous study (36) showed that, of all the non-CYVD strains tested, S. marcescens endophytic strain R02-A was most closely related to CYVD strains. With a relative binding ratio of 90% and a 1.5% divergence from the representative CYVD strain C01-A, and confirmed to be nonpathogenic to cucurbits, R02-A is an ideal driver strain to subtract from the well-studied CYVD pathogenic strain Z01-A.

This is the first report of using SSH to identify the genetic differences between S. marcescens strains, which generally have high G+C contents. About 51% of the subtracted differential sequences were confirmed by dot hybridization to be present in Z01-A but absent in R02-A. The reliability of dot hybridization was further validated by hybridization of subtracted Z01-A sequences with S. marcescens db11, in which a hybridization signal always corresponded to >87% sequence identity. In addition, except for istA of IS21, which had a number of copies on the Z01-A genome, all other sequences were represented no more than four times, indicating that the library was not significantly biased (data not shown). Since about half of the differential sequences were represented only once, the potential library of Z01-A-specific DNAs was not exhausted in our experiments.

A large number of subtracted clones identified in this study resembled known genes involved in synthesis of O antigen and type 1 pili, both of which are important bacterial surface structures. O antigen is the outermost component of lipopolysaccharide, the major structural and immunodominant molecule of the outer membrane. In plants the CYVD pathogen investigated in this study lives predominantly in the phloem sieve tubes, a tissue that is rich in nutrients and high in osmotic pressure, and is transmitted by an insect vector, the squash bug (Anasa trisits) (8). Although it is not known whether CYVD strains of S. marcescens can colonize other ecological niches, it certainly is possible. Adaptation to such widely diverse niches might be the driving force for the genetic variation of surface molecules.

The most striking result in this study is the identification of two gene clusters present in CYVD strains of S. marcescens but absent in closely related, but nonphytopathogenic, strains tested. Several lines of evidence suggest that the fimbrial-gene cluster was likely part of a genome island acquired from other species (14): (i) the prevalence of transposases of insertion sequences at the flanking region, (ii) low G+C content, (iii) gene organization similar to that of related bacterial species, and (iv) the presence of the fimbrial-gene cluster only in CYVD strains and not in CYVD nonphytopathogenic strains, as shown by the DNA hybridization. In other bacteria, the whole gene cluster is responsible for the production and control of type 1 fimbriae (32). The adhesin fimH, which is located at the distal tip of the pilus, mediates not only bacterial adherence, but also invasion of human bladder epithelial cells (18). The expression of pilins, however, could be turned on and off by site-specific DNA inversion of a 312-bp fragment containing the promoter region of fimA (31) through a process catalyzed by two recombinases, FimB and FimE. Our work showed that Z01-A had only a truncated version of fimE, and that fimB is located 21 kb further upstream of the gene cluster in Z01-A than it is in other bacteria. These features would impact the production of type 1 pili. In a separate experiment, pilus-like structures were observed in Z01-A, but not in R02-A, using transmission electron microscopy (data not shown). In the future, further electron microscopic observation, fimbrial-gene cluster knockout, and complementation experiments should provide evidence of whether this cluster of genes contributes to CYVD strain pathogenicity.

We also studied the distribution of the subtracted sequences, including the two gene clusters, among CYVD strains isolated from different cucurbit species and among nonphytopathogenic strains from various niches. All CYVD strains tested were positive by hybridizations for the subtracted sequences with various degrees of intensity, consistent with their average 99% relatedness determined in a DNA-DNA hybridization study (36). The three non-CYVD S. marcescens strains, on the other hand, each hybridized to a distinct portion of the subtracted Z01-A sequences. Notably, R01-A and R02-A shared the greatest number of common sequences among the CYVD nonpathogenic strains (data not shown), confirming the close relatedness of these strains to Z01-A, which was predicted earlier from DNA-DNA hybridization and repetitive extragenic palindromic PCR experiments (36). Testing the hybridization of the subtracted sequences to a more extensive set of S. marcescens strains might reveal more genetic variations that underlie the evolutionary process.

SSH proved to be a useful method for identifying molecular markers for epidemiological studies and diagnosis. When choosing the markers, we purposely avoided the two gene cluster regions, as the occurrence of gene transfer among related bacterial species could complicate marker identification. Using a primer pair designed based on a subtracted Z01-A-specific sequence, a79, we were able to differentiate CYVD strains from nonphytopathogenic strains of S. marcescens. The selected marker is likely to be specific, as it has no sequence similarity, at either the DNA or the translated-protein level, with any sequence in GenBank. The multiplex PCR technique, which includes a primer pair to detect the bacterium at the species level, added further reliability to the new diagnostic tool. In the future, it can be used in vector identification, field disease diagnoses, and contamination-free examination in the laboratory.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Oklahoma State University Targeted Research Initiative Program; the Oklahoma Agricultural Experiment Station, project 2092; and the USDA Southern Regional IPM Program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agron, P. G., M. Macht, L. Radnedge, E. W. Skowronski, W. Miller, and G. L. Andersen. 2002. Use of subtractive hybridization for comprehensive surveys of prokaryotic genome differences. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 211:175-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and, K. Struhl. 1987. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. John Wiley & Sons, New York, N.Y.

- 3.Ayoubi, P., X. Jin, S. Leite, X. Liu, J. Martajaja, A. Abduraham, Q. Wan, W. Yan, E. Misawa, and R. A. Prade. 2002. PipeOnline 2.0: automated EST processing and functional data sorting. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:4761-4769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodenteich, A., S. Chissoe, Y. F. Wang, and B. A. Roe. 1993. Shotgun cloning as the strategy of choice to generate templates for high-throughput dideoxynucleotide sequencing, p. 42-50. In J. C. Venter (ed.), Automated DNA sequencing and analysis techniques. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom.

- 5.Bost, S. C., F. L. Mitchell, U. Melcher, S. D. Pair, J. Fletcher, A. Wayadande, and B. D. Bruton. 1999. Yellow vine of watermelon and pumpkin in Tennessee. Plant Dis. 83:587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruton, B. D., J. Fletcher, S. D. Pair, M. Shaw, and H. Sittertz-Bhatkar. 1998. Association of a phloem-limited bacterium with yellow vine disease in cucurbits. Plant Dis. 82:512-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruton, B. D., S. D. Pair, T. W. Popham, and B. O. Cartwright. 1995. Occurrence of yellow vine, a new disease of squash and pumpkin, in relation to insect pests, mulches, and soil fumigation. Subtrop. Plant Sci. 47:53-58. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruton, B. D., F. Mitchell, J. Fletcher, S. D. Pair, A. Wayadande, U. Melcher, J. Brady, B. Bextine, and T. W. Popham. 2003. Serratia marcescens, a phloem-colonizing, squash bug-transmitted bacterium: causal agent of cucurbit yellow vine disease. Plant Dis. 87:937-944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bugert, P., and K. Geider. 1997. Characterization of the amsI gene product as a low molecular weight acid phosphatase controlling exopolysaccharide synthesis of Erwinia amylovora. FEBS Lett. 400:252-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chissoe, S. L., A. Bodenteich, Y. F. Wang, Y. P.Wang, C. Burian, S. W. Dennis, J. Crabtree, A. Freeman, K. Iyer, L. Jian, Y. Ma, H. J. McLaury, H. Q. Pan, O. Sharan, S. Toth, Z. Wong, G. Zhang, N. Heisterkamp, J. Groffen, and B. A. Roe. 1995. Sequence and analysis of the human ABL gene, the BCR gene, and regions involved in the Philadelphia chromosomal translocation. Genomics 27:67-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ewing, B., L. Hillier, M. Wendl, and P. Green. 1998. Basecalling of automated sequencer traces using phred. I. Accuracy assessment. Genome Res. 8:175-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ewing, B., and P. Green. 1998. Basecalling of automated sequencer traces using phred. II. Error probabilities. Genome Res. 8:186-194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon, D., C. Abajian, and P. Green. 1998. Consed: a graphical tool for sequence finishing. Genome Res. 8:195-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hacker, J., and J. B. Kaper. 2000. Pathogenicity islands and the evolution of microbes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:641-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin, Q., Z. Yuan, J. Xu, Y. Wang, Y. Shen, W. Lu, J. Wang, H. Liu, J. Yang, F. Yang, X. Zhang, J. Zhang, G. Yang, H. Wu, D. Qu, J. Dong, L. Sun, Y. Xue, A. Zhao, Y. Gao, J. Zhu, B. Kan, K. Ding, S. Chen, H. Cheng, Z. Yao, B. He, R. Chen, D. Ma, B. Qiang, Y. Wen, Y. Hou, and J. Yu. 2002. Genome sequence of Shigella flexneri 2a: insights into pathogenicity through comparison with genomes of Escherichia coli K12 and O157. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:4432-4441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juhala, R. J., M. E. Ford, R. L. Duda, A. Youlton, G. F. Hatfull, and R. W. Hendrix. 2000. Genomic sequences of bacteriophages HK97 and HK022: pervasive genetic mosaicism in the lambdoid bacteriophages. J. Mol. Biol. 299:27-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lazar, S. W., and R. Kolter. 1996. SurA assists the folding of Escherichia coli outer membrane proteins. J. Bacteriol. 178:1770-1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinez, J. J., M. A. Mulvey, J. D. Schilling, J. S. Pinkner, and S. J. Hultgren. 2000. Type 1 pilus-mediated bacterial invasion of bladder epithelial cells. EMBO J. 19:2803-2812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mavrodi, D. V., O. V. Mavrodi, B. B. McSpadden-Gardener, B. B. Landa, D. M. Weller, and L. S. Thomashow. 2002. Identification of differences in genome content among phlD-positive Pseudomonas fluorescens strains by using PCR-based subtractive hybridization. Appl. Environ Microbiol. 68:5170-5176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McClelland, M., K. E. Sanderson, J. Spieth, S. W. Clifton, P. Latreille, L. Courtney, S. Porwollik, J. Ali, M. Dante, F. Du, S. Hou, D. Layman, S. Leonard, C. Nguyen, K. Scott, A. Holmes, N. Grewal, E. Mulvaney, E. Ryan, H. Sun, L. Florea, W. Miller, T. Stoneking, M. Nhan, R. Waterston, and R. K. Wilson. 2001. Complete genome sequence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2. Nature 413:852-856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melcher, U., F. Mitchell, J. Fletcher, and B. Bruton. 1999. New primer sets distinguish the cucurbit yellow vine bacterium from an insect endosymbiont. Phytopathology 89:S95. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pan, H. Q., Y. P. Wang, S. L. Chissoe, A. Bodenteich, Z. Wang, K. Iyer, S. W. Clifton, J. S. Crabtree, and B. A. Roe. 1994. The complete nucleotide sequence of the SacBII domain of the P1 pAD10-SacBII cloning vector and three cosmid cloning vectors: pTCF, svPHEP, and LAWRIST16. Genet. Anal. Tech. Appl. 11:181-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perna, N. T., G. Plunkett III, V. Burland, B. Mau, J. D. Glasner, D. J. Rose, G. F. Mayhew, P. S. Evans, J. Gregor, H. A. Kirkpatrick, G. Posfai, J. Hackett, S. Klink, A. Boutin, Y. Shao, L. Miller, E. J. Grotbeck, N. W. Davis, A. Lim, E. T. Dimalanta, K. D. Potamousis, J. Apodaca, T. S. Anantharaman, J. Lin, G. Yen, D. C. Schwartz, R. A. Welch, and F. R. Blattner. 2001. Genome sequence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Nature 409:529-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rascoe, J., M. Berg, U. Melcher, F. Mitchell, B. D. Bruton, S. D. Pair, and J. Fletcher. 2003. Identfication, phylogenetic analysis and biological characterization of Serratia marcescens causing cucurbit yellow vine disease. Phytopathology 93:1233-1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reimmann, C., R. Moore, S. Little, A. Savioz, N. S. Willetts, and D. Haas. 1989. Genetic structure, function and regulation of the transposable element IS21. Mol. Gen. Genet. 215:416-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roe, B. A. 2004. Shotgun library construction for DNA sequencing, p. 171-187. In S. Zhao and M. Stodolsky (ed.), Methods in molecular biology, vol 255: Bacterial artificial chromosomes, vol. 1: Library construction, physical mapping, and sequencing. Humana Press Inc., Totowa, N.J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rozen, S., and H. Skaletsky. 2000. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol. Biol. 132:365-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rutherford, K., J. Parkhill, J. Crook, T. Horsnell, P. Rice, M.-A. Rajandream, and B. Barrell. 2000. Artemis: sequence visualisation and annotation. Bioinformatics 16:944-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saigi, F., N. Climent, N. Pique, C. Sanchez, S. Merino, X. Rubires, A. Aguilar, J. M. Tomas, and M. Regue. 1999. Genetic analysis of the Serratia marcescens N28b O4 antigen gene cluster. J. Bacteriol. 181:1883-1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook, J. E., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 31.Sohanpal, B. K., H. D. Kulasekara, A. Bonnen, and I. C. Blomfield. 2001. Orientational control of fimE expression in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 42:483-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soto, G. E., and S. J. Hultgren. 1999. Bacterial adhesins: common themes and variations in architecture and assembly. J. Bacteriol. 181:1059-1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sydenham, M., G. Douce, F. Bowe, S. Ahmed, S. Chatfield, and G. Dougan. 2000. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium surA mutants are attenuated and effective live oral vaccines. Infect. Immun. 68:1109-1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wick, R. L., J. Lernal, J. Fletcher, F. Mitchell, and B. D. Bruton. 2001. Detection of cucurbit yellow vine disease in squash and pumpkin in Massachusetts. Plant Dis. 85:1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winstanley, C. 2002. Spot the difference: applications of subtractive hybridisation to the study of bacterial pathogens. J. Med. Microbiol. 51:459-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang, Q., R. Weyant, A. G. Steigerwalt, L. A. White, U. Melcher, B. D. Bruton, S. D. Pair, F. L. Mitchell, and J. Fletcher. 2003. Genotyping of Serratia marcescens strains associated with cucurbit yellow vine disease by repetitive elements-based polymerase chain reaction and DNA-DNA hybridization. Phytopathology 93:1240-1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]