Abstract

To date, expression of the lipase from Rhizopus oryzae (ROL) in Escherichia coli always led to the formation of inclusion bodies and inactive protein. However, the production of active ROL and its precursor ProROL in soluble form was achieved when E. coli Origami(DE3) and pET-11d were used as expression systems.

Lipases (triacylglycerol ester hydrolases; E.C. 3.1.1.3) have multiple applications in a wide range of biotechnological processes (11, 13, 19, 20, 25). Lipases from the genus Rhizopus are attractive catalysts in lipid modification processes, since they are active only against esters of primary alcohols and positionally selective, acting only at the sn1 and sn3 locations (2). Both the structure (5, 22) and function of the lipase from the fungus Rhizopus oryzae ATCC 34612 (formerly Rhizopus delemar) (18) have been deeply investigated. The Rhizopus delemar lipase is initially synthesized as a preproenzyme, consisting of the 269 amino acids of the mature enzyme, a 97-amino-acid propeptide fused to its amino terminus, and a 26-amino-acid-long export signal peptide at the amino terminus of the propeptide (8). Additionally, it contains six cysteine residues, which form three disulfide bridges (6). Since Escherichia coli lacks the necessary proteases to process fungal maturation signals, the Rhizopus delemar lipase cDNAs were previously expressed in E. coli for both the unprocessed lipase precursor and the mature product in insoluble form (10). The production of an active mature Rhizopus lipase has been performed in Pichia pastoris (4, 14) and in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (23).

In this work we present, for the first time, the expression of the Rhizopus oryzae lipase gene in E. coli to yield a correctly folded product, present only in the cytoplasm fraction.

Methods, results, and discussion.

Cloning of the cDNA coding for the prolipase and mature lipase from the fungus Rhizopus delemar (renamed as Rhizopus oryzae in accordance with the literature [18]) in pET11-d has been previously reported (15). E. coli strain DH5α [supE44 dlacU169(φ80lacZΔM15)hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1] was used as host for genetic manipulation of plasmids. E. coli BL21(DE3) [F− ompT hsdSB(rB− mB) gal dcm (DE3)], Rosetta(DE3)[F− ompT hsdSB(rB− mB) gal dcm (DE3) pRARE2 (Cmr)] and Origami(DE3) [Δara-leu7697 dlacX74 ΔphoAPvuII phoR araD139 ahpC galE galK rpsL (Smr)4F1 [lac+(lacIq) pro] gor522::Tn10 (Tcr) trxB::kan (DE3)] strains were used for the overexpression of proteins. The E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani medium containing 100 mg/liter ampicillin, 30 mg/liter kanamycin, 10 mg/liter tetracycline, 34 mg/liter chloramphenicol, as required. Plasmids pET-11d, pET-15b, pET-28b(+), and pET-22b(+) (Novagen) were used for cloning and protein expression. Transformation of E. coli was performed as described previously (9). All molecular biology protocols were performed using standard methods (17).

For PCR amplification of the genes of interest, the following oligonucleotides were used: 1F (5′-AAGGAGATATCATATGGTTCCTGT-3′), 2F (5′-GAGATATCATATGGATGGTGGTA-3′), and 3R (5′-AACACGTCAAGAATTCTTCAAACA-3′) (underlined portions of sequences are NdeI restriction sites introduced for cloning purposes). To obtain an N-terminal His-tagged product, the prolipase and mature lipase genes were amplified by PCR by using, respectively, oligonucleotides 1F or 2F and the T7 terminator primer. To obtain a C-terminal His-tagged product, the amplification by PCR was also performed with primer 1F or 2F and primer 3R.

The PCR products were purified and digested with NdeI and EcoRI and ligated into pET-28b(+) and pET-22b(+) vectors. The pET-28b(+) constructs carrying the prolipase and mature lipase genes were digested with NdeI and XhoI, purified, and ligated into the empty pET-15b vector. To evaluate the influence of the His tag on expression, the prolipase gene preceded by a six-His tag sequence was cloned into pET-11d. For this purpose the pET-15b vector containing the prolipase gene was digested with NcoI and BamHI, and the fragment was purified and ligated into the pET-11d vector.

The E. coli strains harboring the pET recombinant plasmids were grown in 100 ml Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with the required antibiotics using isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside as inducer to a final concentration of 0.1 mM. At different time intervals, aliquots (equivalent to 5 ml at an optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of 1) were centrifuged for 10 min at 800 × g to harvest the cells. The cells were then resuspended in 300 μl 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, and disrupted by sonication (20 s, 50% pulse). The soluble fraction and the particulate material were separated by centrifugation, and 10 μl from these preparations was analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on 12% polyacrylamide gels and stained with Coomassie blue, as described by Laemmli (12). The soluble fraction was also subjected to activity measurement by monitoring the amount of p-nitrophenol released upon hydrolysis of a 1 mM solution of p-nitrophenylbutyrate in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.5 at room temperature. Aliquots (100 μl) of the cell fraction assayed were added to 900 μl of the reaction mixture, and the increase in absorbance at 410 nm was measured for 1 min. One unit of hydrolase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme releasing 1 μmol of p-nitrophenol per min at room temperature. The protein concentration of the samples was determined according to the method of Bradford (3).

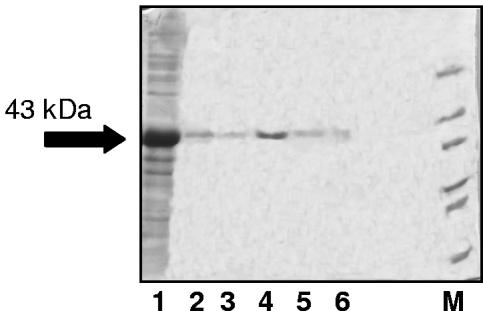

The expression of the pET-11d prolipase and mature lipase constructs in E. coli BL21(DE3) or Rosetta led to an insoluble and inactive product (data not shown). The insoluble protein pellet obtained from a 100-ml culture was resuspended in 15 ml of 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, incubated at 37°C for 10 min, centrifuged at 16,000 × g, and washed with 20 ml of 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.5. The inclusion bodies were resuspended in 2 ml of sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7, containing 8 M urea and incubated at 37°C for 20 min. The total sample volume was then purified with 2 ml of Talon cellThru IMAC resin (BD Biosciences, Palo Alto, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions in the presence of 8 M urea (Fig. 1). The eluted fractions containing the target protein were pooled, concentrated, and refolded according to a previously described protocol (7). The purified prolipase was refolded in the presence of cysteine, leading to an active enzyme preparation (0.645 U/ml). Unfortunately, the enzyme was inactivated after storage of the refolded protein either at −20°C, at 4°C, or when lyophilized.

FIG. 1.

Purification of the prolipase from inclusion bodies with a cobalt-based resin. Lane 1, pellet solution; lanes 2 and 3, washings; lanes 4, 5, and 6, elution; lane M, molecular mass marker (66, 45, 36, 29, 24, and 20.1 kDa). Ten-microliter aliquots of the soluble and insoluble fraction samples, prepared as described in the text, were loaded onto each lane. The arrow indicates the prolipase.

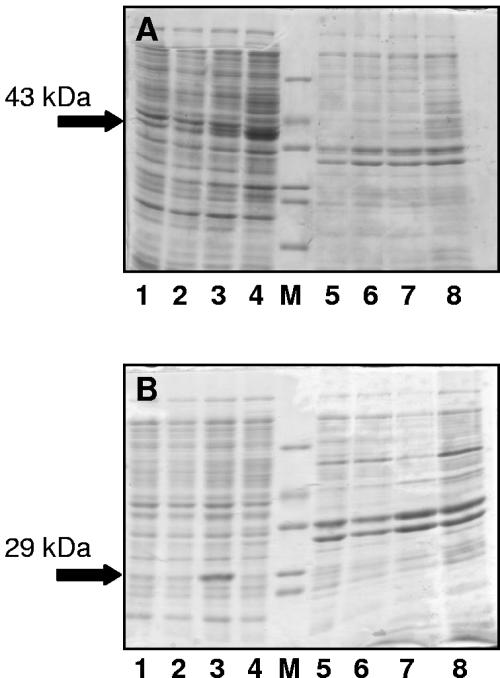

When the E. coli Origami(DE3) strain was used, the expression was successful and the target protein was expressed as soluble and active forms (Fig. 2A and B). Although their specific activities are comparable, the yield of prolipase was higher than for the mature lipase, probably due to the toxicity of the latter towards the host cells (8). The prosequence has been reported to modulate the enzyme activity of the mature lipase so that it can be synthesized without damaging the host, in this case as a result of a decreased affinity of the prolipase for phospholipids in comparison to the mature lipase (1). This modulation also causes the prolipase and the mature lipase to have different affinities for their substrates (24), although whether this is caused by an interaction between the prosequence and the peptide lid that sits atop the active site in an inactive form of the mature enzyme (5) has not been confirmed, since a resolved crystal structure of the prolipase is not available. However, the fact that the prolipase is active implies that the part of the expression product corresponding to the mature peptide is already correctly folded.

FIG. 2.

A. Expression at 25°C of E. coli Origami harboring the pET11-d prolipase. Lane 1, prolipase before induction, supernatant; lane 2, prolipase after 1 h of induction, supernatant; lane 3, prolipase after 3 h of induction, supernatant; lane 4, prolipase after 24 h of induction, supernatant; lane M, molecular mass marker (66, 45, 36, 29, 24, and 20.1 kDa); lane 5, prolipase before induction, pellet; lane 6, prolipase after 1 h of induction, pellet; lane 7, prolipase after 3 h of induction, pellet; lane 8, prolipase after 24 h of induction, pellet. Ten microliters of the soluble and insoluble fraction samples, prepared as described in the text, was loaded onto each lane. The arrow indicates the prolipase. B. Expression at 25°C of E. coli Origami harboring the pET11-d mature lipase. Lane 1, lipase before induction, supernatant; lane 2, lipase after 1 h of induction, supernatant; lane 3, lipase after 3 h of induction, supernatant; lane 4, lipase after 24 h of induction, supernatant; lane M, molecular mass marker (66, 45, 36, 29, 24, and 20.1 kDa); lane 5, lipase before induction, pellet; lane 6, lipase after 1 h of induction, pellet; lane 7, lipase after 3 h of induction, pellet; lane 8, lipase after 24 h of induction, pellet. Ten microliters of the soluble and insoluble fraction samples, prepared as described in the text, was loaded onto each lane. The arrow indicates the mature lipase.

In order to improve the amount of prolipase produced, several temperatures and cell densities at the time of induction were analyzed (Table 1). Only at 25°C and 20°C was an active product obtained, and under optimal conditions, the expression of E. coli Origami pET-11d prolipase gave 110.7 U/mg, at a growth temperature of 20°C with induction at an OD600 of 1. Although the functional expression of Rhizopus sp. lipase has been already performed in Pichia pastoris (14-16) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (21, 23), we hesitate to compare the data, as different activity assays with different substrates and conditions have been used. In addition, the productivity is difficult to compare, as a system using Pichia pastoris has the advantage—in contrast to an E. coli expression system—that the lipase is in the supernatant and cell disruption is not necessary, but the enzyme is highly diluted. On the other hand, high-cell-density cultivation of E. coli can also yield large amounts of recombinant protein, and no background lipase (or esterase) activity is present in crude cell extracts. Thus, a purification of the lipase is not necessary.

TABLE 1.

Influence of growth temperature and OD600 of induction on yield of prolipase from R. oryzae produced in E. coli Origami (pET 11-d construct)

| Growth temp (°C) | OD600 at induction | Activitya (U/ml) | Protein concn (mg/ml) | Sp act (U/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 0.5 | 40.7 | 0.7 | 60.4 |

| 20 | 1 | 166 | 1.5 | 110.7 |

| 25 | 0.5 | 45.1 | 0.95 | 47.3 |

| 25 | 1 | 28.4 | 0.7 | 42.4 |

Determined using p-nitrophenyl butyrate as substrate.

The influences of several vectors in the prolipase production were studied too. pET15 and pET22 were considered for a simplified purification of the His-tagged, recombinant product. The expressions were performed at 20°C and at OD600 values of 1 and 0.5. A deeper evaluation of the influence of the His tag on the expression was carried out by cloning the prolipase gene preceded by a six-His tag sequence into vector pET-11d and comparing the expression results between this construct and that without an N-terminal His tag. Table 2 shows that the His tag in the N-terminal position negatively influenced the protein activity. On the other hand, the His tag in the C-terminal position did not influence the activity. The fact that the C-terminal position of the His tag does not have an effect on activity, while the N-terminal markedly does, may be related to the role of the N-terminal prosequence as an intramolecular chaperone assisting in the folding of the mature peptide. Although no structural data on the prolipase are available, it seems logical that the environment of the prosequence should be kept as unmodified as possible, since it has been previously reported to influence the formation of disulfide bonds (1).

TABLE 2.

Influence of vector and OD600 at induction time on activity of prolipase from R. oryzae expressed in E. coli Origami at 20°C

| Vector | OD600 at induction | Activitya (U/ml) | Protein concn (mg/ml) | Sp act (U/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pET11 | 0.5 | 40.7 | 0.7 | 60.4 |

| pET11 | 1 | 166 | 1.5 | 110.7 |

| pET15 | 0.5 | 53.1 | 1.6 | 32.5 |

| pET15 | 1 | 35.7 | 0.875 | 40.8 |

| pET11 + His tag | 0.5 | 34 | 1.64 | 20.7 |

| pET11 + His tag | 1 | 33 | 1.75 | 18.8 |

| pET22 | 0.5 | 82 | 0.7 | 116 |

| pET22 | 1 | 50 | 0.7 | 70.7 |

Determined using p-nitrophenyl butyrate as substrate.

In summary, we have demonstrated that the lipase from Rhizopus oryzae can now be functionally expressed in E. coli without the need for inclusion body purification and a tedious refolding process. The prolipase could be efficiently produced in high yield at high specific activity.

Acknowledgments

A. Hidalgo acknowledges the financial support provided through the European Community's Human Potential Programme under contract HPRN-CT2002-00239.

M. Di Lorenzo thanks D. Pirozzi and G. Greco for giving her the possibility to work in Germany.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beer, H. D., G. Wohlfahrt, R. D. Schmid, and J. E. G. McCarthy. 1996. The folding and activity of the extracellular lipase of Rhizopus oryzae are modulated by a prosequence. Biochem. J. 319:351-359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bornscheuer, U. T., J. Pleiss, C. Schmidt-Dannert, and R. D. Schmid. 2000. Lipases from Rhizopus species: genetics, structures and applications, p. 115-134. In L. Alberghina (ed.), Protein engineering in industrial biotechnology. Harwood Academic Publishers, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 3.Bradford, M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cos, O., A. Serrano, J. L. Montesinos, P. Ferrer, J. M. Cregg, and F. Valero. 2005. Combined effect of the methanol utilization (Mut) phenotype and gene dosage on recombinant protein production in Pichia pastoris fed-batch cultures. J. Biotechnol. 116:321-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Derewenda, U., L. Swenson, R. Green, Y. Wei, S. Yamaguchi, R. D. Joerger, M. J. Haas, and Z. S. Derewenda. 1994. Current progress in crystallographic studies of new lipases from filamentous fungi. Prot. Eng. 7:551-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Derewenda, U., L. Swenson, Y. Wei, R. Green, P. M. Kobos, R. D. Joerger, M. J. Haas, and Z. S. Derewenda. 1994. Conformational lability of lipases observed in the absence of an oil-water interface: crystallographic studies of enzymes from the fungi Humicola lanuginosa and Rhizopus delemar. J. Lipid Res. 35:524-534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haas, M. J., J. Allen, and T. R. Berka. 1991. Cloning, expression and characterization of a cDNA encoding a lipase from Rhizopus delemar. Gene 109:107-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haas, M. J., D. G. Bailey, W. Baker, T. R. Berka, D. J. Cichowicz, Z. S. Derewenda, R. R. Genuario, R. D. Joerger, R. R. Klein, K. Scott, and D. Woolf. 1999. Biochemical and molecular characterization of a lipase produced by the fungus Rhizopus delemar. Fett Lipid 101:364-370. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanahan, D. 1983. Studies on the transformation of E. coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 166:557-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joerger, R. D., and M. J. Haas. 1993. Overexpression of a Rhizopus delemar lipase gene in Escherichia coli. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 28:81-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kazlauskas, R. J., and U. T. Bornscheuer. 1998. Biotransformation with lipases, p. 37-191. In D. R. Kelly (ed.), Biotransformations I, 2nd ed., vol. 8a. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of the bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsumoto, T., S. Takahashi, M. Kaieda, M. Ueda, A. Tanaka, H. Fukuda, and A. Kondo. 2001. Yeast whole-cell biocatalyst constructed by intracellular overproduction of Rhizopus oryzae lipase is applicable to biodiesel fuel production. Appl. Microbiol. Technol. 57:515-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minning, S., C. Schmidt-Dannert, and R. D. Schmid. 1998. Functional expression of Rhizopus oryzae lipase in Pichia pastoris: high-level production and some properties. J. Biotechnol. 66:147-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minning, S., A. Serrano, P. Ferrer, C. Solá, R. D. Schmid, and F. Valero. 2001. Optimization of the high-level production of Rhizopus oryzae lipase in Pichia pastoris. J. Biotechnol. 86:59-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Resina, D., A. Serrano, F. Valero, and P. Ferrer. 2004. Expression of a Rhizopus oryzae lipase in Pichia pastoris under control of the nitrogen source-regulated formaldehyde dehydrogenase promoter. J. Biotechnol. 109:103-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 18.Schipper, M. A. A. 1984. A revision of the genus Rhizopus II: the Rhizopus stolonifer group and Rhizopus oryzae. Stud. Mycol. 25:1-19. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmid, R. D., and R. Verger. 1998. Lipases: interfacial enzymes with attractive applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 37:1608-1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmid, U., U. T. Bornscheuer, M. M. Soumanou, G. P. McNeill, and R. D. Schmid. 1999. Highly selective synthesis of 1,3-oleoyl-2-palmitoylglycerol by lipase catalysis. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 64:678-684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shiraga, S., M. Ueda, S. Takahashi, and A. Tanaka. 2002. Construction of the combinatorial library of Rhizopus oryzae lipase mutated in the lid domain by displaying on yeast cell surface. J. Mol. Catal. B 17:167-173. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swenson, L., R. Green, R. D. Joerger, M. J. Haas, K. Scott, Y. Wei, U. Derewenda, D. M. Lawson, and Z. S. Derewenda. 1994. Crystallization and preliminary crystallographic studies of the precursor and mature forms of a neutral lipase from the fungus Rhizopus delemar. Proteins 18:301-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takahashi, S., M. Ueda, H. Atomi, H. D. Beer, U. T. Bornscheuer, R. D. Schmid, and A. Tanaka. 1998. Extracellular production of active Rhizopus oryzae lipase by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 86:164-168. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takahashi, S., M. Ueda, and A. Tanaka. 1999. Independent production of two molecular forms of a recombinant Rhizopus oryzae lipase by KEX2-engineered strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Microbiol. Technol. 52:534-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanaka, M., Y. Norimine, T. Fujita, H. Suemune, and K. Sakai. 1996. Chemoenzymatic synthesis of antiviral carbocyclic nucleosides: asymmetric hydrolysis of meso-3,5-bis(acetoxymethyl)cyclopentenes using Rhizopus delemar lipase. J. Org. Chem. 61:6952-6957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]