Abstract

The phylogeny and evolution of the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis is still poorly understood despite the application of a variety of molecular techniques. We analyzed 469 M. tuberculosis and 49 Mycobacterium bovis isolates to evaluate if the mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units-variable-number tandem repeats (MIRU-VNTR) commonly used for epidemiological studies can define the phylogeny of the M. tuberculosis complex. This population was characterized by previously identified silent single-nucleotide polymorphisms (sSNPs) or by a macroarray based on these sSNPs that was developed in this study. MIRU-VNTR phylogenetic codes capable of differentiating between phylogenetic lineages were identified. Overall, there was 90.9% concordance between the lineages of isolates as defined by the MIRU-VNTR and sSNP analyses. The MIRU-VNTR phylogenetic code was unique to M. bovis and was not observed in any M. tuberculosis isolates. The codes were able to differentiate between different M. tuberculosis strain families such as Beijing, Delhi, and East African-Indian. Discrepant isolates with similar but not identical MIRU-VNTR codes often displayed a stepwise trend suggestive of bidirectional evolution. A lineage-specific panel of MIRU-VNTR can be used to subdivide each lineage for epidemiological purposes. MIRU-VNTR is a valuable tool for phylogenetic studies and could define an evolutionarily uncharacterized population of M. tuberculosis complex organisms.

Despite the application of several molecular markers, relatively little is known about the evolution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (3, 5, 10, 27), the bacterial species which causes 2 million deaths and 8 million new cases annually (8, 25).

Genotyping techniques based on neutral genetic variation such as multilocus sequence typing (MLST) have been used successfully to characterize bacterial populations (6, 9, 15, 20). Although the M. tuberculosis genome is thought to be highly conserved (23, 28), sufficient neutral variation was found within genes associated with drug resistance in M. tuberculosis complex isolates for construction of a robust phylogenetic tree, demonstrating that M. tuberculosis is clonal and is subdivided into four distinct lineages while Mycobacterium bovis is closely related but is found on a separate branch (1).

MIRU-VNTR (mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units-variable-number tandem repeats) is a high-throughput technique that analyzes the number of tandem repeats at loci distributed around the M. tuberculosis genome (30). Studies have explored MIRU-VNTR as a tool for discriminating between strains and in comparison with other molecular techniques (4, 16, 19, 21, 26, 30), but there are few published reports on the use of MIRU-VNTR to study the evolution of the M. tuberculosis complex. VNTR analysis using 5-locus and 12-locus MIRU has been used in combination with other techniques such as spoligotyping to investigate the evolution of M. tuberculosis complex (11, 17, 27), but to our knowledge, no studies have utilized 15-locus MIRU-VNTR to define evolutionary pathways characterized by silent single-nucleotide polymorphism (sSNP) analysis.

Based on the sSNP-defined phylogenetic tree (1), we evaluate the use of MIRU-VNTR, commonly used in epidemiological investigations, as a rapid tool for the phylogenetic classification of M. tuberculosis and M. bovis. To validate the MIRU-VNTR phylogenetic classification, an additional panel of M. tuberculosis and M. bovis strains was characterized with an sSNP macroarray tool (the development of which is described here) and concordance with MIRU-VNTR was examined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mycobacterial strains.

A panel (panel 1, test population) of 312 M. tuberculosis clinical isolates collected in England and Wales between 1 January and 31 December 1998, which included all isolates resistant to one or both of the first-line antituberculous drugs (isoniazid and rifampin) and 100 randomly chosen fully susceptible isolates, as well as 4 M. bovis isolates (1), was typed using MIRU-VNTR (12 MIRU plus exact tandem repeats [ETR] A, B, and C; the two remaining ETR, D and E, are included within the 12 MIRU and correspond to MIRU 4 and 31). All members of this panel had previously been classified into one of five lineages according to the presence of four characteristic sSNPs (1). The laboratory reference strain M. tuberculosis H37Rv (which had been characterized by sSNPs) was also MIRU-VNTR typed.

A second panel (panel 2, validating population) of 205 isolates containing an additional 80 M. tuberculosis isolates from 1998 and 80 isolates from 2004, both collected in England and Wales (two different time windows were chosen to ensure that the results seen were reproducible and not unique to 1998, the year in which the panel 1 strains were isolated), and 45 M. bovis isolates from a panel previously described (14), were analyzed using MIRU-VNTR loci. The M. tuberculosis isolates were all randomly chosen from 1998 and 2004. The M. bovis strains included all available isolates between 1997 and 2001 collected at the Health Protection Agency National Mycobacterium Reference Unit (HPA-MRU). Panel 2 was characterized with a macroarray developed in this study to define sSNPs seen in each of the five lineages. The validation was performed blinded. Results were compared only once a lineage based on each technique had been determined.

Validation of the macroarray.

The macroarray was validated on a subpanel of 46 previously genotyped isolates from panel 1 (1).

MIRU-VNTR analysis.

Twelve-MIRU fragment analysis was carried out on a CEQ2000 DNA capillary sequencer (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, Calif.) as described previously (19) and was supplemented with three loci: ETR-A, ETR-B, and ETR-C (13). Three capillaries were used per isolate. Capillary 1 was used for MIRU-4 and -16 (dye 2), MIRU-2 and -24 (dye 3), and MIRU-10 and -23 (dye 4). Capillary 2 was used for MIRU-39 and ETR-A (dye 2), MIRU-27 and ETR-B (dye 3), and MIRU-31 and -40 (dye 4). Capillary 3 was used for MIRU-20 (dye 2), MIRU ETR-C (dye 3), and MIRU-26 (dye 4). MIRU-VNTR profiles were analyzed using a categorical similarity coefficient (which scores all characters equally and considers any different state as no match and any instance of the same state as a full match) and were displayed using the unweighted-pair group method using average linkages.

DNA macroarray.

Biotin-labeled primers, based on the published sequences of M. tuberculosis H37Rv and CDC1551, were designed to flank the four sSNPs of interest (in oxyR, katG, and rpoB) (Table 1). PCR was carried out in a final volume of 21.2 μl, containing 5 μl sterile distilled water, 10 μl 2× reaction buffer (3 mM MgCl2, 3.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 2× NH4 buffer), 5 μl of primer mix (2 μM each primer), 0.2 μl Taq polymerase (5 U/μl; Bioline, London, United Kingdom), and 1 μl template DNA. Amplification was performed in 0.2-μl thin-walled 96-well plates (Alpha, Eastleigh, United Kingdom) in a Perkin-Elmer Cetus 9600 Thermocycler with the following program: 3 min at 95°C, followed by 30 cycles of 15 s at 95°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 1 min at 72°C, and one final cycle of 5 min at 72°C.

TABLE 1.

Primer sequences for the macroarray

| Gene | Primers (5′-3′) | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| oxyR | ATCGCCGCCAAGAGGTGCTA | 311 |

| TCACGCACTGCACGACGGT | ||

| katG | TGTCCCGTCGTGGGTCATAT | 370 |

| TTGTCCAAGCTGGCGTTGT | ||

| rpoB | TGCGTGTGTATGTGGCTCAGAAA | 159 |

| CGCCGTGGGTGTTCAAAATAAT | ||

| rpoB | GTAAGGCGCAGTTCGGTGG | 203 |

| TTTGAGCAGCACCTTGAACGA |

Two probes were designed per region of interest, one with the wild-type sequence according to the published sequences for M. tuberculosis H37Rv and CDC1551, the other containing the sSNP of interest (1). Each probe was 19 to 25 nucleotides long and contained a poly(T) tail of 20 bases (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Wild-type and mutant probe sequences

| Gene and nt position (sSNP)b | Wild-type probe

|

Mutant probe

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencea | Size (bp) | Sequencea | Size (bp) | |

| oxyR-37 (G-A) | CCACCGCGGCGAACGCGCGAAGCCCTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT | 35 | GCGGCGAACGCGCGAAACCCGTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT | 31 |

| katG-87 (C-A) | ACCCCGTCGAGGGCGGCGGTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT | 29 | ACCCAGTCGAGGGCGGCGGATTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT | 30 |

| rpoB-2646 (A-C) | CGGCCAGCTTGTCACCGTCGGTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT | 31 | CGGCCAGCTTGTCCCCGTCGGTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT | 31 |

| rpoB-3243 (A-G) | CTCCTGCAGGGTGTAGGCAGCTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT | 31 | TCCTGCAGGGTGTAGGCGGCATTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT | 31 |

Polymorphic sites are boldfaced.

In parentheses are wild-type-to-mutant base conversions.

Each oligonucleotide (20 μM containing 0.001% bromophenol blue), an ink dot (for membrane orientation), and a color detection control (2 μM of oxyR primer) were dotted onto a nylon membrane (see Fig. 1) and fixed by UV cross-linking. The membrane was washed twice in wash solution (0.5× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate]-0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]) for 5 min and allowed to air dry.

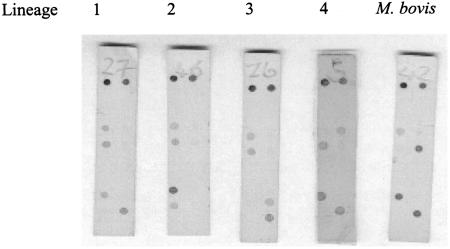

FIG. 1.

Hybridization patterns corresponding to the sSNP defining each lineage. Orientation of probes from left to right and top to bottom: ink spot, color development control, four blanks, wild-type oxyR-37, mutant oxyR-37, wild-type katG-87, mutant katG-87, four blanks, wild-type rpoB-2646, mutant rpoB-2646, wild-type rpoB-3243, and mutant rpoB-3243. Blanks were included to extend the length of the macroarray for ease of handling.

Twelve microliters of amplified oxyR-37 and rpoB-3243 from each sample were combined. katG-87 and rpoB-2646 amplified products were first diluted 1:10, and then 12 μl was added. The DNA mix was denatured at 100°C for 10 min. Hybridization and detection were performed as previously described (24) with the following modifications. Denatured DNA and 500 μl of hybridization solution (5× SSPE [1× SSPE is 0.18 M NaCl, 10 mM NaH2PO4, and 1 mM EDTA {pH 7.7}]-0.5% SDS) were incubated with a membrane for 1 h at 60°C. Membranes were washed twice in stringent wash buffer (0.3× SSPE-0.5% SDS) for 1 min at room temperature and then once in stringent wash buffer at 60°C for 10 min. The following washes were all carried out at room temperature. Membranes were washed twice in rinse buffer (0.1 M Tris, 0.1 M NaCl, pH 7.5) and then incubated for 1 min in 5 ml rinse buffer containing 0.5% blocking reagent before addition of streptavidin-alkaline phosphate (Roche, East Sussex, United Kingdom) and incubation for 30 min. Membranes were washed twice with rinse buffer (0.1 M Tris, 0.1 M NaCl, pH 7.5) for 1 min and then equilibrated in a second rinse buffer (0.1 M Tris, 0.1 M NaCl, pH 9.5) before incubation in a color development solution (75-mg/ml nitroblue tetrazolium [U.S. Biochemicals, Cleveland, Ohio] in 70% dimethylformamide and 50-mg/ml 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate [U.S. Biochemicals] in 100% dimethylformamide) for 1 h.

RESULTS

MIRU-VNTR analysis of panel 1.

A test population of 312 M. tuberculosis isolates classified by sSNP analysis into four M. tuberculosis lineages plus M. bovis (1) was typed using 15-locus MIRU-VNTR profiling. MIRU-VNTR profiles were obtained from 309/312 (99.0%) M. tuberculosis isolates (the remaining 3 were removed from further analysis) and 4/4 (100%) M. bovis isolates. These isolates were examined to determine whether any single MIRU-VNTR polymorphism or combination of polymorphisms was common to each lineage and could potentially be used to define each lineage.

Analysis of MIRU-VNTR profiles showed that the allelic diversity at certain loci was conserved while others varied considerably. No single MIRU-VNTR polymorphism was exclusive to a lineage. By using a combination of polymorphisms, each of the five main phylogenetic branches of the tree could be defined. For example, in lineage I the majority of isolates (95%) contained 3 copies of MIRU-39 and 4 copies of ETR-A, and all isolates contained 4 copies of ETR-C (Table 3). Taken together, 90% of the isolates in lineage I contained all three polymorphisms, i.e., they defined lineage I. The same analysis was performed on the other lineages.

TABLE 3.

MIRU-VNTR phylogenetic codes for each lineage based on panel 1

| Lineage (n)a | MIRU-VNTR codeb (no. of isolates with correct repeat no./total isolates [%]) | Combined MIRU-VNTRc

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Code | No. of isolates with correct combined repeat no./total isolates (%) | ||

| I (20) | 39-3 (19/20 [95]) | 39-3 | 18/20 (90) |

| A-4 (19/20 [95]) | A-4 | ||

| C-4 (20/20 [100]) | C-4 | ||

| II (168) | 16-1,2,3 (164/167 [98.2]) | 16-1,2,3 | 153/166 (92.7) |

| 39-2 (160/167 [95.8]) | 39-2 | ||

| B-1,2 (162/166 [97.6]) | B-1,2 | ||

| III (62) | 23-5 (61/62 [98.4]) | 23-5 | 61/62 (98.4) |

| C-2 (62/62 [100]) | C-2 | ||

| IV (62) | 24-2 (61/61 [100]) | 24-2 | 59/61 (96.7) |

| 26-2 (60/62 [98.8]) | 26-2 | ||

| M. bovis (4) | 10-2 (4/4 [100]) | 10-2 | 4/4 (100) |

| 40-2 (4/4 [100]) | 40-2 | ||

| C-5 (4/4 [100]) | C-5 | ||

Some loci would not amplify; therefore, two isolates from lineage II and one isolate from lineage IV were excluded from the analyses, leaving a total of 309 M. tuberculosis isolates in panel 1.

Each code consists of the MIRU (numbers) or ETR (letters) designation followed by a dash and the number of copies. For example, 16-1,2,3 indicates 1, 2, or 3 copies of MIRU-16; A-4 indicates 4 copies of ETR-A.

Combination of MIRU-VNTR producing the most unambiguous definition of each lineage. The number and percentage of isolates tested that were correctly identified using this combination are given.

Lineage III was highly conserved, with 98.4% of isolates containing the two polymorphisms defining their group, i.e., 5 copies of MIRU-23 and 2 copies of ETR-C. Lineage IV also displayed a high level of conservation, with 96.7% of isolates containing 2 copies each of MIRU-24 and MIRU-26. The code for lineage II was more variable; therefore, identifying a single defining allele at any locus was difficult. Instead, a combination of alleles at each locus was used—1, 2, or 3 copies of MIRU-16, 2 copies of MIRU-39, and 1 or 2 copies of ETR-B—which defined 92.7% of isolates. M. tuberculosis H37Rv, which belongs to lineage II, also displayed a lineage II code.

All M. bovis isolates contained the three polymorphisms defining their lineage; however, only four isolates were examined originally by Baker et al. (1). We confirmed that this code was robust by characterizing 45 additional M. bovis isolates with the macroarray and MIRU-VNTR (results below).

Macroarray analysis.

Based on the sSNP analysis described by Baker et al. (1), a macroarray was developed to identify the sSNPs that define lineages and was validated using 46 strains belonging to panel 1. The macroarray and original sSNP results were concordant, i.e., the macroarray correctly identified the lineage of each isolate based on the detection of probe-defined sSNPs. The hybridization patterns for each lineage are shown in Fig. 1. For example a lineage 1 isolate displays a positive hybridization signal at the wild-type oxyR-37, katG-87, and rpoB-2646 probes, while at rpoB-3243 a positive hybridization signal is observed for the mutant probe.

MIRU-VNTR analysis of panel 2.

In order to validate the MIRU-VNTR codes defined with the test population, panel 2 (205 isolates) was MIRU-VNTR typed and analyzed for sSNPs with the macroarray. Overall, there was 88.8% concordance between the lineages of all isolates defined by the macroarray and MIRU-VNTR. The M. bovis lineage was 88.9% concordant, demonstrating that in the majority of cases M. bovis can easily be differentiated from M. tuberculosis. Within the M. tuberculosis lineages alone, the level of concordance ranged from 81.3% to 100% (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Number of isolates in panel 2 belonging to each lineage according to the macroarray and concordance with MIRU-VNTR results

| Lineage defined by macroarray | No. of isolates | Defined MIRU-VNTR loci-repeat no.a | Comparison of macroarray with MIRU-VNTR

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concordanceb | No. (%) of discrepant results | |||

| I | 16 | 39-3, A-4, C-4 | 13/16 (81.3) | 3 (18.8) |

| II | 79 | 16-1,2,3, 39-2, B-1,2 | 68/79 (86.1) | 11 (13.9) |

| III | 38 | 23-5, C-2 | 38/38 (100) | 0 (0.0) |

| IV | 27 | 24-2, 26-2 | 23/27 (85.2) | 4 (14.8) |

| M. bovis | 45 | 10-2, 40-2, C-5 | 40/45 (88.9) | 5 (11.1) |

| Total | 205 | 182 (88.8) | 23 (11.2) | |

Combination of MIRU-VNTR (with repeat number at each locus) producing the most unambiguous definition of each lineage. Numbers stand for MIRU (e.g., 39-3 indicates 3 copies of MIRU-39); letters stand for ETR (e.g., A-4 indicates 4 copies of ETR-A).

Expressed as the number of isolates with concordant results/total number of isolates (percent).

Analysis of both panels by MIRU-VNTR.

Combining panels 1 and 2 gave 518 isolates (465 M. tuberculosis and 49 M. bovis isolates) analyzed by both MIRU-VNTR and sSNP (DNA sequencing or the macroarray). Overall, there was 90.9% concordance between lineage-defined MIRU-VNTR phylogenetic codes and sSNP-defined lineages. The percentage of definable isolates ranged from 86.1 to 99.0% for M. tuberculosis and was 89.8% for M. bovis (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Number of isolates belonging to each lineage according to sSNP analysis and concordance with MIRU-VNTR results for all M. tuberculosis and M. bovis isolates tested

| Lineage defined by sSNPs | Total no. of isolates testeda | Concordance with MIRU-VNTR results (%) |

|---|---|---|

| I | 36 | 31 (86.1) |

| II | 245 | 220 (89.8) |

| III | 100 | 99 (99.0) |

| IV | 88 | 77 (87.5) |

| M. bovis | 49 | 44 (89.8) |

| Total | 518 | 471 (90.9) |

Excludes three isolates from panel 1 that did not amplify.

Discrepant results.

Since sSNPs display neutral variation, they are unlikely to be under any selection pressures. The sSNPs discussed here are concordant with other genetic and phenotypic groupings (including genetic groups 1 to 3, M. tuberculosis-specific deletions, spoligotyping, and IS6110 families) (1), and therefore they are likely to be definitive. Any disagreement with the sSNP-defined lineages was considered discrepant. Overall, 47 (9.1%) discrepant results were observed, i.e., the MIRU-VNTR code did not match the lineage defined by sSNP analysis (Table 6). Of the M. tuberculosis isolates, 27/42 (64.3%) did not match any of the defined MIRU-VNTR codes but had a MIRU-VNTR code very similar to that for one of the four lineages, and in each case this matched the lineage defined by sSNP analysis. For example, five isolates with lineage II discrepancy b had a VNTR code similar to that of lineage II. These isolates differed at MIRU-39, possessing 1 copy instead of 2 copies. Three isolates with lineage II discrepancy g contained 5 copies of MIRU-16 and 3 copies of ETR-B as opposed to the predicted profile, 2 or 3 copies of MIRU-16 and 1 or 2 copies of ETR-B. In all lineages, the allelic diversity at the discrepant loci displayed a stepwise trend. For example, isolates with discrepancies b to e in lineage II contained either 1 or 3 copies of MIRU-39 instead of 2 copies, and isolates with discrepancy g or i contained 3 copies of ETR-B instead of 1 or 2 copies. These discrepancies support the presence of sublineages within lineage II.

TABLE 6.

Discrepancies observed in each lineage from a total population of 518 isolates

| Lineage | Defined MIRU-VNTR loci-repeat no.a | Discrepancy | Discrepant MIRU-VNTR code(s)b | No. of times observed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 39-3, A-4, C-4 | a | 39-2, A-3, C-4 + code for lineage II | 1 |

| b | 39-2, A-4, C-4 + code for lineage II | 2 | ||

| c | 39-3, A-3, C-4 | 1 | ||

| e | 39-4, A-4, C-4 | 1 | ||

| II | 16-1,2,3, 39-2, B-1,2 | a | Codes for lineages II and III present | 3 |

| b | 16-3, 39-1, B-2 | 5 | ||

| c | 16-3, 39-1, B-1 | 2 | ||

| d | 16-1, 39-3, B-1 | 1 | ||

| e | 16-3, 39-3, B-2 | 4 | ||

| f | 16-4, 39-2, B-2 | 4 | ||

| g | 16-5, 39-2, B-3 | 3 | ||

| h | 16-1, 39-2, B-3 | 2 | ||

| i | 16-3, 39-2, B-3 | 1 | ||

| III | 23-5, C-2 | a | 23-3, C-2 | 1 |

| IV | 24-2, 26-2 | a | Codes for lineages I and IV present | 6 |

| b | Codes for lineages II and IV present | 2 | ||

| c | Codes for lineages III and IV present | 1 | ||

| d | 24-2, 26-1 | 2 | ||

| M. bovis | 10-2, 40-2, C-5 | a | 10-2, 40-2, C-2 | 1 |

| b | 10-2, 40-2, C-3 | 1 | ||

| c | 10-2, 40-2, C-4 | 1 | ||

| d | 10-6, 40-2, C-4 | 1 | ||

| e | 10-2, 40-3, C-5 | 1 |

Numbers stand for MIRU (e.g., 16-1,2,3 indicates that there are 1, 2, or 3 copies of MIRU-16); letters stand for ETR (e.g., A-4 indicates that there are 4 copies of ETR-A).

Discrepant loci are boldfaced.

Twelve M. tuberculosis isolates had MIRU-VNTR codes for two lineages. Three isolates defined as lineage II by sSNP analysis had the MIRU-VNTR codes for both lineages II and III, and nine isolates defined as lineage IV had the code for this lineage plus another M. tuberculosis lineage code. The phylogenetic code for lineage IV was exclusive and was not observed in any other lineage; therefore, it seems that any discrepant isolate containing the MIRU-VNTR code for lineage IV should be designated a lineage IV strain. However, the MIRU-VNTR code for lineage II was not exclusive, making it difficult to determine to which lineage these isolates belonged. Only 3/245 (1.2%) isolates in lineage II had two codes; therefore, the chances of this occurring are probably low. Interestingly, if the code for lineage II is modified by only counting 2 copies of ETR-B instead of 1 and 2 copies, then the code becomes highly conserved and is not observed in any other lineage. However, the increase in specificity is outweighed by the loss in sensitivity, reducing the proportion of isolates defined from 92.7% to 76.3%.

The remaining three discrepant strains were defined as lineage I according to sSNP analysis, but all had the lineage II code and a partial code for lineage I. All three had a Beijing spoligotype (spacers 1 to 34 absent, spacers 35 to 43 present) and may represent evolutionary intermediates.

Of the discrepant M. bovis isolates, all five had different codes. Again, a stepwise trend was seen among the discrepant isolates. For example, 2, 3, 4, and 5 copies of ETR-C were observed.

Indeterminate isolates.

Four isolates not assigned a lineage in the Baker et al. panel (1) because of incomplete MLST data were analyzed by MIRU-VNTR to determine whether they could be classified using these codes. Three isolates had the MIRU-VNTR code for lineage II and none of the other codes. The remaining isolate had a code similar to that for lineage I except that it had 5 copies of ETR-A instead of 4. sSNP macroarray analysis confirmed that three of the isolates were indeed from lineage II and the remaining isolate was from lineage I.

MIRU-VNTR discrimination.

Once a population of strains has been assigned to a lineage, it would be useful for epidemiological studies to be able to subdivide lineages into epidemiologically linked and unique isolates. The discriminatory power of each MIRU-VNTR locus was examined, and a specific set of MIRU-VNTR capable of subdividing each lineage was determined (Table 7). Because the MIRU-VNTR used to define each lineage were conserved, they would not be useful for epidemiological studies, where the ability to detect maximum diversity is required. A combination of six loci (MIRU-16, -26, -27, -31, and -20 and ETR-A), when applied to lineage I isolates, was able to generate the same degree of discrimination as the 15-locus MIRU-VNTR overall. The number of MIRU-VNTR loci could not be reduced for lineage II without reducing the discrimination. Nine loci in lineage III (MIRU-10, -16, -20, -26, -27, -31, -39, and -40 and ETR-B) and eight in lineage IV (MIRU-4, -10, -31, -39, -40, and -23, ETR-A, and ETR-B) differentiated all isolates. The greatest discrimination within the M. bovis lineage was achieved with eight loci: MIRU-23, -24, -26, and -27, ETR-A, ETR-B, and a combination of two MIRU-VNTR from MIRU-4, -31, and -39. However, if a lower level of discrimination is acceptable, then an even smaller number of MIRU-VNTR can be used, which may be of value for laboratories with resource constraints. For example, by allowing 4 or fewer discrepancies per lineage (i.e., those isolates that are clustered by using a smaller panel of MIRU-VNTR compared to the clustering seen with all 15 MIRU-VNTR), 4, 12, 7, 7, or 6 MIRU-VNTR would be sufficient to produce the same level of intralineage discrimination as the whole panel when applied to lineage I, II, III, or IV or M. bovis, respectively (Table 7).

TABLE 7.

MIRU-VNTR loci used to subdivide each lineage into true clustered and true unique isolates

| Lineage (n) | No. of clusters | No. of clustered isolates | No. of unique isolates | MIRU-VNTR (no. of discrepancies)a | Additional MIRU-VNTR for total discrimination (no. of discrepancies)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (36) | 6 | 27 | 9 | 16, 26, 27, 31 (4) | A (1) |

| A, 20 (0) | |||||

| II (245) | 30 | 120 | 125 | 4, 10, 16, 20, 23, 26, 27, 31, 39, 40, A, C (4) | B (2) |

| B, 2 (1) | |||||

| B, 2, 24 (0) | |||||

| III (100) | 15 | 63 | 37 | 10, 16, 26, 31, 39, 40, B (2) | 20 (1) |

| 20, 27 (0) | |||||

| IV (88) | 7 | 19 | 69 | 4, 10, 31, 39, A, B, 40 (2) | 23 (0) |

| M. bovis (49) | 5 | 10 | 39 | 23, 24, 26, 27, A, B (3) | Combination of two MIRU from 4, 31, and 39 (0) |

Numbers indicate MIRU (e.g., 16 stands for MIRU-16); letters indicate ETR (e.g., A stands for ETR-A). Isolates could initially be screened with a smaller panel of MIRU-VNTR in a resource-constrained laboratory wishing to produce a high level of intralineage discrimination for epidemiological purposes at a lower cost. This column shows the maximum number of MIRU-VNTR loci required to produce four or fewer discrepancies (i.e., isolates which are clustered by using a smaller panel of MIRU-VNTRs compared to clustering with all 15 MIRU-VNTR).

Additional MIRU-VNTR loci that would need to be added to the smaller panel to give the same level of intralineage discrimination of clustered isolates as the whole panel.

DISCUSSION

The identification of key phylogenetic markers within populations of isolates is important in order to aid in our understanding of M. tuberculosis complex evolution and pathogenesis. A series of such markers in M. tuberculosis and M. bovis have been described previously by Baker et al. (1), who defined five distinct lineages. MIRU-VNTR is a rapid, high-throughput typing tool that provides useful epidemiological markers for use in tuberculosis outbreaks and control programs. If the numeric codes by which MIRU-VNTR types are expressed can also define phylogenetic lineages, very large populations of M. tuberculosis complex isolates can be used in M. tuberculosis evolution studies, since this typing system is beginning to be used routinely in some centers both in the United Kingdom and globally.

In this study MIRU-VNTR was successfully applied to a test population to determine phylogenetic codes capable of defining each of the lineages described previously. To validate these MIRU-VNTR codes, an additional panel was analyzed. This panel was characterized with a portable sSNP-based macroarray. Developing a macroarray to identify known sSNPs in a population allowed rapid identification to species level and identification of key lineages. The macroarray eliminated the need for time-consuming, more-costly sequencing and so proved useful as a preliminary screening tool for M. tuberculosis and M. bovis populations.

Overall, the MIRU-VNTR phylogenetic codes were able to define 90.9% of sSNP-characterized M. tuberculosis and M. bovis isolates by using a combination of just 10 of the 15 loci examined.

Lineage I accommodates the Beijing family strains. In this study, 86.1% of the Beijing isolates were defined using the MIRU-VNTR lineage I code. Although MIRU-VNTR codes are not as definitive as spoligotyping, dnaA-dnaN (7, 12, 18), and sSNP analysis, the data shown here demonstrate that it is a good additional screening marker for Beijing-type strains. Ferdinand et al. (11) genotyped spoligotype-defined families using the 12-MIRU system. They found that all Beijing isolates could be characterized using a maximum of six MIRU; since the focus was to characterize all isolates, the loci and repeat numbers used were not the same for all Beijing isolates. A single code for the identification of Beijing isolates may be more useful before, or in parallel with, discrimination between these isolates.

Lineage III contained the Central Asian family (CAS)/Delhi family of strains (2, 12). The MIRU-VNTR code for this family, 5 copies of MIRU-23 and 2 copies of ETR-C, defined 99% of the isolates, making the differentiation of CAS/Delhi strains within a population simple and specific.

Locus MIRU-24 has previously been used to classify M. tuberculosis strains into two groups: those containing 1 copy and those containing 2 or 3 copies (11). Our MIRU-VNTR data are in agreement with those of Ferdinand et al. (11), who found that 97.8% of East African-Indian (EAI) strains contained 2 copies of MIRU-24. The EAI strains in our study were found in lineage IV. However, other strains, including M. bovis strains, contained 2 copies of MIRU-24; therefore, this locus could not be used to define lineage IV alone. The addition of MIRU-26 resulted in this code becoming exclusive, thus providing a simple code to define this family.

An important observation was that the M. bovis phylogenetic code was unique and was not observed for any M. tuberculosis isolates. Therefore, this phylogenetic code is an excellent marker for differentiating between these two species.

The stepwise trend seen among discrepant isolates suggests that evolution is bidirectional in that the number of repeat copies either increases or decreases over time. Indeed, certain loci show more allelic diversity than others, which may be due to different selection pressures acting at different loci. The molecular clocks of some loci may be faster than others, and certain loci may tolerate more polymorphisms than others. The exact function of MIRU is not known, and it is not known whether individual MIRU have different functions. Their high variability may be a way for the bacteria to adapt to a new environment. Changes in the copy number of tandem repeats may affect gene regulation (29) and have been shown to affect the expression of genes involved in adaptive responses (22). In Haemophilus influenzae, variability of repeat number has an effect on virulence (22, 31). These findings suggest that a similar phenomenon could be occurring in the MIRU-VNTR of M. tuberculosis complex.

MIRU-VNTR can simultaneously define phylogeny and differentiate strains, as demonstrated in this study. A lineage-specific panel of MIRU-VNTR was used subsequently to subdivide each lineage into clustered and unique strains, thus eliminating the need to analyze all 15 MIRU for every isolate. The advantage of using a smaller panel of MIRU-VNTR is a reduction in the cost of the analysis. In molecular epidemiological studies, total discrimination would normally be required; therefore, isolates could be screened initially with a small MIRU-VNTR panel, followed by analysis of clustered isolates with additional MIRU-VNTR for total discrimination (with additional typing techniques as required).

MIRU-VNTR can characterize a population of M. tuberculosis and M. bovis isolates for phylogenetic/evolutionary purposes. It is also suggested that MIRU-VNTR is able to provide information on sublineages and molecular clocks. MIRU-VNTR analysis is a high-throughput, reproducible method, producing digital results that are readily portable between laboratories, and so is suited to phylogenetic studies as well as having a high discriminatory value for molecular epidemiological investigations. Conversely, although genotyping by indexing genetically neutral variation provides a robust phylogeny for M. tuberculosis, its value is limited for definitive epidemiological typing. This study demonstrated that MIRU-VNTR profiling can be used for rapid classification of M. tuberculosis and M. bovis isolates. Future studies should investigate the potential for extending the use of MIRU-VNTR to identify the other members of the M. tuberculosis complex: Mycobacterium africanum, Mycobacterium microti, and Mycobacterium canetti.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded in part by the United Kingdom Department of Health, Department for International Development (CNTR 00 00134), and the Health Protection Agency.

We thank all our colleagues at the MRU for their help and support. We particularly thank Krishna Gopaul for invaluable advice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baker, L., T. Brown, M. C. Maiden, and F. Drobniewski. 2004. Silent nucleotide polymorphisms and a phylogeny for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:1568-1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhanu, N. V., D. van Soolingen, J. D. van Embden, L. Dar, R. M. Pandey, and P. Seth. 2002. Predominance of a novel Mycobacterium tuberculosis genotype in the Delhi region of India. Tuberculosis (Edinburgh) 82:105-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brosch, R., S. V. Gordon, M. Marmiesse, P. Brodin, C. Buchrieser, K. Eiglmeier, T. Garnier, C. Gutierrez, G. Hewinson, K. Kremer, L. M. Parsons, A. S. Pym, S. Samper, D. van Soolingen, and S. T. Cole. 2002. A new evolutionary scenario for the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:3684-3689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cowan, L. S., L. Mosher, L. Diem, J. P. Massey, and J. T. Crawford. 2002. Variable-number tandem repeat typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates with low copy numbers of IS6110 by using mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1592-1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dale, J. W., H. Al Ghusein, S. Al Hashmi, P. Butcher, A. L. Dickens, F. Drobniewski, K. J. Forbes, S. H. Gillespie, D. Lamprecht, T. D. McHugh, R. Pitman, N. Rastogi, A. T. Smith, C. Sola, and H. Yesilkaya. 2003. Evolutionary relationships among strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with few copies of IS6110. J. Bacteriol. 185:2555-2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dingle, K. E., F. M. Colles, D. R. Wareing, R. Ure, A. J. Fox, F. E. Bolton, H. J. Bootsma, R. J. Willems, R. Urwin, and M. C. Maiden. 2001. Multilocus sequence typing system for Campylobacter jejuni. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:14-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drobniewski, F., Y. Balabanova, M. Ruddy, L. Weldon, K. Jeltkova, T. Brown, N. Malomanova, E. Elizarova, A. Melentyey, E. Mutovkin, S. Zhakharova, and I. Fedorin. 2002. Rifampin- and multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Russian civilians and prison inmates: dominance of the Beijing strain family. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:1320-1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dye, C., G. P. Garnett, K. Sleeman, and B. G. Williams. 1998. Prospects for worldwide tuberculosis control under the WHO DOTS strategy. Directly observed short-course therapy. Lancet 352:1886-1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Enright, M. C., and B. G. Spratt. 1998. A multilocus sequence typing scheme for Streptococcus pneumoniae: identification of clones associated with serious invasive disease. Microbiology 144:3049-3060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang, Z., N. Morrison, B. Watt, C. Doig, and K. J. Forbes. 1998. IS6110 transposition and evolutionary scenario of the direct repeat locus in a group of closely related Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains. J. Bacteriol. 180:2102-2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferdinand, S., G. Valetudie, C. Sola, and N. Rastogi. 2004. Data mining of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex genotyping results using mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units validates the clonal structure of spoligotyping-defined families. Res. Microbiol. 155:647-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Filliol, I., J. R. Driscoll, D. van Soolingen, B. N. Kreiswirth, K. Kremer, G. Valetudie, D. D. Anh, R. Barlow, D. Banerjee, P. J. Bifani, K. Brudey, A. Cataldi, R. C. Cooksey, D. V. Cousins, J. W. Dale, O. A. Dellagostin, F. Drobniewski, G. Engelmann, S. Ferdinand, D. Gascoyne-Binzi, M. Gordon, M. C. Gutierrez, W. H. Haas, H. Heersma, G. Kallenius, E. Kassa-Kelembho, T. Koivula, H. M. Ly, A. Makristathis, C. Mammina, G. Martin, P. Mostrom, I. Mokrousov, V. Narbonne, O. Narvskaya, A. Nastasi, S. N. Niobe-Eyangoh, J. W. Pape, V. Rasolofo-Razanamparany, M. Ridell, M. L. Rossetti, F. Stauffer, P. N. Suffys, H. Takiff, J. Texier-Maugein, V. Vincent, J. H. de Waard, C. Sola, and N. Rastogi. 2002. Global distribution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis spoligotypes. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:1347-1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frothingham, R., and W. A. Meeker-O'Connell. 1998. Genetic diversity in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex based on variable numbers of tandem DNA repeats. Microbiology 144:1189-1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibson, A. L., G. Hewinson, T. Goodchild, B. Watt, A. Story, J. Inwald, and F. A. Drobniewski. 2004. Molecular epidemiology of disease due to Mycobacterium bovis in humans in the United Kingdom. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:431-434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gutacker, M. M., J. C. Smoot, C. A. Migliaccio, S. M. Ricklefs, S. Hua, D. V. Cousins, E. A. Graviss, E. Shashkina, B. N. Kreiswirth, and J. M. Musser. 2002. Genome-wide analysis of synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex organisms: resolution of genetic relationships among closely related microbial strains. Genetics 162:1533-1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hawkey, P. M., E. G. Smith, J. T. Evans, P. Monk, G. Bryan, H. H. Mohamed, M. Bardhan, and R. N. Pugh. 2003. Mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis compared to IS6110-based restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis for investigation of apparently clustered cases of tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3514-3520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kam, K. M., C. W. Yip, L. W. Tse, K. L. Wong, T. K. Lam, K. Kremer, B. K. Au, and D. van Soolingen. 2005. Utility of mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit typing for differentiating multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates of the Beijing family. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:306-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurepina, N. E., S. Sreevatsan, B. B. Plikaytis, P. J. Bifani, N. D. Connell, R. J. Donnelly, D. van Soolingen, J. M. Musser, and B. N. Kreiswirth. 1998. Characterization of the phylogenetic distribution and chromosomal insertion sites of five IS6110 elements in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: non-random integration in the dnaA-dnaN region. Tuber. Lung Dis. 79:31-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwara, A., R. Schiro, L. S. Cowan, N. E. Hyslop, M. F. Wiser, H. S. Roahen, P. Kissinger, L. Diem, and J. T. Crawford. 2003. Evaluation of the epidemiologic utility of secondary typing methods for differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:2683-2685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maiden, M. C., J. A. Bygraves, E. Feil, G. Morelli, J. E. Russell, R. Urwin, Q. Zhang, J. Zhou, K. Zurth, D. A. Caugant, I. M. Feavers, M. Achtman, and B. G. Spratt. 1998. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:3140-3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mokrousov, I., O. Narvskaya, E. Limeschenko, A. Vyazovaya, T. Otten, and B. Vyshnevskiy. 2004. Analysis of the allelic diversity of the mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units in Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains of the Beijing family: practical implications and evolutionary considerations. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:2438-2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moxon, E. R., P. B. Rainey, M. A. Nowak, and R. E. Lenski. 1994. Adaptive evolution of highly mutable loci in pathogenic bacteria. Curr. Biol. 4:24-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Musser, J. M., A. Amin, and S. Ramaswamy. 2000. Negligible genetic diversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis host immune system protein targets: evidence of limited selective pressure. Genetics 155:7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nikolayevsky, V., T. Brown, Y. Balabanova, M. Ruddy, I. Fedorin, and F. Drobniewski. 2004. Detection of mutations associated with isoniazid and rifampin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Samara Region, Russian Federation. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:4498-4502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raviglione, M. C., D. E. Snider, Jr., and A. Kochi. 1995. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis. Morbidity and mortality of a worldwide epidemic. JAMA 273:220-226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roring, S., A. N. Scott, H. R. Glyn, S. D. Neill, and R. A. Skuce. 2004. Evaluation of variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) loci in molecular typing of Mycobacterium bovis isolates from Ireland. Vet. Microbiol. 101:65-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sola, C., I. Filliol, E. Legrand, I. Mokrousov, and N. Rastogi. 2001. Mycobacterium tuberculosis phylogeny reconstruction based on combined numerical analysis with IS1081, IS6110, VNTR, and DR-based spoligotyping suggests the existence of two new phylogeographical clades. J. Mol. Evol. 53:680-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sreevatsan, S., X. Pan, K. E. Stockbauer, N. D. Connell, B. N. Kreiswirth, T. S. Whittam, and J. M. Musser. 1997. Restricted structural gene polymorphism in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex indicates evolutionarily recent global dissemination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:9869-9874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Supply, P., J. Magdalena, S. Himpens, and C. Locht. 1997. Identification of novel intergenic repetitive units in a mycobacterial two-component system operon. Mol. Microbiol. 26:991-1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Supply, P., S. Lesjean, E. Savine, K. Kremer, D. van Soolingen, and C. Locht. 2001. Automated high-throughput genotyping for study of global epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis based on mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3563-3571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Belkum, A., S. Scherer, W. van Leeuwen, D. Willemse, L. van Alphen, and H. Verbrugh. 1997. Variable number of tandem repeats in clinical strains of Haemophilus influenzae. Infect. Immun. 65:5017-5027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]