Abstract

Strains of Staphylococcus aureus obtained from bovine (n = 117) and caprine (n = 114) bulk milk were characterized and compared with S. aureus strains from raw-milk products (n = 27), bovine mastitis specimens (n = 9), and human blood cultures (n = 39). All isolates were typed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). In addition, subsets of isolates were characterized using multilocus sequence typing (MLST), multiplex PCR (m-PCR) for genes encoding nine of the staphylococcal enterotoxins (SE), and the cloverleaf method for penicillin resistance. A variety of genotypes were observed, and greater genetic diversity was found among bovine than caprine bulk milk isolates. Certain genotypes, with a wide geographic distribution, were common to bovine and caprine bulk milk and may represent ruminant-specialized S. aureus. Isolates with genotypes indistinguishable from those of strains from ruminant mastitis were frequently found in bulk milk, and strains with genotypes indistinguishable from those from bulk milk were observed in raw-milk products. This indicates that S. aureus from infected udders may contaminate bulk milk and, subsequently, raw-milk products. Human blood culture isolates were diverse and differed from isolates from other sources. Genotyping by PFGE, MLST, and m-PCR for SE genes largely corresponded. In general, isolates with indistinguishable PFGE banding patterns had the same SE gene profile and isolates with identical SE gene profiles were placed together in PFGE clusters. Phylogenetic analyses agreed with the division of MLST sequence types into clonal complexes, and isolates within the same clonal complex had the same SE gene profile. Furthermore, isolates within PFGE clusters generally belonged to the same clonal complex.

Staphylococcus aureus is a commensal organism and a versatile pathogen in animals and humans. It is the cause of superficial and deep infections and, by virtue of its exotoxins, of a variety of toxemic syndromes. Some strains produce staphylococcal enterotoxins (SEs) that can cause food poisoning if food containing preformed SE is ingested. Symptoms of staphylococcal food poisoning (SFP) have a rapid onset (2 to 6 h) and may include vomiting, stomach pain, and diarrhea (18). To date, 18 SEs have been described and designated SEA to SEE, SEG to SER, and SEU (10, 19, 24, 27, 33-36). Some of them, however, lack the ability to cause emesis or have not been tested for emetic effect, and these are more accurately termed staphylococcal enterotoxin-like proteins (28).

Milk and milk products have frequently been implicated in SFP, and contaminated raw milk is often involved (2, 8). S. aureus mastitis is a serious problem in dairy production, and infected animals may contaminate bulk milk. Human handlers, milking equipment, the environment, and the udder and teat skin of dairy animals are other possible sources of bulk milk contamination (16, 44). S. aureus was recently isolated from 75% and 93% of Norwegian bovine and caprine bulk milk samples, respectively, and approximately 55% of the isolates tested contained SE genes (20). From a food safety perspective, this is a concern because enterotoxigenic S. aureus may pose a risk of SFP from milk products. Efficient chilling of bulk milk until pasteurization, followed by efforts to prevent recontamination, minimizes the risk of SFP from milk products, but when raw milk is used for production, contaminated bulk milk may be hazardous, particularly in situations where S. aureus contamination is significant or when starter cultures or other conditions fail.

Staphylococcus aureus is known to show host specialization, and certain phenotypic and genotypic traits, such as production of beta-hemolysin, SE gene profiles, and antibiotic resistance may differ between populations of S. aureus from different species (4, 9, 15). Multiple studies have characterized the genotypic diversity of S. aureus from cases of bovine mastitis (13,21, 38), but few have investigated S. aureus from bulk milk(5,39). Knowledge about the genotypic variation among S.aureus isolates from bulk milk could aid in the implementation of strategies to decrease S. aureus levels in bulk milk and could be useful in future investigations of SFP from raw-milk products, since the presence of certain genotypes in the product might point to a possible source of contamination.

Genotyping by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) has proved useful in epidemiological investigations of S. aureus nosocomial infections (42) and has also been used to determine the source of S. aureus in outbreaks of SFP (6, 30). In PFGE, electrophoretic banding patterns of uncharacterized genomic restriction fragments are used as a basis for comparing bacterial isolates, but the degree of genetic relatedness between epidemiologically unrelated isolates may be difficult to interpret on the basis of this technique (43). For comparison of epidemiologically unrelated isolates, genotyping by multilocus sequence typing (MLST), which is based on DNA sequencing of seven S. aureus housekeeping genes, may be more useful. However, since housekeeping genes are relatively stable by nature, and changes in these genes accumulate slowly over time, MLST is usually less discriminatory than PFGE (37). It is therefore advantageous to employ both techniques when characterizing bacterial populations.

The primary aim of the present work was to investigate the genotypic variation among isolates of S. aureus from Norwegian bovine and caprine bulk milk. A further objective was to investigate whether S. aureus genotypes similar to those of prevalent ruminant mastitis clones in Norway were also frequently found in bulk milk, and whether S. aureus genotypes similar to those in bulk milk were found in raw-milk products. A selection of S. aureus isolates from human blood cultures was included in the study for comparative purposes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Staphylococcus aureus isolates.

Altogether 306 S. aureus isolates from bovine bulk milk (n = 117), caprine bulk milk (n = 114), raw-milk products (n = 27), cases of ruminant mastitis (n = 9), and human blood cultures (n = 39), were included. All were collected and identified as S. aureus in other studies (20, 25, 26, 31).

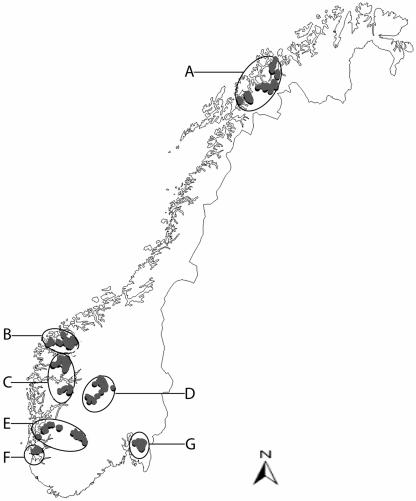

Bulk milk isolates were randomly selected from isolates obtained previously in a study where bovine and caprine bulk milk, from ca. 1% and 34% of the Norwegian bovine and caprine dairy farms, respectively, was analyzed for S.aureus (20). The farms were located in seven regions of Norway which largely corresponded to dairy districts (Fig. 1.). Bovine bulk milk isolates were collected from regions A, C, D, F, and G, while caprine bulk milk isolates were collected from regions A, B, C, D, and E.

FIG. 1.

Map of Norway showing regions (A to G) from which Staphylococcus aureus isolates from bovine (n = 117) and caprine (n = 114) bulk milk were collected. Bovine bulk milk isolates were collected from regions A (n = 25), C (n = 26), D (n = 26), F (n = 20), and G (n = 20), and caprine bulk milk isolates were collected from regions A (n = 25), B (n = 20), C (n = 25), D (n = 24), and E (n = 20).

Raw-milk product isolates were selected from isolates collected in the same study as the bulk milk isolates (20), which included product samples from up to 50% of Norwegian raw-milk product manufacturers. The 27 isolates were obtained from different samples and from 18 different producers. Products were made from bovine milk (n = 16) (butter [n = 1], semihard cheese [n = 8], soft/fresh cheese [n = 3], and soured cream [n = 4]) and from caprine milk (n = 9)(soft/fresh cheese [n = 1] and semihard cheese [n = 8]). In addition, two isolates were collected from two semihard cheeses made from reindeer milk. Samples were collected from regions C, D, and E. Two isolates were obtained from samples collected in close proximity to regions F and G.

Nine S. aureus isolates obtained from cases of clinical mastitis in Norwegian cows (n = 5), goats (n = 2), and sheep (n = 2) were included. These had been tested by PFGE previously and represented different PFGE banding patterns commonly observed for S. aureus isolates from cases of ruminant mastitis in Norway (31).

Thirty-nine S. aureus isolates from human blood cultures were also included; these were collected in six Norwegian hospitals between 1991 and 1999 (25, 26) (courtesy of Truls M. Leegaard, Rikshospitalet, Oslo, Norway). Two of the hospitals corresponded to regions A and B. The remaining hospitals did not correspond to the presently defined geographic regions.

PFGE.

All 306 S. aureus isolates were genotyped by PFGE. Preparation of buffers, macrorestriction of chromosomal DNA, and PFGE were performed according to Kaufmann (22). Briefly, bacterial suspensions were mixed with 2% low-melting-point agarose (BioProducts, Rockland, Maine), dispersed into molds, and set at 4°C. Plugs were transferred to 3 ml gram-positive lysis buffer with 30 U/ml lysostaphin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, Mo.) and 500 μg/ml lysozyme (Sigma-Aldrich) and were incubated for 5 h at 37°C. Plugs were subsequently incubated overnight at 56°C in 3 ml gram-negative lysis buffer with 60 μg/ml proteinase K (Sigma-Aldrich) and washed three times in Tris-EDTA buffer.

For DNA restriction, plugs were digested with SmaI (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Digested plugs were loaded into a 1.2% agarose gel (certified molecular biology agarose; Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) with 25 wells. On every gel, three lanes included molecular weight markers (Lambda ladder; Bio-Rad) and two lanes included internal-control strains (sk2a and sg37a). Electrophoresis was performed in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer for 30 h at 12°C and 6 V/cm, with initial and final pulse times of 1and 80 s, respectively. Gels were stained in ethidium bromide, destained in distilled water, and visualized and captured in UV light (Syngene, Cambridge, United Kingdom).

PFGE banding patterns were identified by a combination of visual inspection and computer analysis (BioNumerics, v. 4.00; Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium). Isolates with indistinguishable banding patterns were assigned to the same pulsotype (PT) and designated by capital letters and Arabic numerals.

Cluster analyses were performed in BioNumerics. Pairwise similarity coefficients were calculated using the Dice formula, and dendrograms were created using the unweighted-pair group method using geometric averages (UPGMA). For the data set of 306 restriction profiles, the most appropriate settings, as determined by the software, were 0.87% position tolerance and 0.68% optimization. With these settings, the internal-control isolates clustered with >97% similarity. The cluster cutoff was set at 80% similarity.

Within clusters with >1 isolate, pairwise comparisons of isolates were studied using the similarity matrix of the dendrogram. Comparisons where two isolates within a cluster differed by >6 bands were recorded.

MLST.

One hundred and one of the S. aureus isolates from bovine (n = 50) and caprine (n = 39) bulk milk and from raw-milk products (n = 12) were analyzed by MLST. The isolates were randomly selected from the raw-milk product isolates and from bulk milk isolates from regions A, C, D, and F. Thirteen isolates each from bovine and caprine bulk milk were selected from each of regions A, C, and D, and 11 isolates from bovine bulk milk were selected from region F.

MLST was carried out by PCR amplification of ∼450-bp fragments of the seven housekeeping genes: arcC, aroeE, glpF, gmk, pta, tpi, and yqiL. Information on the loci, DNA isolation, primer sequences, and PCR conditions is available at the MLST database (http://www.mlst.net).

The PCR products were visualized on agarose gels and purified using a PCR Product presequencing kit (USB, Ohio). Sequencing was performed both in the forward and in the reverse direction using the same primers as those for PCR. Sequencing was performed using BigDye terminator reaction mix v 2.0 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The elongation products were loaded into a 5% Long-Ranger gel (Cambrex, Rockland, ME), and the DNA sequences were read automatically with an ABI Prism 377 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems). The results were analyzed using the AutoAssembler TM software v. 2.1 program (Applied Biosystems). In cases of uncertainty or mismatch at a specific base between the two sequences, new sequencing reactions were performed and analyzed.

The sequences for each locus were compared to the allele sequences in the MLST database. Alleles without a match in the database were submitted for registration. Isolates were defined by their alleles at the seven loci (allelic profile), and each allelic profile was assigned to a sequence type (ST), either as already defined in the database or as designated by the website curator for new registrations.

The eBURST program (http://www.mlst.net) was used to divide the STs into clonal complexes (CC) and to identify the ST that was the most likely founder within each clonal complex. A clonal complex is a group of STs where every ST shares six of seven identical alleles with at least one other ST in the group. Because ancestral STs initially diversify to produce variants that differ at only one of the seven loci, a predicted ancestor or founder ST can be proposed for a clonal complex on the basis of the fact that it differs at a single locus from the highest number of other STs in the clonal complex.

Two analyses were performed using eBURST with default settings. One was performed on a data set including the STs presently observed. In order to see how the STs presently observed compared to STs observed by others, another eBURST analysis was performed on the entire S. aureus database, which included 366 registered STs (April 2005).

Phylogenetic analyses of MLST sequences.

The sequences of all seven loci of each ST were concatenated to produce an in-frame sequence of 3,198 bp. Phylogenetic trees were generated in PAUP*, version 4.0b10 (Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA), using the maximum-parsimony method employing a heuristic search (1,000 random replicates). Trees were generated for each of the seven loci of the alleles of the presently observed STs and for the concatenated sequences of the 22 observed STs. A strict consensus tree, showing branches agreed on by the most parsimonious trees, was also created. In order to evaluate the support for the observed branching topologies for maximum parsimony, bootstrap analysis (12) was performed. Bootstrapping was done with a heuristic algorithm and 1,000 random additions of sequences per bootstrap replicate.

m-PCR for enterotoxin genes.

Forty S. aureus isolates from bovine (n = 21) and caprine (n = 19) bulk milk were tested by a multiplex-PCR (m-PCR) method for detection of fragments of the sea to see and seg to sej genes and of the gene encoding toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 (TSST-1) (tst) (29). The method includes primers for 16S rRNA for control of DNA isolation, as well as four S. aureus reference strains (FRI 913, 3169, R5460, R5010) as positive controls that contain all the genes detected by the m-PCR. MilliQ water was used as a negative control. The remaining S. aureus isolates from bovine and caprine bulk milk and from raw-milk products had already been tested by the same m-PCR (20).

Cloverleaf method.

The 258 S. aureus isolates from bulk milk and from raw-milk products and the 9 mastitis isolates were tested for inactivation of penicillin (β-lactamase activity) by the cloverleaf method. Testing was performed as described by Bergan et al. (3). Briefly, a penicillin-sensitive S. aureus indicator strain (ATCC 25923) was suspended in physiological saline water and used to flood Mueller-Hinton agar plates (Difco); the plates were air dried; and four test isolates were streaked, in the shape of a cross, on each plate. A Penicillin Low tablet (5 μg; A/S Rosco, Taastrup, Denmark) was placed in the center of the plate. Plates were incubated aerobically for 24 h at 37°C. Growth of the indicator strain along the whole length of the test strain indicated a positive reaction.

RESULTS

PFGE restriction profiles.

Altogether 114 PTs were recognized among the 306 S. aureus isolates typed by PFGE. Between 1 and 28 isolates were assigned to each pulsotype. Isolates from bovine bulk milk (n = 117), caprine bulk milk (n = 114), raw-milk products (n = 27), and human blood cultures (n= 39) were divided into 41, 37, 12, and 36 pulsotypes, respectively. The present PFGE analyses also confirmed that the ruminant mastitis (n = 9) isolates belonged to nine different pulsotypes.

Pulsotypes to which >1 isolate was assigned are listed in Table 1. Out of the 114 pulsotypes, single-source pulsotypes, with >1 isolate from bovine bulk milk, caprine bulk milk, raw-milk products, or human blood cultures, included 33 (28.2%), 37 (32.5%), 11 (40.7%), and 3 (7.7%) isolates, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Distribution of Staphylococcus aureus isolates belonging to 35 pulsotypes to which more than one S. aureus isolate was assigneda

| Pulsotype | Cluster | Region(s) | No. of isolates from the following sourceb:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bovine | Caprine | Raw | Mastitis | Human bc | All | |||

| BC1 | 32 | A, B, G | 7 | 1 | 1 | 9 | ||

| BC2 | 32 | A, B, C, D | 4 | 4 | 1 | 9 | ||

| BC3 | 32 | A, B, G | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| BC4 | 34 | B, C, D, E, G | 6 | 12 | 1 | 19 | ||

| BC5 | 36 | A, B, C, D, E | 4 | 15 | 7 | 1 | 27 | |

| BC6 | 36 | B, C, D, E | 3 | 7 | 1 | 11 | ||

| BC7 | 36 | A, C, D, F, G | 21 | 1 | 1 | 23 | ||

| BC8 | 42 | A, C, D, E | 1 | 12 | 2 | 15 | ||

| BC9 | 36 | A, F | 4 | 1 | 5 | |||

| B1 | 22 | F | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| B6 | 17 | C | 3 | 3 | ||||

| B10 | 8 | G | 2 | 2 | ||||

| B11 | 45 | A | 2 | 2 | ||||

| B17 | 35 | C, D | 2 | 2 | ||||

| B19 | 32 | A | 2 | 2 | ||||

| B32 | 34 | D, F, G | 11 | 1 | 12 | |||

| B33 | 32 | A, G | 2 | 2 | ||||

| B41 | 30 | D, F, G | 16 | 16 | ||||

| B45 | 29 | C | 2 | 2 | ||||

| B60 | 41 | A | 2 | 2 | ||||

| C4 | 35 | B, D, E | 5 | 5 | ||||

| C5 | 36 | B, D | 2 | 2 | ||||

| C8 | 36 | A, D | 2 | 2 | ||||

| C9 | 36 | A, D, E | 3 | 3 | ||||

| C14 | 35 | A | 2 | 2 | ||||

| C26 | 33 | A | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||

| C37 | 42 | A, C, D | 15 | 15 | ||||

| C38 | 42 | A, D | 4 | 4 | ||||

| C40 | 44 | B | 2 | 2 | ||||

| C43 | 42 | B, C | 2 | 2 | ||||

| P1 | 17 | 4 | 4 | |||||

| P3 | 10 | 4 | 4 | |||||

| P12 | 24 | 3 | 3 | |||||

| H9 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |||||

| H36 | 51 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

Pulsotypes are listed with respect to the cluster number to which they belong, the regions in which they were found, and the number of isolates from each source.

Sources were bovine bulk milk, caprine bulk milk, raw-milk products, cases of ruminant mastitis, and human blood cultures (bc).

Fifty-one (43.6%) bovine bulk milk isolates and 57 (50.0%) caprine bulk milk isolates belonged to nine pulsotypes common to both sources. Ten (37.0%) of the raw-milk product isolates and five of the (55.6%) ruminant mastitis isolates belonged to three and five of these nine pulsotypes, respectively (Table 1). One bovine mastitis isolate belonged to a bovine-bulk-milk pulsotype (B32), and one caprine mastitis isolate belonged to a caprine-bulk-milk pulsotype (C26). Three human blood culture isolates belonged to two different pulsotypes that contained a bovine bulk milk isolate (B1) and a raw-milk product isolate (H36), respectively.

Single-isolate-pulsotypes included 21 (17.9%), 18 (15.8%), 5(18.5%), and 33 (84.6%) isolates from bovine bulk milk, caprine bulk milk, raw-milk products, and human blood cultures, respectively. Two of the ruminant mastitis isolates belonged to two pulsotypes that were not observed among isolates from other sources.

All pulsotypes to which more than four S. aureus bulk milk isolates were assigned included isolates from at least two different geographic regions.

Cluster analysis of the 306 S. aureus isolates resulted in a dendrogram where isolates clustered together at 26.9% similarity. Fifty-four clusters were identified with an 80% similarity cutoff. Isolates from bovine bulk milk, caprine bulk milk, raw-milk products, ruminant mastitis, and human blood cultures were distributed in 22, 14, 10, 4, and 23 clusters, respectively.

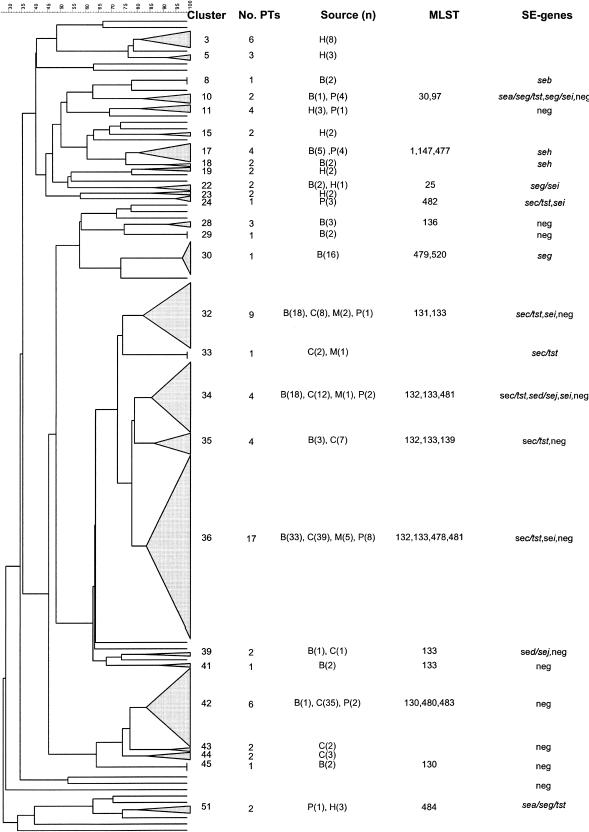

Clusters with >1 isolate are described in Fig. 2. Ten clusters (clusters 32 to 41), with 62.7% similarity, included 76 (65%) bovine bulk milk isolates, 71 (62.3%) caprine bulk milk isolates, 11 (40.7%) of the raw-milk product isolates, and all 9 ruminant mastitis isolates, but no human blood culture isolates. Twenty-seven branches contained single isolates from bovine bulk milk (n = 6), caprine bulk milk (n = 5), raw-milk products (n = 1), and human blood culture isolates (n = 15).

FIG. 2.

Dendrogram created from PFGE restriction profiles of 306 Staphylococcus aureus isolates from bovine bulk milk (B), caprine bulk milk (C), cases of ruminant mastitis (M), raw-milk products (P), and human blood cultures (H). The cluster cutoff was set at 80% similarity. Columns to the right of the dendrogram show the assigned cluster number, the number of different PTs observed within each cluster, the number of isolates from each source, and the multilocus STs and SE gene profiles observed among isolates in each cluster.

Within the 27 clusters with >1 isolate, 88 pairwise comparisons were identified where two isolates compared with each other differed by >6 bands.

MLST.

The 101 isolates tested by MLST could be divided into 22 different sequence types (Table 2). The allelic profiles of each ST and the allele sequences are available in the MLST database (http://www.mlst.net). Eighteen of the STs were submitted as new registrations to the database. New variant alleles of the arcC (n = 7), aroE (n = 3), glpF (n = 5), gmk (n = 1), pta (n = 4), tpi (n = 2), and yqiL (n = 3) genes were recognized.

TABLE 2.

Distribution of 101 Staphylococcus aureus isolates assigned to 22 different multilocus STsa

| STb | Allelic profile | COc | No. of isolates | No. of PTs | Region | No. of isolates from the following sourced:

|

SE gene profilee (no. of isolates) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | C | P | |||||||

| 131* | 40-66-46-2-7-50-18 | 1 | 1 | 1 | A | 1 | sei (1) | ||

| 132* | 6-66-47-2-7-50-18 | 1 | 14 | 3 | A,D,F | 14 | Neg (10), sed/sej (2), sei (2) | ||

| 133* | 6-66-46-2-7-50-18 | 1† | 45 | 20 | A,C | 14 | 25 | 6 | Neg (11), sec/tst (34) |

| 139* | 6-66-46-2-45-50-18 | 1 | 1 | 1 | A | 1 | sec/tst (1) | ||

| 478* | 54-66-46-2-7-50-18 | 1 | 1 | 1 | F | 1 | sec/tst (1) | ||

| 481* | 6-66-46-2-54-50-18 | 1 | 5 | 2 | D | 3 | 2 | sec/tst (5) | |

| 1 | 1-1-1-1-1-1-1 | 2† | 2 | 2 | C | 2 | seh (2) | ||

| 147* | 1-1-1-36-1-1-1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | C | 1 | seh (1) | ||

| 477* | 1-1-1-1-1-50-1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | seh (1) | |||

| 130* | 6-57-45-2-7-58-52 | 3† | 11 | 4 | A,C,D | 2 | 9 | Neg (11) | |

| 480* | 6-57-45-2-7-58-18 | 3 | 1 | 1 | D | Neg (1) | |||

| 483* | 6-57-63-2-7-58-52 | 3 | 1 | 1 | D | 1 | Neg (1) | ||

| 30 | 2-2-2-2-6-3-2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | sea/seg/tst (1) | |||

| 484* | 2-2-2-2-1-3-2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | sea/seg/tst (1) | |||

| 479* | 52-87-54-18-56-32-65 | 5 | 7 | 1 | D,F | 7 | seg (7) | ||

| 520* | 55-87-54-18-56-32-65 | 5 | 1 | 1 | D | 1 | seg (1) | ||

| 25 | 4-1-4-1-5-5-4 | — | 1 | 1 | F | 1 | sei/seg (1) | ||

| 97 | 3-1-1-1-7-5-3 | — | 1 | 1 | 1 | Neg (1) | |||

| 135* | 39-69-1-4-12-1-10 | — | 1 | 1 | C | 1 | sej/sed/sej/seg (1) | ||

| 136* | 38-55-45-18-38-14-2 | — | 1 | 1 | C | 1 | Neg (1) | ||

| 137* | 7-6-47-5-8-8-6 | — | 1 | 1 | C | 1 | sei/seg (1) | ||

| 482* | 59-79-66-2-62-76-71 | — | 2 | 1 | 2 | sei (2) | |||

STs are listed with respect to the allelic profile (www.mlst.net), the CC to which each ST belongs, the number of isolates assigned to each ST, the number of PTs observed among isolates from each ST, and the regions in which isolates belonging to each ST were found.

Asterisks indicate STs newly registered at www.mlst.net.

Daggers indicate predicted ancestors or founders of CC. —, singleton ST.

B, bovine bulk milk; C, caprine bulk milk; P, raw-milk products.

Neg, negative.

Seven of the STs included more than one isolate, and four of these included isolates from only one source. Sequence type 482 was unique to two isolates from raw-milk cheeses made from reindeer milk. With the exception of ST 481, STs with >2 isolates were found in more than one region.

eBURST analysis divided the 22 STs into five CC. Predicted founders were proposed for CC1, CC2, and CC3. The clonal complexes and their predicted founders are shown in Table 2. STs in CC2 were observed only for bovine bulk milk isolates and an isolate from a raw cow-milk cheese. STs in CC5 were also observed only in bovine bulk milk isolates. Six STs were defined as singletons.

eBURST analysis divided the 366 STs registered in the MLST database into 35 clonal complexes (results not shown). Three of these clonal complexes were exactly equivalent to CC1, CC3, and CC5 of the first analysis. STs 1, 147, and 477, STs 30 and 484, ST 25, ST 97, and ST 137 were grouped in five different clonal complexes that also included STs observed in S. aureus strains obtained from human disease or healthy human carriers (www.mlst.net). STs 135, 136, and 482 were defined as singletons in the entire database as well as in our study.

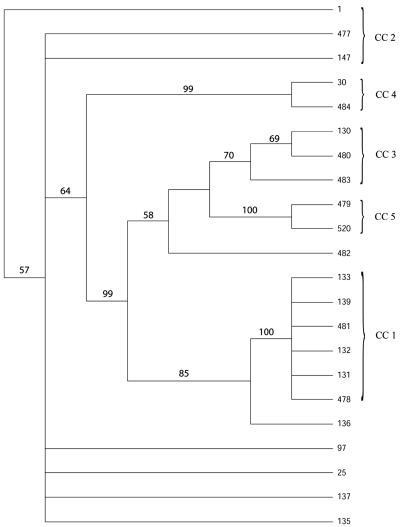

Phylogenetic analyses of MLST sequences.

By phylogenetic analyses, seven most-parsimonious trees were created for the concatenated sequence of all seven genes. The strict consensus tree is shown, with bootstrap values, in Fig. 3. It was largely congruent with the most-parsimonious trees and with trees created for each of the seven individual genes (results not shown). The hypothesized evolution of the 22 sequence types, as observed in the phylogenetic trees, also corresponded with the division into clonal complexes.

FIG. 3.

The strict consensus tree created from phylogenetic analyses of 22 Staphylococcus aureus STs, shown with bootstrap values of particular branches. ST 1 was chosen as the root of the tree. The identification number of each ST is given on the right (www.mlst.net), and brackets indicate which STs are included in each CC.

Correspondence between PFGE and MLST results.

The 101 S. aureus isolates genotyped by MLST and PFGE could be divided into 22 STs and 39 pulsotypes, respectively. Isolates with identical STs could belong to different pulsotypes (Table 2)and be assigned to different PFGE clusters (Table 2; Fig. 2.). In nine situations, isolates assigned to the same pulsotype belonged to different STs. However, in eight of these situations, the STs belonged to the same clonal complex. In the ninth case, two isolates assigned to pulsotype P3 belonged to STs 30 and 97, respectively, which differ from one another at all seven genes. In general, only STs belonging to the same clonal complex were found within single clusters (clusters 17, 30, 32, 34, 35, 36, and 42).

Assay of enterotoxin genes by multiplex PCR.

Results from the m-PCR conducted in the present study are shown in Table 3 together with results from isolates previously tested (20). With the exception of six pulsotypes (Table 4), isolates with indistinguishable PFGE banding patterns had the same SE gene profile.

TABLE 3.

Distribution of SE genes sea to see, seg to sej, and tst (encoding toxic shock syndrome toxin) in S. aureus isolates from different sourcesa

| Source (n) | No. (%) of isolates positive for different combinations of SE genes

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any SE gene | sea/seg/tst | seb | sec/tst | sed/sej | seg | sei | seg/sei | seh | sed/seg/sei/sej | |

| Bovine bulk milk (117) | 59 (50.4) | 2 (1.7) | 23 (19.7) | 3 (2.6) | 17 (14.5) | 3 (2.6) | 3 (2.6) | 7 (6) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Caprine bulk milk (114) | 65 (57) | 64 (56) | 1 (0.9) | |||||||

| Raw-milk products (27) | 18 (67) | 2 (7.4) | 9 (33.3) | 2 (7.4) | 1 (3.7) | 4 (14.8) | ||||

| Total (258) | 142 (55) | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) | 96 (37.2) | 3 (1.2) | 17 (6.6) | 5 (1.9) | 5 (1.9) | 11 (4.3) | 1 (0.4) |

Results from the present study are presented together with results from a previous study (20).

TABLE 4.

Distribution of SE gene profiles among Staphylococcus aureus isolates in situations where isolates belonging to the same PT had different SE gene profiles

| PT | Total no. of isolates | No. of isolates with the following SE gene profile:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nega | sec/tst | sed/sej | sei | seg/sei | sea/seg/tst | ||

| BC4 | 19 | 2 | 17 | ||||

| BC5 | 26 | 1 | 25 | ||||

| BC7 | 22 | 21 | 1 | ||||

| B32 | 11 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||

| P3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| P12 | 3 | 1 | 2 | ||||

Neg, negative.

Ninety-three (96.8%) of the sec/tst-positive bulk milk and raw-milk product isolates belonged to PFGE clusters 32 to 41. Apart from one sei-positive and three sed/sej-positive isolates, the remaining 50 bulk milk and raw-milk product isolates in these 10 clusters were SE gene negative. All 38 isolates in cluster 42 were SE gene negative, and 35 of these were from caprine bulk milk. Sixteen of the 17 seg-positive isolates were assigned to the same pulsotype (B41) and belonged to cluster 30. The seh-positive isolates all belonged to clusters 17 and 18. The five sei/seg-positive isolates were spread over four clusters (cluster 7, 10, 22, and 31).

Isolates belonging to the same ST had the same SE gene profiles except for ST 132 and ST 133, and the SE gene profiles of isolates belonging to the same clonal complex generally corresponded (Table 2).

Penicillin resistance.

Seventeen (6.5%) of the 258 S. aureus isolates from bulk milk and raw-milk products were found to be resistant to penicillin. These comprised nine (7.7%), four (3.5%), and four (14.8%) of the isolates from bovine bulk milk, caprine bulk milk, and raw-milk products, respectively. The nine isolates from clinical cases of mastitis were penicillin sensitive.

Thirteen (76.4%) of the penicillin-resistant isolates belonged to 11 single-isolate-pulsotypes and 1 pulsotype that included two penicillin-resistant isolates alone. The remaining four (25%) isolates were indistinguishable by PFGE from penicillin-sensitive isolates. The penicillin-resistant isolates were distributed in 12 PFGE clusters.

Three penicillin-resistant isolates belonged to ST 132, and one penicillin-resistant isolate each belonged to ST 25, ST 30, ST 135, and ST 484.

Out of the 17 penicillin-resistant isolates, 6 were SE gene negative. The remaining isolates contained sea/seg/tst (n = 2), seb (n = 1), sec/tst (n = 1), sed/sej (n = 2), seh (n = 1), sed/seg/seg/sej (n = 1), and sei/seg (n = 3).

DISCUSSION

Staphylococcus aureus isolates from Norwegian bovine and caprine bulk milk were genotyped by PFGE, MLST, and m-PCR for SE genes. The isolates proved genetically diverse, and certain genotypes appeared to be source specific. Isolates with genetic profiles indistinguishable from those of bulk milk isolates were obtained from raw-milk products and cases of ruminant mastitis.

By PFGE, nine pulsotypes common to bulk milk isolates from both animal species included 44% and 50% of the bovine and caprine bulk milk isolates, respectively. Eight of these pulsotypes were included in 10 clusters (clusters 32 to 41) that contained more than half the bulk milk isolates, 40% of the raw-milk product isolates, and all the ruminant mastitis isolates. These findings agree with those of Mørk et al. (31), who genotyped 905 Norwegian S. aureus isolates from cases of bovine, caprine, and ovine mastitis by PFGE and found that between 50% and 60% of the bovine and caprine isolates belonged to pulsotypes common to both animal species.

MLST revealed 22 different STs, 4 of which were found in more than one geographic region. All the STs observed for isolates from PFGE clusters 32 to 41 belonged to CC1. Interestingly, ST 133, the most prevalent sequence type and the predicted founder of CC1, has been reported from cases of bovine mastitis in Portugal (7). Four of the presently observed STs (STs 1, 25, 30, and 97) have been reported previously from cases of human disease or from healthy human carriers (11), and another four (STs 137, 147, 477, and 484) are single-locus variants of STs reported for strains of human origin (www.mlst.net). The presence of strains assigned to these STs in bulk milk or in raw-milk products could reflect human contamination. This is, however, not conclusive, since S. aureus isolates from cases of bovine mastitis sometimes resemble human variants of S. aureus more closely than other bovine variants (15).

The phylogenetic analyses verified that, in general, STs within one clonal complex were more closely related to each other than to STs of other clonal complexes. Sequence types in CC1, CC4, and CC5 were grouped with very high bootstrap support, and STs in CC3 were grouped with moderately high bootstrap support. The fact that CC1, CC3, and CC5 of the STs presently observed remained unchanged when the entire S.aureus database was analyzed by eBURST may reflect the limited number of S. aureus strains from animals that are registered in the MLST database.

Overall, sec was the SE gene most commonly observed in isolates from bovine and caprine bulk milk, and it was always observed together with tst. The coexistence of sec and tst, and the coproduction of SEC and TSST-1, is frequently observed in S. aureus isolates from cases of ruminant mastitis (1, 23, 41) and probably reflects the colocation of these genes on the bovine S. aureus pathogenicity island (14). The frequent presence of potentially SE producing S. aureus strains in raw milk and raw-milk products is a concern, since these may pose a public-health risk to consumers.

Bovine bulk milk isolates were placed in more clusters (22 versus 14), were assigned to more STs, and contained a greater diversity of SE genes than isolates from caprine bulk milk. The greater genetic diversity of bovine bulk milk isolates could reflect the larger bovine than caprine population in Norway or differences in husbandry systems for the two species. Because more than half the bulk milk isolates clustered with >60% similarity in 10 clusters that contained all the mastitis isolates, almost all the sec/tst-positive isolates, only STs belonging to CC1, and no human blood culture isolates, it could be hypothesized that these clusters represent ruminant-specialized S. aureus. Although isolates from bovine and caprine bulk milk shared certain genetic profiles, more host-specific pulsotypes were observed than common pulsotypes. The present results thus suggest that S. aureus isolates from cows and goats represent separate genetic populations with some overlap and some degree of relatedness. It seems feasible that ruminant S. aureus differs from human S. aureus but that an additional level of host specialization exists within the strains that infect ruminants.

Overall, the results for SE genes from the three genotyping methods, PFGE, MLST, and m-PCR, correlated. In general, isolates assigned to the same pulsotype had the same SE gene profile, isolates with identical SE gene profiles clustered together, and isolates within clonal complexes had the same SEgene profile. Furthermore, isolates within clusters almost always differed by six bands or fewer, and STs observed within single PFGE clusters generally belonged to the same clonal complex. This shows that genetically related isolates were successfully grouped with an 80% cluster cutoff. Although PFGE is a very useful tool for tracking particular S. aureus strains, MLST provides data on the basis of which evolutionary relationships may be inferred and conveniently allows direct comparison with results from other laboratories. In the present study, the existence of source specificity among certain S. aureus genotypes was more apparent by MLST than by PFGE.

According to criteria proposed by Tenover et al. (43), strains that differ by three bands or fewer by PFGE are likely to be closely related. The authors emphasized that these criteria apply to epidemiologically related isolates, and this is underlined by the present observation that two isolates assigned to the same pulsotype were assigned to STs 30 and 97, respectively, differing at each of the seven loci.

Penicillin resistance was rare among the isolates studied. In a previous report from Norway, 5% of S. aureus from clinical cases of bovine mastitis and 5% and 1% of S. aureus isolates obtained from bovine and caprine bulk milk, respectively, were penicillin resistant (4). The fact that most of the penicillin-resistant bulk milk isolates belonged to single-isolate pulsotypes suggests that penicillin resistance can be acquired by a variety of different S. aureus strains but does not confer a survival or transmission advantage under Norwegian conditions. In two studies, which included the 39 human blood culture isolates presently genotyped, penicillin resistance was observed in 50% to 70% of S. aureus isolates obtained from human blood cultures (25, 26). The difference in the frequency of penicillin resistance between S.aureus strains of ruminant versus human origin is remarkable. The restricted use of antibiotics in Norwegian dairy production and the culling of persistently infected animals may have contributed to the low frequency of penicillin resistance among bulk milk isolates. The spread of penicillin-resistant S. aureus through raw-milk products appears to be a minor public-health hazard in Norway.

Seven of the 9 ruminant mastitis isolates and 10 isolates from raw-milk products were assigned to pulsotypes that were also observed among bulk milk isolates. Most of these pulsotypes included a relatively large number of isolates and were geographically widespread. The findings support the expectation that S. aureus from infected udders may contaminate bulk milk and, subsequently, raw-milk products. It has been estimated that approximately 22% of Norwegian dairy cows shed S. aureus in their milk (40). These animals are likely to be a significant source of bulk milk contamination.

By PFGE the human blood culture isolates were diverse. They appeared mostly in single-isolate clusters and showed little similarity to isolates from other sources. The fact that human isolates were different from ruminant isolates supports the concept of host specificity among S. aureus strains, as suggested by others (17, 21, 32), although one could argue that this may be as much a question of host susceptibility as of bacterial host specificity. However, in the present study, the isolates of human origin were collected from specific disease cases in hospitals and may not reflect the natural S. aureus population in Norwegian humans today. Nevertheless, in two situations, blood culture isolates had the same pulsotype as isolates from other sources, confirming that S. aureus genotypes similar to the blood culture isolates may, in fact, contaminate bulk milk and raw-milk products.

The present study shows that certain S. aureus genotypes, with a wide geographic distribution, are frequently found in Norwegian bovine and caprine bulk milk. Although a large fraction of S. aureus isolates from bovine and caprine bulk milk share common genetic characteristics, source-specific types do exist. S. aureus strains with genotypes indistinguishable from those of strains from cases of ruminant mastitis are frequently found in bulk milk, and S. aureus strains in bulk milk appear to be a likely source of raw-milk product contamination.

Acknowledgments

The Norwegian Research Council is acknowledged for economic support of this work (grant 141197/130). We also thank COST, FEMS, and Pasteurlegatet (The Pasteur Legacy) for economic contributions.

We are most grateful to Torill Alvestad for technical assistance, to Arne Holst Jensen for helping with the phylogenetic analyses, and to Truls M. Leegaard for the strains of human origin.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akineden, O., C. Annemüller, A. A. Hassan, C. Lämmler, W. Wolter, and M. Zschöck. 2001. Toxin genes and other characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from milk of cows with mastitis. Clin. Diagn. Lab Immunol. 8:959-964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anonymous. 2003. Staphylococcal enterotoxins in milk products, particularly cheeses. European Commission, Health and Consumer Protection Directorate-General. Opinion of the Scientific Committee on Veterinary Measures Relating to Public Health. European Commission, Brussels, Belgium.

- 3.Bergan, T., J. N. Bruun, A. Digranes, E. Lingaas, K. K. Melby, and J. Sander. 1997. Susceptibility testing of bacteria and fungi. Report from the Norwegian Working Group on Antibiotics. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. Suppl. 103:1-36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blix, H. S., K. Grave, E. Heldal, M. Hofshagen, H. Kruse, J. Lassen, A. Nødtvedt, P. Sandven, G. S. Simonsen, and M. Steinbakk. 2000. Consumption of antimicrobial agents and occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in Norway. NORM/NORM-VET, Oslo and Tromsø, Norway.

- 5.Casciano, R., L. Alberghini, A. Peccio, A. Serraino, and R. Rosmini. 2003. Typing of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from raw milk. Vet. Res. Commun. 27(Suppl. 1):289-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiou, C. S., H. L. Wei, and L. C. Yang. 2000. Comparison of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and coagulase gene restriction profile analysis techniques in the molecular typing of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2186-2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Couto, I., A. I. R. P. Castro, S. F. F. Pereira, R. Bexiga, C. L. Vilela, M. C. Queiroga, A. Marinho, A. Mendonça, R. Maurício, I. Santos-Sanches, and H. de Lencastre. 2004. Molecular characterisation of Staphylococcus aureus strains causing sub-clinical bovine mastitis in Portugal, p. 245. In Proceedings of the 11th International Symposium on Staphylococci and Staphylococcal Infections, Charleston, S.C., 24 to 27 October 2004.

- 8.De Buyser, M. L., B. Dufour, M. Maire, and V. Lafarge. 2001. Implication of milk and milk products in food-borne diseases in France and in different industrialised countries. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 67:1-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devriese, L. A. 1984. A simplified system for biotyping Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from animal species. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 56:215-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dinges, M. M., P. M. Orwin, and P. M. Schlievert. 2000. Exotoxins of Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:16-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feil, E. J., J. E. Cooper, H. Grundmann, D. A. Robinson, M. C. Enright, T. Berendt, S. J. Peacock, J. M. Smith, M. Murphy, B. G. Spratt, C. E. Moore, and N. P. Day. 2003. How clonal is Staphylococcus aureus? J. Bacteriol. 185:3307-3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felsenstein, J. 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39:783-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitzgerald, J. R., W. J. Meaney, P. J. Hartigan, C. J. Smyth, and V. Kapur. 1997. Fine-structure molecular epidemiological analysis of Staphylococcus aureus recovered from cows. Epidemiol. Infect. 119:261-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzgerald, J. R., S. R. Monday, T. J. Foster, G. A. Bohach, P. J. Hartigan, W. J. Meaney, and C. J. Smyth. 2001. Characterization of a putative pathogenicity island from bovine Staphylococcus aureus encoding multiple superantigens. J. Bacteriol. 183:63-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fitzgerald, J. R., D. E. Sturdevant, S. M. Mackie, S. R. Gill, and J. M. Musser. 2001. Evolutionary genomics of Staphylococcus aureus: insights into the origin of methicillin-resistant strains and the toxic shock syndrome epidemic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:8821-8826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fox, L. K., M. Gershman, D. D. Hancock, and C. T. Hutton. 1991. Fomites and reservoirs of Staphylococcus aureus causing intramammary infections as determined by phage typing: the effect of milking time hygiene practices. Cornell Veterinarian 81:183-193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilot, P., and W. van Leeuwen. 2004. Comparative analysis of agr locus diversification and overall genetic variability among bovine and human Staphylococcus aureus isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1265-1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jablonski, L. M., and G. A. Bohach. 1997. Staphylococcus aureus, p. 353-375. In M. P. Doyle, L. R. Beuchat, and T. J. Montville (ed.), Food microbiology fundamentals and frontiers. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 19.Jarraud, S., M. A. Peyrat, A. Lim, A. Tristan, M. Bes, C. Mougel, J. Etienne, F. Vandenesch, M. Bonneville, and G. Lina. 2001. egc, a highly prevalent operon of enterotoxin gene, forms a putative nursery of superantigens in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Immunol. 166:669-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jørgensen, H. J., T. Mørk, H. R. Høgåsen, and L. M. Rørvik. 2005. Enterotoxigenic Staphylococcus aureus in bulk milk in Norway. J. Appl. Microbiol. 99:158-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kapur, V., W. M. Sischo, R. S. Greer, T. S. Whittam, and J. M. Musser. 1995. Molecular population genetic analysis of Staphylococcus aureus recovered from cows. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:376-380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaufmann, M. E. 1998. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, p. 33-50. In N. Woodford and A. P. Johnson (ed.), Molecular bacteriology. Humana Press Inc., Totowa, N.J. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Kenny, K., R. F. Reiser, F. D. Bastida-Corcuera, and N. L. Norcross. 1993. Production of enterotoxins and toxic shock syndrome toxin by bovine mammary isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:706-707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuroda, M., T. Ohta, I. Uchiyama, T. Baba, H. Yuzawa, I. Kobayashi, L. Cui, A. Oguchi, K. Aoki, Y. Nagai, J. Lian, T. Ito, M. Kanamori, H. Matsumaru, A. Maruyama, H. Murakami, A. Hosoyama, Y. Mizutani-Ui, N. K. Takahashi, T. Sawano, R. Inoue, C. Kaito, K. Sekimizu, H. Hirakawa, S. Kuhara, S. Goto, J. Yabuzaki, M. Kanehisa, A. Yamashita, K. Oshima, K. Furuya, C. Yoshino, T. Shiba, M. Hattori, N. Ogasawara, H. Hayashi, and K. Hiramatsu. 2001. Whole genome sequencing of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 357:1225-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leegaard, T. M., L. Bevanger, R. Jureen, T. Lier, K. K. Melby, D. A. Caugant, F. L. Oddvar, and E. A. Høiby. 2001. Antibiotic sensitivity still prevails in Norwegian blood culture isolates. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 18:99-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leegaard, T. M., E. Vik, D. A. Caugant, L. O. Froholm, and E. A. Høiby. 1999. Low occurrence of antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli and staphylococci isolated from blood cultures in two Norwegian hospitals in 1991-92 and 1995-96. APMIS 107:1060-1068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Letertre, C., S. Perelle, F. Dilasser, and P. Fach. 2003. Identification of a new putative enterotoxin SEU encoded by the egc cluster of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Appl. Microbiol. 95:38-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lina, G., G. A. Bohach, S. P. Nair, K. Hiramatsu, E. Jouvin-Marche, and R. Mariuzza. 2004. Standard nomenclature for the superantigens expressed by Staphylococcus. J. Infect. Dis. 189:2334-2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Løvseth, A., S. Loncarevic, and K. Berdal. 2004. Modified multiplex PCR method for detection of pyrogenic exotoxin genes in staphylococcal isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:3869-3872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin, M. C., J. M. Fueyo, M. A. Gonzalez-Hevia, and M. C. Mendoza. 2004. Genetic procedures for identification of enterotoxigenic strains of Staphylococcus aureus from three food poisoning outbreaks. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 94:279-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mørk, T., T. Tollersrud, B. Kvitle, H. J. Jørgensen, and S. Waage. 2005. Comparison of Staphylococcus aureus genotypes recovered from cases of bovine, ovine, and caprine mastitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:3979-3984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Musser, J. M., and R. K. Selander. 1990. Genetic analysis of natural populations of Staphylococcus aureus, p. 59-67. In R. Novick and R. A. Skurray (ed.), Molecular biology of the staphylococci. VCH Publishers, New York, N.Y.

- 33.Omoe, K., D. L. Hu, H. Takahashi-Omoe, A. Nakane, and K. Shinagawa. 2003. Identification and characterization of a new staphylococcal enterotoxin-related putative toxin encoded by two kinds of plasmids. Infect. Immun. 71:6088-6094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orwin, P. M., J. R. Fitzgerald, D. Y. Leung, J. A. Gutierrez, G. A. Bohach, and P. M. Schlievert. 2003. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin L. Infect. Immun. 71:2916-2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orwin, P. M., D. Y. Leung, H. L. Donahue, R. P. Novick, and P. M. Schlievert. 2001. Biochemical and biological properties of staphylococcal enterotoxin K. Infect. Immun. 69:360-366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orwin, P. M., D. Y. Leung, T. J. Tripp, G. A. Bohach, C. A. Earhart, D. H. Ohlendorf, and P. M. Schlievert. 2002. Characterization of a novel staphylococcal enterotoxin-like superantigen, a member of the group V subfamily of pyrogenic toxins. Biochemistry 41:14033-14040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peacock, S. J., G. D. de Silva, A. Justice, A. Cowland, C. E. Moore, C. G. Winearls, and N. P. Day. 2002. Comparison of multilocus sequence typing and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis as tools for typing Staphylococcus aureus isolates in a microepidemiological setting. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3764-3770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sabour, P. M., J. J. Gill, D. Lepp, J. C. Pacan, R. Ahmed, R. Dingwell, and K. Leslie. 2004. Molecular typing and distribution of Staphylococcus aureus isolates in Eastern Canadian dairy herds. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:3449-3455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scherrer, D., S. Corti, J. E. Muehlherr, C. Zweifel, and R. Stephan. 2004. Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from raw bulk-tank milk samples of goats and sheep. Vet. Microbiol. 101:101-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sølverød, L., and O. Østerås. 2001. The Norwegian Survey of Subclinical Mastitis during 2000, p. 126-130. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium on Mastitis and Milk Quality. American Association of Bovine Practitioners, Rome, Ga., and National Mastitis Council, Madison, Wis.

- 41.Stephan, R., C. Annemuller, A. A. Hassan, and C. Lammler. 2001. Characterization of enterotoxigenic Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from bovine mastitis in north-east Switzerland. Vet. Microbiol. 78:373-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, and R. V. Goering, et al. 1997. How to select and interpret molecular strain typing methods for epidemiological studies of bacterial infections: a review for healthcare epidemiologists. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 18:426-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zadoks, R. N., W. B. van Leeuwen, D. Kreft, L. K. Fox, H. W. Barkema, Y. H. Schukken, and A. van Belkum. 2002. Comparison of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from bovine and human skin, milking equipment, and bovine milk by phage typing, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, and binary typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3894-3902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]