Abstract

In a previous study (M. Sasaki, J. Maki, K. Oshiman, Y. Matsumura, and T. Tsuchido, Biodegradation 16:449-459, 2005), the cytochrome P450 monooxygenase system was shown to be involved in bisphenol A (BPA) degradation by Sphingomonas sp. strain AO1. In the present investigation, we purified the components of this monooxygenase, cytochrome P450 (P450bisd), ferredoxin (Fdbisd), and ferredoxin reductase (Redbisd). We demonstrated that P450bisd and Fdbisd are homodimeric proteins with molecular masses of 102.3 and 19.1 kDa, respectively, by gel filtration chromatography analysis. Spectroscopic analysis of Fdbisd revealed the presence of a putidaredoxin-type [2Fe-2S] cluster. P450bisd, in the presence of Fdbisd, Redbisd, and NADH, was able to convert BPA. The Km and kcat values for BPA degradation were 85 ± 4.7 μM and 3.9 ± 0.04 min−1, respectively. NADPH, spinach ferredoxin, and spinach ferredoxin reductase resulted in weak monooxygenase activity. These results indicated that the electron transport system of P450bisd might exhibit strict specificity. Two BPA degradation products of the P450bisd system were detected by high-performance liquid chromatography analysis and were thought to be 1,2-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-2-propanol and 2,2-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1-propanol based on mass spectrometry-mass spectrometry analysis. This is the first report demonstrating that the cytochrome P450 monooxygenase system in bacteria is involved in BPA degradation.

Bisphenol A (BPA) [2,2-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)propane] is one of the industrially important compounds for production of polycarbonates, epoxy resins, and other plastics, and worldwide annual consumption of this compound is increasing. However, BPA is strongly suspected to be an endocrine disruptor (7, 16, 26) and exhibits slight or moderate toxicity in aquatic organisms (39). Sugita-Konishi et al. (42) recently also reported that BPA is immunotoxic and reduces the nonspecific host defense to a level that causes acute toxicity in mice. Furthermore, Colborn and colleagues (4) reported that BPA is widely distributed in rivers, seas, streams, and soils. These reports have proposed that information about the biological conversion of BPA is useful for understanding the fate of this compound in the environment and also for establishing techniques to purge and remove BPA from the environment.

Biological transformation of BPA has been reported by many researchers. In mammals, it has been established that BPA is converted to a glucuronide conjugate and a sulfate conjugate in rats (30, 31). In plants, cells of Eucalyptus perriniana and tobacco BY-2 metabolize BPA to its hydroxyl and/or glycosyl products (8, 24). However, it has been proposed that BPA in the environment is decomposed mainly by microorganisms (5, 39). Yim et al. (48) showed that in fungi BPA was metabolized to BPA-O-β-d-glucopyranoside. Several investigators have also reported that lignin-degrading enzymes, including lignin peroxidase, manganese peroxidase, and/or laccase from basidiomycetes, react with BPA (6, 9, 34, 44, 45, 46). However, it is not clear how these systems can degrade BPA into small molecules, because some of them also concomitantly produce polymerized BPA (34, 45, 46). Several BPA-degrading bacteria have been isolated, including gram-negative bacterial strains MV1 (20, 38) and WH1 (33) and Sphingomonas sp. strains FJ-4 (12) and AO1 (35). These strains can grow in a basal mineral salt medium containing BPA as the sole carbon source and can metabolize BPA to CO2, H2O, and cellular components. Some metabolites from BPA have already been identified, and the data have suggested that two metabolic pathways are involved in BPA degradation (12, 35, 38). However, it is still not clear which enzymes and genes are involved in the BPA degradation pathway.

In a previous report, we demonstrated that the cytochrome P450 monooxygenase system is likely to be involved in the initial hydroxylation of BPA in Sphingomonas sp. strain AO1 (35). Furthermore, BPA degradation by cells was induced by BPA only in the basal mineral salt medium, not in LB medium (35). It was also demonstrated that the activity of the cytochrome P450 monooxygenase system was very unstable and that addition of 1 mM sodium dithionite prevented inactivation of the system, although sodium dithionite had an inhibitory effect on its activity (35).

Most bacterial cytochrome P450 monooxygenase systems are class I systems and require a flavin adenine dinucleotide-containing NADH-dependent reductase (ferredoxin reductase) and an iron-sulfur redoxin (ferredoxin) (19, 23, 47). These cytochrome P450 monooxygenase systems are able to catalyze the hydroxylation, epoxidation, sulfoxidation, or dealkylation of a wide range of xenobiotic compounds, such as medicines, perfumes, carcinogens, pollutants, and pesticides (http://www.icgeb.org/∼p450srv/). In this study, we purified and characterized cytochrome P450, ferredoxin, and ferredoxin reductase from strain AO1 and clearly demonstrated that these enzymes are involved in BPA degradation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strain and growth conditions.

Sphingomonas sp. strain AO1 is a BPA degrader that was isolated from firm soil in Tsukuba, Japan (35). This strain was grown in LB medium (10 g Bacto tryptone per liter, 5 g Bacto yeast extract per liter, 5 g NaCl per liter; pH 7.2). Cells were cultivated at 30°C with shaking at 120 rpm. Cell growth was monitored by determining the optical density at 650 nm with a U-2001 double-beam spectrophotometer (Hitachi High-Technologies Co., Tokyo, Japan).

Assays for components of a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase system.

(i) Cytochrome P450. Reduced cytochrome P450 carbon monoxide (CO) difference spectra were measured by the method described by Omura and Sato (27) to determine the cytochrome P450 concentration. Proteins were reduced with 1 mg · ml−1 sodium dithionite. Absorption spectra of enzyme solutions were recorded with a U-2001 spectrophotometer. The amount of cytochrome P450 was calculated from the absorbance at 450 nm using the cytochrome P450 extinction coefficient, 91 mM−1 · cm−1 (27). When the conversion of cytochrome P450 to the P420 form was rapid, a second extinction coefficient, corresponding to P420, was used for determination of the amount of cytochrome P450 (37). This absorption coefficient is 176.5 mM−1 · cm−1 at 420 nm.

(ii) Ferredoxin.

The ferredoxin was detected at an absorbance of 450 nm. The ratio of absorbance at 450 nm to absorbance at 280 nm indicated the purity of ferredoxin.

(iii) Ferredoxin reductase.

Reductase activities were determined by measuring NADH consumption (extinction coefficient at 340 nm, 6,220 M−1 · cm−1) (41). The reaction mixture (1.0 ml), containing 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.6), 125 μM NADH, 250 μM potassium ferricyanide, and the enzyme solution, was maintained at room temperature. One unit of activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to oxidize 1.0 μmol of NADH per min.

Purification protocol.

All purification steps were performed at 4°C. Activity-containing fractions were stored at −20°C. The culture was harvested during the early stationary phase (optical density at 650 nm, ca. 8.0) and centrifuged at 9,200 × g at 4°C for 10 min. Strain AO1 cells (approximately 50 g [wet weight]) were washed twice with 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.6) and resuspended in 50 ml of buffer A (50 mM potassium phosphate buffer [pH 7.6]) containing 10% glycerol, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.1 mM EDTA. This cell suspension was sonicated in an ice-water bath (20 W; seven 1-min pulses with 1-min intervals) with a model 250 Sonifier (Branson Ultrasonics Co., Danbury, CT) to disrupt the cells. The cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 165,000 × g for 1 h, followed by centrifugation at 13,200 × g for 10 min, to obtain the crude extract.

The crude extract was applied to a DEAE-Sepharose column (DEAE-Sepharose CL-6B [Amersham Biosciences, Freiburg, Germany] in an econo column [column volume, 98 ml; column diameter, 2.5 cm; Bio-Rad, Osaka, Japan]) that was equilibrated with buffer A. The column was washed with 300 ml of buffer A containing 20 mM NaCl. Proteins were eluted by using two linear gradients, 20 to 500 mM NaCl and 0.5 to 1 M NaCl in buffer A, at a flow rate of 1.0 ml · min−1. Activity-containing fractions were collected, diluted with buffer A, and applied to a Super Q column (Super Q-TOYOPEARL 650 M ion-exchange resin [Tosoh Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan] in an econo column [column volume, 25 ml; column diameter, 2.5 cm; Bio-Rad]) that was equilibrated with buffer A. The column was washed with 150 ml of buffer A containing 20 mM NaCl. Proteins were eluted with a linear 20 to 500 mM NaCl gradient in buffer A. Activity-containing fractions were collected and applied to a UNO Q column (column volume, 1.3 ml; column diameter, 0.7 cm; Bio-Rad) that was equilibrated with buffer A. The column was washed with 20 ml of buffer A. Proteins were eluted with a linear 0 to 500 mM NaCl gradient in buffer A.

Protein analyses.

The protein concentration was determined with a BCA protein assay reagent kit (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL). The protein profile for each purification step was analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using 15% polyacrylamide gels (17). Proteins in gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R250. The native molecular weight of the purified protein was determined by gel filtration analysis using a Sephacryl S-200HR column (Amersham Biosciences). The N-terminal amino acid sequence of the protein, transferred to a Sequi-Blot polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad), was identified using a PPSQ-21 protein sequencer (Shimadzu Co., Kyoto, Japan).

BPA degradation assay.

The BPA degradation activity of the crude extract was measured by the method described previously (35). The BPA degradation activity of purified cytochrome P450 from strain AO1 was determined by the reconstituted enzyme assay. The reaction mixture contained 0.44 mM BPA, purified cytochrome P450 at various concentrations, 10 μM ferredoxin, 0.027 U reductase, and 1 mM NADH or NADPH in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0). The reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C, extracted with ethyl acetate, and analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (35). To determine the Km and kcat values, 1 mM NADH and BPA at concentrations of 0.21 to 0.87 mM were added to the reconstituted assay mixture. The enzymatic kinetic parameters were determined by nonlinear regression analysis using the GraphPad Prism 4.03 software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA).

HPLC analyses of BPA and its metabolites.

BPA and its metabolites were extracted from the BPA-containing solution with an equal volume of ethyl acetate. The ethyl acetate extract was evaporated with a CVE-2000 centrifugal evaporator (Tokyo Rikakikai Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at 40°C. The residue was redissolved in 20% acetonitrile. The concentrations of BPA and its metabolites were analyzed by HPLC performed with a TSK OD-4PW gel (C18 reverse-phase) column (length, 15 cm; inside diameter, 4.6 mm; Tosoh) (35). The metabolites were collected and concentrated by evaporation, and their structures were identified by the methods described below.

MS-MS analysis.

Mass spectra were obtained with a model API 3000 system (Applied Systems Co., Foster, CA) using the atmospheric pressure chemical ionization method. A mass spectrometry (MS) analysis (m/z 100 to 600) was carried out in the negative ionization mode. The structures of the metabolites were confirmed by comparing the fragmentation patterns of the mass spectra with those predicted for known compounds.

Chemicals.

Bacto tryptone and Bacto yeast extract were supplied by Difco Laboratories (Detroit, MI). NADH and NADPH were obtained from Oriental Yeast Industries Co. (Tokyo, Japan). Spinach ferredoxin and spinach ferredoxin-NADP+ oxidoreductase (spinach reductase) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). All other reagents used were products of Wako Pure Chemical Industries. The solvents used for HPLC analysis were HPLC grade.

RESULTS

Purification and characterization of cytochrome P450, ferredoxin, and ferredoxin reductase from strain AO1.

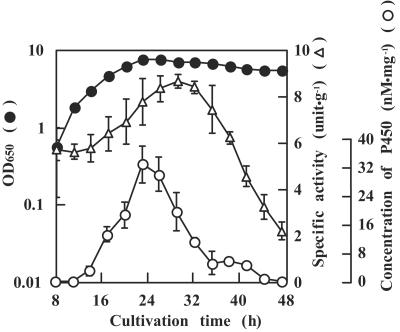

We have reported previously that the BPA degradation activity of crude extract from strain AO1 cells cultivated in LB medium is higher than that in the basal mineral salt medium containing 100 μg · ml−1 BPA (35). Therefore, LB medium was used for cultivation of strain AO1 cells in this study. The cytochrome P450 content in cells, which corresponded to the BPA degradation activity, gradually increased until the stationary phase and reached a maximum level at about 20 h (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

BPA-degrading activity and cytochrome P450 concentration in crude extract from strain AO1 cells cultivated in LB medium. The crude extract was incubated in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) buffer containing 1 mM NADH and 115 μg · ml−1 BPA for 15 min at 30°C. One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to degrade 1 μmol of BPA per min. The symbols indicate the optical density at 650 (OD650) and the specific activity and concentration of cytochrome P450 in the crude extract. The error bars indicate the standard deviations obtained for three independent experiments.

The cytochrome P450 monooxygenase system of strain AO1 was very unstable, and sodium dithionite prevented inactivation of the system, although sodium dithionite had an inhibitory effect on its activity (35). It has also been reported that cytochrome P450 monooxygenase systems are generally very unstable and that glycerol is an effective stabilizer for their activities (10, 28, 32). Therefore, we examined the effect of glycerol on the stability of the BPA degradation activity in strain AO1 cells. Addition of 10% glycerol to the crude extract resulted in retention of ca. 20 and 90% of the activity after 1 week of incubation at 4 and −20°C, respectively, without an inhibitory effect. Hence, glycerol at a concentration of 10% was used as a stabilizer instead of sodium dithionite.

The steps used for purification of cytochrome P450, ferredoxin, and ferredoxin reductase are summarized in Table 1. The purity index (R value) of purified cytochrome P450 was an A418/A280 ratio of 1.39, indicating homogeneity (1, 29). The purified cytochrome P450 and ferredoxin had molecular masses of 51.0 and 11.0 kDa, respectively, as determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis (data not shown), and 102.3 and 19.1 kDa, respectively, as determined by gel filtration chromatography. Both proteins were dimeric. Ferredoxin reductase was partially purified by ion-exchange chromatography. The resulting activity-containing fraction did not contain any cytochrome P450 and ferredoxin proteins, although other proteins were present (data not shown). The purified cytochrome P450, ferredoxin, and ferredoxin reductase from strain AO1 were designated P450bisd, Fdbisd, and Redbisd, respectively. The characteristics of these proteins were investigated in the experiments described below.

TABLE 1.

Purification of P450bisd, Fdbisd, and Redbisd

| Purification step | P450bisd

|

Fdbisd

|

Redbisd

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concn (mg/ml) | Amt of P450 (nmol/mg) | Yield (%) | Purification (fold) | Concn (mg/ml) | Purity index (A450/A280) | Yield (%) | Purification (fold) | Concn (mg/ml) | Sp act (U/mg) | Yield (%) | Purification (fold) | |

| Crude extract | 20.8 | 0.095 | 100 | 1.0 | 16.4 | 0.03 | 100 | 1.0 | 22.5 | 0.035 | 100 | 1.0 |

| DEAE-Sepharose | 5.5 | 0.34 | 60 | 3.6 | 4.2 | 0.08 | 63 | 2.4 | 4.7 | 0.084 | 32 | 2.4 |

| Super Q | 0.7 | 5.13 | 48 | 53.9 | 1.3 | 0.35 | 28 | 11.3 | 4.8 | 0.173 | 36 | 4.9 |

| UNO Q | 0.4 | 16.2 | 40 | 170.1 | 0.8 | 0.65 | 2 | 21.0 | 2.2 | 0.611 | 22 | 17.5 |

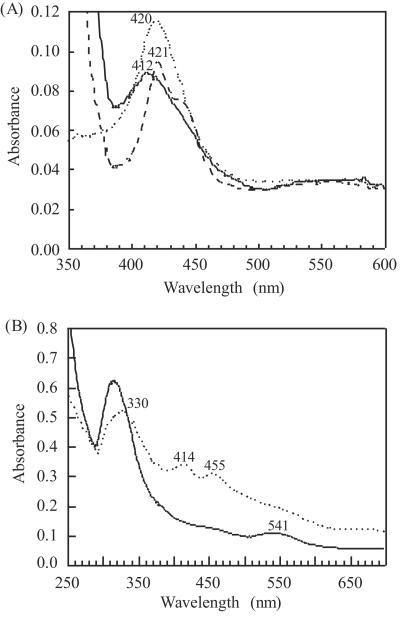

Spectroscopic properties of P450bisd and Fdbisd.

P450bisd and Fdbisd exhibited spectra characteristic of cytochrome P450 and ferredoxin (Fig. 2), suggesting that these proteins are cytochrome P450 and ferredoxin. The spectrum of oxidized P450bisd had an absorption peak at 420 nm (Fig. 2A), indicating that the iron in cytochrome P450 was in a low-spin state. The dithionite-reduced protein had maximum absorption at 412 nm, and bubbling with CO resulted in a change of the absorption peak to 421 nm with a shoulder around 450 nm (Fig. 2A). In general, CO-binding cytochrome P450s have an absorbance peak at 450 nm. In the case of P450bisd, the P450 form is very unstable and rapidly changes to the P420 form. It was also observed that the shoulder around 450 nm disappeared within 5 min. P420 peaks were observed in the cytochrome P450 spectrum, as discussed below.

FIG. 2.

Spectroscopic analysis of P450bisd and Fdbisd. The absorption spectra of P450bisd (A) and Fdbisd (B) were recorded using a 0.5-cm-light path cuvette. The spectra of the oxidized complex (dotted line), the sodium dithionite-reduced complex (solid line), and the subsequent CO-reduced complex (dashed line) are shown.

The absorbance spectrum of Fdbisd had three peaks, at 330, 414, and 455 nm, in the oxidized state (Fig. 2B). After reduction by sodium dithionite, strong decreases in the absorbance peaks at 414 and 455 nm and a new peak at 541 nm became evident (Fig. 2B). Reduced Fdbisd spontaneously changed to the oxidized form, suggesting that the reduced form was relatively unstable in the presence of O2.

Determination of N-terminal amino acids.

The N-terminal amino acid sequences of two purified proteins were determined. The sequences of P450bisd and Fdbisd were MNPQTLPVFPDLDIFSPEYAXNREKY (26 residues) and MPHIQVTTRDGEIRELDVAASGFLM (25 residues), respectively. Analyses with the BLAST program using the DDBJ database revealed no significant homologous proteins for either P450bisd or Fdbisd.

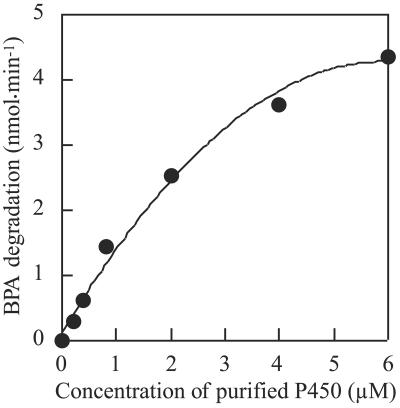

BPA degradation activity of the P450bisd monooxygenase system.

BPA degradation by P450bisd, Fdbisd, and Redbisd was assessed (Table 2). The BPA degradation activity was not detectable in the absence of Fdbisd and/or Redbisd and required both of these compounds, as well as P450bisd. NADH was a better electron donor for the P450bisd monooxygenase system than NADPH. BPA degradation activity correlated well with the concentration of P450bisd (Fig. 3). The Km and kcat values for BPA were 85 ± 4.7 μM and 3.9 ± 0.04 min−1, respectively, as determined by nonlinear regression analysis with the Michaelis-Menten reaction.

TABLE 2.

Degradation of BPA by P450bisd supplemented with ferredoxins and reductases

| Conditionsa | Activity (nmol substrate/ min/nmol P450)b

|

|

|---|---|---|

| NADH | NADPH | |

| P450bisd | < 0.04 | <0.04 |

| P450bisd + Fdbisd + spinach reductase | 0.52 ± 0.03 | 0.92 ± 0.06 |

| P450bisd + spinach ferredoxin + Redbisd | <0.04 | <0.04 |

| P450bisd + spinach ferredoxin + spinach reductase | <0.04 | 0.28 ± 0.03 |

| P450bisd + Fdbisd + Redbisd | 3.54 ± 0.17 | 0.09 ± 0.03 |

The reaction mixture contained 0.44 mM BPA, 2.0 μM P450bisd, 10 μM ferredoxin, 0.027 U reductase, and 1 mM NADH or NADPH in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0).

The values are means ± standard deviations for three trials.

FIG. 3.

Enzymatic analysis of the P450bisd monooxygenase system. BPA degradation activity was determined as described in Materials and Methods with 1 mM NADH, 0.44 mM BPA, and different amounts of P450bisd.

BPA degradation by P450bisd supplemented with spinach ferredoxin and reductase.

We examined whether spinach reductase and ferredoxin were available for the P450bisd monooxygenase system. It was observed that spinach reductase and ferredoxin were able to provide the electron (reductant power) from NADPH to the terminal component P450bisd. When the complete P450bisd monooxygenase system was used, a high BPA degradation rate was observed (Table 2). Spinach reductase could be substituted for Redbisd for BPA degradation, but the activity was significantly lower (Table 2).

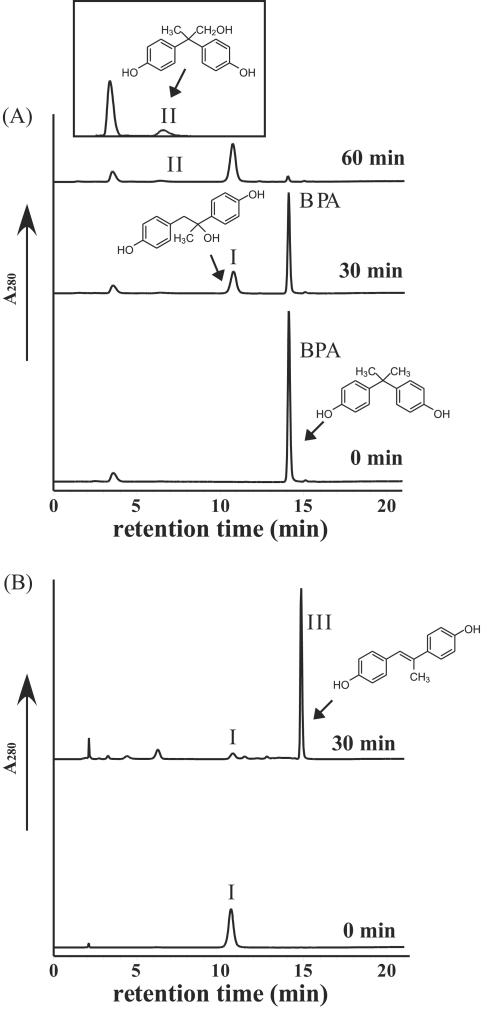

Identification of BPA degradation products obtained with the P450bisd monooxygenase system.

It was found in this study that the P450bisd monooxygenase system converts BPA. In the bacterial BPA degradation pathway described by other investigators, two pathways have been demonstrated. In one pathway BPA is converted to 1,2-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-2-propanol (molecular weight, 244), and in the other pathway BPA is converted to 2,2-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1-propanol (molecular weight, 244) (12, 35, 38). The BPA degradation products obtained with the P450bisd monooxygenase system were analyzed by HPLC (Fig. 4A). Peaks I and II were eluted at retention times of 6.4, and 10.7 min, respectively. The molecular ion peaks of both metabolites appeared at m/z 243 with a negative charge mode as determined by MS analysis. Furthermore, the ions of m/z 243 selected by the first MS were analyzed in the MS-MS mode. The ions of m/z 243 from peak I exhibited MS-MS peaks at m/z 243 (M-H) (1%), m/z 225 (M-H-H2O) (100%), m/z 210 (M-H-H2O-CH3) (14%), and m/z 135 (2-phenyl-propan-2-ol-H) (7%) (the values in parentheses are relative intensities). The ions of m/z 243 from peak II exhibited MS-MS peaks at m/z 243 (M-H) (5%), m/z 225 (M-H-H2O) (100%), m/z 210 (M-H-H2O-CH3) (16%), and m/z 135 (2-phenyl-propan-1-ol-H) (9%). These results suggested that these compounds might be 1,2-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-2-propanol and 2,2-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1-propanol.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of BPA metabolites by HPLC. The assay conditions with 1 mM NADH are described in Materials and Methods. (A) BPA degradation by the cytochrome P450 monooxygenase system. The inset shows an expanded peak II at 60 min. (B) Degradation of peak I by the crude extract (protein concentration, 8.0 mg · ml−1) from strain AO1. Peaks I, II, and III corresponded to 1,2-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-2-propanol, 2,2-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1-propanol, and 4,4′-dihydroxy-α-methylstilbene, as identified by MS-MS analyses, respectively.

Previously, we reported that 4,4′-dihydroxy-α-methylstilbene (molecular weight, 226), which was a metabolite from 1,2-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-2-propanol, accumulated during BPA degradation by a crude extract of strain AO1 (35). Therefore, the crude extract of strain AO1 was mixed with the BPA metabolite collected from peak I, and the resulting mixture was incubated at 30°C. The resulting solution was analyzed by HPLC, MS, and MS-MS. Peak III in Fig. 4B, which eluted at a retention time of 14.9 min, exhibited a molecular ion peak at m/z 225 with a negative charge mode as determined by MS analysis. The ions of m/z 225 from peak III exhibited MS-MS peaks at m/z 208 (M-H-OH) (80%), m/z 180 (C14H14-2H) (44%), m/z 117 (4-vinyl-phenol-H) (44%), and m/z 93 (phenol-H) (100%) (the values in parentheses are relative intensities), and the compound was predicted to be 4,4′-dihydroxy-α-methylstilbene. In the same reaction using the other metabolite collected from peak II, conversion from the metabolite was undetectable (data not shown). These results suggested that peaks I and II corresponded to 1,2-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-2-propanol and 2,2-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1-propanol, respectively.

DISCUSSION

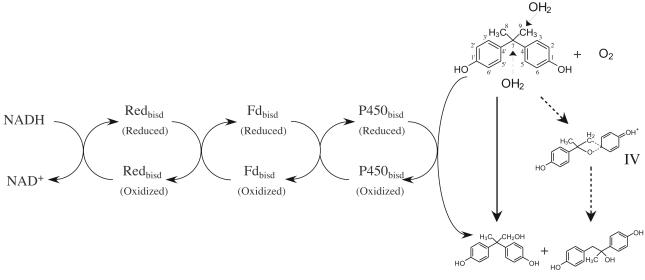

Here we report for the first time purification of BPA-degrading enzymes from bacteria, although biological degradation of BPA has been reported by many investigators. We also demonstrate that the P450bisd monooxygenase system is involved in the first step of BPA degradation by Sphingomonas sp. strain AO1 (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Electron flow in the BPA hydroxylation system and predicted enzymatic reaction of the P450bisd monooxygenase system. It is predicted that BPA is attacked by H2O with two strategies (solid and dashed lines).

The data indicated that the P450bisd monooxygenase system transformed BPA to two products, which were proposed to be 1,2-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-2-propanol (molecular weight, 244) and 2,2-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1-propanol (molecular weight, 244) (Fig. 5). Based on the general enzymatic specificity for the reaction, it is surprising that one enzyme catalyzed two reactions for one substrate. However, it has been reported previously that bacterial BPA degradation proceeds by two pathways and that BPA is converted to two metabolites (12, 35, 38), 1,2-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-2-propanol (the main metabolite) and 2,2-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1-propanol (a minor metabolite), which are the same products obtained from BPA in the in vitro enzymatic reaction. Spivack et al. (38) proposed that there might be an unstable common intermediate in these reactions and that the intermediate might be attacked by H2O at the methylene position and the benzylic position and converted to 2,2-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1-propanol and 1,2-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-2-propanol, respectively. However, it is hard to explain these consecutive reactions by the action of a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase system. Hence, we propose another hypothesis for the P450bisd monooxygenase reaction. It is generally known that cytochrome P450 catalyzes hydroxylation of a C atom. In the case of P450bisd monooxygenase with BPA as the substrate, it is predicted that either a C atom of a methyl group (C-8 or C-9) or the quaternary carbon (C-7) is attacked by H2O and hydroxylated. Hydroxylation of the methyl group converts BPA to 2,2-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1-propanol, and hydroxylation of the quaternary carbon may convert BPA to 1,2-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-2-propanol with transition of a phenol group. Formation of a novel intermediate, compound IV, may occur in the transition reaction. It is also proposed that cytochrome P450 monooxygenase systems are involved in bacterial BPA degradation. However, it is necessary to detect the intermediate for determination of the reaction mechanism of the P450bisd monooxygenase system.

The kinetic parameters for BPA hydroxylation by the P450bisd monooxygenase system were as follows: Km = 85 ± 4.7 μM and kcat = 3.9 ± 0.04 min−1. It has been demonstrated that the Km and kcat values for hydroxylation by other cytochrome P450s can be extremely variable (15, 18). P450bisd exhibited a low kcat value and appeared to be an ineffective enzyme for the hydroxylation of BPA. This might be attributed to the high affinity of binding to BPA or the use of a partially purified reductase. Indeed, P450bisd might be used for more efficient catalysis of different substrates.

It is not clear whether only the P450bisd monooxygenase system is involved in the first step of BPA degradation. However, the only detectable cytochrome P450 and ferredoxin in strain AO1 were P450bisd and Fdbisd, respectively. Furthermore, it was found that only Redbisd was involved in the P450bisd monooxygenase system, although two kinds of reductases were detected during purification (data not shown).

It has been reported previously that replacement of inherent ferredoxin or ferredoxin reductase with an analogous electron transfer protein markedly reduced the activities of cytochrome P450 monooxygenase systems, but the activities were still detectable (3, 25, 32). P450bisd can also utilize spinach reductase and ferredoxin as an electron transfer system for BPA degradation, indicating that the specificity of cytochrome P450 for electron donor components may be broad.

Characterization of P450bisd as a cytochrome P450 was confirmed by the CO-reduced spectrum of its purified protein. The absorption peak close to 450 nm is a fingerprint for reduced iron porphyrins having a thiolate ligand (40). The absorption spectrum of oxidized Fdbisd had peaks at 414 and 455 nm (Fig. 2B). This spectral feature has been observed previously in putidaredoxin-type [2Fe-2S] ferredoxin Fdx1 from Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1 (2), [2Fe-2S] ferredoxin from Escherichia coli (43), FdIV from Azotobacter vinelandii (14), and terpredoxin (Tdx) and putidaredoxin (Pdx) from Pseudomonas sp. (22), but not in the plant-type [2Fe-2S] ferredoxin. Tdx and Pdx, which are components of cytochrome P450 monooxygenase systems, have been the compounds that have been most extensively studied for hydroxylation of α-terpineol and camphor, respectively (29, 36). From these data, it is supposed that Fdbisd has a putidaredoxin-type [2Fe-2S] cluster.

In the reduced-CO difference spectrum of P450bisd, the absorption peak at 450 nm shifted quite rapidly to 420 nm. The P420 form is known to be enzymatically inactive (27, 28). The conversion of P450 to the P420 form is a common feature of cytochrome P450s, but it is usually observed only after chemical or physical treatment of cytochrome P450, such as exposure to high temperatures up to 60°C or to a pressure of 2 ×108 to 2.4 ×108 Pa (11, 21) or incubation with some detergents, proteases, acetone, neutral salts, or denaturants, such as urea or guanidine hydrochloride (13, 27, 28, 49). However, the fast spontaneous conversion of P450bisd to P420bisd appears to be an unusual feature. We previously reported that the BPA degradation activity of the crude extract from strain AO1 was very unstable and that this activity actually completely disappeared after incubation for 4 h at 4°C (35). Hence, the rapid conversion of P450bisd to the inactive form P420bisd may be a reason for the unstable BPA-degrading activity.

The N-terminal amino acid sequences of P450bisd and Fdbisd exhibit no significant similarity to any other proteins. To further investigate the properties of this P450bisd monooxygenase system and BPA degradation by strain AO1, it is necessary to clone the genes encoding P450bisd, Fdbisd, and Redbisd and construct an overexpression system for the P450bisd monooxygenase system. Furthermore, the structures of two BPA metabolites converted by the P450bisd monooxygenase system are still proposed structures and should be analyzed by H and C nuclear magnetic resonance.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yasuo Nagaoka of the Department of Biotechnology, Kansai University, for the MS-MS analyses and for helpful advice.

This work was supported by MEXT. HAITEKU (2002).

REFERENCES

- 1.Appleby, C. A. 1978. Purification of Rhizobium cytochromes P-450. Methods Enzymol. 52:157-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armengaud, J., and K. N. Timmis. 1997. Molecular characterization of Fdx1, a putidaredoxin-type [2Fe-2S] ferredoxin able to transfer electrons to the dioxin dioxygenase of Sphingomonas sp. RW1. Eur. J. Biochem. 247:833-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berg, A., M. Ingelman-Sundberg, and J. A. Gustafsson. 1979. Purification and characterization of cytochrome P-450meg. J. Biol. Chem. 254:5264-5271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colborn, T., D. Dumanoski, and J. P. Myers. 1996. Our stolen future. Dutton Signet New York, N.Y.

- 5.Dorn, P. B., C. S. Chou, and J. J. Getempo. 1987. Degradation of bisphenol A in natural waters. Chemosphere 16:1501-1507. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukuda, T., H. Uchida, Y. Takashima, T. Uwajima, T. Kawabata, and M. Suzuki. 2001. Degradation of bisphenol A by purified laccase from Trametes villosa. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 284:704-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaido, K. W., L. S. Leonard, S. Lovell, J. C. Gould, D. Babai, C. J. Portier, and D. P. McDonnell. 1997. Evaluation of chemicals with endocrine modulating activity in a yeast-based steroid hormone receptor gene transcription assay. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 143:205-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamada, H., R. Tomi, Y. Asada, and T. Furuya. 2002. Phytoremediation of bisphenol A by cultured suspension cells of Eucalyptus perriniana—regioselective hydroxylation and glycosylation. Tetrahedron Lett. 43:1603-1606. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirano, T., Y. Honda, T. Watanabe, and M. Kuwahara. 2000. Degradation of bisphenol A by the lignin-degrading enzyme, manganese peroxidase, produced by the white-rot basidiomycete, Pleurotus ostreatus. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 64:1958-1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hugo, N., J. Armengaud, J. Gaillard, K. N. Timmis, and Y. Jouanneau. 1998. A novel -2Fe-2S- ferredoxin from Pseudomonas putida mt2 promotes the reductive reactivation of catechol 2,3-dioxygenase. J. Biol. Chem. 273:9622-9629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hui Bon Hoa, G., C. Di Primo, I. Dondaine, S. G. Sligar, I. C. Gunsalus, and P. Douzou. 1989. Conformational changes of cytochromes P-450cam and P-450lin induced by high pressure. Biochemistry 28:651-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ike, M., C. S. Jin, and M. Fujita. 1995. Isolation and characterization of a novel bisphenol A-degrading bacterium, Pseudomonas paucimobilis strain FJ-4. Jpn. J. Water Treat. Biol. 31:203-212. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imai, Y., and R. Sato. 1967. Conversion of P-450 to P-420 by neutral salts and some other reagents. Eur. J. Biochem. 1:419-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung, Y. S., H. S. Gao-Sheridan, J. Christiansen, D. R. Dean, and B. K. Burgess. 1999. Purification and biophysical characterization of a new [2Fe-2S] ferredoxin from Azotobacter vinelandii, a putative [Fe-S] cluster assembly/repair protein. J. Biol. Chem. 274:32402-32410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kitazume, T., A. Tanaka, N. Takaya, A. Nakamura, S. Matsuyama, T. Suzuki, and H. Shoun. 2002. Kinetic analysis of hydroxylation of saturated fatty acids by recombinant P450foxy produced by an Escherichia coli expression system. Eur. J. Biochem. 269:2075-2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krishnan, A. V., P. Stathis, S. F. Permuth, L. Tokes, and D. Feldman. 1993. Bisphenol-A: an estrogenic substance is released from polycarbonate flasks during autoclaving. Endocrinology 132:2279-2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lambalot, R. H., D. E. Cane, J. J. Aparicio, and L. Katz. 1995. Overproduction and characterization of the erythromycin C-12 hydroxylase, EryK. Biochemistry 34:1858-1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis, D. F., and P. Hlavica. 2000. Interactions between redox partners in various cytochrome P450 systems: functional and structural aspects. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1460:353-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lobos, J. H., T. K. Leib, and T. M. Su. 1992. Biodegradation of bisphenol A and other bisphenols by a gram-negative aerobic bacterium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:1823-1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martinis, S. A., S. R. Blanke, L. P. Hager, S. G. Sligar, G. H. Hoa, J. J. Rux, and J. H. Dawson. 1996. Probing the heme iron coordination structure of pressure-induced cytochrome P420cam. Biochemistry 35:14530-14536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mo, H., S. S. Pochapsky, and T. C. Pochapsky. 1999. A model for the solution structure of oxidized terpredoxin, a Fe2S2 ferredoxin from Pseudomonas. Biochemistry 38:5666-5675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Munro, A. W., and J. G. Lindsay. 1996. Bacterial cytochromes P-450. Mol. Microbiol. 20:1115-1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakajima, N., Y. Ohshima, S. Serizawa, T. Kouda, J. S. Edmonds, F. Shiraishi, M. Aono, A. Kubo, M. Tamaoki, H. Saji, and M. Morita. 2002. Processing of bisphenol A by plant tissues: glucosylation by cultured BY-2 cells and glucosylation/translocation by plants of Nicotiana tabacum. Plant Cell Physiol. 43:1036-1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Keefe, D. P., K. J. Gibson, M. H. Emptage, R. Lenstra, J. A. Romesser, P. J. Litle, and C. A. Omer. 1991. Ferredoxins from two sulfonylurea herbicide monooxygenase systems in Streptomyces griseolus. Biochemistry 30:447-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olea, N., P. Pazos, and J. Exposito. 1998. Inadvertent exposure to xenoestrogens. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 7(Suppl. 1):S17-S23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Omura, T., and R. Sato. 1964. The carbon monoxide-binding pigment of liver microsomes. Evidence for its hemoprotein nature. J. Biol. Chem. 239:2370-2378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Omura, T., and R. Sato. 1964. The carbon monoxide-binding pigment of liver microsomes. Solubilization, purification, and properties. J. Biol. Chem. 239:2379-2387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peterson, J. A., J. Y. Lu, J. Geisselsoder, S. Graham-Lorence, C. Carmona, F. Witney, and M. C. Lorence. 1992. Cytochrome P-450terp. Isolation and purification of the protein and cloning and sequencing of its operon. J. Biol. Chem. 267:14193-14203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pottenger, L. H., J. Y. Domoradzki, D. A. Markham, S. C. Hansen, S. Z. Cagen, and J. M. Waechter, Jr. 2000. The relative bioavailability and metabolism of bisphenol A in rats is dependent upon the route of administration. Toxicol. Sci. 54:3-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pritchett, J. J., R. K. Kuester, and I. G. Sipes. 2002. Metabolism of bisphenol A in primary cultured hepatocytes from mice, rats, and humans. Drug Metab. Dispos. 30:1180-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramachandra, M., R. Seetharam, M. H. Emptage, and F. S. Sariaslani. 1991. Purification and characterization of a soybean flour-inducible ferredoxin reductase of Streptomyces griseus. J. Bacteriol. 173:7106-7112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ronen, Z., and A. Abeliovich. 2000. Anaerobic-aerobic process for microbial degradation of tetrabromobisphenol A. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2372-2377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakurai, A., S. Toyoda, and M. Sakakibara. 2001. Removal of bisphenol A by polymerization and precipitation method using Coprinus cinereus peroxidase. Biotechnol. Lett. 23:995-998. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sasaki, M., J. Maki, K. Oshiman, Y. Matsumura, and T. Tsuchido. 2005. Biodegradation of bisphenol A by cells and cell lysate from Sphingomonas sp. strain AO1. Biodegradation 16:449-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shimada, H., S. Nagano, H. Hori, and Y. Ishimura. 2001. Putidaredoxin-cytochrome P450cam interaction. J. Inorg. Biochem. 83:255-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sielaff, B., J. R. Andreesen, and T. Schrader. 2001. A cytochrome P450 and a ferredoxin isolated from Mycobacterium sp. strain HE5 after growth on morpholine. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 56:458-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spivack, J., T. K. Leib, and J. H. Lobos. 1994. Novel pathway for bacterial metabolism of bisphenol A. Rearrangements and stilbene cleavage in bisphenol A metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 269:7323-7329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Staples, C. A., P. B. Dorn, G. M. Klecka, S. T. O'Block, and L. R. Harris. 1998. A review of the environmental fate, effects, and exposures of bisphenol A. Chemosphere 36:2149-2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stern, J. O., and J. Peisach. 1974. A model compound study of the CO-adduct of cytochrome P-450. J. Biol. Chem. 249:7495-7498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strobel, H. W., and J. D. Dignam. 1978. Purification and properties of NADPH-cytochrome P-450 reductase. Methods Enzymol. 52:89-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sugita-Konishi, Y., S. Shimura, T. Nishikawa, F. Sunaga, H. Naito, and Y. Suzuki. 2003. Effect of bisphenol A on non-specific immunodefenses against non-pathogenic Escherichia coli. Toxicol. Lett. 136:217-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ta, D. T., and L. E. Vickery. 1992. Cloning, sequencing, and overexpression of a [2Fe-2S] ferredoxin gene from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 267:11120-11125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanaka, T., K. Yamada, T. Tonosaki, T. Konishi, H. Goto, and M. Taniguchi. 2000. Enzymatic degradation of alkylphenols, bisphenol A, synthetic estrogen and phthalic ester. Water Sci. Technol. 42:89-95. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsutsumi, Y., T. Haneda, and T. Nishida. 2001. Removal of estrogenic activities of bisphenol A and nonylphenol by oxidative enzymes from lignin-degrading basidiomycetes. Chemosphere 42:271-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uchida, H., T. Fukuda, H. Miyamoto, T. Kawabata, M. Suzuki, and T. Uwajima. 2001. Polymerization of bisphenol A by purified laccase from Trametes villosa. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 287:355-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wong, L. L. 1998. Cytochrome P450 monooxygenases. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2:263-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yim, S. H., H. J. Kim, and I. S. Lee. 2003. Microbial metabolism of the environmental estrogen bisphenol A. Arch. Pharm. Res. (Seoul) 26:805-808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu, C., and I. C. Gunsalus. 1974. Cytochrome P-450cam. II. Interconversion with P-420. J. Biol. Chem. 249:102-106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]