Abstract

Envoy, a PAS/LOV domain protein with similarity to the Neurospora light regulator Vivid, which has been cloned due to its lack of expression in a cellulase-negative mutant, links cellulase induction by cellulose to light signaling in Hypocrea jecorina. Despite their similarity, env1 could not compensate for the lack of vvd function. Besides the effect of light on sporulation, we observed a reduced growth rate in constant light. An env1PAS− mutant of H. jecorina grows significantly slower in the presence of light but remains unaffected in darkness compared to the wild-type strain QM9414. env1 rapidly responds to a light pulse, with this response being different upon growth on glucose or glycerol, and it encodes a regulator essential for H. jecorina light tolerance. The induction of cellulase transcription in H. jecorina by cellulose is enhanced by light in the wild-type strain QM9414 compared to that in constant darkness, whereas a delayed induction in light and only a transient up-regulation in constant darkness of cbh1 was observed in the env1PAS− mutant. However, light does not lead to cellulase expression in the absence of an inducer. We conclude that Envoy connects the light response to carbon source signaling and thus that light must be considered an additional external factor influencing gene expression analysis in this fungus.

The ascomycete Hypocrea jecorina (anamorph Trichoderma reesei) is a biotechnologically important fungus which is used for the production of cellulolytic and hemicellulolytic enzymes (8, 20, 21) and also has potential for the production of heterologous proteins driven by some of the cellulase promoters. Therefore, the regulation of cellulase gene transcription has been investigated in some detail for two cellulase genes (cbh1 and cbh2), and the involvement of at least three transcriptional activators (Ace1 [49], Ace2 [2], and the Hap2/3/5 complex [62]) and one repressor (Cre1) (29, 30) has been documented. However, the pathway signaling the presence of cellulose or cellulose-derived inducers has so far not been elucidated.

To identify genes potentially involved in this signaling process, we previously applied a rapid subtraction hybridization (RaSH) approach to study mRNAs induced for cellulase formation in the wild-type strain H. jecorina QM9414 and a mutant strain, H. jecorina QM9978, which is defective in the induction of cellulase gene expression (51). One of the genes identified thereby encoded a protein with high similarity to the Neurospora crassa light desensitization protein Vivid (see below), thus raising the question of the interrelationship between light and cellulase formation in H. jecorina. Light is known to stimulate asexual sporulation in Trichoderma viride, Trichoderma atroviride, and Trichoderma harzianum (7) but has not yet been reported to influence other metabolic or physiological activities in Trichoderma.

In N. crassa, a paradigm for light regulation processes and circadian rhythms (for a review, see reference 16), all of the known light-induced phenotypes are regulated by blue light (37), and all blue-light-induced phenotypes can be blocked by mutations in one of the two regulators, i.e., white collar 1 (wc-1) (5), which is in turn regulated by protein kinase C (3, 19), and white collar 2 (wc-2) (4; for an overview, see references 28 and 38). Recently, Schwerdtfeger et al. (55) showed that N. crassa has a dual light perception system that, besides white collar 1 and 2, also comprises the small PAS/LOV domain protein Vivid (25, 53), which is a member of the LOV domain subfamily of PER, ARNT, and SIM (PAS) domain proteins mediating both ligand binding and protein-protein interactions (59). Like many other PAS/LOV domains, Vivid is capable of binding a flavin chromophore (13, 55). It is localized in the cytoplasm and influences the transient phosphorylation of WC-1 (25, 53, 54).

For this study, we have cloned and functionally characterized the above-mentioned H. jecorina gene encoding a protein with a PAS/LOV domain which shows moderate similarity to Vivid. The objectives of this study were (i) to learn whether this gene is indeed also involved in a light response of H. jecorina, (ii) to learn how H. jecorina generally responds to light, and (iii) to learn whether this gene and light are indeed involved in cellulase gene expression by H. jecorina.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microbial strains and culture conditions.

H. jecorina (T. reesei) wild-type strain QM9414 (ATCC 26921) and the cellulase-negative mutant QM9978 (obtained from K. O' Donnell, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Peoria, IL) were used throughout this study. They were kept on malt agar and subcultured monthly. For Northern analysis, H. jecorina was grown in liquid culture in 1-liter Erlenmeyer flasks on a rotary shaker (250 rpm) at 28°C in 250 ml of Mandels-Andreotti minimal medium (41) supplemented with 0.1% peptone to induce germination and with a 1% (wt/vol) carbon source, using 108 conidia/liter (final concentration) as the inoculum.

Analyses of growth on plates and in Race tubes (43, 48) were carried out on 3% malt extract agar in daylight (light-dark [LD], 12-h-12-h cycles) or constant darkness.

N. crassa strain 74OR23-1A (FGSC 987) and the mutant strain vvdSS692 (FGSC 7852) were used for complementation studies. Vogel's minimal medium supplemented with 2% sucrose (14) was used for all Neurospora experiments. After 48 h of growth in darkness at 28°C, the mycelia were exposed to a 10-min light pulse of 25 μmol photons m−2 s−1, grown for an additional 60 min in the dark, and harvested after a second 10-min light pulse (54).

Escherichia coli JM109 (61) was used for the propagation of vector molecules and DNA manipulations. E. coli ER1647 (Novagen, Madison, Wis.) was used for plating, titrating, and screening the λBlueStar gene library. E. coli strain BM25.8 (Novagen) is lysogenic for λ phage and was used for automatic subcloning. Strains ER1647 and BM25.8 were grown at 37°C in Luria broth supplemented with 0.2% (wt/vol) maltose and 10 mM MgSO4 for the propagation of λ phage.

Analysis of biomass production in the presence of cellulose.

Mycelia were harvested after 96 h of growth in constant light or constant darkness on Mandels-Andreotti minimal medium (36) supplemented with 1% microcrystalline cellulose and were pelleted by centrifugation for 10 min at 14,000 × g. After the addition of 0.1 M NaOH, sonification for 3 min, incubation at room temperature for 3 h, and centrifugation, the protein content of the supernatant was measured by the Bradford method. Cultivations were done in triplicate.

Nucleic acid isolation and hybridization.

Strains were grown under the conditions specified in the legends in light (25 μmol photons m−2 s−1; 1,800 lx) or in constant darkness. Fungal mycelia were harvested by filtration, washed with tap water, frozen, and ground in liquid nitrogen. In cases of cultures grown in the dark, harvesting was done under a red safety light. Chromosomal DNA and total RNA were isolated and hybridized as described previously (51). Standard methods (50) were used for electrophoresis, blotting, and hybridization of nucleic acids. Densitometric scanning of autoradiograms was done using a Bio-Rad GS-800 calibrated densitometer for two independent cultivations and two expositions each. Measurements were normalized to 18S rRNA signals.

Screening of a chromosomal library of Hypocrea jecorina QM9414.

The isolation of chromosomal clones from a λBlueStar chromosomal library of Hypocrea jecorina QM9414 was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol (λBlueStar vector system; Novagen Inc., Madison, Wis.).

5′ and 3′ RACE.

For 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (5′ RACE), first-strand synthesis was performed with 3 μg total RNA, using a reverse transcription system (Promega, Madison, Wis.) at 42°C for 1 h according to the manufacturer's instructions, with a gene-specific primer (ENV1AR [5′ GAAGTGATGTCCGGAAGGATC 3′]). Single-stranded RNAs were digested with RNase A (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri), and afterwards the reaction mixture was purified using a QIAquick PCR cleanup kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). The DNA-RNA hybrid fragments were ligated into EcoRV-digested pBluescript, and PCR was performed with one nested gene-specific primer (ENV1BR21 [5′ GGGAAGTATGGTAACAACG 3′]) and one primer specific for pBluescript (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), using Q-Taq and Q-Solution (QIAGEN). As a control, chromosomal DNA was used to rule out that contamination of chromosomal DNA in the RNA preparations resulted in false-positive results.

For 3′ RACE, first-strand synthesis was performed using a reverse transcription system (Promega) at 42°C for 1 h according to the manufacturer's protocol, with the primer RACE-N [5′ GCGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCGAATTGGGTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT(AGC) 3′]. The reaction mixture was cleaned up using a QIAquick PCR cleanup kit (QIAGEN). PCR and nested PCR were performed according to standard protocols, using gene-specific primers and the primers RACE-N22 (5′ GCGTAATACGACTCACTATAGG 3′) and RASH18PB (5′ ACTATAGGGCGAATTGGG 3′), respectively.

Phylogenetic analysis.

Amino acid sequences were aligned with Clustal X 1.81 (60) and then visually adjusted. Phylogenetic analyses were performed in MEGA 2.1, using the minimum evolution (ME) approach. The reliability of nodes was estimated by minimum evolution bootstrap percentages (18) obtained after 500 pseudoreplications.

Transformation of N. crassa.

For complementation of the nonfunctional vvd mutant vvdSS692, the XhoI site within pBSXH (see below) was used for blunt-end ligation of a 4,244-bp Csp45I/DraI fragment spanning the whole cDNA and flanking sequences of the envoy gene into the vector after Klenow fill-in and dephosphorylation of both the fragment and the vector using calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (Promega), resulting in the complementation vector pENVHPH. The transformation of N. crassa conidia with pENVHPH was done as described previously (22). Transformants were made homokaryotic (17), and recombinants were identified by PCR.

Construction of H. jecorina env1PAS− strain and retransformation of this strain with the env1 wild-type gene.

To construct an env1PAS− strain of H. jecorina, part of the env1 coding region containing the PAS domain was deleted (Fig. 1). To this end, the pki1p::hph::cbh2t hygromycin resistance cassette present in pRLMEX30 (39) was released as an XhoI-HindIII fragment and cloned into the XhoI-HindIII sites of pBluescript SK(+) (Stratagene) to create pBSXH. A 1,077-bp fragment of the 5′ flanking sequence was PCR amplified using primers ENVDEL5F (5′-ATGGTACCGATGATGTCCAGCCTTC-3′ and ENVDEL5R (5′-ATCTCGAGTCGTAACTAGGCATAGAACTG-3′), digested with Acc65I and XhoI, and cloned into the Acc65I-XhoI sites of pBSXH. For the 3′ flanking sequence, a 1,005-bp fragment was amplified using primers ENVDEL3F (5′-AACCCGGGATAGATGCTAGGCGTACC-3′) and ENVDEL3R (5′-ACGGATCCGAGAAGATTGCATTCATTA-3′), digested with BamHI and SmaI, and cloned into the EcoRV-BamHI sites of pBSXH, which already contained the 5′ flanking sequence of env1, to obtain pDELENV. The deletion cassette was released from pDELENV by restriction digestion with Acc65I-BamHI, and 10 μg of the linear fragment was used for the transformation of protoplasts of the wild-type strain QM9414 as described previously (24). Transformants were selected on plates containing 50 μg/ml hygromycin B (Calbiochem, San Diego, California). Fungal DNAs were isolated from transformants by standard protocols and subjected to both Southern analysis and PCR, using primers ENVDEL5F and ENVDEL3R, to verify the replacement of the PAS domain of env1 in the genome. A Southern blot of SalI-digested chromosomal DNA of wild-type strain QM9414 env1PAS− was hybridized with a randomly labeled DNA fragment spanning the whole deletion cassette. The autoradiogram showed that the deletion was successful, and since no additional bands occurred (SalI sites are located outside the deletion cassette) in env1PAS− and the signal strength was similar to that of the wild type, that no ectopic integration had occurred. The PCR control confirmed the results of Southern blotting. No band indicating a wild-type background was detected.

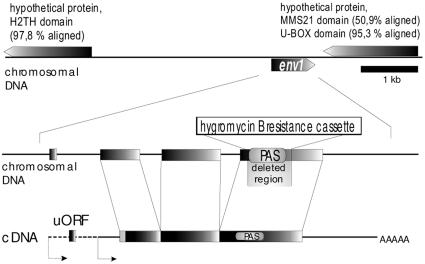

FIG. 1.

H. jecorina env1 locus and strategy for deletion of the PAS domain of env1 and complementation with env1. The location of env1 between genes encoding two hypothetical proteins (as predicted by a homology search within the Trichoderma draft genome database [http://gsphere.lanl.gov/trire1/trire1.home.html]) is shown. The transcription start points, as determined by RACE-PCR, are shown by arrows. The region deleted in env1PAS− is indicated, and the XbaI sites given show the region used for complementation of the mutant.

Complementation of env1PAS− with the env1 wild-type gene was achieved by cotransformation of an XbaI fragment comprising the entire gene and the amdS marker cassette (45a, 55a). Successful complementation was confirmed by Southern blotting as described above.

Complementation of the non-cellulase-inducible strain QM9978 with env1.

For complementation of QM9978, the above-mentioned plasmid pENVHPH was used, and the transformants were selected on plates containing hygromycin B as described above. Screening for integration of the complete env1 gene was done by Southern blotting.

RESULTS

envoy (env1), a gene differentially expressed between wild-type strain QM9414 and a cellulase-negative mutant, encodes a small PAS/LOV domain protein.

envoy was previously isolated by a RaSH approach (31) for identifying factors not induced by cellulose in a non-cellulase-inducible mutant strain. Thereby, three cDNA clones (cfa25C, cfa4B, and cfa90D) were isolated, which represented different fragments of the same gene. To obtain a full-length chromosomal clone, primers derived from cfa4B and cfa25C were designed and used to amplify a 496-bp PCR fragment, which was used as a probe for screening of a λBlueStar chromosomal library of H. jecorina QM9414. One positive clone was selected, and 4.5 kb of the clone was sequenced by primer walking. Because of its potential role in cellulose signaling, the gene was named envoy (env1; GenBank accession number AY551084) to indicate its potential function as a messenger.

RACE and reverse transcription-PCR analyses revealed two transcription start points, downstream of which two in-frame ATGs separated by 18 nucleotides are located. These two possible start codons would give rise to polypeptides of 207 and 201 amino acids (aa), with predicted molecular masses of 22.5 and 21.8 kDa and pIs of 5.83 and 5.50, respectively. An in-frame stop codon was also detected upstream of the two ATGs, indicating that RACE amplified the full-length cDNA (33).

The env1 gene is located on scaffold 30 in the Trichoderma reesei draft genome database v1.0 (http://gsphere.lanl.gov/trire1/trire1.home.html) and flanked by two as yet uncharacterized hypothetical proteins (Fig. 1). Both are putative DNA repair proteins, one of them comprising an MMS21 domain (COG5627) and a U box (smart00504) and one being a putative formamidopyrimidine-DNA glycosylase (H2TH domain; pfam06831; NCBI CCD search) (42).

The coding region of env1 is interrupted by two introns, of 80 and 89 bp, which were confirmed by sequencing of the respective cDNAs. Screening the sequence databases for the most similar proteins identified several hypothetical proteins from other filamentous fungi which display high degrees of similarity, for example, FG08456.1 (46% identity, 63% similarity, Gibberella zeae PH-1; accession number XP_388632), MG01041.4 (40% identity, 63% similarity, Magnaporthe grisea 70-15; accession number EAA49383), and AN3435.2 (46% identity, 62% similarity, Aspergillus nidulans FGSC A4; accession number EAA62912). The only characterized protein with significant similarity to Envoy was N. crassa Vivid (25). Envoy contains a PAS (Per, Arnt, and Sim) (59) and a LOV (light, oxygen, or voltage) domain (12, 13) and displays 38% identity and 57% similarity to Vivid over the whole aa sequence, but no significant similarity on the DNA level. Consistent with this, residues supposed to bind FMN and the conserved surface salt bridge (13) in N. crassa Vivid are also present in Envoy (Fig. 2A). In order to prove the presence of a flavin cofactor, we expressed env1 in E. coli as a glutathione S-transferase fusion protein, purified it, and scanned its absorbance between 300 and 500 nm. Interestingly, we did not detect any pigment that copurified with this protein during the purification procedure, and no absorbance maximum around 450 nm was detected (data not shown).

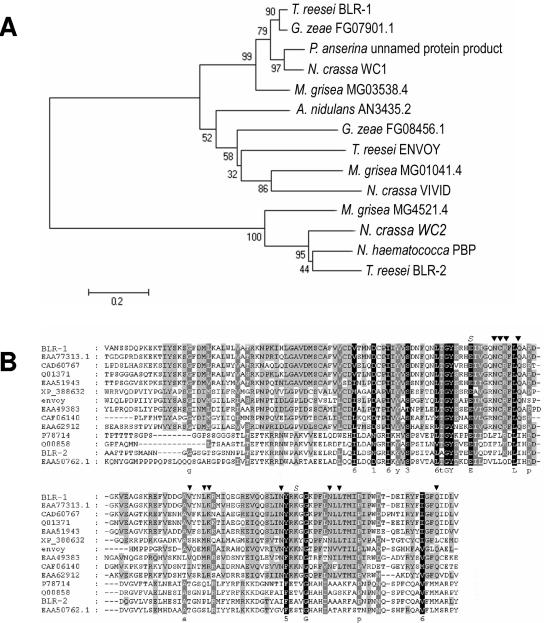

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree and multiple sequence alignment of PAS domain proteins. (A) Phylogenetic tree obtained by MEGA 2.1, using the minimum evolution method. The sequences used include all sequences present in the alignment in panel B. Numbers at branches indicate their bootstrap support values. (B) Multiple sequence alignment of PAS domain-containing proteins sharing similarity with env1. Residues similar to those interacting with the chromophore in the phy3 LOV2 crystal structure (13) are marked with an arrow, and residues that form the conserved salt bridge therein are marked with “S.” PAS/LOV sequences in the alignment include the following: Hypocrea jecorina blue light regulator 1 (BLR-1; accession no. AY823264), Gibberella zeae hypothetical protein FG07941.1 (EAA77313.1), unnamed Podospora anserina protein product (CAD60767.1), Neurospora crassa white collar 1 protein (WC-1; Q01371), Magnaporthe grisea hypothetical protein MG03538.4 (EAA51943), Gibberella zeae hypothetical protein FG08456.1 (XP_388632), Hypocrea jecorina Envoy (Env1; AY551084), Magnaporthe grisea hypothetical protein MG01041.4 (EAA49383), Neurospora crassa vivid PAS protein VVD (CAF06140), Aspergillus nidulans hypothetical protein AN3435.2 (EAA62912), Neurospora crassa white collar 2 (WC-2; P78714), Nectria hematococca cutinase gene palindrome binding protein (Q00858), Hypocrea jecorina blue light regulator 2 (BLR-2; AY823265), and Magnaporthe grisea hypothetical protein MG04521.4 (EAA50762.1).

Envoy and Vivid are members of a phylogenetic sister clade to the WC-1 photoreceptor proteins.

In view of the fact that env1 did not complement an N. crassa vvd mutant, we were interested in whether Envoy and Vivid are orthologues at all. To investigate this, we performed a minimum evolution analysis of the aa sequences of the PAS domains of Envoy, Vivid, and some other proteins of high similarity identified in the genome sequences of G. zeae, A. nidulans, and M. grisea (the best NCBI BLASTx hits for the respective organisms were chosen; GenBank accession numbers for these proteins and those mentioned below are given in the legend to Fig. 2A). In addition, the PAS domains of proteins from these five fungi which share similarity to Neurospora crassa WC-1 and WC-2 were also included in the analysis. The results show that WC-1/Vivid/Envoy orthologues and WC-2 orthologues form two strongly supported clusters wherein the WC-1 orthologues form a well-supported terminal clade, indicating that WC-1 and Vivid/Envoy arose from a common ancestor after splitting from WC-2 (Fig. 2B). However, in contrast to the clades containing WC-1 and WC-2 orthologues, the branch leading to the clade containing Vivid, Envoy, and their putative orthologues, and also the branches therein, received only poor bootstrap support, indicating that the proteins in this clade may have been subject to different evolutionary pressure.

envoy is unable to complement an N. crassa vvdSS692 mutant.

Because of the considerable similarity between H. jecorina env1 and N. crassa vvd, we reasoned that env1 could be an orthologue of vvd. We therefore examined whether env1 could compensate for a loss of function of vvd. To this end, we used the env1 structural gene, including its own promoter, and transformed it into N. crassa vvdSS692, which represents a null phenotype of vvd (25). However, transformants which had stably integrated the construct into the N. crassa chromosome showed no regain of the pale orange wild-type phenotype indicative of compensation for the lost vvd function by env1. To analyze this in more detail, we examined the transcription of the albino-1 (al-1) gene of N. crassa, which encodes a phytoene desaturase required for carotenogenesis and is strongly regulated by light (36). The experiment was based on the rationale that al-1 expression of Neurospora after a first light pulse is almost completely insensitive to a second light pulse, and incubation in the dark for 2 h is required to restore maximum competence for a new light response (3, 40, 53). In contrast, the mutant strain vvdSS692 already shows expression of al-1 after a second light pulse after 1 h of incubation in the dark (53). When env1+ transformants of N. crassa were subjected to two such subsequent light pulses with 1 h of darkness in between, they showed the anticipated increase in abundance of the env1 transcript (Fig. 3A), similar to that seen with vvd in the wild-type strain (25, 53). Hence, the UAR element(s) in the env1 promoter is recognized by N. crassa during light induction under similar conditions as those inducing vvd. However, after the second light pulse, the env1+ transformant essentially behaved like the vvdSS692 mutant (Fig. 3A), i.e., al-1 was clearly upregulated. This indicates that the transient light insensitivity of wild-type N. crassa, which is impaired in N. crassa vvdSS692, was not restored by env1. Consequently, env1 is unable to complement a nonfunctional vvd mutant of N. crassa.

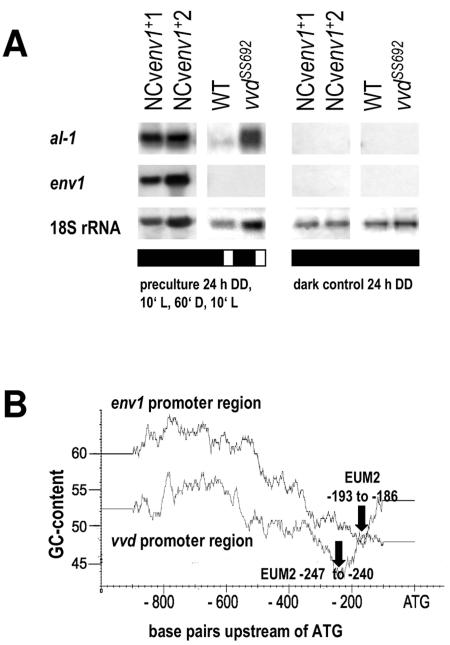

FIG. 3.

Hypocrea jecorina env1 does not complement a Neurospora crassa nonfunctional vvd mutant but shares two putative UASs with vvd. (A) Northern analysis of al-1 and env1 transcript accumulation in the Neurospora crassa wild-type strain 74OR23-1a (WT), in the vvd mutant strain vvdSS692, and in vvdSS692 mutant strains complemented with the original env1 gene, including its promoter and terminator, indicated by NCvenv1+1 and NCvenv1+2. After being precultured in the dark, the cultures were illuminated for 10 min, incubated in the dark for 1 h, and again subjected to a light pulse of 10 min. For controls, the cultivations were done in constant darkness. Twenty micrograms of RNA was loaded per lane, and hybridizations were performed with a 0.5-kb fragment of env1 spanning the region containing the PAS domain and with a 0.7-kb PCR fragment of al-1 from Neurospora crassa. Hybridization with an 18S rRNA probe is shown as a control. (B) Analysis of GC content within the promoter regions of env1 and vvd. One thousand nucleotides of the regions upstream of the respective start codon were screened, and the areas of low GC content were searched for shared motifs. Approximate positions of the identified shared UAS motif (5′ ACCTTGAC 3′; EUM2) in env1 and vvd are given schematically.

env1 and vvd share two as yet uncharacterized putative upstream activation sequences (UASs).

In silico analysis of the 5′ untranslated regions of env1 and vvd revealed two as yet uncharacterized nucleotide motifs (5′-CTGTGC-3′, called envoy upstream motif 1 (EUM1) [positions −150 to −145], and 5′-ACCTTGAC-3′, called EUM2 [positions −186 to −193]) which are conserved between H. jecorina and N. crassa and which could therefore be involved in the light response. This assumption is further supported by a concordant decrease of the GC content around both motifs in both promoters (Fig. 3B; the position of EUM2 is given for both promoters). Interestingly, a perfect consensus of the hexanucleotide of EUM1 was also found in the promoters of the two H. jecorina cellulase genes, cbh1 (−37, in reverse orientation) and cbh2 (−159), and the H. jecorina light regulator homologues blr1 (−375) and blr2 (−887, −553, and −772, in reverse orientation), suggesting that all of these genes may be under (partial) coregulation.

Env1 is essential for normal growth of H. jecorina in the presence of light.

The finding that env1 cannot complement N. crassa vvd does not rule out that it may nevertheless be involved in a light response of H. jecorina. Since the effect of light on the growth of H. jecorina is essentially unknown, we first tested this hypothesis. To this end, the Race tube system, which is frequently used with N. crassa, was adapted for use with H. jecorina (Fig. 4A). An analysis of the extension rate of the wild-type strain over 14 days in Race tubes in cycles of daylight and darkness (LD, 12-h-12-h cycles) and in constant darkness revealed a light-dependent sporulation banding pattern (Fig. 4B) and a reduced extension rate in daylight (Fig. 4C). Consistent with this result, an analysis of growth on microcrystalline cellulose in shake flask cultures also resulted in a 20% lower biomass density in the presence of light.

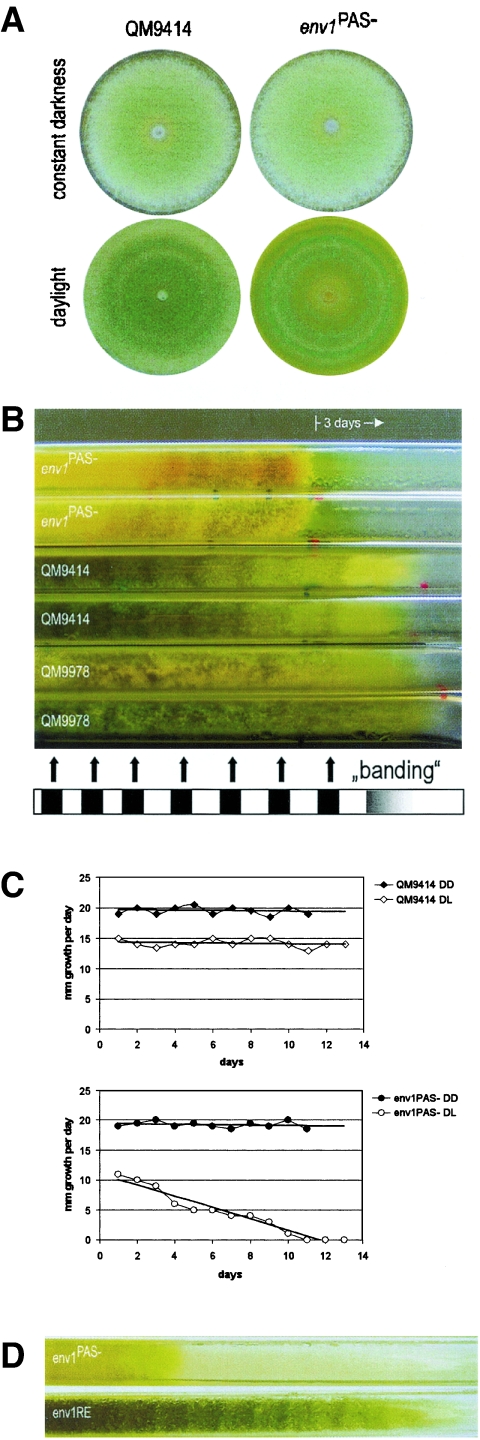

FIG. 4.

Growth and sporulation of Hypocrea jecorina QM9414 are influenced by light, and the light response is altered in the env1PAS− mutant. (A) QM9414 shows characteristic “banding” upon growth in daylight (LD, 12-h-12-h cycles; 25°C; malt extract medium). In contrast, the env1PAS− mutant exhibited only poor growth and a faint mycelium with a decreasing extension rate and completely stopped growing after 10 days, while the wild-type strain QM9414 grew constantly (as shown for three more days). The defect of the non-cellulaseinducible strain QM9978 seems to impact not only cellulase formation but also growth characteristics in daylight, as its extension rate is slightly higher and the banding pattern observed in the wild type is not detectable. (B) Growth and sporulation of env1PAS− are unaltered in constant darkness. In daylight (LD, 12-h-12-h cycles; 25°C; malt extract medium), env1PAS− shows secretion of a yellow pigment into the medium. (C) The wild-type strain QM9414 grows significantly slower in daylight than in constant darkness. While growing at approximately the same rate in constant darkness, env1PAS− exhibits a decreasing extension rate in daylight (measurements were taken from Race tubes, as described in the text). (D) Retransformation of env1PAS− with an XbaI fragment comprising the wild-type env1 gene, resulting in strain env1RE, reconstitutes the phenotype of the wild-type strain QM9414.

In order to learn whether env1 would be involved in this effect, we prepared an env1 mutant strain in which the PAS domain was replaced by the pki1p::hph::cbh2t marker cassette (Fig. 1) and analyzed whether such a mutant would show an altered response to light. Transformants which consequently lacked the native env1 gene were screened by Southern analysis and PCR, and one, env41E, was chosen for further investigations and named env1PAS−. The growth of env1PAS− on plates in constant darkness was indistinguishable from that of the wild type (Fig. 4B), but it grew much slower in daylight, forming only a faint mycelium, and sporulated poorly. Essentially consistent data were obtained using Race tubes. H. jecorina env1PAS− grew at the same rate as the parent strain QM9414 in constant darkness but showed a reduced and continuously decreasing extension rate in the presence of light until growth stopped completely after 10 days (Fig. 4A and C), while the wild-type stain continued growing at a constant extension rate (shown in Fig. 4A for three more days). Retransformation of env1PAS− with the wild-type env1 gene fully restored the wild-type phenotype (Fig. 4D). We concluded that in H. jecorina, a loss of function of env1 results in an inhibition of growth by light.

Light stimulates transcription of env1.

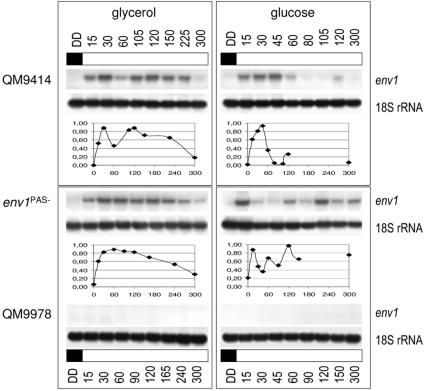

In order to learn whether the expression of env1 itself responds to light, we quantified the abundance of the env1 transcript during a shift of cultures of the wild-type strain QM9414 and the mutant strain env1PAS− from constant darkness to constant light (1,800 lx; 25 μmol photons m−2 s−1) on glucose and glycerol (Fig. 5). This experiment provided clear evidence that the transcription of env1 is stimulated by light, with its transcript being virtually undetectable during cultivation in the darkness. In addition, some characteristic fluctuations in the abundance of the env1 transcript were apparent, which also occurred in subsequent separate experiments. Interestingly, the env1PAS− mutant strain accumulated the truncated transcript in a different manner from that of the wild-type strains: glucose-grown cultures displayed a more pronounced oscillating increase in env1 mRNA abundance over time than did the wild type, whereas glycerol-grown cultures showed a broad, delayed peak of env1 mRNA accumulation after illumination, which slowly declined.

FIG. 5.

env1 responds to light, and this response is dependent on the carbon source. env1 is not transcribed during growth in Mandels-Andreotti minimal medium containing 1% (wt/vol) glucose or glycerol as the carbon source in constant darkness (DD) but is induced within 15 min after a shift to constant light (1,800 lx; 25 μmol photons m−2 s−1). The Northern data resulted from two sets of separate experiments which revealed complementary and consistent results. An α-32P-random-labeled PCR fragment spanning the region from the second transcription start point to the start of the region deleted in env1PAS− was used as a probe, and 20 μg of total RNA was loaded per lane. The results were quantified, and the amount of light-induced transcription of env1 in the specified strain was normalized to the 18S rRNA control hybridization. Graphs below the Northern blots show transcription levels above the background.

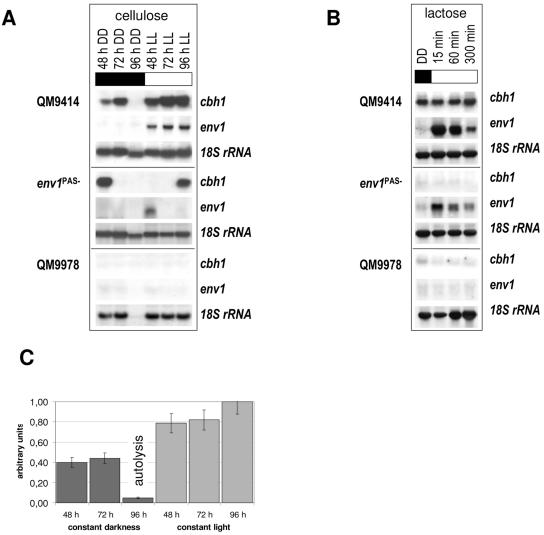

We also studied the accumulation of the env1 transcript during growth on the cellulase-inducing carbon sources cellulose and lactose (Fig. 6A and B). In the wild-type strain, env1 mRNA accumulation was only detectable for growth in constant light (cellulose) or after illumination (lactose). Interestingly, this regulation of env1 transcription was altered in the env1PAS− mutant grown on cellulose, as the truncated env1 transcript could only be detected after 48 h in the presence of light (Fig. 6A).

FIG. 6.

Cellulase expression is significantly influenced by light during growth on microcrystalline cellulose and is dependent on functional env1. (A) cbh1 is significantly more up-regulated in the wild-type strain QM9414 during cultivation in Mandels-Andreotti minimal medium supplemented with 1% microcrystalline cellulose as the carbon source in constant light (1,800 lx; 25 μmol photons m−2 s−1), indicated by LL, after 48, 72, and 96 h than in constant darkness (DD). For Northern blotting, 20 μg of total RNA was loaded per lane, and a 1.2-kb α-32P-radiolabeled PCR fragment of cbh1 was used as a probe. (B) Analysis of env1 light response and cbh1 transcription on lactose. Mycelia were precultured for 25 h in Mandels-Andreotti minimal medium with 1% (wt/vol) lactose as the carbon source, and then the cultures were exposed to light and harvested after the indicated times. Twenty micrograms of total RNA was loaded per lane, and a 1.2-kb α-32P-radiolabeled PCR fragment of cbh1 was used as a probe. (C) Quantitative analysis of cbh1 signal strength in the wild-type strain QM9414. The transcription of cbh1 after 48 or 72 h on microcrystalline cellulose is decreased roughly 50% in constant light compared to that in constant darkness. While transcription increases further from 72 to 96 h in constant light, autolysis starts in constant darkness, as indicated by sporulation and foaming of the culture and consequently a poor quality of total RNA. Measurements were combined from two independent cultivations; densitometric analysis was done for two expositions of the respective blots.

Cellulose degradation and cellulase gene expression are stimulated in H. jecorina by light.

The results described above suggest a role of env1 in light sensing by H. jecorina, consistent with its amino acid similarity to vvd. However, since env1 was cloned because of its lack of expression in a cellulase-negative mutant strain, we also surmised a role of env1 in cellulase induction. Consequently, we first investigated whether cellulase formation by H. jecorina would be light sensitive. To this end, the accumulation of the transcript of the major cellulase gene cbh1 (encoding cellobiohydrolase I) was studied in the wild-type strain QM9414 and the env1PAS− mutant during growth on microcrystalline cellulose in constant darkness and under constant illumination. Figure 6A shows that illumination resulted in a steady accumulation of cbh1 mRNA over 96 h of growth, which was significantly delayed in the env1PAS− mutant and only detectable at 96 h. In the wild type, cbh1 transcript accumulation was decreased to approximately 50% in the dark (Fig. 6C) and declined after 72 h, and the mRNA for cbh1 was virtually absent at 96 h. This is due to the fact that in constant darkness H. jecorina had already terminated growth and started to autolyze at 96 h. On the other hand, the mutant strain env1PAS− accumulated a high level of cbh1 mRNA after 48 h in constant darkness, but no transcript was detected afterwards at 72 and 96 h.

An analysis of cbh1 transcription was also performed with the soluble cellulase inducer lactose. When cultures of the wild-type strain, pregrown on lactose for 25 h in the dark, were subjected to illumination, cbh1 gene transcription occurred, whereas this transcription was blocked in the env1PAS− mutant and the non-cellulase-inducible mutant QM9978 (Fig. 6B).

The stimulatory effect of light was still dependent on the presence of an inducer, as demonstrated by the lack of accumulation of the cbh1 transcript during growth on glucose or glycerol after illumination. Also, upon growth with glycerol for 24 h in constant light, no cbh1 transcript was detected (data not shown).

Env1 is not expressed in the cellulase-negative mutant H. jecorina QM9978.

Consistent with the isolation of env1 by the RaSH approach, env1 is not transcribed in the cellulase-negative mutant strain QM9978, either under illumination or in the dark, independent of the carbon source (Fig. 5 and 6A and B). Interestingly, an analysis of the env1 promoter in the non-cellulase-inducible strain QM9978 revealed that EUM1 exhibits a point mutation in this strain, with a change from 5′ CTGTGC 3′ to 5′ CTGTAC 3′. In order to test whether this mutation might impair the transcription of env1, we transformed the mutant strain with the entire wild-type env1 gene, including >1 kb of its 5′ upstream sequences. One positive transformant, QM9978env1+8A, was selected. It was grown for 24 h in constant darkness on glycerol and then exposed for 30 min to light. However, no env1 transcript was detected under these conditions in QM9978env1+8A (data not shown), while the wild-type strain showed a strong increase in transcription of env1. In addition, this strain did not show the characteristic banding pattern of the wild-type strain QM9414 upon growth in daylight (Fig. 4B), and plate assays for examinations of cellulase formation revealed that this strain still did not express cellulases (data not shown). Therefore, the above-mentioned mutation is not the reason for the lack of env1 expression or cellulase inducibility; nevertheless, the defect of the mutant strain QM9978 in expressing cellulases and env1 is probably due to an impairment of the same, superior regulatory circuit.

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we have functionally characterized a gene (env1) which was cloned due to the fact that it is expressed under conditions of cellulase induction in H. jecorina and not expressed in a non-cellulase-inducible mutant (51). This gene encodes a small member of the PAS/LOV domain protein family. PAS/LOV domain proteins belong to the PAS superfamily, a class of sensory proteins named after Drosophila period (PER), vertebrate aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT), and Drosophila single-minded (47, 63). In addition to their sensory functions, PAS domains have been reported to mediate protein-protein interactions (59) and to bind various cofactors depending on their functional properties (12). So far, only one member of the family of small PAS/LOV domain proteins, the light response modulator Vivid of N. crassa, which is involved in photoadaptation and desensitization (25, 53, 55), has been described for eukaryotes. Because of the similarity between H. jecorina env1 and N. crassa vvd, we examined whether env1 would fulfill similar functions in H. jecorina as vvd does in N. crassa. However, env1, despite being efficiently transcribed under its own promoter in N. crassa, failed to complement the respective N. crassa mutant strain, indicating that Vivid may, at least in part, require different proteins for interaction than those required by Envoy. Moreover, nonfunctional vvd mutants do not show the light-sensitive phenotype observed with env1 (see below). Also, the recombinant Envoy protein, in contrast to the situation with Vivid (55), does not contain its cofactor, and the poorly resolved phylogenetic clades containing Envoy and Vivid all indicate differences between the two proteins which may eventually be of physiological significance. We concluded from all these findings that vvd and env1 are both involved in the regulation of light-dependent processes but may respond to different physiological stimuli which are typical for the different physiologies and habitats of these two fungi. Whereas N. crassa, with its heat-activated germination, is a rapid primary colonizer of newly available habitats arisen by, e.g., forest ignition, and shows abundant growth on the surface of its habitat (46), H. jecorina is a necrotrophic fungus which penetrates into the substrate and emerges to the surface only to sporulate (32). This difference is also reflected in the fact that vvd regulates carotenoid formation in response to different light conditions, whereas such a regulation is lacking in H. jecorina, which remains colorless (i.e., does not produce carotenoids or other pigments) when transferred to light.

Similar to N. crassa vvd, and consistent with its function in the light response, env1 also responds to the presence of light by a strong accumulation of its transcript. Interestingly, the kinetics of this accumulation differ with glucose and glycerol as carbon sources, and this effect was even more pronounced with the env1PAS− mutant (which produces a truncated transcript), thereby pointing toward an autoregulatory feedback loop which depends on the presence of the PAS domain. In this study, it became evident that the env1 transcript accumulates in an oscillating way upon a switch from constant darkness to constant light. Such oscillations typically arise from an interference in the half-time of mRNA decay and from the resulting time gap between transcription and translation, as shown for the zebra fish somitogenesis oscillator (35). These findings suggest that Envoy might be subject to a complex (auto)regulatory circuit, which warrants further detailed investigations.

In fungi, light is primarily known to influence sexual and asexual morphogenesis and sporulation (10, 11), but there are also reports about its influence on glucose uptake and metabolism (26, 27, 52). While this paper was in preparation, light was reported to inhibit the growth of N. crassa, Tuber borchii, and Trichoderma atroviride (1, 9). These findings are consistent with the presented evidence for a reduced growth rate of H. jecorina in the presence of light. The fact that N. crassa is also light sensitive is interesting, because the carotenoid pigment which it produces upon illumination is assumed to protect it from high light intensities (56). In T. atroviride, the inhibition by light was even stronger for a mutant with a mutation in the photoreceptor BLR-1, which is an orthologue of N. crassa WC-1 (9). This finding is consistent with the results from this study showing that light inhibition of H. jecorina is more severe in the H. jecorina env1PAS− mutant, thus indicating that photoreception and its modulation partially protect Hypocrea from the damaging effects of light. It is tempting to speculate that this is due to the regulation of induction of DNA photolyase, which has been shown to be up-regulated by light in T. atroviride (6). This light-dependent regulation could be fulfilled by the WC-1 and WC-2 orthologues BLR-1 and BLR-2 and by Envoy in Hypocrea jecorina.

The identification of env1 as a gene modulating cellulase gene expression in H. jecorina enabled us to detect that cellulase gene expression in this fungus is strongly influenced by light. Apart from the few reports mentioned above on the regulation of glucose uptake and metabolism by light, there is little known about the potential influence of light on nutrient assimilation in fungi. Here we showed that cellulase gene expression in H. jecorina is enhanced by light and that env1 is involved in the light-dependent regulation of cbh1 transcription. We have previously reported that cellulases are expressed on the conidia of H. jecorina (34), which is intriguing with respect to the fact that light stimulates conidiation in some Trichoderma spp., such as T. atroviride (23) and T. virens (44), and in H. jecorina (our unpublished data). Moreover, the H. jecorina cbh2 (encoding cellobiohydrolase II) promoter is able to trigger the expression of a bacterial reporter gene and to direct it to the conidial surface (57), demonstrating that the cbh2 promoter contains upstream acting sequences which respond to the signals triggering conidiation, including light. The influence of light on cellulase gene expression may therefore be derived from its coregulation with conidiation. It must be noted, however, that light alone is not sufficient to trigger cbh1 gene expression, because no cellulase transcript accumulated after exposure of mycelia to light in the absence of an inducer (data not shown). Also, light is not essential for cellulase gene expression, but only accelerates the rate of transcript accumulation (Fig. 6A and C), and therefore is only a gradual influence.

The fact that light stimulates cellulase gene expression raises the question of whether known light-dependent transcription factors may be involved. Indeed, binding sites for fungal GATA factors such as BLR-1 and BLR-2 are present in the promoters of cbh1 (positions −182, −188, −258, and −890), cbh2 (−714, in reverse orientation, and −838), and env1 (−417, in reverse orientation, and −753), which indicates that the regulation of cellulase expression as well as that of env1 could be driven by binding of the white collar complex to these promoters. However, we also identified two protein binding motifs, EUM1 and EUM2, in the promoters of env1/vvd, blr1, blr2, and the cellulase gene cbh1. The significance of these motifs with respect to cellulase gene expression and the light response warrants further investigation.

While the effect of light on cellulase formation in the wild-type strain is clearly shown and straightforward to interpret, the role of env1 in light-induced stimulation of cbh1 gene expression is apparently more complex. In the presence of light, the mutant strain env1PAS− shows a strongly retarded induction of cbh1, revealing that env1 and light both contribute significantly to the rate of cellulase gene expression. However, in constant darkness, the cbh1 transcript is seen during the early phase of cellulase induction. Thus, while contributing to the stimulation of cellulase induction upon illumination, Envoy apparently is also directly or indirectly responsible for maintenance of cbh1 gene expression in the darkness, and the PAS/LOV domain is required for this process. Crosson et al. (13) proposed a model that involves light-modulated changes in binding affinity between the LOV domain and its partner domain(s), in which the dynamic state of the LOV domain is the main determinant of its interactions with partner domains. Another PAS/LOV domain protein, the human Aryl hydrocarbon receptor AhR, binds several different ligands to regulate the expression of other genes in a ligand-dependent manner (15, 58). Besides binding of FMN (which is not likely according to an analysis of the ENV1-GST fusion protein), as suggested by the structure of Envoy (Fig. 2B), we assume a functionality comparable to that of AhR for Envoy by binding of several different ligands, thus responding to the presence of a certain carbon source in the medium.

The link between a universal and important physical environmental parameter such as light and the assimilation of a carbon compound such as cellulose suggests that cellulose degradation may play a major role in the physiology of this fungus. This finding may be of potential importance for the performance of industrial cellulase production as well as the production of heterologous proteins fused under the control of cellulase promoters (45). We also emphasize that the detection of an interconnection between light and cellulose assimilation may only be a first insight into a more global role of light on metabolism in Hypocrea and perhaps other fungi. Our data therefore place a general caveat on all previous investigations into this fungus, and eventually also on those with other fungi, where the condition of illumination has not been recorded or not been addressed. Differences in the results obtained by different research groups may eventually be due to differences in the illumination conditions during their investigations. The present study thus may trigger a search for light-dependent novel functions of several already characterized genes. In addition, our data offer the possibility of improving cellulase fermentations or recombinant protein production under the control of cellulase expression signals (45) by using illumination. While we have not yet optimized the conditions for maximal cellulase expression, a first enhancement in the rate of cellulase gene transcription was achieved by cultivation in constant light. It is thus conceivable that an optimized program of light pulses and darkness would further improve the process.

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Macino for collaboration in Neurospora transformation.

This work was supported by a grant from the Austrian Science Foundation (FWF-P17325) to C.P.K. Preliminary sequence data for blr-1 and blr-2 were obtained from The Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute (www.jgi.doe.gov) prior to publication of the genome sequence. The T. reesei genome sequencing project was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambra, R., B. Grimaldi, S. Zamboni, P. Filetici, G. Macino, and P. Ballario. 2004. Photomorphogenesis in the hypogeous fungus Tuber borchii: isolation and characterization of Tbwc-1, the homologue of the blue-light photoreceptor of Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet. Biol. 41:688-697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aro, N., A. Saloheimo, M. Ilmen, and M. Penttila. 2001. ACEII, a novel transcriptional activator involved in regulation of cellulase and xylanase genes of Trichoderma reesei. J. Biol. Chem. 276:24309-24314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arpaia, G., F. Cerri, S. Baima, and G. Macino. 1999. Involvement of protein kinase C in the response of Neurospora crassa to blue light. Mol. Gen. Genet. 262:314-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ballario, P., and G. Macino. 1997. White collar proteins: PASsing the light signal in Neurospora crassa. Trends Microbiol. 5:458-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ballario, P., P. Vittorioso, A. Magrelli, C. Talora, A. Cabibbo, and G. Macino. 1996. White collar-1, a central regulator of blue light responses in Neurospora, is a zinc finger protein. EMBO J. 15:1650-1657. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berrocal-Tito, G., L. Sametz-Baron, K. Eichenberg, B. A. Horwitz, and A. Herrera-Estrella. 1999. Rapid blue light regulation of a Trichoderma harzianum photolyase gene. J. Biol. Chem. 274:14288-14294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Betina, V., and V. Farkas. 1998. Sporulation and light-induced development in Trichoderma, p. 75-94. In C. P. Kubicek and G. E. Harman (ed.), Trichoderma and Gliocladium, vol. 1. Taylor & Francis, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchert, J., T. Oksanen, J. Pere, M. Siika-Aho, A. Suurnäkki, and L. Viikari. 1998. Applications of Trichoderma reesei enzymes in the pulp and paper industry, p. 343-363. In G. E. Harman and C. P. Kubicek (ed.), Trichoderma and Gliocladium, vol. 2. Taylor & Francis, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casas-Flores, S., M. Rios-Momberg, M. Bibbins, P. Ponce-Noyola, and A. Herrera-Estrella. 2004. BLR-1 and BLR-2, key regulatory elements of photoconidiation and mycelial growth in Trichoderma atroviride. Microbiology 150:3561-3569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charlile, M. J. 1965. The photobiology of fungi. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 16:175-201. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cole, G. T. 1986. Models of cell differentiation in conidial fungi. Microbiol. Rev. 50:95-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crosson, S., and K. Moffat. 2001. Structure of a flavin-binding plant photoreceptor domain: insights into light-mediated signal transduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:2995-3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crosson, S., S. Rajagopal, and K. Moffat. 2003. The LOV domain family: photoresponsive signaling modules coupled to diverse output domains. Biochemistry 42:2-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis, R. H., and F. deSerres. 1970. Genetic and microbial research techniques for Neurospora crassa. Methods Enzymol. 17A:79-143. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Denison, M. S., and S. R. Nagy. 2003. Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor by structurally diverse exogenous and endogenous chemicals. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 43:309-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunlap, J. C., and J. J. Loros. 2004. The Neurospora circadian system. J. Biol. Rhythms 19:414-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ebbole, D., and M. Sachs. 1990. A rapid and simple method for isolation of Neurospora crassa homokaryons using microconidia. Fungal Genet. News 1990:17-19. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Felsenstein, J. 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39:783-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Franchi, L., V. Fulci, and G. Macino. 2005. Protein kinase C modulates light responses in Neurospora by regulating the blue light photoreceptor WC-1. Mol. Microbiol. 56:334-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galante, Y., A. De Conti, and R. Monteverdi. 1998. Application of Trichoderma enzymes in the food and feed industries, p. 327-342. In G. E. Harman and C. P. Kubicek (ed.), Trichoderma and Gliocladium, vol. 2. Taylor & Francis, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galante, Y., A. De Conti, and R. Monteverdi. 1998. Application of Trichoderma enzymes in the textile industry, p. 311-325. In G. E. Harman and C. P. Kubicek (ed.), Trichoderma and Gliocladium, vol. 2. Taylor & Francis, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garceau, N. Y., Y. Liu, J. J. Loros, and J. C. Dunlap. 1997. Alternative initiation of translation and time-specific phosphorylation yield multiple forms of the essential clock protein Frequency. Cell 89:469-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gressel, J., and E. Galun. 1967. Morphogenesis in Trichoderma: photoinduction and RNA. Dev. Biol. 15:575-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gruber, F., J. Visser, C. P. Kubicek, and L. H. de Graaff. 1990. The development of a heterologous transformation system for the cellulolytic fungus Trichoderma reesei based on a pyrG-negative mutant strain. Curr. Genet. 18:71-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heintzen, C., J. J. Loros, and J. C. Dunlap. 2001. The PAS protein Vivid defines a clock-associated feedback loop that represses light input, modulates gating, and regulates clock resetting. Cell 104:453-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hill, E. P. 1976. Effect of light on growth and sporulation of Aspergillus ornatus. J. Gen. Microbiol. 95:39-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horenstein, E. A., and E. C. Cantino. 1964. An effect of light on glucose uptake by the fungus Blastocladiella britannica. J. Gen. Microbiol. 37:59-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Idnurm, A., and J. Heitman. 2005. Light controls growth and development via a conserved pathway in the fungal kingdom. PLoS Biol. 3:e95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ilmen, M., M. L. Onnela, S. Klemsdal, S. Keranen, and M. Penttila. 1996. Functional analysis of the cellobiohydrolase I promoter of the filamentous fungus Trichoderma reesei. Mol. Gen. Genet. 253:303-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ilmen, M., C. Thrane, and M. Penttila. 1996. The glucose repressor gene cre1 of Trichoderma: isolation and expression of a full-length and a truncated mutant form. Mol. Gen. Genet. 251:451-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang, H., D. C. Kang, D. Alexandre, and P. B. Fisher. 2000. RaSH, a rapid subtraction hybridization approach for identifying and cloning differentially expressed genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:12684-12689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klein, D., and D. E. Eveleigh. 1998. Ecology of Trichoderma, p. 57-74. In C. P. Kubicek and G. E. Harman (ed.), Trichoderma and Gliocladium, vol. 1. Taylor & Francis, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kozak, M. 1996. Interpreting cDNA sequences: some insights from studies on translation. Mamm. Genome 7:563-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kubicek, C. P., G. Mühlbauer, M. Grotz, E. John, and E. M. Kubicek-Pranz. 1988. Properties of the conidial-bound cellulase system of Trichoderma reesei. J. Gen. Microbiol. 134:1215-1222. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewis, J. 2003. Autoinhibition with transcriptional delay: a simple mechanism for the zebrafish somitogenesis oscillator. Curr. Biol. 13:1398-1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li, C., and T. J. Schmidhauser. 1995. Developmental and photoregulation of al-1 and al-2, structural genes for two enzymes essential for carotenoid biosynthesis in Neurospora. Dev. Biol. 169:90-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Linden, H., M. Rodriguez-Franco, and G. Macino. 1997. Mutants of Neurospora crassa defective in regulation of blue light perception. Mol. Gen. Genet. 254:111-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu, Y., Q. He, and P. Cheng. 2003. Photoreception in Neurospora: a tale of two white collar proteins. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 60:2131-2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mach, R. L., M. Schindler, and C. P. Kubicek. 1994. Transformation of Trichoderma reesei based on hygromycin B resistance using homologous expression signals. Curr. Genet. 25:567-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Macino, G., S. Baima, A. Carattoli, G. Morelli, and E. M. Valle. 1993. Blue light regulated expression of geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase (albino-1) gene in Neurospora crassa, p. 117-124. In B. Maresca, G. S. Kobayashi, and H. Yamaguchi (ed.), Molecular biology and its application to medical mycology, vol. H69. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mandels, M., and R. Andreotti. 1978. Problems and challenges in the cellulose to cellulase fermentation. Proc. Biochem. 13:6-13. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marchler-Bauer, A., J. B. Anderson, C. DeWeese-Scott, N. D. Fedorova, L. Y. Geer, S. He, D. I. Hurwitz, J. D. Jackson, A. R. Jacobs, C. J. Lanczycki, C. A. Liebert, C. Liu, T. Madej, G. H. Marchler, R. Mazumder, A. N. Nikolskaya, A. R. Panchenko, B. S. Rao, B. A. Shoemaker, V. Simonyan, J. S. Song, P. A. Thiessen, S. Vasudevan, Y. Wang, R. A. Yamashita, J. J. Yin, and S. H. Bryant. 2003. CDD: a curated Entrez database of conserved domain alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:383-387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Merrow, M., T. Roenneberg, G. Macino, and L. Franchi. 2001. A fungus among us: the Neurospora crassa circadian system. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 12:279-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mukherjee, P. K., J. Latha, R. Hadar, and B. A. Horwitz. 2003. TmkA, a mitogen-activated protein kinase of Trichoderma virens, is involved in biocontrol properties and repression of conidiation in the dark. Eukaryot. Cell 2:446-455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Penttila, M. E. 1998. Heterologous protein production in Trichoderma, p. 365-382. In G. E. Harman and C. P. Kubicek (ed.), Trichoderma and Gliocladium, vol. 2. Taylor & Francis, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 45a.Penttila, M., H. Nevalainen, M. Ratto, E. Salminen, and J. Knowles. 1987. A versatile transformation system for the cellulolytic filamentous fungus Trichoderma reesei. Gene 61:155-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perkins, D. D. 1992. Neurospora: the organism behind the molecular revolution. Genetics 130:687-701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ponting, C. P., and L. Aravind. 1997. PAS: a multifunctional domain family comes to light. Curr. Biol. 7:R674-R677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ryan, F. J., G. W. Beadle, and E. L. Tatum. 1943. The tube method of measuring the growth rate of Neurospora. Am. J. Bot. 30:784-799. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saloheimo, A., N. Aro, M. Ilmen, and M. Penttila. 2000. Isolation of the ace1 gene encoding a Cys(2)-His(2) transcription factor involved in regulation of activity of the cellulase promoter cbh1 of Trichoderma reesei. J. Biol. Chem. 275:5817-5825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 51.Schmoll, M., S. Zeilinger, R. L. Mach, and C. P. Kubicek. 2004. Cloning of genes expressed early during cellulase induction in Hypocrea jecorina by a rapid subtraction hybridization approach. Fungal Genet. Biol. 41:877-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schreckenbach, T., B. Walckhoff, and C. Verfuerth. 1981. Blue-light receptor in a white mutant of Physarum polycephalum mediates inhibition of spherulation and regulation of glucose metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 78:1009-1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schwerdtfeger, C., and H. Linden. 2001. Blue light adaptation and desensitization of light signal transduction in Neurospora crassa. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1080-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schwerdtfeger, C., and H. Linden. 2000. Localization and light-dependent phosphorylation of white collar 1 and 2, the two central components of blue light signaling in Neurospora crassa. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:414-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schwerdtfeger, C., and H. Linden. 2003. Vivid is a flavoprotein and serves as a fungal blue light photoreceptor for photoadaptation. EMBO J. 22:4846-4855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55a.Seiboth, B., S. Hakola, R. L. Mack, P. L. Suominen, and C. P. Kubicek. 1997. Role of four major cellulases in triggering of cellulase gene expression by cellulose in Trichoderma reesei. J. Bacteriol. 179:5318-5320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stahl, W., and H. Sies. 2003. Antioxidant activity of carotenoids. Mol. Aspects Med. 24:345-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stangl, H., F. Gruber, and C. P. Kubicek. 1993. Characterization of the Trichoderma reesei cbh2 promoter. Curr. Genet. 23:115-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Swanson, H. I. 2002. DNA binding and protein interactions of the AHR/ARNT heterodimer that facilitate gene activation. Chem. Biol. Interact. 141:63-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Taylor, B. L., and I. B. Zhulin. 1999. PAS domains: internal sensors of oxygen, redox potential, and light. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63:479-506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thompson, J. D., T. J. Gibson, F. Plewniak, F. Jeanmougin, and D. G. Higgins. 1997. The CLUSTAL_X Windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:4876-4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zeilinger, S., A. Ebner, T. Marosits, R. Mach, and C. P. Kubicek. 2001. The Hypocrea jecorina HAP 2/3/5 protein complex binds to the inverted CCAAT-box (ATTGG) within the cbh2 (cellobiohydrolase II-gene) activating element. Mol. Genet. Genomics 266:56-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhulin, I. B., B. L. Taylor, and R. Dixon. 1997. PAS domain S-boxes in Archaea, Bacteria and sensors for oxygen and redox. Trends Biochem. Sci. 22:331-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]