Abstract

Rotavirus NSP4 is a multifunctional endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-resident nonstructural protein with the N terminus anchored in the ER and about 131 amino acids (aa) of the C-terminal tail (CT) oriented in the cytoplasm. Previous studies showed a peptide spanning aa 114 to 135 to induce diarrhea in newborn mouse pups with the 50% diarrheal dose approximately 100-fold higher than that for the full-length protein, suggesting a role for other regions in the protein in potentiating its diarrhea-inducing ability. In this report, employing a large number of methods and deletion and amino acid substitution mutants, we provide evidence for the cooperation between the extreme C terminus and a putative amphipathic α-helix located between aa 73 and 85 (AAH73-85) at the N terminus of ΔN72, a mutant that lacked the N-terminal 72 aa of nonstructural protein 4 (NSP4) from Hg18 and SA11. Cooperation between the two termini appears to generate a unique conformational state, specifically recognized by thioflavin T, that promoted efficient multimerization of the oligomer into high-molecular-mass soluble complexes and dramatically enhanced resistance against trypsin digestion, enterotoxin activity of the diarrhea-inducing region (DIR), and double-layered particle-binding activity of the protein. Mutations in either the C terminus, AAH73-85, or the DIR resulted in severely compromised biological functions, suggesting that the properties of NSP4 are subject to modulation by a single and/or overlapping highly sensitive conformational domain that appears to encompass the entire CT. Our results provide for the first time, in the absence of a three-dimensional structure, a unique conformation-dependent mechanism for understanding the NSP4-mediated pleiotropic properties including virus virulence and morphogenesis.

Rotavirus is the most common cause of life-threatening, severe dehydrating diarrhea in children and animals (50). Rotavirus infection can be either symptomatic or asymptomatic. But the genetic/molecular basis for rotavirus virulence is not yet clearly understood. The recent identification of the nonstructural protein 4 (NSP4) as the first viral enterotoxin has attracted considerable attention toward understanding its structure and function. But analysis of NSP4 sequences from more than 175 strains failed to reveal any sequence motifs or amino acids that segregated with the virulence phenotype of the virus. Furthermore, a peptide spanning amino acids (aa) 114 to 135 was reported to induce diarrhea at an approximately 100-fold molar excess compared to the full-length protein (6). This suggested that other regions in the protein might influence its diarrhea-inducing potential. Also, the extreme C terminus, including the terminal methionine, was shown to be important for double-layered particle (DLP)-binding activity. NSP4 is 175 aa in length, with the N-terminal region anchored in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and approximately 131 aa of the C terminus oriented in the cytoplasm. The C-terminal tail (CT) appears to exhibit all the known biological properties of the protein (18). Attempts to crystallize the CT were so far not successful, which could be attributed to the highly unstructured/flexible nature of the region about 40 aa from the C terminus (57). To date, only the structure of a synthetic peptide corresponding to the highly conserved region spanning aa 95 to 134 that formed a tetrameric coiled coil was determined (10). However, the coiled-coil domain lacks the information necessary to predict a structural basis for rotavirus virulence, as a peptide from this region exhibited highly reduced diarrhea-inducing potential compared to the full-length protein (6). It is therefore of interest to evaluate the influence of the N- and C-terminal regions on the biochemical and biophysical properties of the CT, which could provide insights into the structural features that might play a critical role in modulating its biological functions and thus probably the virus virulence.

Rotaviruses are nonenveloped, icosahedral, triple-layered particles, the outer layer made of viral spike protein 4 (VP4) and VP7, the intermediate layer consisting of the subgroup antigen VP6, and the inner layer composed of VP2 (18, 47). The genome consists of 11 segments of double-stranded RNA that code for six structural and six nonstructural proteins (18).

NSP4, encoded by genome segment 10, is an ER-resident glycoprotein. The primary translational product of 20 kDa becomes a polypeptide of 28 kDa upon glycosylation in the ER. An uncleaved signal sequence precedes the three hydrophobic domains H1, H2, and H3 at the amino-terminal region of the protein (Fig. 1A). While most of the H1 domain (aa 17 to 21), which contains two N-linked high-mannose glycosylation sites, resides in the luminal side of the ER, H2 (aa 28 to 47) traverses the ER lipid bilayer and functions both as a signal and as a membrane anchor sequence. The H3 region (aa 67 to 85), embedded on the surface of the cytoplasmic side of the ER membrane, alone appears to mediate association of the protein with membrane (7, 12, 18). Recently, the sequence between aa 85 and 123 was also shown to be involved in ER retention of the protein (36). From the ER, the protein emerges in the cytoplasm near aa 44 and thus, about 131 residues contribute to the cytoplasmic tail (7, 12).

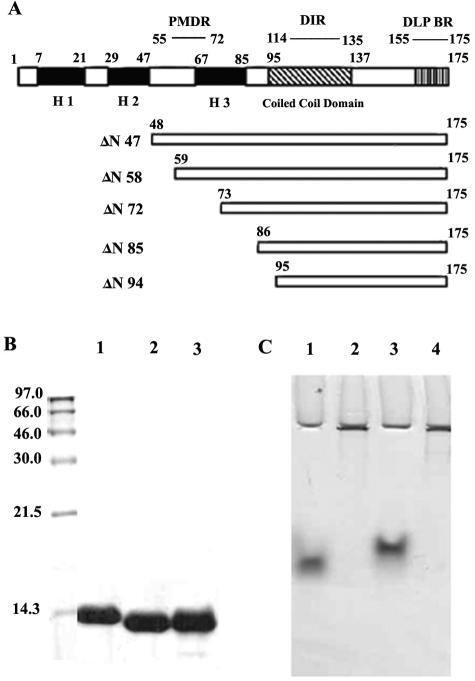

FIG. 1.

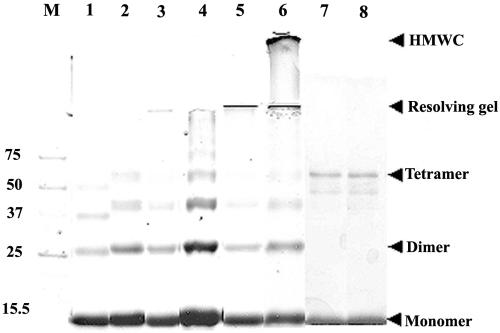

(A) Schematic representation of deletion mutants ΔN47, ΔN57, ΔN72, ΔN85, and ΔN94 of NSP4 from rotavirus strain Hg18. PMDR, proximal membrane-destabilizing region; DLP-BR, double-layered particle-binding region. Darkly shaded boxes represent the three N-terminal hydrophobic domains H1, H2, and H3. (B) SDS-PAGE in 16% gel of the purified NSP4ΔN72, NSP4ΔN85, and NSP4ΔN94 mutant proteins. Molecular weights of the markers are indicated to the left of the gel. (C) Native PAGE of NSP4ΔN72, NSP4ΔN85, and NSP4ΔN94 from strains Hg18 and SA11 in an 8% gel. Lane 1, Hg18ΔN94; lane 2, Hg18ΔN72; lane 3, Hg18ΔN85; lane 4, SA11ΔN72. Note that ΔN72 from both the strains remained near the wells.

A distinctive feature of rotavirus morphogenesis in MA104 cells is that the DLPs assembled in the cytoplasm bud into the lumen of the ER, where the virus undergoes maturation by addition of the outer capsid. During budding into the lumen of the ER, the DLP becomes ephemerally enveloped in a membrane vesicle. The exact mechanism or the order of outer capsid assembly and removal of the transient envelope from the mature virion has yet to be understood. The mature virions are released into the lumen of the ER (18). NSP4 plays a central role in rotavirus morphogenesis by functioning as the ER-resident receptor for the immature DLPs, and about 20 aa from the extreme C terminus, including the C-terminal methionine of the protein, appear to be important for DLP-binding activity (4, 5, 35, 45, 56-58). Recently, an alternate pathway of VP4 assembly into the virion involving membrane microdomains in the final maturation of the virus in polarized CaCo-2 cells has been proposed (15).

Crystal structure analysis of a synthetic peptide corresponding to aa 95 to 137 revealed that the region from aa 95 to 134 formed an α-helical homotetrameric coiled coil (10). Previous studies also observed NSP4 in dimeric and tetrameric forms as well as high-molecular-mass complexes (34, 58). The region between residues 48 and 91 (11) that includes the predicted amphipathic α-helical region between aa 55 and 72 (44), as well as the region from aa 114 to 135 (59), was reported to possess plasma membrane destabilization/permeabilization and cytopathic properties. The region spanning aa 112 to 140 contains overlapping binding sites for calcium and VP4 (5, 18). The region between aa 136 and 150 appears to form an antigenic site that is widely conserved among a variety of rotaviruses (8). NSP4 also occurs in oligomeric complexes with the outer capsid proteins VP4 and VP7 in enveloped particles (34). The interaction of NSP4 with calnexin and removal of the transient transmembrane envelope from the budding virus particles in the ER appear to require glycosylation of NSP4 as well as the outer capsid protein VP7 (33, 37, 53). NSP4 was also reported to inhibit the microtubule-mediated secretory pathway (64) and to alter cytoskeleton organization in polarized epithelial cells (55, 64).

NSP4 has been identified as the viral enterotoxin based on the observation that the protein caused diarrhea when administered intraperitoneally or intraileally in infant mice in an age-dependent manner (6, 24). The enterotoxigenic property of NSP4 has been proposed to be mediated by its interaction with an as yet unidentified cellular receptor in the gut epithelium, triggering a phospholipase C-mediated increase in intracellular Ca2+, which leads to enhanced Cl− secretion, reduced glucose and water absorption, and induction of secretory diarrhea (6, 17). A peptide spanning aa 114 to 135 has been shown to cause mobilization of Ca2+ from the ER and also induced diarrhea in mouse pups (6). A cleavage product of NSP4 representing aa 112 to 175 was reported to be secreted from infected cells as well as from cells transfected with a construct expressing this region and to cause intracellular Ca2+ increase and diarrhea in neonatal mice (66). An interspecies variable domain (ISVD) between residues 135 and 141 appears to influence the NSP4-mediated pathogenecity, and mutations in the ISVD, particularly aa 131, 135, and 138, were implicated in the attenuation or abrogation of cytotoxicity and diarrhea-inducing ability of the protein, as well as virus virulence in vivo (29, 38, 39, 65). But, in other studies, no such correlation was observed between virulent and attenuated human, feline, and murine strains (3, 13, 46, 62) that could be due to the possibility that virus attenuation can occur by several mechanisms, including mutations in other viral proteins (29, 42, 46, 62). Furthermore, there appears to be a lack of correlation between the virulence property of different viruses and the diarrheagenic property of cognate NSP4s in the heterologous mouse model (41, 46) and purified NSP4s from different strains of the same host species or different species showed significant variation in the 50% diarrheal dose (DD50) (6, 24, 41, 46, 62). Several factors such as virus strain, virus dose, and host factors appear to contribute to the wide variation observed in virulence (6, 25, 41, 42, 48, 62). It has been proposed that in natural infection, rotavirus virulence could be due to the cumulative effect of interactive properties of some or all of the viral proteins (62). Recently, the region between aa 87 and 145 of NSP4 was shown to interact with the extracellular matrix proteins laminin-β3 and fibronectin, signifying a new mechanism by which rotavirus disease may be established (9).

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the influence of the N- and C-terminal regions, as well as the interspecies variable domain from aa 135 to 146, which is implicated in virus virulence, of the CT on its biochemical, biophysical, and biological properties. Employing a variety of methods involving size exclusion chromatography, mass spectrometry, ultracentrifugation, far UV circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy, thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence assay, cross-linking, and electron microscopy, the influence of N- and C-terminal regions and the diarrhea-inducing region (DIR), including the ISVD, on biochemical and biophysical properties of the CT was investigated. The relative resistance against trypsin digestion and diarrhea-inducing capacity in a newborn mouse model system as well as the DLP-binding activity of the mutant proteins were assessed. Our results provide evidence, for the first time, for cooperation between a putative amphipathic α-helix at the N terminus and the DLP-binding region of the C terminus. This cooperation effected a unique conformational state in the oligomer that promoted stabilization of the coiled-coil region and multimerization of the CT. Mutations in either of the terminal regions or the DIR appeared to alter this unique conformational state, resulting in severely compromised biological properties of the protein. These results provide significant insights toward understanding the possible structural basis of rotavirus NSP4 in virus virulence and morphogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses and cells.

MA104 cells were grown as monolayers in M199 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (HyClone). Confluent cells were infected with the simian rotavirus strain SA11 or the new bovine G15 serotype strain Hg18 (49). Virus was grown for 3 days in M199 medium without serum in the presence of 0.1 μg/ml of trypsin. The supernatant from freeze-thawed infected cells was used for RNA extraction and DLP preparation.

Enzymes, reagents, and oligonucleotides.

Enzymes and other reagents were purchased from either Promega Biotech, Roche Applied Science, Invitrogen, or Amersham Biosciences. Oligonucleotide primers were designed in such a way as to be able to amplify the gene fragment from several rotavirus strains and were purchased from either Microsynth (Switzerland), Bioserve Technologies (Hyderabad, India), Sigma Aldrich (Bangalore, India), or MWG Biotech (Bangalore, India). Mouse anti-histidine (His) horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody was obtained from QIAGEN.

cDNA cloning of gene 10 and generation of NSP4 mutants in the modified expression vector pET22-NH.

Extraction of viral genomic RNA, cDNA synthesis, PCR amplification of the rotaviral genes, and cloning of the EcoRI- and HindIII-digested PCR fragments into pBluescript KS+ were carried out according to standard techniques and have been described previously (26). PCR fragments containing desired deletions or amino acid substitutions were generated using appropriate primers. Deletion or amino acid substitution in each mutant is described in Table 1. pET22(b+) was modified for the expression of proteins in fusion with an N-terminal His tag but without any residues derived from the vector. The His tag was preceded by methionine and aspartic acid at the N terminus. ΔN72 PCR fragment containing the His tag at the N terminus was inserted between the NcoI and HindIII sites of pET33(b+). The XbaI-HindIII fragment from this plasmid was inserted between the same sites in pET22(b+), thus generating pET22NHΔN72. Other mutants were generated by replacing the NdeI-HindIII fragment in pET22NHΔN72 with inserts corresponding to the desired mutations (Table 1). A single amino acid substitution mutant of the ISVD in the DIR from SA11, referred to as SA11 dirm4 (T139S), was generated by amplification of the ΔN72 region in two parts from aa 73 to 138 and aa 139 to 175 using appropriate primers. The upstream NdeI-SpeI and downstream SpeI-HindIII fragments were coinserted between NdeI and HindIII sites in pET22-NH. The SpeI site at the junction of the two fragments generated a T139S substitution that is common to all of the four DIR mutants (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Description of various deletion and amino acid substitution mutants of NSP4

| Mutant | Mutation at:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| N terminus | DIR | C terminus | |

| N-terminal deletion | |||

| ΔN47 | Lacks 47 aa | Wild type | Wild type |

| ΔN57 | Lacks 57 aa | Wild type | Wild type |

| ΔN72 | Lacks 72 aa | Wild type | Wild type |

| ΔN85 | Lacks 85 aa | Wild type | Wild type |

| ΔN94 | Lacks 94 aa | Wild type | Wild type |

| Deletion in ΔN72 AAH73-85 | |||

| ΔN77 | Lacks aa 73-77 | Wild type | Wild type |

| ΔN80 | Lacks aa 73-80 | Wild type | Wild type |

| ΔN83 | Lacks aa 73-83 | Wild type | Wild type |

| C-terminal mutants of ΔN72 | |||

| Hgm6 | As in ΔN72 | Wild type | 5-aa deletion |

| Hgm15 (M175I) | As in ΔN72 | Wild type | Met to Val |

| Amino acid substitutions in ΔN72 AAH73-85 | |||

| Hgm 1 | 6-aa substitution (I75A-F76S-N77D-T78A-L79S-L80A) | Wild type | Wild type |

| Hgm 3 | (F76S) | Wild type | Wild type |

| Mutations in ΔN72 DIR | |||

| SA11-dirm1 | As in ΔN72 | (T139S-G140A) | Wild type |

| SA11-dirm2 | As in ΔN72 | (Y131S-T139S) | Wild type |

| SA11-dirm3 | As in ΔN72 | (Y131S-T139S-G140A) | Wild type |

| SA11-dirm4 | As in ΔN72 | (T139S) | Wild type |

Expression, purification, and analysis of N- and C-terminal mutant NSP4s.

All the proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) by induction with 500 μM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) for 3 h. The cells were lysed by sonication in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, the lysate was adjusted to 100 mM in NaCl, and the debris was removed by centrifugation at 16,000 rpm. The supernatant was passed through an Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (QIAGEN) column; washed with a buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, supplemented with 100 mM NaCl and 40 mM imidazole; and eluted from the resin in the same buffer containing 500 mM imidazole. The proteins were dialyzed against a buffer consisting of 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and 100 mM NaCl with or without 1 mM CaCl2 or against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). For glutaraldehyde cross-linking, the oligomeric forms of the mutants were purified by fractionation on a Sephacryl S-200 column. Homogeneity of the purified protein was monitored by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (29) and mass spectrometry. The approximate molecular masses of the native proteins were determined by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) using a Sephacryl S-200 or S-300 column that was calibrated with bovine serum albumin (67 kDa), ovalbumin (45 kDa), chymotrypsinogen (25 kDa), and RNase A (13.7 kDa) as the standards (Amersham Biosciences). Void volume of the column was determined using blue dextran (>2,000 kDa). For molecular mass determination, 3 ml of protein solution, filtered through a 0.2-μm filter, was fractionated at a concentration of 2 mg/ml on a HiPrep 26/60 Sephacryl S-200 high-resolution column (Amersham Biosciences) using the Bio-Rad Biologic high-resolution chromatography system. The level of protein in each fraction in the peak was further monitored by SDS-PAGE (30), and the total amount of protein in each peak was estimated using Bradford protein assay reagent (Bio-Rad) after pooling all the fractions in the peak.

Glycerol gradient centrifugation.

One milligram of protein in 1 ml of 10% glycerol was layered on the top of linear 20 to 50% gradients of glycerol in a buffer containing 100 mM NaCl and 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, and centrifuged using an SW65 rotor for 3 h at 50,000 rpm at 4°C in a Beckman L8-80 M ultracentrifuge. Ferritin, catalase, bovine serum albumin, and purified glutathione S-transferase were used as controls to monitor the relative positions of the proteins in the gradient. Fractions (250 μl) were collected from the top of the gradient, and an equal volume from alternate fractions was analyzed in Tricine-SDS-polyacrylamide gels (52).

Mass spectrometry.

The mass spectra for the purified proteins and trypsin-digested products were determined using the matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization process (28). The molecular masses were determined in an Ultraflex time of flight/time of flight mass spectrometer from Bruker Daltonics. The protein samples, after precipitation with 9 volumes of ethanol at −20°C overnight, were dissolved in water and used for mass spectrometry.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy.

Far UV-CD spectra were recorded on a JASCO J-715 spectropolarimeter at protein concentrations ranging from 1 μM to 10 μM in 5 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 5 mM NaCl by using a 0.1-cm path length quartz cell. The molar residue ellipticity (θ)MRE was calculated using the formula [θ] = (θ)deg·MRW/10·l·c., where (θ)deg is ellipticity measured in degrees, MRW is the mean residue molecular mass, c is the protein concentration in g/liter, and l is the path length of the cell in cm. For thermal denaturation studies, CD signal at 222 nm was monitored using a thermostatted 1-cm path length quartz cell with a ramping rate of 60°/h at a concentration of 10 μM in 5 mM sodium phosphate buffer. Percent α-helical, β-strand, and random conformation contents were determined using the k2d program (2) and by the method of Greenfield and Fasman (22). Concentration of the proteins for CD experiments was calculated employing a standard formula using the absorbance at 280 nm in the presence of 8 M urea, as follows: concentration of protein (mg/ml) = A280 × dilution factor × molecular weight/molecular extinction coefficient. The molecular extinction coefficient of each mutant protein was calculated using the PeptideSort program of the Wisconsin package 10.3, Accelrys Inc., San Diego, CA.

ThT fluorescence assay.

ThT-binding assays were performed by combining 50 μl of 60 μM protein solution in 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.6, and 100 mM NaCl with 450 μl solution containing 10 μM ThT in a Shimadzu RF-5301 PC spectrofluorometer at 25°C. The excitation wavelength was 440 nm, and the emission was monitored from 450 to 600 nm (19, 43).

Chemical cross-linking.

Chemical cross-linking of the proteins was carried out using glutaraldehyde at protein to the cross-linker ratio of 1:1 to 1:200 for 5 min to 4 h, depending on the concentration of the cross-linker. At the end of the reaction, the unreacted cross-linker was quenched using 200 mM glycine (57). The protein was precipitated with trichloroacetic acid as described previously (57). The cross-linked proteins were analyzed by Tricine-SDS-PAGE (52).

Structure modeling of the amphipathic helix.

The NSP4 peptide sequence from aa 73 to 85 (VTIFNTLLKLAGY) of the G15 strain Hg18 was used to search for related sequences in the GenBank database and the Protein Data Bank by using the BLAST program (1). α-Helical model building for the NSP4 sequence was done using the molecular graphics program FRODO (27) based on the α-helical structures of the aligned sequences. A helical wheel program (23) has been used to represent and examine the nature of the model.

Trypsin digestion of NSP4 mutant proteins.

Aliquots of 10 μg each of the NSP4 mutant proteins dialyzed against 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl, and 2 mM CaCl2 were incubated with 0.1 μg of sequencing grade trypsin (Promega) in a 20-μl reaction. Proteolysis was carried out at 0°C, room temperature (RT), or 37°C for 0 to 2 h, and the reaction was terminated by the addition of 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The trypsin-cleaved products were analyzed by Tricine-SDS-PAGE (52). Molecular weights of the cleaved products were determined using mass spectrometry.

Assessment of diarrhea-inducing ability of NSP4.

Five- to seven-day-old BALB/c mouse pups were administered 50 μl of the protein sample in PBS intraperitoneally. Control animals received the same volume of either sterile PBS, rotavirus NSP5, or the C-terminal 164-aa-long fragment of NSP3 expressed and purified similar to the other proteins. Diarrhea was monitored from 30 min to 4 h postinjection. Diarrhea was noted and scored from 1 to 4 as described previously (6).

DLP-binding assay.

DLPs were prepared from SA11-infected MA104 cells using a previously described method (4). The trichlorofluoroethane-extracted virus sample was treated with 10 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, for 1 h at 37°C, and the DLPs were banded in cesium chloride gradients at 100,000 × g for 20 h at 4°C in a Beckman SW41 rotor (4). The DLPs were suspended in Tris-buffered saline, and the purity was analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The concentration of the DLPs was calculated using the following formula: concentration = optical density at 280 nm ×dilution factor × 0.2 mg/ml. Varying amounts of the purified NSP4 mutant proteins in 100 μl of PBS were adsorbed to wells. DLPs were added at 0.25 μg per well, and the amount bound was detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using anti-VP6 monoclonal antibody as described previously (4). The color developed after the addition of p-nitrophenyl phosphate was measured at 405 nm in Molecular Devices Spectramax 340c.

RESULTS

Analysis of the purified N-terminal deletion mutants of NSP4.

All the mutant proteins used in this study were soluble when expressed in E. coli. Initially, three mutants of NSP4 containing the His tag at the N terminus after dialysis, represented as ΔN72, ΔN85, and ΔN94 (Fig. 1A), were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1B). ΔN47 could not be expressed in E. coli and hence was not considered further in this study. Because of the low-level expression and association with membrane fraction, ΔN57 could not be purified in sufficient quantities and was used primarily in animal experiments. The level of expression of the proteins increased, with the extent of deletion from the N terminus, being ΔN94 ≥ ΔN85 > ΔN72 > ΔN57. The expected molecular masses, including the His tag, of 13.35 kDa (ΔN72), 12.00 kDa (ΔN85), and 10.95 kDa (ΔN94) were confirmed by mass spectrometry (data not shown) and SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1B). A surprising observation was that when the proteins were analyzed in 8.0% native polyacrylamide gels, ΔN72 from strains Hg18 and SA11 barely migrated down the wells compared to ΔN85 and ΔN94, which exhibited high electrophoretic mobility (Fig. 1C). The migration pattern of ΔN57 was identical to that of ΔN72 (data not shown). The pI values for both ΔN85 and ΔN72 were very similar, being 5.13 and 5.26, respectively. This anomalous mobility of ΔN72 was not due to the formation of insoluble complexes, as the protein was highly soluble and the protein filtered through a 0.2-μm filter or after ultracentrifugation at 50,000 rpm for 3 h exhibited similar property. The mobility differences are probably due to the ability of ΔN72 to form multimeric structures that could not enter the 8.0% native polyacrylamide gel. As both ΔN57 and ΔN72 showed similar properties in native gels, only ΔN72 was used in further experiments.

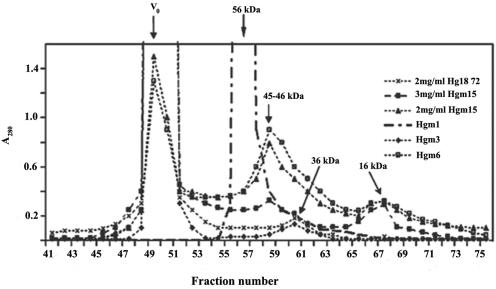

That ΔN72 from SA11 and Hg18 formed structures significantly larger than tetramers was confirmed by SEC of the protein at 3, 2, 1, or 0.5 mg/ml after filtration through a 0.2-μm filter. While both ΔN85 and ΔN94 eluted as single peaks with apparent molecular masses of 58 and 54 kDa, respectively (data not shown), ΔN72 showed a major peak in the void volume and a minor peak corresponding to approximately 36 kDa (Fig. 2). The amount of protein in the two peaks was in the ratio of approximately 95:5. No multimers of ΔN85 and ΔN94 were detected even after concentration to 20 mg/ml. The observed sizes of 58 and 54 kDa for ΔN85 and ΔN94 were greater than those expected for a tetramer, which probably reflects a relatively open conformation of the C terminus of the protein, as suggested previously (57), in contrast to the globular nature of the standard proteins. The fact that the majority of ΔN72 was excluded from the Sephacryl S-300 matrix suggests that it existed in multimeric forms of at least 8.0 MDa in size. Formation of high-molecular-weight complexes (HMWC) by ΔN72 was further confirmed by analysis of glycerol gradient fractions of the proteins by native PAGE in which the majority of ΔN72 was recovered from fractions toward the bottom of the gradient while the other two mutants were recovered from upper fractions. In contrast to ΔN72 from different fractions, all the control proteins were resolved in the native gel (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Analysis of NSP4 mutants ΔN72, Hgm1, Hgm3, Hgm6, and Hgm15 by size exclusion chromatography on a Sephacryl S-200 column as described in Materials and Methods. Note that the lower portion of the chromatograph has been enlarged to show the smaller peaks corresponding to the oligomers of ΔN72 and monomers of Hgm15 and Hgm6 and that absorbance units are arbitrary. Only a few fractions before the peak in the void volume are plotted. Fraction volume is 2 ml. V0, void volume. Arrows indicate positions of different peaks.

NSP4 aa 73 to 85 promote the multimerization and formation of higher-order structures.

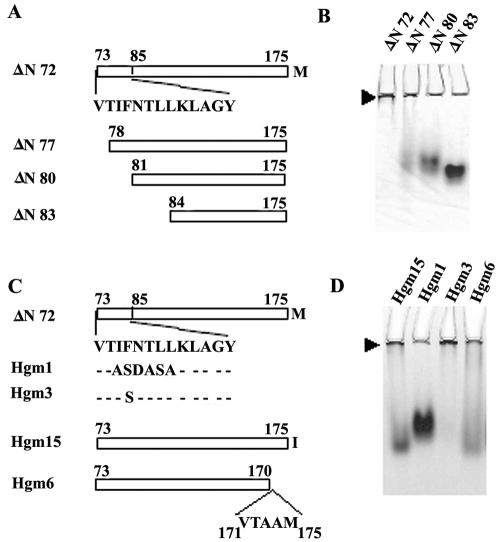

Since the region that is not common between ΔN72 and ΔN85 is the 13-residue peptide spanning aa 73 to 85 at the N terminus of ΔN72, fine deletions were made within this region (Fig. 3A) to determine if this region is indeed necessary for the formation of higher-order complexes. As shown in Fig. 3B, deletion of aa 73 to 77 resulted in the partial loss of the ability to form HMWC and deletion up to aa 80 or 83 resulted in the disappearance of the complex near the wells with concomitant appearance of the faster-migrating species. The faster-moving species of ΔN77 and ΔN80 exhibited a streak, with the former being more diffuse, while the mutant ΔN83 migrated as a compact band, suggesting that the former mutants formed intermediate-size complexes or complexes that were unstable under the electrophoretic conditions and that ΔN83 behaved like ΔN85. The pattern did not change with time of storage of the proteins, suggesting an equilibrium between the multimeric and oligomeric forms of different mutant proteins. These results indicated that the region from aa 73 to 85 promoted multimerization of the CT, leading to the formation of high-molecular-mass structures.

FIG. 3.

The region from aa 73 to 85 is necessary for multimerization of ΔN72. (A) Schematic representation of the deletion mutants Hg18 ΔN77, ΔN80, and ΔN83 of ΔN72 and the corresponding sequence of the region from residues 73 to 85. (B) Analysis by native PAGE, in an 8% gel, of the purified deletion mutant proteins. Arrowhead indicates HMWC below the wells. (C) Schematic representation of the amino acid substitution mutants of the region spanning aa 73 to 85 and the C-terminal mutants. The wild-type and mutant sequences of the region from aa 73 to 85 in Hg18ΔN72 mutants are indicated. (D) Native PAGE analysis of the N- and C-terminal mutants. Protein in each lane is indicated above the wells.

To identify the amino acid(s) between positions 73 and 85 that is critical for multimerization, we generated 2 amino acid substitution mutants (Table 1 and Fig. 3C). At amino acid position 76, different strains exhibited conservative amino acid substitutions, being either Phe, Leu, or Ile. As shown in Fig. 2, Hgm3 showed an elution pattern similar to that of ΔN72, with a major peak in the void volume corresponding to multimers and a minor peak corresponding to a species of an apparent molecular mass of 36 kDa (Fig. 2). In contrast, Hgm1, in which six consecutive amino acids from positions 75 to 80 were substituted (Table 1), showed a total loss of multimerization and only a single peak corresponding to an oligomer of an apparent molecular mass of 56 kDa was observed (Fig. 2). The multimeric/oligomeric nature of these mutants was further confirmed by native PAGE (Fig. 3D) and by centrifugation in glycerol gradients (data not shown).

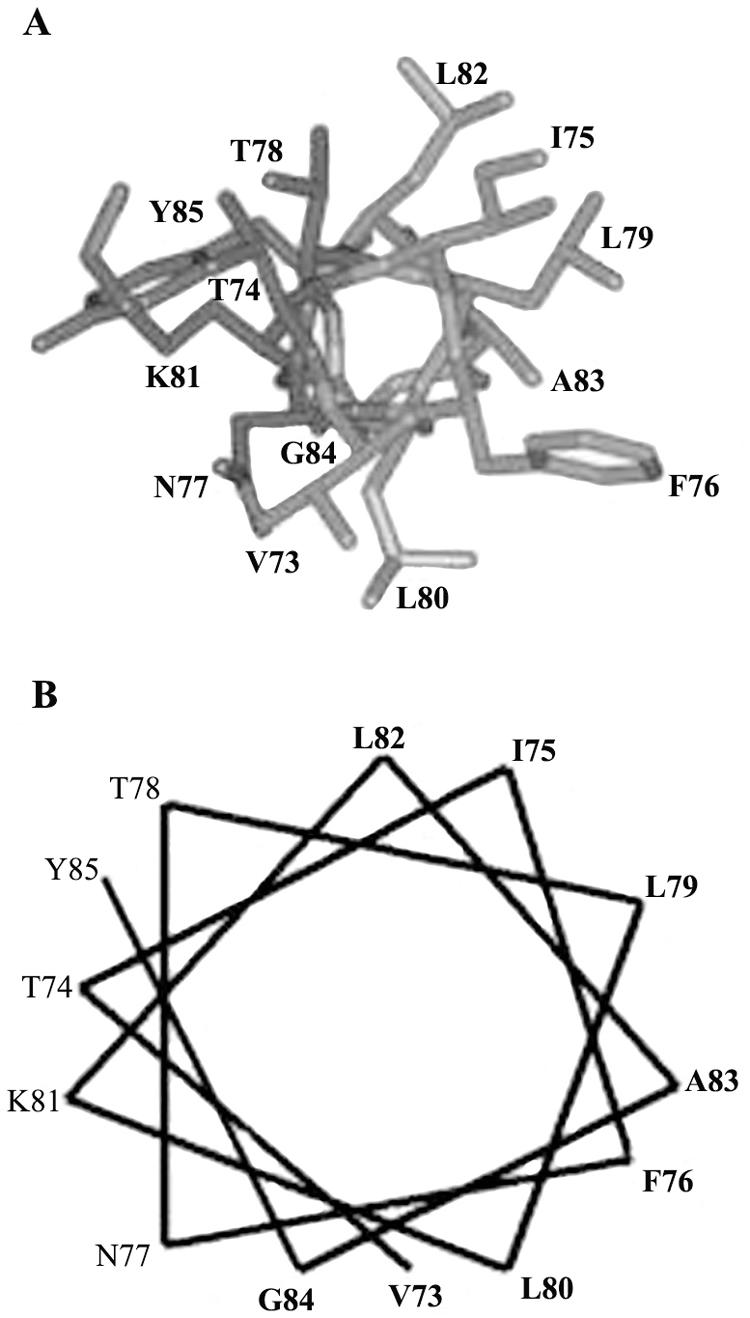

The region from residues 73 to 85 is predicted to assume an amphipathic α-helical conformation.

The above results indicated that the region spanning aa 73 to 85 promotes multimerization of the CT. Search for sequences similar to the 13-aa peptide sequence from Hg18 NSP4 in the GenBank database and Protein Data Bank revealed that several proteins that are dimeric, oligomeric, multimeric, or membrane associated (dehydrogenases, reductases, oxygenases, and many others) contained motifs that are similar to those in the NSP4 peptide sequence (data not shown). Structure modeling of the NSP4 peptide sequence VTIFNTLLKLAGY, based on the helical structures of the related peptide segments from human immunodeficiency virus integrase (20), cytochrome c oxidase (54), FtsA (60), and annexin I (63), revealed that rotavirus NSP4 peptide folded as an amphipathic α-helix, with one side being completely hydrophobic and the other side being completely hydrophilic (Fig. 4A). The dominant amphipathic nature of the helix was also evident from the helical wheel representation (Fig. 4B). This amphipathic α-helix from aa 73 to 85 will hereafter be referred to as AAH73-85.

FIG. 4.

NSP4 aa 73 to 85 are predicted to assume amphipathic α-helical conformation. (A) α-Helical model building of the Hg18 NSP4 peptide sequence (VTIFNTLLKLAGY) from residues 73 to 85 based on the α-helical structures of the aligned peptide segments from human immunodeficiency virus integrase, cytochrome c oxidase, FtsA, and annexin I. (B) Helical wheel representation of amino acid residues 73 to 85 from Hg18 NSP4 as an amphipathic helix. Note the clustering polar amino acids and a single lysine on one face and nonpolar amino acids on the other side of the putative helix.

Influence of the extreme C-terminal region on multimerization of ΔN72.

About 20 aa from the C terminus of the CT were shown to be involved in binding DLP, and the terminal methionine was observed to be important for this activity (56, 58). To assess the influence of the terminal methionine and the extreme C-terminal region on multimerization, purified mutant proteins Hgm15 (M175I) and Hgm6 (ΔN72ΔC5) (Table 1 and Fig. 3C) were fractionated by SEC. Surprisingly, when analyzed at a 2-mg/ml concentration, besides the multimeric form, both mutants showed significant amounts (50 to 70%) of an oligomeric form of an apparent molecular mass of 46 kDa (Fig. 2) that was further confirmed by native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Fig. 3D). The loss in multimerization ability/instability of the multimers of the methionine mutant Hgm15 was further evident when the mutant was subjected to centrifugation in glycerol gradients (data not shown). These mutants also exhibited a minor peak corresponding to an apparent molecular mass of 16 kDa (Fig. 2) that might represent a monomer. As evident from the chromatographic profiles, the equilibrium between the multimer, oligomer, and monomer of the C-terminal mutants is dependent on concentration. Increase in concentration of Hgm15 to 3 mg/ml profoundly shifted the equilibrium toward multimerization (Fig. 2). In contrast, the level of the 36-kDa species of ΔN72 was extremely low at any given concentration. The fact that a significant amount of monomer was seen for both the C-terminal mutants, but not for N-terminal mutants, suggests that an intact C terminus is needed for efficient oligomerization as well as multimerization of the tetramer and/or stabilization of the multimeric forms.

Influence of mutations in the DIR on multimerization of ΔN72.

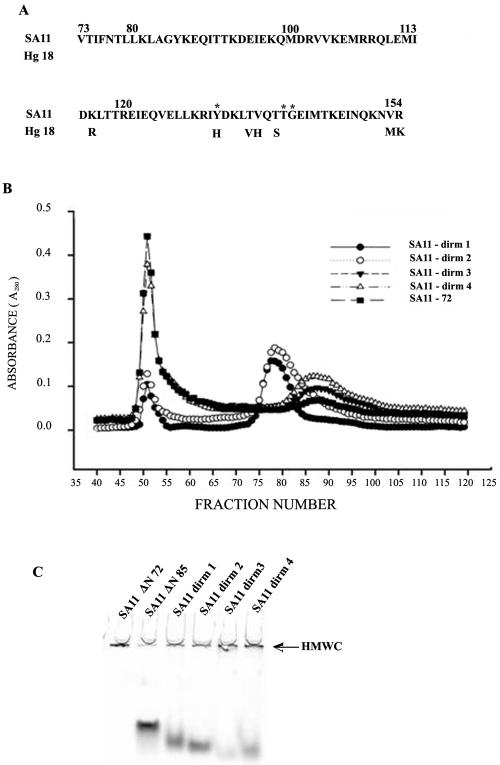

The region between aa 135 and 141 exhibited interspecies variation, and mutations in the ISVD of NSP4 (65) as well as at position 131 in a synthetic peptide from aa 114 to 135 in the DIR have been reported to affect the diarrhea-inducing ability of the protein (6). Since these mutations were thought to affect the conformation of the DIR (6, 65), single-, double-, and triple-amino acid mutants of SA11ΔN72 (dirm4, dirm1 and dirm2, and dirm3, respectively) (Table 1 and Fig. 5A) were generated and the influence of the mutations on multimerization was examined. As shown in Fig. 5B, >84% of dirm1 and dirm2 existed as oligomers of an apparent molecular weight of 53, suggesting that their multimerization ability or the stability of the multimers was severely affected. In contrast, while dirm3, in spite of having a triple-amino acid substitution, was very similar to ΔN72 in multimerization, only about 60% of the single conservative amino acid substitution mutant dirm4 existed in multimeric form, as observed by SEC. Furthermore, the second peak of dirm3 and dirm4 corresponded to an apparent molecular weight of 39 that closely corresponded with the minor peak exhibited by ΔN72 and Hgm3 (Fig. 5B). The relative proportion of multimeric and oligomeric forms of these mutants as observed by SEC was also confirmed by ultracentrifugation in glycerol gradients (data not shown) and native PAGE (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, unlike the C-terminal mutants, the ratio between the multimeric and oligomeric forms of the DIR mutants did not significantly change with concentration of the protein.

FIG. 5.

Influence of mutations in the DIR on multimerization. (A) Amino acid sequence of the DIR resistant to trypsin cleavage from SA11 and Hg18. Only those residues of NSP4 from Hg18 that are different from SA11 are shown. The positions of amino acid substitution in the DIR mutants are indicated by *. (B) Size exclusion chromatography of the SA11ΔN72 DIR mutants dirm1, dirm2, dirm3, and dirm4 in comparison with SA11ΔN72 on a Sephacryl S-200 column. Note that while dirm1 and dirm2 existed predominantly in oligomeric form of an apparent molecular weight of 53, dirm3 and dirm4 existed mainly in multimeric form. Arrows indicate peaks corresponding to the indicated molecular weights. (C) Native PAGE of the DIR mutant proteins. Arrow indicates HMWC near the wells.

Chemical cross-linking of NSP4 mutants.

Different mutants upon fractionation by SEC showed oligomeric forms with apparent molecular weights that were different from each other. To examine the quaternary state of the different mutants as well as to demonstrate that the formation of HMWC proceeded through multimerization of the tetramers, we subjected the multimeric as well as the purified oligomeric forms of some of the mutants to cross-linking using glutaraldehyde and the products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. As shown in Fig. 6, at an equimolar ratio of protein to cross-linker, tetramers of ΔN85 (lane 1) and ΔN72 (lane 4), as well as a range of multimeric forms of ΔN72, were observed by 60 min of cross-linking (lane 4). Increase in time of cross-linking (lanes 5 and 6) or the amount of the cross-linker (data not shown) resulted in the formation of HMWC that did not enter the gel. Significantly, HMWC of ΔN72 were generally seen only after tetramers were detectable, suggesting that the majority of the multimers are formed through the ordered aggregation of tetramers. As expected, ΔN85 and Hgm1 did not form multimers. Similarly, the apparent oligomeric forms of all the mutants of ΔN72, when cross-linked at low concentration (4 μg/ml) using an equimolar amount of the cross-linker, showed tetramers as expected from crystallographic studies of the DIR (10, 14) (unpublished results) but formed multimers, except Hgm1, at a high cross-linker concentration (data not shown). It is likely that the peaks corresponding to apparent molecular weight in the range of 36,000 to 39,000, which is significantly less than that expected for a tetramer, arise due to nonspecific adsorption of the protein to the matrix.

FIG. 6.

Majority of the HMWC of Hg18ΔN72 or SA11ΔN72 proceed through ordered multimerization of tetramers as demonstrated by glutaraldehyde cross-linking. ΔN85 (lane 1), Hgm1 (lane 2), Hgm15 (lane 3), Hg18ΔN72 (lane 4, 1 h; lane 5, 4 h; lane 6, 12 h) at 5 nmol (at an approximately 600-μg/ml concentration); the oligomeric form of SA11dirm2 (lane 7) at 2 nmol (3 μg/ml in 8 ml for 12 h); and the protein eluting at an apparent molecular weight of 36 to 39 of SA11dirm4 (lane 8) were cross-linked using an equimolar ratio (1:1) of cross-linker to protein for indicated time periods. Note tetramers of all the mutants and a range of multimers proceeding through tetramers of ΔN72 at 1 h of cross-linking (lane 4), HMWC of ΔN72 that barely migrated into the resolving gel (lane 5, 4 h), and HMWC that remained just below the well in the stacking gel (lane 6, 12 h). The start of resolving and stacking gels and the positions of monomeric, dimeric, and tetrameric forms are indicated by arrows. At a high ratio of cross-linker to protein (100:1 or 200:1), the majority of ΔN72 goes into HMWC within 5 min of cross-linking (data not shown). At a 3.0-μg/ml concentration, only tetramers of dirm2 and dirm4 are seen (lanes 7 and 8), but at 10 μg/ml, multimers are also observed (data not shown). M, protein molecular weight markers.

Thioflavin T binding to NSP4 deletion mutants.

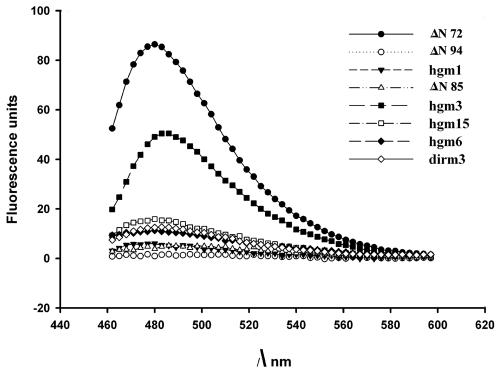

ThT is known to undergo a red shift of its fluorescence excitation and emission upon binding to amyloid or polymeric structures (16, 43). In the absence of binding to the protein, ThT has a low-fluorescence quantum yield with excitation and emission maxima at 350 and 438 nm, respectively. Upon binding of ThT to amyloid fibrils, the fluorescence quantum yield increases significantly and excitation and emission maxima are shifted to 450 and 482 nm, respectively (43). ThT was employed to investigate whether the HMWC formed by ΔN72 and other mutants were ordered polymeric structures, amorphous aggregates, or amyloid fibrils. As shown in Fig. 7, only ΔN72 exhibited a high increase (>60-fold) in ThT fluorescence. All other mutant proteins, including those that were able to form multimers to different extents, showed negligible or total loss of binding to ThT. Among the DIR mutants, dirm3 was better than others in ThT binding. Hgm3 and dirm3, though multimerized as effectively as ΔN72, showed <50% and 10% ThT binding, respectively, of that of ΔN72.

FIG. 7.

Fluorescence emission spectra of thioflavin T in the presence of NSP4 mutant proteins. Excitation wavelength was 450 nm. Total protein used for each of the mutants was 25 μmol. Only in the presence of ΔN72, ThT exhibited a large increase (>60-fold) in fluorescence compared to other mutants. Note that the single-amino acid mutant, Hgm3 (F76S), showed about 50% and the triple-amino acid mutant of DIR (dirm3) about 10% of fluorescence of that of ΔN72.

CD spectroscopic studies.

Far UV-CD spectroscopy was employed to probe the secondary structure and higher-order assembly products of the NSP4 mutant proteins. At 25°C and a total chain concentration of 10 μM, the CD spectra showed minima at 208 and 222 nm for the mutants. The relatively high negative (θ)MRE values are characteristic of α-helical coiled-coil structures (data not shown). Of note, ΔN85 showed a shift in the minimum of 208 nm to 205 nm. The (θ)MRE values for ΔN85 and all other mutants were significantly less than those for ΔN72 (data not shown). However, dirm1 showed a profile that was similar to that for ΔN72. At a total chain concentration of 10 μM, both ΔN85 and ΔN94 showed thermal unfolding profiles that were sigmoidal and reversible, which is characteristic of a cooperative helix coil transition. While the melting profile of ΔN94 was sharp, that exhibited by ΔN85 was gradual and less cooperative. In spite of the differences in melting profiles, both showed a melting temperature (Tm) of around 43 to 44°C (Table 2). In contrast, ΔN72 exhibited a profile that indicated an incomplete thermal unfolding transition between 10 and 100°C, possibly due to the association of tetrameric coiled coils into thermostable multimers. While the α-helical and β-sheet conformation contents of ΔN72 and dirm1 predicted by the k2d method (2) were 62 and 59% and 6 and 8%, respectively, the corresponding values for all other mutants ranged between 44 and 53% and 20 and 23% (Table 2). The proportion of random conformations among all the mutant proteins was very similar and ranged from 31 to 33% (Table 2). Each of the N- and C-terminal mutants and the DIR mutants exhibited incomplete thermal unfolding profiles that are distinct from that of ΔN72 as well as from each other, and hence, the Tm values reported in Table 2 represent only approximate values. Hgm3 and dirm3, which were similar to ΔN72 in multimerization ability, as observed by SEC, also exhibited distinct thermal melting profiles and Tm values, suggesting conformational differences among these mutants.

TABLE 2.

Percent α-helical, β-sheet, and random conformations of different mutants of NSP4 from Hg18 and SA11 strainsa

| Mutant | Content (%)

|

Tm (°C) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Helix | β-Sheet | Random coil | ||

| Hg18ΔN72 | 62 | 6 | 31 | >81 |

| Hg18ΔN85 | 47 | 22 | 31 | 43 |

| Hg18ΔN94 | 45 | 23 | 31 | 44 |

| Hgm1 | 45 | 23 | 31 | 55 |

| Hgm3 | 44 | 23 | 31 | ∼68 |

| Hgm6 | 45 | 23 | 31 | ∼66 |

| Hgm15 | 47 | 20 | 32 | ∼66 |

| SA11ΔN72 | 61 | 7 | 32 | >80 |

| SA11ΔN85 | 47 | 21 | 32 | 44 |

| SA11dirm1 | 59 | 8 | 33 | ∼70 |

| SA11dirm2 | 46 | 23 | 31 | ∼71 |

| SA11dirm3 | 45 | 23 | 32 | ∼72 |

| SA11dirm4 | 53 | 14 | 33 | ∼77 |

Note that both N- and C-terminal mutants of ΔN72 exhibit properties, except for Tm values, similar to those of ΔN85 which lacks AAH73-85. The G140A mutant dirm1 exhibits similar α-helical and β-sheet conformation contents but a different Tm value compared to ΔN72. Among all the mutants, ΔN72 from both strains exhibits the highest α-helical and least β-sheet contents. The Tm values of the ΔN72, Hgm3, Hgm6, Hgm15, and DIR mutants represent approximate values since the proteins exhibit incomplete thermal unfolding profiles that are distinct from each other.

Differential susceptibility of NSP4 mutant proteins to trypsin digestion.

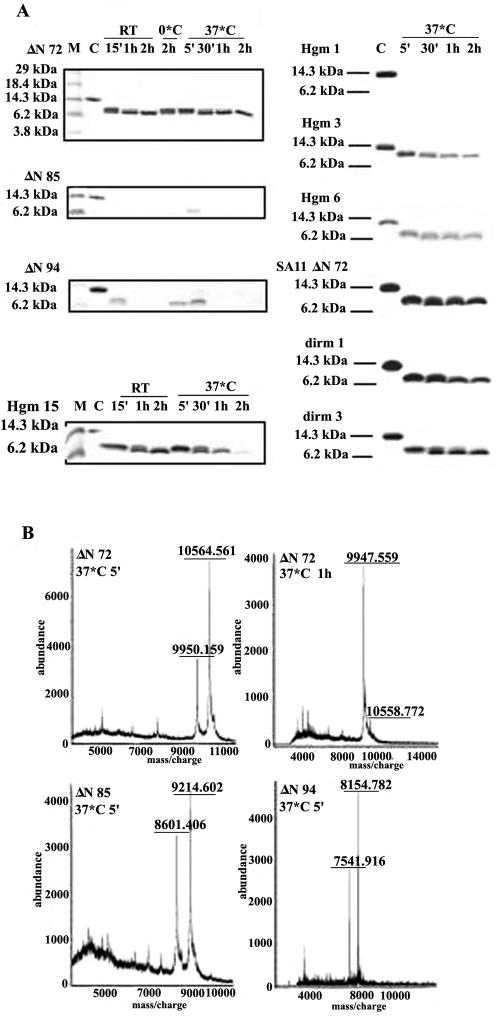

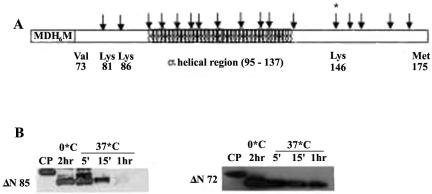

To determine if multimerization of oligomers into thermostable complexes also confers resistance against cleavage by proteases, the mutant NSP4 proteins from Hg18 and the DIR mutants from SA11 were subjected to trypsin digestion at different temperatures. As shown in Fig. 8A and 8B, 10.56- and 9.95-kDa fragments derived from Hg18ΔN72, 9.22- and 8.60-kDa fragments from Hg18ΔN85, and 8.16- and 7.54-kDa fragments from Hg18ΔN94 were protected when subjected to limited digestion by incubation on ice, at RT, or at 37°C. In the case of ΔN72, the larger, 10.56-kDa product underwent processing in a time-dependent manner into the smaller, 9.95-kDa fragment that remained stable even after 2 h of incubation at 37°C (Fig. 8A and 8B). However, by 30 min at RT or 37°C, both fragments of ΔN85 and ΔN94 were totally degraded even before the larger fragment got fully converted to the smaller one (Fig. 8A). While Hgm1 was highly susceptible to trypsin digestion, Hgm3, Hgm6, and Hgm15 showed trypsin susceptibility that was intermediate to that exhibited by ΔN85 and ΔN72 (Fig. 8A). After a 2-h incubation, very little of Hgm3, Hgm6, and Hgm15 remained resistant to trypsin. However, all the DIR mutants were relatively more resistant to trypsin cleavage than the N- and C-terminal mutants but were less stable than ΔN72 (Fig. 8A). Limited proteolysis of a deletion mutant equivalent to ΔN85 from the SA11 strain (45) identified lysine 146 as the C-terminal boundary of the 8.347-kDa protease-resistant fragment (Fig. 5 and 9A). Western blot analysis of the trypsin cleavage products of ΔN72 revealed the presence of an intact N terminus (Fig. 9B). From the observed sizes of the fragments derived from the N-terminal-tagged ΔN72, ΔN85, and ΔN94 and previously published results (45, 57), it can be concluded that the primary product of trypsin digestion is formed by cleavage at lysine 151 and that the final trypsin-resistant fragment is derived by further cleavage at lysine 146.

FIG. 8.

Differential susceptibility of Hg18 and SA11 NSP4 mutant proteins to trypsin cleavage. (A) Tricine-SDS-PAGE of the trypsin cleavage products. Note the 9.95-kDa trypsin-resistant fragment derived from ΔN72. Note the significant resistance of the DIR mutants to trypsin cleavage. The conditions and time period of incubation are indicate above the gels. Similar results were obtained using corresponding mutants of SA11 (data not shown). (B) Mass spectra of trypsin cleavage products of NSP4 mutants. Time-dependent conversion of the 10.56-kDa primary cleavage product to 9.95-kDa stable product between 5 min and 1 h is shown for ΔN72. The corresponding products of ΔN85 and ΔN94 are seen only at very early time points of trypsin treatment.

FIG. 9.

Protection from trypsin cleavage of the region N terminus to aa 146 in ΔN72. (A) Diagramatic representation of the predicted trypsin cleavage sites (arrows) on NSP4ΔN72 of SA11 (7, 12). His tag (H6) at the N terminus is indicated. Previously mapped C-terminal boundary of trypsin cleavage at aa 146 on SA11 NSP4 is indicated by *. For the amino acid sequence of this trypsin-resistant region, refer to Fig. 4A. (B) Western blotting and detection of the trypsin-resistant fragments of Hg18ΔN72 and Hg18ΔN85 using mouse anti-His horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (QIAGEN).

Diarrhea-inducing ability of NSP4 mutant proteins.

To evaluate the effect of differences in conformation and trypsin susceptibility among the mutants on biological activity, if any, the mutant proteins were tested for their ability to induce diarrhea in newborn mouse pups. As shown in Table 3, ΔN72 from the simian strain SA11 and bovine strain Hg18 exhibited comparable DD50 values in the range of 0.005 to 0.006 nmol. In contrast, while the DD50 value for ΔN85 from Hg18 was about 17-fold lower (0.60 nmol) than that for Hg18ΔN94, that for SA11ΔN85 was approximately 80-fold lower (0.05 nmol) than that for ΔN94 from the same strain. The diarrhea-inducing capacity of Hg18ΔN94 and SA11dirm1 was the lowest among all the mutants, with a DD50 of 10 nmol. The DD50 value for Hg18 ΔN57 was similar to that for ΔN72 (data not shown). Thus, SA11ΔN72 was about 10- and 800-fold more potent than ΔN85 and ΔN94, respectively, of the same strain but was about 100- and 2,000-fold more potent than the corresponding mutants of Hg18 (Table 3). Significantly, while mutants of the DIR of SA11ΔN72 exhibited DD50 and diarrheal scores that were approximately similar to those for the corresponding ΔN94, the N- and C-terminal mutants of Hg18ΔN72 exhibited DD50 and diarrheal scores similar to that for ΔN85 of the same strain (Table 3). Of great significance, the single conservative substitution at amino acid position 139 (T139S) in ΔN72 (dirm4) had a deleterious effect on the diarrhea-inducing ability, with a DD50 value similar to that for SA11ΔN94. While the G140A substitution (dirm1) in the background of dirm4 further decreased the diarrhea-inducing ability by five times, the double-amino acid mutant dirm2 and the triple-amino acid mutant dirm3 showed a twofold reduction in diarrhea induction compared to the single-amino acid mutant dirm4.

TABLE 3.

Summary of trypsin resistance and diarrhea-inducing ability in newborn mouse pups of N- and C-terminal and DIR mutants of NSP4 from SA11 and Hg18 strains

| Mutant proteins | DD50a

|

Fold efficiency of diarrhea inductionb | Trypsin resistancec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| μg | nmol | |||

| Hg18ΔN72 | 0.08 | 0.006 | 1,666 | ++++ |

| Hg18ΔN85 | 7.07 | 0.6 | 17 | − |

| Hg18ΔN94 | 100.0 | 10.0 | 1 | − |

| Hgm1 | 7.0 | 0.53 | 19 | − |

| Hgm3 | 4.4 | 0.33 | 30 | ++ |

| Hgm6 | 4.8 | 0.36 | 28 | ++ |

| Hgm15 | 12.5 | 0.9 | 11 | + |

| SA11ΔN72 | 0.075 | 0.005 | 800 | ++++ |

| SA11ΔN85 | 0.589 | 0.05 | 80 | − |

| SA11ΔN94 | 40.0 | 4.0 | 1.0 | − |

| SA11dirm1 | 133.0 | 10 | 0.4 | +++ |

| SA11dirm2 | 52.2 | 4.0 | 1.0 | +++ |

| SA11dirm3 | 67.0 | 5.0 | 0.8 | +++ |

| SA11dirm4 | 26.8 | 2.0 | 2.0 | +++ |

To arrive at DD50 values, each mutant protein was tested at concentrations ranging from 1 pmol to 20 nmol. At each dose, eight mouse pups were used and the experiment was repeated two to four times. A total of 2,400 mouse pups were used for the enterotoxigenic assay. Relevant mean diarrheal scores are discussed in the text. The mean diarrheal scores of the N- and C-terminal mutants of ΔN72 were very similar to that exhibited by ΔN85, and those of the DIR mutants were similar to that of ΔN94.

Fold efficiency of diarrhea induction for different mutants of a strain was calculated with reference to the DD50 of ΔN94 of the corresponding strain.

−, degraded by trypsin in 5 to 15 min at 37°C; ++++, resistant to trypsin even after 2 h; +, resistant up to 1 h; ++ and +++ correspond to about 50% and 75% of the peptide being resistant, respectively, compared to that of ΔN72 at 2 h.

Furthermore, the time of onset of diarrhea as well as the mean diarrheal score varied with the dose of each mutant. ΔN72 induced diarrhea at about 30 min after administration of the protein, and the pups excreted diarrheic stools rapidly up to a dose of 0.1 nmol. The mean diarrheal scores at 5 nmol and 0.005 nmol were 3.2 and 2.0, respectively. At doses of 5.0 nmol and above, ΔN85-administered mice behaved similar to those given 1.0 and 0.1 nmol ΔN72. At a dose lower than 0.1 nmol of ΔN72 and 5 nmol of ΔN85 and above 1 nmol of ΔN94, diarrhea was observed between 45 min and 1 h only after gentle pressing of the abdomen, with a mean diarrheal score of 2.0. The diarrheal score did not significantly change with the dose of ΔN94. Mouse pups administered PBS, NSP5, or the C-terminal 164-amino acid fragment of rotavirus NSP3 never excreted diarrheic stools.

Thus, evaluation of the diarrhea-inducing ability of different mutants of Hg18ΔN72 and SA11ΔN72 revealed that, while deletions or amino acid substitutions in AAH73-85 or the C terminus resulted in a 50- to 150-fold increase in DD50 values, mutations in DIR had a more drastic effect, resulting in a 400- to 2,000-fold reduction. Surprisingly, Hgm3 and dirm3, which were as effective as ΔN72 in multimerization and were significantly resistant to trypsin digestion, exhibited DD50 values that were about 66- and 1,000-fold higher, respectively, than those for the corresponding ΔN72.

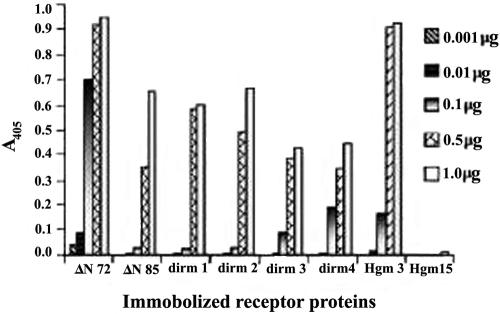

DLP-binding activity of ΔN72 mutants.

Using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay method, the effect of mutations in the DIR and N- and C-terminal regions on the DLP-binding ability of the mutants was assessed. As shown in Fig. 10, while ΔN72 was able to capture DLPs at a very low concentration (0.001 μg), ΔN85 and all other mutants of ΔN72 required 100-fold more receptor to bind DLPs equivalent to that bound by 0.001 μg ΔN72. However, at a high concentration, except Hgm15, all the mutants showed a significant level of DLP binding but less than that for ΔN72. Of note, at a high concentration, the DLP-binding activity of Hgm3 was comparable to that of ΔN72. In contrast, Hgm15 failed to bind a significant amount of DLPs, even at a high receptor concentration. It may be noted that Hgm3 and dirm3, which were as effective in multimerization as ΔN72, as observed by SEC, were similar to other mutants that did not multimerize or inefficiently multimerized in DLP binding at low concentration (Fig. 10).

FIG. 10.

DLP-binding activity of different SA11 NSP4 mutants. Note that all the mutants failed to bind DLPs at low concentration and required 100-fold more protein to bind DLPs equivalent to that bound by 0.001 μg of ΔN72. The C-terminal methionine mutant Hgm15 did not bind DLPs even at high concentration. At high concentration, the DLP-binding activity of Hgm3 is similar to that of ΔN72.

DISCUSSION

Since the primary objective of this study was to investigate the influence of N-and C-terminal regions and the DIR, including the interspecies variable region of the CT, on its structural and biological properties, initially, the properties of three deletion mutants having truncations at the N terminus were examined by a variety of methods, which suggested that a stretch of 13 aa at the N terminus of ΔN72, predicted to fold as an amphipathic α-helix, promoted multimerization of the CT. Cross-linking data also suggested that the majority of the multimers of ΔN72 proceeded through the ordered aggregation of tetramers. Earlier studies on the expression of truncated mutants of NSP4 in E. coli suggested a minimal membrane permeabilization region to be located within residues 48 to 91 (11) and that a predicted amphipathic helix located between aa 55 to 72 possessed membrane-destabilizing activity in mammalian cells (44). The present study also reveals that the region from aa 48 to 72 is toxic to E. coli and that the membrane destabilization activity is not associated with AAH73-85 since ΔN72 was expressed at high levels in soluble form. The observation that diverse cellular proteins contain motifs highly related to the predicted AAH73-85 of NSP4 further suggests that this motif by itself does not contribute to the membrane destabilization. It is of significance that the hydrophilic side of AAH55-72 consists totally of basic amino acids in contrast to the uncharged polar amino acids, except for a single lysine that constitutes the hydrophilic side of AAH73-85 (Fig. 4A and 4B).

Both the predicted AAH73-85 at the N terminus and an intact C terminus in ΔN72 appear to be necessary for efficient multimerization of the 12.16-kDa region of the CT into soluble high-molecular-mass complexes. Mutants that either lacked the N-terminal motif (ΔN85, ΔN94) or contained the motif having several amino acid substitutions (Hgm1) failed to multimerize and existed only as tetramers of an apparent molecular weight ranging from 54,000 to 58,000, which is greater than that expected for a tetramer, suggesting the flexible nature of the C-terminal region downstream of the coiled-coil region, as suggested previously (57). However, the C-terminal mutants and the DIR mutants dirm1 and dirm2 exhibited an oligomer of apparent molecular mass ranging from 46 to 53 kDa that suggested conformational differences among the tetramers of different mutants. The observation that multimerization of the C-terminal mutants was dependent on concentration suggests that an intact C terminus is required for stability of the multimers. These results strongly suggest head-to-tail cooperation/interaction in ΔN72. The finding that mutations in either the N-terminal AAH73-85 or the extreme C terminus or the DIR profoundly affected multimerization strongly suggests that multimerization is dependent on a specific conformation conferred by the cooperation between the two termini and that only those oligomeric forms having a specific conformational state/site, which appears to encompass the entire CT, undergo rapid multimerization even at a very low concentration. The hypothesis that each of the mutants differed in conformation of the oligomeric and multimeric forms and their stabilities is strongly supported by their distinct CD and melting profiles as well as melting temperatures (Table 2). Interaction between the N and C termini or anchoring of the loose ends has been reported to be a mechanism of stabilization of the protein structure (40, 61). Multimerization of ΔN72 may be of biological relevance since high-molecular-weight forms of full-length NSP4, C-terminal methionine mutant, or NSP4Δ1-53 were reported in virus-infected cells or in cells transfected with vectors expressing the proteins (34, 58).

The selective and efficient binding of ThT to ΔN72 but not to any of the mutants is intriguing since ΔN72 is predicted to have more α-helical and less β-sheet content than the other mutants (Table 2). Though this fluorophore has been extensively used for the detection of amyloid and ordered polymeric structures in proteins (16, 31, 43), its binding mode to amyloid or the physical basis for ThT fluorescence is poorly understood (31, 43). Examination of ΔN72 under a transmission electron microscope did not reveal the presence of characteristic amyloid fibrils, but only reticulate structures (data not shown), a detailed analysis of which is in progress. It is possible that ThT specifically recognizes a unique conformational state in ΔN72. Support for this hypothesis comes from a recent study in which ThT was observed to exhibit more than 1,000-fold enhancement in fluorescence upon binding to the peripheral ligand-binding site in acetylcholinesterase that was suggested to be dependent on specific conformation rather than the β-sheet structure of the peripheral ligand-binding site (19). In spite of a lack of understanding of the physical basis of ThT interaction with proteins, the fact that mutations in different regions abrogated or severely reduced ThT fluorescence suggests conformation-dependent binding of ThT to ΔN72 and this selective binding may be used to distinguish between highly enterotxigenic and attenuated forms of NSP4.

Previous studies showed that the conserved C-terminal methionine is important for DLP-binding activity and that amino acid substitution or deletion at this position abolished DLP binding in the context of C90 of the CT. It was suggested that the conformational integrity of the C terminus might be important for the receptor property of the protein (5, 45, 58). Our results reveal that all the mutants, unlike ΔN72, irrespective of the site and type of mutation, failed to bind DLPs at low receptor concentration. As shown in Fig. 10, all the mutants, with the exception of the C-terminal methionine mutant Hgm15, required 100-fold more protein to bind DLPs equivalent to that bound by 0.001 μg of ΔN72. However, the DLP-binding capacity of all the mutants, irrespective of their multimerization ability, is significantly restored at high concentration of the receptor. In contrast, Hgm15 showed negligible binding of DLPs even at high protein concentration. In an earlier study, a C-terminal methionine mutant equivalent to ΔN85 was also shown to lack DLP binding and it was suggested that the C-terminal methionine forms part of the receptor-binding domain in the tetramer (56, 58). NSP4-DLP interaction appears to involve positive cooperativity of binding driven by multiple interactions between the receptor and multiple binding sites on the surface of DLP (56, 58). Our results indicate that the cooperativity of binding at low concentration of the receptor having a high-affinity binding domain is potentiated by multimerization and mutants having a suboptimal ligand-binding domain that either multimerize or do not multimerize requires high concentration for cooperativity of binding. This is exemplified by the observation that Hgm3 that multimerizes similar to ΔN72 fails to bind DLPs at low concentration but binds as efficiently as ΔN72 at high concentration. All of these results strongly suggest that the CT forms a large conformation-dependent DLP-binding domain with the C-terminal methionine occupying a crucial position. Multimerization alone is not sufficient for efficient binding of DLPs, but a specific conformation in the oligomer is necessary for high-affinity DLP binding of the CT that could be partially overcome at high concentration of the receptor.

Among the mutants tested, ΔN72 from both SA11 and Hg18 was the most potent in diarrhea induction, exhibiting DD50 values and diarrheal scores in the range of 0.005 nmol and 3.2, respectively. It is of interest to note that NSP4 from Hg18 differed from that of SA11 in the diarrhea-inducing region at positions 131, 135, and 138 (Fig. 5A). While the substitution of Tyr131 in a synthetic peptide from aa 114 to 135 corresponding to SA11 NSP4 reduced its diarrhea-inducing ability (6), mutations at either 135 or 138 have been implicated in the attenuation of virus virulence of two porcine strains and loss of diarrhea-inducing ability of the protein (65). In spite of these differences, the DD50 for ΔN72 from both the strains was very similar, suggesting that the effect of a mutation at a particular position could be compensated for by mutations at specific positions in other regions of the protein. Evaluation of single-, double-, and triple-amino acid substitution mutants involving positions 131, 139, and 140 in the DIR in the context of SA11ΔN72 revealed severe loss in the diarrhea-inducing ability of all the DIR mutants, which is in accordance with the previously published results (65). It is of interest to note that the triple-amino acid mutant of DIR (dirm3), though able to multimerize similar to ΔN72 and Hgm3, exhibited about 1,000- and 15-fold higher DD50 values than the two mutants, respectively. Even the conservative amino acid substitution T139S resulted in the severe loss of diarrhea-inducing activity. It may be noted that Zhang et al. (65) previously reported that the conservative V135A mutation resulted in the loss of virulence of two porcine strains. Several strains possess either a proline at amino acid position 138 or a glycine at amino acid position 140. Among the DIR mutants, dirm1 (G140A) showed the highest DD50, suggesting that the presence of a helix-breaking amino acid at either of the positions is important for efficient cooperation between the two terminal regions, which in turn facilitates formation of the specific conformational domain in the CT and its multimerization. Multimerization of the tetramer having proper conformation might potentiate the diarrhea-inducing ability of ΔN72 by conferring prolonged resistance to the DIR against protease digestion. It is noteworthy that in spite of the multimerization into HMWC, the extreme C terminus from aa 147 to 175 is still susceptible to trypsin cleavage.

The observation that dirm1 and dirm2, though inefficient in multimerization, were significantly resistant to trypsin digestion but were severely compromised in diarrhea induction suggests that multimerization is not a prerequisite for resistance to trypsin cleavage. Interestingly, while all the N- and C-terminal mutants of Hg18ΔN72 showed DD50 values that are about 50- to 150-fold higher than that of ΔN72 but similar to that of ΔN85, the amino acid substitution mutants of the DIR of SA11 were 500- to 1,500-fold less potent than SA11ΔN72 and were approximately similar to SA11ΔN94 in diarrhea induction (Table 3). The observation that the 9.95-kDa trypsin cleavage product from ΔN72 and the DIR mutants is highly resistant to trypsin indicates that both AAH73-85 and an intact C terminus are necessary for protection against trypsin digestion of the region from aa 73 to 146. The fact that the diarrhea-inducing ability is severely affected by mutations in either of the termini or the DIR, including the ISVD, further suggests that the diarrhea-inducing potential of the protein is highly dependent on a specific conformational state/site in ΔN72 conferred by the cooperation between the two termini in the oligomer from Hg18 and SA11. It is important to note that while the conformational changes effected by mutations in the N- and C-terminal regions rendered the DIR highly susceptible to proteolytic cleavage, those induced by mutations within the DIR did not significantly affect resistance to trypsin in spite of the fact that this region contains several potential cleavage sites for the protease (Fig. 8A). These observations indicate that subtle differences in conformation due to mutations in the DIR, including the ISVD, may or may not result in trypsin susceptibility but could have a severe effect on enterotoxigenic activity.

Rotavirus infection can be either symptomatic or asymptomatic. Although earlier studies predicted the asymptomatic phenotype to be associated with a unique VP4 type (21), subsequent studies revealed no such correlation (51). The discovery of NSP4 as the viral enterotoxin (6) provided a new direction toward understanding the molecular basis for the virulence/avirulence character of rotavirus. Although the NSP4 gene from more than 175 symptomatic, asymptomatic, human, animal, and avian strains has been sequenced to date, no correlation between sequence variation in NSP4 and the virulence/avirulence phenotype of the virus could be inferred by comparative sequence analysis (32). It is noteworthy that the sequence in AAH73-85 is highly conserved among different group A rotaviruses. A frequently observed conservative substitution in different strains was at position 76, where a Phe, Leu, or Ile that neither affected the predicted amphipathic α-helical conformation nor correlated with the virulence/avirulence character of the virus was seen. However, the nonconservative F76S substitution, though it did not affect multimerization ability, severely affected both diarrhea-inducing and DLP-binding properties. Furthermore, the C-terminal methionine is highly conserved among different symptomatic and asymptomatic strains with the exception of rhesus rotavirus, murine, feline, or feline-derived reassortant strains (26, 32). Significantly, NSP4 proteins from different strains exhibit the greatest sequence variation in the relatively unstructured region about 40 aa from the C terminus (26, 32). In this context, it is possible that different NSP4s would widely differ not only in their diarrhea-inducing abilities in the newborn mouse model system, as reported for NSP4s from a few strains (6, 24, 41), but other properties as well. The 50- to 2,000-fold reduction in diarrhea induction observed for the mutants of the N- and C-terminal regions and the DIR strongly supports this hypothesis. It would be of interest to examine the influence of amino acid substitutions observed in the NSP4 from asymptomatic strains on multimerization, susceptibility to trypsin cleavage, diarrhea induction in newborn mouse pups, and DLP binding in comparison to NSP4 from symptomatic strains. Experiments to evaluate this hypothesis are currently in progress.

Increased protease resistance and enhanced thermal stability of the mutants containing AAH73-85 strongly suggests that this region contributes to the overall folding of the protein. The relative protease sensitivity of similar mutants that also contain mutations at the C terminus, DIR, or ISVD suggests that these regions are also important to the overall fold. The finding of the protease-resistant core could lead to structural analysis of the region, provided the tendency to form multimeric structures can be overcome.

In conclusion, our results obtained employing a variety of methods and a large number of mutants of NSP4 from two strains provide strong evidence, for the first time, for cooperation between the N- and C-terminal regions that appears to result in the formation of a complex and unique conformational domain in the oligomer that facilitates the efficient multimerization of the CT. The fact that both diarrhea-inducing ability and DLP-binding activity are severely affected by the same mutations in either of the termini or the DIR, including the predicted relatively unstructured ISVD, strongly indicates that a single and/or overlapping conformation-sensitive domain mediates both the functions. Significantly, the apparent specific recognition of a conformation-sensitive site in ΔN72 by ThT, resulting in high fluorescence emission, correlated with the diarrhea-inducing ability of the protein, which could be used as a simple means of identification of NSP4s that are highly enterotoxigenic in newborn mice and could lead to significant reduction in the number of mice used in determining DD50 values. Since the diarrhea-inducing ability of ΔN72 is comparable to that reported for full-length protein, considering the difficulties encountered in the expression and purification of full-length NSP4, comparative analysis of the biophysical, biochemical, and biological properties of ΔN72 from different symptomatic and asymptomatic strains should facilitate understanding the basis of the NSP4-mediated virulence and reveal if a correlation exists between the virulence phenotype of the virus in the homologous host and the diarrhea-inducing property of the cognate NSP4 in the mouse model. In the absence of a three-dimensional structure due to difficulties encountered in crystallization of the protein, the present study provides valuable insights for a novel conformation-based rationale for understanding the pleiotropic properties of the rotavirus enterotoxin, including the mechanism of viral morphogenesis and pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Vinod Bhakuni, CDRI, Lucknow, and C. Mohan Rao, Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology, Hyderabad, India, for their valuable suggestions on CD experiments. We gratefully acknowledge the use of the CD and mass spectrometry facilities in the Molecular Biophysics Unit and the CD facility in the Department of Biochemistry at the Indian Institute of Science. We thank M. Govindaraja for the help with CD measurements.

This work was supported by grants from the Indian Council of Medical Research and the Structural Genomics program under the Genomics Initiative at the Indian Institute of Science, funded by the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., J. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programmes. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrade, M. A., P. Chacon, J. J. Merelo, and F. Moran. 1993. Evaluation of secondary structure of proteins from UV circular dichroism using an unsupervised learning neural network. Protein Eng. 6:383-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angel, J., B. Tang, N. Feng, H. B. Greenberg, and D. Bass. 1998. Studies of the role for NSP4 in the pathogenesis of homologous murine rotavirus diarrhea. J. Infect. Dis. 177:455-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Au, K.-S., W. K. Chan, J. W. Burns, and M. K. Estes. 1989. Receptor activity of rotavirus nonstructural glycoprotein NS28. J. Virol. 63:4553-4562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Au, K.-S, N. M. Mattion, and M. K. Estes. 1993. A subviral particle binding domain on the rotavirus nonstructural glycoprotein NS28. Virology 194:665-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ball, J. M., P. Tian, C. Q.-Y. Zeng, A. P. Morris, and M. K. Estes. 1996. Age-dependent diarrhea induced by a rotaviral nonstructural glycoprotein. Science 272:101-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergmann, C. C., D. Mass, M. Poruchynsky, P. H. Atkinson, and A. R. Ballamy. 1989. Topology of the nonstructural rotavirus receptor glycoprotein NS28 in the rough endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J. 8:1695-1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borgan, M. A., Y. Mori, N. Ito, M. Sugiyama, and N. Minamoto. 2003. Antigenic analysis of nonstructural protein (NSP) 4 of group A avian rotavirus strain PO-13. Microbiol. Immunol. 47:661-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boshuizen, J. A., J. W. A. Rossen, C. K. Sitaram, F. F. P. Kimenai, Y. Simons-Oosterhuis, C. Laffeber, H. A. Büller, and A. W. C. Einerhand. 2004. Rotavirus enterotoxin NSP4 binds to the extracellular matrix proteins laminin-β3 and fibronectin. J. Virol. 78:10045-10053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowman, G. D., I. M. Nodelman, O. Levy, S. L. Lin, P. Tian, T. J. Zamb, S. A. Udem, B. Venkataraghavan, and C. E. Schutt. 2000. Crystal structure of the oligomerization domain of NSP4 from rotavirus reveals a core metal-binding site. J. Mol. Biol. 304:861-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Browne, E. P., A. R. Bellamy, and J. A. Taylor. 2000. Membrane-destabilizing activity of rotavirus NSP4 is mediated by a membrane-proximal amphipathic domain. J. Gen. Virol. 81:1955-1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan, W.-K., K. S. Au, and M. K. Estes. 1988. Topography of the simian rotavirus nonstructural glycoprotein (NS28) in the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Virology 164:435-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang, K. O., Y. J. Kim, and L. J. Saif. 1999. Comparisons of nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of NSP4 genes of virulent and attenuated pairs of group A and C rotaviruses. Virus Genes 18:229-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deepa, R., M. R. Jagannath, M. M. Kesavulu, C. Durga Rao, and K. Suguna. 2004. Expression, purification, crystallization and preliminary crystallographic analysis of the diarrhoea-causing and virulence-determining region of rotaviral nonstructural protein NSP4. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D 60:135-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delmas, O., A.-M. Durand-Schneider, J. Cohen, O. Colard, and G. Trugnan. 2004. Spike protein VP4 assembly with maturing rotavirus requires a postendoplasmic reticulum event in polarized Caco-2 cells. J. Virol. 78:10987-10994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devlin, G. L., M. K. M. Chow, G. J. Howlett, and S. P. Bottomley. 2002. Acid denaturation of α1-antitrypsin: characterization of a novel mechanism of serpin polymerization. J. Mol. Biol. 324:859-870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong, Y., C. Q.-Y. Zeng, J. M. Ball, M. K. Estes, and A. P. Morris. 1997. The rotavirus enterotoxin mobilizes intracellular calcium in human intestinal cells by stimulating phospholipase C mediated inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:3960-3965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Estes, M. K. 2001. Rotaviruses and their replication, p. 1747-1785. In D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, D. E. Griffin, R. A. Lamb, M. A. Martin, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Fields virology, vol. 2. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrari, G. V., W. D. Mallender, N. C. Inestrosa, and T. L. Rosenberry. 2001. Thioflavin T is a fluorescent probe of the acetylcholinesterase peripheral site that reveals conformational interactions between the peripheral and acylation sites. J. Biol. Chem. 276:23282-23287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldgur, Y., F. Dyda, A. B. Hickman, T. M. Jenkins, R. Craigie, and D. R. Davies. 1998. Three new structures of the core domain of HIV-1 integrase: an active site that binds magnesium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:9150-9154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gorziglia, M., K. Green, K. Nishikawa, K. Taniguchi, R. Jones, A. Z. Kapikian, and R. M. Chanock. 1988. Sequence of the fourth gene of human rotaviruses recovered from asymptomatic or symptomatic infections. J. Virol. 62:2978-2984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenfield, N., and G. D. Fasman. 1969. Computed circular dichroism spectra for the evaluation of protein conformation. Biochemistry 8:4108-4116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henning, L. 1999. WinGene/WinPep: user-friendly software for the analysis on amino acid sequences. BioTechniques 26:1170-1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horie, Y., O. Nakagomi, Y. Koshimura, T. Nakagomi, Y. Suzuki, T. Oka, S. Susaki, Y. Matsuda, and S. Watanabe. 1999. Diarrhea induction by rotavirus NSP4 in the homologous mouse model system. Virology 262:398-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoshino, Y., L. J. Saif, S.-Y. Kang, M. M. Sereno, W.-K. Chen, and A. Z. Kapikian. 1995. Identification of group A rotavirus genes associated with virulence of a porcine rotavirus and host range restriction of a human rotavirus in the gnotobiotic pig model. Virology 209:274-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jagannath, M. R., R. R. Vethanayagam, B. S. Y. Reddy, S. Raman, and C. D. Rao. 2000. Characterization of human symptomatic rotavirus isolates MP409 and MP480 having “long” RNA electropherotype and subgroup I specificity, highly related to the P6[1],G8 type bovine rotavirus A5, from Mysore, India. Arch. Virol. 145:1339-1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones, T. A. 1978. A graphics model building and refinement system for macromolecules. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 11:268-272. [Google Scholar]