Abstract

Human T-cell leukemia virus (HTLV) infection is a chronic, lifelong infection that is associated with the development of leukemia and neurological disease after a long latency period, and the mechanism by which the virus is able to evade host immune surveillance is elusive. Besides the structural and enzymatic proteins, HTLV encodes regulatory (Tax and Rex) and accessory (open reading frame I [ORF I] and ORF II) proteins. Tax activates viral and cellular transcription and promotes T-cell growth and malignant transformation. Rex acts posttranscriptionally to facilitate cytoplasmic expression of incompletely spliced viral mRNAs. Recently, we reported that the accessory gene products of HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 ORF II (p30II and p28II, respectively) are able to restrict viral replication. These proteins act as negative regulators of both Tax and Rex by binding to and retaining their mRNA in the nucleus, leading to reduced protein expression and virion production. Here, we show that p28II is recruited to the viral promoter in a Tax-dependent manner. After recruitment to the promoter, p28II or p30II then travels with the transcription elongation machinery until its target mRNA is synthesized. Experiments artificially directing these proteins to the promoter indicate that p28II, unlike HTLV-1 p30II, displays no transcriptional activity. Furthermore, the tethering of p28II directly to tax/rex mRNA resulted in repression of Tax function, which could be attributed to the ability of p28II to block TAP/p15-mediated enhancement of Tax expression. p28II-mediated reduction of viral replication in infected cells may permit survival of the cells by allowing escape from immune recognition, which is consistent with the critical role of HTLV accessory proteins in viral persistence in vivo.

Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) and HTLV-2 are distinct complex oncogenic retroviruses that persist in the infected individual despite a robust virus-specific host immune response (20). HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 share 65% homology at the nucleotide sequence level but remain distinct in their pathology. HTLV-1 is the causative agent of adult T-cell leukemia, a fatal malignancy of CD4+ T lymphocytes, and a chronic neurological disorder termed HTLV-1-associated myelopathy or tropical spastic paraparesis (18, 24, 45, 47). HTLV-2 has a less clear disease association in that only a few cases of variant hairy cell leukemia and neurological disease have been reported (26, 54, 55). HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 have the capacity to promote T-lymphocyte growth both in vitro and in vivo (22, 43, 52, 56). The ultimate fate of infected T cells in vivo depends on their ability to balance proliferative, cell cycle, and antiapoptotic signals mediated by viral and cellular proteins versus the ability to evade the host immune response. Therefore, how the virus responds to environmental signals and regulates viral and cellular gene expression is critical to its long-term survival and persistence in the infected individual.

Upon viral infection, reverse transcription and random integration of the proviral DNA into the host genome (57), the viral transactivator Tax directs HTLV gene expression from a promoter that is located in the 5′ long terminal repeat (5′LTR) (15). Three highly conserved 21-bp enhancer elements that are critical for Tax-mediated transcription are contained in the U3 region of the LTR and are referred to as Tax-response elements (TREs) or viral CREB response elements (4, 28). The cellular transcription factor CREB and/or other activating transcription factor (ATF)/CREB family members bind to the TREs, whereas Tax interacts with both CREB and the GC-rich DNA sequences that immediately flank the CREB binding site (30, 33, 34, 36). Tax-mediated protein-protein and protein-DNA interactions on the HTLV promoter lead to the assembly of very stable ternary complexes that are critical for the recruitment of the cellular coactivator CBP/p300 (19, 32), which subsequently results in strong transcriptional activation of the virus (17, 35). This transcriptional activation results in the expression of all viral mRNAs encoding structural and enzymatic proteins (Gag, Pol, and Env), trans-regulatory proteins (Tax and Rex), and accessory proteins (p12, p13, and p30 for HTLV-1 and p10, p11, p22, and p28 for HTLV-2) (20).

The HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 accessory proteins, encoded by open reading frames (ORFs) near the 3′ end of the viral genome (9, 31), are the least conserved between the two related viruses and have been shown to be dispensable for in vitro replication and immortalization of activated primary T lymphocytes (14, 21, 53). However, the accessory proteins have been shown to be essential for viral infectivity and persistence in vivo when a rabbit model of infection is used (2, 10, 11, 58; unpublished data). HTLV-1 p30II and HTLV-2 p28II are nuclear proteins encoded by ORF II that share minimal homology at the amino acid level. Recently, p30II and p28II have been shown to down-regulate tax/rex mRNA expression posttranscriptionally by binding to and retaining this mRNA in the nucleus (44, 61). Interestingly, both p28II and p30II are able to inhibit tax/rex mRNA only when the latter is expressed from a full-length proviral clone and not from a cDNA.

There is a growing body of evidence that the different stages of gene expression, from transcription to pre-mRNA processing to export to the cytoplasm and translation, are functionally and physically coupled (37, 38). For example, the mRNA export factors Yra1p and Sub2p are cotranscriptionally recruited to the mRNA via their interaction with Hpr1p, a component of the transcription elongation machinery (62). Similarly, factors involved in splicing and polyadenylation associate with the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II, positioning them close to their mRNA substrate and enabling efficient processing (3, 16, 25, 40). Collectively, these observations raise the question of whether the discrimination between a tax/rex mRNA expressed from a proviral clone or a cDNA by p28II or p30II is dependent on pre-mRNA processing and/or another cotranscriptional process. A link between HTLV-1 p30II and the transcriptional machinery is suggested by its ability to differentially modulate viral gene expression via its interaction with CBP/p300 and destabilization of the Tax-CREB interaction (64, 65).

To further characterize the role of p28II or p30II in posttranscriptional suppression of tax/rex mRNA and define how and when it is recruited to the mRNA, we reconstructed several cDNA plasmids to mimic the mRNA that is expressed from a full-length proviral clone. Our results show that the 5′ untranslated region (5′UTR) of the target RNA, as well as the intron sequences, plays a minimal role in mediating the inhibition. Conversely, we identified the component of the HTLV promoter, specifically Tax, as the factor required for efficient recruitment of p28II or p30II to the newly transcribed mRNA. Consistently, our chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments showed that these proteins are recruited cotranscriptionally and associate with the elongation machinery. Furthermore, we provide evidence that p28II itself does not exhibit transcriptional activity but inhibits tax/rex mRNA transport by overriding the TAP/p15 export pathway. These data reveal a complex interplay between the transcriptional machinery and the posttranscriptional regulation of tax/rex mRNA, thereby providing the first example of a retroviral protein that couples transcription with posttranscriptional inhibition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium. The medium was supplemented to contain 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine, penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml).

Plasmids.

The HTLV-2 proviral clone, pH6neo (8), was used in this study. pME-p30II-HA (42), cytomegalovirus (CMV)-p28II-AU1 (61), and the LTR-2-Luc Tax reporter plasmid (61) were described previously. 2x21-Luc, which contains a minimal promoter and two copies of the distal HTLV 21-bp repeat linked to luciferase, was a kind gift from S. Marriott. CMV-β-galactosidase (CMV-βgal) was used to control for transfection efficiency in each experiment.

The following are the sequences of the different cDNAs used to express HTLV-2 Tax, with numbers in parentheses based on proviral genome location: BC20.2 (Tax-2), partial exon 2 (bp 5091 to 5183), fused to exon 3 (bp 7214 to 8552); IY531, exon 1 (bp 316 to 447), fused to full-length exon 2 (bp 4044 to 5183) and fused to exon 3 (bp 7214 to 8552); IY587, equivalent to pH6neo proviral clone, but intron 1 is severely truncated (a fragment encompassing bp 1034 to 3634 is deleted, which eliminates gag and pol gene expression); IY588, equivalent to IY531, but the truncated intron 1 from IY587 is reinserted between exon 1 and exon 2; IY594, equivalent to BC20.2, but the full-length intron 2 is reinserted between exon 2 and exon 3; IY595, equivalent to IY531, but the full-length intron 2 is reinserted between exon 2 and exon 3; BCHTLV-2, equivalent to pH6neo, but the U3 region of the 5′LTR is replaced by a CMV immediate early promoter; IY619, equivalent to Tax-2, but the CMV promoter is replaced by the U3 region of the HTLV-2 LTR; IY620, equivalent to IY531, but the CMV promoter is replaced by the U3 region of the HTLV-2 LTR. TAP and p15 were transcribed from vectors under the control of a CMV promoter. For the Gal4 chimeras, the coding sequences of p28II or p30II were amplified by PCR to generate a BamHI-SacI fragment. The PCR product was ligated in frame downstream of the first 147 codons of the Gal4 DNA binding domain contained within the pSG424 plasmid (a kind gift from H. Bogerd, Duke University). For the MS2 fusion proteins, the coding sequences of p28II or green fluorescent protein (GFP) were amplified by PCR to generate a PacI-NotI fragment. The PCR product was ligated in frame downstream of the bacteriophage MS2 protein. The Tax2-MS2(RE) plasmid is equivalent to Tax-2 with six MS2 RNA response elements inserted between the Tax stop codon and the poly(A) signal.

Transfection, Tax functional assay, and Western blotting.

To measure Tax ATF/CREB-activating function (viral LTR), 2 × 105 293T cells were transfected using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The total amount of DNA was kept constant and was composed of 0.1 μg LTR-2-Luc, 50 ng CMV-βgal, and 0.2 to 0.4 μg of Tax expression plasmid, HTLV proviral clone, or empty control plasmid. To test the effect of p28II on Tax activity, increasing amounts of p28II expression plasmid (two and four times the amount of Tax expression plasmid) was cotransfected. After 48 h of growth, cells were pelleted and lysed in passive lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI), and Tax activity was measured as luciferase light units. All experiments were performed independently three times in triplicate, and results were normalized for transfection efficiency using β-galactosidase.

To measure Tax protein levels in the presence or absence of p28II, equivalent amounts of cell lysates from the functional assay were separated on 4 to 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against Tax-2, Rex-2, and p28II were used to detect the viral proteins. Rabbit polyclonal antibody to β-actin (Novus Biological, Littleton, CO) was used as a loading control (LC). Proteins were visualized using the ECL Western blotting analysis system (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

ChIP assay.

293T cells (2 × 105) were transfected using Lipofectamine with 0.5 μg of pH6neo or 0.1 μg LTR-2-Luc with or without 0.5 μg p28II or p30II expression plasmid. After 48 h of growth, cells were cross-linked with formaldehyde for 10 min at 37°C, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline, lysed in SDS lysis buffer, and sonicated on ice to generate DNA fragments between 100 to 1,000 bp. The ChIP assay was performed as recommended by Upstate Biotechnologies (Charlottesville, VA). Briefly, cell lysates were precleared with protein A-Sepharose beads and then incubated with anti-AU1 monoclonal antibody (p28II-AU1) or anti-HA monoclonal antibody (p30II-HA) overnight at 4°C. The immune complexes were captured on beads and washed extensively. The DNA-protein complexes were eluted, followed by treatment at 65°C for 4 h to reverse cross-linkages. DNA was then extracted using phenol-chloroform and ethanol precipitated.

PCR and primers.

PCR on extracted DNA from the ChIP procedure was used to detect regions in the LTR or within the HTLV genome (see Fig. 6 for locations). The PCR primer pair for region “a” that amplifies bp 41 to 298 of the U3 region was TRE-PH-S (41GAGTCATCGACCCAAAAGG59) and TRE-PH-AS (298TGCGCTTTTATAGACTCGGC279). The primer pair for region “b” (bp 1314 to 1412 of the gag/pol coding region) was #19 (1314AGCCCCCAGTTCATGCAGACC1334) and #20 (1412GAGGGAGGAGCATAGGTACTG1392). The primer pair for region “c” (bp 5011 to 5204 of exon 2 of tax/rex) was GP-S (5011CAGCGGTGGAAAGGTCC5027) and GP-AS (5204AAAGTAGGAAGAAAACATT5186). Primers used to amplify region “d” (bp 7314 to 7434 of exon 3 of tax/rex) were R1p28 (7314ATGTTCCACCCGCCT7328) and TR2-AS (7434GAGGCGAGGGATAAGGTAT7416).

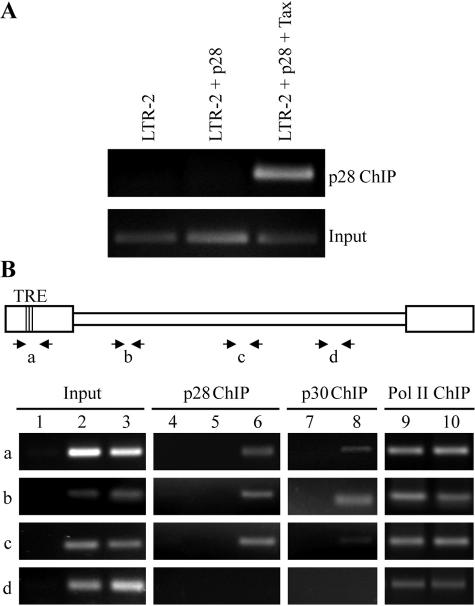

FIG. 6.

p28II associates with the HTLV-2 promoter, as well as downstream DNA sequences. (A) ChIP analysis reveals that p28II associates with the HTLV-2 promoter (LTR-2) but only in the presence of the transcription activator Tax-2, indicating that p28II associates only with a transcriptionally active promoter. Input, 10% of DNA prior to immunoprecipitation. (B) Schematic diagram of the HTLV-2 provirus with primer pairs used in the following ChIP are indicated. For exact location of primers, refer to Materials and Methods. TRE, three 21-bp repeats representing Tax response elements in the viral promoter. The ChIP assay was performed as described in the legend to panel A with antibodies specific for p28II, HTLV-1 p30II, or RNA polymerase II. PCR conditions for each primer pair were optimized to amplify a product in the linear range. Lanes 1 and 4, lysates from mock-transfected cells; lanes 2, 5, 7, and 9, lysates from cells expressing wtHTLV-2; lanes 3, 6, and 10, lysates from cells expressing wtHTLV-2 and p28II; lane 8, lysate from cells expressing wtHTLV-2 and p30II. Antibodies used in ChIP are indicated (top).

Each primer set was optimized for the amount of input DNA (1% of total lysate before immunoprecipitation) to give an amplified product in the linear range. Conditions for PCR were as follows: 95°C for 5 min, followed by 25 to 30 cycles, each consisting of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. A final extension at 72°C for 4 min was also performed. The number of cycles and the concentration of MgCl2 for PCR were optimized and were different for each primer set.

Coimmunoprecipitation assay.

293T cells transfected with 1 μg p28II, 1 μg Tax-2, or both were grown for 48 h and cells were lysed in profound lysis buffer (Pierce, Rockford, IL) on ice for 30 min. After centrifugation, ∼500 μg of cleared lysates was incubated overnight with 5 μl anti-AU1 antibody, 10 μl affinity ligand, and 20% (wt/vol) capture resin on Catch and Release Spin columns (Upstate Biotechnologies, Charlottesville, VA). The resin was washed five times with 1× wash buffer containing 1% NP-40 and 0.25% deoxycholic acid at pH 7.4. Immune complexes were eluted at room temperature with 2× SDS loading buffer, boiled, and separated by SDS-PAGE. Input samples represented 10% of the lysate prior to immunoprecipitation. Western blots were performed as above using antibodies against p28II, Tax-2, and RNA Pol II (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA).

RESULTS

HTLV-2 p28II inhibits viral Tax activity and protein production.

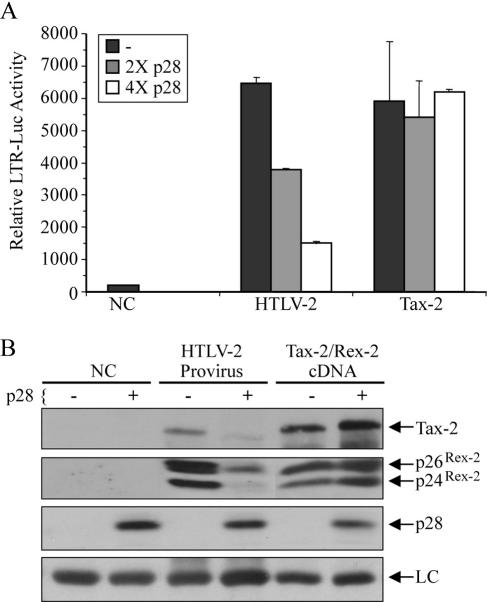

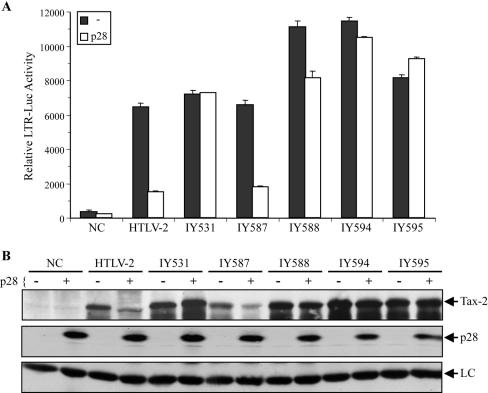

We recently showed that the HTLV-2 accessory gene product, p28II, is a nuclear protein that exhibits repressor activity on viral replication (61). We also showed that the inhibitory effects are exerted at the RNA level. More specifically, p28II binds to and retains tax/rex spliced mRNA in the nucleus. To compare the effects of p28II on tax/rex mRNA that is expressed from a CMV-Tax-2/Rex-2 cDNA expression plasmid (referred to hereafter as Tax-2), as opposed to the full-length provirus, HTLV-2 (Fig. 1 shows details of the constructs), we transfected 293T cells with either HTLV-2 or Tax-2 along with the Tax reporter, LTR-luciferase. Our data show that p28II inhibited Tax-2 activity only when Tax-2 was expressed from the proviral clone and not the cDNA expression plasmid (Fig. 2A). Identical results were obtained using a reporter construct containing a minimal promoter and two copies of the distal 21-bp repeat linked to luciferase (data not shown). The inability of p28II to inhibit Tax that is expressed from a cDNA could be attributed to overexpression in the case of the CMV expression plasmid compared to the native promoter in the HTLV-2 provirus. To rule out that the saturation of Tax activity causes the unresponsiveness to p28II, we transfected 293T cells with 0.4 μg of an empty vector (negative control or NC), 0.4 μg of HTLV-2 provirus, or 0.1 μg of Tax-2 cDNA plasmid, which led to similar levels of Tax activity on an LTR-luciferase reporter in the absence of p28II (Fig. 2A). Cotransfection of increasing amounts of p28II expression plasmid resulted in dose-dependent inhibition of Tax activity expressed from the HTLV-2 provirus but had no significant repression on Tax-2 activity expressed from the cDNA expression plasmid (Fig. 2A). Similar results were obtained with the p30II of HTLV-1 (data not shown).

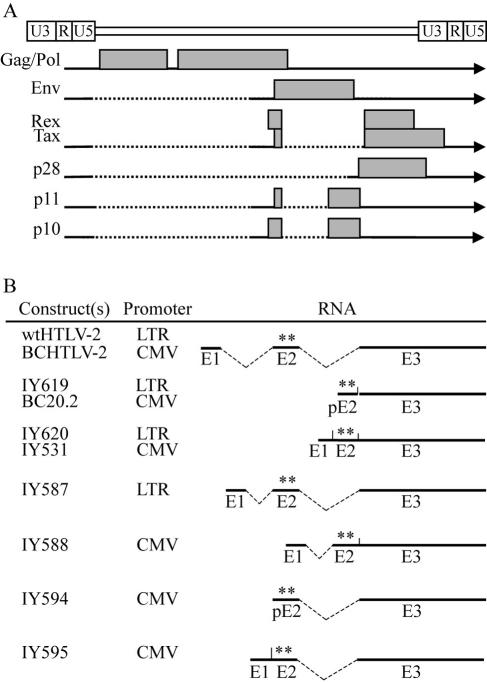

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagrams of the HTLV-2 genome and the different mRNAs (horizontal lines) and proteins (gray boxes) (A). Dashed lines represent introns that are spliced out. Below (panel B) are the different Tax expression plasmids used in this study. wtHTLV-2 and BCHTLV-2 are full-length proviral clones that express doubly spliced tax/rex mRNA. IY619 and Tax-2 (BC20.2) express the entire tax/rex coding sequence as a cDNA but lack the 5′UTR. IY620 and IY531 express full-length tax/rex cDNA, which includes the 5′UTR. IY587 is a proviral clone with truncated intron-1 (gag/pol sequences) that still expresses doubly spliced tax/rex mRNA. IY594 expresses tax/rex mRNA lacking the 5′UTR but contains intron-2. Both IY588 and IY595 express full-length tax/rex mRNA that contains a truncated intron-1 (gag/pol sequences) or intron-2 (env sequences), respectively. For more detailed description of the plasmids, see Materials and Methods. Plasmids wtHTLV-2, IY619, IY620, and IY587 express tax/rex mRNA from the HTLV-2 promoter (LTR), whereas plasmids BCHTLV-2, Tax-2, IY531, IY588, IY594, and IY595 utilize the CMV immediate early promoter. Asterisks represent Rex and Tax start codons.

FIG. 2.

HTLV-2 p28II inhibits Tax-2 and Rex-2 expression only when they are expressed from a full-length proviral clone. (A) A total of 0.4 μg of wtHTLV-2 plasmid or 0.1 μg of Tax-2 cDNA plasmid was transfected into 293T cells along with the LTR-luciferase reporter in the absence or presence of a 2× or 4× molar ratio of p28II expression plasmid. After 48 h of culture, cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured. Experiments were done in triplicate, and CMV-βgal was used to adjust for transfection efficiency. Negative control (NC), cells that are transfected with an empty vector. (B) The same lysates shown in panel A were separated on 4 to 12% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, followed by Western blotting using antibodies specific for Tax-2, Rex-2, p28II, or actin (LC). Rex-2 migrates as two bands, p24 (hypophosphorylated) and p26 (phosphorylated).

To validate that the inhibition of Tax activity was due to a reduction of Tax protein expression and not to a disruption of Tax function per se, we performed Western blot analysis of lysates extracted from the same cells that were transfected with the HTLV-2 provirus or Tax-2/Rex-2 cDNA in the presence or absence of exogenous p28II. In addition, since both Tax-2 and Rex-2 are expressed from the same doubly spliced mRNA, we measured Rex-2 protein levels to confirm that p28II inhibited tax/rex mRNA leading to a reduction in and therefore functional suppression of both proteins. As shown in Fig. 2B, both Tax-2 and Rex-2 proteins were significantly reduced in the presence of p28II but only if expressed in the context of the HTLV-2 provirus. These data corroborate the results of the functional activity of Tax and are consistent with the overall conclusion that p28II specifically inhibits tax/rex mRNA expressed from a provirus leading to repression of protein production.

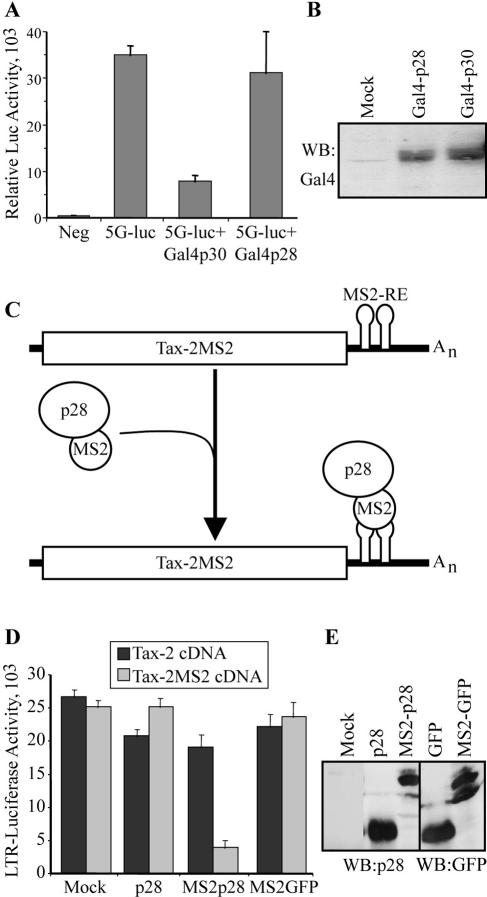

Tethering of p28II to the promoter or tax/rex mRNA identifies its intrinsic posttranscriptional repressor function.

HTLV-1 p30II has been established as both a transcriptional (1, 64, 65) and a posttranscriptional (44, 61) repressor of HTLV-1 gene expression. Therefore, to address potential mechanistic differences between p28II and p30II and to examine whether p28II has any transcriptional effects, p28II and p30II fusion proteins were generated to analyze their activity in tethering reporter assays. Using the Gal4 DNA binding domain, we targeted either Gal4-p28II or Gal4-p30II fusion proteins to a promoter containing five Gal4 binding sites upstream of the luciferase gene. As previously reported (65), Gal4-p30II repressed the expression of luciferase when tethered to the promoter. However, contrary to p30II, Gal4-p28II did not show any inhibitory effects on the same promoter, dispensing the possibility that p28II has transcriptional repressor activity (Fig. 3A). The lack of p28II-mediated transcriptional repression could not be attributed to inefficient expression of Gal4-p28II, which was expressed at levels similar to those of Gal4-p30II (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

p28II is a posttranscriptional repressor. (A) A Gal4 DNA binding domain fused with either p28II or p30II was transfected into 293T cells, together with the 5G-Luc reporter that contains a minimal promoter with five Gal4 binding sites upstream of a luciferase reporter. Experiments were done in triplicate, and error bars reflect standard deviations. (B) Gal4-p30II and Gal4-p28II were detected by immunoprecipitation using a Gal4-specific antibody. (C) Schematic diagram of tax-2MS2 mRNA with six MS2 response elements (MS2-RE) inserted after the Tax-2 termination codon and before the polyadenylation signal. The MS2-p28II fusion protein was targeted to the tax-2MS2 mRNA via the interaction between the MS2 protein and the MS2-RE. (D) 293T cells were transfected with LTR-luciferase reporter, together with a control, p28II, MS2-p28II, or MS2-GFP expression vector. Tax-2 was expressed from a Tax-2 or Tax-2MS2 cDNA expression plasmid. Transfections were performed in triplicate, and error bars reflect standard deviations. Tax activity was measured as luciferase units and averaged. (E). Expression of p28II, MS2-p28II, GFP, and MS2-GFP proteins was confirmed by Western blot analysis.

Our previous biochemical and functional studies indicated that p28II is a posttranscriptional regulator that inhibits Tax and Rex expression at the mRNA level. To couple the repression of p28II with its ability to associate with tax/rex mRNA (61), we tethered p28II to the mRNA using the previously established bacteriophage MS2 coat protein RNA interaction approach. A chimeric protein in which MS2 coat protein fused to the amino terminus of either p28II (MS2-p28II) or GFP (MS2-GFP) was generated (Fig. 3C). A reporter plasmid was generated containing MS2 binding sites at the 3′ of Tax-2 cDNA (Tax-2MS2) (Fig. 3C). To examine whether tethered p28II inhibited tax/rex mRNA, 293T cells were transfected with either Tax-2 or Tax-2MS2 cDNA, together with the Tax reporter plasmid (LTR-Luc) and different p28II constructs. As expected, the effects of p28II or the control chimeric protein MS2-GFP on Tax expressed from cDNA were negligible. Conversely, only Tax expressed from a cDNA containing MS2 binding sites was inhibited by MS2-p28II, indicating that targeting p28II to the mRNA led to inhibition of Tax activity (Fig. 3D). To control for expression of the different fusion proteins, Western blot analysis performed on lysates from the transfected cells indicated that all the proteins were expressed (Fig. 3E).

The 5′UTR and splicing of tax/rex mRNA do not contribute to p28II-mediated inhibition.

In an effort to understand the mechanism of the p28II-mediated inhibition and its differential effects on expression from the provirus versus cDNA, we next focused on the mRNA itself. As highlighted in the panel of constructs shown in Fig. 1, there are three differences between the mRNA expressed from the HTLV-2 provirus and the Tax cDNA expression plasmid. The tax/rex mRNA expressed from the provirus contains a 5′UTR and is doubly spliced. Both features are excluded from mRNA expressed from the cDNA expression vector. Furthermore, expression of the tax/rex mRNA from the provirus is driven by the HTLV-2 natural promoter that is present in the LTR, whereas expression of the Tax-2 cDNA is directed by the CMV immediate early promoter.

Since data indicate that sequences in the UTR of genes can regulate mRNA processing at different steps ranging from overall stability (41, 59) to translational efficiency (23, 46), we examined whether the 5′UTR could play a role in recruiting p28II to tax/rex mRNA leading to its inhibition. A cDNA construct expressing full-length tax/rex mRNA that includes the 5′UTR (IY531) (Fig. 1) was generated and tested for susceptibility to inhibition by p28II. 293T cells were transfected with either HTLV-2 or IY531 in the presence or absence of p28II. Tax activity (Fig. 4A) and protein levels (Fig. 4B) were then measured. The results show that the addition of the 5′UTR to the Tax cDNA did not result in p28II-mediated inhibition of Tax activity.

FIG. 4.

Intron sequences-splicing and 5′UTR are not required for p28II-mediated inhibition of Tax activity. (A) A total of 0.4 μg of wtHTLV-2 and IY587 plasmids or 0.1 μg of the indicated Tax-2 cDNA plasmids was transfected into 293T cells, along with the LTR-luciferase reporter in the absence or presence of a 4× molar ratio of p28II expression plasmid. After 48 h of culture, cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured. Experiments were done in triplicate, and error bars reflect standard deviations. CMV-βgal was used to adjust for transfection efficiency. Negative control (NC), cells that are transfected with empty vector. p28II inhibited Tax-2 activity that was expressed from both wtHTLV-2 and IY587, indicating that truncating intron-1 does not influence p28II-mediated inhibition or Tax-2 expression. All cDNA expression plasmids showed minimal or no inhibition by p28II. (B) The same lysates shown in panel A were separated on 4 to 12% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane, followed by Western blotting with antibodies specific for Tax-2, p28II, or actin (LC). Reduction of Tax protein correlates with loss of Tax activity shown in panel A.

Several studies demonstrate that pre-mRNA splicing imprints the mRNA in the nucleus with a range of proteins needed for later processes such as export, translation, and stability (7, 12, 37, 39, 63). In light of our previous results showing that the inhibitory effect of p28II is dependent on its ability to bind to the spliced tax/rex mRNA and retain it in the nucleus (61), we sought to determine if the splicing process and subsequently loading of splicing factors and/or the exon junction complex might recruit p28II to tax/rex mRNA. We generated a panel of constructs that reinserted intron-1 or intron-2 into the tax/rex cDNA plasmids with or without the 5′UTR (Fig. 1). To simplify our plasmid vector and to test whether sequences in intron-1 are important for p28II-mediated inhibition, we generated a construct containing a large deletion in the gag/pol ORF. Truncation of the intron did not have a detrimental effect on Tax activity itself or the ability of p28II to inhibit Tax activity (IY587) (Fig. 4). Further analysis of the cDNA plasmids containing introns indicated that splicing of neither intron-1 nor intron-2 is necessary or sufficient for p28II-mediated inhibition, since none of these constructs was significantly responsive to p28II (Fig. 4A, compare IY588, IY594, and IY595 to HTLV-2 or IY587). Western blot analysis results were consistent with the Tax functional assay, revealing a p28II-mediated reduction in Tax protein but only if Tax was expressed from HTLV-2 and IY587 (Fig. 4B). Taking the data together, we conclude that recruitment of p28II to tax/rex mRNA and repression of Tax/Rex activity are not dependent on 5′UTR sequences, intron sequences, the loading of splicing factors, and/or splicing itself.

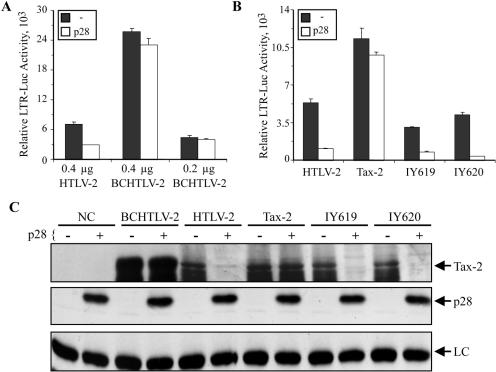

Inhibition of tax/rex mRNA by p28II is coupled to the HTLV-2 promoter.

To determine whether the promoter from which tax/rex mRNA is expressed is directly correlated to p28II-mediated inhibition, we replaced the native HTLV-2 core promoter by a CMV immediate early promoter in the context of the provirus (BCHTLV-2) (Fig. 1). Tax activity expressed from BCHTLV-2 was not repressed by p28II compared to the wild-type provirus (Fig. 5A). Since expression from a CMV promoter is more efficient than that from HTLV-2, two concentrations of BCHTLV-2 were tested to rule out the possibility that resistance to p28II inhibition was due to high expression levels and saturation. Furthermore, to examine the possible role of the HTLV-2 promoter on the repressive activity of p28II, we replaced the CMV promoter in BC20.2 and IY531 by the HTLV-2 promoter generating IY619 and IY620, respectively (Fig. 1). As shown in Fig. 5B, p28II had the capacity to inhibit Tax activity when Tax was expressed from constructs containing the native HTLV-2 promoter (HTLV-2, IY619, and IY620) but not the CMV promoter. Western blot analysis results were consistent with the Tax functional assay, revealing a p28II-mediated reduction in Tax expressed from only HTLV-2, IY619, and IY620 (Fig. 5C). Taken together, these results indicated that the recruitment of p28II to tax/rex mRNA and repression of Tax/Rex activity were dependent on the HTLV-2 promoter, specifically, the HTLV-2 U3 region.

FIG. 5.

p28II-mediated inhibition directly correlates with Tax expression in the context of the native HTLV-2 promoter (LTR). (A) A total of 0.4 μg of wtHTLV-2 or 0.4 or 0.2 μg of BCHTLV-2 was transfected into 293T cells along with LTR-luciferase in the absence or presence of a 4× molar ratio of p28II expression plasmid. After 48 h of culture, cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured. Experiments were done in triplicate, and error bars reflect standard deviations. CMV-βgal was used to adjust for transfection efficiency. p28II consistently inhibits Tax-2 activity when expressed from wtHTLV-2 but not BCHTLV-2. (B) Expression of Tax-2 from cDNA with (IY620) or without (IY619) 5′UTR but under the control of the HTLV-2 promoter reverses the resistance to inhibition by p28II that is observed with the Tax-2 CMV expression plasmid. (C) Lysates shown in panels A and B were separated on 4 to 12% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, followed by Western blotting with antibodies specific for Tax-2, p28II, or actin (LC). Reduction of Tax protein correlates with loss of Tax activity shown in panels A and B.

HTLV-2 p28II and HTLV-1 p30II are recruited to the viral promoter and associate with transcription elongation.

To investigate whether the correlation between the inhibition of Tax/Rex activity by p28II and the HTLV-2 promoter is due to a direct association, we used the ChIP approach on cells transfected with a construct expressing HTLV-2 LTR-luciferase in the presence or absence of p28II. Since efficient transcription from the viral LTR requires Tax, we also transfected Tax to determine whether an association, if any, is dependent on a transcriptionally active promoter. Cross-linked and sonicated extracts prepared from transfected cells were immunoprecipitated using an antibody specific for p28II-AU1. Input DNA that was not subjected to immunoprecipitation as well as coprecipitated DNA fragments were amplified by PCR using a primer pair specific for the viral promoter region. More specifically, the primers span all three TREs that are present in the U3 region of LTR-2. Figure 6A shows that p28II is clearly associated with the HTLV-2 viral promoter in a Tax-dependent manner, suggesting that the recruitment of p28II occurs during transcription.

To define the role of this cotranscriptional recruitment in sequestering p28II to the newly transcribed mRNA, we examined the association of p28II with different regions of the 9-kb HTLV-2 genome by ChIP analysis. Primer pair “a” detects the promoter region, pair “b” detects gag sequences, pair “c” amplifies exon 2 of tax/rex sequences, and pair “d” detects sequences in tax/rex exon 3 (Fig. 6B). To validate our experimental conditions, we also analyzed two other proteins whose distribution on the HTLV-2 genome is known or can be anticipated. RNA polymerase II (Pol II) is known to be evenly distributed over the promoter region, coding region, and 3′UTR of actively transcribed genes (48, 62). HTLV-1 p30II, the functional homologue for HTLV-2 p28II, has a proposed role in both transcriptional (1, 64, 65) and posttranscriptional (44, 61) regulation and would be expected to be found at the promoter.

As previously shown (62), Pol II association was detected at all regions of the viral genome (Fig. 6B). The distribution of p28II and p30II was analyzed using the monoclonal antibodies AU1 (for p28II) and HA (for p30II). Interestingly, these proteins showed very similar distribution patterns over the HTLV-2 genome with positive signal for regions “a,” “b,” and “c,” whereas no clear association was detected for region “d” (Fig. 6B). These profiles are consistent with the hypothesis that p28II and p30II are recruited to the tax/rex mRNA at the transcription level and that the lack of binding or cross-linking at the 3′ coding region may reflect the redistribution of p28II and p30II from the transcriptional machinery to the newly transcribed and/or processed mRNA.

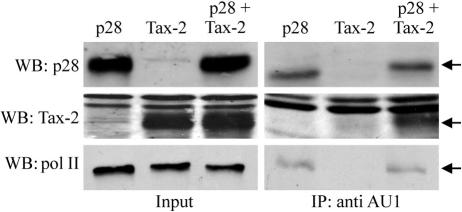

p28II interacts with Tax-2 and components of the transcriptional machinery.

The data above indicated that p28II associates with a transcriptionally active HTLV-2 promoter, which leads to its recruitment to the tax/rex mRNA. To further verify the interaction between p28II and components of the transcriptional machinery in intact cells, 293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing p28II, Tax-2, or both, followed by immunoprecipitation of p28II complexes. Proteins associated with p28II were analyzed by SDS-PAGE; individual proteins were identified by Western blot analysis. Results from representative Western blots in Fig. 7 confirmed that the monoclonal AU1 antibody efficiently immunoprecipitated p28II-AU1, which was detected by using a rabbit polyclonal antibody to p28II. Importantly, with cells that coexpressed both p28II and Tax-2, we were able to coimmunoprecipitate Tax-2 along with p28II. Nonspecific binding of Tax-2 to the beads or the antibody could not account for this result because Tax was not immunoprecipitated in cells that did not express p28II. Likewise, we were able to immunoprecipitate endogenous RNA Pol II with p28II. These results demonstrated that p28II was able to associate with components of the transcriptional machinery in mammalian cells.

FIG. 7.

p28II associates with components of the transcription machinery. Immunoprecipitation using AU1 antibody was performed on 293T cells transfected with p28II-AU1, Tax-2, or both. Immune complexes were resolved by SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blot analysis using Tax-2-, Pol II-, or p28II-specific antibodies. Prior to immunoprecipitation, 10% of lysates were saved (Input) and blotted as above.

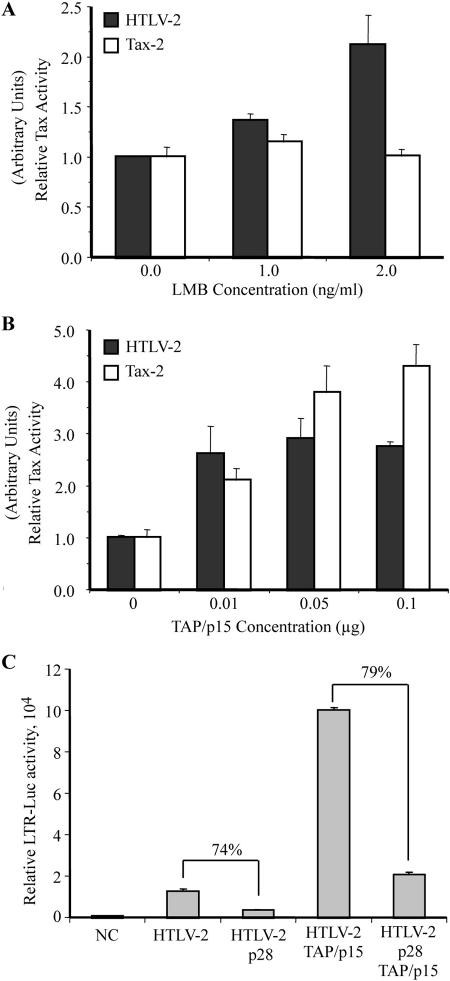

Inhibition of tax/rex mRNA by p28II may involve the TAP/p15 pathway.

Thus far, our data along with our previous findings suggested two nonexclusive possibilities for the mechanism through which p28II inhibits tax/rex mRNA: p28II may actively retain the mRNA in the nucleus, or p28II may inhibit export of the mRNA by interfering with its export pathway. To define the pathway used by tax/rex mRNA for nucleocytoplasmic transport, we examined the contribution of two major pathways on Tax expression. The CRM1 pathway is utilized by several viral mRNAs, including HTLV unspliced and incompletely spliced gag/pol and env mRNA for transport to the cytoplasm (60). Conversely, the majority of mammalian spliced mRNAs utilize the TAP/p15 export pathway (13, 50, 51). The specific CRM1 inhibitor, leptomycin B (LMB), was used to test whether CRM1 is involved in tax/rex mRNA export. LMB had no inhibitory effects on Tax activity when expressed from a provirus or a cDNA expression vector (Fig. 8A). In fact, there was a slight enhancement of Tax activity when expressed from a provirus. We attributed that enhancement to blockage of gag/pol and env mRNA export and redistribution of the viral mRNA pools to favor splicing. We next tested the effects of exogenous TAP/p15 on Tax activity in transfected 293T cells. Consistent with the hypothesis that tax/rex mRNA utilizes TAP/p15 for transport to the cytoplasm, all three concentrations of TAP/p15 enhanced Tax activity (Fig. 8B). Last, we examined whether p28II was able to repress Tax expression in the presence of exogenous TAP/p15. Consistent with our previous data, p28II caused 70 to 80% inhibition of Tax activity when expressed from a provirus (Fig. 8C). While overexpression of TAP/p15 significantly enhanced Tax activity, p28II resulted in a 79% inhibition of that activity at the dose used (Fig. 8C). These data indicated that p28II repression occurs upstream of the TAP/p15 export pathway.

FIG. 8.

p28II overrides the TAP/p15 export pathway. (A) Expression of Tax-2 from full-length provirus (HTLV-2) or cDNA plasmid (Tax-2) was tested in the absence or presence of the CRM1 specific inhibitor LMB. (B) Expression of Tax-2 from HTLV-2 or Tax-2 plasmid was tested in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of TAP and p15 expression plasmids. (A and B) Tax-2 expression was indirectly measured using the LTR-luciferase reporter. (C) p28II-mediated inhibition of Tax-2 that is expressed from HTLV-2 was tested in the absence or presence of 10 ng of TAP and p15. The percent inhibition is indicated in each case. All experiments were done in triplicate, and error bars reflect standard deviations. CMV-βgal was used to adjust for transfection efficiency.

DISCUSSION

The HTLV-2 p28II accessory protein is a potent repressor of viral gene expression by specifically interacting with and retaining tax/rex mRNA in the nucleus (61) leading to a decrease in protein production. Tax and Rex are critical proteins that play essential roles in HTLV replication. Tax is the main transcriptional regulator of the HTLV promoter, which is present in the 5′LTR and drives expression of all viral genes (15). Rex is a posttranscriptional regulator that facilitates the cytoplasmic expression of unspliced and incompletely spliced viral mRNAs (60). Thus, by lowering Tax and Rex expression, p28II can suppress viral replication (61), leading to a state of viral latency that is suggested to be critical for viral persistence in vivo. Consistent with this principle, an infectious molecular clone of HTLV-2 that is deficient for p28II is unable to spread and persist in a rabbit model of HTLV infection (I. Younis et al., unpublished data).

In this report, we have identified the mechanism by which p28II is selectively recruited to tax/rex mRNA. We previously showed that the inhibitory effects of p28II were restricted to tax/rex mRNA expressed from a full-length provirus and not a cDNA expression plasmid (Fig. 2) (61). Putative candidates that may aid in recruiting p28II to the former mRNA but not the latter include 5′UTR, splicing, or the promoter context. Thus, we generated a panel of Tax expression plasmids to test for the contribution of these variables separately or in combination. Our data indicated that neither the 5′UTR nor splicing of the pre-mRNA was sufficient to make tax/rex mRNA a substrate for p28II repression (Fig. 4). Conversely, we showed a positive correlation between expression from the native HTLV promoter (LTR) and p28II-mediated inhibition of Tax activity (Fig. 5). Replacing the LTR in a proviral clone by a CMV promoter was sufficient to block the repressive effects of p28II. Moreover, switching the CMV promoter with the LTR in a previously resistant Tax cDNA expression plasmid rendered tax mRNA completely susceptible to inhibition by p28II. These data, together with our previous report (61), identify two parameters that are necessary for p28II activity: Tax-dependent transcription from the HTLV-2 promoter and a unique element on tax/rex mRNA, possibly an exon-2-exon-3 junction.

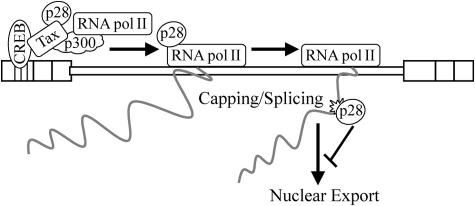

In recent years, considerable evidence has accumulated to support the concept that transcription directed by RNA Pol II and downstream mRNA processing events such as splicing, export, and polyadenylation are functionally coupled (25). In this study, we confirmed that p28II is not a transcriptional regulator (Fig. 3) but is recruited cotranscriptionally to the promoter in a Tax-dependent manner. Chromatin immunoprecipitation was used to show the association profiles of p28II, its HTLV-1 homologue p30II, and Pol II with a transcriptionally active HTLV-2 genome. Our results showed an association between p28II and p30II with the promoter region, as well as the 5′ end and middle of the coding region of HTLV-2. This observation, together with the loss of association at the 3′ end of the coding region, supports the conclusion that these proteins not only are recruited to the promoter but also are components of the transcription-elongation complex until their response element on the newly transcribed tax/rex mRNA is generated (Fig. 6 and 9). Interestingly, the similar association profiles of p28II and p30II suggest that these two proteins utilize a similar mechanism for their recruitment to their target mRNAs. It is worth noting, however, that although p28II has negligible transcriptional activity, p30II has the capacity to modulate transcription of HTLV-1 differentially, due to its interaction with the transcriptional coactivator p300 (65). Moreover, p30II has recently been shown to interact with and stabilize the Myc/TIP60 transcription complexes that assemble on Myc responsive promoters such as cyclin D2, leading to an enhanced Myc-transforming potential (1). Conversely, p28II does not interact with p300 (data not shown) but physically associates with Tax-2 and Pol II, providing more evidence that it is recruited at the level of transcription and becomes a component of the elongation complex.

FIG. 9.

A model for the mechanism of action of p28II. After recruitment to the HTLV-2 promoter in a Tax-dependent manner, p28II associates with RNA Pol II and moves with the transcription elongation machinery. As the RNA is being synthesized, capped, and spliced, a novel mRNA element is generated (possibly the exon-2-exon-3 junction only present in tax/rex mRNA) and is recognized by p28II, which translocates to the mRNA, leading to its retention in the nucleus.

Mammalian mRNAs utilize at least two nuclear export receptors to achieve export to the cytoplasm including CRM1 and TAP/p15. Retroviruses, including HTLV, depend on these pathways for the export of their own mRNA (13). For example, both HIV and HTLV require the export and cytoplasmic expression of unspliced and incompletely spliced mRNAs that encode structural and enzymatic proteins. HIV Rev and HTLV Rex are adaptor proteins that provide access to the CRM1 pathway to export such mRNAs (49, 60). Mason-Pfizer monkey virus, on the other hand, recruits TAP/p15 to a specific sequence on its unspliced mRNA (constitutive transport element) to allow transport to the cytoplasm (5, 6). Since our previous study indicated that p28II interferes with the nucleocytoplasmic export of tax/rex mRNA, we examined the contribution of CRM1 and TAP/p15 to this process. Our data suggested that while CRM1 did not contribute to Tax expression and activity, exogenous TAP/p15 significantly enhanced Tax activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 8). When p28II was transfected into cells along with TAP/p15, we observed that the suppression of Tax activity was sustained. This possibly could be attributed to p28II overriding or blocking the TAP/p15 pathway. The fact that p28II did not show complete inhibition of Tax activity in the presence of TAP/p15 could be due to some TAP-dependent rescue of tax/rex mRNA export. In either case, there appeared to be cross talk between p28II and TAP/p15 that needs to be analyzed further. Another possible explanation for the ability of p28II to inhibit Tax expression in the presence of exogenous TAP/p15 is based on previous reports indicating that in 293T cells, Tap/p15 complexes are likely to play an important role in translational regulation beyond their previously proposed function as RNA export receptors. More specifically, Tap/p15 augments protein expression from mRNAs that have already been exported from the nucleus by enhancing polyribosome association and translation of these mRNAs (27, 29). Thus, if TAP/p15-mediated enhancement of Tax expression in 293T cells is due to their translational effects (i.e., requires the presence of the mRNA in the cytoplasm), p28II would still be able to block this enhancement simply by retaining the mRNA in the nucleus, making it unavailable to TAP/p15.

Collectively, our findings suggest that Tax-mediated transcription of the HTLV LTR is a process that serves not only to drive the expression of viral genes, but also to recruit a negative factor that suppresses the expression of two of the major positive regulators of HTLV expression, leading to a complicated but tightly regulated feedback loop. Such regulation might hold the key for latency and evasion of the immune response in vivo. We propose a model in which p28II and p30II, two suppressors of gene expression, are recruited to transcriptionally active HTLV promoters in a Tax-dependent manner. Their interaction with RNA Pol II helps position them close to the newly transcribed and processed mRNA substrate, leading to highly efficient recognition and eventually to suppression of gene expression. This model suggests that the functional coupling between transcription and mRNA export could be utilized to promote as well as suppress gene expression (Fig. 9). A better understanding of the role of the accessory proteins is critical to expand our knowledge not only of their contribution to basic cellular biology and virology, but also for virus-associated disease progression and therapeutic development.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tim Vojt for preparation of the figures and Kate Hayes for editorial comments.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (CA100730) to P.L.G. and K.B.-L.

REFERENCES

- 1.Awasthi, S., A. Sharma, K. Wong, J. Zhang, E. F. Matlock, L. Rogers, P. Motloch, S. Takemoto, H. Taguchi, M. D. Cole, B. Luscher, O. Dittrich, H. Tagami, Y. Nakatani, M. McGee, A. M. Girard, L. Gaughan, C. N. Robson, R. J. Monnat, Jr., and R. Harrod. 2005. A human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 enhancer of Myc transforming potential stabilizes Myc-TIP60 transcriptional interactions. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:6178-6198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartoe, J. T., B. Albrecht, N. D. Collins, M. D. Robek, L. Ratner, P. L. Green, and M. D. Lairmore. 2000. Functional role of pX open reading frame II of human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 in maintenance of viral loads in vivo. J. Virol. 74:1094-1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bentley, D. 1999. Coupling RNA polymerase II transcription with pre-mRNA processing. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 11:347-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brady, J., K. T. Jeang, J. Durall, and G. Khoury. 1987. Identification of the p40x-responsive regulatory sequences within the human T-cell leukemia virus type I long terminal repeat. J. Virol. 61:2175-2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braun, I. C., A. Herold, M. Rode, E. Conti, and E. Izaurralde. 2001. Overexpression of TAP/p15 heterodimers bypasses nuclear retention and stimulates nuclear mRNA export. J. Biol. Chem. 276:20536-20543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braun, I. C., E. Rohrbach, C. Schmitt, and E. Izaurralde. 1999. TAP binds to the constitutive transport element (CTE) through a novel RNA-binding motif that is sufficient to promote CTE-dependent RNA export from the nucleus. EMBO J. 18:1953-1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter, M. S., S. Li, and M. F. Wilkinson. 1996. A splicing-dependent regulatory mechanism that detects translation signals. EMBO J. 15:5965-5975. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, I. Y., J. McLaughlin, J. C. Gasson, S. C. Clark, and D. W. Golde. 1983. Molecular characterization of genome of a novel human T-cell leukaemia virus. Nature 305:502-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ciminale, V., G. N. Pavlakis, D. Derse, C. P. Cunningham, and B. K. Felber. 1992. Complex splicing in the human T-cell leukemia virus (HTLV) family of retroviruses: novel mRNAs and proteins produced by HTLV type I. J. Virol. 66:1737-1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cockerell, G. L., J. Rovank, P. L. Green, and I. S. Y. Chen. 1996. A deletion in the proximal untranslated pX region of human T-cell leukemia virus type II decreases viral replication but not infectivity in vivo. Blood 87:1030-1035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins, N. D., G. C. Newbound, B. Albrecht, J. Beard, L. Ratner, and M. D. Lairmore. 1998. Selective ablation of human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 p12I reduces viral infectivity in vivo. Blood 91:4701-4707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cullen, B. R. 2000. Connections between the processing and nuclear export of mRNA: evidence for an export license? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:4-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cullen, B. R. 2003. Nuclear mRNA export: insights from virology. Trends Biochem. Sci. 28:419-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Derse, D., J. Mikovits, and F. Ruscetti. 1997. X-I and X-II open reading frames of HTLV-I are not required for virus replication or for immortalization of primary T-cells in vitro. Virology 237:123-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felber, B. K., H. Paskalis, C. Kleinman-Ewing, F. Wong-Staal, and G. N. Pavlakis. 1985. The pX protein of HTLV-I is a transcriptional activator of its long terminal repeats. Science 229:675-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fong, N., and D. L. Bentley. 2001. Capping, splicing, and 3′ processing are independently stimulated by RNA polymerase II: different functions for different segments of the CTD. Genes Dev. 15:1783-1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Georges, S. A., H. A. Giebler, P. A. Cole, K. Luger, P. J. Laybourn, and J. K. Nyborg. 2003. Tax recruitment of CBP/p300, via the KIX domain, reveals a potent requirement for acetyltransferase activity that is chromatin dependent and histone tail independent. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:3392-3404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gessain, A., J. C. Vernant, L. Maurs, F. Barin, O. Gout, A. Calender, and G. de The. 1985. Antibodies to human T-lymphotropic virus type-1 in patients with tropical spastic paraparesis. Lancet ii:407-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giebler, H. A., J. E. Loring, K. Van Orden, M. Colgin, J. E. Garrus, K. W. Escudero, A. Brauweiler, and J. K. Nyborg. 1997. Anchoring of CREB binding protein to the human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 promoter: a molecular mechanism of Tax transactivation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:5156-5164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green, P. L., and I. S. Y. Chen. 2001. Human T-cell leukemia virus types 1 and 2, p. 1941-1969. In D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, D. E. Griffin, R. A. Lamb, M. A. Martin, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 21.Green, P. L., T. M. Ross, I. S. Y. Chen, and S. Pettiford. 1995. Hum. T-cell leukemia virus type II nucleotide sequences between env and the last exon of tax/rex are not required for viral replication or cellular transformation. J. Virol. 69:387-394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grossman, W. J., J. T. Kimata, F. H. Wong, M. Zutter, T. J. Ley, and L. Ratner. 1995. Development of leukemia in mice transgenic for the tax gene of human T-cell leukemia virus type I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:1057-1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hesketh, J. 2004. 3′-untranslated regions are important in mRNA localization and translation: lessons from selenium and metallothionein. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 32:990-993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hinuma, Y., K. Nagata, M. Hanaoka, M. Nakai, T. Matsumoto, K.-I. Kinoshita, S. Shirakawa, and I. Miyoshi. 1981. Adult T-cell leukemia: antigen in an ATL cell line and detection of antibodies to the antigen in human sera. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 78:6476-6480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirose, Y., and J. L. Manley. 2000. RNA polymerase II and the integration of nuclear events. Genes Dev. 14:1415-1429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hjelle, B., O. Appenzeller, R. Mills, S. Alexander, N. Torrez-Martinez, R. Jahnke, and G. Ross. 1992. Chronic neurodegenerative disease associated with HTLV-II infection. Lancet 339:645-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hull, S., and K. Boris-Lawrie. 2003. Analysis of synergy between divergent simple retrovirus posttranscriptional control elements. Virology 317:146-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeang, K.-T., I. Boros, J. Brady, M. Radonovich, and G. Khoury. 1988. Characterization of cellular factors that interact with the human T-cell leukemia virus type I p40x-responsive 21-base-pair sequence. J. Virol. 62:4499-4509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jin, L., B. W. Guzik, Y. C. Bor, D. Rekosh, and M. L. Hammarskjold. 2003. Tap and NXT promote translation of unspliced mRNA. Genes Dev. 17:3075-3086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kimzey, A. L., and W. S. Dynan. 1998. Specific regions of contact between human T-cell leukemia virus type I Tax protein and DNA identified by photocross-linking. J. Biol. Chem. 273:13768-13775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koralnik, I. J., A. Gessain, M. E. Klotman, A. Lo Monico, Z. N. Berneman, and G. Franchini. 1992. Protein isoforms encoded by the pX region of human T-cell leukemia/lymphotropic virus type I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:8813-8817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwok, R. P. S., M. E. Laurance, J. R. Lundblad, P. S. Goldman, H.-M. Shih, L. M. Connor, S. J. Marriott, and R. H. Goodman. 1996. Control of cAMP-regulated enhancers by the viral transactivator Tax through CREB and the co-activator CBP. Nature 380:642-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lemasson, I., N. J. Polakowski, P. J. Laybourn, and J. K. Nyborg. 2004. Transcription regulatory complexes bind the human T-cell leukemia virus 5′ and 3′ long terminal repeats to control gene expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:6117-6126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lenzmeier, B. A., E. E. Baird, P. B. Dervan, and J. K. Nyborg. 1999. The tax protein-DNA interaction is essential for HTLV-I transactivation in vitro. J. Mol. Biol. 291:731-744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu, H., C. A. Pise-Masison, T. M. Fletcher, R. L. Schiltz, A. K. Nagaich, M. Radonovich, G. Hager, P. A. Cole, and J. N. Brady. 2002. Acetylation of nucleosomal histones by p300 facilitates transcription from tax-responsive human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 chromatin template. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:4450-4462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lundblad, J. R., R. P. Kwok, M. E. Laurance, M. S. Huang, J. P. Richards, R. G. Brennan, and R. H. Goodman. 1998. The human T-cell leukemia virus-1 transcriptional activator Tax enhances cAMP-responsive element-binding protein (CREB) binding activity through interactions with the DNA minor groove. J. Biol. Chem. 273:19251-19259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luo, M. J., and R. Reed. 1999. Splicing is required for rapid and efficient mRNA export in metazoans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:14937-14942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maniatis, T., and R. Reed. 2002. An extensive network of coupling among gene expression machines. Nature 416:499-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matsumoto, K., K. M. Wassarman, and A. P. Wolffe. 1998. Nuclear history of a pre-mRNA determines the translational activity of cytoplasmic mRNA. EMBO J. 17:2107-2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCracken, S., N. Fong, K. Yankulov, S. Ballantyne, G. Pan, J. Greenblatt, S. D. Patterson, M. Wickens, and D. L. Bentley. 1997. The C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II couples mRNA processing to transcription. Nature 385:357-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meng, Z., P. H. King, L. B. Nabors, N. L. Jackson, C. Y. Chen, P. D. Emanuel, and S. W. Blume. 2005. The ELAV RNA-stability factor HuR binds the 5′-untranslated region of the human IGF-IR transcript and differentially represses cap-dependent and IRES-mediated translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:2962-2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Michael, B., A. M. Nair, H. Hiraragi, L. Shen, G. Feuer, K. Boris-Lawrie, and M. D. Lairmore. 2004. Human T lymphotropic virus type 1 p30II alters cellular gene expression to selectively enhance signaling pathways that activate T lymphocytes. Retrovirology 1:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nerenberg, M., S. M. Hinrichs, R. K. Reynolds, G. Khoury, and G. Jay. 1987. The tat gene of human T-lymphotrophic virus type I induces mesenchymal tumors in transgenic mice. Science 237:1324-1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nicot, C., J. M. Dundr, J. R. Johnson, J. R. Fullen, N. Alonzo, R. Fukumoto, G. L. Princler, D. Derse, T. Misteli, and G. Franchini. 2004. HTLV-1-encoded p30II is a post-transcriptional negative regulator of viral replication. Nat. Med. 10:197-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Osame, M., K. Usuku, S. Izumo, N. Ijichi, H. Amitani, A. Igata, M. Matsumoto, and M. Tara. 1986. HTLV-I associated myelopathy, a new clinical entity. Lancet i:1031-1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pickering, B. M., and A. E. Willis. 2005. The implications of structured 5′ untranslated regions on translation and disease. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 16:39-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Poiesz, B. J., F. W. Ruscetti, A. F. Gazdar, P. A. Bunn, J. D. Minna, and R. C. Gallo. 1980. Detection and isolation of type C retrovirus particles from fresh and cultured lymphocytes of a patient with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 77:7415-7419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pokholok, D. K., N. M. Hannett, and R. A. Young. 2002. Exchange of RNA polymerase II initiation and elongation factors during gene expression in vivo. Mol. Cell 9:799-809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pollard, V. W., and M. H. Malim. 1998. The HIV-1 Rev protein. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 52:491-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reed, R. 2003. Coupling transcription, splicing and mRNA export. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15:326-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reed, R., and E. Hurt. 2002. A conserved mRNA export machinery coupled to pre-mRNA splicing. Cell 108:523-531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Robek, M., and L. Ratner. 2000. Immortalization of T-lymphocytes by human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 is independent of the Tax-CBP/p300 interaction. J. Virol. 74:11988-11992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robek, M., F. Wong, and L. Ratner. 1998. Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 pX-I and pX-II open reading frames are dispensable for the immortalization of primary lymphocytes. J. Virol. 72:4458-4462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosenblatt, J. D., J. V. Giorgi, D. W. Golde, J. B. Ezra, A. Wu, C. D. Winberg, J. Glaspy, W. Wachsman, and I. S. Chen. 1988. Integrated human T-cell leukemia virus II genome in CD8+ T cells from a patient with “atypical” hairy cell leukemia: evidence for distinct T and B cell lymphoproliferative disorders. Blood 71:363-369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rosenblatt, J. D., D. W. Golde, W. Wachsman, A. Jacobs, G. Schmidt, S. Quan, J. C. Gasson, and I. S. Y. Chen. 1986. A second HTLV-II isolate associated with atypical hairy-cell leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 315:372-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ross, T. M., M. Narayan, Z.-Y. Fang, A. C. Minella, and P. L. Green. 2000. Human T-cell leukemia virus type 2 Tax mutants that selectively abrogate NFκB or CREB/ATF activation fail to transform primary human T cells. J. Virol. 74:2655-2662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seiki, M., R. Eddy, T. B. Shows, and M. Yoshida. 1984. Nonspecific integration of the HTLV provirus genome into adult T-cell leukaemia cells. Nature 309:640-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Silverman, L. R., A. J. Phipps, A. Montgomery, L. Ratner, and M. D. Lairmore. 2004. Human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 open reading frame II-encoded p30II is required for in vivo replication: evidence of in vivo reversion. J. Virol. 78:3837-3845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Westmark, C. J., V. B. Bartleson, and J. S. Malter. 2005. RhoB mRNA is stabilized by HuR after UV light. Oncogene 24:502-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Younis, I., and P. L. Green. 2005. The human T-cell leukemia virus Rex protein. Front. Biosci. 10:431-445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Younis, I., L. Khair, M. Dundr, M. D. Lairmore, G. Franchini, and P. L. Green. 2004. Repression of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 and 2 replication by a viral mRNA-encoded posttranscriptional regulator. J. Virol. 78:11077-11083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zenklusen, D., P. Vinciguerra, J. C. Wyss, and F. Stutz. 2002. Stable mRNP formation and export require cotranscriptional recruitment of the mRNA export factors Yra1p and Sub2p by Hpr1p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:8241-8253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang, J., X. Sun, Y. Qian, and L. E. Maquat. 1998. Intron function in the nonsense-mediated decay of beta-globin mRNA: indications that pre-mRNA splicing in the nucleus can influence mRNA translation in the cytoplasm. RNA 4:801-815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang, W., J. W. Nisbet, B. Albrecht, W. Ding, F. Kashanchi, J. T. Bartoe, and M. D. Lairmore. 2001. Human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 p30II regulates gene transcription by binding CREB binding protein/p300. J. Virol. 75:9885-9895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang, W., J. W. Nisbet, J. T. Bartoe, W. Ding, and M. D. Lairmore. 2000. Human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 p30II functions as a transcription factor and differentially modulates CREB-responsive promoters. J. Virol. 74:11270-11277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]