Abstract

In many organisms, the formation of asparaginyl-tRNA is not done by direct aminoacylation of tRNAAsn but by specific tRNA-dependent transamidation of aspartyl-tRNAAsn. This transamidation pathway involves a nondiscriminating aspartyl-tRNA synthetase (AspRS) that charges both tRNAAsp and tRNAAsn with aspartic acid. Recently, it has been shown for the first time in an organism (Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1) that the transamidation pathway is the only route of synthesis of Asn-tRNAAsn but does not participate in Gln-tRNAGln formation. P. aeruginosa PAO1 has a nondiscriminating AspRS. We report here the identification of two residues in the anticodon recognition domain (H31 and G83) which are implicated in the recognition of tRNAAsn. Sequence comparisons of putative discriminating and nondiscriminating AspRSs (based on the presence or absence of the AdT operon and of AsnRS) revealed that bacterial nondiscriminating AspRSs possess a histidine at position 31 and usually a glycine at position 83, whereas discriminating AspRSs possess a leucine at position 31 and a residue other than a glycine at position 83. Mutagenesis of these residues of P. aeruginosa AspRS from histidine to leucine and from glycine to lysine increased the specificity of tRNAAsp charging over that of tRNAAsn by 3.5-fold and 4.2-fold, respectively. Thus, we show these residues to be determinants of the relaxed specificity of this nondiscriminating AspRS. Using available crystallographic data, we found that the H31 residue could interact with the central bases of the anticodons of the tRNAAsp and tRNAAsn. Therefore, these two determinants of specificity of P. aeruginosa AspRS could be important for all bacterial AspRSs.

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (aaRSs; E.C. 6.1.1.) are enzymes that catalyze the attachment of amino acids to their cognate tRNAs in a two-step reaction. They play a key role in the faithful expression of the genetic code by the specificity of the reaction they catalyze. It was once thought that all organisms possess one aaRS for each of the 20 unmodified amino acid species present in proteins. However, it has been shown that some organisms do not possess all 20 aaRSs (4; reviewed in references 14 and 15) and that some aaRSs have a relaxed specificity (27, 35). This is the case for nondiscriminating glutamyl-tRNA synthetases (ND-GluRSs), present in archaea and in most bacteria (reviewed in reference 28), and for nondiscriminating aspartyl-tRNA synthetases (ND-AspRSs), present in archaea (7) and some bacteria (24). In addition to their usual substrates, these enzymes charge tRNAGln and tRNAAsn with glutamate and aspartate, respectively. This relaxed specificity is complemented by the presence of a heterotrimeric tRNA-dependent amidotransferase (AdT). The amidotransferase corrects the misacylated tRNAs by adding the missing amide group to the amino acid on the mischarged tRNA. This indirect route is called the transamidation pathway (6). Gram-positive bacteria were the first organisms found to lack a gene coding for GlnRS (35). It is now known that they use the transamidation pathway for the synthesis of Gln-tRNAGln. Later it was demonstrated that the AdT from some organisms could transform Asp-tRNAAsn into Asn-tRNAAsn in vitro and in vivo (2, 8, 24, 25). Recent genomic studies revealed that some organisms do not possess an AsnRS but possess a GlnRS and an AdT. The first two examples of complete genome sequences with these characteristics were those of Neisseria meningitidis (23, 31) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (30). It is generally assumed that the absence of an AsnRS in an organism correlates with the presence of the AdT and of a nondiscriminating AspRS, the two ingredients needed for the formation of Asn-tRNA by the transamidation pathway. Therefore, it has been postulated that these organisms could use the transamidation pathway for the formation of Asn-tRNA. This has recently been demonstrated in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 (1). Since the discriminating bacterial AspRSs are very similar to the nondiscriminating ones, it is thought that only a few specific residues are responsible for the specificity of the enzyme. This is the case for archaeal AspRSs, as only two different amino acid changes were shown to be responsible for the recognition of tRNAAsn (10, 11). Until now, the specificity of a bacterial AspRS could not be determined from only its primary sequence. We report here the identification of two residues responsible for the recognition of tRNAAsn by the AspRS from P. aeruginosa, and possibly by all eubacterial nondiscriminating AspRSs. These findings could help our understanding of the evolution of bacterial species by making possible a better comprehension of the properties and evolution of the aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media.

Escherichia coli CS89 [F− thi-1 hisG4 Δ(gpt-proA)62 argE3 thr-1 leuB6 kdgK51 rfbD1 ara-14 lacY1 galK2 xyl-5 mtl-1 supE44 tsx-33 rpsL31 tls-1 Tetr] (22) was kindly provided by Gilbert Eriani. P. aeruginosa PAO1 and ADD1976 (miniD-180) were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C. For the growth of P. aeruginosa transformants, 500 μg/ml of carbenicillin was added. E. coli DH5α [F′ endA1 hsdR17 (rK− mK+) supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA (Nalr) relA1 Δ(lacIZYA-argF)U169 deoR (φ80dlacZΔ(lacZ)M15)] was also grown in LB medium at 37°C, with 100 μg/ml of ampicillin for the growth of transformants. E. coli CS89 was grown in low-salt LB medium (0.5 g NaCl/liter) at 30°C or 42°C. The selection of transformants was done with the addition of 100 μg/ml of ampicillin. The shuttle vectors pUCPSK and pUCPKS (33) were used for cloning aspS in E. coli and Pseudomonas and for the overexpression of the cloned gene with a coupled T7 RNA polymerase/T7 promoter (3).

Enzymes and chemicals.

Restriction enzymes, T4 DNA ligase, and alkaline phosphatase were all from New England Biolabs Inc. Ampicillin, tetracycline, and carbenicillin were purchased from Sigma Aldrich Inc. [14C]Asp was from Amersham Biosciences Inc. Pfx DNA polymerase was purchased from Gibco BRL.

Cloning of aspS and overproduction of AspRS.

The aspS gene from P. aeruginosa PAO1 was previously cloned in the shuttle vector pUCPKS and extended to provide a tag of six histidines added to the C-terminal end (1). The overproduction and purification of the tagged wild-type and mutated AspRSs were conducted as described previously (1).

Sequencing and sequence analysis.

The sequencing of the wild-type and mutated aspS was done by the method of Sanger et al. (26). Nucleotide sequence data and derived amino acid sequences were analyzed using the Genetics Computer Group software version 10.3 (Accelrys Inc., San Diego, Calif.), using the programs FASTA, TFASTA, and PILEUP.

Mutagenesis.

Site-specific mutagenesis of the wild-type aspS gene from P. aeruginosa was performed using two mutagenic complementary primers carrying mismatches with the template DNA (34). PCR was performed using Pfx DNA polymerase, in a reaction mixture in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. A first denaturation step was performed at 94°C for 4 min. Then, a 30-second step at 94°C was followed by an annealing step at 50°C for 45 seconds, followed by an elongation step at 68°C for 14 min, all three steps being repeated for 30 cycles. The PCR product was then digested with DpnI by adding 20 units of the enzyme to the reaction mixture and incubating at 37°C for 1 h. Ten microliters of the digested DNA was then used to transform P. aeruginosa by the method previously described (16).

Complementation assays.

E. coli CS89 was transformed (20) with different vectors expressing or not the different AspRSs (1), plated on low-salt LB medium, and incubated at 30°C. Complementation assays were done (22) by incubating positive clones at 30°C and 42°C.

Purification of E. coli tRNAAsn.

The E. coli genome contains a single species of tRNAAsn gene (http://lowelab.ucsc.edu/GtRNAdb/Esch_coli_K12/Esch_coli_K12-summary.html). This tRNA was purified from unfractionated E. coli tRNA as a hybrid with the 24-mer oligodeoxyribonucleotide probe 5′-TGACTGGACTCGAACCAGTGACAT-3′, complementary to its T arm, by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) under nondenaturing conditions (the detailed experimental procedure will be published elsewhere). After removing the probe by denaturing PAGE, the tRNAAsn was recovered by electroelution. It has an acceptor activity of 975 pmol aspartate/A260 unit with the heterologous P. aeruginosa AspRS.

Aminoacylation assays.

Aminoacylation assays were performed as previously described (1) using 67 nM of purified enzyme (wild-type or variant AspRS) and 6.7 μM of total P. aeruginosa tRNA or 2.3 μM of total E. coli tRNA in the reaction mixture.

Aspartylation of E. coli tRNA with E. coli AspRS.

The aspartylation of unfractionated tRNA from E. coli was done at 37°C in 100 mM Na-HEPES (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 30 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 2 mM ATP, and 40 μM of [14C]aspartate (205 mCi/mmol), using 179 nM of E. coli AspRS and 70 μM of unfractionated E. coli tRNA. After an incubation of 30 min, the reaction was stopped by the addition of sodium acetate (pH 5.5) to a final concentration of 0.1 M. The tRNA was then purified by phenol extraction and ethanol precipitated from the aqueous phase overnight at −20°C, and the pellet was washed twice with fresh 80% ethanol. After the second wash, the pellet was resuspended in an appropriate volume of diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated 10 mM MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) buffer, pH 6.5.

Molecular modeling.

Molecular modeling of the L30H variant of E. coli AspRS was done using the O software (17), using the function “Mutate_replace” to change the L30 to an H.

RESULTS

Correlation between the nature of two residues of AspRS and their tRNA specificities.

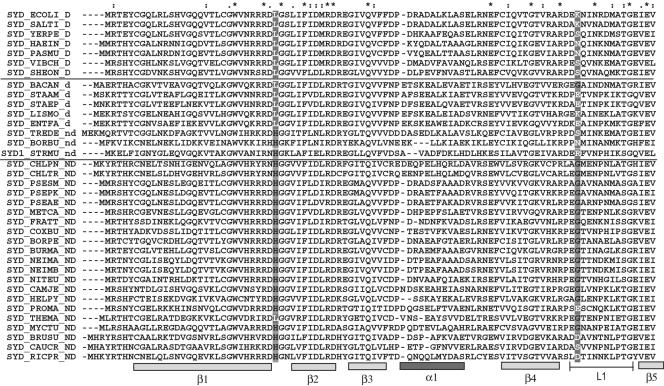

By examining the complete genomic sequence databases, we sorted prokaryotes into different groups, according to the presence or absence of AdT and AsnRS. We found that the β and lower γ proteobacteria lack an identifiable gene for AsnRS but have one for AdT, thus suggesting the presence of a nondiscriminating AspRS. We also found that the upper γ proteobacteria always have an AsnRS and no AdT, suggesting the presence of a discriminating AspRS. Peptide sequence alignment of discriminating and nondiscriminating prokaryotic AspRS was done for several organisms for which genomic sequences were available (Fig. 1). By sequence comparison, we found two residues, one being the last of a conserved motif (27R-R-R-D-H/L) in the first conserved β barrel of the enzyme and the other part of a loop (L1), whose identities correlate with the putative nondiscriminating or discriminating activities of AspRS. Figure 1 shows the peptide sequence alignment and the identities of residues 31 and 83 of each AspRS. When the genomic analysis suggests that AspRS is nondiscriminating (_ND in Fig. 1), a histidine is present at position 31 and a glycine is usually present at position 83; on the other hand, when the analysis suggests that it is discriminating (_D in Fig. 1), residue 31 is a leucine and residue 83 is any of several residues (lysine in E. coli). When both AsnRS and AdT are present, the AspRS could either be discriminating or nondiscriminating (_d or _nd in Fig. 1), as charging tRNAAsn with Asp would not result in toxicity for the cell.

FIG. 1.

Sequence alignment of the anticodon recognition domain from AspRSs of various organisms. The data are from complete genome databases. AspRSs are considered discriminating (_D) in the presence of an AsnRS and in the absence of an AdT in a given organism. AspRSs are usually considered as putatively discriminating (_d) but may also be putatively nondiscriminating (_nd) when in the presence of an AdT and an AsnRS. AspRSs from organisms lacking an AsnRS but having an AdT are considered nondiscriminating (_ND). Residues corresponding to histidine 31 and glycine 83 of P. aeruginosa AspRS are shaded. The names of the sequences are from the SwissProt database.

The toxicity of P. aeruginosa AspRS for E. coli is lost for the H31L, G83K, and H31L G83K mutants.

Plasmids containing wild-type P. aeruginosa AspRS and its variants were constructed and used to transform E. coli and P. aeruginosa. For the constructions with the insert in inverse orientation that contained but did not express the wild-type or the variant AspRS, transformants were found in both E. coli and P. aeruginosa. For the constructions that expressed the wild-type AspRS, surprisingly, we found transformants only in P. aeruginosa. Even in the absence of isopropyl-β-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) induction, transformants with the lac promoter upstream of the aspS structural genes were not observed in E. coli. This suggests that the AspRS of P. aeruginosa is toxic for E. coli, even at low intracellular concentration. This toxicity could be due to the depletion of free tRNAAsn by mischarging with Asp and thus could be suppressed by mutating a residue responsible for the recognition of tRNAAsn or important for the activity of the enzyme. For the constructions that expressed the variant AspRS, positive colonies were found for E. coli and P. aeruginosa, suggesting that these variants are no longer toxic for E. coli. Since the H31L variant complemented the aspS thermosensitive mutant CS89 of E. coli (results not shown), its lack of toxicity is not due to an inactivation of the AspRS but to the suppression or diminution of the recognition of E. coli tRNAAsn.

Specificity of wild-type P. aeruginosa AspRS and of its H31L, G83K, and H31L G83K variants for their homologous and heterologous tRNA substrates.

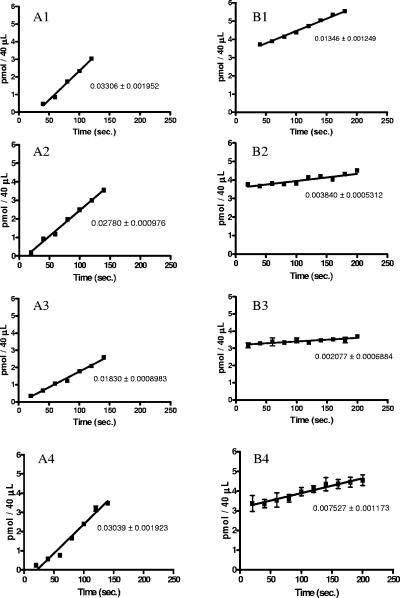

The results obtained for the aminoacylation of unfractionated P. aeruginosa tRNA with the different AspRSs did not show significant differences between the variants and the wild-type enzyme (results not shown; see Discussion). Figure 2 shows the aminoacylation activity of the wild-type and variant AspRSs on unfractionated E. coli tRNA. This deacylated tRNA either was used without previous treatment or was previously aspartylated using E. coli AspRS. In the preaspartylated tRNA sample, only tRNAAsp was aspartylated, as E. coli AspRS is discriminating. Thus, in the nonaspartylated tRNA preparation, P. aeruginosa AspRS could aminoacylate both tRNAAsp and tRNAAsn, but in the preaspartylated preparation, only tRNAAsn could be charged by P. aeruginosa AspRS, as all tRNAAsp was aspartylated. We see in Fig. 2 that the initial rate of the aspartylation reaction is slightly slower for the three variants versus the wild-type enzyme, for the tRNA sample that was not preaspartylated. The H31L, G83K, and H31L G83K variants are, respectively, about 84%, 55%, and 92% as fast as the wild-type AspRS. Figure 2 also shows that the initial rate of the aspartylation of unfractionated tRNA preaspartylated with E. coli AspRS is significantly slower for the three variants than for the wild-type enzyme. The H31L, G83K, and H31L G83K variants are, respectively, 28%, 15%, and 56% as fast as the wild-type enzyme, thus revealing that they are less efficient in the aspartylation of tRNAAsn. Under the conditions used, where ATP concentration is saturating, aspartate concentration is at the Km value (40 μM), tRNA concentration is lower than the Km (see below), and the initial rate of reaction is an indirect measure of the specificity constant kcat/Km (12); tRNAAsn concentration was 0.05 μM, about 5% the Km of P. aeruginosa AspRS for pure E. coli tRNAAsn (1.1 μM; results not shown). Therefore, we used the initial-velocity results presented in Fig. 2 to calculate the kcat/Km values of the four enzymes for E. coli tRNAAsp and tRNAAsn (Table 1). The relative specificities for tRNAAsp versus tRNAAsn of the H31L, G83K, and H31L G83K variants over the wild-type ND-AspRS are 3.5, 4.2, and 1.9, respectively. The validity of our conditions for these measurements of kcat/Km is confirmed by the fact that similar values (120,000 ± 10,000 M−1 s−1 versus 140,000 ± 20,000 M−1 s−1) were found from the independently determined kcat and Km values for the aspartylation of pure E. coli tRNAAsn with P. aeruginosa AspRS. Whether this increased specificity is due to an augmentation of the Km value of the variant enzymes for tRNAAsn or to a decreased kcat remains to be elucidated.

FIG. 2.

Aminoacylation of deacylated (A) and preaspartylated (B) unfractionated tRNA from E. coli by P. aeruginosa wild-type AspRS (1) and H31L (2), G83K (3), and H31L G83K (4) variants, all at 67 nM. Data shown represent the means of two or three independent experiments, with standard errors indicated. Reactions were made under conditions permitting extrapolation of kcat/Km from the initial rate of the reaction, that is, when ATP concentration is saturating, Asp concentration is around Km (40 μM), and aspartylable E. coli tRNA concentration (tRNAAsp plus tRNAAsn) is 0.15 μM, about 5% of Km.

TABLE 1.

Specificity of wild-type P. aeruginosa AspRS and of its H31L, G83K, and H31L G83K variants for the aspartylation of E. coli tRNAAsp and tRNAAsn in unfractionated tRNA

| Enzyme |

kcat/Km (s−1 M−1) for formation of:

|

Relative specificitya | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asp-tRNAAsp | Asp-tRNAAsn | ||

| WTb | 180,000 ± 10,000 | 120,000 ± 10,000 | 1.5 |

| H31L | 170,000 ± 5,000 | 33,000 ± 5,000 | 5.2 |

| G83K | 113,000 ± 4,000 | 18,000 ± 6,000 | 6.3 |

| H31L G83K | 139,000 ± 8,000 | 50,000 ± 8,000 | 2.8 |

Ratio of specificity constant (kcat/Km) values for tRNAAsp aspartylation over those for tRNAAsn.

WT, wild type.

DISCUSSION

The first hint that the AspRS of P. aeruginosa is nondiscriminating is the apparent toxicity for E. coli cells, even without AspRS overproduction. The toxicity of a nondiscriminating AspRS could be due, in theory, to two different fates of Asp-tRNAAsn: the misincorporation of Asp in proteins in response to Asn codons, which would lead to inactive proteins, or the depletion of the free tRNAAsn normally aminoacylated by the AsnRS of E. coli. This first fate is unlikely to occur, since EF-Tu from chloroplasts cannot bind Glu-tRNAGln (29) and since EF-Tu can differentiate between correctly acylated and misacylated tRNAs by a dynamic compensation mechanism (19). The second possible fate is more plausible; since no protein in E. coli can recognize Asp-tRNAAsn, this product would remain unmodified in the cell, leading to a depletion of free tRNAAsn.

Because of their primary and quaternary structures, AspRSs are class IIb aaRSs, together with LysRS and AsnRS (9). These three aaRSs are characterized by a C-terminal catalytic domain separated by a small “hinge” region from the N-terminal anticodon-binding domain. The N-terminal domain, where the two above-mentioned substitutions are located, should be responsible for the specificity of tRNA recognition, since it binds the tRNA anticodon. Since the H31L variant is no longer toxic for E. coli, there may be either an inactivation of the enzyme (suppression of recognition of tRNAAsp and tRNAAsn) or the suppression of the recognition of tRNAAsn alone. The complementation of the E. coli CS89 thermosensitive aspS mutant by the H31L AspRS showed that the second possibility was valid, that is, that the replacement of histidine 31 by leucine suppressed the recognition of tRNAAsn, thus converting the nondiscriminating AspRS to an active, discriminating one. Consequently, the H31L AspRS no longer recognizes E. coli tRNAAsn but still recognizes tRNAAsp. Interestingly, the presence of an L residue at the corresponding position in E. coli wild-type discriminating AspRS (D-AspRS) does not allow it to aspartylate the suppressor tRNAAsp (CUA) efficiently enough to suppress a lacZ-amber gene, whereas its L30F variant, which has a fivefold specificity increase for this suppressor tRNAAsp, does suppress it (21). Therefore, for both P. aeruginosa ND-AspRS and E. coli D-AspRS, the presence of an L residue at this position restricts tRNA recognition.

Aminoacylation assays were done on both E. coli and P. aeruginosa total tRNA preparations to see whether there was a difference between the activities of the enzymes with the homologous and the heterologous tRNAs. With regard to the aminoacylation of the unfractionated tRNA from E. coli, we observed that the three variants are less efficient than the wild type in the aspartylation of deacylated tRNA (Fig. 2, panels A1 to A4). However, the effects of the mutations are much larger when we compare the aspartylation of tRNAAsn by the variants to that of the wild-type enzyme (Fig. 2, panels B1 to B4). This shows that a single amino acid change can alter the specificity of an AspRS for its tRNAs, making it more discriminating. It is thought that the ancient pathway for the synthesis of Asn-tRNAAsn is the transamidation pathway, involving an ND-AspRS and AdT (14). After a duplication of the gene coding for the ND-AspRS and its evolution towards an AsnRS, it is thought that the ND-AspRS became discriminating, as it was no longer needed to be nondiscriminating. Then, the genes coding for the three subunits of the AdT could simply be removed from the chromosome, if not needed, provided that the pathway of synthesis of Gln-tRNAGln is also a direct one, involving a GlnRS. As reported before, a small decrease (11, 18) or increase (21) in the efficiency of an aaRS can lead to a detectable phenotype. In the case of H31L and G83K variants, 3.5-fold and 4.2-fold increases in the specificity of the enzyme, respectively, were enough to abolish the toxicity of the enzymes in vivo. This was also the case for the H31L G83K variant, as the specificity for tRNAAsp aspartylation was increased by 1.9-fold. However, our results suggest that there is a negative interaction between these positions, as the double mutant did not gain specificity compared to the single mutants tested. The molecular basis of this interaction is still to be determined. Our results are in accordance with those reported on the mutation of residues 28 and 77 of archaeal ND-AspRS (11). Even though archaeal and bacterial AspRSs are evolutionarily distant (36), mutation of H28 and P77 of the archaeal AspRS of Deinococcus radiodurans (AspRS2) to a glutamine and a lysine, respectively, increased by around threefold the specificity for tRNAAsp aspartylation over that of tRNAAsn. Moreover, a similar negative interaction between the two mutated residues was observed, as the double mutant showed less specificity for tRNAAsp than the single mutants tested (11).

The exact mechanism by which histidine 31 confers a relaxed specificity upon the AspRS remains to be understood. Molecular modeling suggests that this could be the result of a more stable interaction between the enzyme and the anticodon of tRNAAsn. As Fig. 3 shows, a hydrogen bond is possible between this histidine and the central nucleoside of the anticodon of tRNAAsp. This base is a uracil, as in tRNAAsn. The anticodons of tRNAAsp and tRNAAsn are 34Q-U-C and 34Q-U-U, respectively. Histidine 31, by stabilizing the interaction with the central nucleoside, could permit a suboptimal interaction with other bases of the anticodon. Hence, the enzyme would accommodate a cytosine or a uracil as the third base of the anticodon. When a leucine is present at position 31, no hydrogen bond is possible and the interactions between the tRNA and the AspRS must be optimal for the aminoacylation to occur. These optimal interactions are made only with cytosine at the third position of the anticodon. Thus, only tRNAAsp would be recognized by the wild-type AspRS.

FIG. 3.

Molecular modeling around residue 30 of the E. coli AspRS. The bases and residues are numbered from Protein Data Bank file 1C0A. Hydrogen bonds are indicated by dashed lines, with the distance of the bond in angstroms.

For residue G83 in P. aeruginosa AspRS, we can only speculate about its function in the recognition of tRNAAsn. This residue is part of a conserved L1 loop in all class IIb aaRSs, which is known to interact with base 36 of the anticodon (5, 10, 32). The glycine at this position in most nondiscriminating AspRSs could enhance the mobility of this loop, permitting the recognition of a uracil or a cytosine at position 36 of the tRNA. Therefore, this mobility could improve the recognition of tRNAAsn (GUU) and thus make the AspRS nondiscriminating.

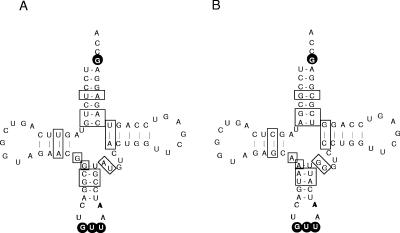

For the aminoacylation of tRNAs from P. aeruginosa, we did not observe a significant difference in the initial rates of reaction, suggesting that the mutations did not affect the recognition of tRNAAsp or tRNAAsn. The reason why the variants still recognize tRNAAsn from P. aeruginosa remains mysterious. However, it is reasonable to think that the differences in the tRNAAsn from E. coli and P. aeruginosa shown in Fig. 4 are responsible for this behavior. There are 18 differences out of 76 bases in the two tRNAs, mainly located in the acceptor and anticodon arms. Even if those differences do not affect the identity elements of tRNAAsn (13), they could be important for optimal interactions with the enzymes of the two organisms. In particular, tRNAAsn from both organisms coevolved by interacting with their respective aaRSs. Thus, the behavior of the H31L and G83K variants with P. aeruginosa tRNAAsn could be explained by the fact that other interactions take place between residues of the ND-AspRS and nucleotides of tRNAAsn. The single change of histidine 31 to a leucine or of glycine 83 to a lysine could decrease the recognition of P. aeruginosa tRNAAsn, but not significantly. With E. coli tRNAAsn, this change would be more dramatic, since the latter did not coevolve with an ND-AspRS.

FIG. 4.

Sequence comparison of tRNAAsn from (A) E. coli and (B) P. aeruginosa. The sequences are derived from the genes found at the genomic tRNA database (http://lowelab.ucsc.edu/GtRNAdb/) and thus do not show modified nucleotides. Differences between the two tRNAs are boxed. White letters on black circles represent the identity elements of E. coli tRNAAsn, according to reference 13.

This work presents evidence that discriminating and nondiscriminating bacterial AspRSs are closely related. It shows that only one or two amino acid changes in a bacterial ND-AspRS could have been responsible for the appearance of a discriminating character during evolution. Structural studies of these three variants, especially H31L, are needed to confirm our model.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Gilbert Eriani for the E. coli CS89 strain and to Peter Rehse for helping with the molecular modeling.

This work was supported by grant MT13564 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) to P.H.R., grant OGP0009597 from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) to J.L., and grant 2003-ER-2481 from the “Fonds pour la Formation de Chercheurs et l'Aide à la Recherche du Québec” to P.H.R. and J.L. D. Bernard was a CIHR Strategic Training Program in Antibiotic Resistance doctoral fellow, P.M.A. was a doctoral fellow from the “Ministère de l'Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche Scientifique de Côte d'Ivoire,” and D. Beaulieu was an undergraduate fellow of CREFSIP.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akochy, P. M., D. Bernard, P. H. Roy, and J. Lapointe. 2004. Direct glutaminyl-tRNA biosynthesis and indirect asparaginyl-tRNA biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J. Bacteriol. 186:767-776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker, H. D., B. Min, C. Jacobi, G. Raczniak, J. Pelaschier, H. Roy, S. Klein, D. Kern, and D. Soll. 2000. The heterotrimeric Thermus thermophilus Asp-tRNAAsn amidotransferase can also generate Gln-tRNAGln. FEBS Lett. 476:140-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunschwig, E., and A. Darzins. 1992. A two-component T7 system for the overexpression of genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene 111:35-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bult, C. J., O. White, G. J. Olsen, L. Zhou, R. D. Fleischmann, G. G. Sutton, J. A. Blake, L. M. FitzGerald, R. A. Clayton, J. D. Gocayne, A. R. Kerlavage, B. A. Dougherty, J. F. Tomb, M. D. Adams, C. I. Reich, R. Overbeek, E. F. Kirkness, K. G. Weinstock, J. M. Merrick, A. Glodek, J. L. Scott, N. S. Geoghagen, and J. C. Venter. 1996. Complete genome sequence of the methanogenic archaeon, Methanococcus jannaschii. Science 273:1058-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charron, C., H. Roy, M. Blaise, R. Giege, and D. Kern. 2003. Non-discriminating and discriminating aspartyl-tRNA synthetases differ in the anticodon-binding domain. EMBO J. 22:1632-1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curnow, A. W., K. Hong, R. Yuan, S. Kim, O. Martins, W. Winkler, T. M. Henkin, and D. Soll. 1997. Glu-tRNAGln amidotransferase: a novel heterotrimeric enzyme required for correct decoding of glutamine codons during translation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:11819-11826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curnow, A. W., M. Ibba, and D. Soll. 1996. tRNA-dependent asparagine formation. Nature 382:589-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curnow, A. W., D. L. Tumbula, J. T. Pelaschier, B. Min, and D. Soll. 1998. Glutamyl-tRNAGln amidotransferase in Deinococcus radiodurans may be confined to asparagine biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:12838-12843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eriani, G., M. Delarue, O. Poch, J. Gangloff, and D. Moras. 1990. Partition of tRNA synthetases into two classes based on mutually exclusive sets of sequence motifs. Nature 347:203-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feng, L., D. Tumbula-Hansen, H. Toogood, and D. Soll. 2003. Expanding tRNA recognition of a tRNA synthetase by a single amino acid change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:5676-5681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng, L., J. Yuan, H. Toogood, D. Tumbula-Hansen, and D. Soll. 2005. Aspartyl-tRNA synthetase requires a conserved proline in the anticodon-binding loop for tRNAAsn recognition in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 280:20638-20641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fersht, A. 1985. Enzyme structure and mechanism, 2nd ed. W. H. Freeman and Company, New York, N.Y.

- 13.Giege, R., and M. Frugier. 2003. Transfer RNA structure and identity, p. 1-24. In J. Lapointe and L. Brakier-Gingras (ed.), Translation mechanisms. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York, N.Y.

- 14.Ibba, M., and D. Soll. 2000. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:617-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ibba, M., and D. Soll. 2001. The renaissance of aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis. EMBO Rep. 2:382-387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Irani, V. R., and J. J. Rowe. 1997. Enhancement of transformation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 by Mg2+ and heat. BioTechniques 22:54-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones, T. A., J. Y. Zou, S. W. Cowan, and Kjeldgaard. 1991. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 47(Pt. 2):110-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kowal, A. K., C. Kohrer, and U. L. RajBhandary. 2001. Twenty-first aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase-suppressor tRNA pairs for possible use in site-specific incorporation of amino acid analogues into proteins in eukaryotes and in eubacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:2268-2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LaRiviere, F. J., A. D. Wolfson, and O. C. Uhlenbeck. 2001. Uniform binding of aminoacyl-tRNAs to elongation factor Tu by thermodynamic compensation. Science 294:165-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maniatis, T., E. F. Fritsch, and J. Sambrook. 1982. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 21.Martin, F., S. Barends, and G. Eriani. 2004. Single amino acid changes in AspRS reveal alternative routes for expanding its tRNA repertoire in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:4081-4089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin, F., G. J. Sharples, R. G. Lloyd, S. Eiler, D. Moras, J. Gangloff, and G. Eriani. 1997. Characterization of a thermosensitive Escherichia coli aspartyl-tRNA synthetase mutant. J. Bacteriol. 179:3691-3696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parkhill, J., M. Achtman, K. D. James, S. D. Bentley, C. Churcher, S. R. Klee, G. Morelli, D. Basham, D. Brown, T. Chillingworth, R. M. Davies, P. Davis, K. Devlin, T. Feltwell, N. Hamlin, S. Holroyd, K. Jagels, S. Leather, S. Moule, K. Mungall, M. A. Quail, M. A. Rajandream, K. M. Rutherford, M. Simmonds, J. Skelton, S. Whitehead, B. G. Spratt, and B. G. Barrell. 2000. Complete DNA sequence of a serogroup A strain of Neisseria meningitidis Z2491. Nature 404:502-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raczniak, G., H. D. Becker, B. Min, and D. Soll. 2001. A single amidotransferase forms asparaginyl-tRNA and glutaminyl-tRNA in Chlamydia trachomatis. J. Biol. Chem. 276:45862-45867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salazar, J. C., R. Zuniga, G. Raczniak, H. Becker, D. Soll, and O. Orellana. 2001. A dual-specific Glu-tRNA(Gln) and Asp-tRNA(Asn) amidotransferase is involved in decoding glutamine and asparagine codons in Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. FEBS Lett. 500:129-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanger, F., S. Nicklen, and A. R. Coulson. 1977. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:5463-5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schon, A., C. G. Kannangara, S. Gough, and D. Soll. 1988. Protein biosynthesis in organelles requires misaminoacylation of tRNA. Nature 331:187-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soll, D., and M. Ibba. 2003. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase structure and evolution. p. 25-33. In J. Lapointe and L. Brakier-Gingras (ed.), Translation mechanisms. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York, N.Y.

- 29.Stanzel, M., A. Schon, and M. Sprinzl. 1994. Discrimination against misacylated tRNA by chloroplast elongation factor Tu. Eur. J. Biochem. 219:435-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stover, C. K., X. Q. Pham, A. L. Erwin, S. D. Mizoguchi, P. Warrener, M. J. Hickey, F. S. Brinkman, W. O. Hufnagle, D. J. Kowalik, M. Lagrou, R. L. Garber, L. Goltry, E. Tolentino, S. Westbrock-Wadman, Y. Yuan, L. L. Brody, S. N. Coulter, K. R. Folger, A. Kas, K. Larbig, R. Lim, K. Smith, D. Spencer, G. K. Wong, Z. Wu, and I. T. Paulsen. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406:959-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tettelin, H., N. J. Saunders, J. Heidelberg, A. C. Jeffries, K. E. Nelson, J. A. Eisen, K. A. Ketchum, D. W. Hood, J. F. Peden, R. J. Dodson, W. C. Nelson, M. L. Gwinn, R. DeBoy, J. D. Peterson, E. K. Hickey, D. H. Haft, S. L. Salzberg, O. White, R. D. Fleischmann, B. A. Dougherty, T. Mason, A. Ciecko, D. S. Parksey, E. Blair, H. Cittone, E. B. Clark, M. D. Cotton, T. R. Utterback, H. Khouri, H. Qin, J. Vamathevan, J. Gill, V. Scarlato, V. Masignani, M. Pizza, G. Grandi, L. Sun, H. O. Smith, C. M. Fraser, E. R. Moxon, R. Rappuoli, and J. C. Venter. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B strain MC58. Science 287:1809-1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tumbula-Hansen, D., L. Feng, H. Toogood, K. O. Stetter, and D. Soll. 2002. Evolutionary divergence of the archaeal aspartyl-tRNA synthetases into discriminating and nondiscriminating forms. J. Biol. Chem. 277:37184-37190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watson, A. A., R. A. Alm, and J. S. Mattick. 1996. Construction of improved vectors for protein production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene 172:163-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiner, M. P., G. L. Costa, W. Schoettlin, J. Cline, E. Mathur, and J. C. Bauer. 1994. Site-directed mutagenesis of double-stranded DNA by the polymerase chain reaction. Gene 151:119-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilcox, M., and M. Nirenberg. 1968. Transfer RNA as a cofactor coupling amino acid synthesis with that of protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 61:229-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woese, C. R., G. J. Olsen, M. Ibba, and D. Soll. 2000. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, the genetic code, and the evolutionary process. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:202-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]