Abstract

The transcription factor MafA/RIPE3b1 is an important regulator of insulin gene expression. MafA binds to the insulin enhancer element RIPE3b (C1-A2), now designated as insulin MARE (Maf response element). The insulin MARE element shares an overlapping DNA-binding region with another insulin enhancer element A2. A2.2, a β-cell-specific activator, like the MARE-binding factor MafA, binds to the overlapping A2 element. Our previous results demonstrated that two nucleotides in the overlapping region are required for the binding of both factors. Surprisingly, instead of interfering with each other's binding activity, the MafA and the A2-binding factors co-operatively activated insulin gene expression. To understand the molecular mechanisms responsible for this functional co-operation, we have determined the nucleotides essential for the binding of the A2.2 factor. Using this information, we have constructed non-overlapping DNA-binding elements and their derivatives, and subsequently analysed the effect of these modifications on insulin gene expression. Our results demonstrate that the overlapping binding site is essential for maximal insulin gene expression. Furthermore, the overlapping organization is critical for MafA-mediated transcriptional activation, but has a minor effect on the activity of A2-binding factors. Interestingly, the binding affinities of both MafA and A2.2 to the overlapping or non-overlapping binding sites were not significantly different, implying that the overlapping binding organization may increase the activation potential of MafA by physical/functional interactions with A2-binding factors. Thus our results demonstrate a novel mechanism for the regulation of MafA activity, and in turn β-cell function, by altering expression and/or binding of the A2.2 factor. Our results further suggest that the major downstream targets of MafA will in addition to the MARE element have a binding site for the A2.2 factor.

Keywords: insulin gene transcription, MafA, Maf-response element, overlapping element, RIPE3b, transcription factors

Abbreviations: EMSA, electrophoretic mobility-shift assay; MARE, Maf response element; PDX-1, pancreatic duodenal homeobox-1

INTRODUCTION

For the past 20 years, efforts have been made to decipher the molecular mechanisms regulating β-cell-specific expression of the insulin gene. These efforts have resulted in the identification of several critical enhancer elements as regulators of insulin gene expression. Of these elements, three conserved insulin enhancer elements, A3 (−201 to −196 bp) [1–4], RIPE3b/C1-A2 (−126 to −101 bp) [5] and E1 (−100 to −91 bp) [6,7], play important roles in regulating β-cell-specific expression of the insulin gene. A member of the homeodomain family of transcription factors, PDX-1 (pancreatic duodenal homeobox-1), binds the A3 element [8–10]. Heterodimers of ubiquitous E2A, HEB [11] and the cell-type-enriched bHLH (basic helix–loop–helix) family member, BETA2 [12], bind the E1 element. Recently, the β-cell-specific RIPE3b-binding factor (RIPE3b1) was identified and cloned as the mammalian homologue of avian MafA [13–15]. Limited, but not identical, cellular distribution of transcription factors PDX-1, BETA2 and MafA suggests that cell-specific insulin gene expression results from a unique combination of transcription factors in pancreatic β-cells.

In addition to cell-type-specific expression, factors binding to the enhancer elements A3, E1 and RIPE3b regulate insulin gene expression in response to an acute increase in glucose concentration [16–20]. Interestingly, in cell-culture models of glucotoxicity, both RIPE3b1/MafA and PDX-1 binding activities, and insulin gene expression were inhibited by chronic hyperglycaemia [21]. Similarly, in an in vivo model of glucotoxicity (90% partial pancreatectomy), PDX-1, BETA2 and MafA levels were also inhibited in rat islets isolated after the development of diabetes [22,23] (T. Kondo, T. Salameh, W. Nishimura and A. Sharma, unpublished work). Studies of mice carrying homozygous null mutations in the pdx-1 [24–26] and beta2 [27] genes revealed another important function of these factors in regulating pancreatic development and differentiation of β-cells. Mice that are heterozygous for pdx-1 have impaired glucose tolerance [28], suggesting that loss of a single copy of this gene may predispose individuals to develop diabetes. Consistent with this observation, humans with a mutation in a single allele of either pdx-1/ipf1 or beta2/neuroD1 [29,30] have defective insulin secretion and develop MODY (maturity onset diabetes of the young). Like PDX-1 and BETA2, the Maf family of transcription factors plays an important role in cell determination and control of cellular differentiation. For instance, the avian homologue of MafA is an important regulator of lens development [31–33]. We suggest that the newly identified mammalian MafA (RIPE3b1) will also have an important role in pancreatic development. Furthermore, like PDX-1 and BETA2, a moderate alteration in the expression/function of MafA may result in the development of diabetes. Thus the study of insulin enhancer elements and transcription factors will have a major impact on our ability to control: (i) metabolic and cell-specific regulation of insulin gene expression, (ii) pancreatic development and differentiation of β-cells, and (iii) development and progression of diabetes.

Insulin enhancer element RIPE3b (−126 to −101 bp) [5] was initially suggested to contain C1 (−116 to −107 bp), the binding site for the RIPE3b1 activator [5,34], and A2 (−126 to −113 bp) [35–37] elements. However, we demonstrated that both C1 and A2 elements together constitute a large binding site (from −124 to −107 bp) for the RIPE3b1 factor [38]. Since the RIPE3b1 transcription factor was identified as MafA [13], we now refer to the binding site −124 to −107 bp as MARE (Maf response element). The Maf family of transcription factors recognizes the extended DNA element, TGC(N)6–7GCA, but shows a significant variation in the DNA-binding specificity for individual family members [39–41]. The RIPE3b element shows moderate homology with the MAF consensus sequence (TGCN7GC, underlined residues represent conserved nucleotides). Conserved GC nucleotides between the Maf consensus sequence and RIPE3b element (−118, −117 bp and −109, −108 bp in rat insulin II gene) were important for the binding of RIPE3b1 factor [38]. Interestingly, nucleotides upstream of the conserved region (−122 and −121 bp) were also critical for binding of this factor [38]. While determining nucleotides essential for the binding of the RIPE3b1 factor to the C1 and A2 elements, we identified three DNA-binding complexes that would specifically bind to an extended A2 element (−139 to −113 bp). Two of these complexes were formed with nuclear extracts from non-insulin-producing cell lines, whereas nuclear extracts from insulin-producing cell lines were required for the formation of the A2.2 complex. We demonstrated that the A2-binding factors were distinct from the transcription factors PDX-1 and Nkx2.2 [38]. In the insulin enhancer region, MARE and the A2 elements share overlapping nucleotides (−124 to −113 bp), of which at least two base-pairs, −122 and −121, were required for the binding of both A2.2 and MafA factors. Furthermore, results of transient transfection studies demonstrated that both RIPE3b1 and A2.2 factors co-operatively activate insulin gene expression instead of interfering with each other's activity [38]. To our knowledge, this is the only example of two β-cell-specific factors binding to overlapping elements and regulating insulin gene expression. These results suggest that A2.2 factor either directly and/or indirectly controls the insulin gene expression by regulating MafA activity.

To understand the role of the overlapping binding region in regulating insulin gene expression, we constructed and analysed insulin reporter constructs with overlapping and non-overlapping enhancer elements. We also determined the nucleotides essential for the binding of the A2.2 factor, and confirmed that the binding site for this factor is distinct from the PDX-1 and Nkx 2.2 factors. We found that the overlapping enhancer element organization was not essential for the binding of either the A2.2 or MafA factor. Furthermore, the overlapping organization was not essential for the A2.2 factor-mediated transcriptional activation; however, it was critical for transcriptional activation mediated by MafA. Our results suggest that the functional/physical interaction between A2.2 and MafA due to the overlapping element organization was critical for enhancing the activation potential of MafA. Since moderate inhibition in the levels of insulin gene transcription factors contributes to the development of β-cell dysfunction, we suggest that interfering with the functional/physical interactions between A2.2 and MafA may result in a similar outcome.

EXPERIMENTAL

Tissue culture

The HIT T-15 cell line was obtained from A.T.C.C. (Rockville, MD, U.S.A.), and all experiments were conducted with cells between passage numbers 68 and 80. Dr J.-I. Miyazaki (Osaka University Medical School, Japan) kindly provided the MIN-6 cell line. HIT T-15 and MIN-6 cells were cultured in the Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with either 10 or 20% (w/v) fetal bovine serum respectively, 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37 °C under 5% CO2.

EMSAs (electrophoretic mobility-shift assays)

Oligonucleotides used as probes and competitors (Table 1) were synthesized by Sigma-Genosys (The Woodlands, TX, U.S.A.). Double-stranded oligonucleotide probes were radiolabelled with [α-32P]dCTP using the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I. Competition experiments were performed by simultaneous addition of radiolabelled probe and up to a 50-fold excess of unlabelled competitors to the binding reaction. Details of nuclear extract preparations, binding reactions, electrophoresis and analyses of gels have been described previously [38].

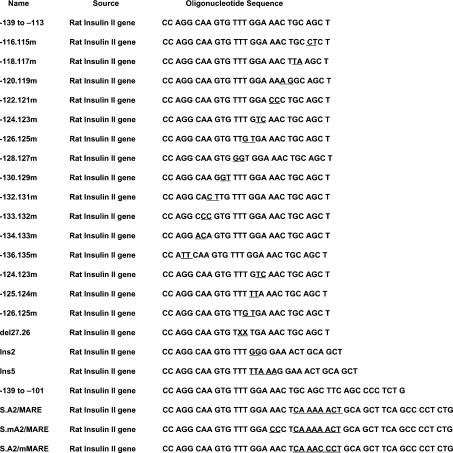

Table 1. Sequences of the oligonucleotides used as probes and competitors.

DNA constructs

The insulin reporter construct, −238 WT LUC (where WT stands for wild-type and LUC for luciferase) [17], and its derivatives with mutations at different base-pairs 125-124m LUC, 122-121m LUC and 110-09m LUC were described previously [38]. The QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, U.S.A.) was used to construct additional plasmids with specific mutations in the insulin enhancer. Double-stranded oligonucleotides containing separated wild-type A2 and MARE elements (nucleotides inserted are underlined), as well as desired mutations in these elements (boldface), were synthesized to construct S. A2/MARE LUC (−135 GCAAGTGTTTGGAAACTCAAAAACTGCAGCTTCAGCCCC −105 bp), S. mA2/MARE LUC (−139 CCAGGCAAGTGTTTGGACCCTCAAAA-ACTGCAGCTTCAGCCCC −105 bp) and S. A2/mMARE LUC (−135 GCAAGTGTTTGGAAACTCAAACCCTGCAGCTTCAGCCCCTCTG −101 bp). The −238 WT LUC plasmid was used as a template with these oligonucleotides to construct reporter plasmids with mutations at the desired positions in the insulin enhancer. Plasmids were sequenced to confirm the construction of each mutant plasmid. To avoid the effect of non-specific mutations outside the insulin enhancer region on the reporter gene expression, the plasmids were digested with restriction enzymes to release the inserts containing mutations in the insulin enhancer. These fragments were then used to replace the wild-type insulin enhancer from the −238 WT LUC construct, resulting in the generation of reporter plasmids that differed only at the specified mutation site in the insulin enhancer.

Luciferase assays

MIN-6 and HIT T-15 cells were transfected with the indicated amount of various reporter constructs and with 1 μg of pSVβ-gal plasmid (Promega, Madison, WI, U.S.A.), using Lipofectamine™ (Invitrogen, CA, U.S.A.). Whole cell extracts were prepared and luciferase activity was measured as described previously [38]. To determine β-galactosidase activity, 50 μl of cell lysate was incubated with 100 μl of 4 mg/ml ONPG (o-nitrophenyl β-D-galactopyranoside) and 400 μl of 60 mM Na2HPO4, 40 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM KCl and 1 mM MgSO4 (pH 7) in the presence of 0.5 μl of 2-mercaptoethanol at 37 °C until yellowish coloration developed (typically 2–4 h). The reaction was stopped by the addition of 500 μl of 1 M Na2CO3. β-Galactosidase activity was determined at absorbance A420. The luciferase activities were normalized to the internal control β-galactosidase activity. Transfection experiments were repeated several times, with at least two or three different plasmid preparations.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification of nucleotides essential for the binding of A2.2 factor

We previously reported that DNA-binding factors in the HIT T-15 nuclear extract can selectively bind the insulin enhancer region from −139 to −101 bp to form five specific DNA-binding complexes [38]. Only the RIPE3b1 (MafA) and RIPE3b2 complexes were formed with the −126 to −101 bp (RIPE3b/MARE) insulin enhancer probe. Formation of the remaining three complexes required the −139 to −113 bp A2 element probe. Interestingly, two base-pairs at the positions −122 and −121 were essential for the binding of both MafA and A2.2 activators. Yet, instead of interfering with each other's activity, these factors co-operatively activated insulin gene expression. As we have already determined the nucleotides essential for the binding of MafA and RIPE3b2 [38], in the present study we aimed at identifying the nucleotides required for the binding of A2-specific factors. To this end, we synthesized a series of oligonucleotides (−139 to −113 bp) corresponding to the A2 element with two base-pair substitution mutations.

EMSAs were performed, in the presence or absence of a 50-fold excess of unlabelled competitor, using a radiolabelled −139 to −113 bp rat insulin II enhancer element probe and HIT T-15 nuclear extracts (Figure 1A). The nucleotide sequence of the rat insulin II A2 element is fairly well conserved compared with the corresponding sequences from rat insulin I and human insulin genes. The sequences corresponding to the rat insulin II −129 to −113 bp are either identical or have conservative substitutions (A↔G or C↔T), but the sequence corresponding to −139 to −130 bp has five non-conservative substitutions. Consistent with this observation, competitors with mutations in the −136 to −131 bp region competed effectively with the binding of A2.2 activator to the −139 to −113 bp probe, while competitors with mutations between the positions −130 to −127 and −122 to −119 did not compete effectively. These results demonstrate that the nucleotides TGTT (−130 to −127 bp) and AACT (−122 to −119) are essential for the binding of the A2.2 factor. Furthermore, as shown earlier [38], a competitor oligonucleotide with mutations in the conserved Nkx2.2-binding site (positions −133 and −132) competed effectively (Figure 1A, lane 3). Also, as shown previously [38], mutating two guanines at −125 and −124 prevented both binding and transcriptional activation mediated by the A2.2 factor. Thus we were surprised to see effective competition by oligonucleotides with individual mutations at −125 and −124 bp [−126.125 and −124.123 bp (lanes 7 and 8)] for the binding of the A2.2 factor. To resolve this issue, competition analysis for the binding of A2.2 was performed using −139 to −113 bp probe and oligonucleotides with mutations at positions −126.125, −125.124 and −124.123 bp. As shown in Figure 1(B), oligonucleotides with a mutation in a single guanine nucleotide successfully competed for the ability of A2.2 to bind to the probe. However, mutating both guanine nucleotides (−125.124m) abolished the ability of this oligonucleotide to bind to the A2.2 factor. Our results demonstrate that at least one guanine nucleotide is required for the binding of the A2.2 factor.

Figure 1. Identification of nucleotide sequence critical for the DNA binding of A2.2 factor.

(A) HIT T-15 nuclear extracts were incubated with radiolabelled −139 to −113 bp rat insulin II enhancer element probe in the absence (−) or presence of 50-fold excess of indicated mutant oligonucleotides as unlabelled competitors. Binding reactions were analysed by EMSA, and specific DNA-binding complexes are indicated. The nucleotides critical for the formation of A2.2-binding complexes are underlined. The mutant competitors from 136.135m to 116.115m represents the −139 to −113 bp oligonucleotides with mutations in specified consecutive two nucleotides. (B) HIT T-15 nuclear extracts were incubated with radiolabelled −139 to −113 bp probe in the presence of 50-fold excess of oligonucleotides with mutations at positions −126.125, −125.124 or −124.123 bp as unlabelled competitors. Binding reactions were analysed by EMSA. The nucleotides critical for the formation of A2.2-binding complexes are underlined.

Effect of altering DNA-binding site on the A2.2-binding activity

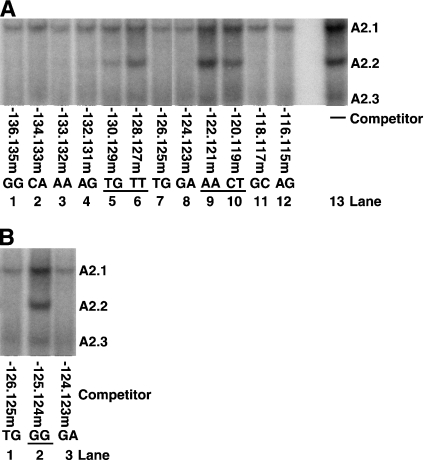

The results presented in Figure 1 demonstrate that the distance of a critical guanine from the TGTT and AACT half-sites can vary by one base-pair without a significant effect on the binding of the A2.2 factor. To test further the effect of exact spacing between the two half-sites on the binding of A2.2, oligonucleotides were synthesized with either a deletion of two or an insertion of two or five nucleotides; these were used as competitors in EMSA (Figure 2). The schematic in Figure 2(A) shows the sequence and positions of deleted and inserted nucleotides in the −139 to −113 bp oligonucleotide. HIT T-15 nuclear extract was incubated with labelled −139 to −113 bp probe in the absence or presence of increasing amounts (5–50-fold) of the indicated unlabelled competitor. As can be seen in Figure 2(B), unlabelled wild-type −139 to −113 bp oligonucleotide effectively competes for the binding of the A2.2 factor, while the oligonucleotides −128.127m and −130.129m, with mutations that are critical for binding, were ineffective competitors. We observed that the deletion or insertion of two base-pairs (del27.26 and Ins2) resulted in a reduction, but not complete loss, in the ability of these oligonucleotides to compete for the binding of the A2.2 factor [compare lanes 12 and 15 with wild-type (lane 3), or mutant competitors (lanes 6 and 9)]. However, the oligonucleotide with the insertion of five base-pairs was as ineffective of a competitor as the −128.127m and −130.129m oligonucleotides (compare lane 18 with lanes 6 and 9).

Figure 2. Effect of altering distance between the two half-sites on the A2.2-binding activity.

(A) Nucleotide sequence of the rat insulin II enhancer region from −139 to −113 bp. Underlined nucleotides are required for the binding of A2.2 factor. The del27.26 represents the sequence with deletion of two base-pairs (TT) at positions −127.126 bp, and Ins2 and Ins5 represent the sequence insertion of two or five base-pairs (GG or TTAAA respectively) between −126 and −125 bp in the −139 to −113 bp oligonucleotide. (B) HIT T-15 nuclear extract was incubated with radiolabelled −139 to −113 bp probe in the absence or presence of increasing amounts (5–50-fold) of indicated unlabelled competitor. Binding reactions were analysed by EMSA.

These results demonstrated that the nucleotides TGTTNGGNAACT represent the binding site of the A2.2 factor, which is distinct from the binding sites of the PDX-1 and Nkx2.2 factors, consistent with our earlier observation [38]. Interestingly, the A2.2-binding site, like the MafA-binding site, is composed of two half-sites separated by four central (core) base-pairs [38]. The core nucleotides of the A2.2-binding site and the insulin MARE element are markedly different. Substitution mutations in the MARE core nucleotides have no effect on the binding of MafA, while altering the distance between the two half-sites completely prevented binding [38]. In contrast, presence of a single guanine nucleotide in the A2.2 core region is essential for its binding, and minor alterations in the distance between the half-sites have a moderate effect on this process. These observations suggest that in comparison with MafA, the A2.2 factor has more flexibility in recognizing its binding site.

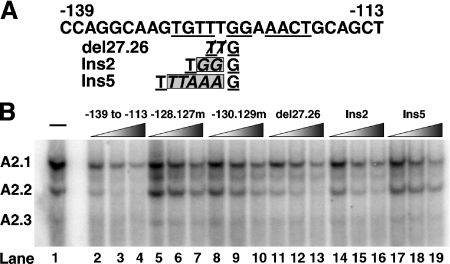

Construction and characterization of non-overlapping A2 and MARE elements

Our earlier study demonstrated that the rat insulin II enhancer region from −139 to −101 bp contained an overlapping A2/MARE element [38]. Hence, to construct non-overlapping elements, we synthesized a −139 to −101 bp oligonucleotide containing a 7 bp insert (CAAAACT) between nucleotides at the positions −120 and −119 bp (Figure 3A). Based on the experimentally determined DNA-binding sites of A2.2 (solid underline) and MafA (broken underline), the insertion of seven base-pairs should abolish the overlapping A2 site and at the same time create separated A2 and MARE (S.A2/MARE) elements. Furthermore, the insertion of seven base-pairs would position the separated A2 element on the opposite side of the double helix, thereby altering the ability of the bound factor to interact with MafA and other transcription factors. Thus the separated element should permit the analysis of overlapping and non-overlapping binding, and functional/physical interactions between these factors on regulating insulin gene expression. To test this, HIT T-15 nuclear extract was incubated with either S.A2/MARE or −139 to −101 bp probe, in the presence or absence of the indicated competitors (Figure 3B). Results from EMSA were identical for both probes; in the absence of any competitor, five distinct DNA-binding complexes could be seen (MafA, RIPE3b2, A2.1, A2.2 and A2.3). Addition of unlabelled wild-type −139 to −101 bp or S.A2/MARE oligonucleotides successfully competed for the binding of all five complexes. As shown previously, oligonucleotides with mutations that alter critical nucleotides in the overlapping region, which prevent the formation of MafA and RIPE3b2 complexes (−110.109m) or all five complexes (−122.121m) [38], did not compete for the formation of corresponding complexes with either the S.A2/MARE or −139 to 101 bp probe. Furthermore, an unlabelled oligonucleotide with mutations at the −114.113 bp, which are not critical for the formation of any of the five complexes, successfully competed for all DNA-binding complexes. These results demonstrate that the MafA and A2.2 factors can successfully bind to the oligonucleotide containing non-overlapping enhancer elements.

Figure 3. Construction and characterization of non-overlapping A2 and MARE elements.

(A) Schematic representation of the oligonucleotide sequence of wild-type rat insulin II enhancer region from 139 to 101 bp (−139 to −101) and non-overlapping A2 and MARE elements (S.A2/MARE) and its derivatives. Seven nucleotides (CAAAACT) in the grey box are inserted between nucleotides at positions −120 and −119 bp to construct non-overlapping S.A2/MARE elements. Nucleotides underlined in solid are essential for the binding of A2.2 factor, while those with a dashed underline are required for the binding of MafA. Two boxed nucleotides (AA) at 122 and 121 bp are essential for the binding of both MafA and A2.2 factors [38]. These two base-pairs were mutated (shown in boldface) to generate a separated oligonucleotide with mutation either in the A2 element (S.mA2/MARE) or in the MARE element (S.A2/mMARE). (B) HIT T-15 nuclear extract was incubated with either radiolabelled S.A2/MARE or −139 to −113 bp probe in the presence or absence of indicated unlabelled competitor, and the binding reactions were analysed by EMSA. Competitor oligonucleotides, −110.109m, −114.113m and −122.121m, represent oligonucleotides with mutations in the indicated base-pairs. The location of specific DNA-binding complexes has been indicated. (C) HIT T-15 nuclear extract was incubated with radiolabelled −139 to −113 bp probe in the presence or absence of indicated unlabelled competitors S.A2/MARE, S.mA2/MARE and S.A2/mMARE. Binding reactions were analysed by EMSA.

Next, we tested whether the A2.2 and MafA factors bound independently to their respective separated binding sites in the S.A2/MARE oligonucleotide. Competition analysis was performed with 50-fold excess of competitor oligonucleotides with mutations that selectively prevented binding of these factors to either the separated A2 or MARE elements (Figure 3C). Since mutations at positions −122.121 in the wild-type −139 to 101 oligonucleotide prevented the formation of all five complexes (see Figure 3B), nucleotides corresponding to the −122.121 bp were individually mutated in the separated A2 (S.mA2/MARE) and MARE (S.A2/mMARE) elements (see Figure 3A). If the addition of seven base-pairs results in the formation of separated elements, then S.mA2/MARE and the S.A2/mMARE would not compete for the formation of A2- and MARE-specific binding complexes respectively. However, if our design of the separated binding site did not abolish the overlapping site or resulted in the creation of a new overlapping site, then the presence of excess unlabelled S.mA2/MARE or S.A2/mMARE oligonucleotide would compete for the formation of all five complexes. HIT T-15 nuclear extract was incubated with the wild-type −139 to −101 bp probe in the presence or absence of various separated-element competitors. As shown in Figure 3(B), wild-type S.A2/MARE successfully competed for the binding of all five complexes. Furthermore, as expected from their design, S.mA2/MARE and S.A2/mMARE oligonucleotides competed for the MARE- and A2-binding factors respectively. These results clearly demonstrate successful construction of non-overlapping A2 and MARE elements, which can specifically bind A2.2 and MafA factors respectively.

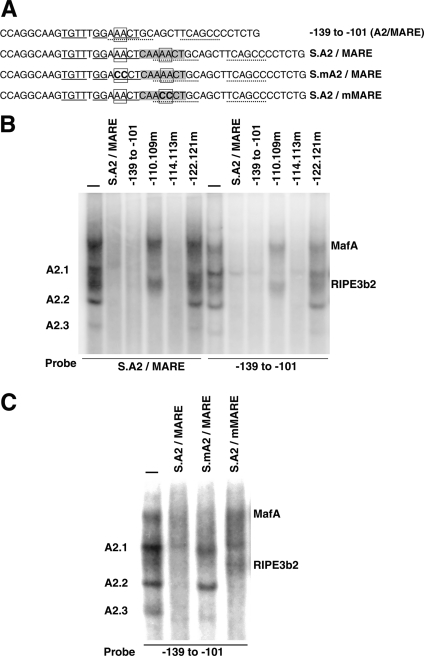

Overlapping organization of A2 and MARE elements is essential for maximal insulin gene expression

In our previous study, we demonstrated that the A2.2 and MafA factors, when bound to the overlapping binding site, co-operatively activated insulin gene expression [38]. Successfully designing an oligonucleotide with non-overlapping A2 and MARE elements (Figure 3) allowed us to test whether the overlapping organization is essential for in vivo co-operative activation of the insulin gene. In a wild-type rat insulin II luciferase reporter construct, −238 WT LUC, mutations corresponding to S.A2/MARE, S.mA2/MARE and S.A2/mMARE were constructed using a site-directed mutagenesis kit, as described previously in the Experimental section. Wild-type (−238 WT LUC) and the mutant insulin enhancer luciferase reporter constructs (new mutant constructs and those used in the earlier study [38], −110.109m LUC, −122.121m LUC and −125.124m LUC), were transfected into insulin-producing cell lines MIN-6 and HIT T-15. Luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were measured 48 h after transfection. Luciferase activity from insulin reporter constructs are presented relative to the activity of the −238 WT LUC construct (Figure 4).

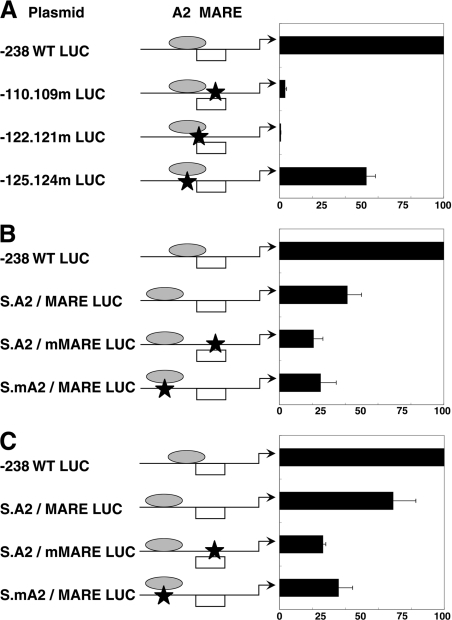

Figure 4. Effect of overlapping organization of A2 and MARE elements on the rat insulin II gene expression.

Schematic representation of rat insulin II LUC reporter constructs (−238 WT LUC) denotes the positions of A2 and MARE elements. MafA (open box) and the A2.2 factor (grey oval) are shown to depict overlapping and non-overlapping enhancer element organizations. Schematic representation of different reporter constructs −110.109m LUC, −122.121m LUC, −125.124m LUC, S.A2/MARE S.A2/mMARE and S.mA2/MARE is shown. Relative positions of each mutation (designated by a star) and the effect of these mutations on the binding of MafA and A2.2 factors are depicted. Equal amounts of wild-type and mutant plasmids were transfected into the MIN-6 (A, B) or HIT T-15 (C) cell lines. Luciferase activity was determined 48 h after transfection and was normalized to β-galactosidase (internal control) activity. Results are presented as mean percentage of the relative luciferase activity of the −238 WT LUC ±S.E.M. for at least three independent experiments.

Consistent with our previous results in HIT T-15 cells [38], loss of MafA binding in transfected MIN-6 cells results in significant inhibition of insulin gene expression (95% or 20-fold inhibition), whereas the mutation inhibiting binding of the A2.2 factor shows approx. 50% or 2-fold inhibition of insulin gene expression (Figure 4A). Mutating nucleotides at positions −122 and −121 bp, which prevents binding of both factors, almost completely (99% or 100-fold) inhibited insulin gene expression, and this inhibition was significantly greater (P=0.05) than the selective loss of MafA binding (−110.109m LUC). These results are consistent with our earlier conclusion [38] that overlapping binding of both A2.2 and MafA factors results in co-operative activation (approximately twice the activity of individual factors) of the insulin gene. The importance of the overlapping binding sites is clearly demonstrated by the results of transient transfection experiments in MIN-6 cells (Figure 4B) and HIT T-15 cells (Figure 4C). In comparison with the wild-type (−238 WT LUC) construct containing overlapping elements, luciferase activity from the separated A2/MARE construct was inhibited by approx. 60% in MIN-6 cells and approx. 40% in HIT T-15 cells. Interestingly, the mutation in MARE (S.A2/mMARE) or A2 (S.mA2/MARE) elements resulted in the inhibition of insulin gene expression by 80 and 75% in MIN-6 cells and 75 and 65% in HIT T-15 cells respectively. Thus a non-overlapping organization of A2/MARE elements results in approx. 50% reduction in the insulin gene expression. Our results also demonstrate that the enhancer element organization differentially affected A2.2- and MafA-mediated transcriptional activation. As seen in Figure 4 and in our previous study [38], mutating the A2.2-binding site in the overlapping enhancer elements (−125.124m LUC, 50% inhibition; Figure 4A) or in a non-overlapping element (S.mA2/MARE LUC, from 60 to 75% inhibition in MIN-6 cells and from 40 to 65% in HIT T-15 cells), inhibits insulin gene expression to a similar extent (nearly 40–50% inhibition) when compared with the corresponding wild-type reporter constructs. It is important to note that the A2.2-binding site in the non-overlapping element, compared with the overlapping element, is on the opposite side of the double helix. Taken together, these observations suggest that the A2.2 factor, when bound to the opposite side of the helix, can still interact with factors required for its activity, such as basal transcription machinery. Thus such a binding of A2.2 factor on the opposite side of the helix may selectively affect its interactions with MafA, in turn affecting the ability of MafA to activate insulin gene expression. This inference was substantiated by the observations that insulin gene expression from −110.109m LUC (overlapping) construct was inhibited by approx. 95% (Figure 4A), while that from S.A2/mMARE showed significantly less inhibition (∼50%, from 60 to 80% inhibition in MIN-6 cells and from 40 to 75% in HIT T-15 cells) when compared with the corresponding non-overlapping (S.A2/MARE LUC) wild-type enhancer constructs (Figures 4B and 4C).

Results presented in Figures 3 and 4 demonstrate that MafA can effectively bind the non-overlapping MARE site, and thus should effectively interact with at least the basal transcription machinery and BETA2/NeuroD1 bound to the E1 element. Yet we observed a reduction in the MafA-mediated transcriptional activation from non-overlapping enhancer elements. Addition of seven base-pairs to separate the two elements could alter interactions between MafA and factors binding 3′ to the A2-MARE region, e.g. PDX-1 binding to the A3 element, resulting in the reduced activation of gene expression. However, as stated above, mutating A2 elements in the overlapping or separated element organizations (Figure 4A, [38]) results in a similar (2-fold) reduction in co-operative activation of the insulin gene expression. This observation suggests that the interaction between A2.2 and MafA is responsible for this 2-fold reduction in the insulin gene expression. Thus, if the loss of interactions between MafA and other insulin gene transcription factors is responsible for the reduced co-operative activation in the separated construct, then these interactions, even in the overlapping element organization, are dependent on the interaction between A2.2 and MafA. Transcription factors interact with other transcription factors and cofactors, which in turn determines their ability to activate and their level of activation (activation potential). Our results would suggest that interaction between MafA and A2.2 is important for achieving maximal activation potential of the MafA factor.

Overlapping A2/MARE enhancer element organization affects the transcriptional activation potential of MafA

Our results demonstrate that insulin reporter constructs with overlapping or non-overlapping A2/MARE elements differentially activated insulin gene expression. Since the true identity of A2.2 factor is not known, it is not possible to test whether MafA and A2.2 factors physically interact with each other. However, we can test if the overlapping organization affects the function of these factors. To test the molecular mechanism regulating this process, we transfected increasing amounts of −238 WT LUC and S.A2/MARE LUC reporter constructs into MIN-6 cells (Figure 5A). As can be seen in Figure 5(A), luciferase activity from the separated A2/MARE construct was significantly lower at all DNA concentrations compared with that of the −238 WT LUC construct. Interestingly, luciferase activity from both constructs appears to reach saturation at a similar rate in cells transfected with higher concentrations of reporter constructs. There are two possible explanations for this observation: (i) binding affinity of MafA is reduced for the separated A2/MARE elements or (ii) MafA bound to the separated MARE element has reduced transcriptional activation potential. In vitro and in vivo approaches were used to test whether the reduction in insulin gene expression from the separated enhancer element construct was due to the reduction in binding affinity of MafA for the MARE element. In the in vitro approach, competition analysis was performed to determine directly the effect of enhancer element organizations (overlapping or non-overlapping) on the binding activity of MafA. HIT T-15 nuclear extract was incubated with radiolabelled −139 to −101 bp probe or S.A2/MARE probe, in the presence or absence of increasing amounts of unlabelled S.A2/MARE oligonucleotide as a competitor. Results from the competition analyses (Figure 5B) demonstrate that the S.A2/MARE competitor effectively competed for the binding of the factors to the overlapping as well as non-overlapping A2/MARE probes. Furthermore, increasing concentrations of both competitors competed at similar rates for the MafA factor (26.8±3.4, 18.5±3.9 and 9.0±2.4% and 24.2±5.7, 19.8±4.4 and 9.6±3.0% for overlapping and non-overlapping competitors respectively), demonstrating that the binding affinity of MafA for both overlapping and non-overlapping MARE element organizations was not significantly different (P value from 0.2 to 0.44).

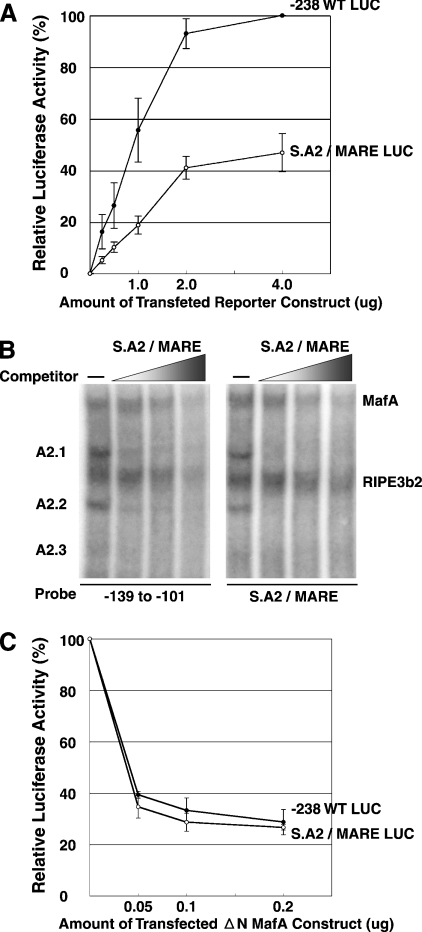

Figure 5. Effect of A2 and MARE element organizations on DNA-binding affinity and transcriptional activation of MafA.

(A) Transcriptional activation mediated by the −238 WT LUC and the separated A2/MARE construct at various DNA concentrations. Indicated amounts of −238 WT LUC and S.A2/MARE LUC reporter constructs were transfected into MIN-6 cells. The results are presented as mean percentage of relative luciferase activity from cells transfected with 4 μg of the −238 WT LUC ±S.E.M. for at least three independent experiments. (B) Effect of enhancer element organizations on the binding activity of MafA. HIT T-15 extract was incubated with radiolabelled −139 to −101 bp probe or S.A2/MARE probe in the absence or presence of increasing amounts (5–50-fold) of unlabelled S.A2/MARE oligonucleotide as competitor, and reactions were analysed by EMSA. Positions of MafA, RIPE3b2, A2.1, A2.2 and A2.3 are indicated. (C) Effect of dominant-negative MafA (ΔN MafA) on MafA-mediated activation from overlapping and non-overlapping MARE elements. The −238 WT LUC and S.A2/MARE LUC reporter constructs (1 μg each) were transfected into MIN-6 cells with indicated amounts of ΔN MafA construct lacking the N-terminal activation domain [13]. The rate of inhibition of gene expression from each construct is presented as mean percentage relative to the luciferase activity without ΔN MafA construct ±S.E.M. for at least three independent experiments.

A dominant-negative MafA derivative that lacks the N-terminal activation domain (ΔN MafA) was used to understand further the difference in MafA-mediated activation of gene expression from reporter constructs with overlapping and non-overlapping MARE element organizations. The ΔN MafA has an intact protein–protein interaction and DNA-binding domain and thus can dimerize with the endogenous MafA. Hence, homodimers of ΔN MafA, as well as the heterodimer of MafA–ΔN MafA, should bind the insulin MARE with the same affinity as the wild-type MafA [13]. Co-transfection of MIN-6 cells with increasing amounts of ΔN MafA and reporter constructs with overlapping or non-overlapping enhancer elements resulted in significant inhibition of luciferase expression from both constructs (Figure 5C). Although the reporter construct with non-overlapping A2/MARE organization is half as active as the wild-type overlapping element construct (Figures 4B and 5A), the rate of inhibition of gene expression from both constructs in the presence of ΔN MafA remained the same. This observation, together with the results presented in Figure 5(B), suggests that similar amounts of endogenous MafA bind the separated and overlapping A2/MARE elements. Nevertheless, the resulting activation of insulin gene expression from the S.A2/MARE construct was inhibited by approx. 50% (Figures 4B and 5A). Based on these observations, we suggest that the binding of MafA to non-overlapping A2/MARE elements results in a reduction in the activation potential of this factor. Our results also show that the overlapping enhancer element organization is not essential for the binding of either the A2.2 or MafA factor and for A2.2-mediated transcriptional activation. Yet our results demonstrate that maximal MafA-mediated transcriptional activation of insulin gene is dependent on the enhancer element organizations, and binding of transcription factors like A2.2 to an overlapping enhancer element, which is critical for its activation potential. We are now in the process of determining the molecular mechanisms involved in regulating the activation potential of MafA.

Functional/physical interaction between MafA and A2.2 factor leads to nearly 2-fold inhibition of MafA function. Increasing evidence suggests that in a complex metabolic disease like diabetes, moderate changes in gene expression may have significant physiological impact [42–44]. Moderate changes in the level of transcription factors PDX-1 and BETA2 have been linked with development of diabetes and loss of β-cell function [23,28,45–47], underscoring the importance of such moderate 2-fold changes in the level/activity of key insulin gene transcription factors on β-cell function. As increasing evidence supports the role of MafA in β-cell function, and possibly in pancreatic development, our results identify a novel regulatory step that may play an important role in controlling these processes.

The A2–MARE overlapping site does not influence the binding activities of these factors, but it affects their activation potential. Our results demonstrate that the maximal activation potential of MafA is dependent on the proper context between MARE and surrounding transcription-factor-binding sites. This observation provides a plausible explanation for the discrepancy in the transforming ability and transcriptional activation potential of MafA [48,49]. Comparison of these processes for chicken cMaf, MafB and MafA factors demonstrated that MafA had a higher transforming ability than the other two factors [48,49]; yet MafB and cMaf were significantly better at activating reporter gene expression from a multimerized MARE construct than MafA [48,49]. Interestingly, MafA transactivated the αA-crystallin promoter as effectively as MafB and cMaf [49]. Based on our results, we suggest that the inability of MafA to activate gene expression from a multimerized MARE construct may result from the lack of a binding site for accessory factors such as A2.2, while the ability of MafA to activate expression from the large αA-crystallin promoter would imply that the MARE element and the binding sites for such accessory factors are in proper context in the endogenous promoter. However, it is important to note that nucleotides outside the classical MARE element [TGC(N)6–7GCA] are required for the binding of MafA [38], and they may have a role in differential activation of MARE and αA-crystallin promoter constructs by MafA. Based on these results, we suggest that mere binding of MafA alone to a MARE element is not sufficient for maximal activation of MafA-mediated insulin gene expression. Increased activation potential of MafA by the binding of other transcription factors, such as A2.2, near (overlapping) the MafA-binding site may represent a critical mechanism by which MafA can discriminate its downstream targets from those of other large Maf factors. Thus our results suggest an important role of the transcription factor A2.2 in regulating expression of true downstream targets of MafA. Furthermore, due to its ability to modulate MafA's activation potential, the A2.2 factor, like MafA, may play a role in regulating pancreatic development and β-cell function. Identification of the molecular mechanisms regulating the activation potential of MafA will result in a clearer understanding of the roles of MafA and A2.2 in these processes; we are currently pursuing these objectives.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr J.-I. Miyazaki (Osaka University) for providing MIN-6 cells, Samit Shah and Jon Rud for technical assistance, and Samit Shah and Rikke Dodge (Joslin Diabetes Center) for suggestions and help with preparation of this paper. This study was supported in part by a National Institutes of Health grant R01DK060127 and a research grant from American Diabetes Association to A.S. We acknowledge the services provided by the media core of Joslin Diabetes Center (supported by the Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center grant NIH DK-36836).

References

- 1.German M. S., Moss L. G., Wang J., Rutter W. J. The insulin and islet amyloid polypeptide genes contain similar cell-specific promoter elements that bind identical β-cell nuclear complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1992;12:1777–1788. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.4.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peshavaria M., Gamer L., Henderson E., Teitelman G., Wright C. V. E., Stein R. XIHbox 8, an endoderm-specific Xenopus homeodomain protein, is closely related to a mammalian insulin gene transcription factor. Mol. Endocrinol. 1994;8:806–816. doi: 10.1210/mend.8.6.7935494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohlsson H., Thor S., Edlund T. Novel insulin promoter- and enhancer binding proteins that discriminate between pancreatic A- and B-cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 1991;5:897–904. doi: 10.1210/mend-5-7-897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boam D. S. W., Docherty K. A tissue-specific nuclear factor binds to multiple sites in the human insulin-gene enhancer. Biochem. J. 1989;264:233–239. doi: 10.1042/bj2640233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shieh S.-Y., Tsai M.-J. Cell-specific and ubiquitous factors are responsible for the enhancer activity of the rat insulin II gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:16708–16714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karlsson O., Edlund T., Barnett Moss J., Rutter W. J., Walker M. D. A mutational analysis of the insulin gene transcriptional control region: expression in beta cells is dependent on two related sequences within the enhancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1987;84:8819–8823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.8819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crowe D. T., Tsai M.-J. Mutagenesis of the rat insulin II 5′-flanking region defines sequences important for expression in HIT cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1989;9:1784–1789. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.4.1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohlsson H., Karlsson K., Edlund T. IPF1, a homeodomain-containing transactivator of the insulin gene. EMBO J. 1993;12:4251–4259. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06109.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leonard J., Peers B., Johnson T., Ferreri K., Lee S., Montminy M. R. Characterization of somatostatin transactivating factor-1, a novel homeobox factor that stimulates somatostatin expression in pancreatic islet cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 1993;7:1275–1283. doi: 10.1210/mend.7.10.7505393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller C. P., McGehee R. E., Habener J. F. IDX-1: a new homeodomain transcription factor expressed in rat pancreatic islets and duodenum that transactivates the somatostatin gene. EMBO J. 1994;13:1145–1156. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06363.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.German M. S., Blanar M. A., Nelson C., Moss L. G., Rutter W. J. Two related helix-loop-helix proteins participate in separate cell-specific complexes that bind the insulin enhancer. Mol. Endocrinol. 1991;5:292–299. doi: 10.1210/mend-5-2-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naya F. J., Stellrecht C. M. M., Tsai M.-J. Tissue-specific regulation of the insulin gene by a novel basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1009–1019. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.8.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olbrot M., Rud J., Moss L. G., Sharma A. Identification of beta-cell-specific insulin gene transcription factor RIPE3b1 as mammalian MafA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:6737–6742. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102168499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kataoka K., Han S. I., Shioda S., Hirai M., Nishizawa M., Handa H. MafA is a glucose-regulated and pancreatic beta-cell-specific transcriptional activator for the insulin gene. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:49903–49910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206796200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuoka T. A., Zhao L., Artner I., Jarrett H. W., Friedman D., Means A., Stein R. Members of the large Maf transcription family regulate insulin gene transcription in islet beta cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:6049–6062. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.17.6049-6062.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma A., Fusco-DeMaine D., Henderson E., Efrat S., Stein R. The role of the insulin control element and RIPE3b1 activators in glucose-stimulated transcription of the insulin gene. Mol. Endocrinol. 1995;9:1468–1476. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.11.8584024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma A., Stein R. Glucose-induced transcription of the insulin gene is mediated by factors required for B-cell-type-specific expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:871–879. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.2.871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacFarlane W. M., Read M. L., Gilligan M., Bujalska I., Docherty K. Glucose modulates the binding activity of the B-cell transcription factor IUF1 in a phosphorylation-dependent manner. Biochem. J. 1994;303:625–631. doi: 10.1042/bj3030625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melloul D., Ben-Neriah Y., Cerasi E. Glucose modulates the binding of an islet-specific factor to a conserved sequence within the rat I and the human insulin promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:3865–3869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.3865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.German M. S., Wang J. The insulin gene contains multiple transcriptional elements that respond to glucose. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:4067–4075. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.6.4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma A., Olson L. K., Robertson R. P., Stein R. The reduction of insulin gene transcription in HIT-T15 β cells chronically exposed to high glucose concentration is associated with the loss of RIPE3b1 and STF-1 transcription factor expression. Mol. Endocrinol. 1995;9:1127–1134. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.9.7491105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zangen D. H., Bonner-Weir S., Lee C. H., Latimer J. B., Miller C. P., Habener J. F., Weir G. C. Reduced insulin, GLUT2, and IDX-1 in B-cells after partial pancreatectomy. Diabetes. 1997;46:258–264. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.2.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jonas J.-C., Sharma A., Hasenkamp W., Ilkova H., Patane G., Laybutt R., Bonner-Weir S., Weir G. C. Chronic hyperglycemia triggers loss of pancreatic β cell differentiation in an animal model of diabetes. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:14112–14121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.14112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jonsson J., Carlsson L., Edlund T., Edlund H. Insulin-promoter-factor 1 is required for pancreas development in mice. Nature (London) 1994;371:606–609. doi: 10.1038/371606a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Offield M. F., Jetton T. L., Labosky P., Ray M., Stein R., Magnuson M., Hogan B. L. M., Wright C. V. E. PDX-1 is required for pancreatic outgrowth and differentiation of the rostral duodenum. Development. 1996;122:983–985. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.3.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahlgren U., Jonsson J., Edlund H. The morphogenesis of the pancreatic mesenchyme is uncoupled from that of the pancreatic epithelium in IPF1/PDX1-deficient mice. Development. 1996;122:1409–1416. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.5.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naya F. J., Huang H. P., Qiu Y., Mutoh H., DeMayo F. J., Leiter A. B., Tsai M. J. Diabetes, defective pancreatic morphogenesis, and abnormal enteroendocrine differentiation in BETA2/neuroD-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2323–2334. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.18.2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dutta S., Bonner-Weir S., Wright C., Montminy M. Altered glucose tolerance in PDX-1 mice. Nature (London) 1998;392:560. doi: 10.1038/33311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stoffers D. A., Ferrer J., Clarke W. L., Habener J. F. Early-onset type-II diabetes mellitus (MODY4) linked to IPF1. Nat. Genet. 1997;17:138–139. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malecki M. T., Jhala U. S., Antonellis A., Fields L., Doria A., Orban T., Saad M., Warram J. H., Montminy M., Krolewski A. S. Mutations in NEUROD1 are associated with the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Genet. 1999;23:323–328. doi: 10.1038/15500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ogino H., Yasuda K. Induction of lens differentiation by activation of a bZIP transcription factor, L-Maf. Science. 1998;280:115–118. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ring B. Z., Cordes S. P., Overbeek P. A., Barsh G. S. Regulation of mouse lens fiber cell development and differentiation by the Maf gene. Development. 2000;127:307–317. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.2.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benkhelifa S., Provot S., Nabais E., Eychene A., Calothy G., Felder-Schmittbuhl M.-P. Phosphorylation of MafA is essential for its transcriptional and biological properties. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:4441–4452. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.14.4441-4452.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao L., Cissell M. A., Henderson E., Colbran R., Stein R. The RIPE3b1 activator of the insulin gene is composed of a protein(s) of approximately 43 kDa, whose DNA binding activity is inhibited by protein phosphatase treatment. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:10532–10537. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.10532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.German M., Ashcroft S., Docherty K., Edlund H., Edlund T., Goodison S., Imura H., Kennedy G., Madsen O., Melloul D., et al. The insulin gene promoter: a simplified nomenclature. Diabetes. 1995;44:1002–1004. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.8.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boam D. S. W., Clark A. R., Docherty K. Positive and negative regulation of the human insulin gene by multiple trans-acting factors. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:8285–8296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tomonari A., Yoshimoto K., Tanaka M., Iwahana H., Miyazaki J., Itakura M. GGAAAT motifs play a major role in transcriptional activity of the human insulin gene in a pancreatic islet beta-cell line MING. Diabetologia. 1996;39:1462–1468. doi: 10.1007/s001250050599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harrington R. H., Sharma A. Transcription factors recognizing overlapping C1-A2 binding sites positively regulate insulin gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:104–113. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008415200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blank V., Andrews N. C. The Maf transcription factors: regulators of differentiation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1997;22:437–441. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matsushima-Hibiya Y., Nishi S., Sakai M. Rat Maf-related factors: the specificities of DNA binding and heterodimer formation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998;245:412–418. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dlakic M., Grinberg A. V., Leonard D. A., Kerppola T. K. DNA sequence-dependent folding determines the divergence in binding specificities between Maf and other bZIP proteins. EMBO J. 2001;20:828–840. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.4.828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patti M. E., Butte A. J., Crunkhorn S., Cusi K., Berria R., Kashyap S., Miyazaki Y., Kohane I., Costello M., Saccone R., et al. Coordinated reduction of genes of oxidative metabolism in humans with insulin resistance and diabetes: potential role of PGC1 and NRF1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:8466–8471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1032913100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yechoor V. K., Patti M. E., Ueki K., Laustsen P. G., Saccone R., Rauniyar R., Kahn C. R. Distinct pathways of insulin-regulated versus diabetes-regulated gene expression: an in vivo analysis in MIRKO mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:16525–16530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407574101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mootha V. K., Lindgren C. M., Eriksson K.-F., Subramanian A., Sihag S., Lehar J., Puigserver P., Carlsson E., Ridderstrale M., Laurila E., et al. PGC-1α-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat. Genet. 2003;34:267–273. doi: 10.1038/ng1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andreassen O. A., Dedeoglu A., Stanojevic V., Hughes D. B., Browne S. E., Leech C. A., Ferrante R. J., Habener J. F., Beal M. F., Thomas M. K. Huntington's disease of the endocrine pancreas: insulin deficiency and diabetes mellitus due to impaired insulin gene expression. Neurobiol. Dis. 2002;11:410–424. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakajima-Nagata N., Sugai M., Sakurai T., Miyazaki J., Tabata Y., Shimizu A. Pdx-1 enables insulin secretion by regulating synaptotagmin 1 gene expression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;318:631–635. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brissova M., Shiota M., Nicholson W. E., Gannon M., Knobel S. M., Piston D. W., Wright C. V., Powers A. C. Reduction in pancreatic transcription factor PDX-1 impairs glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:11225–11232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111272200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nishizawa M., Kataoka K., Vogt P. K. MafA has strong cell transforming ability but is a weak transactivator. Oncogene. 2003;22:7882–7890. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoshida T., Yasuda K. Characterization of the chicken L-Maf, MafB and c-Maf in crystallin gene regulation and lens differentiation. Genes Cells. 2002;7:693–706. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2002.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]