Abstract

Recombinant human nerve growth factor (rhNGF) is regarded as the most promising therapy for neurodegeneration of the central and peripheral nervous systems as well as for several other pathological conditions involving the immune system. However, rhNGF is not commercially available as a drug. In this work, we provide data about the production on a laboratory scale of large amounts of a rhNGF that was shown to possess in vivo biochemical, morphological, and pharmacological effects that are comparable with the murine NGF (mNGF), with no apparent side effects, such as allodynia. Our rhNGF was produced by using conventional recombinant DNA technologies combined with a biotechnological approach for high-density culture of mammalian cells, which yielded a production of ≈21.5 ± 2.9 mg/liter recombinant protein. The rhNGF-producing cells were thoroughly characterized, and the purified rhNGF was shown to possess a specific activity comparable with that of the 2.5S mNGF by means of biochemical, immunological, and morphological in vitro studies. This work describes the production on a laboratory scale of high levels of a rhNGF with in vitro and, more important, in vivo biological activity equivalent to the native murine protein.

Keywords: mammalian cells, miniPerm system, neurotrophic activity

Recombinant proteins are promising for the treatment of many neurodegenerative and inflammatory diseases. Compelling basic and preclinical evidence points to neurotrophic and neurokine factors as potential candidates for preventing biochemical, pharmacological, and molecular deficits of several pathologies that lack effective therapies (reviewed in ref. 1). Some of these growth factors, including nerve growth factor (NGF) (2) have already been tested in preclinical and clinical trials. Indeed, murine NGF (mNGF) has been used successfully for human corneal and pressure ulcers (3-5), as well as vasculite (6) and crush syndrome (7), whereas recombinant human NGF (rhNGF) was shown to be effective in rodent and primate models of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (8) and Alzheimer's disease (9, 10), as well in phase-II clinical trials of peripheral neuropathies (11). These findings are particularly interesting considering that NGF, which was identified originally as a potent neurotrophic factor for sympathetic and sensory neurons (12), was found to be essential also for basal forebrain cholinergic neurons (reviewed in ref. 13). Studies also showed that many other mammalian cells are NGF-responsive, including cells of the hemopoietic immune system (14), and, for some pathologies, symptoms also correlated with alterations of NGF serum levels (15, 16).

All of this evidence supports the pharmacological interest for NGF as a useful therapeutic agent to promote the regression of many pathological conditions (1). However, the clinical efficacy of NGF has been obtained with the 2.5S mNGF (3-7), which cannot be used for human therapy on large scale. Therefore, for clinical trials and therapeutic purposes, large amounts of the recombinant human protein are required, possibly produced at reasonable cost and in sufficient amounts.

The technology of rhNGF preparation is not complex; however, the biological activity of β-NGF relies on the formation of three disulfide bonds and a cysteine knot within two β-chains of 120 aa each after cleavage of the signal and propeptide sequences from a larger precursor molecule (17-19). Several attempts have been made to produce rhNGF in different systems, including Saccharomyces cerevisiae (20, 21) and Escherichia coli inclusion bodies (22, 23), as well as insect (24, 25) and mammalian (26) cells. However, most of the available studies with rhNGF have been carried out in vitro, and the available evidence in vivo indicates that the action of rhNGF in human peripheral neuropathies was not comparable with the effect of mNGF (27).

Here, we present data regarding the production of a rhNGF that is biologically active in vitro and exerts in vivo biochemical, pharmacological, and structural effects comparable with the mNGF. Our data, by providing a biotechnological approach for production of large amounts of biologically active rhNGF in human cells, open up the possibilities of using this recombinant neurotrophin for clinical trials and therapeutic applications.

Materials and Methods

Cell Cultures. HeLa Tet-Off cells (Clontech) were maintained in DMEM (Sigma) supplemented with 10% FBS (Sigma), 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 200 μg/ml G418 (Sigma) in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air/5% CO2 at 37°C. PC12 cells and PC12 (clone 615) (28) stably overexpressing trkA (kindly provided by M. V. Chao, New York University, New York) were grown as described in ref. 29. Treatments of PC12 cells were performed in DMEM supplemented with 0.5% FBS and 1% heat-inactivated horse serum (Sigma).

Dorsal root ganglia (DRG) were dissected from 8-day-old chick embryos and placed into Hepes-buffered saline solution. Ganglia were then cultured onto poly-l-lysine (1%) precoated dishes in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, and penicillin-streptomycin. Treatments with rhNGF or 2.5S mNGF (Promega) were carried out immediately after plating.

Plasmid Construction. The cDNA of human NGF (exon 3) was cloned by PCR using a human hippocampal cDNA library (Clontech) and the nucleotide sequence published by Ullrich et al. (17). The cDNA fragment was inserted into a pCR2.1-TOPO-TA vector (Invitrogen) and then subcloned into a pcDNA3.1 expression vector (Invitrogen) at the HindIII-XhoI sites of the polylinker region. The pTRE-hNGF construct was generated by digestion of the NGF coding sequence from pcDNA-hNGF at SpeI/XbaI sites, followed by insertion at the unique XbaI site in the MCS of the pTRE plasmid (Clontech). All constructs were analyzed by restriction and sequence analyses to verify the correct sequence and orientation of the fragment.

DNA Transfections and Production of Stable Transfectants. Transient transfection of HeLa Tet-Off cells (Clontech) was carried out by using the Lipofectamine reagent (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions, and recombinant protein expression was evaluated after 48 h on cell lysates and culture medium.

Stable transfectants were obtained by using the calcium phosphate precipitation technique, as described in ref. 29. HeLa Tet-Off cells were cotransfected with the pTRE-hNGF expression vector and the selection vector pTK-Hyg carrying the hygromycin resistance gene (10:1, according to the manufacturer's instructions). Double-stable transfectants were selected by adding 400 μg/ml hygromycin B (Sigma).

Laboratory-Scale Production of rhNGF in Minibioreactors. Minibioreactor systems for adherent cells (miniPERM, Greiner Bio-One, Nurtingen, Germany) were used for high-density cell cultures and laboratory-scale production of rhNGF. In the miniPERM, hNGF-HeLaTetOff cells (≈8 × 106) were cultured in DMEM containing 5% FBS. Medium from the production module was harvested every 24-48 h and replaced with fresh medium, whereas medium in the nutrient module was changed every 5 days. Cultures in the miniPERMs were maintained for up to 20 days, and rhNGF was partially purified by using a modification of the procedure described in ref. 25. Briefly, collected media were pooled, dialyzed against 25 mM 3-(N-morpholino)-2-hydroxypropanesulfonic acid (pH 7.0), and applied on a ion-exchange column HiTrap SP-Sepharose FastFlow (Amersham Biosciences) on an FPLC system (Amersham Biosciences), followed by a second passage on a hydrophobic column HiTrap Phenyl Sepharose FF (Amersham Biosciences). At this point, the purification degree was ≈1,000-fold of the initial product.

Analysis of rhNGF by Western Blotting. Cell lysates were prepared by detergent lysis method. Briefly, cells were washed and scraped in ice-cold PBS and resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 8.0/137 mM NaCl/1% Nonidet-P40/10% glycerol/1 mM DTT/2 mM PMSF/0.1 μg/ml leupeptin/5 μg/ml aprotinin). After a 20-min incubation on ice, cellular debris were pelleted by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Protein concentration was determined by the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad).

Cell lysates (5 μg total protein) or culture medium (5 μl of 1:10 dilution) were dissolved in loading buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 6.8/2% SDS/100 mM DTT/10% glycerol/0.1% bromophenol blue), separated on 12% SDS/PAGE gels, and transferred to nitrocellulose (Schleicher & Schüll). After blocking with 5% nonfat milk in TBST buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.5/150 mM NaCl/0.2% Tween 20), blots were probed overnight at 4°C with anti-NGF IgG (H-20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in TBST, followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 1 h at room temperature. Detection was obtained by the enhanced chemiluminescence system (ECL, Amersham Biosciences). Quantitation was performed by densitometric analysis of the bands (image, Scion, Frederick, MD) and plotting values on a standard curve with increasing amounts of 2.5S mNGF (Promega) loaded on the same gel.

In Vivo Studies. To investigate the in vivo activity, murine and rhNGF were injected in newborn mice at a dose of 5 μg per g of body weight daily for 5 consecutive days. Control mice were injected with the same amount of cytochrome c (CY), a molecule with similar physicochemical properties of NGF but lacking its biological activity. On day 6, mice were killed, and superior cervical ganglia (SCG) and cutaneous tissues of NGFs treated and untreated mice were dissected out, fixed in 4% paraformaldheyde in phosphate buffer, stained with toluidine blue, and mounted in toto for macroscopic examination. Ganglia and cutaneous tissues then were sectioned and stained with toluidine blue, and cell morphology and distribution were examined. Eye bulb and cutaneous tissues also were used to evaluate the effect of NGFs on trkA and substance P (SP) expression.

Determination of trkA Protein and Phosphorylation. Skin tissues (each 0.1 g) were homogenized in sample buffer (10 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.6/0.25 M sucrose/0.1 M NaCl/1 mM EDTA/1 mM PMSF) and centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Total proteins (30 μg) were dissolved in loading buffer, separated on 12.5% SDS/PAGE, and transferred to poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF). Membranes were probed for 2 h at room temperature with anti-trkA Ab (763; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by 1 h of incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling Technologies). Detection was obtained by the enhanced chemiluminescence system, and β-actin bands were used as internal control for differences in sample loading.

Immunoblotting analysis of trkA phosphorylation was carried out as described in ref. 29. Briefly, cells were exposed for 5 min to rhNGF or 2.5S mNGF (Promega), washed, and lysed at 4°C in 1 ml of radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5/150 mM NaCl/1% Nonidet P-40/0.5% sodium deoxycholate/0.1% SDS/1 mM DTT) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Lysates (300 μg of total proteins) were incubated overnight at 4°C with 2 μg of anti-pan-trk IgG (C-14, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by precipitation with protein A-Sepharose (Sigma) for an additional 2 h at 4°C. After washing, immunocomplexes were resuspended in loading buffer, separated on 7.5% SDS/PAGE, and transferred to nitrocellulose. Blots were probed overnight at 4°C with either a mouse anti-p-trkA mAb (E-6, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or an anti-p-Tyr mAb (PY99, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 1 h at room temperature. Detection of p-trkA was carried out by using the enhanced chemiluminescence system.

Analysis of SP mRNA by RT-PCR and ELISA. Total RNA was extracted from skin tissues (0.1 g each) by using the TRIzol reagent (GIBCO), and SP mRNA levels were measured by using a standardized RT-PCR method as described in ref. 30. cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg of total RNA by using 200 units of Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MLV) reverse transcriptase (Promega) in a 20-μl mixture containing 50 mM Tris·Cl (pH 8.3), 75 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM DTT, 250 ng of oligo(dT) 12-18 primer, 0.5 units of RNasin, and 0.5 mM dNTP at 42°C for 1 h. PCR amplification was carried out in a 50-μl reaction containing 5 μl of cDNA, 20 mM dNTPs, 0.15 mM MgCl2, 0.25 units of TaqDNA polymerase (Promega), 2.5 pmol of SP primers (5′-GAACTGCTGAGGCTTGGGTC-3′ and 5′-AAAATCCTCGTGGCCGTGGC-3′) (GenBank accession no. X54469), and 1 pmol of β-actin primers (5′-ACGAGGCCCAGAGCAAGAGA-3′ and 5′-ACTTGCGCTCAGGAGGAGCA-3′) (GenBank accession no. X00351). PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 2% agarose gel and ethidium bromide staining.

Biotinylated primers were used for detection of SP mRNA by ELISA. Microplates were coated with 50 μg/ml avidin (Sigma) in 15 mM Na2CO3/35 mM NaHCO3 (pH 9.6) for 2 h at 37°C. After blocking, avidin-coated wells were incubated with biotinylated PCR products for 1 h at room temperature. DNA was denatured with 0.25 M NaOH, followed by hybridization at 42°C for 2 h with 4 pmol/ml digoxygenin (DIG)-labeled probes for SP (5′-CTCTGCAGAAGATGCTCAAAGGGCTCCGGC-3′) and β-actin (5′-AGGATCTTCATGAGGTAGTCAGTCAGGTCC-3′) in DIG Easy hybridization buffer (Boehringer Mannheim). After incubation with anti-DIG peroxidase-coupled Ab (Boehringer Mannheim) the reaction was developed by 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine. The amount of amplified products was measured with OD at 450 and 690 nm (ELISA Reader 5000, Dynatech), and β-actin was used to normalize for differences between samples.

Results and Discussion

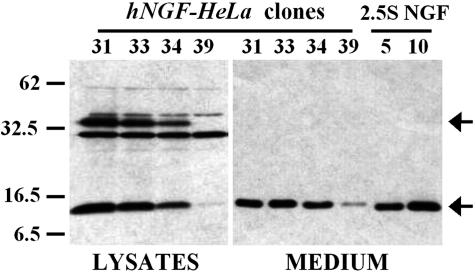

Production of rhNGF in Human Cells. Production of high amounts of the recombinant human protein is the foremost requirement for pharmacological applications of NGF. For this purpose, we prepared the pTRE-hNGF construct, which contained the whole exon 3 of the gene, including the sequence for mature NGF and the prepro sequence that is necessary for processing and secretion of the recombinant protein. The production of correctly processed rhNGF was first tested by transient transfection of HeLa Tet-Off cells. Western blot analysis of cell lysates and culture medium revealed a band corresponding to the 2.5S mNGF, whereas no NGF was detected in cells transfected with the empty vector (Mock) (data not shown).

Production of the recombinant protein was then obtained by stably transfecting the HeLa Tet-Off cells, as described in Materials and Methods. Several clones were isolated, and levels of rhNGF production and secretion were analyzed by Western blot of both cell lysates and conditioned medium from selected clones after 72 h in culture (Fig. 1), with results comparable with those obtained by using a commercially available NGF ELISA (data not shown). As indicated by the arrow, a band corresponding to unprocessed NGF precursor was present only in the cell lysates, whereas medium was found to be free of any unprocessed form, thus suggesting an efficient processing of the precursor molecule in this cell line. Some of the rhNGF-producing clones were thoroughly characterized both in terms of daily production referred to their respective duplication times and for tetracycline regulation of the pTRE promoter (A.M.C., unpublished data). Among all of the hNGF-HeLaTetOff transfectants, particularly high levels of rhNGF production were observed for the clone 73, which secreted ≈433 ± 36 ng/ml recombinant protein in a 3-day culture (25-cm2 flask), with a daily production of 104.2 ± 11.8 ng per 105 cells. No NGF was detected both in WT cells and Mock clones stably transfected with the empty vector (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Western blot analysis of rhNGF. Different clones of hNGF-HeLaTetOff cells (5 × 105 per 25-cm2 flask) were cultured for 72 h. Cell lysates (5 μg) and proteins in the medium (5 μl of a 1:10 dilution) were separated on 12% SDS/PAGE and blotted onto nitrocellulose membrane. We loaded 2.5S mNGF (5 and 10 ng) on the same gel as positive controls. rhNGF was detected by probing the membrane with anti-hNGF Ab (H-20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and quantified by densitometric analysis of the NGF bands (image, Scion). Bands of mature NGF and proNGF are indicated by arrows. The blot is representative of several different experiments with similar results.

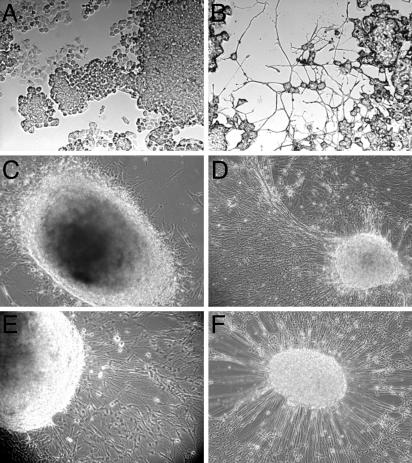

RhNGF Induces Differentiation and Survival of PC12 Cells and DRG. NGF treatment of PC12 cells, an in vitro model of sympathetic neurons, results in cell differentiation and survival (31). To examine whether the rhNGF was biologically active, PC12 cells were exposed to the conditioned medium from hNGF-producing clones or Mock cells. As shown in Fig. 2B, PC12 cells were greatly differentiated after 16-18 h of incubation with the rhNGF (5 ng/ml) produced by hNGF-HeLaTetOff (clone 73), whereas neurite outgrowth was absent in PC12 cells exposed to the culture medium of Mock cells (Fig. 2 A).

Fig. 2.

rhNGF induces differentiation of PC12 cells and DRG. (A) As a control, PC12 cells were incubated with equal volume of culture medium from Mock cells. (B) PC12 cells were exposed to rhNGF (5 ng/ml) produced by rhNGF-HeLaTetOff cells, and neurite outgrowth was evaluated after 16-18 h by phase-contrast microscopy. (C and D) As a control, ganglia were grown in the presence of equal volume of medium from Mock cells (C) or 2.5S mNGF (5 ng/ml) (D). (E and F) DRG from 8-day-old chick embryos cultured in the presence of rhNGF (5 ng/ml) produced by hNGF-HeLaTetOff cells (clone 73) for 48 and 96 h, respectively. Treatments were repeated every 3 days, and DRG differentiation and survival were monitored and recorded under a reversed microscope Olympus CX40 (×20) equipped with an Olympus camera.

The neurotrophic activity of the recombinant protein was also evaluated on DRG, which require NGF for differentiation and survival (12). DRG explants prepared from 8-day-old chicken embryos were cultured in the presence of conditioned medium from rhNGF-producing or Mock cells and monitored daily for neurite processes outgrowth. As shown in Fig. 2 E and F, DRG cultured in the presence of rhNGF (5 ng/ml) from hNGF-HeLaTetOff cells (clone 73) differentiated to an extent that was similar to that induced by 2.5S mNGF (5 ng/ml; Fig. 2D), whereas ganglia that were maintained in culture medium from Mock cells only showed high fibroblast proliferation due to the presence of serum (Fig. 2C). DRG differentiation occurred after 18-24 h of incubation of ganglia with murine and rhNGF and could be maintained for as long as 3 weeks, thus clearly indicating that our rhNGF was biologically active.

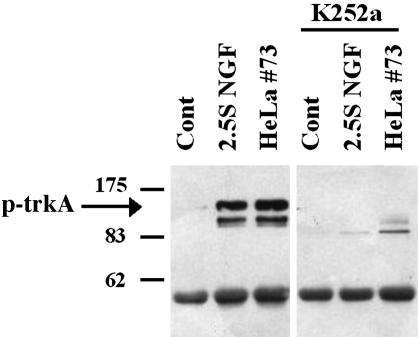

Activation of trkA Phosphorylation. NGF-induced survival and differentiation are known to be mediated by binding and activation of the high-affinity NGF-receptor trkA (32). To further assess the biological activity of the rhNGF, we analyzed its ability to induce phosphorylation of trkA in PC12 cells. Immunoprecipitation studies revealed that exposure of PC12 cells (clone 615) for 5 min to the culture medium of hNGF-HeLaTetOff cells (5 ng of rhNGF per ml) was able to induce trkA phosphorylation (p-trkA) comparable with 2.5S mNGF (5 ng/ml), whereas no induction was observed in PC12 cells incubated with the culture medium of Mock cells (Fig. 3). Quantitative estimation of the p-trkA bands indicated that trkA phosphorylation induced by rhNGF was 100% of that obtained with equal amounts of the 2.5S mNGF, and it was prevented by a 10-min preincubation with 100 nM K252a, the cell-permeable tyrosine kinase inhibitor (Fig. 3). These results suggest that the morphological changes induced by the rhNGF in both PC12 cells and DGR occur through binding of the protein to the high-affinity trkA receptor and activation of the correct signaling pathway.

Fig. 3.

rhNGF induces trkA phosphorylation in PC12 cells. PC12 cells (615) were exposed for 5 min to rhNGF (5 ng/ml) produced by hNGF-HeLaTetOff (clone 73), and 300 μg of total proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-pan-trk Ab (C-14, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Immunocomplexes were then separated on 7.5% SDS/PAGE, and p-trkA was detected by probing the membrane with the anti-p-Tyr mAb (PY99, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). As a control, cells were treated for 5 min with 2.5S NGF (5 ng/ml). Where indicated, inhibition of trkA was accomplished by incubating the cells for 10 min with K252a (100 nM, Calbiochem) before addition of rhNGF or 2.5S NGF. Arrow indicates the position of the p-trkA species.

Scale-Up Production of rhNGF in Minibioreactors. The main goal of this study was to set up a procedure for production of large amounts of rhNGF suitable for in vivo tests on animal models and, in prospective, for therapeutic purposes. However, even in a 3-day flask culture (175-cm2 flasks) the daily (≈5 μg per 35 ml) and total (≈15 μg per 35 ml) levels of recombinant protein produced were quite low, meaning that production of a reasonable amount of rhNGF and its purification process would require the manipulation of large volumes of medium.

To bypass this problem we set up a high-density cell-culture system by using the miniPERM bioreactors, as described in Materials and Methods. For continued production of rhNGF, hNGF-HeLaTetOff cells (clone 73) were seeded on the membranes of the production module and the medium was harvested every 24-48 h and replaced with fresh medium. Cell cultures in the miniPERMs were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS, because this serum concentration was found to affect rhNGF production slightly compared with 10% serum (A.M.C., unpublished data). Fig. 4A represents an example of the production profile of one miniPERM in culture for 20 days. Western blot analysis of collected media showed that the amount of rhNGF that was released in the culture medium ranged from 12.8 to 40.3 μg/ml recombinant protein at each harvest, corresponding to a daily rate of rhNGF production of 224-715 μg per 35 ml. Similar profiles and secretion levels were obtained by using the NGF ELISA kit (data not shown). The time-course experiment shown in Fig. 4B shows that this miniPERM allowed to obtain 7.8 mg of rhNGF (15.9 μg/ml) in ≈16 days. Production profiles were slightly different among the miniPERMs that we used; however, our data indicated a daily yield of rhNGF of 224-1,550 μg of protein, thus leading to a total amount of 7.8-10.36 mg of recombinant protein in ≈2 weeks, with an average concentration of 20.3 ± 3 μg/ml.

Fig. 4.

Levels of rhNGF produced by hNGF-HeLaTetOff cells in the miniPERM. hNGF-HeLaTetOff cells (clone 73) were cultured in 35 ml of DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS, and conditioned medium was harvested every 24-48 h. Levels of rhNGF in the medium (5 μl of 1:10 dilutions) were analyzed by Western blot, followed by densitometric analysis of the bands as described in Materials and Methods. (A) The production profile (μg/ml released daily) of one miniPERM. (B) Time-course of total rhNGF (mg) production in the same miniPerm system in culture for 20 days.

Thus, our data indicate that this system allowed us to obtain total amounts of rhNGF that were ≈100-fold higher than in conventional flask-cultures and in reduced volumes of culture media, a feature that was relevant for the purification process. Moreover, culturing cells in 5% serum was also an optimal asset for obtaining a final product with less serum contaminants (A.M.C., unpublished data) and, therefore, more suitable for the in vivo studies. The purity and identity of the final product were analyzed by stained SDS/PAGE and Western blot analysis using an Ab against the N terminus of the mature form of human NGF (A.M.C., unpublished data). The purification and lyophilization manipulations apparently did not compromise the biological activity of the rhNGF (data not shown), and the ED50 was determined to be ≈2.5 ng/ml.

rhNGF Exerts Neurotrophic Activity in Newborn Mice. To characterize the in vivo activity of our rhNGF, we investigated its effect on NGF target cells and NGF mediators known to be regulated by this neurotrophin, and compared this effect with the purified mouse 2.5S NGF routinely prepared in our laboratory according to the method of Bocchini and Angeletti (33).

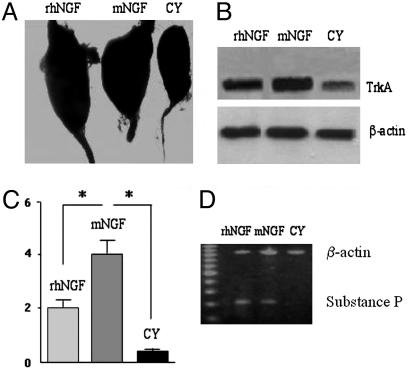

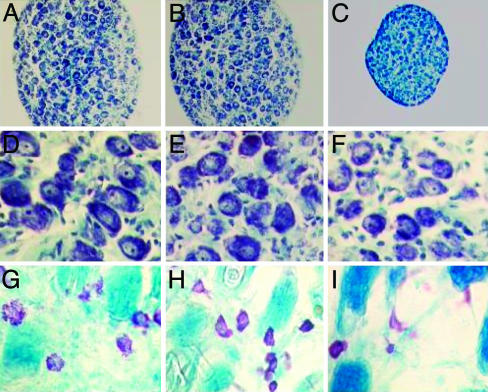

We first found that rhNGF administration for 5 consecutive days at the doses indicated in Materials and Methods caused no evident undesired effects on body weight, suckling behavior, or early postnatal somatic markers, such as eyelid opening and tooth eruption. As shown in Fig. 5A, we found that treatment with rhNGF induced hypertrophy of the SCG compared with the ganglia of mice treated with CY, and the effect was comparable with that given by the mNGF. Histological analysis of the ganglia (Fig. 6 A-F) also indicated that our rhNGF induced hypertrophy of the sympathetic neurons (Figs. 6 A and D, respectively at low and high magnification), as compared with the ganglia from CY-treated mice (Figs. 6 C and F). As shown, the effect of the rhNGF was similar to that induced by the mNGF (Figs. 6 B and E).

Fig. 5.

Effect of rhNGF in neonatal mice. (A) Macroscopic hypertrophy of SCG of mice treated for 5 days with rhNGF or mNGF vs. control mice (CY). Toluidine blue-stained ganglia were observed at magnification ×15. (B) Example of Western blot analysis of trkA levels in skin tissues after injection of rhNGF, mNGF, or CY. Total proteins (30 μg) were separated on 12.5% SDS/PAGE, transferred to PVDP, and probed with anti-trkA Ab (763, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The β-actin band was used as internal control. (C) RT-PCR ELISA of SP mRNA content in the skin of mice treated with rhNGF or mNGF. Data are expressed as mean levels ± SD. *, P < 0.05 vs. control (CY). (D) Example of ethidium bromide-stained gel for SP mRNA levels and using β-actin as normalizing factor.

Fig. 6.

Histological analysis of SCG and skin tissues. Mice were treated with rhNGF or mNGF, and ganglia were dissected, fixed, and stained with toluidine blue. (A-C) Photographs showing the hypertrophy of SCG induced by rhNGF (A) and mNGF (B) compared with ganglia from CY-treated mice (C) at low magnification (×180). (D-F) Sections of the SCG (at higher magnification, ×450) from mice treated with rhNGF (D) and mNGF (E) vs. CY-treated (F) mice. (G-I) Histological sections of toluidine blue-stained cutaneous tissues showing the distribution and degranulation of mast cells in proximity of the injection site of rhNGF-treated (G), mNGF-treated (H), and CY-treated (I) mice. (Magnification, ×540.)

Because NGF is known to up-regulate its receptor (34), we next investigated the effect of rhNGF and mNGF administration on trkA expression in the ganglia, as well in the cutaneous tissues in proximity of the areas where NGF was injected. As expected, immunoblotting analyses revealed that our rhNGF induced up-regulation of trkA both in the SCG (data not shown) and in the mice skin tissues, where a 2-fold induction of trkA expression was elicited by both rhNGF and mNGF (Fig. 5B).

Mast cells are immune-related cells that are receptive to NGF and SP (35, 36). To further characterize the in vivo effect of rhNGF on NGF-target cells, cutaneous tissues were also examined for the distribution and degranulation of mast cells. As shown in Fig. 6 G-I, our data indicate that rhNGF administration elicited an increase in the number of mast cells (Fig. 6G) and diffuse degranulation, compared with cytochrome-treated mice (Fig. 6I), and the effect was similar to that induced by mNGF (Fig. 6H).

NGF is also known to stimulate synthesis and release of SP, a neuropeptide involved in sensory peripheral response and in neuroimmune regulation (37). To further explore the activity of our rhNGF, cutaneous tissues of mice treated with rhNGF were also analyzed for the levels of this neuropeptide. As shown in Fig. 5C, semiquantitative analysis of SP mRNA content by RT-PCR ELISA revealed that both rhNGF and mNGF administration were able to enhance SP gene expression by ≈2- and 4-fold, respectively, compared with the treatment with CY. This induction was also evident by ethidium bromide staining of RT-PCR products (Fig. 5D).

Finally, to assess the immunological activity of our rhNGF and evaluate the possibility to quantify our rhNGF with a commercially available ELISA kit, we tested the concentration of recognizable rhNGF, before injection and in the cutaneous tissues after injection. The results showed that our rhNGF can be quantified as free molecule before injection and soon after injection in NGF-responsive cells (data not shown).

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to describe a method to obtain large amount of rhNGF and demonstrate its biological activity. The investigation showed that our rhNGF possesses a biological activity similar to that of the purified 2.5S mNGF both in vitro and in vivo, and it suggests the possibility of using this rhNGF in preclinical studies to evaluate its therapeutic potential.

The development of an effective procedure for producing high levels of rhNGF is fundamental to providing amounts of rhNGF that are suitable for further clinical trials and, eventually, pharmacological applications. mNGF has been successfully used in many pathological conditions (1, 3-7), but, despite its beneficial effects, it cannot be used for human therapy on a large scale. Nevertheless, production of correctly folded rhNGF in heterologous systems is a major challenge. For example, the consistent positive effect in a number of animal models of peripheral neuropathies (36, 38) contrasts with the poor activity obtained with the rhNGF on human diabetic neuropathies (27). These contradictory results suggest the existence of differences in biological activities between the rhNGF preparations and their native counterpart. This hypothesis seems to be consistent with our findings (L. Aloe, unpublished data).

In this work, we provide evidence for production on a laboratory scale of large amounts of a rhNGF that was shown to possess full biological activity both in vitro and, mostly important, in vivo studies. Production of the recombinant human protein was obtained by means of conventional recombinant DNA technologies, and, interestingly, the host cell line was found to be an efficient system for processing the proNGF as the culture medium of hNGF-HeLaTetOff clones was found to be devoid of any unprocessed form of NGF. This finding is of utmost importance in regard of its possible therapeutic use as, according to recent data, preferential binding of the proNGF form to the p75 receptor opposes the neurotrophic activity of the mature NGF (39). In addition, the hNGF-HeLaTetOff clone 73 was characterized also in terms of promoter responsiveness to different serum concentration. These results were important for the establishment of the most suitable culture conditions for the scale up process. In fact, for large scale culture of mammalian cells the cost of serum could be a serious burden. The possibility of obtaining large amount of recombinant protein in 5% serum not only reduced the costs of production but also improved the purification process by decreasing the presence of serum contaminants.

Scale-up production of rhNGF was obtained by using miniPERM bioreactors for high-density culture of mammalian cells. This system allowed us to obtain amounts of recombinant protein ≈100-fold higher than in conventional flask cultures, thus representing an optimal asset for laboratory-scale production of rhNGF in reduced volumes of medium and greatly simplifying the first steps of the purification procedure.

Finally, we demonstrate that our rhNGF is biologically active because it was able to induce differentiation of DRG and PC12 cells, as well as elicit trkA phosphorylation to an extent comparable with that induced by equal amounts of the 2.5S mNGF. Most importantly, here we present data demonstrating its marked biochemical, morphological, and pharmacological effects in vivo. First, this rhNGF was found to exert neurotrophic activity on SCG in newborn mice, as demonstrated by the histological analyses showing its hypertrophic effect both on the ganglia in toto and, in particular, on the sympathetic neurons. Our data show that the neurotrophic activity of the rhNGF was identical to that of the mNGF. These results also were confirmed by data regarding the activity of the recombinant protein on the cutaneous tissues, in which (in accordance with refs. 34-37) we observed increased number and degranulation of mast cells, as well as up-regulation of trkA protein and SP mRNA levels. Also, note that our rhNGF did not cause any apparent hyperalgesia, although injection-site pain has been associated frequently with NGF administration (11, 40).

Our data, by providing evidence for structural and pharmacological effects of the rhNGF comparable with the mNGF, pose confidence regarding the possibility of therapeutic application of NGF. It would be interesting to test this rhNGF also in an animal model of neurodegeneration.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Associazione Levi-Montalcini. L. Aloe and L.L. were supported by the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Bologna.

Author contributions: A.M.C., L. Alberghina, E.M., L. Aloe, and R.L.-M. designed research; A.M.C., N.F., M.C., and L.L. performed research; A.M.C., N.F., E.M., L. Aloe, and L.L. analyzed data; and A.M.C., L. Alberghina, E.M., and L. Aloe wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest statement: A PCT patent application covering the research reported in this work was filed on September 23, 2005 by Associazione Levi-Montalcini and the University of Milano-Bicocca (Inventors: L. Alberghina, E.M., and A.M.C.).

Abbreviations: NGF, nerve growth factor; rhNGF, recombinant human NGF; mNGF, murine NGF; DRG, dorsal root ganglia; CY, cytochrome c; SCG, superior cervical ganglion; SP, substance P.

References

- 1.Aloe, L. & Calzà, L., eds. (2004) Progress in Brain Research (Elsevier, Amsterdam), Vol. 146.

- 2.Levi-Montalcini, R. (1987) Science 237, 1154-1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lambiase, A., Rama, P., Bonini, S., Caprifoglio, G. & Aloe, L. (1998) N. Engl. J. Med. 338, 1174-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernabei, R., Landi, F., Bonini, S., Onder, G., Lambiase, A., Pola, R. & Aloe, L. (1999) Lancet 354, 307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Landi, F., Aloe, L., Russo, A., Cesari, M., Onder, G., Bonini, S., Carbonin, P. U. & Bernabei, R. (2003) Ann. Intern. Med. 139, 635-641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tuveri, M., Generini, S., Matucci-Cernic, M. & Aloe, L. (2000) Lancet 356, 1739-1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiaretti, A., Piastra, M., Caresta, E., Nanni, L. & Aloe, L. (2002) Arch. Dis. Child. 87, 446-448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Villoslada, P., Hauser, S. L., Bartke, I., Unger, J., Heald, N., Rosenberg, D., Cheung, S. W., Mobley, W. C., Fisher, S. & Genain, C. P. (2000) J. Exp. Med. 191, 1799-1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuszynski, M. H. (2002) Lancet Neurol. 1, 51-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Rosa, R., Garcia, A. A., Braschi, C., Capsoni, S., Maffei, L., Berardi, N. & Cattaneo, A. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 3811-3816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McArthur, J. C., Yiannoutsos, C., Simpson, D. M., Adornato, B. T., Singer, E. J., Hollander, H., Marra, C., Rubin, M., Cohen, B. A., Tucker, T., et al. (2000) Neurology 54, 1080-1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levi-Montalcini, R. (1952) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 55, 330-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuen, E. C., Howe, C. L., Li, Y., Holtzman, D. M. & Mobley, W. C. (1996) Brain Dev. 18, 362-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bracci-Laudiero, L., Celestino, D., Starace, G., Antonelli, A., Lambiase, A., Procoli, A., Rumi, C., Lai, M., Picardi, A., Ballatore, G., et al. (2003) J. Neuroimmunol. 136, 130-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faradji, V. & Sotelo, J. (1990) Acta Neurol. Scand. 81, 402-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonini, S., Lambiase, A., Bonini, S., Angelucci, F., Magrini, L., Manni, L. & Aloe, L. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 10955-10960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ullrich, A., Gray, A., Berman, C. & Dull, T. J. (1983) Nature 303, 821-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edwards, R. H., Selby, M. J., Garcia, P. D. & Rutter W. J. (1988) J. Biol. Chem. 263, 6810-6815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shooter, E. M. (2001) Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 601-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanaya, E., Higashizaki, T., Ozawa, F., Hirai, K., Nishizawa, M., Tokunaga, M., Tsukui, H., Hatanaka, H. & Hishinuma, F. (1989) Gene 83, 65-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishizawa, M., Ozawa, F., Higashizaki, T., Hirai, K. & Hishinuma, F. (1993) Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 38, 624-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Negro, A., Martini, I., Bigon, E., Cazzola, F., Minozzi, C., Skaper, S. D. & Callegaro, L. (1992) Gene 110, 251-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rattenholl, A., Lilie, H., Grossmann, A., Stern, A., Schwarz, E. & Rudolph R. (2001) Eur. J. Biochem. 268, 3296-3303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barnett, J., Chow, J., Nguyen, B., Eggers, D., Osen, E., Jarnagin, K., Saldou, N., Straub, K., Gu, L., Erdos, L., et al. (1991) J. Neurochem. 57, 1052-1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen, S. J., Robertson, A. G., Tyler, S. J., Wilcock, G. K. & Dawbarn, D. (2001) J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 47, 239-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iwane, M., Kitamura, Y., Kaisho, Y., Yoshimura, K., Shintani, A., Sasada, R., Nakagawa, S., Kawahara, K., Nakahama, K. & Kakinuma, A. (1990) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 171, 116-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Apfel, S. C. (2002) Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 50, 393-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hempstead, B. L., Rabin, S. J., Kaplan, L., Reid, S., Parada, L. F. & Kaplan, D. R. (1992) Neuron 9, 883-896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colangelo, A. M., Fink, D. W., Rabin, S. J. & Mocchetti, I. (1994) Glia 12, 117-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tirassa, P., Manni, L., Stenfors, C., Lundeberg, T. & Aloe, L. (2000) J. Biotechnol. 84, 259-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greene, L. A. & Tischler, A. S. (1976) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 73, 2424-2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaplan, D. R., Martin-Zanca, D. & Parada, L. F. (1991) Nature 350, 158-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bocchini, V. & Angeletti, P. U. (1969) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 64, 787-794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holtzman, D. M., Li, Y., Parada, L. F., Kinsman, S., Chen, C. K., Valletta, J. S., Zhou, J., Long, J. B. & Mobley, W. C. (1992) Neuron 9, 465-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aloe, L. & Levi-Montalcini, R. (1977) Brain Res. 133, 358-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brewster, W. J., Fernyhough, P., Diemel, L. T., Mohiuddin, L. & Tomlinson, D. R. (1994) Trends Neurosci. 17, 321-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levi-Montalcini, R., Aloe, L. & Alleva, E. (1990) Prog. NeuroEndocrinImmunol. 3, 1-10. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Apfel, S. C., Lipton, R. B., Arezzo, J. C. & Kessler, J. A. (1991) Ann. Neurol. 29, 87-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harrington, A. W., Leiner, B., Blechschmitt, C., Arevalo, J. C., Lee, R., Mörl, K., Meyer, M., Hempstead, B. L., Yoon, S. O. & Giehl, K. M. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 6226-6230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shu, X.-Q. & Mendell, L. M. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 7693-7696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]