Abstract

The interaction of chondrocytes with the extracellular-matrix environment is mediated mainly by integrins. Ligated integrins are recruited to focal adhesions (FAs) together with scaffolding proteins and kinases, such as integrin-linked kinase (Ilk). Ilk binds the cytoplasmic domain of β1-, β2- and β3-integrins and recruits adaptors and kinases, and is thought to stimulate downstream signalling events through phosphorylation of protein kinase B/Akt (Pkb/Akt) and glycogen synthase kinase 3-β (GSK3-β). Here, we show that mice with a chondrocyte-specific disruption of the gene encoding Ilk develop chondrodysplasia, and die at birth due to respiratory distress. The chondrodysplasia was characterized by abnormal chondrocyte shape and decreased chondrocyte proliferation. In addition, Ilk-deficient chondrocytes showed adhesion defects, failed to spread and formed fewer FAs and actin stress fibres. Surprisingly, phosphorylation of Pkb/Akt and GSK3-β is unaffected in Ilk-deficient chondrocytes. These findings suggest that Ilk regulates actin reorganization in chondrocytes and modulates chondrocyte growth independently of phosphorylation of Pkb/Akt and GSK3-β.

Introduction

The longitudinal growth of bones is carried out by a specialized cartilage structure called the growth plate, in which chondrocytes undergo a sequential differentiation process that is characterized by proliferation, growth arrest, maturation and hypertrophy, leading to mineralization of the matrix, which is finally replaced by bone.

Chondrocytes are surrounded by a network of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, and lack cell–cell contacts. Their interaction with ECM proteins is essential for their survival, proliferation and differentiation (Svoboda,1998). Integrins are a major class of cell adhesion molecules and are expressed on all cells, including chondrocytes, and mediate adhesion to the ECM (Hynes, 2002). Integrins are α/β-heterodimers that associate with intracellular proteins on ligand binding. An important binding partner of β1-, β2- and β3-integrin cytoplasmic domains is integrin-linked kinase (Ilk; Wu & Dedhar, 2001). Ilk is a multidomain protein composed of four amino-terminal ankyrin (ANK) repeats, a pleckstrin-homology-like domain and a carboxy-terminal serine/threonine kinase domain (Hannigan et al., 1996). The first ANK repeat binds the LIM-only protein Pinch (particularly interesting new cysteine histidine-rich protein; Tu et al., 1999). As well as interacting with integrins, the kinase domain can interact with paxillin (Nikolopoulos & Turner, 2001) and α- and β-parvin, which are members of a newly identified family of actin-binding proteins (Nikolopoulos & Turner, 2000; Olski et al., 2001; Tu et al., 2001; Yamaji et al., 2001).

Overexpression of Ilk disrupts the architecture of epithelial cells, reduces integrin-mediated cell adhesion and stimulates pericellular fibronectin-matrix assembly, adhesion-independent cell proliferation and cell survival (Wu & Dedhar, 2001). Several Ilk functions are thought to be mediated through the phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase 3-β (GSK3-β) and protein kinase B/Akt (Pkb/Akt). Phosphorylation of GSK3-β by Ilk, or by the Wnt signalling pathway, inhibits its activity (Delcommenne et al., 1998), which results in the upregulation of cyclin D1 expression (Wu & Dedhar, 2001). Pkb/Akt is a serine/threonine kinase, which regulates cell-cycle progression, cell survival and insulin signalling. Activation of Pkb/Akt requires its phosphorylation at residues Thr308 and Ser473. Thr308 is phosphorylated by 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (Pdk1; Alessi et al., 1997). Ser473 is also phosphorylated in a phosphatidyinositol-3-kinase-dependent manner, but the identity of the kinase, known as Pdk2, is unclear. Studies by Dedhar and co-workers suggested that Ilk directly phosphorylates Pkb/Akt at Ser473 and is, therefore, Pdk2 (Persad et al., 2001). However, two independent reports from other laboratories have shown that Ilk is involved in phosphorylation of Pkb/Akt by an indirect rather than a direct mechanism (Lynch et al., 1999; Hill et al., 2002).

Loss of Ilk expression in mice leads to peri-implantation lethality (Sakai et al., 2003). To test directly the function of Ilk in chondrocytes, we used the Cre–LoxP system to generate mice that lack the Ilk gene in chondrocytes only. We show here that these mice develop chondrodysplasia, caused by impaired chondrocyte proliferation. Surprisingly, Ilk-deficient chondrocytes show normal phosphorylation of Pkb/Akt and GSK3-β.

Results

High levels of Ilk expression in cartilage

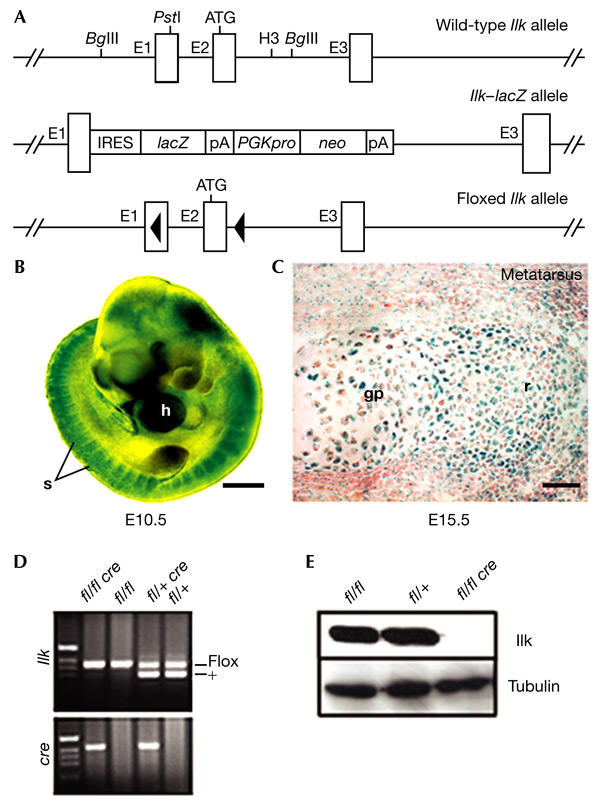

To determine the expression pattern of Ilk during development, IlklacZ/+ mice were produced (Fig. 1A; Sakai et al., 2003). Staining of whole-mount embryos for LacZ expression at E10.5 showed strong expression in the somites and in the heart, and lower levels of expression in other tissues (Fig. 1B). At E12.5, LacZ expression was ubiquitous, with high levels in the brain, the cartilaginous anlage of long bones, the vertebral bodies, the ribs and the pre-chondrogenic mesoderm of the digits (data not shown). At E15.5, LacZ expression levels were high in chondrocytes from the epiphyseal cartilage and growth plates (Fig. 1C). This high level of LacZ activity was maintained in chondrocytes from adult cartilages (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Integrin-linked kinase expression during chondrocyte differentiation, and generation of mice that lack integrin-linked kinase in cartilage. (A) Partial map of the wild-type, integrin-linked kinase (Ilk)–lacZ and LoxP-flanked Ilk alleles. (B) X-gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-galactoside) staining of a whole-mount E10.5 embryo heterozygous for the IlklacZ allele. Scale bar, 500 μm. (C) LacZ expression in E15.5 cartilage. High levels of LacZ expression are detected in resting (r) and growth plate (gp) chondrocytes from metatarsal cartilage. Scale bar, 50 μm. (D) PCR genotyping of Col2a1–Cre/Ilk mice. (E) Western blot analysis of Ilk expression in primary chondrocytes isolated from newborn limb-epiphyseal and growth-plate cartilage. E1–3, exons 1–3; fl, floxed Ilk allele; h, heart; H3, HindIII; IRES, internal ribosomal entry site; pA, polyadenylation signal; PGKpro, phosphoglycerate kinase promoter; neo, neomycin resistance gene; s, somite.

Chondrocyte-specific deletion of the Ilk gene

Ilk null (IlklacZ/lacZ) mice die shortly after implantation (Sakai et al., 2003). We therefore generated a mouse strain carrying a LoxP-flanked (floxed) Ilk gene (Ilkflox/flox; Fig. 1A). To delete the Ilk gene in chondrocytes, we crossed Ilkflox/flox mice with mice expressing the Cre recombinase under the control of the mouse collagen II (Col2a1) promotor (Sakai et al., 2001) to obtain mice with the genotype Col2a1–cre+/Ilkflox/flox (called Col2–Ilk; Fig. 1D).

To test the efficiency of the Cre recombinase in vivo, we isolated chondrocytes from the cartilage of long bones of control and mutant newborn mice, and determined Ilk levels by western blotting. All Col2–Ilk mice tested showed a complete absence of Ilk expression in chondrocytes (Fig. 1E). This is in agreement with earlier results that showed Col2a1–cre activity in condensing mesenchyme and cartilage (Sakai et al., 2001).

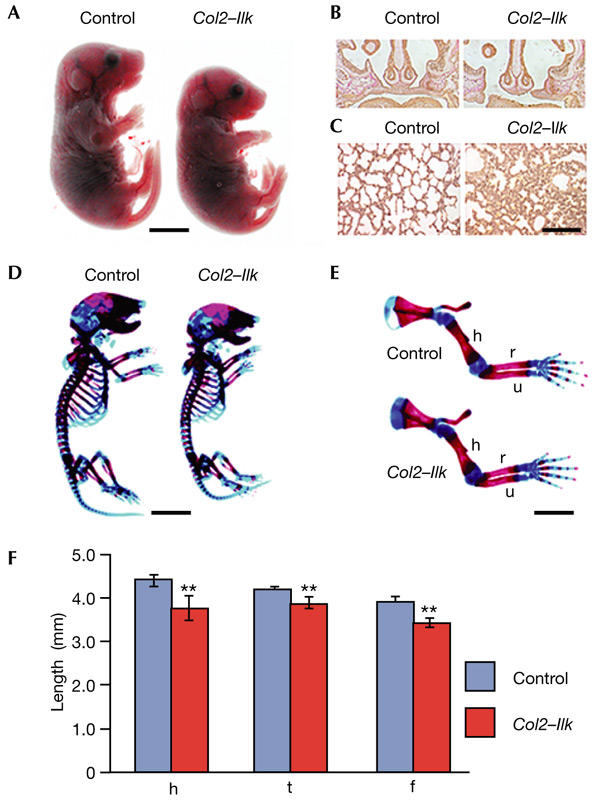

Col2–Ilk mice show perinatal lethality and dwarfism

Until E16.5, the external appearance of Col2–Ilk embryos was indistinguishable from that of controls. At E17.5 and the newborn stage they were 5% shorter than controls (Fig. 2A). Around 70% of the Col2–Ilk mice had a cleft palate (Fig. 2B) and died 1–2 h after birth. The remaining Col2–Ilk mice suffered from lung hypoplasia (Fig. 2C) and died due to breathing difficulties 10–24 h after birth.

Figure 2.

Morphology of Col2–Ilk mice. (A) Col2–Ilk mice are smaller than control mice at birth. (B) The majority of mutant mice develop a cleft palate. (C) Lung hypoplasia in Col2–Ilk mice. (D) Whole-mount staining with alcian blue and alizarin red shows that a newborn mutant has a smaller skeleton than a control mouse. (E) Long bones of mutant forelimbs are reduced in length. (F) Length of humerus (h), femur (f) and tibia (t) of control and Col2–Ilk newborn mice (asterisks indicates p < 0.01 versus control, n = 4). Scale bars, 4 mm in (A) and (D), 100 μm in (B), 50 μm in (C) and 2 mm in (E). h, humerus; r, radius; u, ulna.

Whole-mount skeletal staining of newborn mice showed that all bones of the axial, appendicular and craniofacial skeleton formed in Col2–Ilk mice, but were smaller than in controls. In addition, the thorax was small and narrow (Fig. 2D), suggesting that the lung phenotype was caused by reduced ribcage size. The growth of forelimbs and hindlimbs was retarded by 10–15% (Fig. 2E,F).

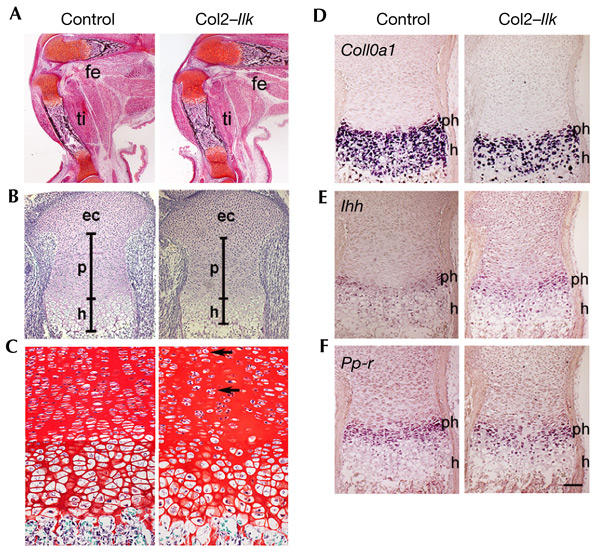

Col2–Ilk bones have short growth plates

The Col2a1–cre transgene is active in the condensing mesenchyme of digits and somites (Sakai et al., 2001), where Ilk is highly expressed (Fig. 1B; and data not shown). However, histological analysis of Col2–Ilk mice at E13.5–E14.5 showed that the cartilaginous anlage of all endochondral bones were normal (data not shown), indicating that Ilk is not required either for sclerotomal cell migration to the notochord or for mesenchymal condensation.

We then analysed bone morphology. At E17.5, long bones from Col2–Ilk mice were of normal shape, contained periosteal as well as trabecular bones (Fig. 3A) and had normal epiphyseal cartilage. However, the growth plates were significantly shortened (Fig. 3B). The proliferative zone was less affected than the hypertrophic zone, which was reduced by 30% (Fig. 3B). At the newborn stage, the reduction in size of the growth plates became more pronounced. In addition, the columnar arrangement of chondrocytes was disorganized (Fig. 3C) and the usually flattened proliferative chondrocytes were round (Fig. 3C). Electron microscopy confirmed these observations, and showed a normal fibrillar collagen network in Col2–Ilk cartilage (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Analysis of the skeletal defect of Col2–Ilk mice. (A) Safranin orange/van Kossa-stained sections of the knee region show normal apperance and mineralization of mutant tibia (ti) and femur (fe) at E17.5. (B) Haematoxilin/eosin stained sections through the growth plate. The epiphyseal cartilage (ec) was defined as extending from the joint surface to the transition to the proliferating zone (p), where cells start to become arranged in stacks and become flattened. The transition between the proliferating cell stacks and the cells that showed an increase in cell volume was defined as being the beginning of the hypertrophic zone. Note that the epiphyseal cartilage is normal, but the length of the proliferative and hypertrophic zones are reduced in the Col2–Ilk growth plate. (C) Sections of newborn growth plate from the proximal humerus, stained with Safranin orange. Note the slight disorganization of the columns, and the more rounded chondrocyte shape (arrows) in the proliferative zone of the mutant. (D–F) In situ hybridization analysis of tibial sections from newborn animals using antisense complementary RNA probes for collagen X (Col10a1), Indian hedgehog (Ihh) and parathroid hormone/parathroid-hormone-related-peptide receptor (Ppr) mRNAs. h, hypertrophic zone; ph, pre-hypertrophic zone. Scale bars, 250 μm in (A), 100 μm in (B), 25 μm in (C) and 75 μm in (D–F).

Ilk is not required for chondrocyte maturation

We then analysed cartilage differentiation. Collagen type X (Col10a1) mRNA, a marker for pre-hypertrophic and hypertrophic chondrocytes, was expressed at normal levels in Col2–Ilk growth plates. However, in agreement with the histological data, the hypertrophic zone was reduced (Fig. 3D). Expression of Indian hedgehog (Ihh) and parathyroid hormone/parathyroid-hormone-related-peptide receptor (Ppr) mRNA was seen in the pre-hypertophic zones, and was not altered in mutant mice (Fig. 3E,F). Immunohistochemistry showed normal collagen type II, collagen type X and aggrecan expression in Col2–Ilk cartilage (data not shown).

Finally, we carried out histochemical staining for alkaline phosphatase (a marker for osteoblasts) and tartrate-resistant acid-phosphatase (a marker for osteoclasts). We found no difference between wild-type and Col2–Ilk tissues (data not shown).

Together, these data suggest that chondrocyte and osteoblast–osteoclast differentiation are not impaired in Col2–Ilk mice, and that the reduction of growth-plate height might be caused by abnormal chondrocyte proliferation and/or apoptosis.

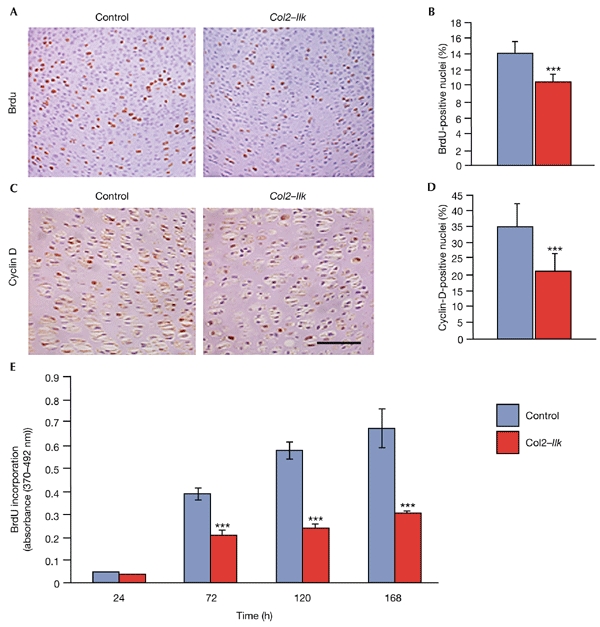

Ilk controls the G1–S transition of the chondrocyte cell cycle

Endochondral bone formation depends on chondrocyte proliferation, hypertrophy and subsequent apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes. A BrdU (5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine) incorporation assay, which specifically labels proliferating cells in the synthesis (S) phase of the cell cycle, showed a 29% reduction in BrdU-positive chondrocytes in Col2–Ilk growth plates in vivo (Fig. 4A,B). The D-type cyclins have a crucial function in controlling G1 progression and entry into S phase. To test whether the reduced number of BrdU-positive cells is due to diminished cyclin expression, we immuno stained bone sections with an antibody that detects all cyclin-D isoforms (D1, D2 and D3). As shown in Fig. 4C,D, the number of cyclin-D-positive nuclei was reduced by 40% in Col2–Ilk growth plates, suggesting that Ilk controls G1–S transition by regulating cyclin-D expression. Finally, serumstarved Col2–Ilk primary chondrocytes showed a reduced rate of BrdU incorporation after stimulation with 10% serum in culture (Fig. 4E), providing further evidence for a defect in G1–S transition.

Figure 4.

Reduced proliferation of integrin-linked-kinase-deficient chondrocytes. (A) BrdU (5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine) labelling of tibiae of control and Col2–Ilk newborn mice. (B) Quantification of BrdU incorporation. Data are expressed as the mean ± s.d. (*** indicates P < 0.001). (C) Cyclin-D immunostaining of humerus tissue from newborn mice. (D) Quantification of cyclin-D-stained nuclei (*** indicates P < 0.001). (E) Proliferation of Col2–Ilk and control primary chondrocytes in vitro. Scale bar, 25 μm in (A,C).

A few apoptotic cells, as determined by a TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotidyl-transferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labelling) assay, were found in the periosteum and the chondro-osseous junction of control and Col2–Ilk cartilage. However, the number was not increased in Col2–Ilk cartilage (data not shown).

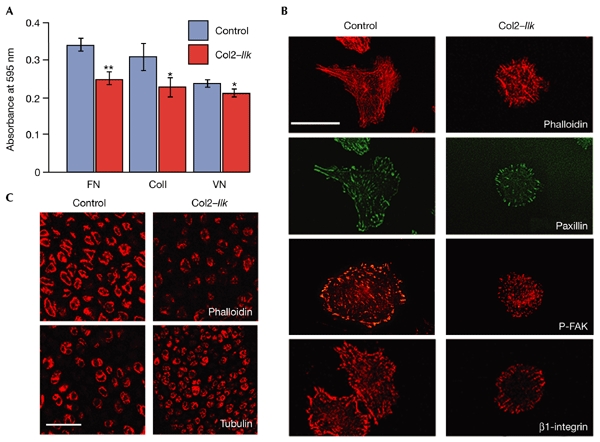

Ilk modulates adhesion and spreading of chondrocytes

Ilk binds the cytoplasmic domain of β1- and β3-integrins, which are highly expressed in chondrocytes. Fluorescence-activated cell-sorting analysis showed that the expression levels of β1- and β3-integrins are not changed in mutant cells (data not shown). The adhesion of Col2–Ilk chondrocytes to fibronectin and collagen I was reduced by 30% and 32%, respectively, from that of controls (Fig. 5A); adhesion to vitronectin was reduced only slightly (Fig. 5A). Control cells spread on fibronectin and formed robust stress fibres and numerous focal-adhesion sites throughout the cell surface. These sites contained β1-integrin, paxillin, focal-adhesion kinase (FAK), phosphorylated FAK and vinculin (Fig. 5B; and data not shown). By contrast, Col2–Ilk chondrocytes spread less, had shorter and more irregular F-actin fibres and formed fewer focal contacts, which were concentrated at the cell periphery (Fig. 5B). The tubulin and vimentin network was normal (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Adhesion and spreading defects of integrin-linked-kinase-deficient chondrocytes. (A) Reduced adhesion of mutant chondrocytes to fibronectin (FN), collagen I (ColI) and vitronectin (VN). * indicates P < 0.05; ** indicates P < 0.01. (B) Immunostaining of control and Col2–Ilk chondrocytes seeded on fibronectin for paxillin, phosphorylated focal-adhesion kinase (P-FAK), β1-integrin and F-actin (phalloidin staining). Note the rounded appearance of the mutant chondrocytes, which have fewer, shorter actin fibres and a reduced number of focal contacts. (C) Confocal microscopic analysis of F-actin (stained for phalloidin) and the microtubular network (stained for α-tubulin) in tibial sections. Note the irregular, punctate actin distribution in mutant mice. No obvious difference from the wild type was seen in the organization of the microtubular network in sections from mutants. Scale bars, 20 μm in (B) and 40 μm in (C).

Next, we analysed F-actin distribution in tissue sections. Whereas control chondrocytes had a continuous F-actin ring beneath the cell membrane, Col2–Ilk chondrocytes showed a punctate distribution of F-actin beneath the plasma membrane (Fig. 5C). Similar to cultured cells, the distribution of tubulin and vimentin was not affected in Col2–Ilk tissue (Fig. 5C; and data shown).

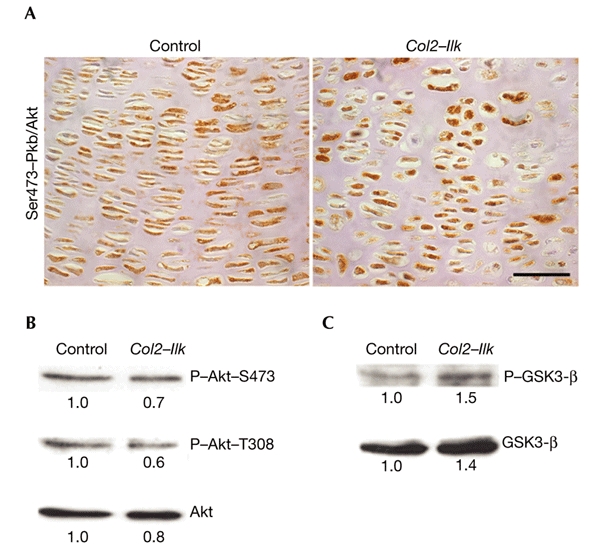

Normal phosphorylation of Pkb/Akt and GSK3-β in vivo

Ilk is thought to phosphorylate Pkb/Akt (on Ser473) and GSK3-β on (Ser9), which in turn modulate cell-cycle progression and cell survival. To test whether phosphorylation of Pkb/Akt is altered in Col2–Ilk mice, we immunostained sections of growth plates from newborn mice with an antibody that reacts specifically with phosphorylated serine residues at position 473 in Pkb/Akt. Surprisingly, the immunoreactivity was the same in control and Col2–Ilk growth-plate cells (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

Lack of integrin-linked kinase has no effect on the phosphorylation of protein kinase B/Akt and glycogen synthase kinase 3-β in chondrocytes. (A) Immunostaining of growth plates from newborn mice with an antibody against the phosphorylated Ser473 residue of protein kinase B/Akt (Pkb/Akt). No significant difference was seen between the number of positive chondrocytes in control and Col2–Ilk mice. (B,C) Total-cell lysates of primary chondrocytes from control and Col2–Ilk newborn mice were analysed by western blot analysis using antibodies against phospho-Pkb/Akt residues (P-Akt-T308 and P-Akt-S473) and phosphorylated glycogen synthase kinase 3-β (P-GSK3-β). The corresponding blots were re-probed with anti-Pkb/Akt and anti-GSK3-β. Scale bar in (A), 25 μm.

To confirm the immunostaining, we made cell extracts of primary chondrocytes, and analysed them by western blotting using antibodies that recognize the phosphorylated forms of the Pkb/Akt and GSK3-β kinases. In agreement with the immunostaining, Col2–Ilk chondrocytes showed normal phosphorylation of Pkb/Akt Ser473 and GSK3-β Ser9 (Fig. 6B,C).

Discussion

Chondrocyte-specific deletion of the Ilk gene affects the shape and proliferation of chondrocytes, leading to dwarfism. Differentiation and survival of Ilk-null chondrocytes, however, is unaffected.

The round shape of Ilk-null chondrocytes was associated with abnormal F-actin distribution in vivo and in vitro. They failed to spread, formed short actin stress fibres and accumulated F-actin aggregates at the plasma membrane. Ilk might reorganize and/or attach F-actin to the plasma membrane in several ways. It has been shown that Ilk can interact with α- and β-parvin, which are members of a family of actin-binding proteins (Nikolopoulos & Turner, 2000; Olski et al., 2001; Tu et al., 2001; Yamaji et al., 2001) and that disruption of this interaction delays assembly of focal-adhesion sites, stress-fibre formation and cell spreading (Tu et al., 2001). Ilk can also bind paxillin, which interacts with vinculin and α-parvin (Nikolopoulos & Turner, 2000). Interference with the paxillin–α-parvin interaction also impairs cell adhesion and cell spreading. Finally, Ilk can bind Pinch, which in turn recruits Nck2, an SH2/SH3-containing adaptor protein (Tu et al., 1999). Nck2 is present in cell adhesion sites (Zhang et al., 2002) and can bind Wasp (Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein) and Pak (p21-activated serine/threonine kinase), which modulate actin by Rac- or Cdc42-dependent or -independent mechanisms. Nck2 can also bind Dock180 (180-kDa protein downstream of CRK; Tu et al., 2001), which has been shown to modulate Rac activity. We are now testing whether Ilk binding partners are expressed in cartilage and, if they are, we will study their function using mouse genetics.

Another striking phenotype was the reduced proliferation rate of Ilk-null chondrocytes. Decreased phosphorylation of GSK3-β and Pkb/Akt might explain this defect. GSK3-β can be phosphorylated by Ilk (Delcommenne et al., 1998) and through Wnt signalling, resulting in the inactivation of GSK3-β, the stabilization of β-catenin and formation of β-catenin–lymphoid-enhancing-factor-1–T-cell-factor complexes. These complexes translocate to the nucleus and activate the expression of target genes, including those encoding cyclin D1 and c-Myc (Wu & Dedhar, 2001). It has been suggested that activation of Pkb/Akt is achieved by its phosphorylation at Thr308 by Pdk1 (Lawlor & Alessi, 2001) and at Ser473 by Ilk (Delcommenne et al., 1998). A bona fide kinase activity of Ilk has been questioned recently, owing to the results of genetic experiments in Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans, and biochemical experiments in mammalian cells. A lack of Ilk in Drosophila and of the Ilk homologue, PAT-4 (paralysed, arrested elongation at twofold-4), in C. elegans leads to defects in muscle attachment and lethality (Zervas et al., 2001; Mackinnon et al., 2002). Surprisingly, the Drosophila phenotype was not associated with the ectopic apoptosis observed during embryogenesis in Akt-deficient flies (Staveley et al., 1998). In addition, the loss-of-function phenotypes in Drosophila and C. elegans were completely rescued by a kinase-dead Ilk construct. Finally, two biochemical studies have ruled out the possibility that Ilk is a Pkb/Akt Ser473 kinase in mammalian cells (Lynch et al., 1999; Hill et al., 2002). Consistent with the observations described above, we found normal phosphorylation of GSK3-β and Pkb/Akt in Ilk-null chondrocytes. These findings suggest that Ilk is not essential for the phosphorylation of Pkb/Akt in chondrocytes in vivo, and that the reduced proliferation rate of Ilk-deficient chondrocytes is probably caused by decreased adhesion and abnormal cell shape, rather than by impaired modulation of GSK3-β or Pkb/Akt. It has been shown that cellular geometry is essential for cell growth and survival (Chen et al., 1997). Human capillary endothelial cells that are prevented from undergoing cell spreading show abolished progression through G1, associated with reduced cyclin-D1 protein levels (Huang et al., 1998). Similarly, disruption of the actin cytoskeleton also causes downregulation of cyclin D and blocks S phase by a mechanism that is independent of mitogen-activated protein kinase (Huang & Ingberg, 2002). As we observed decreased numbers of cyclin-D-positive chondrocytes in Col2–Ilk growth plates, decreased BrdU incorporation both in vivo and in vitro and extreme changes in shape and actin organization, it is tempting to speculate that cell geometry and the cytoskeleton have crucial functions in G1–S transition in chondrocytes.

Yeast-two-hybrid and co-immunoprecipitation studies have shown interactions between Ilk and β1- and β3-integrins, which are both highly expressed in chondrocytes (Hannigan et al., 1996). Mice that lack αvβ3-integrin develop a bone phenotype that is caused by the abnormal functioning of osteoclasts (McHugh et al., 2000). The function of chondrocytes, however, is not affected in these mice. By contrast, mice with a chondrocytespecific deletion of the β1-integrin gene (A.A. & R.F., unpublished data) show, as do Col2–Ilk mice, abnormal chondrocyte shape and reduced chondrocyte proliferation. In addition to these defects, however, loss of β1-integrin expression results in defective chondrocyte cytokinesis and impaired assembly of the collagen type II network. This suggests that Ilk mediates some, but not all, β1-integrin functions in chondrocytes.

In summary, our study supports the emerging view that the kinase activity is not essential for Ilk function, and suggests that, as in Drosophila and C. elegans (Zervas & Brown, 2002), Ilk acts primarily as an adaptor protein between integrin adhesion sites and actin.

Methods

Generation of conditional knockout mice.

The Ilk gene was isolated from a 129sv phage P1 artificial chromosome library. The targeting construct consisted of 2.7-kb left arm, a single loxP site, a 0.8-kb genomic fragment, a neomycin–thymidine kinase (neo–tk) cassette, flanked by loxP sites, and a 5.7-kb right arm. The construct was electroporated into R1 embryonic stem (ES) cells, and two ES-cell clones that underwent homologous recombination were used to produce germline chimaeras, as described previously (Fässler & Meyer, 1995). For chondrocytespecific deletion of Ilk, mice that carry a loxP-flanked Ilk gene were crossed with transgenic mice expressing the Cre recombinase under the control of regulatory regions from the mouse collagen type II (Col2a1) gene (Sakai et al., 2001).

For PCR genotyping, the following primers were used: Ilkf (specific for exon 1), 5′-GTCTTGCAAACCCGTCTCTGCG-3′; Ilkr (specific for intron 1), 5′-CAGAGGTGTCAGTGCTGGGATG-3′; Cref, 5′-AACATGCTTCATCGTCGG-3′; Crer, 5′-TTCCGATCATCAGCTACACC-3′.

Antibodies.

For immunological studies, the following antibodies were used: anti-collagen-type-II, anti-collagen-type-X, anti-aggrecan (Aszódi et al., 1998); anti-Ilk and anti-paxillin (Transduction Laboratories); anti-vinculin (Sigma); anti-Akt, anti-Thr308-Akt and antiser473-Akt (all from Cell Signaling); anti-GSK3-β (Transduction Laboratories); anti-Ser9-GSK3-β, anti-FAK and anti-Tyr397-FAK (Biosource Intl); anti-cyclin-D (Santa Cruz); and anti-β1-integrin. Actin and microtubules were detected using Cy3-conjugated phalloidin (Sigma) and an antibody reacting with α-tubulin (clone YL1/2), respectively. For flow cytometry, rat monoclonal antibodies against mouse β1- and β3-integrin subunits (PharMingen) were used.

Skeletal analysis.

Skeletal staining with alcian-blue/alizarin-red, histochemistry, immunostaining and in situ hybridization were carried out as described previously (Aszódi et al., 1998). Apoptotic chondrocytes were detected using the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche Diagnostics). Cell proliferation was analysed using the BrdU incorporation assay (Aszódi et al., 1998).

Isolation of and assays using primary chondrocytes.

Chondrocytes from rib or limb cartilage were released from newborn control or Col2–Ilk mice by digestion with collagenase type II (Worthington) at 2 mg ml−1 in DMEM, 2% FCS, at 37 °C for 2–4 h. Adhesion assays were carried out using standard procedures.

For cell spreading, primary chondrocytes were seeded in DMEM supplemented with 1.5% FCS on glass Lab-Tek chamber slides (Nalge Nunc Intl) coated with fibronectin. Cells were allowed to spread for 3 days and were then immunostained. For measurement of cell proliferation, chondrocytes were seeded at a density of 5 × 102 cells per well in 96-well plates, synchronized by serum depletion for 24 h and cultured with DMEM, 10% FCS for up to 7 days. Cell proliferation was analysed using the BrdU Cell Proliferation Elisa kit (Roche).

Western blotting.

RIPA extracts of primary chondrocytes isolated from newborn limb cartilage were boiled in reducing sample buffer, separated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and blotted on polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Amersham). Blocking, incubation with antibodies and washing were carried out in accordance with instructions of the supplier of the primary antibody. Immunoblots were developed using the ECL detection system (Amersham).

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Brakebusch for careful reading of the manuscript and the Ph.D. students of the Fässler lab for discussions. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB413), the Max Planck Society and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

References

- Alessi D.R. et al. (1997) 3-Phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (PDK1): structural and functional homology with the Drosophila DSTPK61 kinase. Curr. Biol., 7, 776–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aszódi A., Chan D., Hunziker E.B., Bateman J.F. & Fässler R. (1998) Collagen II is essential for the removal of the notochord and the formation of intervertebral discs. J. Cell Biol., 143, 1399–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.S., Mrksich M., Huang S., Whitesides G.M. & Ingber D.E. (1997) Geometric control of cell life and death. Science, 276, 1425–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcommenne M., Tan C., Gray V., Rue L., Woodgett J. & Dedhar S. (1998) Phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase-dependent regulation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 and protein kinase B/AKT by the integrin-linked kinase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 11211–11216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fässler R. & Meyer M. (1995) Consequences of lack of β1-integrin gene expression in mice. Genes Dev., 9, 1896–1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannigan G.E., Leung-Hagesteijn C., Fitz-Gibbon L., Coppolino M.G., Radeva G., Filmus J., Bell J.C. & Dedhar S. (1996) Regulation of cell adhesion and anchorage-dependent growth by a new β1-integrin-linked protein kinase. Nature, 379, 91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill M., Feng J. & Hemmings B. (2002) Identification of a plasma membrane Raft-associated PKB Ser473 kinase activity that is distinct from ILK and PDK1. Curr. Biol., 12, 1251–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S. & Ingberg D.E. (2002) A discrete cell cycle checkpoint in late G1 that is cytoskeleton-dependent and MAP kinase (Erk)-independent. Exp. Cell Res., 275, 255–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S., Chen C.S. & Ingberg D.E. (1998) Control of cyclin D1, p27Kip1, and cell cycle progression in human capillary endothelial cells by cell shape and cytoskeletal tension. Mol. Biol. Cell, 9, 3179–3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes R.O. (2002) Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell, 110, 673–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawlor M.A. & Alessi D.R. (2001) PKB/Akt: a key mediator of cell proliferation, survival and insulin responses? J. Cell Sci., 114, 2903–2910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch D.K., Ellis C.A., Edwards P.A. & Hiles I.D. (1999) Integrin-linked kinase regulates phosphorylation of serine 473 of protein kinase B by an indirect mechanism. Oncogene, 18, 8024–8032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackinnon A.C., Qadota H., Norman K.R., Moerman D.G. & Williams B.D. (2002) C. elegans PAT4/ILK functions as an adaptor protein within integrin adhesion complexes. Curr. Biol., 12, 787–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh K.P., Hodivala-Dilke K., Zeng M.H., Namba N., Lam J., Novack D., Feng X., Ross F.P., Hynes R.O. & Teitelbaum S.L. (2000) Mice lacking β3 integrins are osteoclerotic because of dysfunctional osteoclasts. J. Clin. Invest., 105, 433–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolopoulos S.N. & Turner C.E. (2000) Actopaxin, a new focal adhesion protein that binds paxillin LD motifs and actin and regulates cell adhesion. J. Cell Biol., 151, 1435–1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolopoulos S.N. & Turner C.E. (2001) Integrin-linked kinase (ILK) binding to paxillin LD1 motif regulates ILK localization to focal adhesions. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 23499–23505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olski T.M., Noegel A.A. & Korenbaum E. (2001) Parvin, a 42-kDa focal adhesion protein, related to the β-actinin superfamily. J. Cell Sci., 114, 525–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persad S., Attwell S., Gray V., Mawji N., Deng J.T., Leung D., Yan J., Sanghera J., Walsh M.P. & Dedhar S. (2001) Regulation of protein kinase B/Aktserine 473 phosphorylation by integrin-linked kinase: critical roles for kinase activity and amino acids arginine 211 and serine 343. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 27462–27469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai K., Hiripi L., Glumoff V., Brandau O., Eerola R., Vuorio E., Bösze Z., Fässler R. & Aszódi A. (2001) Stage- and tissuespecific expression of a Col2a1–Cre fusion gene in transgenic mice. Matrix Biol., 19, 761–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai T., Li S., Docheva D., Grashoff C., Sakai K., Kostka G., Braun A., Pfeifer A., Yurchenco P.D. & Fässler R. (2003) Integrin-linked kinase (ILK) is required for polarizing the epiblast, cell adhesion, and controlling actin accumulation. Genes Dev. (in the press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staveley B.E., Ruel L., Jin J., Stambolic V., Mastronardi F.G., Heitzler P., Woodgett J.R. & Manoukian A.S. (1998) Genetic analysis of protein kinase B (AKT) in Drosophila. Curr. Biol., 8, 599–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svoboda K.K.H. (1998) Chondrocyte–matrix attachment complexes mediate survival and differentiation. Microsc. Res. Technol., 43, 111–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Y., Li F., Goicoechea S. & Wu C. (1999) The LIM-only protein PINCH directly interacts with integrin-linked kinase and is recruited to integrin-rich sites in spreading cells. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 2425–2434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Y., Huang Y., Zhang Y., Hua Y. & Wu C. (2001) A new focal adhesion protein that interacts with integrin-linked kinase and regulates cell adhesion and spreading. J. Cell Biol., 153, 585–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. & Dedhar S. (2001) Integrin-linked kinase (ILK) and its interactors: a new paradigm for the coupling of extracellular matrix to actin cytoskeleton and signaling complexes. J. Cell Biol., 155, 505–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaji S., Suzuki A., Sugiyama Y., Koide Y., Yoshida M., Kanamori H., Mohri H., Ohno S. & Ishigatsubo Y. (2001) A novel integrin-linked kinase-binding protein, affixin, is involved in the early stage of cell–substrate interaction. J. Cell Biol., 153, 1251–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zervas C.G. & Brown N.H. (2002) Integrin adhesion: when is a kinase a kinase? Curr. Biol., 14, R350–R351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zervas C.G., Gregory S.L. & Brown N.H. (2001) Drosophila integrin-linked kinase is required at sites of integrin adhesion to link the cytoskeleton to the plasma membrane. J. Cell Biol., 152, 1007–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Chen K., Guo L. & Wu C. (2002) Characterization of PINCH-2, a new focal adhesion protein that regulates the PINCH-1–ILK interaction, cell spreading and migration. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 38328–38338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]