Abstract

Context: When certified athletic trainers (ATCs) enter a workplace, their potential for professional effectiveness is affected by a number of factors, including the individual's ability to put acquired knowledge, skills, and attitudes into practice. This ability may be influenced by the preconceived attitudes and expectations of athletes, athletes' parents, athletic directors, physical therapists, physicians, and coaches.

Objective: To examine the perspectives of high school coaches and ATCs toward the ATC's role in the high school setting by looking at 3 questions: (1) What are coaches' expectations of ATCs during different phases of a sport season? (2) What do ATCs perceive their role to be during different phases of a season? and (3) How do coaches' expectations compare with ATCs' expectations?

Design: Qualitative research design involving semistructured interviews.

Setting: High schools.

Patients or Other Participants: Twenty high school varsity basketball coaches from 10 high schools in 2 states and the ATCs assigned to these teams.

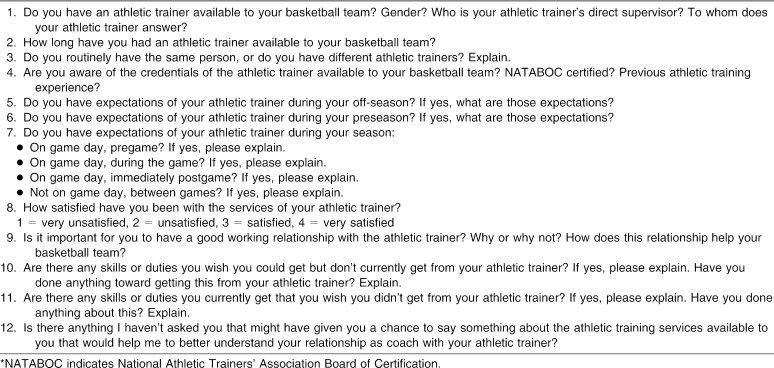

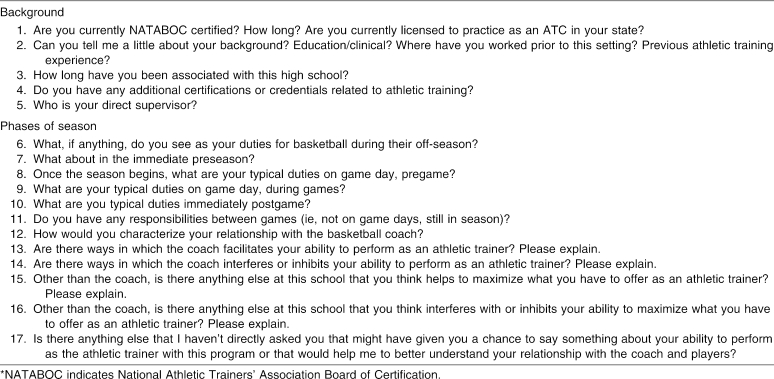

Main Outcome Measure(s): For the coaches, 12 questions focused on 3 specific areas: (1) the athletic training services they received as high school basketball coaches, (2) each coach's expectations of the ATC with whom he or she was working during various phases of the season, and (3) coaches' levels of satisfaction with the athletic training services provided to their team. For the ATCs, 17 questions focused on 3 areas: (1) the ATC's background, (2) the ATC's perceived duties at different phases of the basketball season and his or her relationship with the coach, and (3) other school factors that enhanced or interfered with the ATC's ability to perform duties.

Results: Three themes emerged. Coaches had limited knowledge and understanding of ATCs' qualifications, training, professional preparation, and previous experience. Coaches simply expected ATCs to be available to complement their roles. Positive communication was identified as a critical component to a good coach-ATC relationship.

Conclusions: Although all participants valued good communication, poor communication appeared to limit ATCs' contributions to player performance beyond simple availability. Coaches must be educated by ATCs to ensure they are receiving qualified athletic training support.

Keywords: athletic trainers' duties, athletic trainers' relationships, psychology

Athletic training professional preparation programs are designed to provide aspiring certified athletic trainers (ATCs) with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes required for competent professional practice. Once ATCs acquire certification from the National Athletic Trainers' Association Board of Certification (NATABOC) and meet state practice requirements, they enter an organization or workplace (eg, high school, college, sports medicine clinic). Once in an organization, their potential for professional effectiveness comes under the influence of a complex blend of factors. One factor is the ability of ATCs to put their acquired knowledge, skills, and attitudes into practice. This ability may be enhanced or limited by the preconceived attitude and expectations of athletes, athletes' parents, athletic directors, physical therapists, physicians, and coaches. Ultimately, contributions by all these participants warrant scrutiny. Initially, however, the viability of an approach to understanding the contributions of at least one participant is needed. The purpose of our exploratory research was to identify and contrast the perspectives of coaches and ATCs with regard to the role of the ATC in the high school setting.

Socialization offers a theoretic framework for studying professionals and their work. Analyses of physicians,1,2 physical education teachers,3–8 nurses,9–11 and ATCs12,13 provide models for using a socialization framework to study professionals and their roles. The socialization process is typically described in 3 phases.5,6,14 The first phase is anticipatory socialization, or recruitment, when career aspirants explore professional requirements and contrast these with their personal attributes (eg, high school career fairs, guidance counselor sessions, informal observations of professionals in daily life). The second phase, professional socialization, marks the time when aspirants enter formal programs (eg, accredited athletic training education programs, medical school, physical therapy school) designed to adjust initial impressions of a field to the socializing agents in the profession (eg, university faculty, approved clinical instructors, clinical supervisors). The final phase of the socialization process and focal point of this study occurs as individuals move into the work force and are organizationally socialized. During this final phase, individuals must adjust the ideals and theories they have learned in their professional socialization to the demands and imperfections of the real world.

Coaches have their own perceptions and ideas of what it is to be an ATC and what they want from their ATCs as they work with a team. These perceptions have developed over the years through their association with ATCs and sports teams while both playing and coaching. As seasons unfold, it would be reasonable to expect coaches to have specific expectations for ATCs during games, practices, off weekends, preseason, and postseason. These expectations can be influential in socializing ATCs into their professional roles. The coach-ATC relationship is very visible to prospective students looking at careers in both coaching and athletic training.

Exploring the relationship between high school coaches and ATCS may help us to explain how ATCs become socialized into the profession. To date, a limited number of researchers have examined the socialization of ATCs. Searches of the MEDLINE (1966–2004), SPORT Discus (1975–2004), and ERIC (1966–2004) databases revealed no research specifically looking at the relationship between ATCs and coaches. Review of the Journal of Athletic Training also revealed no examination of the relationship between ATCs and coaches.

The purpose of our study was to explore and contrast perspectives of coaches and ATCs toward the ATC's role in the high school setting. We investigated 3 main questions: (1) What are coaches' expectations of ATCs during different phases of a basketball season? (2) What do ATCs perceive their role to be during different phases of a season? and (3) How do the coaches' expectations compare with the expectations of the ATCs?

METHODS

Procedures

We used a criterion sampling strategy to identify potential participants.15,16 The criterion was that each participant (coach or ATC) had a working relationship in a high school setting. An initial informal contact was made with high school coaches and ATCs to determine their level of interest and appropriate procedures for conducting research within their school district. Initially, we started with a predetermined number of 20 coaches and their 10 ATCs based on their locations. Exhaustion of the data and saturation of the categories ultimately caused us to stop seeking new participants.16 Appropriate institutional review board approval for human subjects was granted by the school districts and the sponsoring university.

Upon agreeing to participate, each coach and ATC signed an informed consent and arranged a time to complete a semistructured interview. Interviews were tape recorded (with permission) and took approximately 30 minutes. Each interview followed a semistructured questionnaire format. The interview questions were designed to elicit information about the relationship between coaches and the ATCs assigned to their high schools. Questions specifically examined the coach-ATC relationship during different phases (preseason, season, off-season) of a basketball season. Each phase of the basketball season represents a specific time period when ATCs offer distinct services to a high school and, more specifically, a sport team. To determine how effective an ATC can be in a high school setting, it is essential to first understand the expectations of both coaches and ATCs and then compare them. One set of questions guided interviews with all the coaches (Appendix A), and one set of questions guided interviews with all ATCs (Appendix B). Each participant was given the chance to expand on any answer to provide more insight into his or her coach-ATC relationship. To protect the identity of the participants and high schools, pseudonyms are used throughout the study.

APPENDIX A. Interview Guide: Coaches*.

APPENDIX B. Interview Guide: Certified Athletic Trainers*.

Participants

Twenty high school basketball coaches and 10 ATCs from 2 states (Indiana and Alabama) participated in a semistructured interview as part of this study. Participants consisted of 10 boys' basketball coaches (all male), 10 girls' basketball coaches (5 males, 5 females), and their respective ATCs (6 males, 4 females). Each coach had a current professional relationship with the ATC assigned to his or her high school.

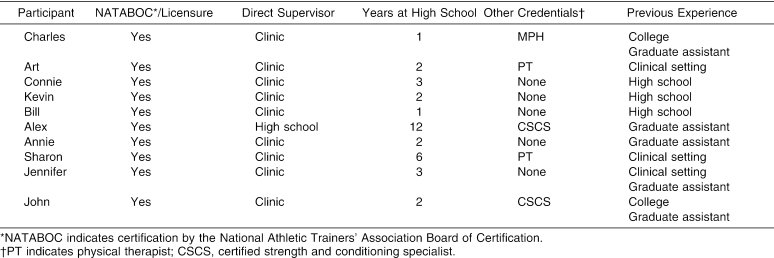

Seven high schools were class 4A, 1 was class 3A, 1 was class 1A, and 1 was class 5A, with the 2002–2003 enrollments of the 10 schools ranging from 500 to 2059 students. Each high school offered between 12 and 21 varsity sports throughout the academic school year. All 10 ATCs were white, and 9 of the 10 were hired by a sports medicine clinic and sent out to provide high school coverage. One ATC was also a full-time teacher. See Table 1 for pertinent participant demographic information on the ATCs.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Athletic Trainers.

Design

A qualitative research design was used for this exploratory study. Patton15 suggested that a qualitative process study is appropriate when the researcher aims to “understand the internal dynamics of how a program, organization, or relationship operates.” Because so little is known about the interaction between coaches and ATCs, a qualitative process study approach had the greatest potential to illuminate important aspects of this working relationship.

Instrument

Data were collected using an in-depth, semistructured interview with coaches and ATCs. Before data collection, we thoroughly examined and pilot tested the interview formats with 3 coaches and 3 ATCs. Interviews were conducted by 2 NATABOC-certified ATCs. Interviewers were currently practicing as ATCs and had been certified for at least 4 years. Their backgrounds in athletic training allowed for in-depth probing of participant answers as they pertained to athletic training.

Twelve questions were finalized and asked of each basketball coach, focusing on 3 specific areas (see Appendix A). The first group of questions centered on the athletic training services they received as high school basketball coaches. The second set of questions was designed to elicit the coaches' expectations of the ATCs with whom they were working during various phases of the season. In the final set of questions, coaches were asked to express their level of satisfaction with the athletic training services provided to their teams. The questions were related to the study in that they identified the subjects' knowledge of ATCs and then assessed to what extent they believed their ATCs were beneficial to their programs.

The ATCs' interviews consisted of 17 questions, again focusing on 3 major areas (see Appendix B). The first group of questions focused on the backgrounds of the ATCs. The next set examined the perceived duties of the ATCs with respect to different phases of the basketball season and their relationships with their coaches. The final group of questions examined other factors at the school that enhanced or interfered with the ability of the ATC to perform duties.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using a grounded theory approach.17 A grounded theory approach allows researchers to analyze unstructured data, such as text from an interview, to identify and explore complex relationships. In this study, we used open, axial, and selective coding as part of the data-analysis process.17 The first step (open coding) was to code single transcribed sentences or ideas (text units) from each interview and organize them into common categories. The next step was to build connections within each category (axial coding). This involved examining and comparing categories to see if they were interrelated. The final step of the analysis involved a comparison of common categories and their integration into the larger theoretic framework of the study (selective coding).

Trustworthiness of the results was established by peer debriefing (data-analyst triangulation).16 Peer debriefing is designed to have independent analysts review the interview data and construct categories for accuracy and consistency. In our study, 3 ATCs, all with graduate degrees, independently analyzed the interview data to probe for research bias and clarify interpretations. Each independent analyst had an MS degree in kinesiology with formal education in research methodology (at least 3 graduate courses). In addition, each coder attended a 1-hour training session that outlined appropriate qualitative-research methods, specifically data analysis. These were informal training sessions used to discuss qualitative-research methods and answer any questions from the coders.

RESULTS

The results are presented in 3 major categories. The first section includes information pertaining to the coaches' limited knowledge of ATCs' qualifications. The second section is a description of coaches' expectations regarding ATCs' availability and accessibility. The third section identifies communication as a significant aspect of the coach-ATC relationship.

Coaches' Knowledge of Athletic Trainers' Qualifications

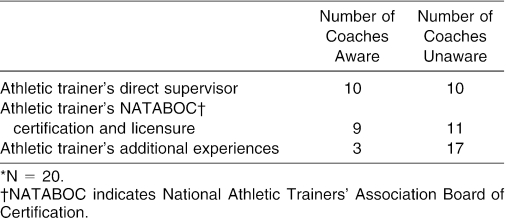

A coach's perception of his or her ATC's background and direct supervisor was inconsistent with the information stated by the ATC (Table 2). Ten of the 20 coaches identified a clinical supervisor who was inconsistent with that stated by their ATC. Eight coaches indicated that they had no idea who their ATC's direct supervisor was, and 2 coaches indicated that they were the direct supervisors. Ten coaches were consistent with their ATCs in identifying the direct supervisor.

Table 2. Coaches' Knowledge of Their Athletic Trainers' Backgrounds*.

Eleven of the 20 coaches did not know their ATCs' credentials or if they were NATABOC certified. When asked if the ATC working with his team was certified, Coach Wilson replied, “I don't remember. He told me some things but I don't remember.” Other coaches were very direct in stating that they had no idea whether or not their ATCs were certified. When specifically asked about their ATCs' certification credentials, 6 coaches stated, “I don't know.” In reality, all 10 ATCs were NATABOC certified, and all were licensed to practice in their states.

Seventeen of the 20 coaches were unaware of any related athletic training experience of their ATCs. When asked about the previous experiences of the ATC, Coach Miller said, “No we've never had that conversation.” Coach Wilson was unclear about the past experiences of his ATC. When asked about it, he replied, “I am not sure. I know he works other places and he has told me about some other places that he has worked, but again details I don't know right now.” When asked about the experience of the athletic trainer working with his team, Coach Grant replied, “I really don't know to be frank with you. What I look at basically is whether they [ATCs] are getting the job done and they [ATCs] seem pretty knowledgeable in what they are doing.” Other coaches simply stated that they had no idea of any previous athletic training experiences by the ATCs working with their teams.

Athletic Trainers' Availability and Accessibility

Coaches' Perceptions

Off-season expectations of coaches were nearly unanimous: They simply wanted their ATCs to be available. Coaches expressed a need to have ATCs around to give advice and to complement what the coaches do. For example, when asked about off-season expectations of the ATC, Coach Miller said, “It is important to know where he [ATC] is and how to get ahold of him.” Coach West indicated that he wants the ATC “to be available if I have some questions as far as an injury to a kid or the prevention of an injury to a kid. It would be nice to have a phone number or something, an e-mail address. That would be about it.” Coach Fox simply stated that he wants the ATC “just to be available in the off-season.”

During the preseason, accessibility was again a main concern of the high school coaches. Coach Fox suggested that his expectations for the preseason were “similar to the off-season” and added “as long as they [ATCs] are available for us [coaches], it is not a problem.” When asked about his expectations for the ATC during the preseason, Coach Grant indicated that his expectations were “the same during preseason [as off-season] since our athletic trainer is spread pretty thin.” Most coaches indicated a general sense of wanting availability during the preseason by statements such as “[ATC] being in a general vicinity” or “[ATC] providing availability, especially to the athletes themselves.” Coaches understood that ATCs may still be working with fall sports and realized that the ATC could not be in 2 places at once. Similarly, being able to give advice and enhance what the coaches were doing were also mentioned as expectations during the preseason.

Coaches were better able to articulate specific duties for their ATCs during the season. Specific expectations included taping and stretching athletes before the game and taking care of any injured athletes. For example, when asked if he had any expectations of his ATC during the season, Coach Grant replied, “Yes I do. If there is any taping that needs to be done, if there are any injuries that need to be addressed at that particular time.” Coach West spoke of his expectations of an ATC during the season and before a game as “a time when the kids, if they need stretched [sic] a certain way or something needs to be looked at or if anything needs to be taped, or if there is something that an individual needs in order to get them through the game.” When asked about what he expected of his ATC before a game, Coach Jessup said, “basically that they [ATCs] are here an hour before the game or during the JV game and make themselves available after the game if somebody has something [an injury].” Coaches were able to identify specific pregame duties for ATCs that centered on 3 areas: being available to tape, stretch, or take care of any injury before the game. Next, coaches wanted their ATCs to sit on the bench and take care of anything that might happen during the game. However, the interview data overwhelmingly supported the coaches' need to have their ATCs simply be available. Specific comments for each included, “We just like for him [ATC] to be there,” “We hope that he [ATC] is right there to be available,” “Right there ready to pounce on any situation that may arise immediately,” “Just as long as they [ATCs] are at the end of the bench,” “I want him [ATC] on the end of the bench,” and “If there is an injury, that he [ATC] is basically there.”

Nine of the interviewed coaches stated there were no other duties they wished their ATCs would perform beyond services already provided. Eleven coaches identified specific duties they wished their ATCs would perform. Examples of these duties included implementing a weight-room conditioning program, nutrition program, and consistent stretching routine; establishing a coach's clinic; and traveling to away games. Of the 11 coaches who wished for more from their ATCs, only 1 stated he had done anything about getting it. One coach responded that he believed his ATC was too conservative with injuries, and this conservative approach bothered the coach. The coach went on to say that he had not approached the ATC about addressing this problem.

Athletic Trainers' Perceptions

Certified athletic trainers identified their major off-season duties as consisting of implementing a conditioning program and performing any rehabilitation programs for injured athletes. For example, when asked about the off-season, Charles said, “I think off-season at the high school is an important time to make sure they [athletes] are working on their overall conditioning and strengthening. I think my duty is to facilitate those kids who are not in another sport and make sure they are staying in shape and [have] a good flexibility program, so when basketball season becomes in season that they are where they need to be.” Specific off-season duties were also described by Art, who said “I have a lot of postseason work, rehabilitation wise. I do a lot of that [rehabilitation] after the season is done. They [coaches] have also approached us on off-season conditioning for the athletes.” Connie indicated that her responsibility during the off-season includes “helping the coaches coordinate their conditioning and strengthening programs and work[ing] with athletes as they get hurt when they are playing in their club season.”

Preseason duties were similar to those during the off-season. Duties such as strength and conditioning programs, flexibility programs, and rehabilitation of injured athletes were identified. For example, Charles indicated that “it is really important to make sure that preventative stretching and pre and post stretching is a very big part of their routine [during preseason] and helping coaches teach a good stretching program.” Kevin compared his duties during the off-season and preseason as the “same sort of thing, basically injury recognition, evaluation, and treatment [of injuries] if something occurred.” Art indicated that, during the preseason, he is “approached with general questions about stretching, strengthening, preseason calisthenics, just getting in shape and what is the best way, and what is the best time management for athletes.” Each ATC spoke of his or her role during the preseason in specific terms, similar to his or her comments pertaining to the off-season.

Athletic trainers also perceived taping, stretching, and dealing with injuries as a major role during the season and specifically during games. Charles spoke of his pregame routine as “getting there approximately an hour and a half before the competition begins to do whatever taping or whatever treatments are necessary for the kids to play.” He also noted additional expectations that were very important to him, and they included “acting as a liaison for the athletic department in meaning that when the other schools get there, I try to meet them and make sure they have access to water and ice if they need to do that. I also make sure I introduce myself to the coaching staff of the other team.” Connie also spoke of communicating with the other team as one of her expectations. When asked about her pregame responsibilities, she said, “I usually get to the game about 45 minutes before the game, set up the trainer's station with water and ice, tape any athletes from either school that need taped [sic] and really settle in to watch the game if something happens.” An additional responsibility during and after a game that ATCs spoke of was communicating with the parents pertaining to any injury or illness that happened during the game. Bill indicated that “managing any injuries that happen during a game, contacting parents, and talking to parents about it if their kid got hurt during the game” was a typical duty for him as an ATC.

When asked about his role as an ATC immediately after the game, Charles said, “If there would happen to be any injuries, I would make sure I have educated the athlete about what's going on, the signs and symptoms to watch out for, and send them home with my business card in case their parents have any questions.” He also indicated that in the event of a more serious injury, he would “have direct parental contact to make sure that everything is on the same page.” Additional game-time duties that ATCs spoke of included providing water to the athletes and supervising the cheerleaders and the junior varsity games and practices.

Coach-Athletic Trainer Communication

All coaches were more than satisfied with their ATCs with respect to their basketball programs, with 13 coaches being very satisfied. All 20 coaches stated it was important to have a good working relationship with their ATC. Coach Fisher discussed the importance of having an open relationship with her athletic trainer. She stated, “I trust what he says and he trusts what I say and we can work together.” Coach Fox also discussed the importance of a quality relationship and said, “It helps the kids see that it is not just the coach taking care of them, but another staff member [ATC], someone who knows what they are talking about.” Coach Webb stated that “A good relationship is very important and we need to be on the same page with injury situations.”

When asked about their relationship with coaches, all 10 ATCs stated that they had a good professional relationship. Charles discussed the difference between the girls' coach, who “is much younger and understands that I am trying to help the kids,” and the boys' coach, who “is not used to having somebody there.” Kevin also discussed that his relationship was “probably a little bit better with the boys' coach, he is a little more personable and understands what an athletic trainer does.” He went on to say, “The girls' coach, I don't know if he doesn't see a need for me to be there or just doesn't understand my function.” Annie indicated that “We [coach and ATC] understand what each other's role is and it has not been a problem working together at all.” John stated that his relationship with a coach is “critical for the success of the team and I sometimes don't know if all coaches realize that.”

All but 1 ATC stated that the coaches at their high schools facilitated their ability to perform as ATCs. Coaches did not interfere with the ATCs' performance of their duties at the high schools. The ATCs overwhelmingly stated that their athletic director helped to maximize their jobs at the high schools. Other individuals mentioned by participants who maximized the ATC's job at the high school were principals, athletic secretaries, and facilities and maintenance people.

DISCUSSION

We will use the 3 questions guiding this study to frame the results of the semistructured interviews with high school basketball coaches and their ATCs.

Coaches' Expectations of Athletic Trainers

The coaches generally had minimal expectations of their ATCs during all phases of the basketball season. Availability was their primary expectation. During the season, however, the coaches' expectations were a bit more demanding and included taping athletes, stretching exercises, and treating acute injuries. These findings should not be surprising because coaches had little to do with hiring the ATCs and had little, if any, information about the qualifications, knowledge, or skills of the ATCs assigned to their teams.

A coach's limited perception of what an ATC can do may be attributed to a lack of knowledge or personal experience with an ATC in a high school setting. Providing undergraduate and graduate athletic training students with required clinical rotations at high schools may help to educate coaches regarding the skills of ATCs. Organizational socialization literature in nursing and physical therapy suggests that a primary purpose of an education program is to help students assimilate the values and experience an authentic preview of a particular work setting.18 Coaches who gain more experience with competent ATCs and athletic training students on a continual basis might become more informed as to the skills and abilities ATCs can offer their teams.

Athletic Trainers' Expectations of Their Role

In contrast with coaches, ATCs provided detailed accounts of their perceived roles and responsibilities during all phases of a basketball season. During the off-season and preseason, specific tasks related to strength and conditioning, rehabilitation programs, injury recognition, and evaluation and treatment of injuries were identified. The intensity of training increases for athletes as the season approaches and so too do the responsibilities of the ATC.

Major roles during the season involved the predictable duties of taping, stretching, and dealing with injuries. Less obvious to casual observers are the program ambassador duties. For example, facilitating the care and prevention needs of visiting teams and communicating with the parents of injured athletes and athletes themselves were described as position responsibilities. The detailed description of duties described by ATCs was clearly linked to the educational knowledge and skills they received as students during their professional training.

Contrasting Coaches' and Athletic Trainers' Perceptions

Coaches' perceptions regarding the role of athletic trainers were quite consistent and different from those perceptions held by their ATCs. Coaches wanted their ATCs to be available and could rarely describe their needs more explicitly. In contrast, ATCs described explicit duties differentiated by phases of the sport season.

The fact that many coaches may not recognize the variety of contributions ATCs can make to the health care success of a team can be problematic. First, a potentially valuable resource is not being used. The ATCs have a great deal of knowledge and skills pertaining to the prevention, care, and management of athletic injuries. Second, ATCs' job satisfaction (related to job effectiveness) can be jeopardized. When ATCs acquire one set of role performance expectations from their professional education and experience a different set of expectations on the job, the seeds of discontent are sewn. From these seeds grow the probabilities for role ambiguity and role conflict. Research in organizational socialization suggests that role ambiguity and role conflict are the most consistent predictors of job satisfaction and commitment.19 In other words, an ATC who is unable to clearly define his or her role or feels underappreciated may be more likely to experience burnout and leave the profession. In other allied health professions, high attrition rates, lack of participation in professional organizations, and the disparity of the allied health professionals' roles may all be linked to how well students are socialized into the profession.20 It has been suggested that, without appropriate socialization, students are trained with the “tools of the trade” without being expected to become members of the profession.20

Coaches are key members of the sports medicine team and have a great deal of interaction with ATCs at all levels of competition. They have the ability to provide ATCs with a great deal of knowledge about their current employment setting and make their jobs much easier in many respects. Literature in athletic training socialization suggests that informal socialization methods are the primary means by which ATCs learn about their roles in work settings.12,13 Pitney et al12,13 suggested that athletic training education programs would be well served to provide more informal learning situations in which students can learn through trial and error in a more independent learning environment. This type of informal learning would include establishing positive working relationships with coaches and other allied health professionals. In the high school setting, Pitney13 stated that, “ATCs were able to gain an understanding of their responsibilities by obtaining feedback from the coaches they worked with.” The fact that coaches had very little information about their ATCs suggests that ATCs in this study might not have optimally utilized their coaches.

Limitations

The coaches and ATCs who participated in this study were from a small, purposeful, nonrandom sample that may influence the ability to generalize the results. Participants were limited to high school basketball coaches and ATCs from 2 states. This study was exploratory and designed to provide an initial understanding of the coach-ATC relationship.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The ATCs who are contracted for services at a high school immediately begin at a disadvantage caused by not being present throughout the day at the high school. These ATCs are unfamiliar faces during the school day and typically only arrive at the high school in the afternoon for coverage of events and practices. To enhance the process of effective communication, the clinic that contracts ATCs to a high school should implement a coaches' clinic to discuss the duties and qualifications of the ATCs.

Effective communication skills must be emphasized and practiced in both the clinical and didactic portions of athletic training education programs. This may include a formal course, clinical competency, or direct learning experience in how to foster appropriate communication with a variety of individuals associated with sports medicine (eg, coaches, athletic directors, physicians, physical therapists). As with most skills, effective communication must first be learned, then practiced, and finally implemented into a realistic clinical experience. A valuable learning experience for both parties occurs when students are responsible for initiating and maintaining appropriate communication with coaches regarding a variety of issues.

Future Research

As is true with most descriptive studies of new areas in any field, this effort has resulted in more questions than answers. A related extension would involve examining how ATCs are socialized into different sports and settings. For example, are the expectations of football coaches similar to or different from those of basketball coaches and coaches of other sports? And to what extent do expectations of high school coaches match up with those of college coaches, professional coaches, or clinical supervisors? Does the sex of the coach or the athletes affect these expectations?

In this study, the perspectives of high school coaches were contrasted with those of ATCs. Many others may play important roles in shaping an ATC's role during the organizational socialization phase. For example, physicians, physical therapists, and athletic directors and administrators may influence what ATCs do. In what ways do these professional colleagues influence the performance of ATCs? These and other questions remain to be asked and answered. We hope this research study will initiate both reflection and future discourse on factors that influence the socialization and performance of ATCs.

CONCLUSIONS

Certified athletic trainers are hypothesized to progress through different stages of socialization en route to becoming professionals.1–14 During the organizational socialization phase, the performance of ATCs is influenced by a variety of competing perspectives, including those held by athletic directors, peer ATCs, and coaches.

Three main conclusions may be drawn from the results of this study. First, these high school basketball coaches described a perspective of the ATCs' roles that is, at best, incomplete. The ATCs stated specific details of their daily jobs at the high school, whereas the coaches did not discuss any specifics with respect to the medical coverage provided by the ATCs at their high schools.

Second, these coaches were relatively uninformed about the credentials and, subsequently, the specific services ATCs can provide their athletic teams. Inconsistencies in the perception of the qualifications and specific roles of ATCs in the high school setting hinders the coach's ability to benefit from the medical services available from an ATC.

Third, authentic communication between coaches and their ATCs was an issue. Despite the fact that both ATCs and coaches emphasized the importance of positive communication, a lack of communication between these individuals perpetuated the inconsistencies and undermined the level of service ATCs could provide in the high school setting.

Implications

Clear implications of our findings may be vital for coaches, ATCs, administrators, parents, and athletes to understand. First, educating high school coaches about specific duties that ATCs can provide for their teams is essential if high school athletes are to fully benefit from all of their medical services. Certified athletic trainers possess a wide variety of knowledge and skills that can potentially benefit both athletes and coaches. The breadth and depth of skills and knowledge outlined in the 1999 Athletic Training Educational Competencies21 and required by Commission on Accreditation of Allied Health Education Programs-accredited athletic training programs go far beyond the superficial expectations coaches in this study had of their ATCs. The limited perception of coaches pertaining to what ATCs do also falls far short of the actual duties and roles of an ATC outlined in the 2004 Role Delineation Study.22 When ATCs are providing a wide variety of health care services to benefit the athlete, high school, and community, they are being used to their optimal capacity. Such optimal utilization is not being achieved at the venues in this study.

To take full advantage of the potential services available from ATCs, each coach needs to be properly educated. Learning to interact with and ultimately educate coaches is a process of informal learning that can take many years to perfect and is not directly taught in undergraduate athletic training programs. The work of Pitney et al12,13 on professional socialization in both the high school and collegiate setting suggests that informal learning is critical for both undergraduates and practicing ATCs. Informal learning helps foster and enhance self-direction, reflection, and critical-thinking skills. Additional research in athletic training education suggests that authentic experiences (eg, interactions with a coach) enhance student learning for undergraduate athletic training students.23

The educational experiences future ATCs are exposed to must provide an accurate preview of the arenas in which they may ultimately practice. In a classic study of professional socialization, Becker et al1 found that it is critical for educational programs and their students to be more realistic and less idealistic in what to expect in an actual setting. Providing students with multiple opportunities to interact with coaches during their professional preparation gives students more chances to enhance their communication skills. An additional benefit is that coaches may be informally educated (socialized) about the high level of knowledge and skills ATCs possess. Research in nursing indicates that a strong and clear identity developed through professional socialization helps to enhance personal self-esteem and detracts from the negative influences of the public image of nurses.24 Similarly, ATCs must leave their professional programs and enter the work setting with a strong and clear identity of what it is to be an ATC and display this vision clearly to all allied health professionals and potential colleagues.

Finally, identifying the qualifications of an ATC working at a high school should be important to all coaches at that high school. Foremost, it should be known if the athletic trainer is NATABOC certified and licensed to practice as an ATC in the state. High schools should be more involved in the hiring process of ATCs through the sports medicine clinic. The athletic administration and coaching staff should also be aware of the past experiences of their ATCs, especially as they relate to different levels of competition (eg, high school, collegiate, professional) and past sport coverage. An ATC at a high school is often the only trained allied health professional available during practices and games and, therefore, becomes the ultimate decision maker for the medical well-being of an injured athlete. An ATC with no previous high school experience may be less prepared to deal with this level of autonomy and the subsequent problems specific to the high school athlete, high school coach, and parents of these athletes.25

REFERENCES

- Becker HS, Geer B, Hughes EC, Strauss AL. Boys in White: Student Culture in Medical School. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago; 1961.

- Hunt CE, Kallenberg GA, Whitcomb ME. Trends in clinical education of medical students: implications for pediatrics. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:297–302. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtner-Smith MD. The occupational socialization of a first-year physical education teacher with a teaching orientation. Sport Educ Soc. 2001;6:81–105. [Google Scholar]

- Templin TJ, Schempp PG. Socialization into physical education: its heritage and hope. In: Socialization into Physical Education: Learning to Teach. Indianapolis, IN: Brown & Benchmark; 1989:1–11.

- Lawson HA. Toward a model of teacher socialization in physical education, part 1: the subjective warrant, recruitment, and teacher education. J Teach Phys Educ. 1983;2:3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson HA. Toward a model of teacher socialization in physical education, part 2: entry into schools, teachers' role orientations, and longevity in teaching. J Teach Phys Educ. 1983;3:3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Pooley JC. Professional socialization: a model of the pre-training phase applicable to physical education students. Quest. 1972. pp. 57–66. XVIII.

- Pooley JC. The professional socialization of physical education students in the United States and England. Int Rev Sport Sociol. 1975;3–4:97–108.

- Coudret NA, Fuchs PL, Roberts CS, Suhrheinrich JA, White AH. Role socialization of graduating student nurses: impact of a nursing practicum on professional role conception. J Prof Nurs. 1994;10:342–349. doi: 10.1016/8755-7223(94)90037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesler MS, Hanner MB, Melburg V, McGowan S. Professional socialization of baccalaureate nursing students: can students in distance nursing programs become socialized? J Nurs Educ. 2001;40:293–302. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-20011001-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reutter L, Field PA, Campbell IE, Day R. Socialization into nursing: nursing students as learners. J Nurs Educ. 1997;36:149–155. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-19970401-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitney WA, Ilsley P, Rintala J. The professional socialization of certified athletic trainers in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I context. J Athl Train. 2002;37:63–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitney WA. The professional socialization of certified athletic trainers in high school settings: a grounded theory investigation. J Athl Train. 2002;37:286–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lortie D. Schoolteacher: A Sociological Study. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1975.

- Patton MQ. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1990.

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1985.

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Chicago, IL: Aldine; 1967.

- Teschendorf B, Nemshick M. Faculty roles in professional socialization. J Phys Ther. 2001;15:4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Adkins C. Previous work experience and organizational socialization: a longitudinal examination. Acad Mgmt J. 1995;38:839–862. [Google Scholar]

- Hayden J. Professional socialization and health education preparation. J Health Educ. 1995;26:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- National Athletic Trainers' Association. Athletic Training Educational Competencies. 3rd ed. Dallas, TX: National Athletic Trainers' Association; 1999.

- National Athletic Trainers' Association Board of Certification. Role Delineation Study. 5th ed. Omaha, NE: National Athletic Trainers' Association Board of Certification, Inc; 2004.

- Mensch JM, Ennis CD. Pedagogical strategies perceived to enhance student learning in athletic training education. J Athl Train. 2002;37:S-199–S-207. (suppl) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon B, Oh D, Choi C, Park Y. The relationship of professional socialization and the image of nurses among nursing students. Paper presented at: The Student Nurse: Stressors and Image; November 2, 2003; Seoul, Korea.

- Ray R, Weise-Bjornstal DM. Counseling in Sports Medicine. eds. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1999.