Abstract

Objective: To present the reader with various psychobehavioral characteristics of muscle dysmorphia, discuss recognition of the disorder, and describe treatment and referral options.

Data Sources: We conducted a comprehensive review of the relevant literature in CINAHL, MEDLINE, SPORT Discus, EBSCO, PsycINFO, and PubMed. All years from 1985 to the present were searched for the terms muscle dysmorphia, bigorexia, and reverse anorexia.

Data Synthesis: The incidence of muscle dysmorphia is increasing, both in the United States and in other regions of the world, perhaps because awareness and recognition of the condition have increased. Although treatment options are limited, therapy and medication do work. The primary issue is identifying the disorder, because it does not present like other psychobehavioral conditions such as anorexia or bulimia nervosa. Not only do patients see themselves as healthy, most look very healthy from an outward perspective. The causes of muscle dysmorphia are not well understood, which reinforces the need for continued investigation.

Conclusions: Muscle dysmorphia is an emerging phenomenon in society. Pressure on males to appear more muscular and lean has prompted a trend in the area of psychobehavioral disorders often likened to anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Athletes are particularly susceptible to developing body image disorders because of the pressures surrounding sport performance and societal trends promoting muscularity and leanness. Health care professionals need to become more familiar with the common signs and symptoms of muscle dysmorphia, as well as the treatment and referral options, in order to assist in providing appropriate care. In the future, authors should continue to properly measure and document the incidence of muscle dysmorphia in athletic populations, both during and after participation.

Keywords: morbidity, muscularity, psychobehavioral disorders, psychology

Body image disorders such as anorexia nervosa (AN) and bulimia nervosa (BN) have been well documented in the clinical literature.1,2 Societal pressures ranging from media advertisement campaigns to sports icons often dictate the way an “ideal” body should look. For several decades, much of the focus on body image disorders has centered on women. In American society, the feminine ideal is to appear thin. Males, however, are encouraged to be muscular and “ripped.” We have witnessed a gradual shift in how males perceive their bodies3,4 and a growing trend toward a condition called reverse anorexia or bigorexia. Dysmorphia or dysmorphism is defined as an anatomical malformation.5 As attention grows in this area of psychopathology, the clinically appropriate term of muscle dysmorphia (MDM) has come into usage. In cases of reverse anorexia, bigorexia, or muscle dysmorphia, the primary focus is not on how thin a person can get but rather on how large and muscular.3,6–9 The perceived “malformation” is a lack of size or strength. Unfortunately, despite the growing attention, in comparison with AN and BN, few interventional strategies have been explored.3

Much like females participating in sports that stress thinness, such as cross-country running, gymnastics, or dance, males with MDM are typically involved in sports stressing size and strength such as football, wrestling, or competitive bodybuilding.3,6–8,10 Muscle dysmorphia is not limited to the sporting world. As society bombards people at younger ages with images of what the “ideal” body looks like, MDM will likely continue to increase in the general population. One example, from a popular bodybuilding magazine11 released in November of 2000 included advertisements with headlines such as, “Ashamed of your unwanted hair growth?” “Stop hair loss now!” and “Get fast results,” in addition to promotions for liposuction and breast implants in men. Mixed messages linking physical fitness with body image insecurities are being sent to America's youth.

Body image dissatisfaction has been a concern throughout the ages.2,3,9,12,13 During medieval times, in efforts to appear more masculine and muscular, men would stuff their shirts with hay or don bulky armor.3 Whether for survival and intimidation or aesthetics, body dissatisfaction and its sequelae pose a growing social problem.

As athletic trainers, we work in venues in which strength, speed, size, and power are typically valued and encouraged. Although the exact causes are unknown, participation in athletics can be a “gateway” to MDM.3 Others argue that those with predispositions to MDM may be more apt to participate in sports.

Our purpose is to inform and educate the practicing athletic trainer and educator about the proposed causes of MDM, how to identify it, and how to intervene appropriately.

WHAT IS MUSCLE DYSMORPHIA?

Muscle dysmorphia is a form of obsessive-compulsive disorder that is more specifically subcategorized as body dysmorphic disorder. When they hear the term obsessive-compulsive, many people conjure images of excessive hand washing or bizarre daily rituals. When applied to the framework of body image, the obsession becomes the body or, more specifically, the level of muscularity and leanness. The compulsion is to achieve the desired levels of muscularity and leanness.3

Body Dysmorphic Disorder

Body dysmorphic disorder is recognized as a psychopathologic condition in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM IV-TR).5 This disorder is often seen as a subcategory of obsessive-compulsive disorder with more specific criteria. Dissatisfaction with anything related to the human body is possible, ranging from baldness to skin appearance.5,14–17 Perceived flaws in the patient's body are often unappreciated by others but are very real to the person experiencing them. Focus on the flaw is so preoccupying that people often become depressed and obsessed and may even lose relationships or jobs as a result.3,5,12,14,16,17 Pope et al3 noted, “Body dysmorphic disorder is often confused with vanity; this is not the case as most people don't want to look great, they just want to look acceptable.”3 For expanded definitions of these disorders, see Table 1.

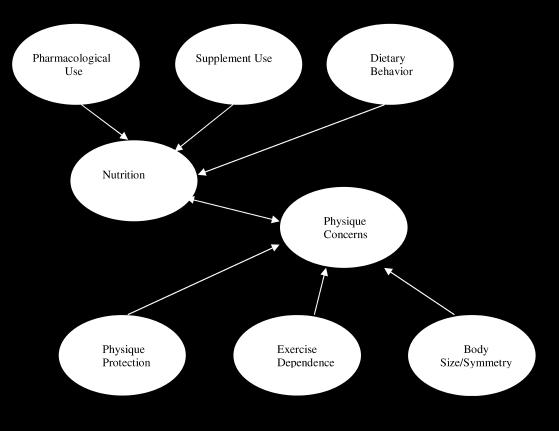

Table 1. Diagnostic Criteria for Body Dysmorphic Disorder and Muscle Dysmorphic Disorder.

Muscle Dysmorphia

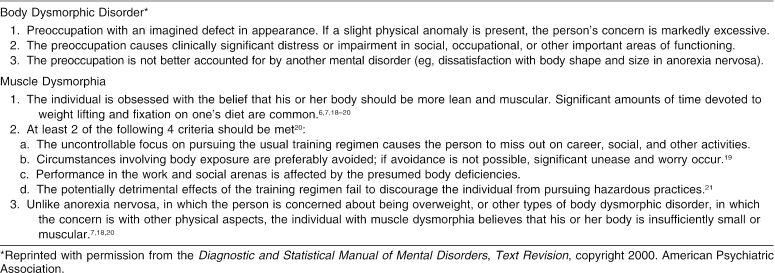

Formally defined, MDM is a pathologic preoccupation with muscularity and leanness. A subcategory of body dysmorphic disorder, MDM involves a specific dissatisfaction with muscularity rather than the body as a whole,10,18,19 with a discrepancy between the imagined and actual self.3,7,8,10,18–24 In one of the first papers addressing MDM, Pope et al10 defined MDM, explained symptoms and epidemiology, and proposed diagnostic criteria. Individuals obsess about being inadequately muscular and lean when, in fact, they are not. With MDM, compulsions may include spending endless hours in the gym or countless amounts of money on supplements; deviant eating patterns; or even substance abuse.3,7,8,10,18–22,25 Lantz et al23 diagrammed factors postulated to contribute to the psychobehavioral attributes of MDM (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Contributing psychobehavioral factors for muscle dysmorphia. (Copyright 2004. From Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research; by Lantz CD, Rhea DJ, Cornelius AE. Reprinted by permission of Alliance Communications Group, a division of Allen Press, Inc).

WHO DOES MUSCLE DYSMORPHIA AFFECT?

Muscle dysmorphia can affect anyone, but it is more prevalent in males than in females.3,8,10,18 Although numbers are difficult to estimate, as many as 100 000 people or more worldwide meet the formal diagnostic criteria in the general population.3 Prevalence among athletes has yet to be ascertained through formal clinical studies, with much of the data having been extrapolated from general population numbers. As social influences change and encourage a more muscular physique, children at progressively younger ages are at increased risk for developing body image disorders such as MDM.6 In one study,3 adolescent boys were presented with various body types generated on a laptop computer. Each was asked to select a body type based on 3 questions: (1) What would you like your body to look like? (2) What do you think the ideal male body should look like? and (3) What do you think others think your body looks like? The subjects were presented with various body types and asked to select the one that most closely resembled their own. On the first 2 questions, the boys selected body types that were 30 to 40 pounds heavier than the reference image, whereas answers to the third question revealed that they perceived their bodies to be much thinner and weaker looking than they actually were. Some boys even asked if they could make the largest image bigger. These disturbing findings, which have since been supported by other authors,3,6,25,26 illustrate how changing ideals of body image can distort perceptions at younger ages.6,27

This phenomenon is not isolated to the United States; similar results were obtained in Europe and South Africa.24,25,28–30 With body image so closely related to self-esteem and self-confidence, society may be setting the stage for a generation of boys and girls who are dissatisfied with their bodies, not because they are unattractive, but because society tells them they have to look better.2-4,6,9,12,21,25,14-17,26-28,31

Data describing the effect of MDM on females are also very limited. However, researchers acknowledge that females can be affected by MDM, although the drive for muscularity is less than that seen in males.32

SIGNS AND RECOGNITION

Attributing MDM to a single causative factor is difficult, if not short-sighted. Some attribute this disorder to the effect of the media and popular culture,3,6,12,21,25,28 whereas others lean toward individual psychological predisposing factors.1–3,6,9 Phillips and Drummond,12 for example, stated, “current Western culture promotes standards of beauty and success that focus on physical attractiveness and leanness.” Authors in the area of body image dissatisfaction have noted how marketing campaigns once targeting only female body image insecurities are now aimed at males as well.6,20,25,26,28,33 Whatever the causes, MDM is a growing concern, particularly in terms of identifying persons who are most susceptible to its development.3,7,23 Clinical case studies suggest that MDM is most often found in persons who are dissatisfied with their bodies and are heavily involved in weightlifting and other muscle development activities. Because the term “weightlifter” can be applied to most anyone, a clear definition of how MDM relates to the overall concept of “fitness” is still vague.23

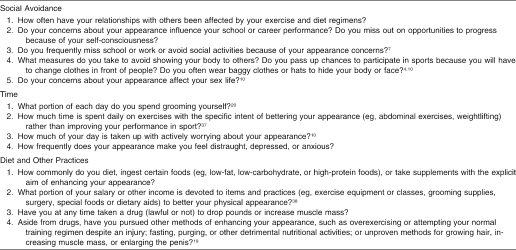

To assess the presence of MDM, certain questions can be asked (Table 2).3 There is no particular number of questions used to affirm MDM, nor is there a specific time to ask them; the questions simply serve as a guide to the clinician to connect the pieces of the MDM puzzle. The athletic trainer must ascertain the scope of the situation and select applicable questions.

Table 2. Questions the Athletic Trainer Can Ask to Determine Whether Muscle Dysmorphia is Present3,8.

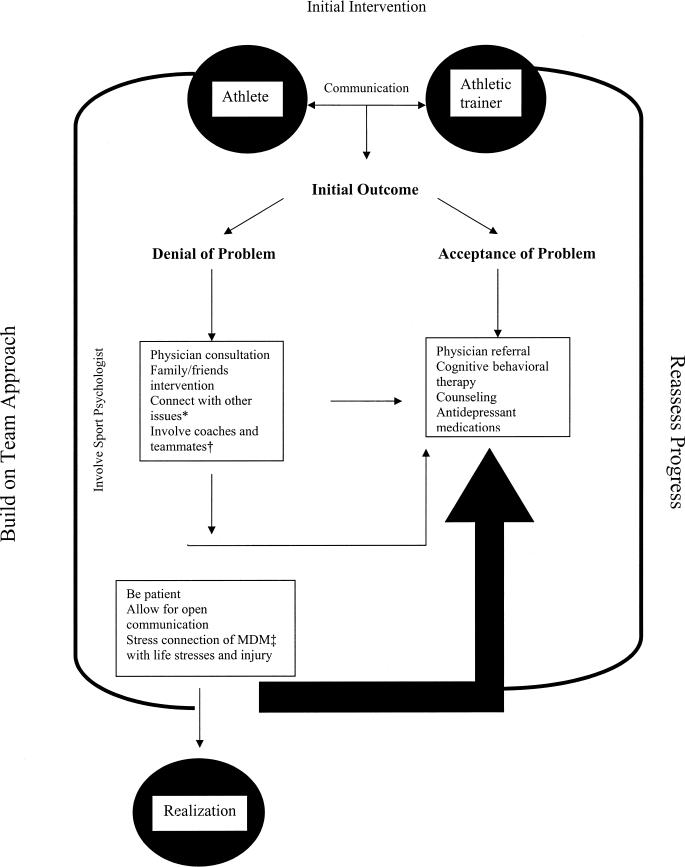

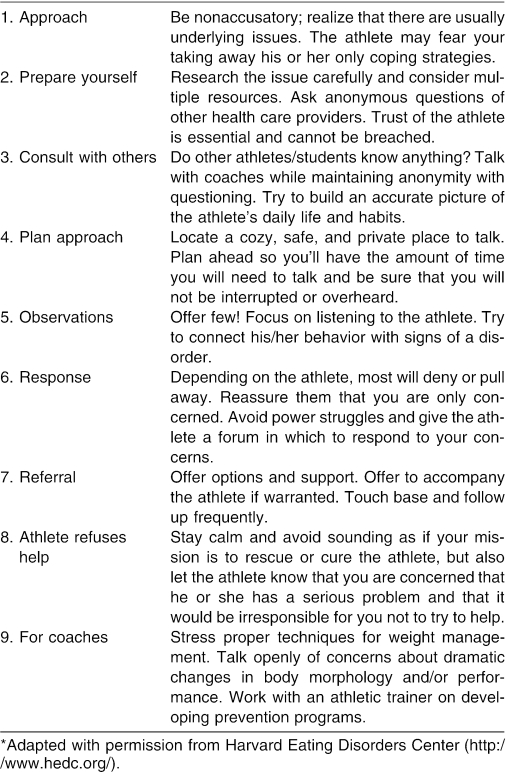

Questioning athletes presenting with MDM-consistent signs follows the methods used for intervening with AN and BN. The athlete should be approached in a nonconfrontational manner, and concern for his or her well-being should be the major motivation for the intervention. A private setting (ie, outside the athletic training room), such as a private office or other predetermined location, should be used to maintain athlete confidentiality. All 13 questions should be asked of the athlete, and the athletic trainer should note how the athlete's answers to each question connect to other noticeable traits, such as workout routines, eating habits, and supplement usage. As when the athletic trainer approaches an athlete with possible AN or BN, the questioning serves as a point of confirmation while other signs and symptoms related to the disorder are investigated. If the school does not have an established protocol, several models exist to help develop one (see Resources and Suggested Readings). A flow chart for referral (Figure 2) is an excellent first step. Recognition may not always be clear-cut in the world of athletics. Often, the disorder is masked by the “demands of the sport.” Coaches and staff expect athletes to be physically fit and muscular. If an athlete has a predisposition to MDM, the sport environment may provide a breeding ground for the disorder. As with other diseases and disorders, many signs and symptoms exist on the disorder continuum. One obvious sign is excessive staring in mirrors.3,5,7,8,10,14,18–22 Some individuals stare in a mirror to process aesthetic values and to evaluate overall physical prowess,3,21 whereas others fear that they are “wasting away.”3,19,21,25 Although mortality rates are not high for MDM,7 several notable morbidities are associated, ranging from lifestyle issues, such as spending excessive time in the gym and ignoring social commitments, to others that affect physical health, such as androgenic-anabolic steroid use.3,4,6-8,10,18-22,25,33,34

Figure 2. Conceptual model for developing an intervention strategy to aid a person with possible muscle dysmorphia or another related body image disorder. *Such as loss of a job, poor athletic performance, relationship problems, or physical harm (ie, substance abuse, injuries, etc). †MDM indicates muscle dysmorphia; ‡, if deemed appropriate.

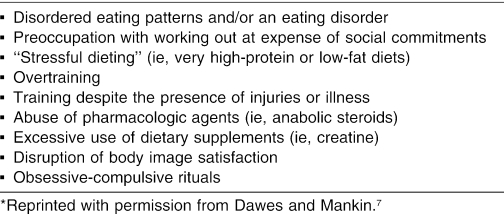

Muscle dysmorphia can have a profound effect on all aspects of life, often interfering with normal daily function.7 For example, one man with MDM detailed how he missed the birth of his first child because he had to finish his 6-hour workout. Another testified that he lost his prestigious position at a well-known law firm because he had to adhere to a strict dieting and eating regimen.3 Other self-destructive behaviors associated with MDM are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Self-Destructive Behaviors Associated with Muscle Dysmorphia*.

MUSCLE DYSMORPHIA AND SUBSTANCE ABUSE

Androgenic-Anabolic Steroids

Many people who are unable to achieve personal goals or handle pressures from coaches regarding an unrealistic ideal body image may turn to anabolic steroids or other dangerous substances to satisfy their aspirations.3 Certainly not everyone at risk for developing MDM will resort to anabolic steroid use, but all such people may be at risk for suffering devastating damage to their self-esteem and physical and emotional well-being.3,8 Many with MDM or similar symptoms resort to prolific usage of sports and nutritional supplements.34,35 Companies producing and selling these products prey on males' and females' insecurities about their bodies.3 Many individuals take higher doses of these products than recommended, which may predispose them to a variety of health concerns, such as renal failure.3,6–8,21,35,36 Pope et al3 noted that “as people at risk for MDM grow increasingly familiar with the weightlifting and bodybuilder subculture, they will inevitably learn through this subculture that anabolic steroids can deliver in a way that no supplement can.”

Athletics alone can provide enough motivation for a person to start using dangerous doses of supplements, anabolic steroids, or both. Athletes with a poor sense of self and body image dissatisfaction can and do fall prey to substance abuse very easily.13,18,21,25,34,35

IMPLICATIONS FOR ATHLETIC TRAINING

As a whole, athletes are very concerned with their health and well-being. In some sports, appropriate weight and physique are qualities that may improve some aspects of athletic performance. The notion of becoming larger to gain an “edge” over the competition permeates sports today.37 Athletes involved in sports stressing muscularity, leanness, and aesthetics may be predisposed to developing MDM. For both male and female athletes, body weight is another concern. Dissatisfaction with body weight can lead to body dysmorphic disorder or, more specifically, MDM.1–3 Overall, athletes are more critical of their bodies and body weights than are recreational exercisers or nonexercisers.2,13 Failure to meet performance standards or expectations may lead to a negative view of the body, resulting in a greater emphasis on achieving a certain look or body ideal. This combination of sport performance, body image, and body weight can result in a body image disorder such as MDM.

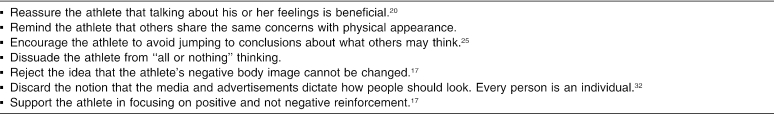

As clinicians, we must be well versed in many areas. The well-being of our athletes needs to be approached in a holistic manner that includes both the somatic body and the psyche. The better informed athletic trainers are about recognizing body image disorders such as AN, BN, disordered eating patterns, body dysmorphic disorder, and muscle dysmorphia, the better the treatment options we can offer. When questioning an athlete suspected of having a body image disorder such as MDM, the athletic trainer should take a similar approach to that used with AN or BN. The Harvard Eating Disorders Center says, “A student may deny the problem, be furious that you discovered their secret, and feel threatened by your caring. Athletes in particular may feel frightened that their participation in sports will be threatened by your concern. Give them time and breathing space once you have raised your concerns.”38 A listing of the Center's suggestions for helping students is available in Table 4.

Table 4. Useful Techniques for the Athletic Trainer Treating an Athlete with Muscle Dysmorphia3.

Assessment and referral protocols should be individualized to the institution where they will be applied. Accusations must take a backseat, and the athlete should be approached with the utmost respect, understanding, and empathy in order for an intervention to work. Other approaches include being sensitive to the condition, nonjudgmental, and empathetic, but also realistic and forthright.3

TREATMENT OPTIONS

To understand treatment options for MDM, it is important to first address common barriers. Many with MDM do not seek treatment3; thus, the onus is on the health care professional to identify and intervene at the right time, just as in AN and BN.1,3,7 The biggest hurdle is convincing the person with MDM that he or she needs help. Many approaches can help the person recognize the condition, such as openly discussing body image, encouraging group or team discussion, and soliciting the help of coaching and support staff to address the topic. The difference between AN and MDM is that people with AN may be forced to seek treatment because of associated morbidity, whereas people with MDM usually present in good health, at least in the short term. The devastating psychological and social consequences often go unrecognized and, thus, untreated.7

Currently, no specific programs have been developed to help people with MDM, although several general approaches have made headway. Those who have responded best have been treated with antidepressant medications such as fluoxetine (Prozac; Eli Lilly and Co, Indianapolis, IN), alone or in combination with cognitive behavioral therapy.3 Many people who have milder forms of MDM are not the best candidates for the aforementioned therapies, because they may seek intervention only when they have a related injury or illness. Reaching those who suffer from the effects of MDM but do not outwardly present with frank signs and symptoms is a problem. As with many athletic-related conditions and injuries, athletic trainers are on the front lines and need to be well versed in recognizing the signs and symptoms of MDM, with prevention serving as the ultimate goal. Athletic trainers can recognize lesser forms of MDM by simply being familiar with the dispositions of their athletes as well as with the common signs and symptoms of MDM.

To properly address MDM, society has to undergo a paradigm shift in how we approach our bodies and body images. Traditionally, males are not supposed to be concerned with looks or vanity, let alone talk about them. Social mores of forced silence add fuel to a building internal fire.3 Males, particularly boys, do not want to be viewed as feminine or weak.3,6

In helping people with MDM, several steps need to be considered. The individual with MDM has a distortion of his or her own reality. Nothing is ever good enough, even though the person may believe that one more cycle of steroids or one more cosmetic procedure is all that will be needed in order to look good. This process feeds into itself, perpetuating the psychological need for more.3,4,9,12,13

Encouraging talking about inner feelings and dispelling feelings of isolation are good first steps. Discussing the social aspects of the disorder with the person can also be useful. For specific questions, refer to Table 5.

Table 5. Helping Students With Body Image Disorders*.

THE ATHLETIC TRAINER'S ROLE

Athletic trainers can use several resources to approach the issue of MDM (see Tables 2–4). Resources, however, are only beneficial when those using them are properly educated. The impetus for this review is to serve that purpose: to heighten the health care professional's awareness and knowledge regarding the subject matter. Many schools have policies on handling and discussing eating disorders such as AN and BN.1,14,26 Athletic trainers should encourage their schools to adopt and implement similar approaches to MDM.

When considering programming to address MDM and other body image disorders, athletic trainers need not reinvent the wheel. Programs most likely exist to address AN and BN, so further programming and education can be added to encompass all athletes and all ranges of sports. Developing informational pamphlets and offering group discussions, team meetings, and occasional educational in-service programs can heighten the athletes' and coaches' awareness of the disorder. Most of these approaches can be developed in house, incurring minimal expenses. Programming can be as creative or as basic as suits the needs of the school and its athletes. For a comprehensive listing of very useful resources, please consult the Resources and Suggested Readings section of this paper.

CONCLUSIONS

Our goal in writing this article was to raise athletic trainers' awareness of the psychobehavioral condition known as MDM. The intent is not to pathologize working out, bodybuilding, or fitness. Pope et al3 noted, “If you wash your hands 5 times per day, that's healthy, if you wash your hands 200 times per day, you very likely have a problem.” Nearly 20 years of research have yielded some basic recommendations for combating MDM. Pope et al3 promoted a fundamental cultural change in the way people view their bodies. Health care professionals have to be able to recognize the signs and symptoms of MDM, select the right type of intervention, and maintain contact with the affected person through follow-up. Helping people to resist the lure of media and advertisements is a fundamental step.3,7 Many of the supermodels (both females and males) we see in everyday life are products of airbrushing or body image drugs such as anabolic steroids.25,28,34,35 Certain industries' livelihoods come from making people feel insecure about their bodies, whether it is telling females that they need to look thinner or males that they need to be more muscular. Athletic trainers need to reinforce the concept that how one looks on the outside does not define the type of person one is, one's athletic ability, or the quality of one's character. We should draw on our forefathers' wisdom that it is all right to look ordinary.3 Wanting to look good and feel healthy are positive traits, but it is not healthy to compare oneself to the unattainable standards imposed by Western society. If we allow ourselves and our athletes to be taken in by these cultural beliefs about beauty, the process of muscle MDM and related morbidity will self-perpetuate. Raising awareness among athletic trainers and health care professionals will help in addressing this growing public health concern.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank John E. Massie, PhD, LAT, ATC; Jodi Johnson, MS, ATC; and Robert Colandreo, DPT, LAT, ATC, CSCS, for revising and editing this manuscript. Gratitude is also extended to Harrison G. Pope Jr, MD, MPH, for his brilliant insight on the topic and conceptualization of this manuscript.

RESOURCES AND SUGGESTED READINGS

Books

Pope HG Jr, Phillips KA, Olivardia R. The Adonis Complex: The Secret Crisis of Male Body Obsession. New York, NY: The Free Press; 2000.

Phillips KA. The Broken Mirror: Understanding and Treating Body Dysmorphic Disorder. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 1996.

Web Sites

Butler Hospital Body Image Program. http://www.butler.org/bdd.html

Harvard Eating Disorders Center. http://www.hedc.org/

Information on body image: http://www.headdocs.com

Legal aspects of body image disorders: http://www.aldenandassoc.com/articles/eating_disorders.htm

Organizations

The Body Image Program (Butler Hospital/Brown University)

Contact: Dr. Katherine Phillips, (401) 455-6466 or Katherine_Phillips@brown.edu

Body Image Program

Butler Hospital

345 Blackstone Boulevard

Providence, RI 02906

The Obsessive Compulsive Foundation, Inc (203) 315-2190

PO Box 9573

New Haven, CT 06535

REFERENCES

- Pope HG, Jr, Katz DL, Hudson JI. Anorexia nervosa and “reverse anorexia” among 108 male bodybuilders. Comp Psychiatry. 1993;34:406–409. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(93)90066-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imm PS, Pruitt J. Body shape satisfaction in female exercisers and nonexercisers. Women Health. 1991;17:87–96. doi: 10.1300/j013v17n04_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG, Jr, Phillips KA, Olivardia R. The Adonis Complex: The Secret Crisis of Male Body Obsession. New York, NY: The Free Press; 2000.

- Mangweth B, Hausmann A, Walch T. Body fat perception in eating-disordered men. Int J Eat Disord. 2004;35:102–108. doi: 10.1002/eat.10230. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM IV-TR) 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

- Cohane GH, Pope HG., Jr. Body image in boys: a review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 2001;29:373–379. doi: 10.1002/eat.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawes J, Mankin T. Muscle dysmorphia. Strength Cond J. 2004;26:24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Chung B. Muscle dysmorphia: a critical review of the proposed criteria. Perspect Biol Med. 2001;44:565–574. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2001.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiggemann M. Body-size dissatisfaction: individual differences in age and gender, and relationship with self-esteem. Pers Individ Dif. 1992;13:39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG, Jr, Gruber AJ, Choi PYL, Olivardia R, Phillips KA. Muscle dysmorphia: an underrecognized form of body dysmorphic disorder. Psychosomatics. 1997;38:548–557. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(97)71400-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flex. November 2000.

- Phillips JM, Drummond MJ. An investigation into body image perception, body satisfaction and exercise expectation of male fitness leaders: implications for professional practice. Leisure Stud. 2001;20:95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Davis C, Cowels M. Body image and exercise: a study of relationships and comparisons between physically active men and women. Sex Roles. 1995;25:33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KA. Body dysmorphic disorder: the distress of imagined ugliness. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1138–1149. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.9.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veale D, Kinderman P, Riley S, Lambros C. Self-discrepancy in body dysmorphic disorder. Br J Clin Psychol. 2003;42:157–169. doi: 10.1348/014466503321903571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippopoulos GS. The analysis of a case of dysmorfophobia. Can J Psychiatry. 1979;24:379–401. doi: 10.1177/070674377902400504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter JR, Sun AM. In pursuit of perfection: a primary care physician's guide to body dysmorphic disorder. Am Fam Physician. 1999;60:1738–1742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouri EM, Pope HG, Jr, Katz DL, Oliva P. Fat-free mass index in users and nonusers of anabolic-androgenic steroids. Clin J Sport Med. 1995;5:223–228. doi: 10.1097/00042752-199510000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivardia R. Mirror, mirror on the wall, who's the largest of them all? The features and phenomenology of muscle dysmorphia. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2001;9:254–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivardia R, Pope HG, Jr, Hudson JI. Muscle dysmorphia in male weight lifters: a case-control study. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1291–1296. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.8.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorpette G. You see brawny; I see scrawny. Sci Am. 1998;278:24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Choi PYL, Pope HG, Jr, Olivardia R. Muscle dysmorphia: a new syndrome in weightlifters. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36:375–377. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.36.5.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz CD, Rhea DJ, Cornelius AE. Muscle dysmorphia in elite-level power lifters and bodybuilders: a test of differences within a conceptual model. J Strength Cond Res. 2002;16:649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitzeroth V, Wessels C, Zungu-Dirwayi N, Oosthuizen P, Stein DJ. Muscle dysmorphia: a South African sample. Psych Clin Neurosci. 2001;55:521–523. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2001.00899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangweth B, Pope HG, Jr, Kemmler G. Body image and psychopathology in male body builders. Psychother Psychosom. 2001;70:38–43. doi: 10.1159/000056223. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leit RA, Pope HG, Jr, Gray JJ. Cultural expectations of muscularity in men: the evolution of Playgirl centerfolds. Int J Eat Disord. 2001;29:90–93. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(200101)29:1<90::aid-eat15>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG, Jr, Olivardia R, Gruber AJ, Borowiecki JJ. Evolving ideals of male body image as seen through action toys. Int J Eat Disord. 1999;26:65–72. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199907)26:1<65::aid-eat8>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG, Jr, Olivardia R, Borowiecki JJ, 3rd, Cohane GH. The growing commercial value of the male body: a longitudinal survey of advertising in women's magazines. Psychother Psychosom. 2001;70:189–192. doi: 10.1159/000056252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski JP, Pope HG., Jr. Body ideals in young Samoan men: a comparison with men in North America. Int J Mens Health. 2002;1:163–171. [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG, Jr, Gruber AJ, Mangweth B. Body image perception among men in three countries. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1297–1301. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.8.1297. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J, Foley E. Body image: stability and sensitivity of body satisfaction and body size estimation. Int J Eat Disord. 1988;8:55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber AJ, Pope HG., Jr. Compulsive weight lifting and anabolic drug abuse among women rape victims. Comp Psychiatry. 1999;40:273–277. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(99)90127-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG, Jr, Katz DL. Bodybuilder's psychosis. Lancet. 1987;1:863. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91642-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanayama G, Gruber AJ, Pope HG, Jr, Borowiecki JJ, Hudson JI. Over-the-counter drug use in gymnasiums: an underrecognized substance abuse problem? Psychother Psychsom. 2001;70:137–140. doi: 10.1159/000056238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanayama G, Pope HG, Jr, Hudson JI. “Body image” drugs: a growing psychosomatic problem. Psychother Psychosom. 2001;70:61–65. doi: 10.1159/000056228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewnowski A, Yee DK. Men and body image: are men satisfied with their body weight? Psychosom Med. 1987;49:626–634. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198711000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams MH. The Ergogenic Edge: Pushing the Limits of Sports Performance. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1998:123–127.

- Harvard Eating Disorders Center. Approaching a student. Available at: www.hedc.org. Accessed July 25, 2004.