Abstract

Objective: To present the case of an elite female volleyball player who complained of diarrhea and fatigue after preseason training.

Background: The athlete lost 8.1 kg during the first 20 days of training, and we initially suspected an eating disorder. The sports medicine team interviewed the athlete and found she did not have psychological symptoms indicative of an eating disorder. The results of routine blood tests revealed critically high platelet counts; in conjunction with the physical findings, the athlete was referred to a gastroenterologist.

Differential Diagnosis: Our initial suggestion was an eating disorder. Therefore, the differential diagnosis included anorexia athletica, anorexia nervosa, and bulimia nervosa. On referral, the differential diagnosis was anemia, gastrointestinal dysfunction, lymphoma, or bowel adenocarcinoma. Diarrhea, weight loss, and blood test results were suggestive of active celiac disease, and a duodenal biopsy specimen confirmed this diagnosis.

Treatment: The athlete was treated with a gluten-free diet, which excludes wheat, barley, and rye. Dietary substitutions were incorporated to maintain adequate caloric intake.

Uniqueness: The presence of active celiac disease may not be uncommon. However, elite athletes who face celiac disease present a new challenge for the athletic trainer. The athletic trainer can help guide the athlete in coping with the lifestyle changes associated with a gluten-free diet.

Conclusions: One in every 200 to 400 individuals has celiac disease; many of these individuals are asymptomatic and, therefore, their conditions are undiagnosed. Undiagnosed, untreated celiac disease and patients who fail to follow the gluten-free diet increase the risk of further problems.

Keywords: gluten-sensitive enteropathy, celiac sprue, gluten-free diet

Celiac disease affects as many as 1 in every 200 to 400 individuals in North America and Europe.1,2 We suggest that the frequency of celiac disease in the general population is mirrored in the athlete population. As a result, athletic trainers should become aware of the signs and symptoms, referral practices, and treatment of celiac disease to best care for patients. The following is a case report of a female collegiate volleyball player with the uncomfortable and performance-inhibiting symptoms of celiac disease and the successful diagnosis and treatment of her condition.

CASE REPORT

History

A National Collegiate Athletics Association Division I female volleyball player (height, 183 cm; weight, 81 kg) presented with symptoms suggestive of the early stages of an eating disorder, which were exacerbated by a significant increase in preseason conditioning. The athlete was observed throughout her athletic participation and during team meals to identify abnormal behaviors. An eating disorder was suspected based on a rapid decrease in body mass, loss of appetite, diarrhea, and vomiting after meals. The athlete was removed from volleyball activity soon after her condition began to affect not only her performance but also activities of daily living. In addition to fatigue at team practices and during team meals, the athlete struggled with fatigue while attending class and began deferring social engagements. Additionally, the volleyball coaches observed a decline in her athletic performance. To identify disordered eating behavior, the coaching and sports medicine staff monitored her behaviors before, during, and after practices, competitions, team meals, and during team travel. The athlete was observed falling asleep at meals, in the team van or bus, and before and during practices in which she was not participating.

Initial Referral

After an intensive interview process, the sports medicine team determined that the athlete did not have clinically relevant psychological symptoms of an eating disorder, such as compulsion for excellence or poor self-image. However, the athlete had lost a considerable amount of body mass during the first 20 days of the season (8.1 kg), prompting the sports medicine staff to refer her to the university health center for a physical examination and laboratory testing. On initial referral, the athlete's physical examination revealed a body mass of 72.9 kg with 14.5% body fat, with other relevant findings of diarrhea, fatigue, bloating, and abdominal pain. The results of routine blood testing identified clinical abnormalities within her complete blood cell count. Table 1 provides the athlete's blood test results 9 months before symptoms appeared and after symptoms progressed. Testing revealed low values for hemoglobin, hematocrit, mean corpuscular volume, mean corpuscular hemoglobin, and red blood cell distribution width and an increased platelet count. Laboratory findings combined with relevant findings from the physical examination warranted further investigation and referral to a gastroenterologist.

Table 1. Complete Blood Count Results 9 Months Before and at Time of Diagnosis.

Differential Diagnosis

The blood test results suggested an anemic state, but the low values for hemoglobin, hematocrit, mean corpuscular volume, mean corpuscular hemoglobin, and red blood cell distribution width had not changed from previous testing, and her current condition could not be attributed to these findings. The increased platelet count suggested the possibility of cancer or blood disease and required further testing. Therefore, the initial differential diagnosis included an eating disorder but then on further investigation was expanded to include anemia, gastrointestinal dysfunction, lymphoma, or bowel adenocarcinoma.

Gastroenterologist Referral

The gastroenterologist inferred that the diarrhea, weight loss, and laboratory findings were indicative of active or symptomatic celiac disease. To confirm the diagnosis, the specialist ordered a biopsy of the distal duodenum and serologic testing. The biopsy specimen revealed diffuse loss of villi, crypt hyperplasia, increased inflammatory cells in the lamina propria, and intraepithelial lymphocytes. Loss of villi (Figures 1 and 2) decreases the surface area for absorption of nutrients, leading to malabsorption. Crypt hyperplasia generally represents insidious increases in cellular formation and indicates a cancerous tumor, but in this volleyball player, no cancer was found. The presence of inflammatory cells and lymphocytes indicated an active immune system response.4,5 Serologic testing revealed elevated antigliadin and endomysial antibody levels, which suggested an active immune system response. In addition, malabsorption had led to noticeable vitamin K and B12 deficiencies. Diarrhea, weight loss, abnormal blood test results, anemia, abnormal biopsy results, and elevated serum antibody levels all contributed to the definitive diagnosis of symptomatic celiac disease.

Figure 1. Small bowel biopsy displaying normal mucosal folds with presence of villi and no inflammation within the lamina propria. Adapted with permission from Freeman.3.

Figure 2. Small bowel biopsy displaying villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, and inflammatory cells in the lamina propria. Adapted with permission from Freeman.3.

Case Evolution and Treatment

The patient was prescribed a gluten-free diet (GFD), which excludes all wheat-based products, and nutritional counseling. Symptoms subsided with these immediate alterations to her diet. The athlete was unable to return to volleyball practice immediately, but as she gained command of her diet to meet the demands of her daily activities and her athletic participation, she returned to play. As the GFD was implemented, the athlete completed her sophomore season and continues to participate without limitation. Her coaches and teammates reported that her athletic performance improved and even exceeded that of her pre-illness status.

DISCUSSION

Characteristics of Celiac Disease

Celiac disease, also known as gluten-sensitive enteropathy and celiac sprue, is a gastrointestinal condition that affects the small intestine. The small intestine is divided into 3 sections. The duodenum is the C-shaped region located just distal to the stomach. The jejunum and the ileum create the extensive coiling of the small intestine, moving proximally to distally from the duodenum.6 Celiac disease causes chronic inflammation of the villi, or fingerlike projections that aid in nutrient absorption6 within the mucosal lining of the jejunum in the small intestine.4 Specific characteristics of celiac disease include a mosaic pattern and scalloped folds in the lining of the small intestine, best identified with endoscopy. These mucosal characteristics, as well as pallor and erythema with visible blood vessels within the lumen of the small intestine, are the best indicators for diagnosing celiac disease. The sensitivity for diagnosis using these findings ranges widely from 50% to 95%.7 Recent and relevant literature reveals that histologic changes within the intestine may vary.7 With celiac disease, the histologic changes in the small intestine are attributed to a hypersensitivity to gluten, a protein found in wheat, barley, and rye grains.1,8

Celiac disease is relatively common, and various factors appear to contribute to its development. The disease is labeled “silent” or subclinical, because cases often differ greatly among individuals, and the condition may go undiagnosed for years because the patient does not exhibit or report any signs or symptoms of the disease.1 The signs and symptoms of celiac disease typically include diarrhea, steatorrhea (fatty stool), excess flatus (gastrointestinal gas), bloating, abdominal pain, weight loss, menstrual irregularities, fatigue, and weakness.2

In North American and European populations, celiac disease occurs in 1 in 200 to 400 individuals;1,2 however, many individuals' conditions remain subclinical and fail to come to the attention of health care providers. Some investigators believe latent celiac disease is triggered by a life-altering event or extreme stress.5 These events or life stressors may vary from the death of a close family relative or friend to the academic stress faced by collegiate student-athletes or preprofessionals. Cultural and environmental factors may also play a role in the incidence and course of celiac disease. The onset of the disease has been linked to geographic location (varying amounts of wheat-based products within diets among continents and cultures), and the pattern and duration of breast feeding can delay the onset of symptoms.1

Diagnosing celiac disease can be difficult, and it is important to recognize risk factors for concomitant conditions. The primary risk factors for celiac disease are heredity, Down syndrome, and cultural influences.1,2,9 Ten percent of first-degree family members tend to pass celiac disease to their offspring.1 Commonly associated conditions include unexplained anemia, type 1 diabetes mellitus, dermatitis herpetiformis, arthralgia, unexplained osteoporosis, thyroid disease, infertility, epilepsy, and unexplained neurologic disease.9 Anemia is strongly associated with the occurrence of celiac disease; half of patients with newly diagnosed celiac disease also have anemia.5 Dermatitis herpetiformis, a skin reaction with pruritic lesions similar to those of herpes simplex,5 is commonly diagnosed as atypical psoriasis or nonspecific dermatitis and occurs in 10% of patients with celiac disease.1,5,10 These indicators can encourage clinicians to initiate further evaluation and diagnostic testing, resulting in serologic testing and endoscopic biopsies for definitive diagnosis.

Diagnostic Tools

Distal duodenal biopsy is considered the gold standard to recognize and diagnose the histologic changes associated with active celiac disease.1,5,7,9,11 The purpose of the biopsy is to identify atrophied villi and cellular changes within the lumen of the small intestine. Endoscopic viewing assists the physician by allowing visualization of the distal duodenum during the biopsy and identification of the mucosa texture. Serologic testing detects antibodies associated with celiac disease and is a useful screening procedure to identify at-risk patients.5,9 The antibodies associated with celiac disease include the IgA antiendomysial antibody (85% to 100% sensitive, 96% to 100% specific) and the IgA antitransglutaminase antibody (95% sensitive, 90% specific).5

Treatment

Treatment options for individuals diagnosed as having celiac disease primarily include dietary changes with adjunctive pharmacologic intervention. A GFD is the most commonly prescribed treatment.2 It consists of substituting potatoes, rice, and corn-based products for wheat, barley, and rye in the diet in amounts sufficient to provide appropriate caloric levels for the athlete's energy expenditure. The key to a healthy GFD is identifying all gluten-rich foods, which can be difficult, especially during dining-out experiences.2 Because effective treatment depends on maintenance of the GFD, guidance from a qualified nutritionist may assist the athlete in gaining the appropriate knowledge about these lifelong dietetic alterations. Consumption of gluten may cause relapse to symptomatic celiac disease.1 Eliminating gluten from the diet can be beneficial within 3 to 6 days, but full histologic restoration of the small intestine will not occur for approximately 6 months.2

Untreated, symptomatic celiac disease can lead to serious subsequent conditions.1,5,9,12 Calcium and vitamin D deficiencies are related to the malabsorption of nutrients. Osteoporosis can develop if a patient or a physician does not recognize the signs of celiac disease. In patients with concomitant dermatitis herpetiformis, chances of developing cancers such as lymphoma and bowel adenocarcinoma may increase. When the implementation of a GFD is delayed or when celiac disease is untreated, symptoms will persist and can be potentially fatal as malabsorption continues. In the case of unsuccessful treatment, the use of corticosteroid drugs may be indicated; however, these drugs are not used in those responding to the GFD.1

Clinical Implications

The signs and symptoms of celiac disease are often confused with other conditions, and without appropriate diagnostic testing, definitive diagnosis is difficult. The symptoms that result from the disease may mislead clinicians in their diagnosis toward anemia, Crohn's disease, and food allergies. As in our patient, the outward signs of celiac disease, especially in an elite female athlete, may suggest an eating disorder. Sundgot-Borgen13 found that athletes were 10% more likely than the average population (3.2%) to participate in disordered eating, and 20% of women were even more likely to have disordered eating than their male counterparts. Disordered eating is often related to an increased incidence of restrained eating, frequent weight training, and overtraining. With the increased incidence and risk of an elite female athlete developing an eating disorder, the early signs of her disease, and the early psychosocial pattern of behavior, the differential diagnosis included anorexia athletica, anorexia nervosa, and bulimia.

Because this student-athlete began preseason with increased pressure by her coach, her teammates, and herself to improve her skills, the athletic training staff continued to believe there were desires to increase fitness and performance beyond normal expectations. Rumors of ergogenic aid use existed before the athlete reported for her sophomore season preparticipation examination, but we were unable to validate them, because the athlete was not supplementing at the time of blood testing. We suggest that the expectations to perform at an elite level and the academic and social pressures of a college student may have increased the stress level of our athlete. In response to these stressors, combined with the outward signs of weight loss, vomiting, and diarrhea, an eating disorder was suspected as an escape from the pressure and an attempt to improve performance to meet these expectations. However, in this volleyball player, rather than the suspected eating disorder, the increased life stress triggered the adult onset of celiac disease.

Dietary Challenges of Athletes With Celiac Disease

Many demands are placed on today's collegiate athlete. Stresses imposed by full or partial scholarships, academics, social life, physical demands of the sport, and the challenges of living away from home affect every aspect of the collegiate athlete's daily life. Daily stresses place an even greater emphasis on nutrition and dietary concerns; however, only 32% of young athletic adults (22 to 29 years old) have reported they are nutritionally conscious and make healthy selections in their diet choices.14 According to the American Academy of Sports Medicine, the American Dietetics Association, and the Dieticians of Canada,15 at times of high-intensity exercise, energy intake must meet or exceed energy output. A low-energy diet can cause fatigue, loss of muscle mass, menstrual irregularities, loss of bone density, and increased risk of injury or illness.

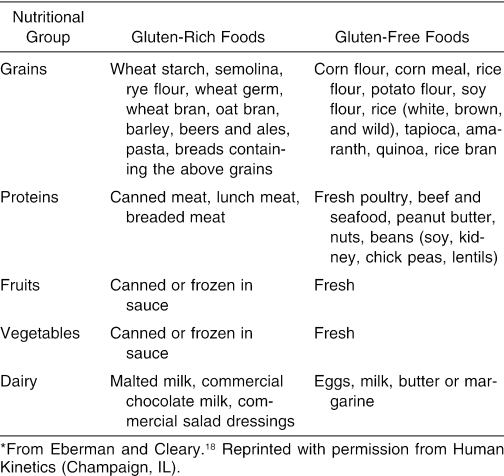

Compared with nonathletes, female athletes tend to take energy primarily from carbohydrates and less so from lipid sources.16 Carbohydrates are an important source of energy, especially during exercise. The recommended intake of carbohydrates is 6 to 10 g/kg of body weight, but energy output, sport, sex, and climate can affect these recommendations.15 Breads, pasta, cereal, rice, and fruit are the common diet choices linked to carbohydrates, but those diagnosed as having celiac disease are unable to eat these wheat-based items. Several simple alternatives include vegetables, milk, and yogurt.17 Table 2 reflects appropriate gluten-free dieting, providing common carbohydrate sources and their gluten-free alternatives. A GFD becomes slightly more complicated and eliminates the ingestion of wheat, barley, and rye, all of which are carbohydrate-rich and gluten-rich sources. Typical carbohydrate substitutions within a GFD are rice, corn, flax, quinoa, tapioca, potato, amaranth, nuts, and beans.5 The challenge of a GFD for the average person is significant, and most dietitians recommend at least 4 consultations with a nutritionist.2 The most important consultation involves identifying commonly consumed gluten-containing foods within the patient's diet and finding suitable alternatives. Patients must maintain the GFD for their entire life to avoid recurrence or exacerbation of the disease.

Table 2. Suggested Alternatives to Gluten-Rich Foods*.

Effective treatment of celiac disease in an elite athlete depends on a successful transition to a GFD while sustaining a high-energy output. Optimal athletic performance reflects dedication and self-control while maintaining a GFD and continuing to provide the body with sufficient carbohydrate alternatives for energy.

Uniqueness of Our Case

Certified athletic trainers and other health care professionals should be aware that the occurrence of celiac disease is higher than once thought. Clearly, the potential exists for athletes to have celiac disease and for its signs and symptoms to be confused with other conditions. In our case, we were initially unable to identify the signs of celiac disease because we suspected a possible eating disorder. This case of celiac disease was unique because of the presentation and the role the certified athletic trainers played in tailoring the treatment to meet the athlete's needs. Daily adaptations were necessary, and the recommendations made by the physician, the nutritionist, and the certified athletic trainer aided in the athlete's return to elite athletic activity. Referral is indicated when the athlete's care extends beyond the playing field and when the athlete's activities of daily living are affected by the signs and symptoms. Guidance in a life-changing treatment is required and should come directly from those health care professionals closely associated with the athlete's daily care. Certified athletic trainers are the health care professionals closest to the athlete and, because of this relationship, we are ideal and educated counselors to our athletes.

Footnotes

Lindsey E. Eberman, MS, LAT, ATC, contributed to conception and design; analysis and interpretation of the data; and drafting and final approval of the article. Michelle A. Cleary, PhD, LAT, ATC, contributed to conception and design and critical revision and final approval of the article.

Address correspondence to Lindsey E. Eberman, MS, LAT, ATC, College of Education, Department of Health, Physical Education, and Recreation, Florida International University, Miami, FL 33199. Address e-mail to ebermanl@yahoo.com.

REFERENCES

- Branski D, Troncone R. Celiac disease: a reappraisal. J Pediatr. 1998;133:181–187. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inman-Felton AE. Overview of gluten-sensitive enteropathy (celiac sprue) J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99:352–362. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman H. Celiac disease: a review. B C Med J. 2001;43:390–395. [Google Scholar]

- Pugh M. Stedman's Medical Dictionary. 27th ed. ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000:511,756,963,1694.

- Nelsen DA., Jr. Gluten-sensitive enteropathy (celiac disease): more common than you think. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66:2259–2266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marieb EN, Mallatt J, Wilhelm PB. Human Anatomy. 4th ed. San Francisco, CA: Pearson Education Inc; 2005:628.

- Chitti LD, Cummins AG, Roberts-Thompson IC. Gastrointestinal: celiac disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:1417. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2001.02642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardlaw G. Perspectives in Nutrition. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill Co; 1999:208.

- Edwards M. Living with coeliac disease: treatment for gluten sensitivity can seem like a life-sentence. Practice Nurse. 2003;25:24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Farhadi A, Banan A, Fields J, Keshavarzian A. Intestinal barrier: an interface between health and disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:479–497. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2003.03032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollid L. Molecular basis of celiac disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:53–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storsrud S, Hulthen L, Lenner R. Beneficial effects of oats in the gluten-free diet of adults with special reference to nutrient status, symptoms and subjective experiences. Br J Nutr. 2003;90:101–107. doi: 10.1079/bjn2003872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundgot-Borgen J. Weight and eating disorders in elite athletes. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2002;12:259–260. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2002.2e276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark N. Nutrition support programs for young adult athletes. Int J Sport Nutr. 1998;8:416–425. doi: 10.1123/ijsn.8.4.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Sports Medicine, the American Dietetic Association, and Dietitians of Canada. Joint position statement: nutrition and athletic performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:2130–2145. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200012000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cupisti A, D'Alessandro C, Castrogiovanni S, Barale A, Morelli E. Nutrition knowledge and dietary composition in Italian adolescent female athletes and non-athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2002;12:207–219. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.12.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinci DM. Effective nutrition support programs for college athletes. Int J Sport Nutr. 1998;8:308–320. doi: 10.1123/ijsn.8.3.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberman LE, Cleary MA. Celiac disease and athletes. Athl Ther Today. 2004;9(6):46–47. [Google Scholar]