Abstract

Background: General practitioners (GPs) are widely reported to ‘miss’ half of the psychological problems present in their patients.

Aims: To describe the relationship between frequency of consultations and GP recognition of psychological symptoms.

Design of study: Survey of GPs and their patients.

Setting: General practices in the southern part of New Zealand's North Island.

Methods: Participants were randomly selected GPs (n = 70), and their patients (n = 3414, of whom a sub-set of 386 form the basis of this study). The main measure was the comparison between GP and composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI) recognition of psychological problems.

Results: Of the GPs selected, 90% participated. The CIDI was completed by 70% of selected patients. In patients (n = 386) with a CIDI-diagnosed disorder, 63.7% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 53.3 to 74.1) were considered by the GP to have had psychological symptoms in the last year; 40.1% (CI = 31.0 to 49.2) to have had clinically significant psychological problems, and 33.8% (CI = 24.9 to 42.6) were given an explicit diagnosis. However, in those CIDI-diagnosed patients who had been seen five or more times during the previous year, these recognition figures increased to 80.2% (CI = 68.9 to 91.4), 59.4% (CI = 45.9 to 72.9) and 53.6% (CI = 40.1 to 67.1) respectively, and dropped to 28.8% (CI = 13.0 to 44.7), 13.6% (CI = 3.4 to 23.7), and 10.7% (CI = 1.4 to 19.9) among patients not consulting during the previous year. GPs often differed from the CIDI in their assessment of clinical significance and diagnosis.

Conclusion: GP non-recognition of psychological problems was at a problematic level only among patients with little recent contact with the GP. Efforts to improve GP recognition of mental disorder may be more effective if they target new or infrequent attenders, and encourage patient disclosure of psychological issues.

Keywords: continuity of patient care; diagnosis; interview, psychological; mental disorders

Introduction

GENERAL practitioners (GPs) provide most of the treatment of mental disorder of people in the general population:1 estimates range from about three-fifths in the United States2 to three-quarters in New Zealand.3

Internationally, about one in four patients in primary care has a diagnosable mental disorder.4 Although prevalence of mental disorder in the New Zealand general population is similar to that in most western countries,5,6 in New Zealand primary care more than one patient in three (35.5%, conf-idence interval [CI] = 29.5 to 41.5) has had a diagnosable DSM-IV disorder, such as depression, substance use disorder, or an anxiety disorder, within the previous 12 months.7 Research into GP recognition of psychological problems in their patients has suggested that, internationally, up to half of the people with mental disorders who present in primary care are not recognised,8-11 and argues that this may constrain the optimal delivery of adequate treatment.9,12,13

In 1980 Goldberg and Huxley12 identified ‘patient factors’ and ‘GP factors’ as reasons for the low rate of recognition of mental disorders. Extensive research confirmed the relevance of the presence and severity of comorbid physical illness;14-16 sociodemographic factors;17-20 the nature and severity of symptoms presented;12,14,15 recency of onset of psychological problems;8,21,22 and lack of fit of diagnostic frameworks.12,23,24 There is also evidence of the relevance of GP factors, such as actual or perceived lack of knowledge or skills;25-28 and interest in or attitudes towards mental illness.19,22,29 However, it has also been pointed out that the nature of the primary care system itself is a source of non-recognition of mental disorder.11,30 As GPs often spread diagnostic decisions over several consultations, the GP's prior knowledge of the patient may have a critical bearing upon awareness of psychological problems and clinical decision making. This has been demonstrated in several studies, which have shown that patients who visit their doctor more often are more likely to be recognised as having a psychological problem.1,19,30-33

These studies have not reported extensive analysis of the role of frequency of consultation or discussed the implications of differences in rates of recognition. This study uses data from two sources to describe GP detection of psychological problems in their patients in terms of a hierarchy of three levels of recognition. It then determines the effect of frequency of consultations over the previous year, and considers the implications of the findings for strategies to influence GP recognition.

Method

This article is based upon data from the first phase of a larger study, the MaGPIe study. Detailed methods of this research are described elsewhere.7

HOW THIS FITS IN

What do we know?

Conventional wisdom suggests that general practitioners (GPs) ‘miss’ half the psychological problems present in their patients. Patient care may be compromised by the failure of GPs to recognise common mental disorders, such as depression and anxiety, and substance use disorders.

What does this paper add?

GP non-recognition of psychological problems was at a problematic level among patients with little recent GP contact. Interventions to improve GP recognition may be more effective if they foster continuity of care, focus on the disorders most likely to be missed, take into account high levels of comorbidity of common mental disorders, encourage patient disclosure of psychological issues, and target new or infrequent attenders.

Setting and sampling

Participants comprised 70 randomly selected GPs in the southern part of New Zealand's North Island. General practice in New Zealand is a partially state-subsidised health system, predominantly funded by fee-for-services, financed by a combination of patient payments, tax funding and, less commonly, insurance. Government funding pays for most of the cost of pharmaceutical and laboratory services, with a low level of user charge for such services. GPs act as gatekeepers to secondary and tertiary care, through referrals to hospitals for specialist, including elective, care. New Zealand consultations are typically 12–15 minutes in length, and it is common to be able to see the practitioner of choice within 48 hours.

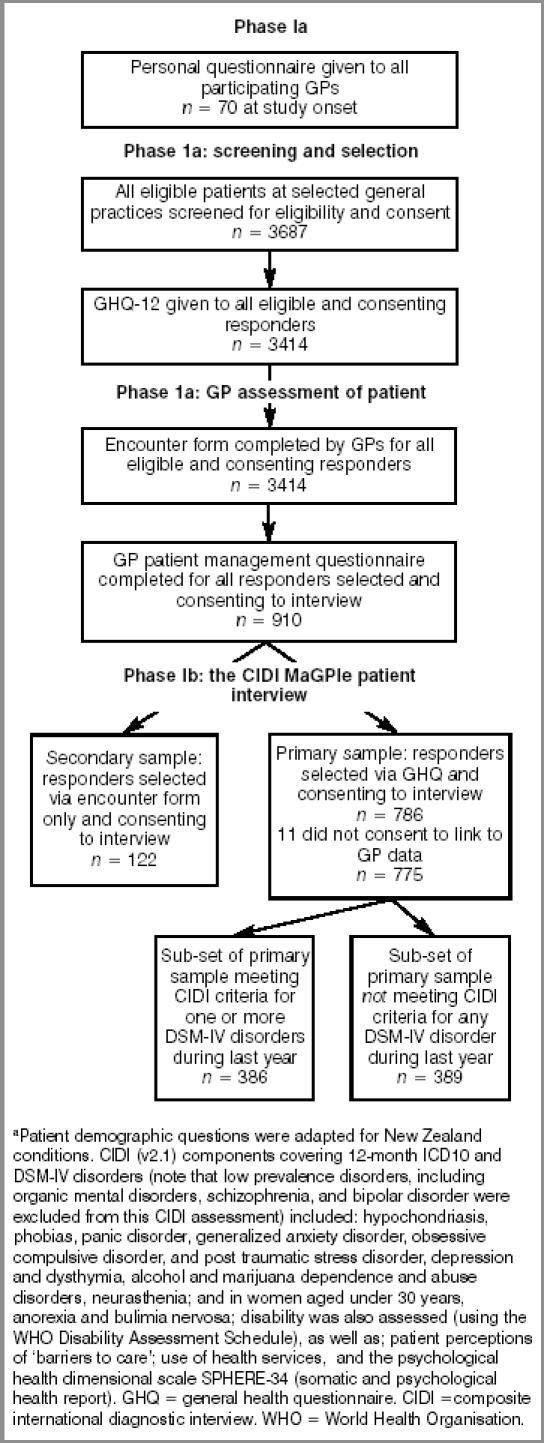

Fifty consecutively attending eligible adult patients were recruited from the practice of each GP. Stratified sampling of these patients identified a primary sample of 1151, of whom 786 were interviewed. Of these, 775 also consented to their GP disclosing information about their health status, and of these, data from 386 who met the criteria for one or more DSM-IV disorders diagnosed by CIDI (composite international diagnostic interview)34 during the previous year form the basis of this article (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Instruments and samples used in phase I of the MaGPIe Study.a

Measures

The measures used were based on the World Health Organisation's (WHO's) collaborative study of psychological problems in general health care.35

Ethical approval

Wellington and Manawatu-Whanganui Ethics Committees approved the methods and procedures used in the study.

Recruitment of GPs and patients

GPs were selected at random from 299 known eligible GPs in two administrative health districts in New Zealand, yielding a mix of urban, small town and rural practices.7 In phase 1a, for recruitment of patients/index consultation, patients were eligible for screening if they were: 18 years old or over; able to read English well enough to understand and complete the GHQ (general health questionnaire)-12 screening instrument;36 and about to consult with the GP for their own health concerns.

On completion of the GHQ, the interviewer used the score to determine if the patient was selected for the primary sample of CIDI interviews. Of those with high GHQ scores of 5 or more, 100% were selected; medium scorers (2 to 4) had a 30% probability of selection; low scorers (0 to 1) had an 8% probability of selection. The doctor completed an ‘encounter’ form that included an assessment of psychological health for every patient aged 18 years or over they saw that day. For each selected and consenting patient the GP completed a more detailed patient management questionnaire, covering the patient's care and treatment over the previous 12 months.

In phase 1b the first MaGPIe patient interviews were carried out, consisting primarily of the CIDI. This was computerised using the WHO's ISHELL software, and was usually carried out in patients' homes within a few days of the index consultation.

Levels of psychological problem recognised by GPs

Levels of psychological problems recognised in the previous 12 months were defined using data from two sources: the GP's encounter form rating of severity of psychological disorder, and the GP's responses to the patient management questionnaire about psychological disorders diagnosed in the previous 12 months. These levels and their definitions are outlined in Box 1.

Box 1. The levels of general practitioner recognition of psychological problems in patients.

| Level | Definition |

|---|---|

| Any psychological symptoms | Any report of psychological symptoms, distress, or disorder whatsoever. |

| Clinically significant psychological problems | Requires identification as a mild, moderate, or severe case of psychological disorder from the encounter form, or reporting any definite psychological disorder on the patient management questionnaire. |

| Explicit psychiatric diagnosis | General practitioner reporting any definite, named disorder on the patient management questionnaire. |

Data scoring and statistical methods

CIDI v2.1 data were scored using WHO algorithms to produce DSM-IV diagnoses. Statistical analyses were carried out using Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) version 8.2. Data were weighted to adjust for differences in probability of being sampled using the method of Kish.37 Weighted prevalence estimates were derived using the SAS procedure SURVEYMEANS, which also adjusted confidence intervals for the effects of clustering within GPs. Relative risks were estimated from weighted means output from Proc SURVEYMEANS, with 95% confidence intervals for relative risks estimated using Taylor's expansion estimate to account for clustering.38

Results

Of the 78 eligible randomly selected GPs approached, 70 agreed to participate. This gave a 89.7% response rate.

GHQ screening questionnaires were completed by 3414 (92.6%) of 3687 eligible general practice attenders. Of the 1334 selected for interview, 357 refused further contact, 27 became ineligible for the more demanding interview (because of limited language skills or worsening illness), 37 were not traceable and 3 were lost through operational error, yielding 910 interviews, of whom 788 were the primary sample (a further two patients were lost: n = 786). Response rate for completion of the initial MaGPIe interview was 70%. This article focuses on the 386 patients from the primary sample for whom the CIDI interview determined that the criteria for one or more DSM-IV disorders were met and who also consented to linking of CIDI data and GP opinion.

Table 1 shows that of those with a CIDI-diagnosed disorder in the last year, almost two-thirds were recognised by their GP as having had psychological symptoms in that year (63.7%, CI = 53.3 to 74.1), less than half were recognised as having had a clinically significant psychological problem (40.1%, CI = 31.0 to 49.2), and just over a third were given an explicit diagnosis of some sort (33.8%, CI = 24.9 to 42.6). GPs more frequently agreed with the CIDI diagnosis of depression than a CIDI diagnosis of anxiety or substance use disorder, and concurred with the CIDI diagnosis in 34.8%, 14.6%, and 7.4% of patients with CIDI depressive, anxiety, and substance use disorders respectively.

Table 1.

Level of psychological problem identified by GPs among patients with a CIDI DSM-IV diagnosis of a common mental disorder in the 12 months before the study.

| Any CIDI disordera | CIDI anxiety disorderb | CIDI depressive disorderc | CIDI substance use disorderd | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of psychological problem identified | %e | 95% CIf | %e | 95% CIf | %e | 95% CIf | %e | 95% CIf |

| No psychological symptoms recognised | 36.3 | 25.9 to 46.7 | 28.6 | 18.0 to 39.2 | 27.0 | 13.6 to 40.4 | 48.8 | 31.9 to 65.6 |

| Any psychological symptoms | 63.7 | 53.3 to 74.1 | 71.4 | 60.8 to 82.0 | 73.0 | 59.6 to 86.4 | 51.2 | 34.4 to 68.1 |

| Clinically significant psychological problems | 40.1 | 31.3 to 49.2 | 50.6 | 40.3 to 60.9 | 49.6 | 37.6 to 61.5 | 36.5 | 20.9 to 52.1 |

| Explicit psychiatric diagnosis | 33.8g | 24.9 to 42.6 | 43.1h | 33.1 to 53.1 | 42.5g | 30.8 to 54.2 | 30.0h | 14.7 to 45.3 |

| Explicit diagnosis that also concurs with CIDI diagnosis | 22.2g | 16.2 to 28.3 | 14.6h | 7.9 to 21.3 | 34.8g | 24.1 to 45.5 | 7.4h | 2.2 to 12.6 |

an = 386

bn = 241

cn = 222

dn = 103

ePercentage within disorder group estimated for the population of general practice patients with each disorder by weighting the sample according to probability of selection

fCIs are adjusted for clustering within GPs

gn = (n - 2) due to incomplete data

hn = (n - 1) due to incomplete data. CIDI = composite international diagnostic interview.

How recognition of mental disorder is defined can be seen in the data on depression. Of 222 patients with a CIDI- diagnosed depressive disorder, over a quarter (27.0%, CI = 13.6 to 40.4), were not recognised at all as having psychological symptoms and over a third (34.8%, CI = 24.1 to 45.5) were explicitly diagnosed with depression or mixed anxiety-depression by a GP. However, the remaining 38.2% were not unrecognised. They are accounted for by: the GP not categorising their psychological issues as clinically significant (23.4%, CI = 13.5 to 33.3); the GP recognising their problems as clinically significant but not ascribing a particular diagnosis (7.1%, CI = 3.5 to 10.6); or the GP making an explicit diagnosis of something other than depression (7.7%, CI = 3.3 to 12.1).

Table 2 shows that among patients with any CIDI diagnosis who had been seen five or more times during the year prior to the index consultation, 80.2% (CI = 68.9 to 91.4) were recognised by the GP as having psychological symptoms. This was more than twice the rate of recognition for patients with a CIDI diagnosis who had not been seen during the year prior to the index consultation (28.8%, CI = 13.0 to 44.7). Nearly 60% (59.4%, CI = 45.9 to 72.9) of this frequently seen CIDI-positive group were considered to have a clinically significant psychological problem, and 53.6% (CI = 40.1 to 67.1) of them were given an explicit diagnosis. However, the GP agreed with the CIDI-derived diagnosis in only 37.0% (CI = 26.0 to 48.0) of these patients.

Table 2.

Level of psychological problem identified by GPs against number of consultations with a patient in the 12 months before the study.

| No consultationsa | Five or more consultationsb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of psychological problem identified | %c | 95% CId | %c | 95% CId |

| No psychological symptoms recognised | 71.2 | 55.3 to 87.0 | 19.8 | 8.6 to 31.1 |

| Any psychological symptoms | 28.8 | 13.0 to 44.7 | 80.2 | 68.9 to 91.4 |

| Clinically significant psychological problems | 13.6 | 3.4 to 23.7 | 59.4 | 45.9 to 72.9 |

| Explicit psychiatric diagnosis | 10.7 | 1.4 to 19.9 | 53.6 | 40.1 to 67.1 |

| Explicit diagnosis that also concurs with CIDI diagnosis | 5.1 | 1.0 to 9.2 | 37.0 | 26.0 to 48.0 |

a(n = 54).

b(n = 161).

cPercentage within disorder group estimated for the population of general practice patients with each disorder by weighting the sample according to probability of selection.

dCIs are adjusted for clustering within GPs.

CIDI = composite international diagnostic interview.

Nonetheless, among patients with a CIDI diagnosis who had not been seen during the year prior to the index consultation, 28.8% (CI = 13.0 to 44.7) were recognised by the GP as having had psychological symptoms. Only 13.6% (CI = 3.4 to 23.7) were considered to have had a clinically significant psychological problem, 10.7% (CI = 1.4 to 19.9) were given a diagnosis of some sort, and the GP made the same diagnosis as the CIDI for only 5.1% (CI = 1.0 to 9.2) of these patients (Table 2).

Discussion

Summary of main findings

The widely repeated assertion that GPs ‘miss’ 50% of common psychological disorders is an oversimplification. GPs in this study identified psychological symptoms in 63.7% (95% CI = 53.3 to 74.1) of patients with an independently CIDI-assessed mental disorder. Among those seen five or more times in the previous year, 80.2% (95% CI = 68.9 to 91.4) were recognised by the GP as having psychological symptoms, but among patients not seen in the previous 12 months, only 28.8% (CI = 13.0 to 44.7) were recognised. The relationship between frequency of consultation and degree of recognition was consistent in direction and magnitude across all levels of psychological problems identified, from simply recognising the presence of symptoms to making an explicit diagnosis concurring with the CIDI.

GP recognition of psychological symptoms in people with a CIDI-diagnosed disorder also varied according to the type of disorder. Whereas GPs identified psychological symptoms in over 70% of patients with either a CIDI-diagnosed anxiety or depressive disorder, only half of the patients with a CIDI-diagnosed substance use disorder were recognised.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The high response rate among randomly selected GPs, combined with the adequate patient response rate, gives some assurance of generalisability of these findings, and the internationally validated measures of mental disorder enable comparison with other research. However, although the CIDI interview is one marker of significant psychological problems, it is far from an ideal ‘gold standard’.39,40 It is written and designed for non-clinician interviewers, so very high agreement with a clinician would not be expected. Not all those disorders identified by the CIDI but not by the GP were necessarily ‘unrecognised’. Patients may choose not to disclose symptoms to their GP. GPs may choose to not recognise symptoms that are disclosed (for insurance or other purposes). They may think that available diagnostic labels lack relevance in primary care, or may not yet be ready to make a diagnosis. The GP may also have more complete and accurate information than elicited by a standardised interview. The power of the study to detect differences is limited by the sample size, and this is reflected in wide confidence intervals for some comparisons.

Implications for clinical practice and future research

Within a clinical context where continuity of care is a cornerstone,41 and there are competing demands such as acute medical presentations to deal with,31 knowledge of the patient's psychological functioning may accumulate over serial consultations. The amount of improvement in patient outcome possibly achieved by improving recognition is constrained by recognition rates that are already quite high. Therefore, the use of a strategy such as systematic screening of patients for psychological problems should be considered only with the knowledge of patterns of frequency of attending specific to a practice, and following analysis of the gains that might be possible for that practitioner.

Throughout the western world, substantial efforts have been put into approaches that rely heavily upon educating GPs about common mental disorders, especially depression,42-44 although simple educational strategies and passive dissemination of information have been shown to have a minimal effect on healthcare delivery.45 The lack of impact is perhaps not surprising, since effective learning is more likely to occur when it addresses needs in the learner that are accurately identified by both teacher and learner,46 but this is unlikely to be achieved if the idea that ‘GPs fail to identify half the psychological problems present in their patients’15,16 is a key assumption underpinning the educational approach.

Interventions to improve patient outcomes by addressing GP recognition of mental disorder may be more effective if they foster continuity of care, focus on the disorders most likely to be missed, take into account high levels of comorbidity of common mental disorders, encourage patient disclosure of psychological issues, and target new or infrequent attenders.

Acknowledgments

The Health Research Council of New Zealand funded this project (grant 99/065). Supplementary funds were also contributed by the Alcohol Advisory Council (ALAC). We are grateful for the support of the participating GPs and other practice staff, the patients who participated, and our research staff. The ‘MaGPIe’ research group consists of John Bushnell, Deborah McLeod, Anthony Dowell, Clare Salmond, Stella Ramage, Sunny Collings, Pete Ellis, Marjan Kljakovic, and Lynn McBain.

References

- 1.Shepherd M, Cooper B, Brown A. Psychiatric illness in general practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Regier DA, Goldberg ID, Taube CA. The de facto US mental health services system: a public health perspective. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35:685–693. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770300027002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hornblow AR, Bushnell JA, Wells JE, et al. Christchurch Psychiatric Epidemiology Study: use of mental health services. N Z Med J. 1990;103:415–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldberg D, LeCrubier Y. Form and frequency of mental disorders across centres. In: Ustun TB, Sartorius N, editors. Mental illness in general health care: an international study. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons Ltd; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wells JE, Bushnell JA, Hornblow AR, et al. Christchurch Psychiatric Epidemiology Study, part I. Methodology and lifetime prevalence for specific psychiatric disorders. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 1989;23:315–326. doi: 10.3109/00048678909068289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Regier D, Boyd J, Burke J, et al. One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States. Based on five Epidemiologic Catchment Area sites. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:977–986. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800350011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MaGPIe Research Group. N Z Med J. 1171. Vol. 116. 2003. The nature and prevalence of psychological problems in New Zealand primary health care: a report on the Mental Health and General Practice Investigation (MaGPIe) p. U379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tiemens BG, Ormel J, Simon G. Occurrence, recognition and outcome of psychological disorders in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:636–644. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.5.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ormel J, Koeter MW, van den Brink RH, et al. Recognition, management and course of anxiety and depression in general practice. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:700–706. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810320024004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tylee A, Freeling P. The recognition, diagnosis and acknowledgement of depressive disorders by general practitioners. In: Herbst K, Paykel, editors. Depression: an integrative approach. Oxford: Heinemann; 1989. pp. 216–231. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blacker CV, Clare AW. Depressive disorder in primary care. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:737–751. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldberg D, Huxley P. Mental illness in the community: the pathway to psychiatric care. London: Tavistock Publications Ltd; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pignone MP, Gaynes BN, Rushton JL, et al. Screening for depression in adults: a summary of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:765–776. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-10-200205210-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwenk TL, Coyne JC, Fechner-Bates S. Differences between detected and undetected patients in primary care and depressed psychiatric patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1996;18:407–415. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(96)00062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tylee A, Freeling P, Kerry S. Why do general practitioners recognize major depression in one woman patient and yet miss it in another? Br J Gen Pract. 1993;43:327–330. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freeling P, Rao B, Paykel E, et al. Unrecognised depression in general practice. BMJ. 1985;290:1880–1883. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hankin JR, Kessler LG, Goldberg ID, et al. A longitudinal study of offset in the use of non-psychiatric services following specialized mental health care. Med Care. 1983;21:1099–1110. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198311000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoeper EW, Nycz GR, Kessler L, et al. The usefulness of screening for mental illness. Lancet. 1984;i(8367):33–35. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)90192-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marks JN, Goldberg DP, Hillier VF. Determinants of the ability of general practitioners to detect psychiatric illness. Psychol Med. 1979;9:337–353. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700030853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chancellor A, Mant A, Andrews G. The general practitioner's identification and management of emotional disorders. Aust Fam Physician. 1977;6:1137–1143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ormel J, Van Den Brink W, Koeter MW, et al. Recognition, management and outcome of psychological disorders in primary care: a naturalistic follow-up study. Psychol Med. 1990;20:909–923. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700036606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilmink FW, Ormel J, Giel R, et al. General practitioners' characteristics and the assessment of psychiatric illness. J Psychiatr Res. 1989;23:135–149. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(89)90004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barret JE, Barret JA, Oxman TE, et al. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:1100–1106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360048007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Von Korff M, Shapiro S, Burke J, et al. Anxiety and depression in a primary care clinic. Comparison of Diagnostic Interview Schedule, General Health Questionnaire, and practitioner assessments. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:152–156. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800140058008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gask L, Goldberg D, Lessar A, et al. Improving the psychiatric skills of general practitioners: an evaluation of a group training course. Med Educ. 1988;22:132–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1988.tb00423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whewell P, Gore V, Leach C. Training general practitioners to improve their recognition of emotional disturbance in the consultation. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1988;38:259–262. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldberg D, Steele JJ, Smith C. Training family doctors to recognise psychiatric illness with increased accuracy. Lancet. 1980;ii:521–523. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)91843-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldberg D, Steele JJ, Smith C. Teaching psychiatric interviewing skills to family doctors. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1980;62:41–47. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldberg D, Steele J, Johnson A, et al. Ability of primary care physicians to make accurate ratings of psychiatric symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39:829–833. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290070059011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klinkman MS. Competing demands in psychosocial care. A model for the identification and treatment of depressive disorders in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1997;19:98–111. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(96)00145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenberg E, Lussier MT, Beaudoin C, et al. Determinants of the diagnosis of psychological problems by primary care physicians in patients with normal GHQ-28 scores. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2002;24:322–327. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(02)00197-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hankin J, Locke BZ. Extent of depressive symptomatology among patients seeking care in a prepaid group practice. Psychol Med. 1983;13:121–129. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700050121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Locke B, Krantz G, Kramer M. Psychiatric need and demand in a prepaid group practice. Am J Public Health. 1966;56:895–904. doi: 10.2105/ajph.56.6.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robins LN, Wing J, Wittchen HU, et al. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview: an epidemiologic instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:1069–1077. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360017003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Üstün B, Sartorius N. Mental illness in general health care. An international study. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldberg DP, Gater R, Sartorius N, et al. The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychol Med. 1997;27(1):191–197. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kish L. Survey sampling. New York: Wiley; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kendall MG, Stuart A. The advanced theory of statistics. London: Griffin & Co; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henkel V, Mergl R, Kohnen R, et al. Identifying depression in primary care: a comparison of different methods in a prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2003;326:200–201. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7382.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brugha T, Jenkins R, Taub N, et al. A general population comparison of the composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI) and the schedules for clinical assessment in neuropsychiatry (SCAN) Psychol Med. 2001;31:1001–1013. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pereira Gray D, Evans P, Sweeney K, et al. Towards a theory of continuity of care. J R Soc Med. 2003;96:160–166. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.96.4.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paykel E, Tylee A, Wright A, et al. The Defeat Depression Campaign: psychiatry in the public arena. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(Festschrift supplement):59–65. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.6.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hickie I, Davenport T, Naismith S, et al. SPHERE: a national depression project. SPHERE National Secretariat. Med J Aust. 2001;175(Suppl):S4–S5. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Regier DA, Hirschfeld RM, Goodwin FK, et al. The NIMH Depression Awareness, Recognition, and Treatment Program: structure, aims, and scientific basis. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:1351–1357. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.11.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gilbody S, Whitty P, Grimshaw J, et al. Educational and organizational interventions to improve the management of depression in primary care: a systematic review. JAMA. 2003;289:3145–3151. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramsden P. Learning to teach in higher education. London: Routledge; 1992. [Google Scholar]