Abstract

Phosphorylation and O-GlcNAc modification often induce conformational changes and allow the protein to specifically interact with other proteins. Interplay of phosphorylation and O-GlcNAc modification at the same conserved site may result in the protein undergoing functional switches. We describe that at conserved Ser/Thr residues of human Oct-2, alternative phosphorylation and O-GlcNAc modification (Yin Yang sites) can be predicted by the YinOYang1.2 method. We propose here that alternative phosphorylation and O-GlcNAc modification at Ser191 in the N-terminal region, Ser271 and 274 in the linker region of two POU sub-domains and Thr301 and Ser323 in the POUh subdomain are involved in the differential binding behavior of Oct-2 to the octamer DNA motif. This implies that phosphorylation or O-GlcNAc modification of the same amino acid may result in a different binding capacity of the modified protein. In the C-terminal domain, Ser371, 389 and 394 are additional Yin Yang sites that could be involved in the modulation of Oct-2 binding properties.

INTRODUCTION

Sequence-specific protein–DNA recognition is mediated by families of related structural motifs including the helix–turn–helix (1), helix–loop–helix (2), Zn finger (3), leucine zipper/bZIP (4) and POU (Pit, Oct, Unc) motifs (5). The octamer-binding proteins represent an extended subfamily of POU-motif-containing proteins with related protein sequences and similar DNA-binding specificities. The members of this subfamily (designated Oct-l, Oct-2, Oct-3, etc.) recognize an evolutionarily conserved octanucleotide sequence in the vertebrate promoter and enhancer elements (5′-ATGCAAAT-3′). It has been shown that the Oct-2 gene is expressed as multiple mRNAs that vary in splicing patterns (6), thus generating multiple Oct-2 isoforms.

Oct-2 is a transcription factor expressed in the B lymphocyte lineage and in the developing central nervous system that functions through a number of discrete protein domains. These include a DNA-binding POU homeodomain flanked by two transcriptional activation domains (7). Oct-2 also contains a potential ‘leucine zipper’ domain consisting of four leucines separated each by exactly seven residues. The role of the leucine zipper domain in Oct-2 has not been demonstrated in DNA binding. H1-NMR spectral studies (8) revealed the existence of a bipartite POU domain consisting of two isolated sub-domains, the N-terminal POU-specific (POUs) and the C-terminal variant POU homeodomain (POUh), with a flexible linker portion (8,9). The POU-specific sub-domain is critical for high-affinity, sequence-specific DNA binding, but requires the POU homeodomain for fully efficient DNA binding. On the other hand, the isolated homeodomain is capable of low-affinity DNA binding and specific protein–protein interactions (7,10). In vitro studies have shown that the C-terminal activation domain (a serine-, threonine- and proline-rich sequence) is capable of activating transcription from a distance in a B-cell-specific manner.

Induction of post-translational modifications (PTMs) in transcription factors constitutes a common mechanism to regulate gene expression. One of the most common PTMs in transcription factors is phosphorylation that regulates their activity in response to different extra- and intracellular signals, enabling convergence of different signaling pathways at the same factor. There is sufficient evidence to suggest that phosphorylation changes in the POU-domain modulate the ability of the protein to activate transcription (11). Phosphorylated Oct-2 is indeed more competent to activate transcription than the non-phosphorylated molecule (12).

Linkages in which the sugar is covalently attached to an amino acid containing a hydroxyl group occur in great variety of proteins, not only in regard to the partners in this linkage but also in different anomeric configurations. Every amino acid with a hydroxyl functional group (i.e. Ser, Thr, Tyr, Hyp [hydroxyproline] and Hyl [hydroxylysine]) has been implicated. The common O-glycosidic linkages occurring in glycoproteins are GalNAc-α-Ser/Thr and GlcNAc-β-Ser/Thr. The O-GlcNAc modification has been found to be as dynamic and regulatory as phosphorylation (13–15). Interplay between GlcNAc modification and phosphorylation has been observed in many nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins (13–15). O-GlcNAc modification in transcription factors has been shown to be involved in modulating the function of these proteins (16). Protein functions are determined by their 3D structures and the folded 3D structure is in turn governed by the primary structure, and the PTMs the protein undergoes during synthesis and transport. Defining protein functions in vivo in the cellular and extra cellular environments remains a daunting task due to the presence of innumerable other molecules. However, the phosphorylations and O-GlcNAc modifications taking place during and after protein folding are directly related to the modification potential and not only determined by the primary structure or sequence. These PTMs are dynamic and result in temporary conformational changes that regulate many functions of the protein.

Computer-assisted studies therefore could help in determining protein functions by assessing the modification potentials of a given protein. Computational methods in biological sciences have played a crucial role in understanding genomics, proteomics and defining the contribution of phosphorylation, sulfation and glycosylation in various contexts of functional protein regulation. Several programs based on artificial neural networks have been developed to predict glycosylation and phosphorylation sites in proteins with reliable accuracy (Table 1). In most cases, the prediction accuracy is very high except when the modification potential of a protein could be wrongly assessed because a false negative site had been predicted. For example, a Ser residue may have a very high predicted potential for phosphorylation and a potential for O-GlcNAc slightly lower than the threshold. This may result in a false negative Yin Yang site. In fact, both kinase and OGT may have as good an access to a Ser to phosphorylate it or add a O-GlcNAc moiety so that the Ser in question can be considered a bona fide Yin Yang site. Moreover the presence of certain amino acids around a Ser/Thr affects its glycosylation and phosphorylation and has been shown important for modification.

Table 1.

Percentage accuracy of prediction methods

| S. no. | Prediction methods | Percentage accuracy | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycosylated/phosphorylated (%) | Non-glycosylated/non-phosphorylated (%) | Overall (%) | ||

| 01 | NetNGlyc1.0 | 86 | 61 | 76.50 |

| 02 | NetOGlyc 2.0 | 83 | 90 | 86.50 |

| 03 | DictyoGlyc1.1 | 97 | 97 | 97 |

| 04 | YinOYang1.2 | 72.50 | 79.50 | 76 |

| 05 | NetPhos2.0 | 69 | 96 | 82.50 |

In this paper, we describe potential glycosylation, phosphorylation and their possible interplay sites in various domains of Oct-2 that have been predicted and analyzed, using the different prediction methods available. The possible roles played by these PTMs in proper functioning of the multifunctional Oct-2 protein are analyzed on the basis of potential glycosylation and phosphorylation interplay sites in evolutionarily conserved residues of Oct-2. The conserved phylogenetic motifs and/or residues are known to act as key functional sites (17,18) and the PTMs at conserved residues may act as regulatory sites for certain protein functions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sequence data

The sequence of human Oct-2 has been described by many workers (19,20). The sequence data used for predicting phosphorylation and glycosylation sites for Oct-2 of Homo sapiens were retrieved from the SWISS-PROT (21) sequence database with entry name PO2F2_HUMAN and primary accession number P09086. BLAST search was made using the NCBI database of non-redundant sequences (22). The search was made for all organisms' sequences with expect value set to 10 using blosum62 matrix and low complexity filter selecting nr database. A total of 506 hits were obtained. Of these 506 blast hits the first 13 with highest bits score and zero expect value were all from mammals including that of human, mouse, rat and pig, and all these sequences showed at least 70% identity. These 13 mammalian sequences were multiply aligned using CLUSTALW (23) and from these 13, a total of 5 corresponding to human, mouse, rat, dog and pig sequences were selected. Isoforms of the selected sequences were neglected. Another mammalian sequence from Canis familiaris with a higher bits score was also selected. No Oct-2 hit was found in amphibians. One fragment sequence found in these blast hits from Gallus gallus, named Oct-2, was also selected. Two homologous sequences from catfish named Oct-2α and β with the same expect value and almost same bits score were found. Oct-2α with slightly lower bits score was ignored, whereas Oct-2β was selected for final multiple alignment. A sequence from Drosophila named dOct-2 was also selected as an invertebrate representative to find out its degree of divergence of dOct-2 with human Oct-2. Many homologous sequences to the POU domain family were also ignored from various organisms, so as to minimize the number of sequences to be aligned.

To find out conserved residues in human Oct-2, six sequences from the Blast search were finally selected. Of the six, four from mammals (dog, mouse, rat and pig Oct-2), one from fish (catfish Oct-2β) and one from Drosophila (dOct-2) were selected. The sequence data from dog (Canis familaris) was shortened by removing 630 N-terminal amino acids from a total of 1242. The sequence fragment of Gallus (chicken Oct-2) was not included in the final list of multiple alignments, as it was actually a homeobox region with POU domain-like fragment. All seven sequences (Table 2) were aligned using CLUSTALW (23). First alignment was made only for sequences from mammals and these mammalian sequences were multiply aligned with catfish Oct-2, and then with Drosophila dOct-2, one by one and then for all, to find out the degree of divergence of the different sequences. Phylogenetic trees were calculated using CLUSTALW that uses a distance-based algorithm for calculating phylogenetic divergence.

Table 2.

Different Oct-2 proteins used for multiple alignment

| S. no. | Species | Database | Sequence ID/accession no. | Blast results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-value | Bits score | ||||

| 01 | Homo sapiens | SWISSPROT | PO2F2_HUMAN, P09086 | 0.00 | 695 |

| 02 | Sus scrofa | SWISSPROT | PO2F2_PIG, Q29013 | 0.00 | 678 |

| 03 | Ratus sp. | GenBank | AAA40767.1 | 0.00 | 678 |

| 04 | Mus musculus | SWISSPROT | PO2F2_MOUSE, Q00196 | 0.00 | 639 |

| 05 | Canis familaris | RefSeq | XP_541592 | 1 × 10−143 | 510 |

| 06 | Ictalurus punctatus | EMBL | CAA73199.1 | 1 × 10−111 | 405 |

| 07 | Drosophila melanogaster | SWISSPROT | PDM2_DROM, P31369 | 1 × 10−61 | 237 |

Sequence logos

Sequence logos represent the patterns in aligned sequences. They also describe the consensus sequence and depict the relative frequency of residues and the information content (measured in bits) at every position in a site or sequence. The logo displays both significant residues and subtle sequence patterns (24,25). The Web Logo server at the University of California, Berkeley, (CA) was used to generate sequence logos of different regions of Oct-2.

PTMs prediction methods

Methods used for predicting potential O-linked glycosylation sites include NetOGlyc 2.0, 3.0 (26,27) (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetOGlyc/), that predicts O-glycosylation sites in mucin-type proteins (i.e. for O-GalNAc sites), DictyOGlyc 1.1 (28) (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/DictyOGlyc/) and YinOYang 1.2 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/YinOYang/), that both predict O-GlcNAc sites in eukaryotic proteins. The NetNGlyc 1.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetNGlyc/) was used for predicting N-glycosylation sites. The above-mentioned methods for predicting the glycosylation sites are neural network-based. To predict phosphorylation sites in Oct-2, NetPhos 2.0 (29) (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetPhos/) was used. The latter is also a neural network-based program designed by training the networks with protein phosphorylation data from Phosphobase 2.0.

Neural networks-based prediction methods

Artificial neural networks are based on the concept that a neuron receives multiple inputs and gives a single output based on weights associated with the various outputs (30,31). The networks are trained with information contained in the known protein sequences. The O-glycosylation methods of predictions use back propagation for adjusting the weights to a set threshold value based on surface accessibility of amino acid residues (30). The amino acids are represented in the network by sparse encoding (31). It is an encoding method in which each amino acid is represented as a series of 21 binary digits. This encoding is useful as it ensures that each amino acid is equidistant from any other, so that there is no pre-correlation between amino acids. The evaluation of the performance of the neural networks is an important step in developing the prediction methods and different parameters are used to reach this goal. Parameters used by different O-glycosylation prediction methods have almost the same pattern, with slight differences, as in the case of window size (in terms of number of amino acids) used to train the network, to test their performance and number of hidden layers of neurons. Glycosylation prediction methods evaluate the performance through cross validation using Matthews' correlation coefficient (32).

The evaluation of the network performance is obtained by setting a jury of networks. The number of networks for a jury and sequence window is different in the various O-glycosylation prediction methods. The results obtained from all the networks are sigmoidally arranged and averaged to obtain a value between zero and one. Usually a threshold of 0.5 is used for prediction, which means that a site with an output of more than 0.5 is recognized as having a potential to be glycosylated. Similarly, Netphos 2.0 is also a neural network-based prediction method for assessing the possibility of phosphorylation at serine, threonine and tyrosine. This method was developed by training the neural networks with phosphorylation data from the phosphobase similarly to the method used for training networks for glycosylation prediction.

The sequence context of glycosylated threonines is found to be different from that of serines and the charged residues are disfavored at positions −1 and +3. The method NetOGlyc 2.0 correctly predicts 83% of the glycosylated and 90% of the non-glycosylated serine and threonine residues in independent test sets when the network system is cross validated. YinOYang 1.2 employed the sequence data to train a jury of neural networks on 40 experimentally determined O-GlcNAc acceptor sites for recognizing the sequence context and surface accessibility. The number of non-acceptor serine/threonines was reduced from 1251 to 626. The YinOYang 1.2 method (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/YinOYang/) is efficient in a cross validation test as it correctly identifies 72.5% of the glycosylated sites and 79.5% of the non-glycosylated sites in the test set, verifying the Matthews' correlation coefficient of 0.22 on the original data and 0.84 on the augmented data set. The method has the capability to predict the sites known as Yin Yang sites that can be glycosylated and alternatively phosphorylated. NetPhos 2.0 predicts phosphorylation on the OH- function of serine, threonine or tyrosine residues with a sensitivity range from 69 to 96% (29). The present study concentrates on O-glycosylation of the β-GlcNAc modification, phosphorylation and their interplay.

RESULTS

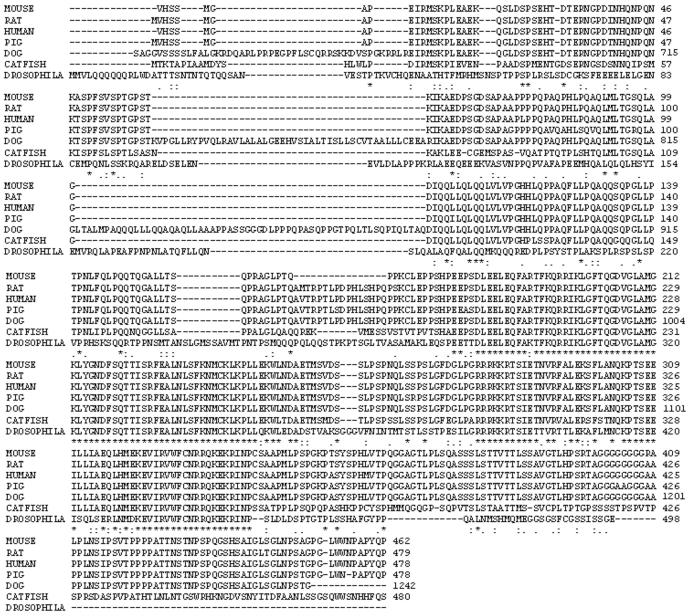

Prediction results of Oct-2 for different O-linked and N-linked glycosylation sites showed that the protein had the potential for both N-linked and O-linked glycosylation. Among O-linked glycosylation sites, O-GalNAc and O-GlcNAc were the most frequent ones. The prediction results for O-GlcNAc modification showed that there were 26 potential sites highly predicted to be modified by O-GlcNAc, 18 on Ser residues, at positions 49, 52, 68, 133, 150, 157, 165, 271, 283, 358, 371, 389, 392, 403, 430, 444, 448 and 452 and 8 on Thr residues at positions 48, 165, 169, 400, 435, 441, 442 and 445 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of potential for O-GlcNAc modification in serine and threonine residues in the human Oct-2 sequence. Green vertical lines show the potential of S/T residues for O-GlcNAc modification and light blue horizontal wavy line shows threshold for modification potential.

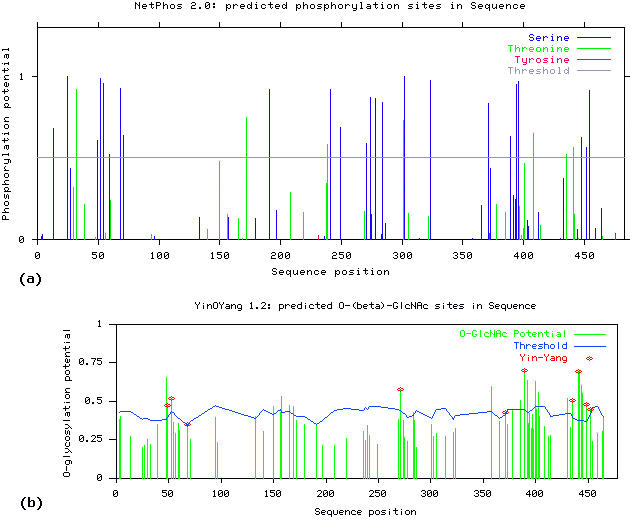

Similarly, the prediction results by Netphos 2.0 for possible phosphorylation sites showed that Oct-2 possesses a high potential for phosphate modification. A total of 31 residues were predicted to be phosphorylated (Figure 2a). These include 24 Ser (at 13, 25, 49, 52, 54, 59, 68, 71, 191, 241, 249, 271, 274, 278, 284, 302, 323, 371, 389, 394, 396, 448, 452 and 454), 7 Thr (at 32, 172, 239, 301, 408, 435 and 441) and 0 Tyr. The elevated number of potential Ser and the very low number of Thr, and no predicted potential Tyr for phosphate modification suggested the possibility that O-GlcNAc modifications in Oct-2 may selectively affect phosphorylation at Ser residues. There were 10 Yin Yang sites according to the prediction results (Ser: 49, 52, 68, 271, 371, 389, 448 and 452; and Thr: 435 and 441), out of which 6 were in the C-terminal region (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

(a) Potential for phosphate modification at serine and threonine residues in the human Oct-2 sequence and (b) sites with potential for both O-GlcNAc and phosphate, the Yin Yang sites with red asterisk at top.

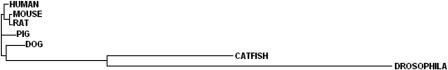

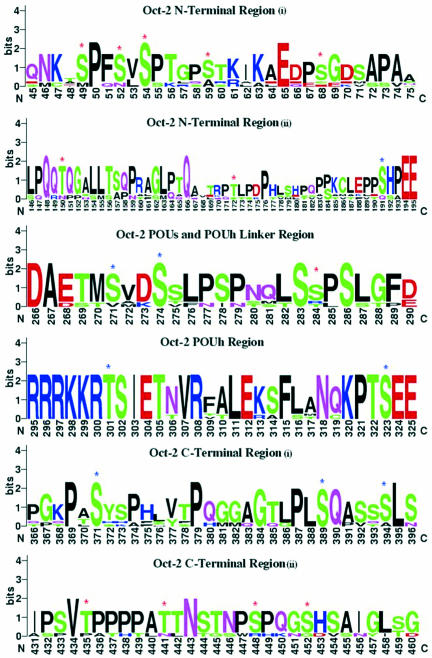

Besides these, there were many other Ser and Thr residues that were predicted to be non-glycosylated, but the phosphorylation potential predicted was either much higher than the threshold or very close to it. Interestingly, such residues were also conserved in all known mammalian Oct-2 and other animal Oct proteins, such as catfish Oct-2 and Drosophila Oct-2 (Figure 3 and Table 3). Thus, such residues which could be considered false negatives may nonetheless act as possible Yin Yang sites other than those predicted by the YinOYang1.2 method (Tables 3 and 4). Table 4 shows all the possible potential Yin Yang sites but among these only eight are most likely to be Yin Yang sites (Table 3). A phylogenetic tree was generated using CLUSTALW (Figure 4). It is a rootless phylogenetic tree showing Drosophila and catfish as an out group. The sequence of dog Oct-2 also became a member of a larger clade with catfish and Drosophila but it possesses more sequence similarity to other mammalian sequences. Polyphyletic mammalian sequences were very similar and monophyletic mouse and rat Oct-2 showed even higher sequence similarity with that of human (Figure 4), suggesting that mammalian and other vertebrate Oct-2 sequences form three distinct diverging phylogenetic categories though their ancestor may be same. Results shown for multiple alignments include catfish and Drosophila to compare the conserved residues of human and mammalian Oct-2 with the more diverging sequences of Drosophila melanogaster dOct-2 (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

Multiple alignments of five mammalian sequences (human, pig, dog, rat and mouse), one from fish (catfish) and one from Drosophila. The consensus sequence is highlighted by asterisk, conserved substitution by double dot and semiconserved substitution by single dot. Different sequences are ordered as in aligned results from CLUSTALW and the numbers in parenthesis show position of human Oct-2 sequence aligned with the others.

Table 3.

Conserved S/T residues with PTMs potential of human Oct-2 aligned with that of other animals

| S. no. | Residue | Conservation status | Modification potential | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mam | Vert | Dros | Phosphate | O-GlcNAc | Yin Yang sites | ||

| 01 | Ser49 | * | * | N | HP | HP | Pr |

| 02 | Ser52 | * | * | . | VHP | HP | Pr |

| 03 | Ser54 | * | * | * | VHP | VCT | FN |

| 04 | Ser59 | * | * | : | HP | VCT | FN |

| 05 | Ser68 | * | N | N | VHP | HP | Pr |

| 06 | Thr150 | * | . | * | VCT | HP | FN |

| 07 | Thr172 | * | DG | . | VHP | VCT | FN |

| 08 | Ser191 | * | * | . | VHP | VCT | FN |

| 09 | Ser271 | * | * | . | HP | HP | Pr |

| 10 | Ser274 | * | * | * | VHP | VCT | FN |

| 11 | Ser284 | * | * | . | VHP | VCT | FN |

| 12 | Thr301 | * | * | * | VHP | VCT | FN |

| 13 | Ser323 | * | * | * | VHP | VCT | FN |

| 14 | Ser371 | * | * | * | VHP | HP | Pr |

| 15 | Ser389 | * | * | DG | HP | VHP | Pr |

| 16 | Ser394 | * | * | : | VHP | VCT | FN |

| 17 | Thr435 | * | . | DG | HP | HP | Pr |

| 18 | Thr441 | * | N | DG | HP | HP | Pr |

| 19 | Ser448 | * | N | DG | HP | HP | Pr |

| 20 | Ser452 | * | N | DG | HP | HP | Pr |

*, Conserved residue; :, conserved substitution; ., semi-conserved substitution; N, non conserved substitution; DG, deletion gap; VHP, very high potential; HP, high potential; VCT, very close to threshold; Pr, predicted by YinOYang 1.1; F.N, false negative; Mam, mammals; Vert, vertebrates; Dros, drosophila.

Note: only those S/T residues are listed in the table which are potential Yin Yang sites and conserved as well. The proposed Yin Yang sites are highlighted by bold face.

Table 4.

Possible Yin Yang sites in different domains of human Oct-2

| S. no. | Domain/region | Yin Yang sites predicted by YinOYang1.2 | Yin Yang sites proposed on the basis of false negative |

|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | N-terminal region | 5 Residues: Ser49, 52, 68 and Thr150, 172) | 3 Residues: Ser54, 59, 191 |

| 02 | POUs POUs domain | Nil | Nil |

| 03 | POUh domain | Nil | 2 Residues: Ser301, 323 |

| 04 | Linker region of POUs & POUh | 1 Residue: Ser271 | 2 Residues: Ser274, 284 |

| 05 | C-terminal region | 6 Residues: Ser371, 389, 435, 441, 448, 452 | 1 Residues: Ser394 |

Figure 4.

The phylogenetic tree generated by CLUSTALW with all sequences for mammalian, catfish and Drosophila Oct-2.

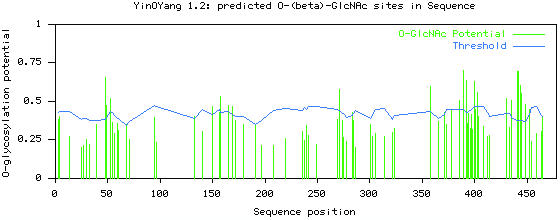

The Web logos of different regions of aligned sequences show that there are many conserved Ser and Thr residues and those with modification potential are marked by blue and red asterisks (Figure 5). Ser/Thr residues with blue asterisk are those with high potential and for which experimental evidence is available, will be considered in detail in the Discussion (Figure 5). Those sites with low modification potential or with no experimental evidence are marked by a red asterisk (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Sequence logos for different aligned regions of Oct-2. The conserved S/T residues with modification potential and with experimental evidence for modification in the region they are located are marked by a blue asterisk on the top of these residues. Whereas other conserved Ser residues are marked by red asterisk, which display either high or low potential as Yin Yang sites but lacking experimental evidence for modification in the region where they are located.

DISCUSSION

Knowledge of the 3D structure is a prerequisite for the full understanding of protein biological functions, as protein–protein recognition events depend on the precise 3D shape of modified and non-modified proteins (33,34). However, a determination of the 3D structure in vivo is extremely difficult, as a given configuration is constantly being modified by intra- and intermolecular interactions occurring between proteins present in body fluids or in the cell.

Most of the structural data available in protein databases have been determined in vitro by X-ray crystallography and/or NMR, but this information is only partially relevant to the dynamic behavior of proteins in vivo. The study of the molecular interactions between multifunctional proteins in vivo is likely to be facilitated by computer-assisted techniques that assess the modification potential of the proteins involved.

The functional classes of transcription activation domains have been described, either acting only when present proximally (glutamine rich domains), or when present at both proximal and distal binding enhancer sites, such as the serine-, threonine- or proline-rich domains (35). Oct-2 possesses two activation domains, one of each functional category, and may influence the expression of targets through different mechanisms, thus acting as multifunctional protein. Mutagenesis studies have shown that both POU sub-domains of Oct-2 are necessary for binding to a DNA site and that the Oct-2 C-terminal domain is involved in its activation (7). Moreover, Oct-2 remains non-functional in the absence of the C-terminal region even if both the POUs and POUh sub-domains are intact (7). Differential activation by Oct-1 and Oct-2 was determined to occur by the combination of multiple activation domains (12) and differential phosphorylation in those activation domains was put forward as a mechanism for Oct-2 activation (12). The members of Oct-2 family are promoter and enhancer recognizing transcription factors. Most transcription factors such as promoter-specific (Sp) transcription factor Sp1 (36) appear to be modified by O-GlcNAc in their transcriptional activation domains (13), suggesting that OGT plays a critical role in the control of protein–protein interactions involved in transcriptional activation.

Direct evidence was provided that O-GlcNAc modification of transcription factors is involved in transcriptional regulation. For instance, O-GlcNAc modification of the glutamine rich Sp1 (SpE) peptide was shown to inhibit its ability to activate transcription (37). The first transcription factor shown to bear the O-GlcNAc modification was Sp1 (36), a ubiquitous transcription factor involved in the control of TATA-less housekeeping gene transcription (38). Homomultimerization is necessary for the synergistic activation of transcription by Sp1 (37), but O-GlcNAc modification of Sp1 in its C-terminal activation domain dramatically decreases its binding to the SpE peptide. This has been proposed to interrupt the hydrophobic interaction of glutamine-rich regions with their partners and abolish homopolymerization (37). Similarly, many transcription factors have been described that are modified by alternative glycosylation and phosphorylation and this interplay was found to regulate key functions of these proteins (13,15,36,37). Flexibility of OGT in recognition of its substrate was described earlier (37). This flexibility in substrate recognition suggested that OGT recognizes conformational features of numerous transcription factors rather than a specific sequence motif, suggesting a rather ubiquitous role of OGT in regulating transcription (37).

During B-lymphocyte maturation, expression of rearranged IgH and IgL genes is critical and is controlled by a complex interaction between regulatory DNA elements and transcription factors (39). Among the regulatory DNA elements necessary for B-cell-specific transcription, the octamer motif is an important transcriptional site that is part of promoters and enhancers of ubiquitously expressed genes.

In contrast to the ubiquitous expression of Oct-1, Oct-2 expression is restricted to B cells and neuronal cells (40). In B cells and neuronal cells, the alternative splicing of Oct-2 generates several proteins (41,42). On the basis of transfection experiments, a critical role for immunoglobulin promoter transactivation was shown for Oct-2 (41). Recent studies (43) demonstrated that in addition to Oct-2, a B-cell-specific cofactor, namely Bob-1, is required. Thus, B-cell specificity of immunoglobulin promoter activity is mediated by the expression of Bob-1 (OCA-B or OBF-1) which associates with the POU domain of the octamer proteins Oct-1 and Oct-2 and alters their recognition specificity (44).

The mechanisms involved in the activation of Oct-2 and its recognition of protein and DNA binding sites are not yet fully understood. The involvement of phosphorylation in the POU domain for DNA binding (11) and that of the C-terminal region for its activation (7,45) have been proposed. Phosphorylation of Oct-2 in vivo has been observed and its involvement in transcription activation documented (7,11,12). Pevzner et al. (11) analyzed the tryptic and chymotryptic phosphorylated Oct-2 peptides and showed that the POU domain-containing peptides were more phosphorylated than any other domain. These authors further defined the possible sites that may undergo phosphorylation. These represent a total of 12 residues, including Ser 25, 27, 191 and Thr 30 and, in the N-terminal region, Ser 197, 208, 271, 274, 275, 278, 314 and 323 residues in the POUs and POUh domains. All these residues are conserved in mammals (Figure 3 and Table 3), but as far as the modification potential is concerned, only Ser 25, 191, 271, 274, 278 and 323 are positive sites for phosphorylation. Similarly, Ser271 is also a positive site for O-GlcNAc modification and a potential Yin Yang site (Figure 2). In addition, Ser191, 274, and 323 and Thr301 show strong potential for phosphorylation and were predicted to be negative sites for O-GlcNAc, although very close to the threshold. Thus, Ser191 in the N-terminal region close to the POUs domain, Ser274 in the linker region of the POUs and POUh sub-domains, and Ser323 and Thr301 in the POUh are false negative Yin Yang sites (Table 3). It is important to note that the Ser191 is conserved in all mammals and catfish, but partly in Drosophila, while Thr301 is conserved in all mammals, vertebrates and Drosophila (Table 3). Similarly, Ser274 and Ser323 are conserved in vertebrates and Drosophila (Figure 3 and Table 3).

Phosphorylation of these residues may result in transient conformational changes by disturbing the non-covalent interactions and leading to down-regulation of expression of the BLR1 gene expression in the mouse, as suggested by Pevzner et al. (11). However, similar results were not found for human lymphoid cells, which might be due to the blocking of phosphorylation sites by O-GlcNAc. From the modification potential and conserved behavior of these residues (Figure 5), we propose that the Ser191, Ser274 and Ser323 are necessarily involved in the differential binding behavior of Oct-2 to the octamer DNA motif. Alternance of phosphorylation and GlcNAc modification at such critical serines may indeed control the function of Oct-2 by influencing interactions of Oct-2 with the DNA octamer motifs.

Recently, Corcoran et al. (7) have suggested the possibility of regulatory phosphorylation in the C-terminal region of Oct-2, stressing the functional importance of this C-terminal region. The signal for the C-terminal domain activation of Oct-2 was proposed to occur through phosphorylation. The potential phosphorylatable residues in that region were serines at positions 365, 389, 392, 393, 394, 396, 403 and 404, and threonines at 397, 400 and 401. These residues are nearly all conserved in mammals, but among these residues, Ser389 had potential for phosphorylation as well as O-GlcNAc modification and was also a predicted Yin Yang site. Ser394, 401 and 403, and Thr408, showed potential for phosphorylation but were negative for GlcNAc modification. Ser394, however, is a false negative potential site for GlcNAc modification, while it has a much higher potential than the required threshold for phosphorylation. Thus, in the C-terminal domain, Ser389 and Ser394 may be the potential Yin Yang sites for regulating the activation of Oct-2 binding through the interplay of the two PTMs (Figure 5).

There are other predicted Yin Yang sites in the Oct-2 N-terminal region, POU domains, linker region and C-terminal region. However, for these sites, no experimental evidence has been obtained until now but even so, the potential of such other residues for modification by phosphate and GlcNAc cannot be ignored. These sites include Ser49, 52, 68 in the N-terminal region, Ser249 in the POUs domain, Ser271 in the linker region of the two POU subdomains and Ser371, 435, 441, 448 and 452 in the C-terminal region (Figure 5). Furthermore, there are other ‘false negative‘ sites that could be considered true Yin Yang sites, as for instance Ser54, 59 and Thr150, 172 in the N-terminal region, Ser284 in the linker region of the two POU subdomains, Thr301 in the POUh sub-domain and Ser394 in the C-terminal region (Figure 5). Among these residues the most important Yin Yang site in C-terminal region seems to be Ser371, which is predicted by the YinOYang 1.2 method (Figure 2), as well as one of the conserved residues in all mammalian Oct-2 and a conserved or semi-conserved substitution in other species (Figure 5). The possibility of Ser371 as potential Yin Yang site is strengthened by the fact that it has Pro at −2 and +3 position, a configuration that favors O-linked glycosylation (46).

Significance of different amino acid residues around glycosylation sites has been described (46). Proline, Ser, Thr and Ala are highly preferred around glycosylated Ser/Thr (46). Calculations based on deviation parameter analysis also showed that among these residues Pro at −3, −1, +1, +2, +3 and +5 positions is highly preferred around glycosylated Ser/Thr (46). Valine at −1 position has been described to be preferred around glycosylated Ser/Thr. Previously, it was described (47,48) that amino acids with small side chain are important in the vicinity of glycosylation site of Ser/Thr, for example Gly at −2 and +2 position was described to be associated with higher degree of glycosylation. Similarly, conserved Pro at +1 position was described to favor phosphorylation (49). Figure 5 shows that most of the proposed Yin Yang sites (Table 3) on Ser/Thr have Pro, Val, Ser, Thr or Gly in their vicinity. Conserved Pro is closely located to nearly all the proposed Ser/Thr interplay sites, and in some cases conserved Val, Gly, Ser or Thr are also present (Figure 5) in the vicinity of these Yin Yang sites.

On the basis of our prediction results and available experimental data, we propose that interplay of phosphorylation and GlcNAc modification at Ser and Thr residues in the C-terminal region of various domains of the Oct-2 transcription factor is apparent. This suggests that interplay sites can play an important role in regulating Oct-2 functions. Our results indeed show that in the C-terminal domain, Ser residues 371, 389 and 394 are potential Yin Yang sites and may contribute significantly in regulating the activation of Oct-2 binding. Furthermore, alternative phosphorylation and O-GlcNAc modification at Ser191, in the N-terminal region, at Ser271 and 274 in the linker region of the two POU sub-domains and at Thr301 and Ser323 in the POUh sub-domain are likely to promote differential binding behavior of Oct-2 to the DNA octamer.

Acknowledgments

Nasir-ud-Din acknowledges partial support from HEC, Pakistan, and Pakistan Academy of Sciences for this work. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article were waived by Oxford University Press.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pabo C.O., Sauer R.T. Protein–DNA recognition. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1984;53:293–321. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.53.070184.001453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murre C., McCaw P.S., Baltimore D. A new DNA binding and dimerization motif in immunoglobulin enhancer binding, daughterless, MyoD, and myc proteins. Cell. 1989;56:777–783. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90682-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gauss P., Krassa K.B., McPheeters D.S., Nelson M.A., Gold L. Zinc (II) and the single-stranded DNA binding protein of bacteriophage T4. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:8515–8519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.23.8515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Landschultz W.H., Johnson P.F., McKnight S.L. The leucine zipper: a hypothetical structure common to a new class of DNA binding proteins. Science. 1988;240:1759–1764. doi: 10.1126/science.3289117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herr W., Sturm R.A., Clerc R.G., Corcoran L.M., Baltimore D., Sharp P.A., Ingraham H.A., Rosenfeld M.G., Finney M., Ruvkun G., Horvitz H.R. The POU domain: a large conserved region in the mammalian pit-1, Oct-1, Oct-2, and Caenorhabditis elegans unc-86 gene products. Genes Dev. 1988;2:1513–1516. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.12a.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clerc R.G., Corcoran L.M., LeBowitz J.H., Baltimore D., Sharp P.A. The B-cell-specific Oct-2 protein contains POU box- and homeo box-type domains. Genes Dev. 1988;2:1570–1581. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.12a.1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corcoran L.M., Koentgen F., Dietrich W., Veale M., Humbert P.O. All known in vivo functions of the Oct-2 transcription factor require the C-terminal protein domain. J. Immunol. 2004;172:2962–2969. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.2962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Botfield M.C., Jancso A., Weiss M.A. Biochemical characterization of the Oct-2 POU domain with implications for bipartite DNA recognition. Biochemistry. 1992;31:5841–5848. doi: 10.1021/bi00140a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sivaraja M., Botfield M.C., Mueller M., Jancso A., Weiss M.A. Solution structure of a POU-specific homeodomain: 3D-NMR studies of human B-cell transcription factor Oct-2. Biochemistry. 1994;33:9845–9855. doi: 10.1021/bi00199a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verrijezer C.P., Alkema M.J., van Weperen W.W., van Leeuwen H.C., Strating M.J., van der Vliet P.C. The DNA binding specificity of the bipartite POU domain and its subdomains. EMBO J. 1992;11:4993–5003. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pevzner V., Kraft R., Kostka S., Lipp M. Phosphorylation of Oct-2 at sites located in the POU domain induces differential down-regulation of Oct-2 DNA-binding ability. Biochem. J. 2000;347:29–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanaka M., Herr W. Differential transcriptional activation by Oct-1 and Oct-2: interdependent activation domains induce Oct-2 phosphorylation. Cell. 1990;60:375–386. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90589-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Comer F.I., Hart G.W. O-GlcNAc and the control of gene expression. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1473:161–171. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(99)00176-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wells L., Vossller K., Hart G.W. Glycosylation of nucleocytoplasmic proteins: signal transduction and O-GlcNAc. Science. 2001;291:2376–2378. doi: 10.1126/science.1058714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamemura K., Hayes B.K., Comer F.I., Hart G.W. Dynamic interplay between O-glycosylation and O-phosphorylation of nucleocytoplasmic proteins: alternative glycosylation/phosphorylation of THR-58, a known mutational hot spot of c-Myc in lymphomas, is regulated by mitogens. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:19229–19235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201729200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang X., Zhang F., Kudlow J.E. Recruitment of O-GlcNAc transferase to promoters by corepressor msin3a: coupling protein O-GlcNAcylation to transcriptional repression. Cell. 2002;110:69–80. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00810-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.La D., Sutch B., Livesay D.R. Predicting protein functional sites with phylogenetic motifs. Proteins. 2005;58:309–320. doi: 10.1002/prot.20321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nikolaidis N., Makalowska I., Chalkia D., Makalowski W., Klein J., Nei M. Origin and evolution of the chicken leukocyte receptor complex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:4057–4062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501040102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scheidereit C., Cromlish J.A., Gerster T., Kawakami K., Balmaceda C.-G., Currie R.A., Roder R.G. A human lymphoid-specific transcription factor that activates immunoglobulin genes is a homoeobox protein. Nature. 1988;336:551–557. doi: 10.1038/336551a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mueller M.M., Ruppert S., Schaffner W., Matthias P. A cloned octamer transcription factor stimulates transcription from lymphoid-specific promoters in non-B cells. Nature. 1988;336:544–551. doi: 10.1038/336544a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boeckmann B., Bairoch A., Apweiler R., Blatter M.C., Estreicher A., Gasteiger E., Martin M.J., Michoud K., O'Donovan C., Phan I., Pilbout S., Schneider M. The SWISS-PROT protein knowledgebase and its supplement TrEMBL in 2003. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:365–370. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Altschul S.F., Madden T.L., Schaffer A.A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipman D.J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson J.D., Higgins D.G., Gibson T.J. CLUSTALW: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schneider T.D., Stephens R.M. Sequence logos: a new way to display consensus sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6097–6100. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.20.6097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crooks G.E., Hon G., Chandonia J.-M., Brenner S.E. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hansen J.E., Lund O., Tolstrup N., Gooley A.A., Williams K.L., Brunak S. NetOGlyc: prediction of mucin type O-glycosylation sites based on sequence context and surface accessibility. Glycoconj J. 1998;15:115–130. doi: 10.1023/a:1006960004440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Julenius K., Mølgaard A., Gupta R., Brunak S. Prediction, conservation analysis and structural characterization of mammalian mucin-type O-glycosylation sites. Glycobiology. 2005;15:153–164. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwh151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta R., Jung E., Gooley A.A., Williams K.L., Brunak S., Hansen J. Scanning the available Dictyostelium discoideum proteome for O-linked GlcNAc glycosylation sites using neural networks. Glycobiology. 1999;9:1009–1022. doi: 10.1093/glycob/9.10.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blom N., Gammeltoft S., Brunak S. Sequence- and structure-based prediction of eukaryotic protein phosphorylation sites. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;294:1351–1362. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rumelhart D.E., Hinton G.E., Williams R.J. the PDP Research Group. Learning internal representation by error propagation. In: Rumelhart D., McClelland J., editors. Parallel Distributed Processing: Explorations in the microstructure of cognition. Vol. 1. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1996. pp. 318–362. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qian N., Sejnowski T.J. Predicting the secondary structure of globular proteins using neural network models. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;202:865–884. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90564-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matthews B.W. Comparison of the predicted and observed secondary structure of T4 phage lysozyme. Biochim. Biophy. Acta. 1975;405:442–451. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(75)90109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Attwood T. The quest to deduce protein function from sequence: the role of pattern databases. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2000;32:139–155. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(99)00106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bork P., Dansekar T., Diaz-Lazcoz Y., Eisenhaber F., Huynen M., Yuan Y. Predicting function: from genes to genome and back. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;283:707–725. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seipel K., Georgiev O., Schaffner W. Different activation domains stimulate transcription from remote (‘enhancer’) and proximal (‘promoter’) positions. EMBO J. 1992;11:4961–4968. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05603.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jackson S.P., Tjian R. O-Glycosylation of eukaryotic transcription factors: implications for mechanisms of transcriptional regulation. Cell. 1988;55:125–133. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang X., Su K., Roos M.D., Chang Q., Paterson A.J., Kudlow J.E. O-linkage of N-acetylglucosamine to Sp1 activation domain inhibits its transcriptional capability. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:6611–6616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111099998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pugh B.F., Tjian R. Transcription from a TATA-less promoter requires a multisubunit TFIID complex. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1935–1945. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.11.1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henderson A., Calame K. Transcriptional regulation during B cell development. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1998;16:163–200. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Latchman D.S. The Oct-2 transcription factor. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1996;28:1081–1083. doi: 10.1016/1357-2725(96)00050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wirth T., Priess A., Annweiler A., Zwilling S., Oeler B. Multiple Oct2 isoforms are generated by alternative splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:43–51. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lillycrop K.A., Latchman D.S. Alternative splicing of the Oct-2 transcription factor RNA is differentially regulated in neuronal cells and B cells and results in protein isoforms with opposite effects on the activity of octamer/TAATGARAT containing promoters. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:24960–24965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laumen H., Nielsen P.J., Wirth T. The BOB.1/OBF.1 co-activator is essential for octamer-dependent transcription in B cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2000;30:458–469. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200002)30:2<458::AID-IMMU458>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cepek K.L., Chasman D.I., Sharp P.A. Sequence-specific DNA binding of the B-cell-specific co-activator OCA-B. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2079–2088. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.16.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sharif M.N., Radomska H.S., Miller D.M., Eckhardt L.A. Unique function for carboxyl-terminal domain of Oct-2 in Ig-secreting cells. J. Immunol. 2001;167:4421–4429. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Christlet T.H.T., Veluraja K. Database analysis of O-glycosylation sites in proteins. Biophys. J. 2001;80:952–960. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(01)76074-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Elhammer A.P., Poorman R.A., Brown E., Maggiora L.L., Hoogerheide J.G., Kezdy F.J. The specificity of UDP-GalNAc: polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase as inferred from a database of in vivo substrates and from the in vitro glycosylation of proteins and peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:10029–10038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hansen J.E., Lund O., Engelbrecht J., Bohr H., Nielsen J.O., Hansen J.-E.S., Brunak S. Prediction of O-glycosylation of mammalian proteins: specificity patterns of UDP-GalNAc: polypeptide Nacetylgalactosaminyltransferase. Biochem. J. 1995;308:801–813. doi: 10.1042/bj3080801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kreegipuu A., Blom N., Brunak S., Järv J. Statistical analysis of protein kinase specificity determinants. FEBS Lett. 1998;430:45–50. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00503-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]