ONE of the most important tasks of general practice is to look after patients who are dying. The general practitioner (GP) is usually the one person who can provide continuity and support for patients from the start of their illness to the end, and who tries to ensure that they die without distress and, if possible, in a place of their own choosing.

We often achieve this with cancer, but find it much harder to provide a ‘good death’ for patients dying from heart failure or advanced respiratory disease. This issue of the Journal contains two papers that shed light on this important and under-researched area: one of them comes from Leicester in the United Kingdom (UK), and examines the processes of care for patients dying from cardiac and respiratory causes in two general practices;1 the other comes from Auckland, New Zealand, and explores the ways in which a range of GPs perceive themselves as discussing prognosis with patients who have severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).2

One of the most striking features of the Leicester study is the similarity between patients dying of cancer and those dying of cardiorespiratory disease. There was no significant difference in age, comorbidity, continuity of care, or the proportion who died at home. We know from other studies that the symptom burden is also similar, including depression, cachexia, fatigue, and generalised pain, in addition to the severe breathlessness that characterises advanced cardiorespiratory disease. Patients with cardiorespiratory disease, therefore, have palliative needs at least as great as those patients with cancer. This is a fact that has been known since 1963, when John Hinton published a study of patients dying in hospital, which provided a major stimulus to the growth of the hospice movement.3 But this knowledge is only now being acted on, and only in a sporadic way throughout the UK.

The study from Auckland explores one of the reasons why it has taken us so long, and why we are still so bad at providing an equal standard of care to all patients who are dying. A major barrier to helping patients with advanced COPD is our reluctance to discuss the possibility of death. In both end-stage respiratory disease and end-stage heart failure, the typical pattern of end-of-life care is a series of increasingly desperate attempts at life-prolonging intervention. This was a notable feature of the landmark SUPPORT study in the United States,4 and although the detail may not apply to every health system, repeated hospital admission is an almost invariable feature of the last year of life with COPD and heart failure. Worsening dyspnoea is a symptom that every reflex in our body tells us not to ignore: it is terrifying for the patient, distressing for the relatives who watch it for hours, and often frightening for the doctor who has no means of relieving it. So admission to hospital may be the only humane or indeed practicable option. However, all too often the patient is discharged home a few days later without a clear plan for symptom management or advice on how to prevent or manage a future emergency.

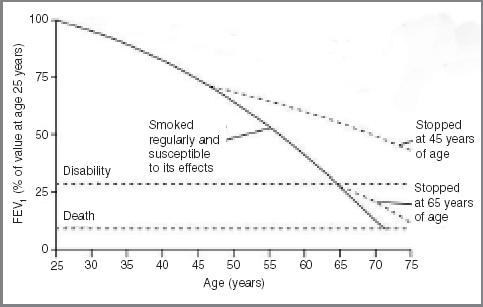

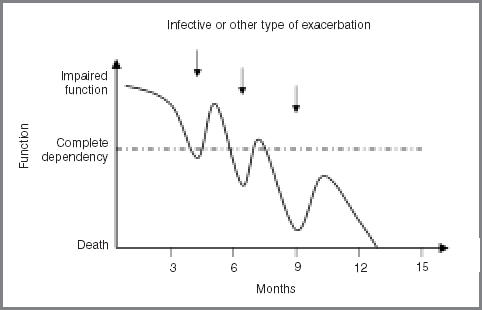

Patients and relatives become exhausted and demoralised if they feel that nothing can be done to help their overall predicament or forestall future emergencies. Infective exacerbations in COPD, and episodes of decompensation in chronic heart failure, produce a disease trajectory which, at the end stage, no longer resembles the idealised curve of the Fletcher–Peto plot5 (Figure 1), but is more a series of steep dips followed by a recovery to impaired function (Figure 2). The doctor may be little better than anyone else at predicting which dip is going to be the final one. This is particularly true of heart failure, where death occurs suddenly in roughly half of patients.6

Figure 1.

The Fletcher–Peto plot of the end-stage disease trajectory in COPD. (Reproduced with permission from the BMJ Publishing Group5)

Figure 2.

Typical end-of-life disease trajectory in COPD and chronic heart failure.

A study like the one in Auckland,2 which limited itself to interviewing doctors, can only discover what doctors think they do, or think they ought to do. Unfortunately, it does not tell us what they actually do, or how well they succeed. A previous study has shown that there is a large disparity between what GPs think they do and how they actually handle the communication issues in end-stage respiratory disease.7 A recent study of patients dying from cancer shows that it is possible to combine interviews with professionals, patients, relatives, and carers in a ‘360-degree’ analysis of what actually happened.8 This is an approach that deserves much wider adoption, even though the results may be painful to professional pride. This study revealed that it may be the doctor who is seen as evasive, unhelpful, or rushed; different doctors gave different stories, or seemed to make promises they did not deliver, whereas others (usually not doctors) were praised for sharing the pain and anxiety, and staying close to the patient.

A recent cover of The Lancet blazoned the statement:

‘COPD should not engender therapeutic nihilism, but should be approached aggressively with the recognition that optimum patient outcomes will depend in great measure on the skill of the providing physician’.9

Fortunately, the model of the ‘skilful’ physician trying ever more aggressive treatments in COPD (and heart failure) is being replaced by a model of shared decision making and supportive care in the community, and there is evidence that this really can provide ‘optimum patient outcomes’.10 In both COPD and chronic heart failure, we are gradually moving towards a model of chronic disease management in primary care, similar to the model that has already transformed the care of diabetes. The aims are to help patients to understand their condition, to ensure that it is monitored adequately, and to teach patients how, and when, to seek help. The essential foundation is structured care by GPs and practice nurses with suitable training. Specialist heart failure and respiratory nurses can then deploy their expertise effectively, by acting as educational resources, helping to support patients in difficulty, and by liaising with the hospital services. If we are to offer proper care for the end stage, it must be based on proper care of the disease process itself.

As patients approach death, support for the carers becomes at least as important as support for the patient, and symptom control becomes at least as important as treatment directed at physiological parameters such as FEV1 or the systolic ejection fraction. At this point we need to bring in the resources of palliative care, including social and psychological support from palliative care nurses, specialist advice on symptom control, and arrangements to ensure continuity of care out of hours. Relatives and carers become exhausted after months of looking after a person who is weak and breathless, who may well have become depressed and demanding. Their needs could be addressed by widening the availability of day hospices and respite admission. Finally, we can borrow ideas from cancer care, and put in place an end-of-life pathway that offers the option of dying at home.

Clearly, it is going to require time and effort before such patterns of care can become widespread in the UK. However, the building blocks are already available — a generic model for use in primary care is the Macmillan Gold Standard Framework, most of which can be applied directly to dying patients with a non-cancer diagnosis.

The impetus for improved supportive care of patients dying at home from cardiorespiratory disease is not likely to come from secondary care or, in most cases, from palliative care. The creation of local structures is a challenge that GPs with an interest can, and should, take up themselves.

References

- 1.McKinley RK, Stokes T, Exley C, Field D. Care of people dying with malignant cardiorespiratory disease in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:909–913. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halliwell J, Mulcahy P, Buetow S, et al. GP discussion of prognosis with patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:904–908. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hinton JM. The physical and mental distress of the dying. Q J Med. 1963;32:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Claessens MT, Lynn J, Zhong Z, et al. Dying with lung cancer or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: insights from SUPPORT. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(5 Suppl):S146–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fletcher C, Peto R. The natural history of chronic airflow obstruction. BMJ. 1977;1(6077):1645–1648. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6077.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poole-Wilson PA, Uretsky BF, Thygesen K, et al. Mode of death in heart failure: findings from the ATLAS trial. Heart. 2003;89(1):42–48. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.1.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fried TR, Bradley EH, O'Leary J. Prognosis communication in serious illness: perceptions of older patients, caregivers, and clinicians. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(10):1398–1403. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, et al. Patient and carer perspectives: a man with inoperable lung cancer. Progress in Palliative Care. 2003;11(6):321–326. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rennard SI. Treatment of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2004;364(9436):791–802. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16941-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blue L, Lang E, McMurray JJ, et al. Randomised controlled trial of specialist nurse intervention in heart failure. BMJ. 2001;323(7315):715–718. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7315.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]