Abstract

The interaction between enzymes of a nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) complex relies on the interplay of compatible sets of donor and acceptor communication-mediating (COM) domains. Hence, these domains are essential for the formation of a defined biosynthetic template, thereby directing the synthesis of a specific peptide product. Without the selectivity provided by different sets of COM domains, NRPSs should form random biosynthetic templates, which would ultimately lead to combinatorial peptide synthesis. This study aimed to exploit this inherent combinatorial potential of COM domains. Based on sequence alignments between COM domains, the crosstalk between different biosynthetic systems was predicted and experimentally proven. Furthermore, key residues important for maintaining (or preventing) NRPS interaction were identified. Point mutation of one of these key residues within the acceptor COM domain of TycC1 was sufficient to shift its selectivity from the cognate donor COM of TycB3 toward the noncognate donor COM domain of TycB1. Finally, an artificial NRPS complex was constructed, constituted of enzymes derived from three different biosynthetic systems. By virtue of domain fusions, the interactions between all enzymes were established by the same set of COM domains. Because of the abrogated selectivity, this universal communication system was able to simultaneously form two biosynthetic complexes that catalyzed the combinatorial synthesis of different peptide products.

Keywords: nonribosomal peptide synthetase, peptide antibiotics, protein-protein interaction

Nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) represent large enzymatic templates for the biosynthesis of a structurally diverse and pharmacologically important class of peptides (1, 2). Prominent representatives are the antibiotics daptomycin and vancomycin, the siderophore enterobactin, and the antitumor drug bleomycin. The NRP biosynthetic complexes employ a multimodular organization, with each module being responsible for the specific recognition, activation, and incorporation of one amino acid into the nascent peptide chain. Accordingly, a single module can be subdivided into individual catalytic domains, i.e., responsible for amino acid adenylation (A; A) domains and covalent thioester-binding [peptidyl-carrier-protein (PCP) domains]. In addition, the modular organization implies a strict colinearity between the biosynthetic template and primary structure of the peptide product. During the last decade, several strategies have been used to exploit this colinearity and to manipulate NRP assembly lines to generate peptides with altered biological properties. The manipulation was usually achieved by domain- or module-swapping, while the overall organization of the biosynthetic complex remained unchanged. Eventually, this manipulation should lead to the biocombinatorial synthesis of innovative peptide antibiotics (3-6). However, given the expenditure of time and labor required for genetic manipulation of biosynthetic templates, this goal was a distant prospect.

In the vast majority of known NRPS complexes, the modules are distributed over two or more NRPSs that have to selectively interact and communicate with each other to bring about the synthesis of a defined peptide product (i.e., tyrocidine (Tyc) A; Fig. 1). In our quest to decipher the molecular basis for the selective interaction between NRPSs, we recently discovered and verified the decisive role of communication-mediating (COM) domains (7). According to this study, a donor COM domain (COMD) located at the C terminus of an aminoacyl- or peptidyl-donating NRPS and an acceptor COM domain (COMA) located at the N terminus of the accepting partner NRPS form a matching (compatible) set, required for the proper intermolecular interaction between adjacent modules (i.e., TycA/TycB1 and TycB3/TycC1). In contrast, COMD and COMA domains of nonpartner NRPSs are considered non-matching (or incompatible), preventing false contact between these enzymes (i.e., TycA and TycC). By means of COM-domain-swapping experiments, it was shown, however, that an interaction between nonpartner NRPSs, and even crosstalk between different biosynthetic systems, can be enforced by providing the corresponding enzymes with matching sets of COM domains.

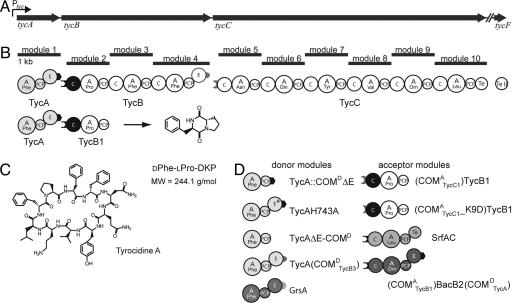

Fig. 1.

The Tyc biosynthetic system. The enzymatic assembly line of Tyc (C) consists of three NRPSs: TycA, TycB, and TycC, which are encoded by the polycistronic genes ty-cABC (A). The NRPSs are composed of one, three, and six modules, respectively, each one responsible for the incorporation of one monomeric amino acid (B). Selective interaction between partner enzymes is mediated by two compatible sets of COM domains, located at the termini of the corresponding enzymes. (D) Domain organization of donor and acceptor modules used in this study.

Thus, the intermolecular communication between partner NRPSs relies on the interplay of compatible sets of COM domains. Consequently, these domains are essential for the formation of a defined biosynthetic template and synthesis of a specific peptide product. Without the selectivity provided by different sets of compatible COM domains, the enzymes of an NRPS complex could form random biosynthetic templates that would synthesize a vast array of different peptide products, tantamount to combinatorial synthesis, which represented the ultimate goal of all engineering efforts attempted so far.

Our study aimed to exploit this inherent potential of COM domains to establish a universal communication system (UCS) for the biocombinatorial synthesis of nonribosomal peptides. To this end, a more comprehensive knowledge about the generality, selectivity, and portability of COM domains was required.

Results

Generality of COM Domains; Crosstalk Between NRP-Biosynthetic Systems. As shown recently, compatible pairs of COM domains can be used to enforce communication between nonpartner enzymes [i.e., TycA/(COMATycB1)TycC1 and TycB3(COMDTycA)/TycB1] and even crosstalk between different NRP biosynthetic systems [TycA/SrfAC and TycB3(COMDTycA)/SrfAC] (Fig. 1D). To verify the general appearance of COM domains in bacterial NRPS systems, sequence comparisons of putative COMD and COMA domains derived from 12 biosynthetic systems were carried out (Fig. 2). This analysis confirmed the existence of the conserved sequence motifs “TPSD” and “LQEGMLFH” at the proposed transition points between epimerization (E) and COMD domains, and between COMA and condensation (C) domains, respectively. Furthermore, this analysis revealed that the COM domains of TycB1 and SrfAC, COMATycB1 and COMASrfAC, share significant sequence identity of 82%. This extensive homology is sufficient to permit crosstalk between the two biosynthetic systems (7) or, more precisely, their compatible pairs of COM domains COMDTycA/COMATycB1 and COMDSrfAB3/COMASrfAC.

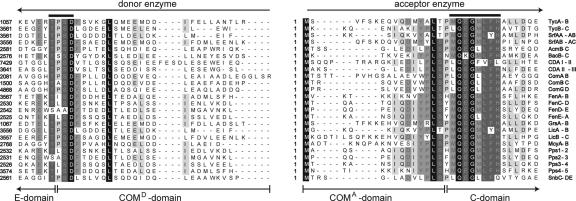

Fig. 2.

Sequence comparison of proposed COMD and COMA domains derived from 12 biosynthetic systems: actinomycin (Acm), bacitracin (Bac), complestatin (Com), calcium-dependent antibiotic (CDA), fengycin (Fen), Grs, lichenysin (Lic), microcystin (Mcy), pliplastatin (Pps), pristinamycin (Snb), SrfA, and Tyc. Invariant residues are shown in black and conserved residues in gray.

According to the same comparison, the compatible pair COM-DGrsA/COMAGrsB1, derived from the gramidicin S (Grs) biosynthetic system, also share extensive sequence identity (≈75%) with the aforementioned sets of COM domains, suggesting that, among all three sets, both COMD and COMA should be rendered interchangeable. In other words, the sequence comparison implies a possible crosstalk between the Grs and Tyc and the Grs and SrfA biosynthetic systems. A crosstalk between the Grs and Tyc had already been recognized and exploited (8) but was attributed, at that time, to the similarity of the reactions catalyzed between the two systems.

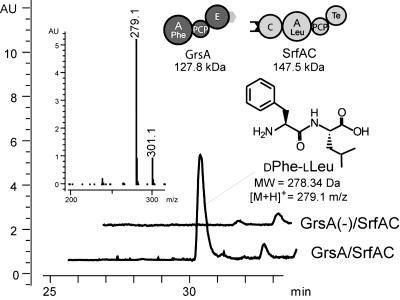

To test the hypothesis that crosstalk between different biosynthetic systems can be predicted based on the sequence identity shared by their COM domains, we investigated the productive interaction between GrsA (A-PCP-E-COMDGrsA) and SrfAC (COMASrfAC-C-A-PCP-thioesterase). Both enzymes were produced as recombinant hexahistidine-tag fusion proteins in the heterologous host Escherichia coli. After biochemical verification of their basal catalytic activities (data not shown), product-formation assays were performed and analyzed by HPLC/MS (Fig. 3). Detection of the expected dipeptide product DPhe-LLeu ([M+H]+ = 279.1 m/z) demonstrated the crosstalk between the Grs and SrfA biosynthetic systems (kobs = 0.43 min-1), thereby substantiating the generality of NRPS COM domains and the possibility of predicting productive intermolecular communication between NRPSs.

Fig. 3.

Crosstalk between Grs and SrfA biosynthetic systems. The crosstalk between GrsA and SrfAC was postulated based on the observed sequence homology (see Fig. 2) of their COM domains. HPLC/MS verified formation of the expected DPhe-LLeu dipeptide product (retention time, 30.8 min; [M+H]+ = 279.1 m/z) in the presence of DPhe and LLeu substrates.

Selectivity of COM Domains; Determination of Selectivity-Conferring Residues. Crosstalk experiments verified that members of the compatible pairs COMDTycA/COMATycB1, COMDSrfAB3/COMASrfAC, and COMAGrsA/COMDGrsB1 are rendered interchangeable. Among other things, this means that COMDTycA is able to readily interact not only with its cognate partner COMATycB1 but also with the miscognates COMASrfAC and COMAGrsB1. COMDTycA does not, however, form a productive complex with the noncognate COMATycC1, although they are derived from the same biosynthetic system. These facts, along with the observation that cognate and miscognate, but not the noncognate, COM domains share a significant amount of amino acid similarity, implied that only certain key residues, rather than all 15-25 constituting amino acid-residues, may be responsible for facilitating interaction between partner NRPSs and/or repulsion of nonpartner enzymes.

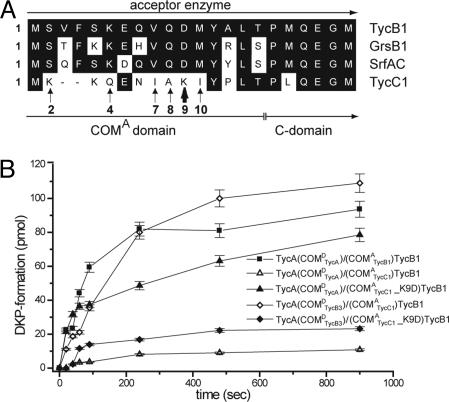

To determine putative selectivity-conferring residues decisive for rendering a COMA domain into a compatible or noncompatible partner of COMDTycA, a sequence comparison was carried out (Fig. 4A). This analysis revealed that the noncognate COMATycC1 primarily differs in the following six positions from COMATycB1, COMASrfAC, and COMAGrsB1 (numbering refers to the primary sequence of TycC1): K2S, Q4K, I7V, A8Q, K9D, and I10M. The observed amino acid substitutions can be categorized into four groups: (i) conservative exchanges between hydrophobic amino acids (I7V and I10M), (ii) substitution of a hydrophobic against a polar residue (A8Q), (iii) exchange of a polar against a basic moiety (K2S and Q4K), and (iv) substitution of a basic against an acidic moiety (K9D). Because the latter substitution certainly represented the most significant difference between cognate/miscognate and noncognate COMA domains, its relevance was analyzed on the basis of site-directed mutagenesis.

Fig. 4.

Effect of K9D point mutation in COMATycC1. (A) Sequence comparison revealed the potential importance of the COMATycC1 residue Lys-9 for preventing the unspecific interaction with the noncognate COMDTycA. (B) DKP-formation assays confirmed this hypothesis, showing that the point mutant (COMATycC1_K9D)TycB1 essentially lost its ability to interact with TycA(COMDTycB3). At the same time, the mutant gained the ability to form a productive complex with TycA(COMDTycA).

As model systems, we chose the wild-type system TycA-(COMDTycA)/(COMATycB1)TycB1, synthesizing the enzyme-bound dipeptide DPhe-LPro-S-Ppant, which is autocatalytically released under formation of the cyclic product DPhe-LPro diketopiperazine (DKP, Fig. 1B). By means of COM-domain-swapping, it was shown earlier that only enzymes equipped with compatible pairs of COM domains, COMDTycA/COMATycB1 (wild type) and COMDTycB3/COMATycC1, were able to promote DKP formation, whereas the noncompatible sets COMDTycA/COMATycC1 and COMDTycB3/COMATycB1 failed to do so (7). In this study, we constructed the (COMATycC1)TycB1 point mutant (COMATycC1_K9D)TycB1 and established its basic catalytic activities (data not shown).

Subsequently, the mutant's ability or inability to promote productive complex formation with the donor enzymes TycA-(COMDTycA) and TycA(COMDTycB3) was investigated (Fig. 4B). This analysis revealed that the K9D mutation largely compromised the COMA domain's ability to form a productive complex with its native partner COMDTycB3 (loss-of-function). At the same time, however, the point mutation facilitated the enzyme (COMATycC1_K9D)TycB1 with the ability to interact with the originally noncognate donor enzyme TycA(COMDTycA) (gain-of-function), thereby substantiating the lysine residue's critical role for the establishment of protein-protein communication. When compared to the native system TycA(COMDTycA)/(COMATycB1)TycB1 (kobs = 0.62 min-1), the product-formation rate was only slightly impaired (kobs(COMDTycA/COMATycC1_K9D) = 0.38 min-1). In contrast, analysis of the system TycA(COMDTycB3)/(COMATycC1_K9D)TycB1 revealed only residual activity (kobs-(COMDTycB3/COMATycC1_K9D) = 0.11 min-1). These results were further corroborated by HPLC/MS analysis (data not shown).

Portability of COM Domains; Construction and Characterization of TycA Derivatives. Another important issue with regard to the possible exploitation of the combinatorial potential of COM domains was a broadened knowledge about their portability. In fact, activity of NRPS catalytic domains may very well rely on the presence of appropriate partner domains. For example, the acyl-S-Ppant substrate of an E domain has to be presented by an designed PCP, whose primary structure is clearly distinct from a “regular” PCP, which interacts only with A and C domains (8). The same could also be true for the physical linkage between E and COMD domains, especially because it has been recognized that (i) the C-terminal half (E-COMDTycA) of TycA (A-T-E-COMDTycA) acts as an architectural bridge toward TycB1 (10), and (ii) the TycA main body (A-T-E) might contribute to the productive interaction between both partner enzymes (7).

To investigate the dependence of COMDTycA activity on a certain structural environment or domain organization, a set of TycA mutants was constructed and investigated for the ability to productively interact with the partner module TycB1. Namely (i) the E domain mutant TycAH743A, lacking epimerization activity because of an active-site His-to-Ala mutation, (ii) the deletion mutant TycAΔE-COMD, lacking the entire C-terminal half (E-COMD) of TycA, and (iii) the deletion mutant TycA::COMDΔE, lacking just the E domain but containing COMD directly fused to the enzyme's PCP. The TycA derivatives were heterologously produced in E. coli and purified to apparent homogeneity by Ni2+-affinity chromatography (data not shown). Subsequently, all constructs were subjected to LPhe-dependent ATP-pyrophosphate exchange reactions and thioester-formation assays, which assess the activity of unmutated catalytic domains (A and PCP domains). These tests revealed that all derivatives maintained full activity for substrate activation when compared to the wild-type enzyme (data not shown).

To quantitatively determine the consequences of the TycA mutations on the interaction with partner module TycB1, DKP-product-formation assays were carried out. TycA and its derivatives were preincubated with ATP and phenylalanine (D- and LPhe, respectively), to facilitate formation of the Phe-S-Ppant enzyme. Subsequently, the reaction mixtures were combined with the pre-loaded acceptor module L[14C]Pro-S-Ppant TycB1. DKP-product formation was monitored after organic extraction by the accumulation of the radiolabeled DPhe-[14C]LPro DKP product in the organic layer. As shown in Table 1, only TycA derivatives carrying COMDTycA were able to facilitate the formation of DKP. In the absence of a functional E domain, product formation relied on the presence of DPhe substrate. However, DKP formation, as a measure for the productive interaction between donor and acceptor enzymes, was independent of the actual structural environment of COMDTycA. In fact, TycAH743A (A-PCP-E*-COMDTycA) and TycA::COMDΔE (A-PCP-COMDTycA) revealed similar catalytic activities when compared to the wild-type enzyme (TycA: kobs = 0.55 min-1; TycAH743A: kobs = 0.53 min-1; TycA::COMDΔE: kobs = 0.50 min-1). In contrast, TycAΔE-COMD, which actually lacks COMD, was completely inactive in the DKP-product-formation assay and gave the same pattern as the control reaction without Phe substrate.

Table 1. Rates of DKP product formation determined for bimodular systems of TycA deletion mutants and TycB1.

| TycB1

|

||

|---|---|---|

| kobs(L-Phe) | kobs(D-Phe) | |

| TycA | 0.53 min-1 | 0.55 min-1 |

| TycAH743A | n.d. | 0.50 min-1 |

| TycA::COMDΔE | n.d. | 0.48 min-1 |

| TycAΔE-COMD | n.d. | n.d. |

Portability of COMDTycA. Several TycA derivatives were constructed and analyzed for their ability to promote DKP product formation with the native partner enzyme TycB1. The table summarizes the observed product formation rates kobs independent of the donor substrate (LPhe vs. DPhe) used. n.d., none detected.

Construction of a Cloning Vector for the Establishment of a Universal Communication System (UCS). With the newly gained knowledge about COM domains, basically all tools for exploiting their biocombinatorial potential were available. The general idea was as follows.

Within a hypothetical trienzyme, trimodular NRPS system A-B-C, the flux of reaction intermediates, and, therefore, the specific formation of the tripeptide product a-b-c, is controlled by two different sets of COM domains, COMDA/COMAB and COMDB/COMAC. Given the COM domain's selectivity, the initiation module A can productively interact only with the elongation module B, yielding the formation of the enzyme-bound intermediate a-b-S-Ppant. The dipeptidyl moiety is subsequently translocated from the elongation module B to the termination module C, whose interaction is facilitated by COMDB/COMAC. Here, the tripeptide product a-b-c-S-Ppant is formed and released from the biosynthetic template. However, if the trienzyme system used the same COM domains to mediate the communication between A and B and B and C, the initiation module A should be equally able to establish stable interactions with the elongation enzyme B (final complex, A-B-C) and the termination module C (final complex, A-C) (Fig. 5A). Consequently, this degenerated system should catalyze the formation of a mixture of the dipeptide a-c, as well as the tripeptide a-b-c rather than the specific formation of just one defined product, by this means, meeting the requirements envisioned for a simple biocombinatorial NRPS system.

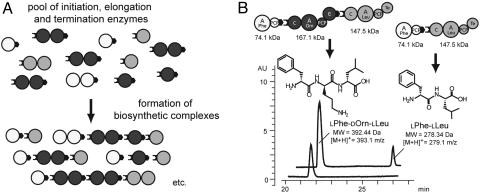

Fig. 5.

The UCS. (A) General principle of UCS. Note, all protein-protein interactions are mediated by the same set of COM domains. (B) Possible NRPS complexes formed by the initiation enzyme TycA::COMDΔE, the elongation enzyme COMATycB1-(C-AOrn-PCP-E)BacB2-COMDTycA-His, and the termination enzyme SrfAC. HPLC/MS confirmed the simultaneous formation of the expected tripeptide LPhe-DOrn-LLeu ([M+H]+ = 393.1 m/z, expected mass, 393 m/z; retention time: 21.8 min), and the dipeptide LPhe-LLeu ([M+H]+ = 279.1 m/z, expected mass: 279 m/z, retention time: 26.1 min).

To test this hypothesis, we took advantage of the cognate COM-domain pair COMDTycA/COMATycB1 and the known crosstalk between the initiation enzyme TycA and the termination enzyme SrfAC. The missing piece for the establishment of a UCS, the elongation enzyme, should feature any NRPS elongation module with an N-terminal fusion of COMATycB1 and a C-terminal fusion of COMDTycA, hereby enabling the elongation enzyme to maintain a stable interaction with the donating enzyme TycA, the accepting enzyme SrfAC, and even with itself. To ease the engineering of such an elongation enzyme, the universal communication vector pUCS03 was constructed, featuring the following characteristics: (i) pUCS03 is a derivative of pTrcHis2-TOPO (Invitrogen), facilitating the production of C-terminal hexahistidine-tag fusion proteins; (ii) the vector carries the gene fragments, encoding for COMDTycA and COMATycB1 in an inverted orientation; (iii) the coding regions of COMA and COMD are separated by a multiple cloning site containing the flanking restriction sites for XbaI and NheI; and (iv) in-frame cloning of gene fragments of NRPS modules, using the compatible restriction sites NheI and AvrII, leads to the formation of fusion genes comATycB1::nrps::comDTycA::his, under conservation of the primary sequence at the interfaces between COMA and C domain and between E and COMD domain.

Challenging and Testing the UCS; Construction of pUCS-(B1)bacB2(A). To verify functionality of the UCS, the coding fragment of the elongation module BacB2 (C-A-PCP-E), derived from the bacitracin (Bac) biosynthetic system, was cloned into pUCS03 to give pUCS-(B1)bacB2(A). This plasmid contains a fusion gene, encoding for an artificial, monomodular elongation enzyme with the domain organization COMATycB1-(C-AOrn-PCP-E)BacB2-COMDTycA-His. The NRPS was heterologously produced in E. coli and purified as described before. Subsequently, the integrity of A and PCP domains was established, verifying the enzyme's integrity and expected activity for the activation and covalent binding of the substrate LOrn (data not shown).

The UCS's biocombinatorial potential was analyzed in product-formation assays. To this end, the initiation enzyme TycA::COMDΔE, the elongation enzyme COMATycB1-(C-AOrn-PCP-E)BacB2-COMDTycA-His, and the termination enzyme SrfAC were incubated along with their cognate substrate amino acids LPhe, LOrn, and LLeu, as well as ATP. Subsequent HPLC/MS analysis clearly verified the simultaneous formation of both biosynthetic products, tripeptide LPhe-DOrn-LLeu ([M+H]+ = 393.1 m/z, expected mass, 393 m/z; retention time, 21.8 min) and dipeptide LPhe-LLeu ([M+H]+ = 279.1 m/z, expected mass, 279.1 m/z; retention time, 26.1 min) (see Fig. 5b). The formation of both products relied on the presence of the corresponding enzymes, along with their cognate substrates (data not shown), and observed rates were in the same ballpark (kobs(LPhe-LLeu) = 0.05 min-1 and kobs(LPhe-DOrn-LLeu) = 0.15 min-1) as for other systems tested (ref. 7 and this study). The timely delayed appearance of the dipeptide product can be explained by the preference of SrfAC's C domain for an incoming D-configured amino acid (10). Most notably, however, synthesis of the tripeptide product LPhe-DOrn-LLeu is the result of the, by then, unprecedented interaction of three NRPSs derived from three different NRP biosynthetic systems (Tyc, Bac, and SrfA). The communication of the different enzymes is mediated by the cognate COM domain pair COMDTycA/COMATycB1 and the miscognate pair COMDTycA/COMASrfAC, certifying herewith the biocombinatorial potential of NRPS COM domains.

Discussion

According to the molecular logic of NRP biosynthetic assembly lines, productive synthesis of a defined peptide product relies on the selectivity of amino acid-incorporating modules and the appropriate pairing of compatible catalytic domains (5, 8, 10, 12, 13). In multienzymatic NRPS complexes, which actually represent the vast majority of known NRP assembly lines, synthesis also requires the proper communication between partner enzymes and the prevention of unselective interactions between nonpartner enzymes. In the latter case, the necessary selectivity is provided by the interplay of COMD and COMA domains, located at the termini of the corresponding NRPSs (7). Without the selectivity provided by different sets of compatible COM domains, the enzymes of a NRPS complex would form random biosynthetic templates (Fig. 5A), causing the simultaneous synthesis of different peptide products. Our study aimed to investigate and abrogate the selectivity barrier provided by the COM domains to establish a UCS for the biocombinatorial synthesis of nonribosomal peptides.

By means of sequence comparisons of the intermolecular junctions between E and C domains, putative sets of COM domains were determined for 12 representative bacterial NRPS systems. The transition points between E and COMD domains and between COMA and C domains coincided with the appearance of the highly conserved sequence motives TPSD (donor site) and L(T/S)P(M/L)QEG (acceptor site), which were already determined for the Tyc biosynthetic system (7). Strikingly, some COM domains share a sequence homology of >70%. As shown here, this remarkable homology represents an indication for the possible miscognate interaction between nonpartner NRPSs and can be used as a predictive tool to forecast crosstalk between NRP biosynthetic systems.

The observation that cognate and miscognate, but not noncognate, COM domains share a significant extent of homology implied that only certain key residues, rather than all 15-25 constituting amino acids, are decisive for a COM domain's selectivity. In fact, by means of site-directed mutagenesis, we could show that a single Lys-to-Asp point mutation within COMATycC1 was sufficient to prevent it from interacting with its native partner COMDTycB3 (loss-of-function) and to render it, instead, a compatible counterpart of COMDTycA (gain-of-function).

Although the overall sequence homology between COM domains averages only ≈50%, their amino acid composition turned out to be intriguingly standard. In fact, COMD domains are characterized by a higher-than-average appearance of acidic amino acids, as reflected by their average pI of 3.3 ± 0.2 (pI of entire NRPSs, 5.2 ± 0.2). COMA domains, in contrast, contain an excess of polar amino acids and possess an average pI of 6.6 ± 0.8, suggesting that the selective communication is predominantly established by polar and/or electrostatic interactions, provided by distinct pairs of amino acid residues located at the area of contact between COMD and COMA. Point mutations within this contact surface should weaken the interaction with the cognate partner and, possibly, change the selectivity in favor of noncognate COM domains. Apparently, this is exactly what was observed in this study for the point mutant COMATycC1(K9D), which revealed low selectivity for the cognate COMDTycB3 and a newly established capability to interact with the noncognate COMDTycA.

Based on the crystal structure of the free-standing C domain VibH of the vibriobactin biosynthetic system (9) as well as secondary structure predictions, both COMD and COMA are believed to possess α-helical structures, representing another striking parallel with the functionally related docking domains of polyketide synthases, which have been likewise shown to facilitate the intermolecular communication within multienzyme polyketide synthase complexes (11). Compatible pairs of donor and acceptor docking domains (80- to 100- and 20- to 30-aa residues in length, respectively) form a four-helix bundle that is stabilized by polar and electrostatic effects. Given the shortness of the NRPS COM domain (15-2 residues), compatible pairs are rather likely to establish a leucine-zipper-like motif. This model is actually supported by the analysis of cognate/miscognate and noncognate acceptor COM domains (this study), revealing that major differences are observed approximately every three amino acid residues, therefore matching very well the known rise per repeating unit within an α-helical structure.

We propose that the area of contact between a compatible pair of COM domains is formed by five pairs of amino acid residues located on two antiparallel α-helices and with COMD and COMA both contributing one helix. In case of COMDTycA/COMATycB1, the selectivity-conferring residues are postulated as follows (core motifs in bold, key residues underlined): COMDTycA: TPSDFS5 VKGLQ10 MEEMD15 DIFEL20 LANTL25 R; COMATycB1: MSVFS-15 KEQVQ-10 DMYAL-5 TPMQE0 GMLFH. According to our current working model, K7(COMDTycA) interacts with D-9 (COMATycB1), Q10 with Q-12,E12 with K-14,E13 with S-15, and D16 with S-18, giving rise to two electrostatic and three polar interactions. Using the conserved core motifs as structural anchor, we did the same assignment for all 12 COM domain pairs of the Tyc, Grs, SrfA, lichenicin, fengycin, and Bac biosynthetic systems and found that, among the 120 presumed selectivity-conferring amino acids, >96% are actually polar or charged residues. Furthermore, among the 60 putative amino acids pairs formed between COMD and COMA,59(>98%) would allow for the establishment of productive polar or electrostatic interactions. Interestingly, the model also gives a plausible explanation for the outcome of the mutagenesis studies, because COMDTycA/COMATycB1 (K2/D-9) and COMDTycB3/COMATycC1 (D2/K-9) actually possess an inverse distribution of acidic and basic charges in this position.

A major requirement for both the engineering of artificial NRPSs and approaches for the synthesis of NRPs is the portability of catalytic domains. In the UCS TycA::COMDΔE/COMATycB1-(C-AOrn-PCP-E)BacB2-COMDTycA-His/SrfAC, COMDTycA was directly fused to a PCP, whereas COMATycB1 was attached to an internal (rather than an N-terminal) C domain. The UCS's functionality clearly demonstrated the portability of involved COM domains by the simultaneous formation of the expected di- and tripeptide products.

Most recently, Menzella et al. (14) reported on a very similar goal in the analogous polyketide synthases. By exploiting a compatible set of interpeptide linkers (also referred to as docking domains, the counterparts of NRPS COM domains), Menzella et al. investigated the productive interaction between 154 bimodular combinations of donor and acceptor modules and found that nearly half of the combinations successfully mediated the biosynthesis of the desired triketide lactones. This approach, however, (i) is limited to the investigation of bienzymatic systems, (ii) inherently leads to the formation of defined products, and (iii) appears to be largely influenced by the nature of the modules used, because natural partner modules gave up to 2,000-fold higher yields than did nonpartner enzymes.

The UCS, in contrast, demonstrated the successful formation of random (NRP) biosynthetic complexes composed of enzymes derived from three different biosynthetic systems. The simultaneous formation of different products at rates within the same order of magnitude as natural NRP biosynthetic systems verified the tremendous biocombinatorial potential of COM domains. Substantiation of the proposed model for the interaction between COMD and COMA and the exploitation and investigation of UCS as a tool for truly biocombinatorial synthesis of NRPs and, eventually, peptide antibiotics await further study.

Materials and Methods

Strains, Culture Media, and General Methods. The E. coli strains were grown in LB medium, supplemented, if applicable, with 50 μg/ml ampicillin, 25 μg/ml kanamycin, and/or 20 μg/ml chloramphenicol (final concentrations). Standard procedures were applied for all DNA manipulations (15). Oligonucleotides were purchased from MWG Biotech (Ebersberg, Germany). DNA sequencing confirmed the identity of all plasmids constructed.

Construction of Expression Plasmids. Construction of most expression plasmids used in this study was described in ref. 7. Plasmid pTrcHis-tycA::COMDΔE (domain organization A-PCP-COMDTycA) is a derivative of pTrcHis-TycA and was obtained by inverse PCR using the oligonucleotides (restriction sites underlined) 5′-tycA::COMDΔE(5′-AAA AGA TCT GAG CGA ACG CCC AGC G-3′) and 3′-tycA::COMDΔE (5′-TTT AGA TCT GCT CTT GAC AAA AAG AGC AAC C-3′). After digestion with BglII, the plasmid was intramolecularly religated to give pTrcHis-tycA::COMDΔE.

Constructs pTrcHis-tycAH743A and pTrcHis2-(C1K9D)tycB1 are derivatives of pTrcHis-TycA and pTrcHis2-(C1)tycB1, respectively. The mutations were introduced by using the oligonucleotides 5′-tycAH743A_for (5′-TCA TTT GTT TCT CGC AAT TCA TGC ATT GGT CGT GGA TGG CAT TTC C-3′) and 3′-tycAH743A_rev (5′-GGA AAT GCC ATC CAC GAC CAA TGC ATG AAT TGC GAG AAA CAA ATG A-3′) and 5′-(C1K9D)tycB1_for (5′-AGG AAA ACA TCG CAG ATA TTT ACC CGC TAA CCC CAT TGC-3′) and 3′-(C1K9D)tycB1_rev (5′-GGT TAG CGG GTA AAT ATC TGC GAT GTT TTC CTG CTT TTC C-3′).

Construction of Universal Communication Vector pUCS03 and Derivative pUCS-(B1)bacB2(A). The gene fragments f1 and f2, encoding for COMATycB1 and COMDTycA, respectively, were PCR-amplified from chromosomal DNA of Bacillus brevis (American Type Culture Collection 8185) by using the oligonucleotides 5′-f1_COM(B1) (5′-AAA CTG CAG CCG GAA GAG ACC GAG-3′) and 3′-f1_COM(B1) (5′-ATC TCT AGA GTG CTC TTG ATC GAG C-3′) and 5′-f2_COM(A) (5′-ATC GCT AGC GAT TTC AGC GTC AAA GG-3′) and 3′-f2_COM(A) (5′-AAA GTC GAC TGG CGA TGG TCC-3′). After purification, fragment f1 was digested with PstI and XbaI and ligated into the PstI and XbaI sites of pSU18 to give pUCS01. Subsequently, fragment f2 was digested with NheI and AccI and ligated in the NheI and AccI sites of pUCS01 to give pUCS02. pUCS02 carries the gene fragments encoding for COMATycB1 and COMDTycA in a inverted orientation, separated by a 254-bp spacer region that is terminally flanked by the recognition sites of XbaI (5′ end) and NheI (3′ end). The DNA fragment, carrying the coding regions of both COM domains and the spacer, was PCR-amplified from plasmid pUCS02 by using the oligonucleotides 5′-tycB1 (5′-ATG AGT GTA TTT AGC AAA GAA CAA GTT CAG G-3′) and 3′-tycA (5′-TTA GCG CAG TGT ATT TGC AAG CAA TTC G-3′). The purified DNA fragment was cloned into the C-terminal hexahistidine-tag fusion vector pTrcHis2-TOPO (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) to give pUCS03.

The gene fragment bacB2 was amplified from chromosomal DNA of Bacillus licheniformis (American Type Culture Collection 10716) by using the oligonucleotides 5′-bacB2 (5′-AAA GCT ACT ACA ATA TGC CTT TTG CG-3′) and 3′-bacB2 (5′-AAA CCT AGG CGT TTT TTC GGT TTC ATG-3′). After digestion with NheI and AvrII, the gene fragment was ligated into the XbaI and NheI sites of pUCS03 to give the expression plasmid pUCS-(B1)bacB2(A). This plasmid contains a fusion gene, encoding for a monomodular elongation enzyme with the domain organization COMATycB1-(C-AOrn-PCP-E)BacB2-COMDTycA-His.

Production of Recombinant Enzymes. All expression plasmids were used to transform E. coli M15(pREP4). Gene expression and purification of the gene products were carried out as described in ref. 7. Fractions containing the recombinant proteins were identified by SDS/PAGE (7.5%), pooled, and dialyzed against assay buffer (50 mM Hepes, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl) supplemented with 2 mM dithioerytritol.

Enzyme Assays and Radiolabeled Substrates. Standard assays were applied for in vitro apo-to-holo conversion of NRPS PCP domains (12), amino acid-dependent ATP-pyrophosphate exchange reactions (13), radioactive thioester formation assays (8), and product-formation assays (7). [32P]pyrophosphate was purchased from PerkinElmer Life Sciences (Rodgau-Juegesheim, Germany). Radiolabeled amino acids L[14C]Phe (453 mCi/mmol) (1 Ci = 37 GBq), L[14C]Pro (253 mCi/mmol), L[3H]Leu (141 Ci/mmol), and L[14C]Orn (53 mCi/mmol) were purchased from Amersham Pharmacia Biosciences (Braunschweig, Germany).

Acknowledgments

We thank Claudia Chiocchini for providing SrfAC protein, Katrin Eppelmann for discussions and critical reading of the manuscript, and Mohamed A. Marahiel for allowing us to carry out this study at the Institute of Biochemistry. The Federal Ministry of Education and Research sponsored this work within the scope of its BioFuture program.

Author contributions: M.H. and T.S. designed research; M.H. performed research; M.H. and T.S. analyzed data; and M.H. and T.S. wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: A, adenylation; Bac, bacitracin; C, condensation; COM, communication-mediating; COMA, acceptor COM domain; COMD, donor COM domain; DKP, diketopiperazine; E, epimerization; Grs, gramidicin S; NRP, nonribosomal peptide; NRPS, NRP synthetase; PCP, peptidyl-carrier protein; SrfA, surfactin; Tyc; tyrocidine; UCS, universal communication system.

References

- 1.Finking, R. M. & Marahiel, M. A. (2004) Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 58, 453-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cane, D. E. & Walsh, C. T. (1999) Chem. Biol. 6, R319-R325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doekel, S. & Marahiel, M. A. (2000) Chem. Biol. 7, 373-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eppelmann, K., Stachelhaus, T. & Marahiel, M. A. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 9718-9726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stachelhaus, T., Schneider, A. & Marahiel, M. A. (1995) Science 269, 69-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mootz, H. D., Schwarzer, D. & Marahiel, M. A. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 5848-5853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hahn, M. & Stachelhaus, T. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 15585-15590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linne, U., Doekel, S. & Marahiel, M. A. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 15824-15834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keating, T. A., Marshall, C. G., Walsh, C. T. & Keating, A. E. (2002) Nat. Struct. Biol 7, 522-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belshaw, P. J., Walsh, C. T. & Stachelhaus, T. (1999) Science 284, 486-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Broadhurst, R. W., Nietlispach, D., Wheatcroft, M. P., Leadlay, P. F. & Weissman, K. J. (2003) Chem. Biol. 10, 723-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linne, U. & Marahiel, M. A. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 10439-10447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stachelhaus, T., Mootz, H. D., Bergendahl, V. & Marahiel, M. A. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 22773-22781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Menzella, H. G., Reid, R., Carney, J. R., Chandran, S. S., Reisinger, S. J., Patel, K. G., Hopwood, D. A. & Santi, D. V. (2005) Nat. Biotechnol. 23, 1171-1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sambrook, J., Fritsch, E. F. & Maniatis, T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual (Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY).