Antagonists of mGluR7 may be useful in conditions involving chronic stress.

Gprotein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are the most successful class of drug targets to date (1). Almost half of the 500 molecular targets for currently used therapeutic agents are cell surface receptors, and the majority of these belong to the GPCR superfamilies. Of the GPCRs, one of the most important classes in the central nervous system is the metabotropic glutamate receptor family (mGluRs) (see ref. 2 for review). Glutamate is the neurotransmitter at the vast majority of excitatory synapses in the brain, and mGluRs provide a mechanism by which glutamate can modulate or fine tune activity at the same synapses at which it elicits fast synaptic responses through activation of ligand-gated cation channels. Because of the ubiquitous distribution of glutamatergic synapses, mGluRs participate in a wide variety of functions of the CNS (3). However, developing highly selective agonists for specific mGluR subtypes has been exceedingly difficult, likely because of the high conservation of the glutamate-binding site across members of this receptor family and the restricted structural requirements for pharmacophores that occupy this binding pocket. In a recent issue of PNAS, Mitsukawa et al. (4) report an exciting advance in the field by identifying the first highly selective agonist for an mGluR subtype termed mGluR7, a receptor that has long been postulated to be among the most important members of this family in regulating CNS function.

mGluR7 Gets a Hit

The compound described by Mitsukawa et al. (4), called AMN082, was identified by using a random high-throughput screen (HTS) of a library of small drug-like molecules in search of novel compounds that activate this receptor. From this screen and subsequent experiments, AMN082 emerged as a highly selective and potent agonist of mGluR7. In addition to providing the first selective ligand for this important receptor subtype, AMN082 acts by a unique mechanism of action, fully activating mGluR7 through an allosteric site far removed from the glutamate-binding pocket. The compound is structurally unrelated to any known mGluR ligand and provides an excellent example of the power of HTS in identifying novel compounds that are unrelated to known chemical scaffolds. Remarkably, this primary HTS hit was found to be orally active and to penetrate the blood–brain barrier. This provided a tool to directly test the hypothesis that activation of mGluR7 would increase levels of the plasma stress hormones corticosterone and ACTH, an experiment that would substantiate previous genetic studies by these authors showing that mGluR7 is an important modulator of the stress response in vivo (5). Indeed, AMN082 induced a robust increase in stress hormone levels that was absent in mGluR7 knockout animals, providing powerful support to a growing set of findings that suggest that antagonists of this receptor may be useful in conditions involving chronic stress such as depression and anxiety disorders. However, the implications of these studies go far beyond the role of mGluR7 in stress responses. This pharmacological tool provides a break-through that may ultimately impact our understanding of the basic mechanisms of glutamatergic synaptic transmission as well as aid in the expanding appreciation of possible approaches to generating compounds for the multitude of GPCRs that have been retractable to the development of highly selective orthosteric ligands.

The target of AMN082, mGluR7, is a member of a larger family of eight mGluR subtypes that have been identified in the mammalian central nervous system (see ref. 2 for review). Members of this receptor family have diverse physiological roles in virtually all major circuits of the brain. Because of the rich variety of mGluR subtypes and the broad range of activities of these receptors, the opportunity exists for developing therapeutic agents that selectively interact with mGluRs involved in only one or a limited number of CNS functions. Such drugs could have a dramatic impact on development of novel treatment strategies for a variety of psychiatric and neurological disorders.

Interestingly, mGluR7 has long been postulated to be one of the most important mGluR subtypes in regulating CNS function. As with several other members of the mGluR family, mGluR7 is primarily localized on presynaptic terminals (6, 7) where it is thought to regulate neurotransmitter release. Of the presynaptic mGluR subtypes, however, mGluR7 is the most widely distributed and is present at a broad range of synapses that are postulated to be critical for both normal CNS function and a range of human disorders. Furthermore, unlike some presynaptic mGluR subtypes, mGluR7 is localized directly in the presynaptic zone of the synaptic cleft of glutamatergic synapses (7, 8), where it is thought to act as a traditional autoreceptor that is activated by the glutamate released from the presynaptic terminal during action potentials. Based on our relatively rudimentary understanding of mGluR7, this receptor has been thought to be a key player in shaping synaptic responses at glutamatergic synapses as well as in regulating key aspects of inhibitory GABAergic transmission (7, 8). However, mGluR7 has been the most intractable of the mGluR subtypes in terms of discovery of selective ligands. Until the discovery of AMN082, there have been no selective agonists or antagonists of this receptor. Available agonists, such as l-AP4, activate mGluR7 only at concentrations 2–3 orders of magnitude higher than the concentrations required to activate its closest relatives, mGluRs 4, 6, and 8. Because of this, it has been impossible to study the physiological effects of activation of this receptor without confounding effects induced by activation of these related mGluR subtypes. Despite this lack of pharmacological tools, anatomical and cellular studies as well as experiments with mGluR7 KO mice have led to suggestions that selective ligands for this receptor have potential for treatment of a wide variety of neurological and psychiatric disorders, including depression, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, epilepsy, Alzheimer's disease, and Parkinson's disease, among others. Discovery of the first selective agonist of mGluR7 provides an exciting opportunity to begin to systematically investigate the physiological roles of this receptor and to directly test hypotheses that have arisen from these previous cellular and genetic studies.

AMN082 Acts by an Allosteric Mechanism

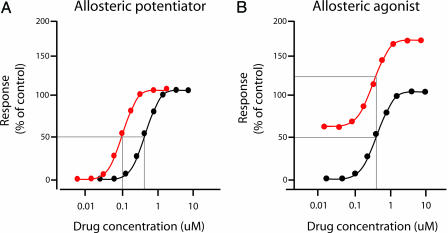

The discovery of a ligand that interacts at an allosteric site rather than the traditional glutamate binding site also represents a major advance for the study of mGluR7 and has yielded insights that are important in the broader arena of GPCR drug discovery. Recent studies with ligands at allosteric sites of other mGluR subtypes suggest that compounds can be developed that exhibit a range of activities from allosteric antagonists to neutral ligands to allosteric potentiators (9, 10). Allosteric potentiators are particularly unique in that they have no effect on their own but enhance the activity of endogenous ligand (reviewed in ref. 11) (Fig. 1). Advantages of allosteric compounds are that they often provide greater subtype selectivity, allow different pharmacophores than orthosteric ligands, and provide novel mechanisms of action for modulation of receptor function. It is possible that discovery of AMN082 will provide a scaffold from which selective antagonists or potentiators of mGluR7 activity can be developed, expanding the repertoire of tools and potential therapeutic agents targeting this receptor.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of concentration-response curves for allosteric potentiation (A) versus allosteric agonism (B). In A, a constant amount of allosteric potentiator (red curve) or vehicle (black curve) is added in the presence of increasing amounts of an orthosteric agonist. Although the potentiator has no effect on its own, it shifts the overall concentration-response curve to the left, resulting in an increase in orthosteric agonist potency as depicted by the intersection of the descending lines with the x axis. In B,a constant amount of an allosteric agonist such as AMN082 (red curve) or vehicle (black curve) is added in a similar experimental design; in this case, the entire curve is shifted up with no change in orthosteric agonist potency.

AMN082 is unique in that it is the first full agonist of an mGluR acting at an allosteric site. This mechanism of action is similar to a recently discovered agonist of the M1 muscarinic receptor, termed AC42, which acts at a site distinct from the orthosteric acetylcholine site to fully activate this receptor (12). However, the effect of AC42 is blocked by atropine, an orthosteric antagonist at M1, whereas the effect of AMN082 is not blocked by orthosteric antagonists of mGluR7. Interestingly, the mGluR5 allosteric potentiator CDPPB has been shown to partially activate mGluR5 on its own (13) and, similar to results observed with AMN082, this agonist effect is not blocked by orthosteric mGluR5 antagonists. Mitsukawa et al. report that, in new mGluR7 cell lines generated for a subset of the described studies, the effects of AMN082 appear to be more than additive with orthosteric agonists, suggesting that there may be a synergistic interaction between the two types of compounds under certain experimental conditions. Thus, it is possible that AMN082 will be found to share some mechanistic action that is related to the actions of allosteric potentiators of mGluRs and other GPCRs.

AMN082 represents an important compound on several levels; it aids in advancing the understanding of the basic molecular pharmacology of GPCR-allosteric site ligand interaction, it represents an example of the utility of high throughput screening approaches in the discovery of new ligands with novel mechanisms of action, and, lastly, it provides a much-needed pharmacological agent to begin unraveling the role of mGluR7 function in glutamatergic transmission in the CNS.

Author contributions: P.J.C. and C.M.N. analyzed data and wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

See companion article on page 18712 of issue 51 in volume 102.

References

- 1.Fang, Y., Lahiri, J. & Picard, L. (2003) Drug Discov. Today 8, 755-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schoepp, D. D. (2001) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 299, 12-20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watkins, J. C. (2000) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 28, 297-309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitsukawa, K., Yamamoto, R., Ofner, S., Nozulak, J., Pescott, O., Lukic, S., Stoehr, N., Mombereau, C., Kuhn, R., McAllister, K. H., et al. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 18712-18717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitsukawa, K., Mombereau, C., Lotscher, E., Uzunov, D. P., van der Putten, H., Flor, P. J. & Cryan, J. F. (2005) Neuropsychopharmacology, Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Ohishi, H., Nomura, S., Ding, Y. Q., Shigemoto, R., Wada, E., Kinoshita, A., Li, J. L., Neki, A., Nakanishi, S. & Mizuno, N. (1995) Neurosci. Lett. 202, 85-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kinoshita, A., Shigemoto, R., Ohishi, H., van der Putten, H. & Mizuno, N. (1998) J. Comp. Neurol. 393, 332-352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kosinski, C. M., Risso Bradley, S., Conn, P. J., Levey, A. I., Landwehrmeyer, G. B., Penney, J. B., Jr., Young, A. B. & Standaert, D. G. (1999) J. Comp. Neurol. 415, 266-284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Brien, J. A., Lemaire, W., Chen, T. B., Chang, R. S., Jacobson, M. A., Ha, S. N., Lindsley, C. W., Schaffhauser, H. J., Sur, C., Pettibone, D. J., et al. (2003) Mol. Pharmacol. 64, 731-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodriguez, A. L., Nong, Y., Sekaran, N. K., Alagille, D., Tamagnan, G. D. & Conn, P. J. (2005) Mol. Pharmacol. 68, 1793-1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen, A. A. & Spalding, T. A. (2004) Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 21, 407-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spalding, T. A., Trotter, C., Skjaerbaek, N., Messier, T. L., Currier, E. A., Burstein, E. S., Li, D., Hacksell, U. & Brann, M. R. (2002) Mol. Pharmacol. 61, 1297-1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kinney, G. G., O'Brien, J. A., Lemaire, W., Burno, M., Bickel, D. J., Clements, M. K., Chen, T. B., Wisnoski, D. D., Lindsley, C. W., Tiller, P. R., et al. (2005) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 313, 199-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]